Keeping Up With Changes in Rheumatoid Arthritis Management

Overview of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

RA is, by far, the most common systemic inflammatory condition seen in medical

practice and pharmacists, in a variety of practice settings, will commonly interface with

patients with this chronic arthritide. RA is characterized by symmetrical bilateral joint

involvement and articular destruction with a host of potential extraarticular

manifestations including rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis, ophthalmologic inflammation

(episcleritis), and neurologic and/or cardiopulmonary disease.1 In addition,

lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, or renal involvement

can occur.1 The opportunity for pharmacists to provide education regarding

nonpharmacological and pharmacological therapies for patients with RA is immense

and presents an excellent chance to substantially impact the care of patients with this

chronic and, as yet, incurable condition.

Etiology

Pannus, the inflamed, proliferative joint synovium characteristic of RA eventually

invades and destroys the soft and bony tissues of articular joints. (See Figure 1) Unfortunately, RA is associated with the malfunction of both the humoral and cell-mediated functions of the immune system, both of which contribute to the

pathophysiology of RA. It is well realized that rheumatoid factor (RF) and antibodies

derived from B lymphocytes (plasma cells) are commonly present in patients with RA,

with seropositive patients tending to experience more severe and more aggressive

disease.2 In patients with RA, the complement (C) system exacerbates and potentiates the dysfunctional immune response and encourages chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and

lymphokine release. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 are also

involved in the proinflammatory process. In addition T and B lymphocytes and

macrophages all contribute to produce a variety of cytotoxic substances that are

detrimental to joints and associated soft tissues.2 Histamine release and prostaglandin

production also contribute to the inflammatory process by increasing the permeability of

blood vessels.2 Together these substances contribute to edema, warmth, and the

erythema and pain associated with RA. The end result of these aforementioned

processes lead to a variety of joint pathology, which may include loss of joint space as a

result of cartilage degradation, bony fusion known as ankylosis, laxity of tendon

structures, leading to subluxation and joint instability, and/or tendon contracture,

contributing to joint deformity.1

Epidemiology

RA is estimated to affect approximately 1% to 2% of the United States population,

affecting 3 times as many women as men (between the ages of 15 and 45 years, RA

affects 6 times as many women as men) and can occur at any age, with an increasing

prevalence up to the 7th decade of life. As yet unproven, genetic predisposition may be

a factor in disease development, as well as exposure to a yet-to-be identified

environmental substance may trigger disease expression.1

An underappreciated aspect of RA is that roughly 50% of patients leave the work

force within 10 years of diagnosis and the costs incurred by patients rival those of

coronary artery disease or stroke.3

Risk Factors

Specific risk factors for RA are elusive and the precise cause is unknown. Unknown

environmental contributors, for example viral infections, are thought to play a role.4 In

addition, a birth weight greater than 4.54 kg elevates one’s risk of developing RA.4 Major histocompatibility complex molecules located on T lymphocytes appear to play an

important role in disease predisposition. In fact, patients with human lymphocyte antigen

(HLA) DR4 are 3.5 times more likely to develop RA than patients with other HLA antigens.4 Interestingly enough, high coffee consumption, particularly decaffeinated

coffee, has been proposed to contribute to RA risk, while high vitamin D intake, tea

consumption, and oral contraceptive use have been associated with decreased risk.5,6,7

Diagnosis: Signs and Symptoms of Early Diagnosis

Common clinical presentation is of a patient with self-described joint discomfort and

stiffness more than 6 weeks in duration, who may also complain of fatigue, weakness,

low-grade fever, and lack or loss of appetite. Wrists, hands, ankles, and feet are often

initially affected with joint pain, often described as joint tenderness, which is also

accompanied by warmth and swelling. Bilateral symmetrical joint involvement is

common and rheumatoid nodules may be evident in early disease. Rheumatoid nodules

occur in as many as 20% to 30% of patients with RA and most commonly occur on

extensor surfaces of the elbows, forearms, and hands; nodules can also occur in the

lungs and pleura and, in general, are asymptomatic and do not require treatment.

Virtually any articular joint can be affected and, with longer disease duration, shoulders,

elbows, knees, hips, and even the jaw or neck can become diseased.8 Joint deformity is

not always evident initially, however the patient may report muscle pain and pronounced

afternoon fatigue.

In addition to the common and early signs and symptoms previously discussed,

laboratory assessment of patients with RA include positive rheumatoid factor (present in

60% to 70% of patients) and the presence of anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP)

antibodies, along with elevations in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), both of which are nonspecific markers of inflammation.1 Furthermore, normocytic-normochromic anemia and thrombocytosis may be present.1

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of RA includes a host of conditions, and patients should

always be directed to a rheumatologist for an extensive workup and evaluation. The

differential diagnosis includes, but is not limited to, connective tissue disease,

sarcoidosis, fibromyalgia, psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, crystal-induced arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and ankylosing spondylitis.9 There are a multitude

of conditions that may present with a positive RF.9 In addition to RA, patients afflicted

with Sjögrens syndrome, SLE, progressive systemic sclerosis, or polymyositis may be

RF positive. A host of infectious diseases, such bacterial endocarditis, syphilis,

mononucleosis, and infectious hepatitis and leprosy may be associated with a positive

RF.9 Sarcoidosis, aging, cirrhosis of the liver, and chronic active hepatitis may also be

associated with a positive RF.

Benefits of Early, Aggressive Therapy

RA may take a variable and oftentimes an unpredictable course; however the

majority of patients experience a persistent, albeit sometimes fluctuating, course that is

accompanied by a progressive degree of functional impairment brought on by pain and

structural joint abnormalities. Degree of eventual disability is often correlated with the

number and degree of joints affected, extensive ESR elevations, and high titers of RF,

as well as the early evidence of bone erosions and the presence of rheumatoid nodules.

Very early in the disease course, however, it is often challenging to predict which patient

will progress to severe disability and which patient will stabilize.

The basic principles and goals of treating RA are as follows: 1) to relieve pain; 2) to

control and reduce inflammation; 3) to protect against joint destruction; 4) to control

systemic involvement; and, 5) to maintain or improve function and quality of life. The

general approach to treating a newly diagnosed patient has undergone a dramatic

transformation during the past few years. Previously it was recommended to treat with a

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) first and then progress to disease-modifying agents later in the disease course. Today, a disease-modifying antirheumatic

drug (DMARD) is recommended as first-line therapy, while NSAIDs and/or

corticosteroids can be coadministered but are no longer considered appropriate as

initial monotherapy. This is because it is now recognized that a substantial amount of

the overall joint damage occurs early in the disease rather than later, as originally

thought. While corticosteroids and NSAIDs play a crucial role in providing analgesia and

treating inflammation, they do not prevent joint damage or slow disease progression

and also have potentially debilitating long-term side effects. In one study by Fuchs and colleagues, 80% of RA patients had joint space narrowing of the hands and wrists within

2 years, while 66% had boney erosions during that same time.10 Early, aggressive

treatment has now become the gold standard and is advocated to quell ongoing

inflammation and prevent, or at least delay, joint injury.11 Therefore, every patient with

established disease should be treated with a DMARD as early as possible.

Another treatment approach recently adopted by some rheumatologists is to initiate

treatment with combination DMARD therapy.12,13 Patients started on 2 or 3 DMARDs at

the time of diagnosis are more likely to attain remission and maintain optimal functional

and clinical outcomes, when compared with patients initially treated with one DMARD.

Early aggressive therapy varies by definition, but generally refers to the treatment

of patients with methotrexate (MTX) or a biologic DMARD agent, also known as biologic

response modifiers (BRMs), early in the disease course. Certainly as DMARDs or

BRMs are introduced, coadministration with an NSAID may be appropriate and, in some

instances, the concurrent use of a corticosteroid is advantageous initially, however long-term use of corticosteroids may have significant side effects.

Factors associated with poor outcomes may be useful for identifying early RA

patients who have a greater likelihood of disease progression. These include a positive

RF test, the presence of anti-CCP antibodies, early radiographic evidence of boney

erosive disease, impaired functional status, and persistently active synovitis with high

levels of disease activity.14 These patients may be considered appropriate candidates

for the use of biologic DMARDs/BRMs at the time of diagnosis.

A 2007 analysis of pooled data from several early RA trials using combination

therapy (traditional DMARDs plus BRMs) revealed that the level of disease activity at

baseline and during the first 3 months correlated meaningfully with the level of disease

activity at 1 year.15 The authors concluded that early RA patients who have not

achieved lowered disease activity within the initial few months of standard DMARD

therapy may be candidates for BRMs.

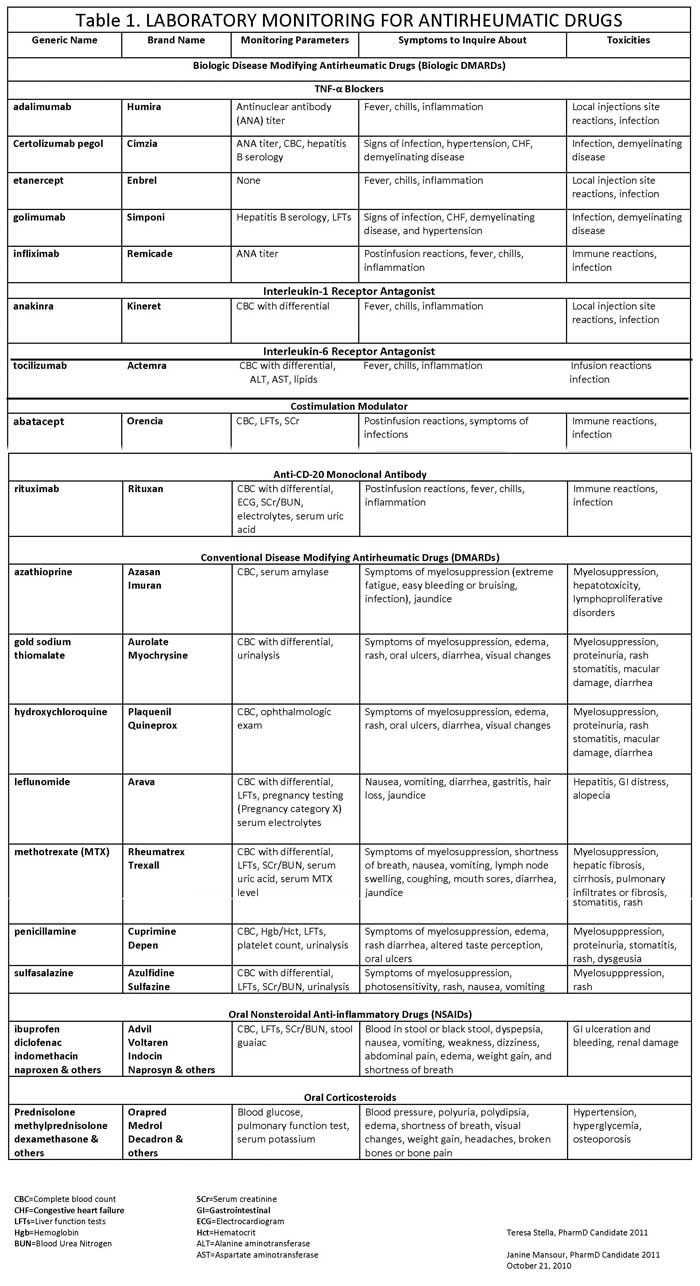

All patients receiving DMARDs should be monitored at regular intervals to evaluate

the efficacy of treatment, using standard measures of disease advocated by

organizations such as the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).16 (See Table 1)

Gaps in RA Patient Care

Education: Clinician and Patients

Rheumatologists and pharmacists have much work to do in the area of educating

both non-rheumatological medical colleagues and patients regarding the devastating

consequences of RA. Undertreatment and misunderstanding of the disease course can

have a dramatically negative impact on patients’ lives. Therefore, both clinicians treating

RA and patients with this diagnosis need to be persistently and effectively educated. In

addition to understanding the rationale for early and aggressive treatment, every

clinician and patient should be aware of the critical importance of nonpharmacological

modalities that include patient education, physical activity, and appropriate rest, as well

as physical, occupational, and dietary therapy; this may include the use of devices to

protect joints and their function. Diligent adherence to both nonpharmacological and

pharmacological treatments is vital for patients to receive the benefits of each.

Pharmacists play a critical role in adherence to all forms and modalities of treatment

and should take this responsibility seriously.

Despite the best intentions of medical teams treating and researching RA, gaps in

care persist. Although a great number of patients with RA are helped substantially by

the available therapies, an estimated 30% of patients with RA, usually those with the

most severe forms of the disease, do not demonstrate a response to any treatment. In

addition, adverse effects may limit the usefulness of certain agents.17 Ensuring patient

adherence is always a difficult challenge, especially with injected therapies and

multidrug regimens.17,18

A recent large-scale study investigating the needs of RA patients (Developing

Superior Understanding of RA Patients’ Needs [DESIGN]) was conducted to explore the

attitudes and behaviors of RA patients and health care providers regarding the disease

and its treatment.19 The findings, reported during the 2008 ACR Annual Scientific

Meeting, showed that 37% of United States (U.S.)-based patients were dissatisfied or

extremely dissatisfied with their level of pain from RA. Only 9% of U.S. patients

responded that they were satisfied or extremely satisfied. These findings demonstrate

that pain control remains an extensive unmet need in RA disease management efforts,

study investigators concluded.

The survey also identified educational gaps associated with RA. For example, the

vast majority of physicians (87%) and nurses (90%) surveyed regarded their patients as

having a high level of RA knowledge, while only 50% of patients said their knowledge

level was high.19

Another RA patient needs survey entitled RAISE (Rheumatoid Arthritis: Insights,

Strategies and Expectations), whose results were revealed at the 2009 ACR Annual

Scientific Meeting, showed that biologic users reported substantially more good days

per month than those not using biologic therapies for RA, but that 22% experienced

high levels of pain.20 Among those not using biologic therapies for RA, 62% were not

aware of this therapeutic option (despite being eligible) and 88% had never had it

recommended by a clinician.20

Current Management Approaches

Review of Classes

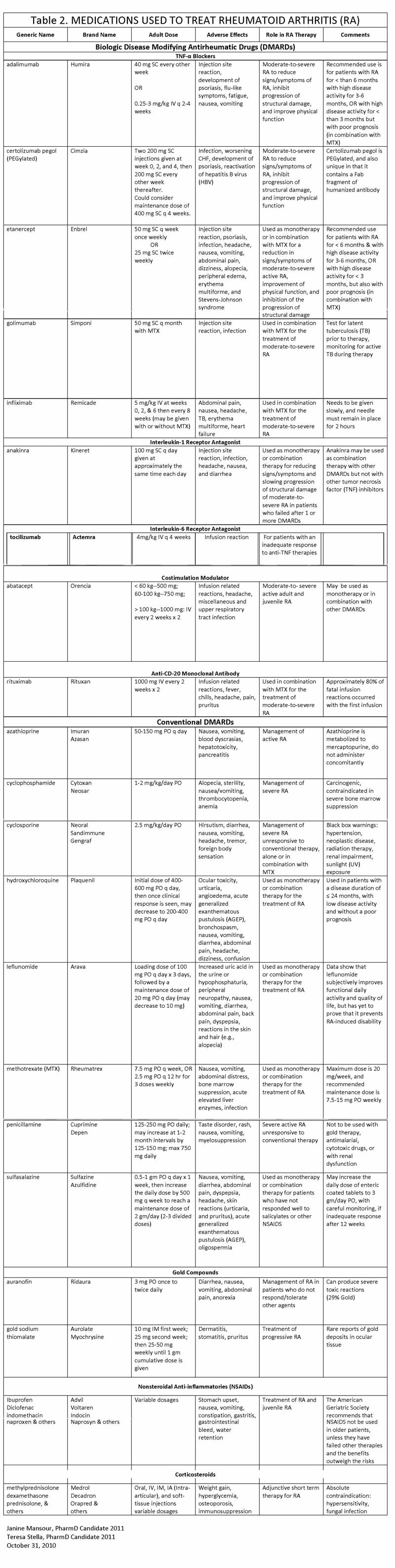

There are 3 general broad categories of medications used to treat RA: 1) anti-inflammatory agents, which include NSAIDs and corticosteroids; 2) disease-modifying

antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs); and 3) biologic DMARDS, also known as biologic

response modifiers (BRMs) or biologics. (See Table 2)

Anti-inflammatory Agents

Historically, anti-inflammatory agents for the treatment of RA include NSAIDs and corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), which were at

one time the first-line agents for the treatment of RA. During the past decade, though, it

was realized that both NSAIDs and corticosteroids, while effective for treating pain and

inflammation, did little to slow the progression of the disease. Therefore, DMARDS have

become the recommended first-line choice, with the use of NSAIDs and/or

glucocorticoids used concomitantly only to quell pain and inflammation without the

benefit of halting or slowing the course of the disease.21

DMARDs

DMARDS are often used as first-line treatment for newly diagnosed disease and

include methotrexate, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, and sulfasalazine. At one time, in addition to the aforementioned DMARDs, azathioprine, D-penicillamine, gold

compounds, minocycline, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide were used as second-or third-line treatments, but, because of concerns about questionable efficacy and the

more profound risk of toxicity, these DMARDs are less frequently used today.11,16

Currently, it is much more likely that a combination oral therapy with safer agents or the

combination of a single oral agent and an injectable BRM would be used in conjunction

with common dual therapies, such as methotrexate and etanercept or methotrexate and

infliximab. Combination oral therapies, such as methotrexate plus sulfasalazine or

methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine, in particular, are also effective dual oral DMARD

therapeutic approaches.22

Methotrexate

Methotrexate is a folate antagonist that suppresses purine biosynthesis, inhibits

cytokine production, and stimulates adenosine production, all of which contribute to its

anti-inflammatory action. Symptomatic relief is often achieved in the first month of

therapy and methotrexate is associated with persistence of use in many patients. In

addition to being used orally, methotrexate can be injected intramuscularly or

subcutaneously, however the most common route of administration is oral. Monitoring of

therapy is reviewed in Table 1. Common side effects of methotrexate include nausea,

vomiting, and abdominal distress, all of which are often self-limiting when used at

antirheumatic dosages. Paradoxically, rheumatoid nodules can increase in size with

methotrexate therapy.23

The one particular aspect of methotrexate therapy that pharmacists must be

aware of concerns the addition of folic acid to the regimen of a patient using

methotrexate. Folic acid will decrease the likelihood of toxicity and improve the side

effect profile and will not, in any way, compromise the response to therapy; so, if a

pharmacist is working with an RA patient currently on methotrexate and not using folic

acid; the patient’s prescriber should be contacted to determine if concomitant therapy

with folic acid was inadvertently overlooked.

Leflunomide

In contrast to methotrexate, which alters purine synthesis, leflunomide is a

DMARD that inhibits pyrimidine synthesis, thereby altering lymphocyte activation and

decreasing the inflammatory response. See Table 1 for monitoring guidelines.

Methotrexate and leflunomide are equally efficacious. An unusual caveat to leflunomide

therapy is that pregnancy should be avoided because leflunomide is teratogenic and

precautions against pregnancy must be taken, by both men and women, on therapy.

Leflunomide undergoes enterohepatic circulation and, therefore, in cases of toxicity or in

patients desiring to conceive a child, cholestyramine is required to quickly bring down

blood levels; without this strategy it would take months to remove this drug from the

body.24

Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine is one of the safest oral DMARDs for the treatment of RA,

being devoid of myelosuppression and renal or hepatic toxicity and with ophthalmologic

toxicity approaching zero; however, routine ophthalmological evaluation is

recommended.25 Side effects tend to be mild, with vomiting, nausea, or diarrhea easily

lessened by administration with food. One of the drawbacks of hydroxychloroquine is it

may take up to 6 months for patients to respond and, in general, if no response is

experienced between 6 and 9 months, the drug should be discontinued.

Sulfasalazine

Sulfasalazine is not active until it is cleaved by intestinal bacteria to sulfapyridine

and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA). Therefore sulfasalazine is a prodrug with the active

metabolite thought to be sulfapyridine. 26 Antirheumatic response if often seen within 2

months; however, unlike methotrexate, its persistent use is frequently hindered by

intolerable side effects which include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and anorexia.

Monitoring parameters are summarized in Table 1. An important counseling point for

pharmacists is to relay to patients using sulfasalazine is that it may turn their skin or

body fluids a yellow-orange color, but this is of no clinical consequence. Furthermore,

sulfasalazine can bind iron and its absorption can be decreased if antibiotics destroy the patient’s intestinal microflora. Both of the former points are important for pharmacists to

communicate to their patients on sulfasalazine therapy.

Newer Options: Biologic DMARDs/BRMs

There are 5 basic categories of biologic DMARDs/BRMs (see Table 2): 1) TNF

antagonists; 2) IL-1 receptor antagonists; 3) IL-6 receptor antagonists; 4) costimulation

blockers; and 5) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. All of the commercially available

biologic DMARDs are genetically developed protein molecules that have various actions

on the pathogenesis of RA. One of the distinct advantages of the biologic DMARDs are

that they do not require routine laboratory monitoring (see Table 1); however biologic

DMARDs generally do increase the likelihood of infection and all therapy must be

temporarily suspended if the patient experiences an acute infection. Furthermore, as

these agents may increase the risk of tuberculosis, all patients should receive a

tuberculin skin test evaluation prior to use.16 Theoretically, TNF inhibitors may pose the

risk of malignancies; however, there are no data substantiating or supporting this and

continued postmarketing surveillance is necessary.16 Before we review some specifics

of each of the various biologic DMARDs, let’s briefly touch on a few general RA

treatment updates.

Treatment Updates

Increasing interest has been focused on the use of antibodies and antibody

fragments as the basis for new therapies to combat chronic disease.27 An example

relevant to RA is the use of agents that downregulate the function of TNF-alpha (TNF-α), a key cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of RA. Anti-TNF-α agents have been

shown to minimize and, in some cases, halt the progression of joint destruction.

Although anti-TNF-α agents for RA do not increase the risk for serious adverse events

at recommended doses, higher doses are associated with an increased risk of serious

infections.28 Selection of the appropriate anti-TNF-α agent for an RA patient is a critical,

but complex, decision for clinicians. Advances in biotechnology have made it possible to

engineer biologic therapies that harness the functional capabilities of many types of

proteins, including enzymes, hormones, cytokines, and antibodies.29,30 One method that has proven successful for overcoming the inherent limitations of proteins used as drug

therapy is to covalently join the protein with polyethylene glycol (PEG), a nontoxic,

nonimmunogenic polymer approved by the FDA for use in foods, cosmetics, and

pharmaceuticals.31 Conjugation with PEG (termed PEGylation) modifies the structure

and function of the parent protein, resulting in a compound with potentially improved

therapeutic capabilities.

In general, biologic DMARDs are reserved for patients who have failed a proper

trial of standard DMARD therapy. Often, when a biologic DMARD is introduced, the

patient may remain on the oral DMARD methotrexate or, if the standard DMARD is

ineffective, the biologic DMARD would be used as sole therapy, when appropriate

(some require the coadministration of methotrexate). The decision to add or substitute

with a biologic DMARD is based on many factors, including the clinician's comfort level

with the therapy, the frequency and/or route of administration, the manual dexterity of

the patient, and the final cost to the patient; the patient’s insurance coverage will also

factor into the decision of whether to pursue biologic DMARD therapy. The ACR’s most

recent guideline statement, about the use of DMARDs to treat RA, recommends using

an anti-TNF-α agent plus methotrexate for patients who have experienced a high level

of disease activity for 3 months or longer, a poor prognosis, no barriers related to

treatment cost, and no insurance restrictions to accessing medical care.16 Pharmacists

involved in the management of RA patients should note that, in general, patients prone

to serious infections, those with a history of demyelinating disorders, such as multiple

sclerosis or optic neuritis, and patients with any degree of heart failure are not viable

candidates for biologic DMARD therapy.16

Specific Review of Biologic DMARDs for the treatment of RA

Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Antagonists

There are currently five FDA approved TNF antagonists approved for the treatment

of RA and they are etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab.

Etanercept

The first commercially available TNF-α drug was etanercept, which is a recombinant

form of the human TNF receptor, and it works by binding soluble TNF, thereby

preventing the activation of TNF receptors. Etanercept is injected subcutaneously once

or twice weekly, with self-limiting local injection site reactions being the most common

side effect. No laboratory monitoring is required and pharmacists should be aware that

patients with multiple sclerosis should not receive this drug. Multiple clinical trials of

etanercept as monotherapy have demonstrated superior slowed disease progression

when compared with methotrexate.32-34

Infliximab

Infliximab is a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF-α and requires

the coadministration of methotrexate to suppress antibody production against the

murine-derived portion of the molecule. Roughly 10% of patients develop antibodies

against infliximab, which may predispose a patient to infusion reactions or lessen the

efficacy of the drug. Infliximab requires intravenous infusion, administered by a qualified

health care provider.35 Infusion-related reactions are not uncommon and may include

rash, flushing, headache, fever, and chills, as well as tachycardia or dyspnea. Patients

experiencing an infusion reaction should temporarily discontinue the infusion, or slow

the infusion rate, and administer acetaminophen, corticosteroids, and antihistamines,

such as diphenhydramine. Patients with a history of infliximab-related infusion reactions

can be successfully pretreated with corticosteroids and antihistamines to lessen the

chance of subsequent reactions. Clinical trials involving infliximab plus methotrexate

have demonstrated superior efficacy when compared with those investigating

methotrexate monotherapy.36,37

Adalimumab

Adalimumab is a recombinant human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to both

soluble and bound TNF-α. Patients often experience symptomatic benefit within 1 to 2

weeks after use and adalimumab can be administered in combination with methotrexate

or other DMARDs. Adalimumab has shown similar efficacy to other anti-TNF-α

therapies, with local skin injection site reactions being the most common side effect.

Certolizumab

In the treatment of RA, the PEGylated anti-TNF-α agent certolizumab has been

shown to bind to and neutralize both membrane-bound and soluble human TNF-α in a

dose-dependent manner. Certolizumab is subcutaneously injected at weeks 0, 2, and 4

and then every 2 to 4 weeks thereafter. Optimal response is reported after 14 to 16

weeks of therapy; it has proven to be more effective than methotrexate

monotherapy.38,39 Most common adverse reactions are headache, nasopharyngitis, and

upper respiratory tract infection. As with other TNF-α therapies, and consistent with this

class of therapy, most serious adverse reactions involving certolizumab are infectious in

nature, including tuberculosis.

Golimumab

Golimumab is a human IgG1, kappa, monocloncal antibody TNF-α blocker therapy

that is used in combination with methotrexate. Golimumab is injected monthly and has a

similar side effect profile to other anti-TNF therapies.

IL-1 Receptor Antagonists

Anakinra

There is only one IL-1 receptor antagonist on the market and that is anakinra.

Anakinra is a recombinant form of the human IL-1 receptor; when it binds IL-1,

subsequent cell signaling is inhibited. One of the potential drawbacks of this medication

is the necessity to subcutaneously inject anakinra daily. Anakinra can be used with

DMARDs, but it should not be used with TNF antagonists because there is an increased

risk of infection with that combination and no additional clinical benefit is afforded by

adding anakinra to an anti-TNF therapy. Injection site reactions are the most common

side effect reported and the precautions regarding the serious risk of infection are

similar to those of other anti-TNF therapies. Pharmacists should be aware that, in

general, rheumatologists believe that anakinra is less efficacious than currently

available anti-TNF therapies and should be reserved for patients failing other biologic

DMARDs.40,41

IL-6 Receptor Antagonist

Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab is an IL-6 receptor-inhibiting monoclonal antibody that binds to both

soluble and membrane-bound IL-6. Tocilizumab is administered intravenously every 4

weeks and can be used as either monotherapy or in conjunction with a DMARD

(methotrexate).42 Most common side effects include upper respiratory tract infection,

nasopharyngitis, headache, hypertension, and increased alanine aminotransferase

(ALT). Infusion reactions may also occur. Tocilizumab is reserved for RA patients who

have had an unsatisfactory response to one or more anti-TNF therapies.42

Costimulation Blocker

Abatacept

Abatacept, the only costimulation blocker on the market, works by binding to

CD80/CD86 receptors on antigen-presenting cells, thereby preventing T cell activation.

In patients with RA, when T cells are activated they facilitate the inflammatory process

and promote cytokine production and T cell proliferation. Abatacept is reserved for

patients who have had an unfavorable response to anti-TNF therapies. Abatacept is

administered initially as 2 infusions every 2 weeks and, then, as two infusions every 28

days; side effects are mainly related to infusion reactions. Roughly only 50% of the

patients receiving abatacept have an acceptable response.43

Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody

Rituximab

Rituximab is a genetically engineered chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and

is reserved for patients with moderate-to-severe RA who have inadequately responded

to conventional DMARDs and other biologic DMARDs.44 Rituximab works by depleting B

lymphocytes. Two infusions are given 2 weeks apart, and its prolonged effect on B cells

results in a prolonged duration of action. Methylprednisolone, acetaminophen, and

antihistamines are commonly given prior to the infusion to reduce the risk and

seriousness of infusion-related reactions. Rituximab possesses a black box warning of fatal infusion reactions and severe mucocutaneous reactions. Side effects include labile

blood pressure, cough, rash, and pruritus. Rituximab is reserved for patients who have

failed anti-TNF therapies.44

Latest Data on Certolizumab in Patients With RA

Reports from the ACR’s 2009 Annual Scientific Meeting included updates from trials

investigating the efficacy and safety of certolizumab plus methotrexate for RA. A study

by Keystone and colleagues demonstrated that patients who responded positively in the

first 6 weeks of treatment to the combination of certolizumab and methotrexate were

also more likely to have better outcomes after 1 year (i.e., ACR responder rates,

physical function, pain relief) versus those who were not early responders.45 Similarly,

data from Westhovens et al showed that early responders also enjoyed improved

household productivity compared with those who responded later to certolizumab.46

These studies, along with others presented at the meeting, continue to support the

theory that the time to initial response and the level of early response to this anti-TNF-α

combination are strong predictors of 1-year therapeutic outcomes. As with other biologic

DMARDs and for certolizumab, clinicians making treatment decisions on behalf of their

patients with RA, it is important to recognize that the majority of patients who are going

to respond will do so within the first 12 weeks of treatment. 47 Clinical improvements in physical function and health-related quality of life were

sustained for more than 2 years in patients receiving certolizumab-methotrexate.48

Furthermore, infections were the most commonly reported adverse event; the rate of

serious infection was 5.4 per 100 patient-years.49

Strategies for Enhancing Patient Outcomes

Effective, patient-centered and individualized counseling is required for patients with

this chronic incurable condition. General counseling highlights include, but are not

limited to, the following 4 points: 1) stress the need for routine and constant consultation

with a rheumatologist because RA treatment is rapidly advancing; 2) stress the

importance of reporting any changes in general health because changes may be a sign

of disease progression or medication side effects; 3) stress the importance of regular evaluation and treatment by a physical therapist and occupational therapist, when

appropriate; and 4) stress the importance of weight reduction, rest, and the appropriate

use of assistive devices.

Tight Control of RA

“Tight control” has been defined as a treatment strategy tailored to the individual

patient, whereby a predefined level of low disease activity or remission, within a certain

period of time, is designated as a goal to be achieved.50 A number of recent studies

have shown significant benefits for the tight control, or intensive outpatient management

of RA, in comparison with routine care.51-53 For example, in a Japanese study of 91

patients with RA who were treated using anti-TNF agents for the duration of 1 year, the

benefits of tight control included the reduced need for joint surgery.51

Tight control of RA may involve more frequent monitoring of the patient, or it may

include monitoring in combination with a protocol for treatment adjustments. Results of

a meta-analysis presented at the 2009 ACR/ARHP Annual Scientific Meeting showed

that the latter approach (monitoring in combination with a treatment protocol) was “far

more effective than usual care,” while tight control involving monitoring was found to be

only slightly more effective.54

The BeSt trial, a randomized clinical trial involving 508 recently diagnosed RA

patients, compared effectiveness among the following 4 different treatment approaches:

sequential monotherapy; step-up combination therapy; initial combination therapy with

methotrexate, plus high-dose prednisone; or infliximab in combination with

methotrexate. The combination therapies were associated with less radiologic damage

after 1 year than the other 2 strategies and with greater functional improvement.55

Switching Therapy

Among people receiving biologic agents, such as anti-TNF-α agents for their RA,

many either do not respond to or have a suboptimal response to therapy.56 For those

patients with RA who respond well initially, treatment may lose efficacy over time;

because various anti-TNF-α agents differ in chemical structure, mechanism, and safety

profile, it is reasonable to consider switching from one anti-TNF agent to another as a viable approach for those who fail or are intolerant to the initial treatment.57 In an Italian

study of patients switched from one anti-TNF agent to another, the proportion of

patients with good and moderate-good response increased from 5.4% before the switch

to 27% 3 months after the switch (P <.000001).56

Productivity Outcomes in RA Studies

Reduced productivity and a compromised quality of life are realistic outcomes for

those with RA. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey indicated that people with RA are

53% less likely to be employed and spend 3.6 times the number of days sick in bed

compared with matched controls.58-61 Treatment with combination certolizumab and

methotrexate was shown in the recent studies RAPID 1 and RAPID 2 (Rheumatoid

Arthritis Prevention of Structural Damage) to increase workplace productivity and

reduce absenteeism when compared with methotrexate therapy alone. Improvements

were seen as early as 4 weeks and were sustained over time, with certolizumab-treated

patients reporting 1 day lost per month by week 52, versus 4.5 days per month for

methotrexate monotherpy.62 Productivity in the home was also improved in these trials.

Demonstrating increased productivity helps support arguments for the cost-effectiveness of biologic agents for the treatment of RA.59

Conclusion

Management of RA has been a rapidly evolving area of clinical practice during the

past 2 decades and pharmacists play a critical role in providing current education

regarding the ever-changing approach to treating patients with this common systemic

inflammatory condition. Patients are being treated far earlier and more aggressively with

different agents upon or shortly after diagnosis. Keeping abreast of these

pharmacotherapeutic changes, while being aware of individual patient needs and

potential gaps in management, remains a challenge for pharmacists involved in

managing patients with RA. However, this provides a unique, albeit challenging,

opportunity for continuing education activities that describe current knowledge of RA to

both patients and medical providers.

REFERENCES

- Harris ED. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Gabriel SE, Budd RC,

Firestein GS, et al, eds. Kelley’sTextbook of Rheumatology. 7th ed (e-dition in 2

volumes). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2004:1043-1078.

- Smith JB, Haynes MK. Rheumatoid arthritis-a molecular understanding. Ann

Intern Med. 2002;136(12):908-922.

- Jäntti J, Aho K, Kaarela K, Kautiainen H. Work disability in an inception cohort of

patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis: a 20 year study. Rheumatology.

1999;38(11):1138-1141.

- Karonitsch T, Aletaha D, Boers M, et al. Methods of deriving EULAR/ACR

recommendations on reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with

rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(10):1365-1373.

- Mikuls TR, Cerhan JR, Criswell LA, et al. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption

and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Iowa Women's Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(1):83-91.

- Khuder SA, Peshimam AZ, Agraharam S. Environmental risk factors for

rheumatoid arthritis. Rev Environ Health 2002;17(4):307-315.

- Merlino LA, Curtis J, Mikuls TR, et al; and the Iowa Women’s Health Study.

Vitamin D intake is inversely associated with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the

Iowa Women's Health Study. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50(1):72-77.

- Firestein GS. Etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Gabriel SE,

Budd RC, Firestein GS, et al, eds. Kelley’sTextbook of Rheumatology. 7th ed (e-

dition in 2 volumes). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2004:996-1042.

- Colglazier CL, Sutej PF. Laboratory testing in rheumatic diseases: a practical

review. South Med J. 2005;98(2):185-191.

- Fuchs HA, Kaye JJ, Callahan LF, et al. Evidence of significant radiographic

damage in rheumatoid arthritis within the first 2 years of disease. J Rheumatol.

1989;16(5):585-591.

- O’Dell JR. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(25):2591-2602.

- Rantalaiho V, Korpela M, Hannonen P, et al; for the FIN-RACo Trial Group. The

good initial response to therapy with a combination of traditional disease-

modifying antirheumatic drugs is sustained over time: the eleven-year results of

the Finnish rheumatoid arthritis combination therapy trial. Arthritis Rheum.

2009;60(5):1222-1231.

- Puolakka K, Kautianen H, Möttönen T, et al. Impact of initial aggressive drug

treatment with a combination of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs on the

development of work disability in early rheumatoid arthritis: a five-year

randomized follow-up trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(1):55-62.

- Smolen JS, Van Der Heijde DM, et al; for the Active-Controlled Study of Patients

Receiving Infliximab for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis of Early Onset

(ASPIRE) Study Group. Predictors of joint damage in patients with early

rheumatoid arthritis treated with high-dose methotrexate with or without

concomitant infliximab: results from the ASPIRE trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;

54(3):702-710.

- Aletaha D, Funovits J, Keystone EC, Smolen JS. Disease activity early in the

course of treatment predicts response to therapy after one year in rheumatoid

arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(10):3226-3235.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al; for the American College of

Rheumatology. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for

the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in

rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008:59(6):762-784.

- Schwartzman S, Morgan GJ Jr. Does route of administration affect the outcome

of TNF antagonist therapy? Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(suppl 2):S19-S23.

- George J, Elliott RA, Stewart DC. A systematic review of interventions to improve

medication taking in elderly patients prescribed multiple medications. Drugs

Aging. 2008;25:307-324.

- MediLexicon International Ltd. Better Interaction And Education Between

Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients and Care Providers Needed, New Study Indicates.

Medical News TODAY.com Web site.www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/127188.php. Accessed October 28, 2008.

- McInnes IB, Combe B, Burmester GR. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Insights, Strategies

and Expectations: Global Results of the RAISE Patient Needs Survey. Presented

at the 2009 Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of

Rheumatology/ARHP. Philadelphia, PA; October 18-21. Poster # 328

(Presentation #1595).

- Goldbach-Mansky R, Lipsky PE. New concepts in the treatment of rheumatoid

arthritis. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:197-216.

- Verhoeven AC, Boers M, Tugwell P. Combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis

arthritis: updated systematic review [comment]. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(6):612-

619.

- Kremer JM. Methotrexate and emerging therapies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am.

1998;24(3):651-658.

- Prakash A, Jarvis B. Leflunomide: a review of its use in active rheumatoid

arthritis. Drug. 1999;58(6):1137-1164.

- Maturi RK, Folk JC, Nichols B, et al. Hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Arch

Ophthalmol. 1999;117(9):1262-1263.

- Rains CP, Noble S, Faulds D. Sulfasalazine. A review of its pharmacological

properties and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 1995;50(1):137-156.

- Chapman AP. PEGylated antibodies and antibody fragments for improved

therapy: a review. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(4):531-545.

- Kievit W, Adang EM, Fransen J, et al. The effectiveness and medication costs of

three anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha agents in the treatment of rheumatoid

arthritis from prospective clinical practice data. Ann Rheum Dis.2008;67(9):1229-1234.

- Veronese FM, Mero A. The impact of PEGylation on biological therapies. BioDrugs. 2008;22(5):315-329.

- Fishburn CS. The pharmacology of PEGylation: balancing PD with PK to

generate novel therapeutics. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97(10):4167-4183.

- Harris JM, Chess RB. Effect of pegylation on pharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug

Discov. 2003;2(3):214-221.

- Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, et al. A comparison of etanercept and

methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med.2000;343(22):1586-1593.

- Genovese MC, Kremer JM. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with etanercept. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30(2):311-328.

- Blumenauer B, Judd M, Cranney A, et al. Etanercept for the treatment of

rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003(3):CD004525.

- Maini SR. Infliximab treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30(2):329-347, vii.

- Maini RN, Taylor PC. Anti-cytokine therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Annu Rev

Med. 2000;51:207-229.

- Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al; for the Anti-Tumor Necrosis

Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group.

Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J

Med. 2000;343(22):1549-1602.

- Keystone E, Heijde D, Mason D Jr, et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate

is significantly more effective than placebo plus methotrexate in active

rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a fifty-two week, phase III, multicenter,

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis

Rheum. 2008;58(11):3319-3329.

- Smolen J, Landewé RB, Mease P, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab

pegol plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: the RAPID 2 study. A

randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):797-804.

- Calabrese LH. Anakinra treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann

Pharmacother. 2002;36(7-8):1204-1209.

- Cohen SB. The use of anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, in the

treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30(2):365-380,

vii.

- Cada DJ, Levien TL, Baker DE. Tocilizumab. Hosp Pharm. 2010;45(6):484-492.

- Genovese MC, Becker JC, Schiff M, et al. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis

refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med.2005;353(11):1114-1123.

- Smolen JS, Keystone EC, Emery P, et al. Consensus statement on the use of

rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(2):143-

150.

- Keystone EC, Curtis JR, Fleischmann R, et al. A Faster Clinical Response to

Certolizumab Pegol (CZP) Treatment Is Associated with Better 52-week

Outcomes in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Presented at the 2009

Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology/ARHP.

Philadelphia, PA; October 18-21. Poster # 340 (Presentation # 989).

- Westhovens R, Strand V, Keystone EC, et al. A Faster Clinical Response to

Certolizumab Pegol Treatment Is Associated with Better Improvements in

Household Productivity in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Presented at the

2009 Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology/ARHP.

Philadelphia, PA. October 18-21. Poster # 72 (Presentation # 721).

- van der Heijde DMFM, Schiff M, Keystone EC, et al. Probability to Achieve Low

Disease Activity at 52 Weeks in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Patients Treated with

Certolizumab Pegol (CZP) Depends on Time to and Level of Initial Response.

Presented at the 2009 Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of

Rheumatology/ARHP. Philadelphia, PA. October 18-21. Poster # 343

(Presentation # 992).

- Strand V, Purcaru O, Kavanaugh A. Work Productivity Measures as Treatment

Goals Beyond Signs and Symptoms. Presented at the 2009 Annual Scientific

Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology/ARHP. Philadelphia, PA.

October 18-21. Poster # 64 (Presentation # 64).

- van Vollenhoven RF, Smolen JS, Schiff M, et al. Safety Update on Certolizumab

(CZP) in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis. Presented at the 2009 Annual

Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology/ARHP. Philadelphia,

PA. October 18-21. Poster # 432 (Presentation # 1699).

- Bakker MF, Jacobs JW, Verstappen SM, Bijlsma JW. Tight control in the

treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: efficacy and feasibility. Ann Rheum Dis.

2007;66(suppl. 3):ii56-ii60.

- Sano H, Arai K, Murai T, et al. Tight control is important in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis treated with an anti-tumor necrosis factor biological agent:

prospective study of 91 cases who used a biological agent for more than 1 year. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19(4):390-394.

- Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control

for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled

trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9430):263-269.

- van Tuyl LH, Lems WF, Voskuyl AE, et al. Tight control and intensified COBRA

combination treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis: 90% remission in a pilot trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1574-1577.

- Schipper LG, van Hulst LT, Hulscher MEJ, et al. Meta-Analysis of Tight Control

Strategies in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Protocolized Treatment Has Additional Value

with Respect to Clinical Outcome. Presented at the 2009 Annual Scientific

Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology/ARHP. Philadelphia, PA.

October 18-21. Poster # 354 (Presentation # 1621).

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Comparison of

treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern

Med. 2007;146(6):406-415.

- Scrivo R, Conti F, Spinelli FR, et al. Switching between TNFalpha antagonists in

rheumatoid arthritis: personal experience and review of the literature. Reumatismo. 2009;61(2):107-117.

- Keystone EC. Switching tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: an opinion. Nat Clin

Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2(11):576-577.

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Huang XY, Globe DR. Influence of rheumatoid

arthritis on employment, function, and productivity in a nationally representative

sample in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(3):544-549.

- Bejarano V, Quinn M, Conaghan PG, et al; and the Yorkshire Early Arthritis

Register Consortium. Effect of the early use of the anti-tumor necrosis factor 6adalimumab on the prevention of job loss in patients with early rheumatoid

arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1467-1474.

- Strand V, Singh JA. Newer biological agents in rheumatoid arthritis: impact on

health-related quality of life and productivity. Drugs. 2010;70(2):121-145.

- Birnbaum H, Shi L, Pike C, et al. Workplace impacts of anti-TNF therapies in

rheumatoid arthritis: review of the literature. Expert Opin Pharmacother.

2009;10(2):255-269.

- Kavanaugh A, Smolen JS, Emery P, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol with

methotrexate on home and work place productivity and social activities in

patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 15;61(11):1592-

1600.

Back to Top

|