Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Primer on Prevention and Treatment of HIV Infection

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

continue to plague patients worldwide despite remarkable advances in antiretroviral therapies.

This is exemplified by the recent "Indiana outbreak" in that state's Scott County, which

garnered national attention after its HIV incidence increased significantly over a short period of

time.1 The Indiana outbreak, fueled by intravenous drug abuse, shows that issues beyond

access to care perpetuate HIV infection in the United States (U.S.).

The purpose of this activity is to provide an update on nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic

interventions for HIV infection and review testing-related requirements of the Florida Omnibus

AIDS Act.

Epidemiology

In 2012, an estimated 35 million people were living with HIV infection worldwide.2 Interestingly,

the global incidence decreased from 2002 to 2012, which epidemiologists believe is related to

reductions in heterosexual transmission.3 Despite efforts to test, treat, and retain patients in

care, select U.S. populations continue to be disproportionally affected, especially African

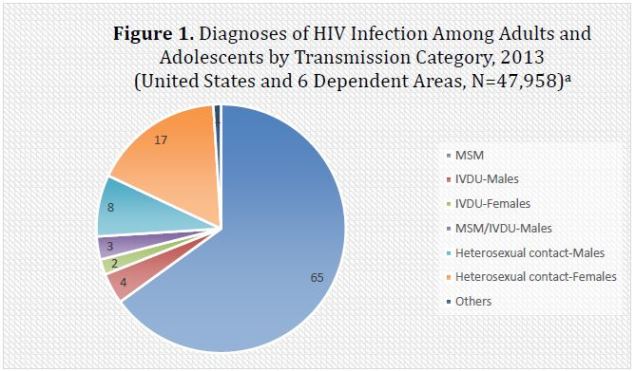

Americans and men who have sex with men (MSM).4 Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of HIV

infection diagnoses in 2013 among American adolescents and adults by method of

transmission.

| Figure 1. Diagnoses of HIV Infection Among Adults and Adolescents by Transmission Category, 2013

(United States and 6 Dependent Areas, N=47,958)a |

|

| Abbreviations: IVDU, intravenous drug user; MSM, men who have sex with men.a

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.4 |

New HIV infection diagnoses appear to be concentrated in the southeastern U.S. Data from one

epidemiologic study show that more than one-half of all newly diagnosed patients are from the

south,5 which may be the result of a complex interplay between demographic, economic, and

social networks.6,7 Further, 3 of the top 5 states with the highest rates of HIV infection per

100,000 population are located in the southeastern U.S.4: (1) District of Columbia, 109.2; (2)

Maryland, 43.7; (3) Georgia, 36.7; (4) Louisiana 36.6; and (5) Florida, 32.1. The continued

burden on those affected by HIV infection was the impetus for the National HIV/AIDS strategy

to close the chasm between patients who are diagnosed or are unaware of their HIV status and

the need for virologic suppression.

Overview of HIV Infection

HIV infection cannot be fully eradicated from the body. Available treatments focus on slowing

viral replication, which occurs rapidly in gut-associated lymphoid tissue and the central nervous

system.8,9 HIV infection's primary target is CD4 T-lymphocytes (CD4 cells). Multiple co-receptors

facilitate HIV's entry into CD4 cells, and have become pharmacologic targets in recent years: C-C

chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) and C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4).3 Viral replication

within human CD4 cells eventually leads to immune suppression, which increases the body's

susceptibility to a number of infections.

Acute HIV infection usually displays high viral replication in conjunction with a decline in CD4

cells 1 to 4 weeks after exposure. Unfortunately, HIV infection's acute clinical presentation is

similar to nonspecific viral illnesses such as mononucleosis and influenza, making diagnosis

difficult.10 Common symptoms include fever, lymphadenopathy, and maculopapular rash.

Further, HIV antibodies usually develop 4 to 6 weeks postinfection. Delayed production in HIV

antibodies is known as the "window period." As a result, diagnostic tests often are incapable of

detecting infection during this timeframe, which can result in a false-negative test result (a

result that appears negative when it should not).

After acute HIV infection, patients enter a latent stage during which HIV ribonucleic acid (RNA)

remains relatively stable and CD4 cells are gradually depleted. However, as HIV infection

progresses and a patient's immune system becomes increasingly compromised, the transition

to AIDS eventually occurs. A diagnosis of AIDS is made when a patient's clinical condition meets

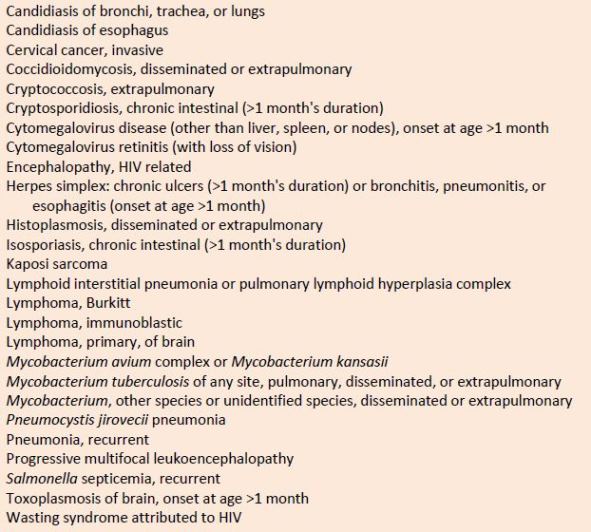

any one of the following criteria11:

- Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4 count less than 200 cells/mm3

- Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4 percentage less than 14%

- Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and any AIDS-defining condition (Table 1).

| Table 1. AIDS-Defining Conditions |

|

| Source: Reference 12 |

In clinical practice, patients frequently present with advanced disease because they were

unaware of their HIV infection status. This reinforces the importance of closing the gap

between identifying individuals who are infected and treating them with the most up-to-date

care.

Transmission

HIV infection can be transmitted through sexual contact, intravenous drug use (IVDU), contact

with select bodily fluids, vertical transmission (mother to child transmission) and, to a lesser

extent, exposure to blood products.13 Because of consistent screening practices that are in

place for blood donors and blood products, transmission after exposure to blood products has

become exceedingly rare.14 Bodily fluids that pose a high transmission risk include semen,

vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, synovial fluid, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, pericardial

fluid, and amniotic fluid. HIV infection is not spread by air or water, insects, toilet seats, or

casual contact, such as washing dishes or shaking hands.15

When estimating risk of acquisition, receipt of infectious blood products and IVDU carry the

highest risk. Sexual acquisition is dependent on the infected patient's HIV RNA plasma levels,

number of encounters with an infected partner, and type of sexual contact. Receptive anal sex

carries a higher risk of acquisition than penile vaginal intercourse.13

Infection Control Practices in the Health Care Setting

From an infection control perspective, percutaneous needlesticks and exposure to bodily fluids

are primary risk factors for HIV transmission. Data presented at the 2015 Conference on

Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections indicated the last case of nosocomial transmission

occurred in 1999, which serves as a testament to the effectiveness of universal precautions and

postexposure prophylaxis.16 The purpose of Occupational Safety and Health Administration universal workplace precautions is to prevent parenteral, mucous membrane, and nonintact

skin exposures to blood-borne pathogens. These precautionary measures include17

- Using appropriate barriers such as a gown, gloves, and eye protection

- Handling and disposing of needles and other sharps safely

- Immediately washing skin surfaces after contact with blood or bodily fluids

The risk of acquiring a blood-borne pathogen through a needlestick injury is quantifiable in

what is commonly referred to as the Rule of 3s18:

- For hepatitis B virus (HBV) the risk is 30%

- For hepatitis C virus (HCV) the risk is 3%

- For HIV infection the risk is 0.3%.

In the event that an occupational exposure does occur, health care workers should wash

wounds and skin with soap and water, flush mucous membranes with water, and determine

source patient's HIV status when possible.18 Multiple state laws indicate that a patient must

understand and agree to HIV testing (i.e., informed consent), which means the patient (not the

health care provider) determines if testing may take place.19 Procedures related to informed

consent in Florida are discussed later in this manuscript.

Methods of prevention

The primary modes of HIV transmission are sexual intercourse, percutaneous injury, and

injection drug use. However, over the past several decades, a more detailed understanding of

HIV transmission has led to the development of various preventive measures, including safer

sex practices, needle exchange programs, and preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis.

Safer sex practices

Concerning safer sex practices, the following patient recommendations may help reduce the

risk of HIV transmission17:

- Limiting the number of sexual partners: Having multiple partners increases the chances of

coming into contact with someone whose viral load is not suppressed or someone who has

a sexually transmitted disease (STD).

- Choosing low-risk sexual behaviors: Anal receptive sex is the highest-risk sexual activity

followed by vaginal and oral sex, respectively.

- Using condoms: Female condoms are just as effective as male condoms at preventing HIV

and STDs. With regard to male condoms, latex products provide the best defense against

HIV infection because natural membrane condoms (lambskin) are porous, which limits their

ability to protect against HIV and STDs. Importantly, even though male and female condoms

are highly effective at reducing HIV transmission, neither is completely effective.

- Getting tested: For sexually active people, annual testing for STDs is recommended,

considering these infections can increase the likelihood of transmitting HIV or acquiring it

from others.

- Remaining adherent to treatment: For people who are HIV positive, it is important that

they initiate and stay on antiretroviral treatment because these strategies have shown to

greatly reduce the possibility of transmitting HIV infection to others.

Injection drug use

For individuals who engage in IVDU, the best method to reduce HIV transmission is to stop

using drugs altogether. However, some individuals find it difficult to stop or refuse to seek help.

In these circumstances, health care practitioners can recommend the following interventions,

which may help reduce HIV transmission17,20:

- Use only new, sterile needles, syringes, and other injection equipment—and never share.

- Only when new equipment is unavailable, clean used needles and syringes with bleach,

which may reduce the risk of transmitting or acquiring HIV. A document from the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website provides more detailed information about

syringe disinfection practices for individuals who cannot stop using drugs:

https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/31783.

- Dispose of needles and syringes safely using a sharps container and keep used needles and

syringes away from other people.

- Encourage patients to discuss pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and nonoccupational

postexposure prophylaxis with health care practitioners. Each of these interventions is

discussed below.

Pre-exposure Prophylaxis

The U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) guidelines recommend evaluating male and female

patients whose sexual or injection drug behaviors place them at high risk of acquiring HIV

infection.21 While efforts are ongoing to diagnose and treat patients, clinics in the U.S. have

emphasized PrEP to prevent new infections in high-risk seronegative patients or serodiscordant

couples.

The only PrEP medication regimen approved by the FDA is tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada), a

fixed-dose combination tablet that is administered once daily. It is important to note that

tenofovir and emtricitabine are available as individual agents; however, they should not be

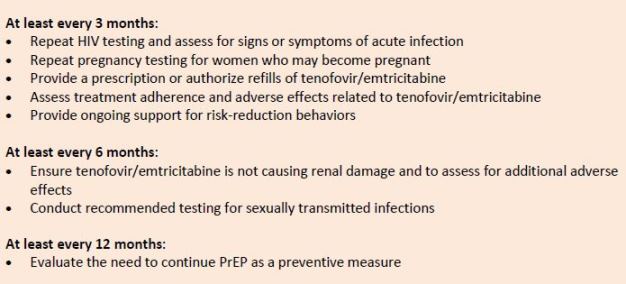

prescribed individually as PrEP. Table 2 describes the evaluation protocol and timeframes for

patients who receive PrEP to determine the overall safety and effectiveness of

tenofovir/emtricitabine and to assess for signs and symptoms of HIV infection.21

| Table 2. Recommended Monitoring for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis |

|

| Source: Reference 21 |

Clinical studies have validated PrEP's overall efficacy. One of the first studies to demonstrate

benefit, the Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Study, evaluated a daily

tenofovir/emtricitabine regimen compared with placebo in a MSM patient population.22 PrEP

reduced risk of HIV acquisition by an average of 44% among patients randomized to receive

active drug. Despite these findings, providers have been hesitant to prescribe pre-exposure

drug regimens because of concerns related to cost, fostering antiretroviral resistance, drug

toxicity, and behavioral risk compensation (adjustment of individual behavior in response to

perceived changes in risk; people tend to behave more cautiously if their perception of risk or

danger increases, and less cautiously when they feel protected). Yet studies have not

substantiated any of these concerns.23,24

Postexposure Prophylaxis

Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) involves taking 3 or more antiretroviral medications as soon as

possible after an individual has been exposed to potentially HIV-infected material. PEP

interventions are indicated after 2 types of exposures: occupational PEP and nonoccupational

PEP.13,18

- Occupational PEP (oPEP) interventions are administered when an individual is exposed

to a potential source of HIV in the workplace (e.g., hospital setting).

- Nonoccupational PEP (nPEP) interventions are administered when a potential HIV

exposure occurs outside the workplace (e.g., injection drug use, a sexual assault,

unprotected sex).

Multiple government agencies collaborated in 2011 to form the USPHS Working Group for the

purpose of updating the 2005 Guidelines for the Management of Occupational Exposures to HIV

and Recommendations for Postexposure Prophylaxis. The updated guidelines indicate oPEP

regimens should treat all occupational exposures with at least 3 antiretroviral drugs, and

patients should continue the regimen for 28 days.18 Specifically, tenofovir/emtricitabine plus

raltegravir is considered first-line therapy because this combination is tolerable, potent,

convenient, and has limited drug interactions. Alternative oPEP drug regimens can be found by

accessing the updated USPHS guidelines at the following CDC website: http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/20711. Notably, the drugs listed below are not recommended

to be included in PEP regimens for the following reasons18:

- Nevirapine is contraindicated because of serious toxicities related to liver and muscle

damage.

- Abacavir should only be used under the direction of expert consultation because of the

need to identify individuals who are at high risk for hypersensitivity reactions (those who

carry the HLA-B*5701 allele).

- Enfuvirtide is not recommended because it requires subcutaneous administration.

- Efavirenz should not be used during the first trimester of pregnancy or for women who may

become pregnant while taking PEP because of possible teratogenicity.

Multiple organizations, including CDC, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

HIV/AIDS Bureau, and the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute offer clinical

guidance for nPEP.18,25,26 Patients who may have been exposed to HIV infection and are

considered to be high risk should commence a 3-drug antiretroviral combination immediately,

and the regimen should be continued for 28 days. The Medical Care Committee at the New

York State Department of Health and HRSA HIV/AIDS Bureau now recommend tenofovir/emtricitabine plus raltegravir as the preferred initial nPEP regimen.25,26 Zidovudine is

no longer a preferred therapy because of its high rate of treatment-limiting adverse effects.

For individuals who may have been exposed to a source of HIV-infected material, successive

HIV testing and laboratory panels are necessary to rule out infection and assess drug toxicity

(when therapy is recommended). Suggested patient follow-up is typically included in health

care facility protocols, or in oPEP and nPEP guidelines. Health care professionals may also

contact a PEP hotline for guidance through CDC and University of California at San Francisco at

(888) 448-4911. Moreover, when either type of exposure occurs, pharmacists and other health

care professionals should at a minimum provide the following patient education13,25:

- Educate high-risk individuals regarding the availability of PrEP and nPEP.

- Advise patients to begin PEP regimens as soon as possible (when a drug regimen is

indicated). Data suggest uncertainty regarding clinical benefit/protection if the regimen

is not commenced within 72 hours of exposure.

- Educate patients about the efficacy of PEP, timely initiation of the medications,

adherence to the regimen for 28 days, and the importance of preventing additional HIV

exposures during this time.

- Counsel patients about the importance of committing to serial HIV and laboratory

testing to minimize drug toxicity and to rule out HIV infection. Re-evaluation of patients

who have been exposed should begin within 72 hours after the initial exposure.

- Instruct patients to contact their health care provider immediately if they experience

uncomfortable adverse effects after commencing a PEP drug regimen. An alternative

regimen may be needed to lessen adverse effects and improve adherence.

- Advise patients who have been exposed to use latex barriers with their sex partners

until transmission of HIV infection has been ruled out.

- Counsel patients about the symptoms of HIV infection and instruct them to contact their

medical provider immediately if symptoms develop.

- Refer sexual assault victims to a qualified health care professional who can provide a

baseline evaluation and appropriate counseling.

Diagnostic Tests

As antiretroviral therapy has been revolutionized, so has the ability to test and diagnose

patients with HIV infection. Available HIV tests include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

(ELISA), Western blot, HIV RNA, and rapid HIV tests. Two rapid HIV tests, OraQuick In-Home HIV

Test and the Home Access HIV-1 System, are both FDA-approved over-the-counter in-home test

kits.

OraQuick In-Home HIV Test provides results in approximately 20 minutes and only requires an

oral swab. Studies have shown Oraquick has an expected performance of approximately 92%

for test sensitivity (i.e., the percentage of results that will be positive when HIV is present) and

an expected performance of 99.9% for test specificity (i.e., the percentage of results that will be

negative when HIV is not present).27 The rapid availability of a test result makes OraQuick

appealing to patients. However, the speed at which a test result is produced must be carefully

weighed against false negatives that may occur during the "window period" as well as the need

for subsequent evaluation based on the initial test result. Accordingly, pharmacists have the

opportunity to play an integral role in providing guidance to patients regarding testing.

The Home Access HIV-1 System is also available over-the-counter. Notably, this system requires

a blood sample that must be shipped to a laboratory for testing. Patients are able to call

approximately 1 week later with a code specific to their kit to receive their test results. Studies

have shown the sensitivity and specificity of the Home Access HIV-1 System to be greater than 99.9%.28

The Western blot has been the confirmatory assessment after a positive result from an ELISA

test. However, the Western blot has been supplanted by HIV-1/2 differentiation immunoassay

because the latter provides earlier identification of positive test results.29

Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy—Medication Adherence and Drug Interactions

Treatment options and health care services for patients with HIV infection have advanced

significantly since the virus was discovered more than 3 decades ago. Clinicians are able to

select antiretrovirals from 6 different drug classes in order to construct an ideal patient-specific

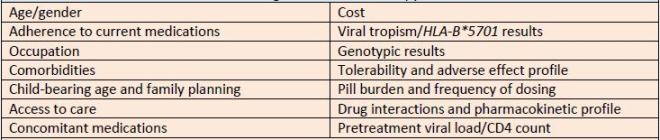

drug regimen. However, numerous factors must be considered before making therapeutic

decisions. Table 3 highlights these decisions.

| Table 3. Factors to Consider When Selecting Antiretroviral Therapy |

|

| Source: References 11 ,30 |

Perhaps 2 of the most important factors that must be taken into consideration before initiating

antiretroviral medications are the patient's willingness to adhere to a prescribed drug regimen

and drug-drug interactions. Several strategies to improve adherence and retention in care

include11:

- Assessing the patient's knowledge of HIV infection

- Providing each patient with necessary HIV-related resources

- Recognizing the patient's readiness to start antiretroviral therapy

- Identifying barriers or reasons for nonadherence at baseline and with every clinic visit

- Involving the patient in antiretroviral drug selection

- Using treatment adherence interventions such as mobile applications (apps)

- Systematically monitoring patients to retain them in care

Drug-drug interactions must be considered as well. Notably, certain antiretroviral drug classes

have shown a greater propensity for clinically relevant interactions because of their

pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles. PK interactions may occur during oral absorption, metabolism, or

elimination of an antiretroviral or the interacting drug. Three common mechanisms that

influence the oral absorption of select antiretrovirals include elevated gastrointestinal (GI) pH,

cationic chelation, and changes to p-glycoprotein function.11 Many patients who are on

antiretroviral medications take antacids, histamine 2 blockers (H2 blockers), or proton pump

inhibitors (PPIs). Consequently, systemic concentrations of atazanavir and rilpivirine, among

others, are reduced because each of these agents requires an acidic gastric medium for oral

absorption.11 Concomitant PPIs significantly affect rilpivirine's bioavailability and, therefore,

PPIs are contraindicated. For patients who require stomach acid-reducing drugs, counseling

patients to take antiretrovirals 2 hours after antacid therapy or 12 hours after an H2 blocker or

PPI may help mitigate concerns regarding drug-drug interactions.11

Two major enzyme systems play a significant role in drug-drug interactions: Cytochrome P-450

(CYP450) enzymes and uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1. The

CYP450 enzyme system influences many antiretroviral's metabolic breakdown, including non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI), protease inhibitors (PI), and entry

inhibitors. PI-based regimens are particularly challenging because they are coadministered with

ritonavir or cobicistat (pharmacoenhancers). The purpose of a pharmacoenhancer is to increase

or "boost" an antiretroviral medication's concentration. However, because numerous

medications share metabolic pathways, phamacoenhancers' boosting effect frequently leads to

various CYP-mediated interactions. In addition, the coadministration of pharmacoenhancers

with systemic and local corticosteroids can result in adrenal insufficiency and Cushing's

syndrome. As a result, corticosteroids are not recommended to be coadministered with

boosted antiretroviral regimens unless the potential benefits outweigh the risks. Notably, data

suggest beclomethasone may be the safest treatment option when an inhaled corticosteroid

must be coadministered with a boosted antiretroviral drug regimen.11

The uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 enzyme system is primarily

responsible for the metabolism of integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir.

Consequently, each of these medications is mostly devoid from CYP-mediation drug

interactions. For a comprehensive list of CYP450-mediated drug interactions involving

antiretrovirals and commonly used acute and chronic medications, the following link to the

Department of Health and Human Services HIV guidelines is recommended: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf.11

Antiretroviral Medications

HIV treatment guidelines were revised significantly in 2015 and again in January 2016.11 Efavirenz is no longer recommended as a preferred treatment option because of its central

nervous system-related adverse effects, which have negatively affected patient tolerability.

Atazanavir boosted with ritonavir is now considered an alternative PI-based regimen, based

largely on outcomes from the AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5257 study.31 Similar to efavirenz,

atazanavir's efficacy is reduced due to adverse effects that limit patient tolerability.

Additionally, integrase strand transfer inhibitors are now preferred treatment options because

of improved patient tolerability and overall drug efficacy.

For both treatment-experienced and treatment-naive patients, antiretroviral therapy is

recommended to reduce the risk of disease progression and prevent the transmission of HIV

infection. The 2016 update strengthened recommendations about when to start antiviral

therapy, emphasizing that all individuals, regardless of CD-4 count, should start antivirals. When

constructing an antiretroviral drug regimen for any patient, 3 or more fully active agents should

be included. For treatment-naive patients, 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)

are universally recommended in combination with a third active drug from 1 of the following 2

drug classes: an integrase inhibitor or a boosted PI. Tables 4 through 9 detail available

antiretroviral treatment options, including adult dosing and clinical notes about each therapy.

Currently recommended drug regimens for treatment-naive patients according to updated HIV

guidelines include11:

- Abacavir/lamivudine/dolutegravir only for patients who are HLA-B*5701 negative

- Tenofovir/emtricitabine plus dolutegravir

- Tenofovir/emtricitabine plus raltegravir

- Tenofovir/emtricitabine/cobicistat/elvitegravir only for patients with pretreatment

estimated creatinine clearance of ≥70 mL/min

- Tenofovir/emtricitabine plus darunavir plus ritonavir

- Elvitegravir/cobicistat/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine for patients with estimated

creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min

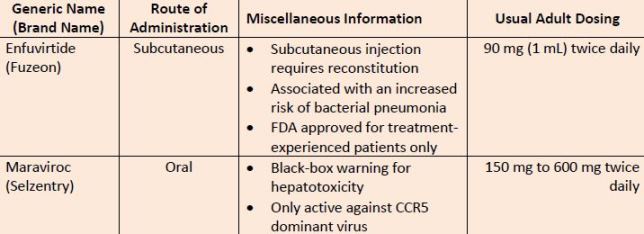

| Table 4. Entry Inhibitors |

|

| Source: Reference 11 |

| Abbreviations: CCR5, C-C chemokine receptor type 5. |

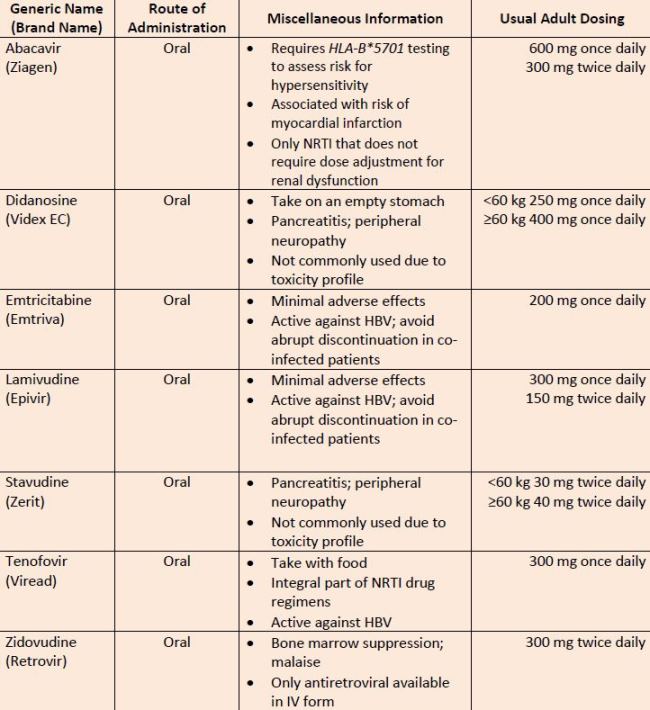

| Table 5. Nucleoside/Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors |

|

| Source: References 11 ,32, 33 |

| Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; IV, intravenous; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; mg, milligrams. |

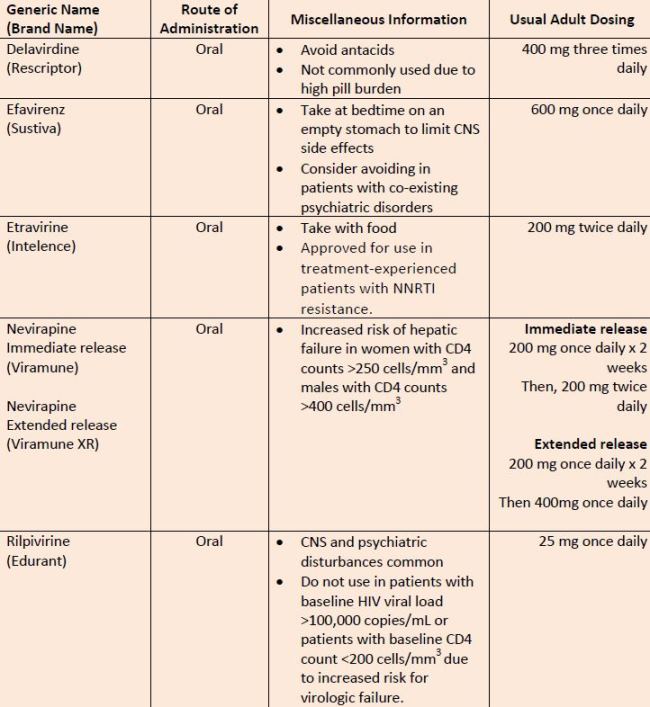

| Table 6. Nonnucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors |

|

| Source: References 11 ,34-36 |

| Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system. |

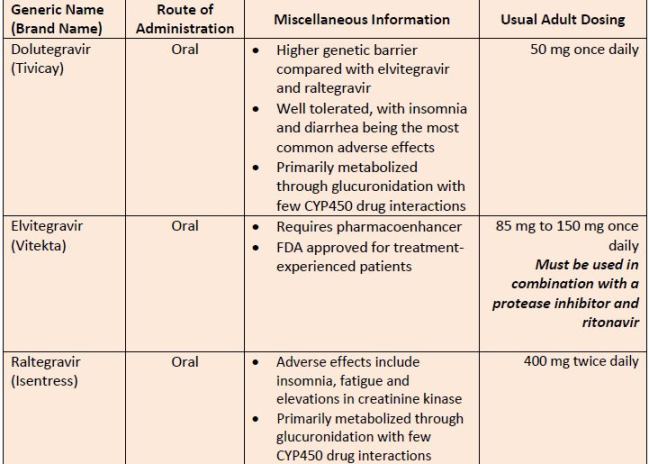

| Table 7. Integrase Inhibitors |

|

| Source: References 11 |

| Abbreviations: CrCl, creatinine clearance; CYP450, cytochrome P-450. |

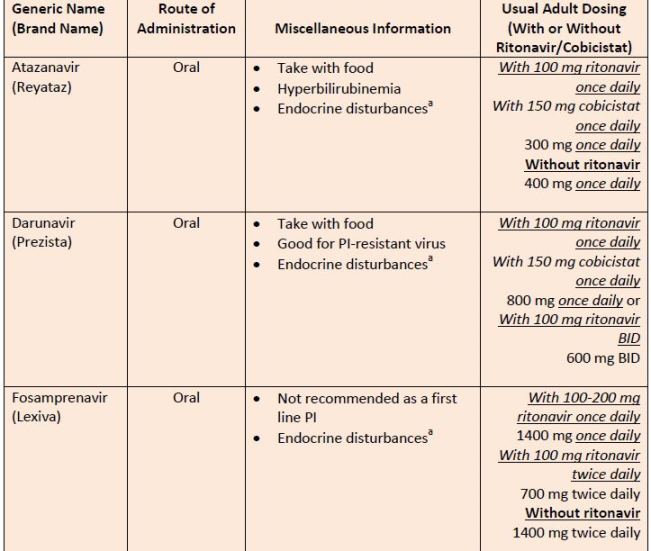

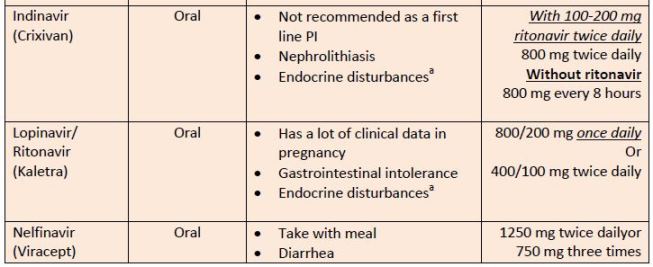

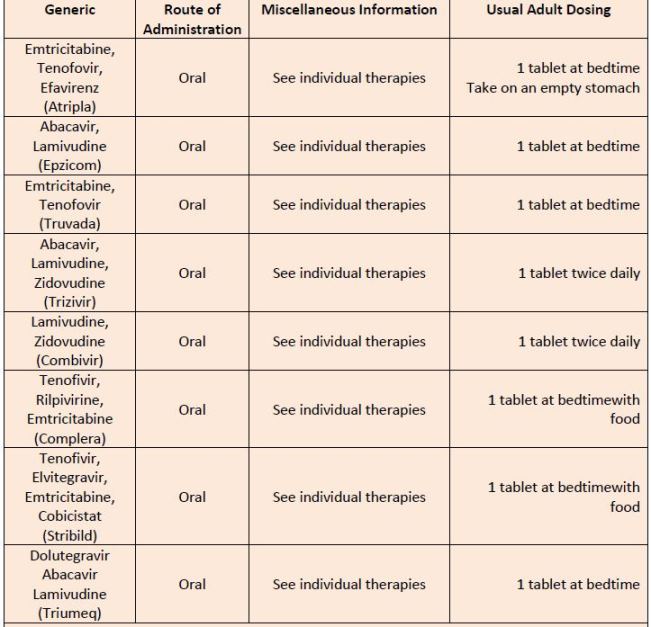

| Table 8. Protease Inhibitors |

|

| Source: Reference 11 |

| Abbreviations: PI, protease inhibitor.a

aEndocrine disturbances = insulin resistance (type 2 diabetes mellitus), lipid abnormalities, peripheral fat loss, and central fat accumulation |

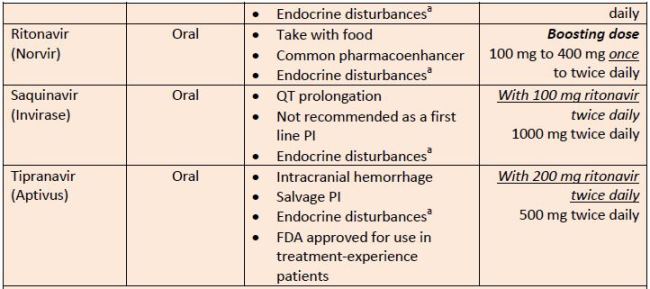

| Table 9. Antiretroviral Combination Products |

|

| Source: Reference 11 |

Treatment-experienced patients can be more challenging than treatment-naive patients

because therapeutic strategy is often driven by genotypic resistance/mutations, medication

adherence, and exposure to other agents.11,37 Common genetic mutations include M184V and

K103N. The M184V mutation has a high level of resistance to lamivudine and emtricitabine

while K103N shows high levels of resistance to efavirenz and nevirapine.11 As a result,

genotypic, phenotypic, and co-receptor tropism assays are recommended to be used to assess

viral strains and guide the selection of antiretroviral drug regimens.11 Genotypic assays test for

the presence of mutations known to confer viral resistance. Phenotypic assays (typically

reserved for complex patterns of resistance) test for the antiretroviral inhibitory concentration

required to decrease HIV replication by 50%. Co-receptor tropism assays are recommended

when the CCR5 antagonist, maraviroc, is being considered or if virologic failure occurs during

CCR5 antagonist therapy.11

Two drawbacks to resistance testing include: (1) testing is not beneficial in patients who have a

plasma viral load that is less than 500 copies/mL, and (2) testing requires expert consultation.

On the other hand, resistance testing has shown to be an independent predictor of virologic

outcome and carries the potential to limit patient drug exposures and toxicities. HIV infection

guidelines recommend resistance testing in the following circumstances11:

- At patient entrance into care

- In treatment-naive patients with chronic HIV infection

- In treatment-experienced patients who have shown complex-resistance patterns

- All pregnant women with HIV infection

- Virologic failure during antiretroviral therapy

- Suboptimal suppression of viral load after initiating antiretroviral therapy

- Before initiating antiretroviral therapy in acute HIV infection

Generally speaking, a new regimen for a treatment-experienced patient should include 2 or

more antiretrovirals that are expected to have uncompromised activity on the basis of the

patient's treatment history and drug resistance test results. For instance, protease inhibitors

and dolutegravir have high genetic barriers (the threshold above which clinically meaningful

resistance develops, or the ease to which resistance develops, to a drug or a drug class) and

should be considered in nonadherent patients. Conversely, efavirenz and rilpivirine have low

genetic barriers and may not be appropriate in this patient population.11 Notably, NRTI-sparing

regimens have been used in both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients,

although results have been mixed.38-40 Assessing and managing a patient who has experienced

treatment failure is complex. As a result, expert consultation should be considered.

Opportunistic Infections—Primary Prophylaxis and Vaccines as Standard of Care

Opportunistic infections (OIs) are pathognomonic (signs that indicate a particular disease is

present beyond any doubt) in many new cases of HIV infection. The risk of acquiring particular

OIs is based on the patient's immune status. For instance, when CD4 cells decline to less than

200 cells/mm3, patients are at increased risk of acquiring Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

(PJP).12 Patients who are infected with PJP often present with multiple respiratory symptoms;

hypoxemia and radiologic findings appear to be most suggestive of PJP. HIV-infected patients

should receive primary prophylaxis for PJP when their CD4 counts fall below 200 cells/mm3, if

CD4% is less than 14, or if oropharyngeal candidiasis is present. Prophylactic therapies include

(but are not limited to)

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 1 double-strength tablet orally once daily

or 3 times weekly

- Dapsone 100 mg orally once daily

- Dapsone 50 mg orally once daily plus pyrimethamine 50 mg and leucovorin 25 mg once

weekly

- aerosolized pentamidine 300 mg administered once a month via the Respirgard II

nebulizer

- atovaquone 1500 mg orally once daily

Of the above-mentioned treatment options, TMP-SMX is preferred. When a patient's CD4 count

reaches or exceeds 200 cells/mm3 for at least 3 months in response to antiretroviral therapy,

primary prophylaxis may be discontinued.12

When CD4 cells decline to fewer than 50 cells/mm3, patients are at increased risk of acquiring

toxoplasmosis encephalitis, caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii.12 Toxoplasmosis is

almost exclusively a reactivation phenomenon, considering most patients who develop the

disease are seropositive for anti-toxoplasma immunoglobulin G antibodies.12 Primary

prophylaxis for toxoplasmosis should be initiated in toxoplasma IgG patients with CD4 counts

below 100 cells/mm3. The drug regimen of choice is TMP-SMX 1 double-strength tablet daily.

For patients seropositive for Toxoplasma gondii who cannot tolerate TMP-SMX, recommended

alternatives for prophylaxis against toxoplasmosis include dapsone plus pyrimethamine plus leucovorin or atovaquone with or without pyrimethamine plus leucovorin.12 Primary

prophylaxis for toxoplasmosis may be discontinued when a patient's CD4 count reaches or

exceeds 200 cells/mm3 for at least 3 months in response to antiretroviral therapy.12

Unlike with PJP, patients may be able to take protective measures against the acquisition of

toxoplasmosis because undercooked meats and cat litter have been identified as vectors of

transmission. While TMP-SMX is an appropriate prophylactic regimen for toxoplasmosis, it

should not be used to treat patients with active disease. Patients with active disease should be

treated with a 3-drug combination that consists of sulfadiazine plus pyrimethamine plus leucovorin for at least 6 weeks.12

Moreover, when CD4 counts decline to fewer than 50 cells/mm3, patients are at increased risk

for mycobacterial infections, in particular Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). However,

primary prophylaxis should not be initiated until the CD4 cell count falls to fewer than 50

cells/mm3 and disseminated infection has been ruled out. Aside from impaired immune

function, other factors may also contribute to active disease, including high viral load, previous

opportunistic infections, and colonization with MAC in the respiratory or gastrointestinal

tract.12 In patients who are treatment-naive, active disease can mimic tuberculosis, with night

sweats, fever, and weight loss. The prophylactic agents of choice are azithromycin and

clarithromycin. If a patient is unable to tolerate either agent, rifabutin is an option; however,

rifabutin has many drug-drug interactions complicating its use in HIV drug regimens.

Tuberculosis (TB) should be ruled out before rifabutin is used for MAC prophylaxis because

treatment with rifabutin could result in acquired resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in

patients who have active TB. Primary prophylaxis for MAC may be discontinued when a

patient's CD4 count reaches or exceeds 100 cells/mm3 for at least 3 months in response to

antiretroviral therapy.12 However, MAC prophylaxis should be reintroduced if a patient's CD4

count falls below 50 cells/mm3 again.

Globally, TB remains a common coinfection with HIV. Patients with latent tuberculosis infection

(LTBI) are at significantly higher risk of reactivation than patients who do not have HIV

infection. Patients who are coinfected should receive isoniazid 300 mg orally once daily plus pyrodixine 25 mg orally once daily for 9 months.12 However, before prophylactic treatment is

started, active tuberculosis must be excluded by a negative chest radiograph and the absence

of symptoms. Alternative LTBI drug regimens include rifampin 600 mg orally once daily for 4

months or rifabutin (dose adjusted for concomitant antiretroviral therapy) for 4 months.

Rifabutin is a less potent cytochrome CYP3A4 inducer than rifampin and is preferred in patients

receiving PIs. Once-weekly isoniazid plus rifapentine is not recommended for LTBI-HIV

coinfection because rifapentine can result in development of rifamycin resistance in HIV-infected patients.12 For patients with active TB, there has been much controversy regarding

when to initiate treatment. The Starting ART at 3 Points in TB and Cambodian Early versus Late

Introduction of Antiretroviral Drugs trials showed that earlier therapy was associated with a

mortality benefit.41,42

In addition to prophylaxis of select OIs, vaccines are an important preventive measure in

immunocompromised patients. Table 10 lists CDC-recommended vaccinations for patients with

HIV infection.43 Notably, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) has recently been

recommended for use in adults with HIV infection. Specifically, all patients with HIV infection

who have never received pneumococcal vaccine should receive a single dose of PCV13,

followed by a dose of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) no earlier than

8 weeks later.12 However, it may be preferable to wait until a patient's CD4 count is 200

cells/mm3 or higher before initiating PPSV23.12 Live vaccines should generally be avoided in

patients with HIV infection, especially those with CD4 counts lower than 200 cells/mm3.

FLORIDA LAW RELATED TO HIV/AIDS TESTING

In 1988, Florida became one of the first states to adopt comprehensive legislature to manage

the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which became known as the Florida Omnibus AIDS Act. Besides

mandating specific continuing education requirements for health care professionals in Florida,

the Act requires health care workers who order HIV tests to44:

- Obtain informed consent from the patient

- Confirm positive preliminary test results through subsequent tests before informing the

patient of the result

- Take all reasonable efforts to notify the test subject about the test results

- Adhere to special handling requirements of superconfidential HIV test results

- Follow correct procedures when notifying parties other than the patient of HIV test results

- Report positive HIV test results to the local county health departments

Informed consent

According to Florida law, a patient must understand and agree to HIV testing, which means the

patient, not the health care provider, determines if testing may occur.44 Importantly, when

obtaining informed consent, which does not necessarily have to be in writing, the health care

provider must consider the patient's age, mental capacity, and language skills. In addition,

health care providers must explain the following information that pertains to testing44: (1) any information identifying the patient and the test results are confidential and protected against

further disclosure; (2) individuals who test positive will be reported to the local county health

department; and (3) anonymous testing is available but the provider must provide locations of

alternate testing sites to the patient. Notably, minors in the state of Florida (children under the

age of 18) are considered adults for the purposes of consenting to examination and treatment

of STDs, including HIV testing and treatment. Florida specifically prohibits telling a minor's

parents about the examination or treatment for an STD, including HIV infection.44

Health care providers who perform HIV testing without patient informed consent are subject to

discipline by their licensing bodies, including fines and license suspension or revocation.

However, Florida law recognizes several circumstances that release health care providers from

obtaining informed consent including44:

- Pregnancy: Pregnant women must be advised that the health care provider attending to

them will conduct an HIV test; however, the patient has the right to refuse, which is

required to be in writing and must be placed in the patient's medical record.

- Emergencies: A provider may test without consent in a "bona fide" medical emergency,

provided documentation is placed in the chart that testing is necessary to provide

appropriate medical care.

- Therapeutic privilege: Informed consent may be bypassed if the medical provider

documents in the medical record that informed consent would be detrimental to the health

of a patient suffering from an acute illness and test results are necessary for diagnostic

purposes and to help guide appropriate medical care.

- Sexually transmissible diseases: Florida laws permit HIV testing for sexually transmissible

diseases in certain patient populations, such as convicted prostitutes, inmates prior to

release, and select medical examiner cases, without consent.

- Criminal acts: Victims of criminal offenses that involve transmission of bodily fluids may

require the person convicted of the offense to be tested for HIV infection.

- Organ donations: Certain provisions permit testing without consent in specific specialty

areas, such as organ and tissue donations.

- Research: Established epidemiologic research methods that ensure patient anonymity are

exempted from consent requirements.

- Abandoned infants: If a physician determines that an HIV test is medically indicated, but

the infant's parent(s) or legal guardian cannot be located after reasonable attempts, the

test may be performed without consent.

- Significant exposure: Under limited circumstances, the blood of a source of significant

exposure to medical personnel may be obtained without consent.

- Repeat HIV testing: Renewed consents are not required when monitoring the clinical

progress of a previously diagnosed HIV-positive patient or to monitor for possible

conversion from a significant exposure.

- Judicial Authority: A court has the authority to order an HIV test without the individual's

consent.

Notification Responsibilities and Confidentiality

HIV testing was traditionally performed using ELISA and Western blot tests, which required an

extended period of time to generate results.45 However, rapid HIV tests produce results in as

few as 20 minutes. Data show that rapid HIV tests substantially increase the number of

individuals who are tested as well as the number of individuals who receive their results in a

timely manner, expediting the delivery of patient counseling, education, and treatment

services.46

Health care professionals who order HIV tests have an obligation to make all reasonable efforts

to notify an individual of his or her result.44 If a preliminary HIV test result is positive, the

Omnibus AIDS Act specifies that a separate confirmatory HIV test must be performed before

the final result can be disclosed to a patient. Conversely, a negative preliminary test result is

considered definitive and no further testing is required. The amount of information that is

required to be disseminated to the patient depends on the result of the HIV test.44 For instance,

if a patient has a negative test result, the Act does not specify the amount of information that

must be communicated to the patient beyond discussing the importance of preventing

transmission. Conversely, if an HIV test is positive, the patient must be counseled on the

following44: (1) the availability of appropriate medical and support services; (2) the importance

of notifying partners who may have been exposed; and (3) preventing HIV transmission. Health

care providers who order such tests must report all positive HIV test results to the county

health department.

While patient medical records are generally considered confidential under most state and

federal laws, the Omnibus AIDS Act renders any information related to HIV testing of an

identifiable person and the results of such testing superconfidential, which means health care

professionals have additional obligations to protect these data.45 The Act specifically outlines

situations in which HIV test results may be disclosed, including the following (the list is not

complete)44:

- To the test subject or his or her legal representative.

- Employees and agents of health care providers may discuss the HIV status of an

individual among themselves if they need to know.

- Health care providers may share HIV test information with other providers for the

purpose of diagnosis and treatment.

- Health care providers who are involved in the delivery or a newborn may note the

mother's HIV test status in the medical record of the newborn.

- Medical examiners must report positive HIV test results to the Florida Department of

Health.

- In select circumstances, health care providers are permitted to tell the sexual and

needle-sharing partners of HIV-positive patients that they have been exposed to HIV.

- Adults responsible for a child who has been placed in foster care or adoption may be

told the child's HIV status, provided they are directly involved in the child's placement,

care, or custody.

- Appropriate authorities in situations related to child sexual abuse and neglect may be

notified of the child's HIV status.

- Hospital staff and health care workers who have had significant exposure to high-risk

body fluids may be notified on a need-to-know basis.

The punishment for debasing the confidentiality laws of the Omnibus HIV Act can be quite

severe, considering it is a first degree misdemeanor. Anyone who violates the Act is subject to

up to 1 year of imprisonment. Further, a 1998 amendment to the Act made it a third degree

felony, which carries punishment of up to 5 years' imprisonment for anyone who maliciously

breaches the confidentiality of STD information. Last, the Florida Supreme Court held that

anyone may be sued for negligence based on the violation of the Act's duty of confidentiality.44

Future Directions and Conclusion

Antiretroviral pharmacotherapy has improved dramatically over the past 20 years, and efforts

to develop vaccines and a cure for HIV infection are ongoing. The current drug pipeline includes

innovative agents that seek to simplify or make existing antiretroviral therapies safer. These

drugs include a new integrase inhibitor (cabotegravir), an attachment inhibitor (BMS-663068),

and a novel prodrug of tenofovir (tenofovir alafenamide).47-49

Initiation of antiretroviral therapy is more important today than ever before because of the

direct patient and public health benefits. With the development of novel agents, continued

access to care, and government funding, many of the existing challenges health care

practitioners face today could be concerns of the past. Clinicians should always consult the

most recent version of the HIV guidelines to ensure they deliver the most appropriate care.

References

1. Conrad C, Bradley HM, Broz D, et al. Community outbreak of HIV infection linked to injection drug

use of oxymorphone—Indiana, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.

2015;64(16):443-444.

2. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global Report: UNAIDS Report on

the AIDS Epidemic, 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2013. NLM classification: WC 503.6. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en_1.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2015.

3. Maartens G, Celum C, Lewin S. HIV infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. Lancet. 2014;384:258-271.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology of HIV infection through 2013.

Accessed at https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/hiv-surveillance-epidemiology-hiv-infection-through-2013, June 13, 2016.

5. Reif S, Whetten K. Southern HIV/AIDS Strategy Initiative (SASI) Update: The Continuing HIV

Crisis in the US South. Durham, NC: Duke Center for Health Policy and Inequalities Research;

2012. Accessed at https://southernaids.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/sasi-update-the-continuing-hiv-crisis-in-the-us-south.pdf, June 17, 2015.

6. Hurt CB, Dennis AM. Putting it all together: lessons from the Jackson HIV outbreak

investigation. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(3):213-215.

7. Aral SO, Padian NS, Holmes KK. Advances in multilevel approaches to understanding the

epidemiology and prevention of sexually transmitted infections and HIV: An overview. J

Infect Dis. 2005;191(suppl 1):S1-S6.

8. Nilsson J, Kinloch-de-Loes S, Granrath A, et al. Early immune activation in gut-associated and

peripheral lymphoid tissue during acute HIV infection. AIDS. 2007;21:565-574.

9. Gray F, Scaravilli F, Everall I, et al. Neuropathology of early HIV-1 infection. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:1-15.

10.Daar ES, Pilcher CD, Hecht FM. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2008;3:10.

11. Department of Health and Human Services., Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults

and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and

adolescents. Accessed at https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf, April 15, 2015.

12. Department of Health and Human Services, Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of

opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV

Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Accessed at

http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf, June 15, 2016.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis

after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United

States: recommendations from US Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR

Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR2):1-20.

14. Busch MP, Kleinman SH, Nemo GJ. Current and emerging infectious risks of blood

transfusions. JAMA. 2003;289(8):959-962.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV transmission. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/transmission.html.,February 14, 2015.

16. Joyce MP, Kuhar D, Brooks JT. Notes from the Field: Occupationally acquired HIV infection among health care workers—United States, 1985-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;63(53):1245-1246.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Occupational HIV transmission and prevention

among health care workers. Accessed at https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/occupational-hiv-transmission-and-prevention-among-health-care-workers-0, June 15, 2016.

18. Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the

management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and

recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(9):875-892.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State HIV laws. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/index.html, July 2, 2015.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IDU/HIV prevention: syringe disinfection for

injection drug users, 2004. Accessed at https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/31783, June 15,

2016.

21. US Public Health Service. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the

United States—2014: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf, June 15, 2016.

22. Paxton LA, Hope T, Jaffe HW. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection: what if it works?

Lancet 2007; 370:89-93.

23. Lehman DA, Baeten J, McCoy CO, et al. Risk of drug resistance among persons acquiring HIV

within a randomized clinical trial of single or dual-agent pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Infect

Dis. 2015;211(8):1211-1218.

24. Mugwanya KK, Donnell D, Celum C, et al. Sexual behaviour of heterosexual men and women

receiving antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(12):1021-1028.

25. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services

Administration. Guide for HIV/AIDS Clinical Care. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health

and Human Services; 2014.

26. New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. Update: HIV prophylaxis following

non-occupational exposure. Accessed at http://www.hivguidelines.org/clinical-guidelines/post-exposure-prophylaxis/hiv-prophylaxis-following-non-occupational-exposure/, July 2, 2014.

27. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Information regarding the Oraquick In-Home HIV Test.

Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/BloodBloodProducts/ApprovedProducts/PremarketApprovalsPMAs/ucm311895.htm, July 2, 2015.

28. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Information regarding the Home Access HIV-1 Test

System. Accessed

at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/BloodBloodProducts/ApprovedProducts/PremarketApprovalsPMAs/ucm311903.htm, July 2, 2015.

29. Branson B. The future of HIV testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55(suppl 2):S102-S105.

30. Clinical Care Options. First and foremost: choosing and using first-line antiretroviral therapy. Accessed at http://www.clinicaloptions.com/HIV/Treatment%20Updates/First-line%20ART/First-line_ART_Slides.aspx, July 2, 2015.

31. Lennox JL, Landovitz R, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of 3 nonnucleoside reverse

transcriptase inhibitor-sparing antiretroviral regimens for treatment-naive volunteers

infected with HIV-1: a randomized controlled equivalence trial. Ann Intern Med.

2014;161(7):461-471.

32. Cahn P, Andrade-Villanueva J, Arribas JR, et al. Dual therapy with lopinavir and ritonavir plus

lamivudine versus triple therapy with lopinavir and ritonavir plus two nucleoside reverse

transcriptase inhibitors in antiretroviral-therapy-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48 week

results of the randomised, open label, non-inferiority GARDEL trial. Lancet Infect Dis.

2014;14(7):572-580.

33. Sax P, Tierney C, Collier A, et al. Abacavir-lamivudine versus Tenofovir-emtricitabine for

initial HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(23):2230-2240.

34. Mollan KR, Smurzynski M, Eron J, et al. Association Between Efavirenz as Initial Therapy for

HIV-1 Infection and Increased Risk for Suicidal Ideation or Attempted or Completed Suicide:

An Analysis of Trial Data. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(1):1-10.

35. van Leth F, Andrews S, Grinsztejn B. The effect of baseline CD4 cell count and HIV-1 viral

load on the efficacy and safety of nevirapine or efavirenz-based first-line HAART. AIDS.

2005;19(5):463.

36. Molina J-M, Cahn P, Grinsztejn B, et al; for ECHO Study Group. Rilpivirine versus efavirenz

with tenofovir and emtricitabine in treatment-naive adults infected with HIV-1 (ECHO): a

phase 3 randomised double-blind active-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):238-246.

37. Cohen CJ, Andrade-Villanueva J, Clotet B, et al; for THRIVE Study Group. Rilpivirine versus

efavirenz with two background nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in

treatment-naive adults infected with HIV (THRIVE): a phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority

trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):229-237.

38. Ocfemia MC, Kim D, Ziebell R, et al. Prevalence and trends of transmitted drug resistance-associated mutations by duration of infection among persons newly diagnosed with HIV-1

infection: 5 states and 3 municipalities, US, 20062009. In: Proceedings from the 19th

Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 5-8, 2012. Seattle, WA.

Abstract 730.

39. Raffi F, Babiker AG, Richert L; for the NEAT001/ANRS143 Study Group. Ritonavir-boosted

darunavir combined with raltegravir or tenofovir-emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive adults

infected with HIV-1: 96 week results from the NEAT001/ANRS143 randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1942-1951.

40. Stellbrink HJ, Pulik P, Szlavik J, et al. Maraviroc (MVC) dosed once daily with

darunavir/ritonavir (DRV/r) in a 2 drug-regimen compared to emtricitabine/tenofovir

(TDF/FTC) with DRV/r; 48-week results from MODERN (Study A4001095). In: Proceedings

from the 20th International AIDS Conference; July 20-25, 2014. Melbourne, Australia.

41. Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs

during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(8):697-706.

42. Havlir DV, Kendall MA, Ive P, et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and

tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1482-1491.

43. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2015 Recommended Immunizations: By Health Condition. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-schedule-easy-read.pdf,

July 2, 2015.

44. Hartog JP, Robinson G. The Florida Omnibus AIDS Act: A Brief Legal Guide for Healthcare

Professionals. Florida Department of Health, Division of Disease Control and Health

Prevention, Bureau of Communicable Diseases, HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis Section; 2013.

Accessed at http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/operations_managment/_documents/Omnibus-booklet-update-2013.pdf,

February 9, 2015.

45. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: approval of a new rapid test

for HIV antibody. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/MMWR/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5146a5.htm,February 14, 2015.

46. Pottie K, Medu O, Welch V, et al. Effect of rapid HIV testing on HIV incidence and services in

populations at high risk for HIV exposure: an equity-focused systematic review. BMJ Open.

2014;4(12):e006859.

47. Margolis DA, Griffith S, St. Clair M, et al. Cabotegravir and rilpivirine as 2-drug oral

maintenance therapy: LATTE W96 results. In: Proceedings from the 2015 Conference on

Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 23-26, 2015; Seattle, WA. Abstract

554LB.

48. Thompson M, Lalezari J, Kaplan R, Pinedo Y. Attachment inhibitor prodrug BMS-663068 in

ARV-experienced subjects: week 48 Analysis. In: Proceedings from the 2015 Conference on

Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 23-26, 2015; Seattle, WA. Abstract 545.

49. Wohl D, Pozniak A, Thompson M, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) in a single-tablet

regimen in initial HIV-1 therapy. In: Proceedings from the 2015 Conference on Retroviruses

and Opportunistic Infections; February 23-26, 2015; Seattle, WA. Abstract 113LB.

Back to Top