Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Module 14. Assessing and Optimizing Patient Adherence in MTM

Overview: Assessing Adherence in MTM

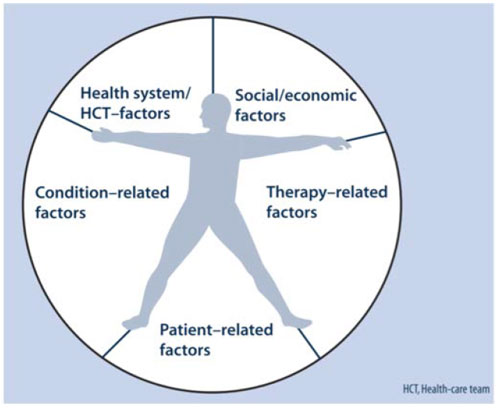

Assessing patient adherence to therapy and promoting better adherence are among the chief goals of any MTM consultation. Even an ideal drug regimen becomes useless, and costly, if the patient will not use the medication. Managing adherence has become more challenging in today's healthcare environment. The variety and complexity of therapeutic options continues to expand for many medical conditions, and a greater number of patients are prescribed multiple medications. For the pharmacist conducting MTM, addressing adherence is a broad issue that must balance the goals of effective disease management, safety and tolerability, and patient lifestyle factors. The multiple factors involved in adherence were diagrammed in a World Health Organization (WHO) report (Figure 1).1

Figure 1. Five Dimensions of Adherence1

Reprinted with permission from: World Health Organization.

Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action.

Available at: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/

During MTM, the goal is not for pharmacists and APRNs to simply remind patients to take their medications. MTM may involve adjusting a medication regimen to fit better with that person's lifestyle, determining whether any necessary safety monitoring is needed, and helping the patient understand and adjust to the effects of a drug therapy. The term "adherence" is preferred over "compliance," because it connotes patient cooperation and buy-in for the overall therapeutic regimen, rather than obedience to the healthcare provider.2

Prevalence of Nonadherence

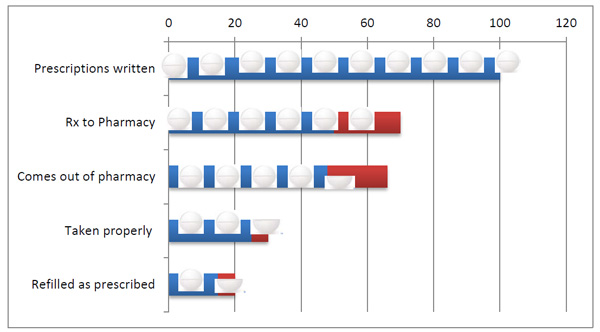

Americans are a "medication-taking society."3 Four out of 5 Americans take at least one medication every week, and one-third of Americans take at least 3 medications every week.3 In developed countries, adherence to therapy for any chronic disease is estimated at approximately 50%.4 Studies comparing patient self-reports to findings from electronic dose monitoring systems suggest that at least 80% of patients over-report their adherence.5 The reality of how many prescriptions actually are taken as directed is illustrated in Figure 2.6

Figure 2. Gap between written prescription and medication use

For every 100 prescriptions written, only 15 to 20 are refilled as prescribed

Source: National Association of Chain Drug Stores.

Pharmacies: Improving Health, Reducing Costs. July 2010, based on IMH Health data.6

Impact of Nonadherence on Care Outcomes

Failure to use medications as directed has been described as the "single greatest detractor to efficacy" for many people with chronic illness. Undetected, nonadherence often leads to:

- Unnecessary switching and/or escalation of therapy,

- Increases visits to physicians and hospitals; hospital admissions

- Increases costs of therapy, drug waste

Nonadherence accounts for 30% to 50% of all treatment failures.7 When a patient has an inadequate response to a medical therapy, many practitioners either adjust the dose of the agent if possible, or switch patients to a different drug in an effort to gain better control of the disease. The WHO report, Adherence to Medical Therapy: Evidence for Action, points out that "Increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments."1

Predictors of Adherence to Medications

Dozens of studies have been conducted to analyze why patients are nonadherent to medical therapies and to detect what factors are associated with improvements in medicine-taking behaviors. The specific reasons may differ by disease type and other variables, but there are certain common issues that can be considered.8-16

Factors that positively influence adherence

- Patient is better informed about the disease

- Patient believes in the need for therapy

- Increased dosing convenience: simplified regimens, shorter duration of therapy, lower pill burden (e.g., combination tablets)

- Lower co-payments

Factors that negatively influence adherence

- Patients do not believe their condition requires treatment

- Patients believe disease is "too advanced" to respond to medication therapy

- Depression, alcohol/substance use

- Cognitive deficits, forgetfulness

- Adverse effects, or concerns about long-term effects

- Greater pill burden

- Higher medication cost/copay

Assessing Adherence to Medications in MTM

True adherence to therapy is difficult to measure because it relies on a person's honest recounting of medication doses taken. As part of the comprehensive medication review in MTM, pharmacists and APRNs can try to gain a more realistic sense of adherence, by applying some of the following strategies:

- Avoid closed-ended questions, like: "Do you take this every day?" This calls for a one-word answer. "Yes" is easier than "no." Instead, ask, "Tell me how you are taking this."

- Do not make assumptions; avoid judgment

- Use the "show-me technique" for complicated dosage forms

- Use objective evidence, including fill history, evaluation of medications patient brings to the appointment

It's difficult even for otherwise-honest people to admit they do not take their medications. Some may feel that—given the great deal of time, effort, and money that has gone into providing this treatment—they have an obligation to adhere to therapy. At the same time, the reality of busy lifestyles, drug side effects, difficulties with administering the medication, and failure to understand dosage instructions present a compelling conflict. It may be easier for the person to say to the physician or pharmacist, "Yes, I'm using the drugs," than, "No, but I can't really explain why."

Developing a personal relationship and rapport with the patient during MTM has been shown to increase adherence in many disease states.17-19 Expressing a sense of empathy is often effective. When the pharmacist acknowledges that nonadherence is a very common problem, this admission can be a great relief to a person who has been hiding the issue. For example, if the pharmacist uses statements like, "How many days would you say you miss per week?" this opens the door for the patient to admit that some doses are missed. It invites the pharmacist to acknowledge that this is normal and to move on to possible solutions.

Tools for Measuring Medication Adherence

Measuring patient adherence and taking steps to increase adherence are increasingly used as part of quality measures in healthcare delivery. The ability to track and document adherence measures such as medication refill data will be an increasingly important aspect of quality reporting and reimbursement.

Measuring and monitoring patient adherence may become an important aspect of pharmacists' and APRNs' roles, especially as the system moves toward pay-for-performance (P4P) models. P4P models offer bonus payments to providers (including pharmacists and APRNs in some areas) when Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) measures are met among patients who receive Medicare Part D benefits. Among five PQA measures, two involve medication safety and three are adherence-based measures for: 1) oral diabetes medications, 2) cholesterol-lowering medications (statins), and 3) antihypertensives (renin–angiotensin system antagonists).

Ensuring that these adherence measures are met requires engagement with both patients and prescribing physicians. Some of the tools used to quantify adherence include medication possession ratio (MPR) and proportion of days covered (PDC), as explained below.

Medication Possession Ratio (MPR)

MPR =

Number of days the medication was supplied within a refill period

Number of days in the refill period

MPR can overestimate adherence, because the ratio will be artificially high for patients who routinely refill their medications early. In addition, "medication possession" does not reveal information about whether patients have actually taken the medication; only whether they refill the prescription.

Proportion of Days Covered (PDC)

PDC =

Total days of all drugs available

Number of days in that period

Using this measure, if a patient refills 5 days early, those days are added on to the next period. PDC provides a more conservative estimate of medication adherence relative to MPR, especially when multiple medications are used.

Medication Fill Data

This is not a reliable measure of adherence, because not all medications are filled in one place.

Addressing Specific Adherence Issues in MTM

Once the conversation has been started, the pharmacist should attempt to identify any potential barriers that affect that individual. Addressing adherence problems during MTM is challenging and highly patient-specific.16 Some common barriers and proposed pharmacist interventions are outlined in Table 1.

| Table 1. Common Barriers to Adherence and Proposed Interventions |

| Barriers |

Pharmacist interventions |

|

Forgetfulness

Fear of long-term effects

Adverse effects

Unclear about instructions

Perceived lack of efficacy

Cost

|

Reminder systems tailored to patient's lifestyle and preferences

Discuss risk-benefit analysis of therapy

Manage when possible; suggest change in therapy if needed

Address questions; refer questions to prescriber when necessary

Explain to patient why the medication is being taken; discuss expectations, impact on symptoms, how the drug works.

Recommend lower cost alternatives, generic programs, patient or co- pay assistance programs

|

Forgetfulness

Forgetfulness is one of most commonly cited reasons for nonadherence. Adherence rates tend to drop when a medication regimen is more complex and increase when a regimen is simplified.20 When a patient says, "I just keep forgetting," he or she may be masking another underlying problem, such as fear of adverse effects. Remedies for forgetfulness include tools such as dose-dispenser systems, electronic reminders, and even smartphone technologies.

Perceived lack of efficacy ("I really don't need this drug" or "It's not working for me")

Perceived lack of efficacy is one of the most commonly cited reasons by patients for missing doses and for discontinuing therapy.9,21 People may not "feel" the effects of the disease they are treating (a classic example is hypertension), and may not necessarily notice beneficial effects on their health when they take the agent properly. Unrealistic expectations of drug therapies has been shown to be highly predictive of premature discontinuation.22

Difficult medication regimen (e.g., injectable administration)

Difficult regimens may include injectable or inhaled therapies. Fear of self-injection has been reported as a significant reason for nonadherence for many patients, particularly those using these therapies over a long-term period for diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, or multiple sclerosis. Even a patch can be a complex regimen for some patients, if it involves site rotation or remembering to remove the patch at a certain time.

It may seem that the relative ease of taking a pill would overcome most adherence problems. However, adherence to oral therapies by people with chronic health conditions is low and tends to decrease with time.1 Even when an oral drug has the potential to noticeably reduce symptoms or would yield nearly 100% efficacy (such as with oral contraceptives), adherence tends to be low.23

Early discontinuation from therapy

Prescription "abandonment" is a common occurrence, particularly during care transitions such as discharge from a hospital and for drugs with higher copay amounts.24 Data from multiple studies show that people who discontinue treatment tend to do so within the first 12 months of therapy.25 Adverse effects are high on the list given by both patients and physicians as reasons for stopping therapy. If the patient discontinues due to adverse effects, this tends to occur soon after treatment initiation. Usually patients who discontinue therapy for any reason do so without seeking medical advice.

Reasons for early discontinuation include:

- Assumed lack of therapeutic efficacy

- Lack of conviction that therapy influences the disease

- Intolerable side effects

- Inconvenience of regimen/poor fit with lifestyle

- Fear of bringing disease or health condition to mind regularly

- Doubt about the diagnosis

- Inability to afford initial therapy or continued therapy

|

Patient Case #1. Adherence to a Daily Oral Medication

Laura J., a 42-year-old mother of 3 young children, had radioactive iodine therapy for hyperthyroidism approximately 5 years ago, and has had variable adherence to her daily oral levothyroxine (T4) replacement therapy over the years. After appointments with her endocrinologist, her adherence level is high, but it tends to drop after a few months as she gets "too busy" to remember to take her pill every day. The MTM pharmacist notes from her chart that she has become significantly hypothyroid at times, with detrimental effects on her life and health. Mrs. J. knows that her thyroid replacement therapy is important, but just can't seem to make it part of her routine.

Instead of simply telling the patient that it is important to take the medication daily (which her physician has done), the pharmacist needs to determine her specific barriers to adherence.

Pharmacist: "Tell me about some of the issues that you think prevent you from using this medicine regularly."

Patient: "Well, my doctor has told me I always have to take it first thing in the morning, on an empty stomach, and then wait 30 minutes. But sometimes I forget and don't think about it until I sit down for breakfast."

Pharmacist: "How many doses would you say you forget each week?"

Patient: "Maybe one, two times a week at most."

Pharmacist: "What do you do when you realize you forgot? Do you take the pill later in the day, or with your breakfast?"

Patient: "No—my doctor said it won't work as well with meals, so I usually just skip it that day."

Forgetfulness is a major cause of nonadherence, for people with impaired memory but also for those with unpredictable schedules, such as parents of young children. In addition, the patient seemed to have some confusion about the role of food intake and drug absorption.

Pharmacist: "Let's talk about ways you can make this more a part of your daily routine. First of all, have you considered taking the pills at night?"

Patient: (Laughs) "My nighttime routine is even crazier than the morning!"

Pharmacist: "Okay. So let's go back to mornings. Is there anything you do consistently every morning, say, first thing?"

Patient: "Well, I have to have my coffee to function. I actually make it the night before and just press the button to start it brewing."

Pharmacist: "Do you wait a bit before eating some breakfast?"

Patient: "Yes, after my kids have gotten on the school bus."

Pharmacist: "Let's try something new: Can you make a promise to yourself that you will take your pill with a glass of water right when you wake up, and you will not allow yourself to start brewing the coffee until the pill is taken?"

Patient: "How long would I have to wait to drink my coffee?

Pharmacist: Studies show that it's probably okay to have coffee soon after your thyroid pill, but delaying it by about 30 minutes would be better.1 Hydrating yourself with a bit more water in the morning is always good, and you can enjoy your hot coffee after the kids are on the bus. Also, I'd like to encourage you to start using a pill organizer case so you know how many doses you have taken each week. Be sure to adapt your system for your schedule on weekends. Try to go two weeks without missing a single dose, and then give yourself a small reward."

Patient: "Like...gourmet coffee from a coffee bar?"

Pharmacist: "Yes! You can also try setting an alarm on your smartphone to ring every day, right around the time you plan to take the pill, as an added reminder."

Patient (has smartphone in hand): "I can definitely do that."

The pharmacist has offered 3 solutions that are easy to implement and fit well with the patient's lifestyle. The pharmacist has also suggested a short-term goal for the patient. Next the pharmacist addresses a longer-term goal and follow-up plan.

Pharmacist: "Let's set a goal of 3 months of consistently taking your medication. Then we'll arrange to have your blood drawn again to see how the medication is affecting your thyroid hormone levels."

Patient: "They always give me a lab request sheet but sometimes I lose track of it."

Pharmacist: "We can set up a reminder system to get in touch with you in 3 months. From there, I can work with you and your doctor to get the right paperwork and set the lab appointment. Let's also make sure you have a 3-month supply of your medication now. We'll find out after the blood test if the dose should be changed."

Because the patient has young children, the pharmacist asks the patient about storage of her medications, and suggests a convenient cupboard lock sold at the pharmacy to ensure safe storage of the medication.

1. Liwanpo L, Hershman JM. Conditions and drugs interfering with thyroxine absorption. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23(6):781-792.

|

Motivational Tips to Achieve Change in Adherence Behaviors

Pharmacists are regarded as the health professionals with the greatest degree of knowledge and expertise when it comes to addressing adherence issues. However, it is unrealistic to expect that one MTM encounter is going to change a person's long-term behavior patterns. The MTM pharmacist can utilize the "Contemplation Ladder" to determine the patient's degree of motivation for improving adherence (Figure 3).26

| Figure 3. The Contemplation Ladder for Changing Adherence Behavior26 |

|

|

Maintenance:

"I have been doing so much better at taking my blood

pressure medicines."

Action:

"I have recently started to take my medicines more regularly."

Preparation:

"I have taken steps to help me remember my daily dose of blood pressure medicine."

Contemplation:

"I know I really need to do better at taking my medications."

Precontemplation:

"I don't know why I need all of these medicines." |

According to experts in behavior change and motivational interviewing, some of the same techniques are applied at all stages of readiness to change. These are summarized in the GRACE method, explained in Table 2.27,28

| Table 2. GRACE Acronym for Motivational Interviewing |

|

Generate a gap

Generate a gap between what the patient wants and the reality, rather than imposing an external reason for change.

Roll with resistance

Ambivalence should be viewed as normal. Explored reasons for ambivalence openly, rather than denying them.

Avoid arguments

Arguments increase resistance to change. The pharmacist should instead try to get the patient to express the need for change.

Can do

The pharmacist should encourage self-efficacy and hope for success

Express empathy

Listen, communicate, and support

|

Tips for Counseling Patients About Adherence

1. Learn the patient's belief set

Does the patient understand significance of his/her condition?

Is the person motivated to take any medication for the condition?

Does patient believe pros of taking medication outweigh the cons?

Has patient lost motivation to treat the disease (e.g., he/she is feeling good,

he/she doesn't believe the medication is helping)?

2. Inquire about goals

Is there anything the disease is preventing that the patient would like to do again?

3. Become familiar with family history, priorities, and cultural beliefs

Is the person motivated to remain healthy for a child or other family member?

Does the person have a family member whose condition worsened because of failure

to take a medication?

4. Give the patient a sense of collaboration into decision-making process

Work together to select a medication that the person will have a genuine "interest" in taking

Maintain independence for a longer time

Reduce the risk of having frequent relapses

5. Learn the patient's attitudes about taking medications in general

Past negative experiences

Patterns of taking medications in the past; schedules that work best

6. Understand the patient's reimbursement status

High copayments

Fixed income

Qualified for special programs (Low income subsidy if Part D)

Impact of Low Literacy and Health Literacy on Medication Adherence

The Institute of Medicine report, "To Err is Human," describes a case in which a 66-year old man discharged from the hospital following atrial fibrillation was later rushed to the ER due to an overdose of warfarin.29 The man had ignored his doctor's verbal orders and written discharge instructions, and had failed to follow up with a physician post-discharge. In this case, the problem was not that the man didn't care about his health—he simply could not read and did not want to admit this fact to the doctor. The documents were essentially useless pieces of paper to him, and the verbal instructions were either forgotten or misunderstood.29

Many people who have low literacy are skillful at hiding this fact from healthcare providers because they are too ashamed to admit they do not read well (or do not read at all), or that they do not understand the information that was provided verbally. According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), about 14% of Americans have a literacy level "below basic prose," meaning that they can understand only simple, straightforward content from a short piece of text.30 Generally speaking, this would rule out most medication information or instructions. The NAAL further reports that approximately 22% have below basic quantitative literacy (understanding only simple numeric concepts; unlikely to understand numbers embedded in printed materials).30

There are many excellent tools available to pharmacists and APRNs to assess written literacy and health literacy. Some of the best-validated screening tools include the REALM-SF (Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine–Short Form) and the SILS (Single-item Literacy Screener).31,32 Organizations such as the NAAL and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) provide guidelines and tools for evaluating literacy and health literacy in the pharmacy. In keeping with the overall philosophy of MTM, it is important to avoid belittling patients or making them feel ashamed about poor or nonexistent reading skills. A set of health pictograms is available for free download from the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention.33 Use of these pictograms by health professionals has been shown to improve adherence to medications.34

Health literacy can be an entirely different concept compared with prose or quantitative (number) literacy. Even a highly educated and literate person may have very low health literacy. Many drug names sound the same, similar drug names are frequently confused, and many consumers have little ability to distinguish between brand names and generic names of the agents they are using. Evaluating and addressing a patient's health literacy are important in the process of MTM. The AHRQ's Health Literacy Toolkit includes a number of useful resources toward this goal, including:35

- Pharmacy Health Literacy Assessment Tool and User's Guide

- Training Program for Pharmacy Staff on Communication

- Guide on How to Create a Pill Card

- Telephone Reminder Tool to Help Refill Medicines on Time

Summary and Conclusions

One of the basic tenets of adherence is that a person's perceived need for a medication must outweigh the downsides, such as inconvenience, cost, and possible adverse effects.36 This is truer now than ever before, with a greater variety of therapies available and a greater need to balance the risks and benefits of drug therapies. Pharmacists and APRNs must be aware of the importance of adherence in making therapeutic decisions, considering safety risks, and evaluating the potential efficacy of an agent.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2003.

- Bell JS, Airaksinen MS, Lyles A, et al. Concordance is not synonymous with compliance or adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(5):710-711; author reply 711-713.

- Institute of Medicine. Preventing Medication Errors. 2006 Available at: http://www.nap.edu.

- Ernst FR, Grizzle AJ. Drug-related morbidity and mortality: updating the cost-of-illness model. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2001;41(2):192-199.

- Zeller A, Ramseier E, Teagtmeyer A, et al. Patients' self-reported adherence to cardiovascular medication using electronic monitors as comparators. Hypertens Res. 2008;31(11):2037-2043.

- National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Pharmacies: Improving Health, Reducing Costs. July 2010.

- Medication Adherence Time Tool: Improving Health Outcomes. 2011, American College of Preventive Medicine. Available at: http://www.acpm.org.

- Bonnerup DK, Lisby M, Eskildsen AG, et al. Medication Counselling: Physicians' Perspective. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013.

- Curkendall SM, Thomas N, Bell KF, et al. Predictors of medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(10):1275-1286.

- Egede LE, Gebregziabher M, Echols C, et al. Longitudinal effects of medication nonadherence on glycemic control. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(5):562-570.

- Goodfellow NA, Almomani BA, Hawwa AF, et al. What the newspapers say about medication adherence: a content analysis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:909.

- Jarab AS, Almrayat R, Alqudah S, et al. Predictors of non-adherence to pharmacotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014.

- Khan MU, Shah S, Hameed T. Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence among hypertensive patients attended National Health Service Hospital, Sunderland. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6(2):104-108.

- Haynes RB, Yao X, Degani A, et al. Interventions to enhance medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(4):CD000011.

- Haynes RB, McDonald HP, Garg AX. Helping patients follow prescribed treatment: clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2880-2883.

- Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, et al. Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(2):CD000011.

- Snyder ME, Zillich AJ, Primack BA, et al. Exploring successful community pharmacist-physician collaborative working relationships using mixed methods. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2010;6(4):307-323.

- Donohue JM, Huskamp HA, Wilson IB, et al. Whom do older adults trust most to provide information about prescription drugs? Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(2):105-116.

- Keshishian F, Colodny N, Boone RT. Physician-patient and pharmacist-patient communication: geriatrics' perceptions and opinions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(2):265-284.

- Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009;256(4):568-576.

- Hanlon JT, Shimp LA, Semla TP. Recent advances in geriatrics: drug-related problems in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(3):360-365.

- Juhnke C, Muhlbacher AC. Patient-centredness in integrated healthcare delivery systems - needs, expectations and priorities for organised healthcare systems. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13:e051.

- Halpern V, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Strategies to improve adherence and acceptability of hormonal methods of contraception. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;10:CD004317.

- Shrank WH, Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, et al. The epidemiology of prescriptions abandoned at the pharmacy. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(10):633-640.

- Salzman C. Medication compliance in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56 Suppl 1:18-22; discussion 23.

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: a comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addict Behav. 1982;7(2):133-142.

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527-537.

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Abuse Treatment. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 1999. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 35.) Chapter 3—Motivational Interviewing as a Counseling Style. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64964/.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, Ed. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine: Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 2014.

- National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). A nationally representative and continuing assessment of English language literacy skills of American adults. U.S. Department of Education. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/naal/kf_demographics.asp.

- Health Literacy Measurement Tools: Fact Sheet. January 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy/index.html.

- Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, et al. The Single Item Literacy Screener: evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC family practice. 2006;7:21.

- U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention. USP Pictogram Library. Available at: http://www.usp.org/usp-healthcare-professionals/related-topics-resources/usp-pictograms.

- Braich PS, Almeida DR, Hollands S, et al. Effects of pictograms in educating 3 distinct low-literacy populations on the use of postoperative cataract medication. Can J Ophthalmol. 2011;46(3):276-281.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Health Literacy Tools for Use in Pharmacies. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/pharmhealthlit/tools.html.

- Shah B, Chewning B. Conceptualizing and measuring pharmacist-patient communication: a review of published studies. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2006;2(2):153-185.

Back to Top