Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Pharmacists, opioid safety, take-home naloxone, and preventing overdose

Introduction

Drug overdose is a major public health crisis, with opioid overdose deaths increasing fourfold between 2000 and 2014, claiming more than 28,000 lives in 2014 alone. After rising for more than a decade, the number of prescription drug overdoses declined slightly in 2012 and remained steady in 2013. However, heroin overdoses have sharply increased since 2010. Unfortunately, recent mortality data for 2014 show that “nearly every aspect of the opioid overdose death epidemic worsened in 2014.”1

Evidence-based opioid overdose prevention strategies include opioid prescriber education, access to medication-assisted substance use disorder treatment, and overdose education with take-home naloxone.

Many national healthcare associations (e.g., American Pharmacists Association,2 American Public Health Association,3 American Medical Association,4 American Society of Addiction Medicine,5 National Association of Boards of Pharmacy,6 American Association of Poison Control Centers7) support expanded access to and use of naloxone for overdose rescue.

Pharmacists are the public’s most accessible medication safety experts. They have extensive knowledge about prescription opioid medications (e.g., indication, mechanism of action, dosage, adverse drug reactions, drug interactions). For this reason, pharmacists are ideally situated to decrease opioid overdose deaths through education and provision of naloxone.8 Through the use of collaborative practice agreements, pharmacist prescriptive authority, standing orders, and other creative models, pharmacists can implement strategies in their communities to prevent deaths from opioid overdoses.

Pharmacists can play an essential role in implementing the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s five strategies to prevent overdose deaths:9

Strategy 1: Encourage providers, persons at high risk, family members, and others to learn how to prevent and manage opioid overdose.

Strategy 2: Ensure access to treatment for individuals who are misusing or addicted to opioids or who have other substance use disorders.

Strategy 3: Ensure ready access to naloxone.

Strategy 4: Encourage members of the public to call 911 when an overdose occurs.

Strategy 5: Encourage providers to use state Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs).

Epidemiology

Chronic pain and associated activity limitations and diminished quality of life affect approximately 100 million Americans. Although many treatments are available for chronic pain, an estimated 5 to 8 million people use opioid pain medication for longer than 90 days.10 The number of opioid prescriptions dispensed from U.S. retail pharmacies grew from 76 million in 1991 to 216 million in 2012.11

| Common prescription opioids12 |

| Generic |

Brand name |

| Hydrocodone |

Vicodin, Lorcet, Lortab, Norco, Zohydro |

| Oxycodone |

Percocet, OxyContin, Roxicodone, Percodan |

| Morphine |

MS Contin, Kadian, Embeda, Avinza |

| Codeine |

Tylenol with Codeine, TyCo, Tylenol #3 |

| Fentanyl |

Duragesic, Sublimaze, Fentora |

| Hydromorphone |

Dilaudid, Exalgo |

| Oxymorphone |

Opana |

| Meperidine |

Demerol |

| Methadone |

Dolophine, Methadose |

| Buprenorphine |

Suboxone, Subutex, Zubsolv, Bunavail, Butrans |

Prescription opioids are important, effective, yet potentially dangerous medicines. Every year, unintentional overdose deaths occur among people who take opioids as prescribed, people who use opioids nonmedically (i.e., misuse/abuse), and people who have developed an opioid use disorder.

Between 2000 and 2014 nearly a half million people died from drug overdoses (also called poisonings) in the United States, and the rate of opioid overdose has tripled in that time.1 Drug overdoses have overtaken motor vehicle crashes to become the leading cause of unintentional injury deaths. The New York Times13 developed a graphic based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)14 that shows the change in overdose death rates between 2003 and 2014, which is the most recent year for which fatality data are available.

|

In 2012, for the first time in more than a decade, the number of prescription opioid-related overdose deaths dropped compared with the previous year; in 2013, the number held relatively steady. Some public health officials were optimistic that this represented a turn of the tide for opioid-poisoning fatalities. Unfortunately, 2014 saw a surge in overdose deaths; of the 47,055 drug overdose deaths in 2014 (the most recent year these data are available) more than 60% involved opioids, including heroin.1 According to CDC:

The 2014 data demonstrate that the United States' opioid overdose epidemic includes two distinct but interrelated trends: a 15-year increase in overdose deaths involving prescription opioid pain relievers and a recent surge in illicit opioid overdose deaths, driven largely by heroin.1

The latter trend may be explained by people with a prescription opioid use disorder transitioning to heroin. Comparing cohorts of heroin users in the 1960s with more recent heroin users, 80% of the former group report that their first opioid of abuse was heroin, whereas 75% of more recent heroin users say that their first opioid of abuse was a prescription opioid.15

| Drug overdose deaths* involving opioids,†,§ by type of opioid¶ –United States, 2000–2014 |

|

Source: National Vital Statistics System,

Mortality file.1

* Age-adjusted death rates were calculated by applying age-specific death rates to the 2000 U.S. standard population age distribution.

† Drug overdose deaths involving opioids are identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, underlying cause-of-death codes X40–X44, X60–X64, X85, and Y10–Y14 with a multiple cause code of T40.0, T40.1, T40.2, T40.3, T40.4, or T40.6.

§ Opioids include drugs such as morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, heroin, methadone, fentanyl, and tramadol.

¶ For each type of opioid, the multiple cause-of-death code was T40.1 for heroin, T40.2 for natural and semisynthetic opioids (e.g., oxycodone and hydrocodone), T40.3 for methadone, and T40.4 for synthetic opioids excluding methadone (e.g., fentanyl and tramadol). Deaths might involve more than one drug, thus categories are not exclusive. |

Opioid overdose risks and considerations

Although any person using any opioid for any reason is a good candidate for opioid safety education, there are specific health-related, circumstantial, and/or behavioral situations that may increase overdose risk.16

Situations that can increase overdose risk include the following:

- Dispensing high dose opioids (more than 50 morphine milligram equivalent [MME] daily)

- Examples of opioid regimens that are more than 50 MME include–

- Methadone 10 mg by mouth every 12 hours = 60 MME

- Oxycodone 10 mg by mouth every 6 hours = 60 MME

- Hydrocodone 10 mg by mouth every 4 hours = 60 MME

- Fentanyl 25 mcg patch every 72 hours = 60 MME

- Duration of opioid use for more than 90 days

- Overlapping opioid prescriptions

- Using methadone for pain

- Rotating from one opioid to another because of incomplete cross-tolerance

- Concomitant opioid–alcohol use

- Additional prescriptions for benzodiazepines and other central nervous system (CNS) depressants

- A person takes an opioid as directed, but the prescriber miscalculated the opioid dose

- Taking opioids other than prescribed or nonmedically

- Patient misunderstands the directions for use

- Communities where first responders take a longer time than usual to respond to 911 calls (e.g., rural areas, insufficient geographic data)

Health conditions that have been associated with increased overdose risk include the following:

- Hepatic, pulmonary, or renal dysfunction

- Mental health conditions

- Previous overdose, bad reaction to opioids, or ever having received emergency medical care involving opioids

- Substance use disorder

Pharmacists should consider several unique risks for elderly patients:17

- Drug–drug interactions in complicated pharmaceutical regimens

- Drug–disease interactions, particularly in the case of–

- Congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea, chronic liver disease, or renal disease

- Dementia

- Decline in therapeutic index, possibly resulting in dose escalation

- Age-related predisposition to adverse drug effects

- Increases in fall risks

There are several unique opioid considerations with adolescent patients and their caregivers:

- Naloxone is a unique prescription medicine in that it is indicated as emergency therapy wherever opioids may be present.18, 19 The implication is that parents who suspect that their child may be using opioids nonmedically should have immediate access to naloxone.

- Using opioids without an established tolerance (i.e., casual or intermittent use) carries a unique overdose risk. Someone without an established tolerance is more vulnerable to dosing variation. For example, visually, there is very little difference between a generic pill containing 5 mg of hydrocodone and one containing 10 mg of hydrocodone. However, the difference in either relatively low dose in an opioid naïve person could be the difference between an overdose or no overdose, especially if additional substances are present that increase the risk of respiratory depression.

- Whether opioid use is exactly as prescribed or nonmedical, caregivers for adolescents should know about opioid safety and naloxone kits and have them available (if patient, caregiver, or provider deems necessary), similar to having an epinephrine injector to manage anaphylaxis for known hypersensitivity.

Any patient with a known or suspected substance use disorder could be at risk for an overdose. Although this is not in and of itself a reason not to dispense prescribed opioid medications, there are several situations to consider that increase overdose risk in these patients:

- Combining opioid pain relievers with medicines to treat substance use disorders, such as buprenorphine or methadone

- Entry into (induction period) or exit out of medication assisted treatment for a substance use disorder

- Changes in tolerance, such as a recent engagement with treatment or incarceration

- Nonmedical use of prescription opioids, benzodiazepines, or other sedating substances

- Using illicit drugs with unknown purity, such as heroin

- Injecting prescription or illicit opioids

- Using substances while alone

Naloxone

Naloxone was patented in 1961, was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1971, and is currently on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines.

Naloxone hydrochloride is a pure opioid antagonist that competitively binds to μ-opioid receptors only when opioids are present and bound at the receptor site. Naloxone demonstrates no effect on mu, kappa, or delta receptors in a person who has not taken opioids. No tolerance or dependence is associated with naloxone use.20–22 The reversal of opioid toxicity with naloxone is dose dependent. Individuals who have used a particularly potent opioid (e.g., fentanyl), have high concentration of opioids in their system, or have used a long-acting opioid may require more frequent and/or larger doses of naloxone to reverse symptoms.21 When comparing the μ-opioid receptor affinity of naloxone with that of most opioids, including heroin, naloxone has a greater affinity to bind to the receptor site. This mechanism allows naloxone to remove the opioid from the receptor site and then bind it more securely.20, 21 When this occurs, respiratory depression resolves partially or fully (depending on the amount, form, and route of opioids taken), hypotension resolves, and CNS depression abates.20–22 Depending on the type of opioid used, the individual may be at risk for experiencing rebound opioid toxicity and/or acute respiratory depression because of the short duration of activity of naloxone (i.e., 30–90 minutes).20 This effect most often occurs when an individual has taken a long-acting opioid such as methadone or extended-release oxycodone.21 Naloxone’s short duration of action is an important reason to convey to patients that receiving emergency medical care for an opioid overdose is important, even if the person has responded to the naloxone.

Effects resulting from naloxone administration include potentiating opioid withdrawal (ranging from common and mild symptoms of flu and malaise to significant but rare symptoms of severe agitation), hypertension, and return of pain.21–23 The severity of withdrawal symptoms depends on the amount and type of opioids present in the body when naloxone is administered. Case reports document pulmonary edema in patients with current respiratory disease following naloxone administration.24 Paradoxically, other case reports demonstrate reversal of pulmonary edema after naloxone administration.25,26 Rare case reports of serious adverse events such as seizures, arrhythmia, and hypertensive reactions exist but are difficult to interpret because opioid toxicity and hypoxemia resulting from respiratory depression can manifest the same symptoms.27–30 Many individuals who simultaneously take opioids with stimulants, such as cocaine or amphetamines, are predisposed to hypertension once the opioid toxicity is reversed.29,30 Severe agitation of individuals is an uncommon reaction related to naloxone administration (7%)31 and is even more uncommon in community-based and take-home naloxone settings.32

Naloxone is not effective in treating overdoses of non-opioid prescription medicines like benzodiazepines or barbiturates. It also is not effective in overdoses with stimulants, such as cocaine and amphetamines, or other non-opioid illicit drugs such as MDMA (Ecstasy, Molly), GHB (G), or ketamine (Special K). However, a polysubstance overdose that includes opioids warrants the use of naloxone.

Pharmacist role in expanding the scope of naloxone provision

As discussed in the introduction, myriad ways exist for pharmacists to contribute to overall opioid safety. This course focuses on naloxone, but additional continuing education courses are available on other important opioid overdose prevention strategies (see resources section).

Naloxone access via pharmacists is an emerging practice that capitalizes on pharmacists’ skills within the healthcare infrastructure. Similar to existing harm reduction services and community-based efforts, most pharmacists’ expertise is available without an appointment and at low or no cost. In addition, pharmacists are accessible, trained, and trusted healthcare providers who are in a position to augment the services and information available through community-based organizations (CBOs) and expand the reach of overdose prevention services to people who do not use existing harm reduction services but may be at risk for an overdose.33

Bailey and Wermeling suggest that pharmacists have a crucial role in detecting and mitigating overdose risk, as well as establishing policies:

Pharmacists can serve as invaluable instruments in identifying high-risk patients, particularly those with an established presence within primary care clinics and health departments because they have direct access to patients at the time of screening. All pharmacists, regardless of practice setting, can collaborate with prescribers to formulate policies and protocols for dispensing naloxone, help train providers and patients, and aid in circulating information throughout the community and the profession.8

Community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) to people who use drugs started in the United States during the late 1990s in Chicago.34 Since then, OEND had expanded to 136 programs that manage 644 naloxone distribution sites throughout the United States.35

| Number of survey respondents reporting beginning or continuing to provide naloxone kits to laypersons, by year–United States, 1996–June 2014*† |

|

*Results of a survey conducted in July 2014 by the Harm Reduction Coalition, in which 136 organizations reported 644 local sites where laypersons were trained to recognize an opioid drug overdose and provided or prescribed naloxone kits.

†As of June 2014. |

OEND programs address overdose by educating laypeople at risk for overdose and their social network how to prevent, recognize, and respond to an overdose. Participants in the program are trained to recognize signs of overdose, seek help, use naloxone, rescue breathe and/or deliver chest compressions, and stay with the person who is overdosing.

As of June 2014, 152,283 naloxone kits have been distributed and 26,463 overdose rescues have been reported in the United States.35 Studies have shown a reduction in overdose deaths concurrent with OEND implementation,34 a nearly 50% reduction in fatal overdose rates in communities that have aggressively implemented OEND,36 and a 36% reduction in the proportion of fatal overdoses among people recently released from incarceration.37 Providing naloxone rescue kits to people who are at risk for an overdose, people who use drugs, and their social networks is not associated with people using more drugs and it may be associated with an increase in accessing substance use disorder treatment.32

Although naloxone access to laypeople was conceived by drug user groups and initially implemented through syringe access and disposal programs, its evidence-based lifesaving benefit has been acknowledged. Professional organizations are calling for increased access to naloxone among several targeted populations. Models have emerged for adapting the existing healthcare infrastructure to provide naloxone using healthcare delivery mechanisms–many of which depend on pharmacists to play a pivotal role. Conventional prescriptions are an important way to expand naloxone, yet several important barriers exist when this is the only available mechanism, such as:

- Lack of providers

- Difficulty making or keeping appointments with providers

- Expense of visit to prescribers

- Prescription cost/lack of prescription drug insurance

- Fear of losing access to prescribed opioid medications

- Lack of provider knowledge about naloxone

- Liability concerns of providers

Naloxone is not a controlled substance, so prescribers do not need a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) number. It can be prescribed by any licensed prescriber as defined by state regulation–in some cases including pharmacists. Green and colleagues compared four existing pharmacy-based naloxone access models to community-based models and “traditional” prescriptions.33

| Model |

CBO naloxone distribution |

Traditional prescription |

Pharmacy-based naloxone models |

| CPA |

Standing medication order |

Protocol order |

Pharmacist prescribing |

| Who issues prescription? |

Prescriber via standing order |

Prescriber |

Non-pharmacist prescriber |

Non-pharmacist prescriber |

Licensing board |

Pharmacist |

| Medical professionals required |

Varies by state: prescriber, state/local health department |

Prescriber + pharmacist |

Prescriber + pharmacist |

Prescriber + pharmacist |

Pharmacist |

Pharmacist |

| Potential recipients |

Individuals served by the CBO |

Patients of the prescriber |

Varies by state |

Anyone meeting criteria specified by prescriber |

Anyone meeting criteria specified by licensing board |

Anyone for whom medication is indicated |

| Target overdose risk population being served |

People who use drugs (prescription opioids, heroin) who access the CBO* |

People who use drugs who are in treatment/visit a prescriber* |

People who use drugs (prescription opioids, heroin) who visit a pharmacy* |

People who use drugs (prescription opioids, heroin) who visit a pharmacy* |

People who use drugs (prescription opioids, heroin) who visit a pharmacy* |

People who use drugs (prescription opioids, heroin) who visit a pharmacy* |

| Patients prescribed opioids who are at risk of overdose* |

Patients filling a prescription for opioids at a pharmacy who are at risk of overdose* |

Patients filling a prescription for opioids at a pharmacy who are at risk of overdose* |

Patients filling a prescription for opioids at a pharmacy who are at risk of overdose* |

Patients filling a prescription for opioids at a pharmacy who are at risk of overdose* |

| Geographic reach |

Limited to where CBOs are located and operate |

Limited to where the prescriber practices |

Any participating pharmacy in the state |

Any participating pharmacy in the state |

Any participating pharmacy in the state |

Limited to where the pharmacist practices |

Source: Green, Dauria, Bratberg, Davis, and Walley.33

*A majority of states now permit prescriptions to be written for third parties (e.g., friends, staffs of organizations that provide services to individuals at risk of overdose) as well as the person at risk of overdose. CPA = collaborative practice agreement |

Opportunities for pharmacists to address opioid safety

Preventing overdose and maximizing opioid safety are important public health issues where pharmacists play a crucial role. Green and colleagues noted that not only do pharmacists directly counsel patients, provide them with education, and/or dispense naloxone, they are also active in two other complementary areas to improve opioid safety: 1) pharmacy–prescriber partnerships to better manage opioid medications, reduce overprescribing, and increase access to addiction care and 2) increasing community access to treatment of opioid use disorder with evidence-based medicines (i.e., in-pharmacy buprenorphine prescribing, daily dispensing of methadone or buprenorphine in areas with inadequate access to licensed opioid treatment programs, and in-pharmacy naltrexone injections).33

The remainder of this section describes ways to counsel and educate patients on how to prevent their own or other’s opioid overdoses. Choosing appropriate and relatable language is important. Many people may have a considerably low perception of their own risk, even if they are at high risk.38 Using the term opioid/medication safety instead of overdose risk is more descriptive of the intention and is a term with which patients can identify more readily. The San Francisco Department of Public Health offers specific language suggestions:39

- Avoid using the word overdose. Instead consider using phrases such as accidental overdose, bad reaction, or opioid safety.

- Consider telling patients that:

- Opioids can sometimes slow or even stop your breathing.

- Naloxone is the antidote to opioids. It is sprayed in your nose or injected if you have a bad reaction and can’t be woken up.

- Naloxone is for opioid medications like an epinephrine pen is for someone with an allergy.

Pharmacists should carefully assess for possible medication errors, unintended interactions, and inappropriate prescribing when dispensing prescription opioids. They should also check whether the patient had a bad reaction when taking an opioid medication and whether that reaction is similar to symptoms of overdose or withdrawal, as well as review a list of current medications for medications that increase risk of overdose. In addition to directly asking the patient if all healthcare providers know about the opioid prescription, pharmacists should check the state’s PDMP to get a complete understanding of the patient’s medication regimen and determine whether the patient is at risk of overdose from filling prescriptions at four or more pharmacies and/or from four or more providers.40,41

Even if the prescribed opioid is the only medicine the patient is taking and errors and interactions have been ruled out, educating patient about risks associated with of opioid use is warranted. Pharmacists should remind patients to take medications only as prescribed and not to mix them with alcohol or other nonprescribed medicines or drugs. Addressing other, less dangerous possible side effects such as nausea or constipation can convey caring about the patient’s overall well-being and may ease defensive concerns that the patient is being singled out or lectured to. Pharmacists should consider offering solutions for the common opioid-induced constipation, such as stimulant laxatives, along with naloxone as a solution for the relatively uncommon opioid-involved overdose.

Patients who have a substance use disorder and are receiving medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone are excellent candidates for opioid safety and overdose prevention counseling. Although methadone and naltrexone are commonly provided outside the community pharmacy setting, a pharmacist who knows that a patient has a substance use disorder diagnosis should consider discussing overdose and naloxone with that patient. Entry into and exit out of MAT are particularly vulnerable times, during which overdose risk can be addressed. What’s more, people who are engaged in MAT are in an excellent position to respond to the overdose of a friend or family member.42

Additional tips for pharmacists include the following:

- Discuss safe storage with patients to avoid both poisoning of children or pets and misuse or theft by family members or visitors. Patients can consider purchasing a lock box; some jurisdictions have dedicated public funding to subsidize costs for these boxes.

- Remind patients to take opioid medicines only as prescribed for the indicated condition and not to share prescription medications with others, even if they may have similar conditions.

- Educate patients about proper prescription drug disposal. Annually, DEA hosts a prescription medicine take-back event. Many locations organize additional take-back options, such as partnerships between pharmacy schools and communities to sponsor take-back events43–46 and installing permanent DEA-authorized collection sites at pharmacies, hospitals, and law enforcement locations.47 Opioid and several other medications48 are considered dangerous enough to warrant flushing immediately upon expiration or when the patient no longer needs the medicine if community disposal options are not immediately available. Less potentially harmful medicines may be disposed in household trash by mixing uncrushed pills with kitty litter or coffee grounds, sealing them in a plastic bag, and putting them in the trash.

- Describe the symptoms of an opioid overdose and offer the patient take-home naloxone. Encourage the patient to review these overdose symptoms and how to use naloxone with family members, friends, or others close to the patient.

- Place general awareness posters or brochures in areas where people at risk for an opioid overdose–whether a patient or not–and members of their family or social network can be exposed to important information and learn that naloxone is available. Many states used legislative and regulatory mechanisms to make naloxone available to third parties or caregivers who may be present during an overdose but are not necessarily at risk for an overdose themselves. Recent naloxone products are indicated for immediate administration where opioids may be present and focuses on actions by a potential overdose bystander, not solely by someone at risk for overdose. Making awareness materials available increases the interest of community members who do not realize that they may be in a position to help during an opioid-related emergency. Below are three examples of these types of materials:12,49,50

Overdose response education to accompany dispensed naloxone

The minimum counseling to accompany naloxone dispensing is to instruct patients on how to 1) seek emergency medical attention and follow dispatcher’s instructions for resuscitative measures (e.g., rescue breathing, chest compressions), 2) administer naloxone if the patient is unresponsive from opioid use, 3) assemble naloxone kits for administration (depending on product), and 4) include family/caregivers in patient counseling or instruct patients to train others to respond to patient’s potential overdose.

If patients are interested in additional education or have questions, the pharmacist can elaborate on several of the other important areas in this section. A major sign of possible opioid overdose is being unresponsive, but other signs include the following:

- Excessive sleepiness coupled with unresponsiveness

- Not awakening when spoken to in a loud voice or when firmly rubbing the middle of the chest

- Shallow, slow breathing (fewer than 8 breaths per minute)

- Gurgling, choking, or snoring noises

- Blue or gray lips, fingertips, and/or nail beds

Pharmacists can describe possible scenarios upon delivering a dose of naloxone to an overdose victim. For example:

- If the overdose victim does not respond to the first dose of naloxone and remains unresponsive after 3 minutes, give a second dose. All naloxone kits/products should have, at minimum, two doses of naloxone.

- The overdose victim may feel withdrawal symptoms and/or the pain that the opioids were prescribed to treat. Even if this happens, the overdose rescuer should not let the victim take more opioids. More opioids will not make the person feel better, but they could put the person at risk for rebound toxicity after the naloxone wears off.

- Naloxone lasts only 30–90 minutes, and some opioids can last for much longer. Therefore, the overdose could possibly recur. The overdose rescuer should stay with the victim for at least 3 hours or until emergency personnel arrive and assume care.

Accessing emergency medical services during an overdose is an important part of ensuring the victim survives. Because an opioid poisoning is a medical emergency, it is important to have trained medical professionals assess the condition of the overdose victim. Even if the person has responded to the naloxone and “woken up,” there may be other health problems of which the responder may not be aware. When immediately calling 911, the overdose responder must report someone is unresponsive and not breathing or struggling to breathe and give the precise address or location.

Instruction on additional resuscitative measures is usually included in most community-based take-home naloxone initiatives. Opioid overdose prevention programs in the United States generally teach rescue breathing. Some overdose prevention programs in Canada and the United Kingdom recommend chest compressions only or chest compressions with rescue breathing. The World Health Organization51 recommends rescue breathing as a priority during layperson opioid overdose response. The American Heart Association’s 2015 guidelines52 have been updated to include naloxone administration in the setting of suspected overdose and a new algorithm for “Opioid-Associated Life-Threatening Emergency” that calls for responders to administer CPR for the victim who is unresponsive with no breathing or only gasping. CPR technique should be based on the rescuer’s level of training. Rescuers are instructed to administer naloxone as soon as it is available. Rescue breathing training may be done briefly in person,53 by using a 30-second video,54 or by including a hardcopy set of instructions.55 An alternative to including training on resuscitative measures is to encourage overdose responders to follow dispatcher instructions after they have called 911 for help.

The order of action for layperson response to an opioid overdose had been to deliver rescue breathing prior to naloxone administration, as opioid-induced respiratory depression may be treated with oxygen alone, but many programs are now moving toward delivering naloxone as the first action before resuscitative measures. Other programs instruct that the first action should be to call 911 or give naloxone, whichever the responder can do the most quickly. These changes are based on program data and feedback from overdose rescuers. Both newly approved naloxone products designed for laypeople have patient information materials that instruct to administer naloxone as early as possible.

Naloxone kits, product considerations, and educational materials

As of January 2016, five different companies manufacture eight available naloxone products. All products have a shelf life of approximately 12–24 months from the date of manufacture. One product is not recommended for laypeople or take-home naloxone use because it is very complicated to assemble, and there have been several reports of failed assembly in the field during overdose emergencies (Naloxone Hydrochloride Injection, USP, 0.4 mg/mL Carpuject™ Luer Lock Glass Syringe (no needle) NDC# 0409-1782-69 by Hospira). Pharmacies should not stock the Carpuject™ naloxone product for dispensing to laypeople.

The chart below created by Prescribe to Prevent compares various naloxone product characteristics:

|

|

Auto-injector branded (Evzio Auto-Injector) |

Intranasal branded (Narcan Nasal Spray) |

Injectable generic2 |

Injectable generic |

Injectable (also off label nasal) generic1 |

| Manufacturer |

kaléo |

Adapt Pharma |

Hospira |

Mylan |

Amphastar (Teleflex-nasal adapter) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| FDA approved |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X (for IV, IM, SC; should only be used IN if approved nasal product is not feasible or available) |

| Labeling includes instructions for layperson use |

X |

X |

|

|

|

| Layperson experience |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

| Assembly required |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

| Fragile |

|

|

|

|

X |

| Can titrate dose |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

| Strength |

0.4 mg/0.4mL |

4 mg/0.1 mL |

0.4 mg/mL OR 4 mg/10 mL |

0.4 mg/mL |

1 mg/mL |

| Total volume of kit/package |

0.8 mg/0.8 mL |

8 mg/ 0.2 mL |

0.8 mg/2 mL OR 4 mg/10 mL |

0.8 mg/2 mL |

4 mg/4 mL |

| Storage requirements (store all protect away from light) |

Store at 59–77 °F

Excursions from 39–104 °F |

Store at 59–77 °F

Excursions from 39–104 °F |

Store at 68–77 °F

Breakable: Glass |

Store at 68–77 °F

Breakable: Glass |

Store at 59–86 °F

Fragile: Glass |

| Cost/kit3 |

$$$4 |

$$ |

$ |

$ |

$$ |

1IMS/Amphastar has an additional naloxone product, which has not been used in the US for layperson and take-home naloxone use. (Naloxone HCl Injection, USP, 2mg/2mL Min-I-Jet Prefilled syringe with 21 Gauge and 1 ½" fixed Needle NDC # 76329-1469-1 (10 pack) and 76329-1469-5 (25 pack)

2Hospira has an additional naloxone product, which is not recommended for layperson and take-home naloxone use because it is complicated to assemble. ( Naloxone Hydrochloride Injection, USP, 0.4 mg/mL Carpuject™ Luer Lock Glass Syringe (no needle) NDC# 0409-1782-69)

3Prices vary considerably for each product. Local pharmacists can provide specific local pricing.

4Product and co-pay coupons are available at the manufacturer's website.

Note: IV = intravenous administration, IM = intramuscular administration, SC = subcutaneous administration |

The nasally administered naloxone product, Narcan Nasal Spray, from Adapt Pharma was FDA approved in November 2015 and became publicly available in February, 2016. The 2mg/2mL naloxone product produced by Amphastar is FDA approved for IM, IV, and SC administration and has been used intranasally by first responders since the early 2000s. Because intranasal naloxone was the first line treatment for opioid overdose among emergency medical personnel in local communities in 2006, an OEND program began distributing this form of naloxone alongside a nasal adapter to laypeople.56 Since then, numerous additional OEND programs and pharmacies have begun using this product.35 However, the Amphastar product is not approved by the FDA for nasal administration; this improvised nasal product should only be used when the FDA approved nasal product is not feasible or available.

Only the brand name products are packaged as complete kits that include written instructions. All other products must be compounded by pharmacists or others who assemble the kits for distribution by other means. Regardless of the naloxone formulation, a complete naloxone rescue kit should have a minimum of two doses of naloxone, two delivery devices, and instructions. The kit components can be placed in a pharmacy bag with other medications, or they can be packaged in a special naloxone rescue kit bag. Collaboration with a local organization engaged in an overdose prevention initiative may provide special bags or containers to promote a uniform message to the community.

Examples of compounded naloxone kits are presented below:

The chart below shows that the specific prescribing information varies for each product:

| |

Auto-injector branded (Evzio Auto-Injector) |

Intranasal branded (Narcan Nasal Spray) |

Injectable generic |

Injectable generic |

Injectable (also off label nasal) generic1 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Prescription variation |

| Rx and quantity |

#1 two-pack of two 0.4 mg/0.4 mL prefilled auto-injector devices |

#1 two-pack of two 4 mg/0.1 mL intranasal devices |

#2 single-use 1 mL vials or #1 10mL multidose fliptop vial PLUS #2 3 mL syringe with 23–25 gauge 1–1.5 inch IM needles |

#2 single-use 1 ml vials PLUS #2 3 mL syringe with 23-25 gauge 1–1.5 inch IM needles |

#2 2 mL Luer-Jet Luer-Lock needleless syringe plus #2 mucosal atomizer devices (MAD-300) |

| Sig. (for suspected opioid overdose) |

Inject into outer thigh as directed by English voice-prompt system. Place black side firmly on outer thigh, depress, and hold for 5 seconds. Repeat with second device in 2–3 minutes if no or minimal response. |

Spray 0.1 mL into one nostril. Repeat with second device into other nostril after 2–3 minutes if no or minimal response. |

Inject 1 mL in shoulder or thigh. Repeat after 2–3 minutes if no or minimal response. |

Inject 1 mL in shoulder or thigh. Repeat after 2–3 minutes if no or minimal response. |

Spray 1 ml (1/2 of syringe) into each nostril. Repeat after 2–3 minutes if no or minimal response. |

| Refills |

Two |

Two |

Two |

Two |

Two |

| 1This product is FDA approved for IV, IM & SC routes of administration and should only be used IN if approved nasal product is not feasible or available Note: IV = intravenous administration, IM = intramuscular administration, SC = subcutaneous administration |

Numerous educational materials for naloxone rescue kits have been successfully field tested. Experienced providers tend to prefer short, concise materials that have images. For example, a set of instructions for one of the kits in the photos above is provided on a small foldable card, and another kit provides a sticker with illustrated instructions on the outside of the compounded naloxone kit. In addition, several short instructional videos are available on the Web. A list of resources at the end of this document provides links to these websites.

Naloxone legal and regulatory environment

Prescribing naloxone to prescription, nonmedical, or illicit opioid users is fully consistent with state and federal laws regulating drug prescribing.57 Naloxone is not a controlled substance and is regulated the same as other non-controlled prescription medicines. The risk of liability for prescribing naloxone is not higher than the risk of prescribing or dispensing other medications. Naloxone is a relatively safe medication that is associated with fewer risks than other commonly used injectable rescue medications such as epinephrine for anaphylactic shock and glucagon for hypoglycemia. We are aware of no case in which a provider and/or dispenser of naloxone has been subjected to a malpractice case or professional discipline. However, some states have passed laws to increase access and limit liability to encourage use of naloxone in outpatient and community pharmacy settings.

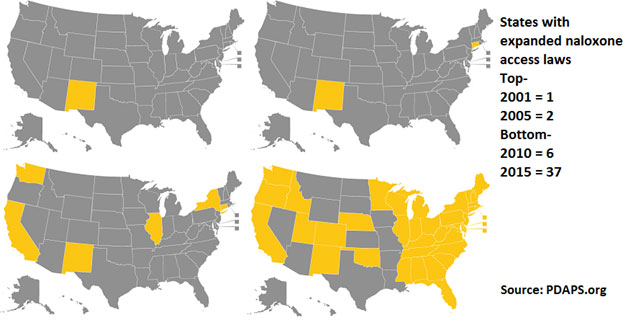

New Mexico passed the first naloxone access law passed in 2001. Very few legal changes occurred for nearly a decade after that, but the 5 years between 2010 and 2015 saw a dramatic increase in naloxone access legal changes. By the end of 2010, only six states had naloxone access laws. By September 15, 2015, all but seven states (AZ, IA, KS, MO, MT, SD, and WY) had passed legislation to improve naloxone access to laypeople!58 As of September 2015, 38 states have language supporting third-party prescribing, 29 states explicitly allow for naloxone distribution via standing orders, 38 states allow for someone to come to a pharmacy “off the street” to receive naloxone, and 30 states have specific additional liability immunity provisions for dispensers.59

The pace of change for naloxone-related legislative and regulatory change is rapid. The Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System (PDAPS.org) provides the most current language being used in jurisdictions.58

|

States have introduced innovative and collaborative pharmacy practice agreements, standing orders for naloxone dispensing by pharmacists, naloxone provision per pharmacy and/or medicine board protocol, and pharmacist as prescriber mechanisms.35 From the perspective of the consumer, this essentially means that naloxone is a “behind the counter” medicine. “Behind the counter” is in quotation marks because this is not technically correct, but it is the de facto experience for patients: they walk into a pharmacy without having seen a prescriber and walk out with naloxone. The mechanism making this possible varies by state, and the specific language is important. As of September 2015, 12 states and the District of Columbia59 do not have a mechanism in place for “behind the counter” naloxone, so there is a great opportunity for pharmacists to shape the overdose prevention initiatives being introduced in their state legislatures or to introduce them via pharmacy organizations, associations, and schools and colleges of pharmacy.

Conclusion

Pharmacists can have a significant impact on the opioid overdose public health crisis in several important ways. By continuing to provide essential education about opioids, additive drug–drug interactions, overdose recognition and response, and increasing naloxone access, pharmacists may be able to reduce the risk of fatal and nonfatal overdoses among their patients and in their communities. Pharmacist advocates can promote legislative and/or regulatory changes to increase the ability of pharmacists to provide OEND as a reimbursable service or as part of newer models of healthcare delivery such as accountable care organizations.

REFERENCES

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50):1378–1382. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm64e1218.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2016.

- American Pharmacist Association. Report of the 2015 APhA House of Delegates. J AM Pharm Association. 2015;(55):364–379.

- American Public Health Association. Preventing Overdose Through Education and Naloxone Distribution. Policy Number 20133 Statement LB-12-02. November 5, 2013. http://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/16/13/08/reducing-opioid-overdose-through-education-and-naloxone-distribution. Accessed January 10, 2016.

- Hoven AD. AMA Statement on Naloxone Product Approval. April 7, 2014. http://www.ama-assn.org//ama/pub/news/news/2014/2014-04-07-naxolene-product-approval.page. Accessed January 10, 2016.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Use of Naloxone for Prevention of Drug Overdose Deaths. April 15, 2010; rev. August 16, 2014. http://www.asam.org/advocacy/find-a-policy-statement/view-policy-statement/public-policy-statements/2014/08/28/use-of-naloxone-for-the-prevention-of-drug-overdose-deaths. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. NABP Issues Policy Statement Supporting the Pharmacist's Role in Increasing Access to Opioid Overdose Reversal Drug. October 20, 2014. https://www.nabp.net/news/nabp-issues-policy-statement-supporting-the-pharmacist-s-role-in-increasing-access-to-opioid-overdose-reversal-drug. Accessed January 10, 2016.

- Doyon S, Aks SE, Schaeffer S. Expanding access to naloxone in the United States. Clin Toxicol. 2014;52:989–992.

- Bailey AM, Wermeling DP. Naloxone for opioid overdose prevention: pharmacists' role in community-based practice settings. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(5):601–606. doi:10.1177/1060028014523730.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit. 2014. http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Opioid-Overdose-Prevention-Toolkit-Updated-2014/SMA14-4742. Accessed January 10, 2016.

- National Institutes of Health. Pathways to Prevention Workshop: The Role of Opioids in the Treatment of Chronic Pain, September 29–30, 2014. https://prevention.nih.gov/docs/programs/p2p/ODPPainPanelStatementFinal_10-02-14.pdf Accessed January 10, 2016.

- Volkow ND. Harnessing the Power of Science to Inform Substance Abuse and Addiction Policy and Practice. 2014. http://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2015/harnessing-power-science-to-inform-substance-abuse-addiction-policy-practice. Accessed January 10, 2016.

- San Francisco Department of Public Health. Opioid Safety and How to Use Naloxone: A Guide for Patients and Caregivers. 2014. http://prescribetoprevent.org/wp2015/wp-content/uploads/CA.Detailing_Patient_final.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2016.

- Park H, Bloch M. How the epidemic of drug overdose deaths ripples across America. New York Times. January 19, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/01/07/us/drug-overdose-deaths-in-the-us.html?_r=0. Accessed January 21, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NCHD Data Visualization Pilot. Drug Poisoning Mortality: United States, 2002–2014. January 19, 2016. http://blogs.cdc.gov/nchs-data-visualization/drug-poisoning-mortality/. Accessed January 21, 2016.

- Cicero T, Ellis M, Surratt H, Kurtz S. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 Years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(7),821–826.

- Prescribe To Prevent. Primary, Chronic Pain and Palliative Care Setting: 2015. http://prescribetoprevent.org/prescribers/palliative/ Accessed January 10, 2016.

- American Geriatrics Society Panel. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2009;57,1331–1346.

- Narcan nasal spray [full prescribing information]. Radnor, PA: Adapt Pharma, Inc: 2015. http://narcannasalspray.com/pdf/NARCAN-PI.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Evzio auto-injector [full prescribing information]. Richmond, VA. Kaléo, Inc: 2014. http://evzio.com/pdfs/Evzio%20PI.PDF. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Naloxone [package insert]. Lake Forest, IL: Hospira Inc: 2008.

- Clarke SF, Dargan PL, Jones Al. Naloxone in opioid poisoning: walking the tightrope. Emerg Med J. 2005;22(9):612–616.

- Longnecker DE, Grazis PA, Eggers GWN. Naloxone for antagonism of morphine-induced respiratory depression. Anesth Analg.1973;52:447–452.

- Chiang WK, Goldfrank LR. Substance withdrawal. Emerg Clin North Am.1990;8:613–632.

- Schwartz JA, Koenigsberg MD. Naloxone-induced pulmonary edema. Ann Emerg Med.1987;16:1294–1296.

- Gopinathan K, Saroja D, Spears JR, et al. Hemodynamic studies in heroin induced acute pulmonary edema. Circulation. 1970;42(supplement):44.

- Duberstein JL, Kaufman DM. A clinical study of an epidemic of heroin intoxication and heroin-induced pulmonary edema. Am J Med.1971;51:704–714.

- Mariani PJ. Seizure associated with low-dose naloxone (letter). Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7:127–128.

- Michaelis LL, Clark TA, Dixon WM. Ventricular irritability associated with the use of naloxone hydrochloride. Ann Thorac Surg.1974;18:608–614.

- Merigian KS. Cocaine-induced ventricular arrhythmias and rapid atrial fibrillation temporally related to naloxone administration. Am J Emerg Med.1993;11:96–97.

- Azar I, Turndorf H. Severe hypertension and multiple atrial premature contractions following naloxone administration. Anesth Analg.1979;58:524–525.

- Sporer KA, Firestone J, Isaacs M. Out-of-hospital treatment of opioid overdoses in an urban setting. Acad Emerg Med.1996;3:660–667.

- Walley AY. Evaluating the Impact of Overdose Prevention Education and Naloxone Rescue Kits in Massachusetts. Presented at Exploring Naloxone Uptake and Use: Measuring Progress and Impact. 2015. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/NewsEvents/UCM454823.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Green TC, Dauria EF, Bratberg J, Davis, CS, Walley, AY. Orienting patients to greater opioid safety: models of community pharmacy-based naloxone. Harm Reduct. J. 2015;12, 25.

- Maxwell S, Bigg D, Stanczykiewicz K, Carlberg-Racich S. Prescribing naloxone to actively injecting heroin users: a program to reduce heroin overdose deaths. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(3):89–96.

- Wheeler E, Jones T, Gilbert M, Davidson P. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(23):631–635.

- Walley AY, Ziming X, Hackman H, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

- Bird SM, McAuley A, Perry S, Hunter C. Effectiveness of Scotland's national naloxone programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: a before (2006-10) versus after (2011-13) comparison. Addiction. 2015. doi:10.1111/add.13265. [Epub ahead of print]

- Rowe C, Santos G-M, Behar E, Coffin PO. Correlates of overdose risk perception among illicit opioid users. Drug Alcohol Dep. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.018. [Epub ahead of print]

- San Francisco Department of Public Health. Naloxone for Opioid Safety: A Provider's Guide to Prescribing Naloxone to Patients Who Use Opioids. 2014. http://prescribetoprevent.org/wp2015/wp-content/uploads/CA.Detailing_Provider_final.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2016.

- Gwira Baumblatt JA, Wiedeman C, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, Paulozzi LJ, Jones TF. High-risk use by patients prescribed opioids for pain and its role in overdose deaths. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:796–801.

- Yang Z, Wilsey B, Bohm M, et al. Defining risk of prescription opioid overdose: pharmacy shopping and overlapping prescriptions among long-term opioid users in Medicaid. J Pain. 2015;16:445–453.

- Walley AY, Doe-Simkins M, Quinn E, et al. Opioid overdose prevention with intranasal naloxone among people who take methadone. J Sub Abuse Treatment. 2013;44(2):241–247. doi:org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.07.004

- University of Wyoming. Medication Disposal Day. http://www.uwyo.edu/pharmacy/news/2012/09/medication-disposal-day.html. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Duquesne University. DEA National Drug Take Back Day. http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/pharmacy/pharmacy-events/dea-national-drug-take-back-day. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. Students, Faculty from School of Pharmacy Participate in Drug Take-Back Day.http://lecom.edu/students-faculty-from-school-of-pharmacy-participate-in-drug-take-back-day/. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- University of Missouri-Kansas City. UMKC School of Pharmacy Plays Major Role in National Drug Take Back Day. http://pharmacy.umkc.edu/umkc-school-of-pharmacy-plays-major-role-in-national-drug-take-back-day/. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Drug Enforcement Agency, Office of Diversion Control. National Take-Back Initiative. http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/takeback/. Accessed January 10, 2016.

- Food and Drug Administration. Medicines Recommended for Disposal by Flushing. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/UCM337803.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Rhode Island Department of Health. If You Let Her Sleep It Off Poster. http://prescribetoprevent.org/wp-content/uploads/OD_Poster_ENG_Female_RI.pdf Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Scottish Drugs Forum. I Saved My Son's Life Poster. http://www.sdf.org.uk/drug-related-deaths/new-naloxone-training-and-promotional-materials-2013/. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Community Management of Opioid Overdose. 2014;12–14. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/management_opioid_overdose/en/. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Lavonas EJ, Drennan IR, Gabrielli, A, et al. 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, Part 10: Special Circumstances of Resuscitation, Circulation. 2015. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/132/18_suppl_2/S501.full Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Behar E, Santos GM, Wheeler E, Rowe C, Coffin PO. Brief overdose education is sufficient for naloxone distribution to opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:209–212.

- Breathe video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-xDD-Lj30Ns Accessed January 12, 2016.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Opioid Overdose Resuscitation Palm Card. http://prescribetoprevent.org/wp-content/uploads/Opioid-Overdose-Card-Am-Soc-Anesthesiologists.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Doe-Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, Moyer P. Saved by the nose: bystander-administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:788–791.

- Burris S, Norland J, Edlin B. Legal aspects of providing naloxone to heroin users in the United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2001;12(3):237–248.

- Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System. Naloxone Overdose Prevention Laws. http://www.pdaps.org/dataset/overview/laws-regulating-administration-of-naloxone/56d0ccbfd42e0764402b2f82. Accessed April 2, 2016.

- Davis CS, Carr D. Legal changes to increase access to naloxone for opioid overdose reversal in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;157:112–120.

Resources for pharmacists

- SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit equips communities and local governments with material to develop policies and practices to help prevent opioid-related overdoses and deaths.

- PrescribeToPrevent.orgcontains resources directed toward healthcare providers such as doctors, nurses, and pharmacists who are interested in prescribing naloxone to patients. This unfunded and volunteer-run site contains many options for patient education materials.

- The College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists has developed Naloxone Access: A Practical Guideline for Pharmacists to increase naloxone access.

- The Chicago Recovery Alliancestarted the first organized overdose project in the United States in 1996 and has downloadable information resources. Some of the most realistic video training materials are available at this site, in particular LIVE! from Sawbuck Productions.

- The Harm Reduction Coalition has operated overdose prevention programs in San Francisco and New York City for many years. The site includes the Guide to Developing and Managing Overdose Prevention and Take-Home Naloxone Projects; this is the best resource of its kind and a must-have reference for anyone doing overdose work. The coalition also has a large collection of training and advocacy videos.

- Law Atlas contains options for state-by-state naloxone overdose prevention and a list of 911 Good Samaritan overdose prevention laws.

- The Overdose Prevention Alliance has a monthly curated list of pertinent research, as well as a national community-based naloxone program locator.

- Reach for Medocuments effects of naloxone pricing, production shortages, and inconsistent funding. The website also includes interviews and advocacy materials, including Facebook cover images, avatars, and downloadable, shareable posters.

- Staying Alive on the Outside is the first overdose prevention training video that specifically targets those being released from prison. This award-winning production is from the Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights at Brown University.

Back to Top