Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Module 8: Providing Pharmaceutical Care and Products for Cats

Introduction

Nearly 35% of all households in the United States own at least one of the country’s 85.8 million pet cats.1 Although cats may suffer from many of the same diseases and conditions that humans do, therapies can vary significantly regarding drugs, doses, frequencies and routes of administration.

This activity is designed to impart a working knowledge of the feline disease states that are most likely to prompt a cat owner to have a prescription filled at a community pharmacy. It is intended as a primer for pharmacists to (1) begin to consider the significant species-specific variations in medical therapy for cats versus humans and (2) learn important techniques for due diligence for prescription review, caregiver counseling, and practice tips for caring for cats.

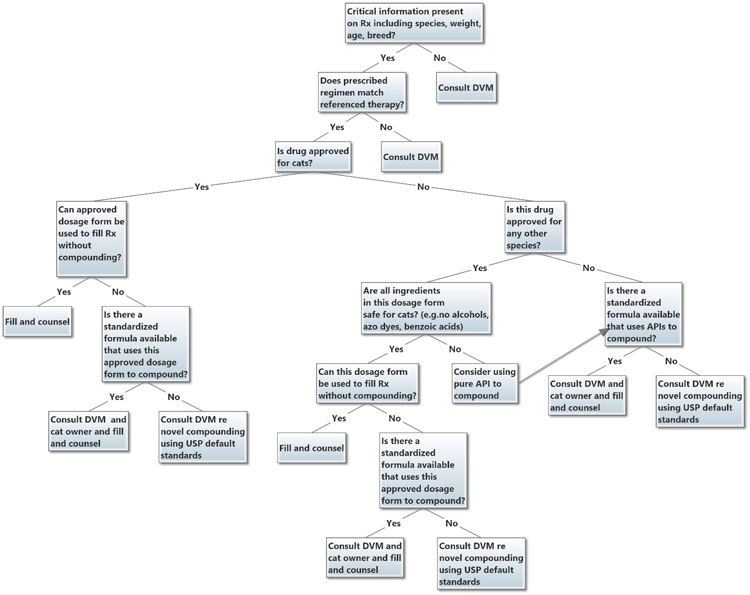

A general decision framework for evaluating and dispensing prescriptions for feline patients is outlined in Figure 1. Note that many decisions refer the pharmacist back to the prescribing veterinarian for a consultation to further clarify therapy or collaborate on a particular formulation to dispense.

Figure 1. Feline Prescription Due Diligence Decision Tree

Feline Hyperthyroidism

Feline hyperthyroidism is one of the most common disorders in older cats. It results in a variety of classic signs that initially mimic normal aging. Unfortunately, without treatment, hyperthyroidism can progress to severe morbidity and death. Fortunately, it can be managed easily with drug therapy.2

Hyperthyroidism involves oversecretion of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) by the thyroid gland. It usually is caused by non-neoplastic hyperplasia of thyroid glands, but it sometimes is caused by thyroid carcinoma. Middle-aged to older cats are affected most commonly (mean age at onset 13 years; range 4–22 years). The etiology is largely unknown, although some investigators have associated a decreased risk in Siamese and Himalayans, and a higher prevalence in cats fed a diet primarily of canned food, and households that use cat litter.3

The most commonly observed signs of feline hyperthyroidism are weight loss, polyphagia, vomiting, diarrhea, polydipsia, tachypnea, hyperactivity with nighttime vocalization, unkempt hair coat, and hyperkeratinization of nails. High perfusion of kidneys and resultant increased glomerular filtration rate may mask chronic kidney disease in older cats; treatment of hyperthyroidism may unmask this condition.

The prognosis for feline hyperthyroidism is excellent for uncomplicated disease with adherence to medical treatment. Prognosis is poor for thyroid carcinoma, although if it is caught early and treated with appropriately high doses of radioactive iodine, the long-term prognosis may be very good (i.e., extended survival). Unmasking of chronic renal disease from correction of hyperthyroidism worsens prognosis.

Treatment Options

Treatment options for feline hyperthyroidism include thyroidectomy, radioactive iodine ablation of the thyroid, and lifelong medical management.

Thyroidectomy is less commonly employed because of the risks of anesthesia and the fact that safer options—radioactive iodine in particular—are more widely available. Surgery also carries the risk of damage to the parathyroid glands with resultant hypocalcemia.

Ablation of the thyroid with radioactive iodine-131 (I-131) is available in most metropolitan areas. The procedure is common and generally curative, but it also is expensive and requires admission to a treatment center for several days. Some protocols require 2-week pretreatment with antithyroid medications to (1) determine whether treatment will unmask chronic renal failure and (2) estimate the dose of I-131 based on response. Owner adherence during this 2-week pretreatment regimen is critical to the success of radioactive iodine therapy.

Lifelong pharmacologic therapy is the most common treatment option. Although it is not curative, treatment with methimazole or carbimazole is convenient and relatively inexpensive. Propylthiouracil had been used to treat feline hyperthyroidism, but it no longer is recommended for use in cats because of a high incidence of autoimmune-mediated hemolytic anemia.

Methimazole. Methimazole is FDA-approved for the treatment of feline hyperthyroidism (Felimazole). It is available as small, film-coated tablets (2.5 mg and 5 mg). Although methimazole tablets approved for humans may be used off-label for the treatment of feline hyperthyroidism, the veterinary tablets tend to be better accepted by cats.

The usual dosage of methimazole per cat is 1.5–5 mg by mouth every 12–24 hours. The recommended starting dosage is 2.5 mg every 12 hours for 3 weeks; the dose then is titrated based on clinical response and serum T4 levels. Dose adjustments are made in increments of 1.25–5 mg. The dose may be titrated further every 3–6 months as needed to maintain control.

Many cat owners are unable to manage administration of methimazole tablets. Consequently, pharmacists often receive prescriptions for compounded oral liquid or transdermal gel dosage forms. Methimazole transdermal gel is compounded in concentrations ranging from 1.5 mg/0.1 mL to 5 mg/0.1 mL. The onset of effect is slower by the transdermal route than the oral route.4 The usual dosage is the same as for oral methimazole; dose adjustments are made in increments of 1.5–5 mg. The gel is applied to the hairless area near the tip of the inside of the ear (pinna). The pinna should be cleaned gently with a moist towel before the gel is applied. After application, the gel should be rubbed into the skin thoroughly to avoid oral ingestion from grooming. Caregivers should wear gloves when applying the gel and use alternate ears for application. Pharmacists should be aware (and make clients aware) that refrigeration may disrupt the integrity of pluronic lecithin organogel (PLO) vehicle.

The most common adverse effects of methimazole therapy are anorexia, vomiting, and soft stool. Oral dosage forms should be administered with food to minimize gastrointestinal upset. A hypersensitivity reaction that manifests as facial excoriations leads to discontinuation of therapy in approximately 3%–15% of cats.

Antithyroid medications can cause damage to the liver and bone marrow. Serum liver enzymes should be monitored to detect possible hepatopathy. Myasthenia gravis is a rare but serious complication of methimazole therapy and may be immune-mediated. Owners should report any unusual symptoms or changes in behavior to the veterinarian immediately.

Carbimazole. Carbimazole is a prodrug of methimazole. It is not approved in the United States, so dosage forms for cats (e.g., oral solution, transdermal gel) must be compounded using bulk substance.5 Dosage, titration, and cautions are the same as for methimazole.

Because carbimazole is a prodrug, it is not suitable for use in cats who do not tolerate therapy with methimazole.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

A follow-up visit usually is scheduled 2–3 weeks after antithyroid therapy is initiated. The visit includes a physical examination and laboratory tests (serum T4 level, complete blood count, chemistry panel). Once the cat is normalized, subsequent follow-up visits are scheduled every 3–6 months.

|

Client Counseling and Pharmacist Practice Tips: Feline Hyperthyroidism

Client Counseling

- Drug therapy can control hyperthyroidism in cats, but it does not cure the condition.

- Administer oral medications with food to minimize gastrointestinal upset.

- Wear gloves when applying transdermal gel. Alternate the ears used for application.

- Rub the transdermal gel into the skin thoroughly to avoid oral ingestion from grooming.

- Do not refrigerate transdermal gels.

- Stop administering the medication and contact the veterinarian as soon as possible if the cat develops sores or lesions on the face.

- Let the veterinarian know if the cat experiences loss of appetite, increased vomiting, or increased diarrhea during treatment.

- It is important to honor scheduled recheck appointments at the veterinary clinic, so the response to therapy can be evaluated and the cat can be monitored for adverse events.

- If the cat is being treated with antithyroid medication before radioactive iodine-131 therapy, it is very important to administer all doses as directed.

Practice Tips for Pharmacists

- Maintain stock of veterinary-approved methimazole tablets to facilitate administration and adherence.

- Do not switch dosage forms without consulting the prescribing veterinarian. Bioavailability of antithyroid drugs may change dramatically depending on the vehicle (aqueous or anhydrous), the solid dosage form, and the route of administration. Always ask the pet owner what dosage form the cat has been receiving.

- Dispense gloves or finger cots and calibrated dosing syringes for administration of transdermal gels.

- Include the date of scheduled recheck appointments on the prescription label and emphasize it during verbal counseling.

|

Feline Diabetes Mellitus

Depending on the population studied, feline diabetes mellitus occurs in anywhere from 1 in 400 cats to 1 in 50 cats.6,7 Recent evidence suggests that the prevalence is increasing because of an increase in the frequency of predisposing factors such as obesity and physical inactivity.8 Other known risk factors include age (older than 8 years), high-carbohydrate diet, gender (male neutered), breed (Burmese in some geographical locations including Australia and the United Kingdom), drug therapy (e.g., corticosteroids), and concurrent conditions such as infection, hyperthyroidism, and chronic renal insufficiency.9

Type 1 diabetes is rare in cats; most cats with diabetes (80%) have type 2 diabetes. It is caused by a combination of insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency secondary to β cell dysfunction. Clinical signs of diabetes in cats include polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, obesity with recent weight loss, lethargy, dehydration, poor hair coat, hepatomegaly, and neuropathy (hind limb weakness, difficulty jumping, or plantigrade posture). Cats do not typically develop diabetic cataracts (a common sequelae in dogs).

The prognosis is good to excellent in cats with no concurrent disease, assuming good owner adherence to therapy. In one study of 114 cats with diabetes, median survival time was 516 days, with 25% of cats living more than 1,420 days.10

It is not unusual for cats to go into spontaneous clinical remission within 1–4 months after treatment is initiated. Factors that may influence the likelihood of remission include early diagnosis, extent of β-cell function, carbohydrate content of the diet, and ability to maintain the blood glucose concentration within the normal range.

Treatment Options

The goals of therapy in cats with diabetes mellitus are to:

- Maintain blood glucose levels between 120 mg/dL and 300 mg/dL.

- Achieve clinical remission (if possible).

- Minimize clinical signs of polyuria and polydipsia.

- Avoid complications such as ketoacidosis and hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL).

- Avoid long-term sequelae such as neuropathy.

Cats with diabetes usually are not controlled as tightly as humans with diabetes are because of the risk of severe hypoglycemia.

Some cats diagnosed early with diabetes may respond well to dietary changes alone. The diet should be consistent regarding type of food, quantity of food, and timing of meals. Veterinarians generally recommend a diet of low-carbohydrate commercial canned food; for example, pate formulations are preferred over sliced food in gravy. Veterinarians also may prescribe a therapeutic feline diabetic diet (food available from veterinarians only).

Most cats require drug therapy (Table 1). Oral hypoglycemic agents often are not effective in cats, so insulin is the mainstay of treatment. The insulins used most frequently in cats are protamine zinc insulin, insulin glargine, and porcine insulin zinc suspension. The duration of action of Neutral Protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin (<12 hours) is too short to be useful in most cats with diabetes.

| Table 1. Drug Therapy for Feline Diabetes Mellitus |

| Drug |

Usual Dosage |

Dosage Forms |

| Glipizide |

2.5–5 mg by mouth every 12 hours |

Tablets approved for humans: 5 mg, 10 mg |

| Protamine zinc recombinant human insulin |

1 unit by subcutaneous injection every 12 hours, with or immediately after a meal |

Aqueous suspension approved for cats: 40 units/mL Available in 10-mL vials |

| Insulin glargine |

1 unit by subcutaneous injection every 12 hours, with or immediately after a meal |

Solution approved for humans: 100 units/mL |

| Porcine insulin zinc suspension |

1–2 units by subcutaneous injection every 12 hours, with or immediately after a meal |

Aqueous suspension approved for cats: 40 units/mL

Available in 10-mL vials and 2.7-mL cartridges for use with the VetPen insulin pen |

The initial insulin regimen is determined based on a blood glucose curve. The blood glucose curve can be created in the veterinary clinic or at home; it is preferable for it to be created at home because stress (e.g., visiting the veterinary clinic) can elevate blood glucose levels in cats significantly.

Protamine Zinc Insulin. A formulation of protamine zinc recombinant human insulin 40 units/mL is FDA-approved for use in cats (ProZINC). It is available in 10-mL vials. The vial should be rolled gently between the palms of the hands (not shaken) before a dose is withdrawn.

In most average-size cats, therapy is initiated at a dosage of 1 unit by subcutaneous injection every 12 hours, with or immediately after a meal. The initial dosage should not exceed 2 units every 12 hours, even in very large cats. Ideally, the nadir occurs approximately 9 hours after insulin injection with a blood glucose level ≥150 mg/dL. If the cat’s blood glucose level drops below 150 mg/dL at any point during the day, subsequent doses should be decreased by 0.5 units and the veterinarian should be notified. If low normal readings persist—or if the blood glucose level drops below 100 mg/dL—subsequent doses should be decreased by another 0.5 units and the veterinarian should be contacted immediately.

If the cat’s blood glucose level drops to 60 mg/dL or lower, the owner should administer corn syrup (e.g., Karo syrup) immediately. An amount equivalent to approximately 6 mL per 10 lb of body weight should be rubbed bit by bit on the cat’s gums or under its tongue to avoid aspiration. The owner also should notify the veterinarian or take the cat to a nearby emergency veterinary clinic immediately.

Cats that remain hyperglycemic after 7 days of insulin therapy should be evaluated by a veterinarian for dosage adjustment.

Protamine zinc insulin should be administered using U-40 syringes only. If U-40 syringes are not available, the dose must be multiplied by 2.5 to determine the correct dose volume for a U-100 syringe.

Insulin Glargine. Insulin glargine approved for humans (100 units/mL) is used off-label for the treatment of feline diabetes mellitus. It is available in 10-mL vials and 3-mL prefilled insulin pens. The dosing is the same as for protamine zinc insulin. Cats should not receive more than 3 units per dose (unless directed by a veterinarian).

It is possible to use insulin pens as multi-dose vials, especially for cases in which the 10-mL vial would expire before the contents could be used. Doses can be withdrawn through the septum using an insulin syringe.

Insulin glargine must maintain a pH of 4.0 to provide a long duration of action. The solution should not be diluted or mixed with other insulins.

Porcine Insulin Zinc Suspension. A formulation of porcine insulin zinc suspension 40 units/mL (Vetsulin) is FDA-approved for use in cats (and dogs). It is available in 10-mL vials as well as in 2.7-mL cartridges for use with the VetPen insulin pen. Insulin cartridges can be used as multi-dose vials by withdrawing doses through the septum using an insulin syringe. Both the vials and the cartridges must be shaken well before use until a homogeneous, uniformly milky suspension is obtained.

Porcine insulin zinc suspension has a relatively short duration of action, and control of clinical signs in cats tends to be poor. Use of this insulin generally is reserved for cats that do not have a satisfactory response to other insulins.

Therapy with porcine insulin zinc suspension is initiated at a dosage of 1–2 units by subcutaneous injection every 12 hours, with or immediately after a meal. Adjustments based on blood glucose levels are the same as for protamine zinc insulin and insulin glargine. Cats should not receive more than 3 units per dose (unless directed by a veterinarian).

Porcine insulin zinc suspension should be administered using U-40 syringes only. If U-40 syringes are not available, the dose must be multiplied by 2.5 to determine the correct dose volume for a U-100 syringe.

Glipizide. Glipizide tablets approved for humans may be used off-label for the treatment of feline diabetes mellitus. Glipizide has been associated with β-cell destruction and may lose efficacy over time. Use generally is reserved for situations in which the cat owner cannot or will not administer insulin but wants to consider alternatives to euthanasia.

Treatment with glipizide usually is initiated at a dosage of 2.5 mg by mouth every 12 hours with food. If response is not adequate after 2 weeks of therapy, the dosage can be increased to 5 mg every 12 hours.

Transdermal glipizide has been found to reduce blood glucose levels in normal cats but has not been studied in cats with diabetes.11

Monitoring and Follow-Up

Monitoring and follow-up during the first week of insulin therapy are critical to successful management of feline diabetes mellitus. The cat owner’s assessment of how the cat is feeling is as important as any blood or urine tests. Owners are expected to maintain a daily log of food intake, water intake, appetite, and insulin doses. They also must conduct periodic urine testing to watch for negative glucosuria (which could indicate diabetic remission or impending hypoglycemia) or positive ketonuria (which could indicate substantial hyperglycemia). Urine testing can be accomplished by immersing a test strip in the urine stream as the cat is urinating or by using a nonabsorbent substrate in the litter box (e.g., Styrofoam peanuts, aquarium gravel).

During weeks 2 to 4 of insulin therapy, owners should commence home blood glucose monitoring by spot-checking blood glucose 2–8 hours after a dose of insulin and immediately before the next dose. A blood glucose level <150 mg/dL may require a decrease in insulin dose or frequency as directed by the veterinarian. Owners should use a glucometer designed for pets (e.g., AlphaTRAK, iPet); these monitors are much more accurate in cats and require only 0.0003 mL of blood per sample. Only the marginal ear vein or a paw pad should be used for blood sampling. To prevent infection, sampling sites should be cleaned thoroughly before the lancet is inserted.

One month after insulin therapy is initiated, cats with diabetes should undergo a complete physical examination, weight check, and laboratory tests (complete blood count, serum chemistries, and serum fructosamine). Fructosamine reference ranges for glycemic control are similar to those for humans:

- <250 uMol/L = prolonged hypoglycemia.

- 300–350 uMol/L = excellent.

- 350–400 uMol/L = good.

- 400–450 uMol/L = fair.

- >450 uMol/L = poor.

Because feline hemoglobin is uniquely sensitive to oxidative injury, it usually is not used as a reliable indicator of glycemic control in cats.

For cats that do not go into remission, veterinarians will schedule recheck appointments every 3–6 months for repeat physical examination, weight check, and laboratory tests (complete blood count, serum chemistries, serum fructosamine).

It is important that owners watch for signs of hypoglycemia. Cats with low blood glucose may exhibit lethargy or dullness, restlessness, anxiety or other behavioral changes, weakness, difficulty standing or ataxia, tremors, seizures, and coma that could proceed to death. Cats are unable to sweat, so caregivers should be warned that diaphoresis is not a clinical sign of hypoglycemia in cats.

|

Client Counseling and Pharmacist Practice Tips: Feline Diabetes Mellitus

Client Counseling

- Administer insulin only after meals, not before. Do not change the dose unless directed to do so by a veterinarian.

- Be sure to obtain refills of insulin several days before the supply will run out to avoid lapses in therapy.

- Gently roll vials of protamine zinc insulin between the palms of the hands before use; do not shake.

- Shake vials and cartridges of porcine insulin zinc suspension (Vetsulin) before use.

- Record administration of insulin doses and results of blood and urine glucose monitoring in a journal or smartphone application. If there are multiple caregivers in a household, the documentation system should allow for communication among caregivers, especially to avoid double-dosing.

- Report changes in the cat’s appetite, water consumption, or activity to the veterinarian.

- Use the marginal ear vein or paw pads to obtain blood samples for glucose testing. The site should be cleaned thoroughly before the sample is taken to prevent infection.

- Be alert for signs of hypoglycemia in cats (lethargy or dullness, restlessness, anxiety or other behavioral changes, weakness, difficulty standing or ataxia, tremors, seizures, coma).

- Be sure to visit the veterinarian for all scheduled appointments so that laboratory testing and potential dosage adjustments can occur.

- Store insulin according to manufacturer recommendations both before and during use.

Practice Tips for Pharmacists

- Do not substitute insulins without consulting the prescribing veterinarian.

- Maintain inventories of insulin approved for use in cats and U-40 insulin syringes.

- Maintain inventories of human insulins used commonly in cats, ideally in 3-mL vials or pens to avoid waste.

- Maintain inventories of U-100 insulin syringes with half-unit demarcations (insulin dose adjustments in cats usually occur in 0.5-unit increments).

- Demonstrate how to measure insulin doses accurately in a syringe, especially for 0.5-unit doses.

- Maintain inventories of blood glucose monitors designed for pets (e.g., AlphaTRAK, iPet) and associated supplies such as lancets and test strips.

- Maintain quantities of corn syrup or dextrose 50% for emergency administration to hypoglycemic cats; demonstrate application of these solutions to the gums of the pet.

- Provide access to caregiver information resources (e.g., videos on how to administer insulin to cats and check blood and urine glucose) and applications for tracking insulin doses, test results, diet, activity, and other information.

|

Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the most commonly diagnosed cardiac disease in cats. It accounts for 85%–90% of all cases of cardiomegaly. Restrictive cardiomyopathy occurs in a small number of cats (10% of cases). Dilated cardiomyopathy has been uncommon in cats since the 1980s, when it was linked to dietary taurine deficiency.

Although cats of any age may be affected, feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy typically is diagnosed in cats 5–7 years of age (range 6 months to 16 years). A definitive cause has not been determined, but there appears to be a genetic component. Autosomal dominant inheritance has been identified in Maine Coon, Persian, Ragdoll, and American Shorthair breeds. High incidence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy also is seen in British Shorthairs, Norwegian Forest Cats, Siamese, Sphynx, Scottish Folds, Bengals, and Rex. Male cats of all breeds are over-represented (75%).

Clinical signs of feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy vary widely. Many cats are completely asymptomatic until they are diagnosed or experience sudden death. When signs are present, they may include dyspnea and open mouthed-breathing, exercise intolerance, anorexia, tachypnea (>30 breaths/min), vomiting, collapse, and posterior paralysis and dragging hind limbs (from saddle thrombus at the bifurcation of the aorta down the rear legs).

The prognosis for cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy depends in large part on the severity of disease at diagnosis. Retrospective medical record reviews have drawn similar conclusions regarding survival time.12,13 Generally, cats with a resting heart rate <200 bpm at diagnosis lived longer than those with a resting heart rate >200 bpm. Median survival time for asymptomatic cats was 3 years. Median survival after a thromboembolism was 6 months, and median survival for cats diagnosed with heart failure was 18 months.

Treatment Options

The goals of treatment are to enhance ventricular filling, relieve congestion, control arrhythmias (resting heart rate <200 bpm), minimize ischemia, and prevent thromboembolism. Drug therapy relies heavily on medications approved for use in humans. Although the principles of therapy closely follow those for humans with heart disease, variations in feline drug metabolism and disposition result in some notable differences. For example, the frequency of administration of diltiazem depends entirely on the selected human-approved dosage form.

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors. Enalapril and benazepril approved for humans are used off-label for the treatment of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Table 2).

Enalapril can decrease the glomerular filtration rate, so renal function should be monitored closely in treated cats. The dose should be reduced by 50% in cats with renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >2.3 mg/dL). Polyuria, polydipsia, and vomiting may indicate renal insufficiency.

Benazepril increases the glomerular filtration rate. It is approved outside the United States for nephroprotection in cats. Benazepril may be considered as an alternative to enalapril in cats with serum creatinine >2.3 mg/dL.

Diuretics. The diuretics used most commonly in cats are furosemide, spironolactone, and hydrochlorothiazide (Table 2). Furosemide tablets (12.5 mg and 50 mg) are FDA-approved for use in cats. Hydrochlorothiazide and spironolactone approved for humans are used off-label. Sprinolactone is not used as often because of equivocal evidence of efficacy and a high incidence of adverse effects. Some cats experience severe immune-mediated hypersensitivity to spironolactone, manifesting as facial ulcerations or excoriations; therapy should be discontinued if hypersensitivity is suspected.14

Antithrombotic Drugs. Antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel) and anticoagulants (dalteparin, enoxaparin, warfarin) are used for the prevention of thromboembolism in cats (Table 2).

| Table 2. Drug Therapy for Feline Cardiomyopathy |

| Drug |

Dosage* |

| Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors |

| Enalapril |

0.25–0.5 mg/kg every 12–24 hours |

| Benazepril |

0.25–0.5 mg/kg every 12–24 hours |

| Diuretics |

| Furosemide |

1–2 mg/kg every 8–24 hours (titrate to lowest effective dose) |

| Spironolactone |

0.5–1 mg/kg every 12–24 hours |

| Hydrochlorothiazide |

0.5–2 mg/kg every 12–48 hours (titrate to lowest effective dose) |

| Antithrombotic Drugs |

| Aspirin |

5 mg every 24 hours or 20–40 mg every 72 hours |

| Clopidogrel |

75 mg loading dose; then 18.75 every 24 hours or 2–4 mg/kg every 24 hours |

| Dalteparin |

100–150 units/kg by subcutaneous injection every 6–24 hours (no consensus on best dose or frequency) |

| Enoxaparin |

1–1.5 mg/kg by subcutaneous injection every 6–12 hours |

| Warfarin |

0.1–0.2 mg every 24 hours |

| Antiarrhythmic Agents |

| Atenolol |

6.25–12.5 mg every 12–24 hours |

| Diltiazem immediate release |

1.5–2.5 mg/kg every 8 hours |

| Diltiazem extended release |

30–60 mg every 12 hours |

| Diltiazem controlled delivery |

10 mg/kg every 24 hours |

| Inotrope |

| Pimobendan |

0.25 mg/kg every 8–12 hours |

| *All doses are administered by mouth unless stated otherwise. |

Aspirin usually must be compounded to achieve the doses employed in cats. (One possible dosing regimen calls for fractions of low-dose aspirin tablets to be administered every 72 hours.) Aspirin toxicity in cats can cause gastric ulceration and profound systemic acidosis; owners should contact the veterinarian if they observe symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding or distress in the cat (e.g., black, tarry feces; anorexia; vomiting).

Clopidogrel is the antiplatelet agent of choice in cats. However, it also must be compounded for cats that require doses <18.75 mg.

Warfarin is not used often in cats. Like aspirin, it must be compounded to achieve the required dose; it also carries the risk of initial procoagulation, needs frequent monitoring, and interacts with many other drugs. Dalteparin and enoxaparin approved for humans are the primary anticoagulants for prevention of thromboembolism in cats. Enoxaparin also may be effective in decreasing the incidence of future clots. Both dalteparin and enoxaparin are best dispensed in a multi-dose vial and administered with U-100 insulin syringe to achieve small dose volumes accurately, avoid loss of drug in hub space, and minimize bleeding.

Antiarrhythmic Agents. Atenolol and diltiazem approved for humans are used off-label for the treatment of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Table 2).

The dose of atenolol may be titrated upward slowly to avoid adverse effects such as bradycardia, lethargy, and depression.

Diltiazem may be prescribed as regular (immediate-release) tablets, controlled-delivery capsules, or extended-release tablets or capsules. The choice of dosage form depends on the desired frequency of administration. Capsules that provide a long duration of action contain beads (controlled delivery) or tablets (extended release); the contents of either can be used to provide smaller doses for cats. For example, the beads from a 120-mg, controlled-delivery capsule can be used to fill the small end of a size #4 gelatin capsule to achieve approximately 45 mg of controlled delivery diltiazem per dose (the dose for an average-sized cat). Each of the tablets in an extended-release capsule contains diltiazem in an extended-release wax matrix formulation; caregivers may be instructed to open the capsule and administer a full tablet or half tablet every 12 hours. Pharmacists should take care not to confuse prescriptions for 30-mg regular tablets with prescriptions for 30-mg extended-release tablets (i.e., the dose achieved by opening the extended-release capsule and administering half of one of the inner tablets). Pharmacists also should counsel owners not to crush the tablets or beads before dose administration, to preserve the sustained-release effect of these dosage forms

Inotrope. As discussed in greater detail in Module 7 (“Providing Pharmaceutical Care and Products for Dogs”), pimobendan (Table 2) is a veterinary-only drug approved for the treatment of congestive heart failure in dogs (Vetmedin).15 Pimobendan sometimes is used off-label in cats for the treatment of treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. However, pimobendan is supplied as relatively large, liver-flavored chewable tablets. Owners may find it difficult to administer pimobendan to cats in its approved dosage form.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

Caregivers should monitor cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy for signs of dyspnea, lethargy, weakness, or posterior paralysis. Posterior paralysis indicates a thromboembolism at the trifurcation of the femoral artery (arteries to hind limbs and tail) and requires emergency treatment (or possibly euthanasia).

Veterinarians usually perform a repeat electrocardiogram at 4 months to assess the efficacy of treatment. Annual veterinarian visits are recommended to assess treatment efficacy and disease progression.

Owners may be directed to monitor the cat’s resting heart rate. Measurements ideally should be taken from the femoral artery, which is best palpated on the cat’s inner thigh. Alternatively, the heart rate may be counted by gently palpating the chest wall beneath the axillae. Owners may find it helpful to purchase an inexpensive over-the-counter stethoscope and obtain instruction in auscultation from the veterinary team.

|

Client Counseling and Pharmacist Practice Tips: Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Client Counseling

- Honor all recheck appointments. Ongoing physical examination and laboratory testing are critical to the success of the therapy.

- Medication administration should result in as little stress as possible. Unpalatable tablets may be concealed inside an empty gelatin capsule to facilitate administration. Report any difficulties to the veterinarian and pharmacist.

Practice Tips for Pharmacists

- Maintain inventories of difficult-to-find drugs and devices used to treat feline cardiomyopathies (e.g., compounded 5-mg aspirin capsules, dalteparin and enoxaparin injections, administration syringes).

- Do not substitute dosage forms without consulting the prescribing veterinarian.

- Bioavailability of many drugs increases significantly when converting from solid oral dosage forms to liquids.

- Consider compounding smaller or more palatable dosage forms as needed to reduce a cat’s medication stress.

- Confirm that clients who purchase aspirin for use in cats have selected a low dose (81 mg) product.

- Demonstrate any required manipulation of dosage forms (e.g., splitting tablets, opening capsules, withdrawing volumes of oral liquids or injections).

- Develop or provide client education materials with instructions for manipulating diltiazem dosage forms—for example, how to open extended-release capsules to expose inner tablets and how to repackage beads from extended-release capsules into smaller doses.

- Know and be able to demonstrate how to measure resting heart rate in cats (femoral artery, axillary arteries).

|

Feline Asthma (Feline Chronic Bronchitis)

Feline asthma—also called feline chronic bronchitis—affects approximately 1% of cats in U.S. households. It is associated with substantial morbidity and occasional mortality.

Feline asthma is the result of a variety of genetic and environmental factors that lead to a type I hypersensitivity to airborne allergens. The pathophysiology is similar to asthma in humans; it is characterized by eosinophilic airway inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, bronchoconstriction (in response to both allergenic and non-allergenic stimuli), and airway remodeling (permanent architectural changes in the lungs). These pathologic changes lead to clinical signs of cough, wheeze, and expiratory respiratory distress. The term “asthma” usually is reserved for a clinical diagnosis of idiopathic airway disease characterized by a cough of more than 2 months’ duration. Most veterinarians prefer to use the term “allergic bronchitis” for cats that respond to the removal of known triggers from their environment.

Feline asthma typically is seen in young to middle-aged cats (median age 4 years; range 1–15 years). A strong genetic predisposition exists in Siamese and Himalayan cats.

Veterinarians now believe that many cats previously diagnosed with asthma or allergic bronchitis actually were experiencing heartworm-associated respiratory disease (HARD). Feline heartworm disease is beyond the scope of this activity; interested participants are encouraged to visit www.capcvet.org for further information.

Feline asthma is considered incurable. The prognosis depends on the severity of disease, but most cats survive for years with appropriate lifelong treatment. It is important for cat owners to be educated thoroughly about their pet’s condition, including:

- Warning signs of asthma attacks.

- Factors that may trigger asthma attacks.

- How to manage acute asthma attacks.

- How to administer all drugs and use all devices included in the treatment plan.

Treatment Options

Treatment strategies for feline asthma encompass environmental measures and pharmacologic therapy. Ideally, known or potential triggers (e.g., pollen, perfumes, cigarette smoke, dusty cat litter) should be removed from the environment, and air filtration or purification systems should be installed to contain airborne particles. Because not all triggers can be identified, a primary goal of pharmacologic therapy is symptomatic relief through use of anti-inflammatory agents and bronchodilators delivered orally, by injection, or by inhalation. Delivery of drugs directly to the lungs by inhalation avoids systemic adverse effects but can be quite expensive. Systemic therapy is inexpensive but risks significant systemic adverse effects.

Principles of therapy in feline asthma are similar to those for humans, with the significant exception of leukotriene inhibitors. Leukotrienes do not appear to be significant contributors to feline asthma; consequently, leukotriene inhibitors are not used to treat feline asthma.16 Serotonin and histamine release following mast cell degranulation are responsible for clinical signs in humans with asthma, but antiserotonergic agents such as cyproheptadine and antihistamines such as cetirizine have proven to be of little to no benefit in the treatment of feline asthma.17,18

Anti-Inflammatory Agents. The anti-inflammatory agents used most commonly for the treatment of feline asthma are prednisolone, fluticasone, and cyclosporine (Table 3).

Systemic corticosteroid therapy traditionally has been the mainstay of therapy for feline asthma. Cats generally require therapy with prednisolone (not prednisone) because they do not metabolize prednisone to prednisolone efficiently. Therapy is initiated at a dosage of 1–2 mg/kg by mouth every 12 hours for 5–7 days. If clinical improvement is noted, the dose is tapered gradually over 2–3 months. Owners should not be alarmed if cats treated with prednisolone exhibit increased urination, thirst, and hunger. However, chronic corticosteroid therapy is a risk factor for diabetes mellitus in cats, so ongoing monitoring is important.

Fluticasone currently is considered to be the anti-inflammatory therapy of choice for feline asthma because of the relatively low incidence of systemic adverse effects. Fluticasone inhalation aerosol approved for humans is used off-label in cats. All of the available strengths (44 µg, 110 µg, 220 µg) have been shown to be equally effective19; consequently, many veterinarians initiate therapy with the 44-µg inhaler (1–2 actuations every 12 hours) to minimize expense. It is customary to administer prednisolone 1–2 mg/kg by mouth every 12 hours for 10–14 days when therapy is initiated, until fluticasone reaches maximal effect. A dose of albuterol may be administered once daily just before fluticasone administration to increase airway exposure.

Cyclosporine is FDA-approved for the control of allergic dermatitis in cats as a 100 mg/mL oral solution (Atopica). It is used off-label for the treatment of feline asthma. A capsule formulation of cyclosporine is FDA-approved for use in dogs (Atopica) and sometimes is used off-label in cats. The usual dosage is 10 mg/kg by mouth every 12 hours. Cyclosporine is effective in limiting airway hyperresponsiveness and remodeling (cytological and histological alterations), but it does not inhibit not mast cell degranulation.20

Bronchodilators. Short-acting and long-acting β2 agonists—albuterol, terbutaline, and salmeterol—are used most commonly as bronchodilators for the treatment of feline asthma are (Table 3). Theophylline also may be prescribed by some veterinarians, but it provides less potent bronchodilation compared with β2 agonists.

| Table 3. Drug Therapy for Feline Asthma |

| Drug |

Usual Dosage |

| Anti-Inflammatory Agents |

| Prednisolone |

1–2 mg/kg by mouth every 12 hours for 5–7 days; taper gradually over 2–3 months if clinical improvement is noted |

| Fluticasone |

1–2 actuations every 12 hours |

| Cyclosporine |

10 mg/kg by mouth every 12 hours |

| Bronchodilators |

| Terbutaline |

Oral: 0.1–0.2 mg/kg every 8–12 hours

Subcutaneous or intramuscular injection: 0.01 mg/kg for severe asthma attacks |

| Albuterol |

1–2 puffs every 30 minutes up to 4–6 hours for asthma attacks |

| Salmeterol |

1–2 puffs every 12 hours |

| Theophylline |

Regular release: 4 mg/kg by mouth every 8–12 hours

Extended release: 25 mg/kg by mouth every 24 hours |

Acute asthma attacks must be treated immediately to avoid risk of death and decrease ongoing fibrosis of the lungs. Albuterol approved for humans is the bronchodilator of choice for rescue treatment of acute asthma attacks in cats. The onset of effect occurs within 1–5 minutes. Albuterol is available as a racemic mixture; the S-enantiomer may cause airway hyperreactivity. Chronic use of albuterol may result in tolerance over time.

Terbutaline approved for humans is used off-label for the treatment of feline asthma. The onset of action when administered by mouth is 15–30 minutes; oral therapy is indicated primarily for the treatment of severe asthma in cats when inhaled albuterol therapy is not feasible. Terbutaline also may be administered by subcutaneous or intramuscular injection during severe attacks.

The long-acting β2 agonist salmeterol approved for humans is used off-label for the treatment of feline asthma. It is most suitable as chronic long-term therapy for severe disease, in combination with fluticasone. Salmeterol is associated with significant decrease in functional and inflammatory parameters.21 It produces less airway hyperreactivity than albuterol does.

Theophylline approved for humans is used off-label to treat cats with asthma. It is available in immediate-release and extended-release formulations; the extended-release formulations have poor oral availability in cats. Adverse effects of theophylline therapy include tachyarrhythmias, increased gastric acid secretion, and central nervous system stimulation. Theophylline also interacts with a large number of medications.

Metered-Dose Inhalers. The onset of action for inhaled drugs is significantly faster than for drugs administered by oral or injectable routes. Still, pharmacists may be surprised to learn that metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) are used commonly in cats, just as they are in humans. MDIs allow high concentrations of drugs to be delivered directly to the lungs, thereby avoiding or minimizing systemic adverse effects.

Because cats cannot be trained to inhale deeply upon actuation of the inhaler, spacers and face masks must be used. Spacers designed for humans can be adapted for use in cats by attaching a feline anesthesia mask to the end opposite the MDI; the AeroKat spacer and mask is designed specifically for use in cats.

Caregivers are instructed to shake the MDI well prior to use, insert it into the spacer, place a hand over the face mask, and actuate two puffs of medication into the spacer before applying the mask to the cat’s face. This avoids startling or intimidating the cat with the hissing sound that the MDI makes when actuated. The caregiver should hold the mask to the cat’s face until the cat has taken 7–10 breaths. The AeroKat has a visible flange that moves back and forth as the cat takes breaths, allowing the caregiver to count breaths.

Most cats tolerate the inhalation procedure very well, especially if it is associated with some sort of reward (food treats or increased petting). An effective acclimation routine has been suggested by a veterinarian specializing in feline therapy22:

Allow cat to get used to the device over several days letting it investigate it (e.g., leaving it by food bowl).

Reward (praise, food, catnip, stroking) fearless approaches to device and start placing it near cat’s face.

Practice with the mask over the cat’s face without anything in the chamber. Pre-load the chamber with a

puff of albuterol (in addition to the dose required). Make sure the mask is placed snugly over the muzzle

for 4–6 breaths.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

Cats with asthma typically are re-evaluated every 3–6 months to detect disease progression. Cats with severe lung disease may require follow-up chest radiographs.

Veterinarians also will perform weight checks on obese cats. Obesity can worsen feline asthma; obese cats will be started on a prescribed weight loss plan.

Owners of cats with asthma should keep a disease management log to record the details of treatment, frequency and duration of asthma attacks, suspected triggers, and other observations.

Cats treated with oral or systemic bronchodilators should be monitored for tachycardia and arrhythmias. Any cat that experiences acute wheezing or respiratory distress should be evaluated immediately by a veterinarian.

|

Client Counseling and Pharmacist Practice Tips: Feline Asthma

Client Counseling

- Honor all recheck appointments. Ongoing physical examination is important for detecting disease progression

- Avoid household use of products that are likely to trigger asthma attacks (e.g., perfumes, cigarette smoke, dusty cat litter, aerosol sprays).

- Inhaled albuterol should be used only for the treatment of acute asthma attacks, or once daily before a dose of fluticasone (if directed to do so by the veterinarian). It is not suitable and should not be used for chronic treatment of asthma.

- Maintain a disease management log with details about medications administered, frequency and duration of asthma attacks, suspected triggers, and other observations.

Practice Tips for Pharmacists

- Maintain inventories of difficult-to-find drugs and devices used to treat feline asthma, such as feline spacers and masks, metered-dose inhalers for albuterol and corticosteroids, terbutaline injection for rescue, and cat-friendly oral dosage forms of prednisolone, cyclosporine, and terbutaline (free of alcohol and dyes, appropriately flavored, appropriate concentration).

- Do not substitute dosage forms without consulting the prescribing veterinarian.

- Bioavailability of many drugs increases significantly when converting from solid oral dosage forms to liquids.

- Review the elements of a successful inhalation therapy acclimation routine.

- Demonstrate the assembly, use, cleaning, and storage of metered-dose inhalers and spacers.

- Be able to demonstrate how to administer emergency drugs by the subcutaneous route in cats.

- Develop or provide client education materials with instructions for assembling, loading, cleaning, and storing metered-dose inhalers and spacers used in cats. Include sources for replacement parts.

- Develop or provide client education materials with instructions for administering inhaled medications to cats.

- Provide access to caregiver information resources that depict the clinical signs of asthma in cats (e.g., videos that differentiate cough from regurgitation or vomiting in cats).

|

Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease

Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) is an umbrella term covering several common conditions that can affect the cat's urinary bladder or urethra. These conditions include:

- Feline idiopathic cystitis, the most common cause of FLUTD in cats younger than 10 years of age. Approximately two-thirds of cats with FLUTD have feline idiopathic cystitis.

- Uroliths, stones residing in the urinary bladder or urethra that may or may not cause obstruction.

- Urethral obstruction, caused by a urolith or urethral plug that has lodged in the urethra and prevents the cat from urinating. Urethral obstruction is a medical emergency.

- Urinary tract infection, which results in characteristic clinical and behavioral signs such as straining to urinate, frequent or prolonged attempts to urinate, crying out while urinating, excessive licking of the genital area, urinating outside the litter box, and blood in the urine.

A working diagnosis of FLUTD often is applied until a definitive diagnosis can be made.

FLUTD occurs in all breeds of cats. Long-haired cats may have an elevated risk.23 There is no correlation with sex, although a perception exists in the veterinary community that males are over-represented for urinary obstruction because of the anatomical orientation of the male urethra.

Treatment of FLUTD depends on causative factors, presence of bacterial infection (only 1%–3% of cases), chronicity (i.e., acute or recurrent), and presence of or risk for urethral obstruction. In general, therapy for obstructive FLUTD is surgical and therapy for non-obstructive FLUTD is pharmacological. Specific pharmacologic therapy is selected based on the causative condition; if the etiology cannot be determined, medical therapy is multimodal.

Environmental factors—including stress as defined by the cat—can be triggers for idiopathic lower urinary tract issues. Environmental enrichment or modification to relieve boredom and remove stressors (multimodal environmental modification, abbreviated as MEMO) commonly is employed before or concurrently with pharmacological therapy. Specific measures include:

- Using multiple litter boxes in multiple-cat households (one litter box per cat, plus one additional box).

- Providing toys and other forms of enrichment such as scratching posts and perches.

- Minimizing disruption and stress introduced by travel, visitors, other animals, and other stressors.

- Providing adequate space for escape from stress.

Urethral obstruction from stones or plugs is a life-threatening emergency that requires surgical intervention. Owners of cats with feline idiopathic cystitis must be vigilant in monitoring for signs of possible obstruction. Cats that exhibit distress and fail to produce urine after multiple attempts to urinate should be evaluated by a veterinarian immediately.

The prognosis for FLUTD depends on whether obstruction is present. In the absence of obstruction, symptoms of hematuria, dysuria, and pollakiuria usually are self-limiting and resolve over 4–7 days. However, they are likely to recur in cats with idiopathic cystitis. Cats with uroliths may be at increased risk for recurrence, depending on factors such as cat breed, urolith composition, and owner adherence to recommended dietary changes.

Treatment Options

Treatment of non-obstructive FLUTD is directed at increasing hydration, providing adequate analgesia, decreasing sympathetic nervous outflow (to relieve spasms of the bladder and urethra), and decreasing the cat’s response to stress with antianxiety medication and environmental modification. Very few of the preferred drug therapies are approved for use in cats; owners often must obtain medication from a community pharmacy, and pharmacists frequently need to compound formulations that provide doses suitable for cats.

It is very important for pharmacists to note that many urinary antiseptics and analgesics commonly used in humans are extremely toxic to cats. In particular, methenamine, methylene blue, and phenazopyridine should never be used in cats.

Drugs Used to Reduce Stress. Historically, veterinarians prescribed amitriptyline approved for humans off-label for treatment of severe, recurrent feline idiopathic cystitis in cats (Table 4), based on good results in humans with interstitial cystitis. However, in a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trial designed to evaluate short-term efficacy of amitriptyline in cats with feline idiopathic cystitis, amitriptyline did not reduce clinical signs, and the incidence of recurrence was higher in treated cats than cats that received placebo.24 Amitriptyline is a very bitter drug that is difficult to administer to cats. Common adverse effects include weight gain, urine retention, urolith formation, urinary tract infection, and hepatic enzyme elevation. Although some veterinarians still recommend amitriptyline for feline idiopathic cystitis, its value remains unproven.

Fluoxetine (Table 4) currently is the antianxiety agent of choice for cats. Cats usually are treated off-label with fluoxetine approved for humans. Owners should be aware that efficacy may not be fully apparent for as long as 8 weeks after fluoxetine therapy is initiated. Cats treated with fluoxetine may exhibit behavior changes (e.g., anxiety, irritability, sleep disturbances), anorexia, diarrhea, and changes in elimination patterns.

Analgesics. Butorphanol and buprenorphine (Table 4) are used most commonly for analgesia in cats. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is not recommended. Robenacoxib (Onsior) is the only NSAID that is FDA-approved for use in cats, and it is not approved for long-term therapy. No controlled trials support the safety and efficacy of NSAIDs administered chronically in cats. Although meloxicam is FDA-approved for use as an analgesic in cats, meloxicam did not improve clinical signs in cats with obstructive disease after 5 days of therapy.25 Meloxicam also has been reported to cause sterile hemorrhagic cystitis in humans and rodents.

Butorphanol tablets (1 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg) that are FDA-approved for use in dogs as a cough suppressant (Torbutrol) may be used off-label for analgesia in cats. However, butorphanol has a very short duration of action (1–2 hours), and there are no controlled trials demonstrating safety or efficacy in cats. Butorphanol is a Schedule IV controlled substance. Adverse effects include sedation, ataxia, anorexia, and diarrhea.

Buprenorphine is administered into the side of the cat’s mouth for buccal (transdermal) absorption. In cats, buccal administration has been shown to be as effective as intravenous administration.26 Buprenorphine injection (1.8 mg/mL) is FDA-approved for the control of postoperative pain in cats (Simbadol). It is a Schedule III controlled substance, and use is restricted to veterinary clinics. Buprenorphine injection approved for humans (0.3 mg/mL) may be prescribed off-label for cat owners to administer at home. Common adverse effects include sedation and respiratory depression.

Antispasmodics. Prazosin and phenoxybenzamine approved for humans have been used off-label for the treatment of FLUTD in cats (Table 4). Both drugs must be compounded for use in cats.

| Table 4. Drug Therapy for Non-obstructive Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease |

| Drug |

Dosage |

| Drugs Used to Reduce Stress |

| Amitriptyline |

5–12.5 mg by mouth every 12–24 hours |

| Fluoxetine |

0.5–1 mg/kg by mouth once daily |

| Analgesics |

| Butorphanol |

0.2–0.4 mg/kg by mouth every 8 hours for 1–3 days |

| Buprenorphine |

0.01–0.03 mg/kg administered buccally every 8 hours for 1–3 days |

| Antispasmodics |

| Prazosin |

0.25–1 mg by mouth every 8–24 hours for 5–7 days for acute urethral spasm |

| Phenoxybenzamine |

0.5 mg/kg by mouth every 12 hours |

Little data are available to support the use of either drug. No controlled trials have examined phenoxybenzamine treatment in cats. The efficacy of prazosin was questionable in one controlled trial.27

Common adverse effects of therapy with either prazosin or phenoxybenzamine include hypotension, dizziness, ataxia, and inappetance. Prazosin is less specific than phenoxybenzamine; increased systemic effects may be useful for decreasing sympathetic nervous system activation in cats.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

Veterinarians will perform a recheck urinalysis approximately 5 to 7 days after therapy is initiated to evaluate hematuria, pH, crystalluria, and possibly bacteriuria, depending on causative factors.

Cats that continue to experience urethral obstruction despite proper medical and dietary management may be candidates for a surgical procedure known as perineal urethrostomy. Much of the penis and the narrow portion of the urethra are removed, leaving a wider opening for urinating and passing stones. This surgery is considered to be a salvage procedure; with measures such as increased water in the diet and environmental modification to address stressors, the procedure can be avoided in many cats.

|

Client Counseling and Pharmacist Practice Tips: Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease

Client Counseling

- Cats with urinary tract disease that exhibit signs of possible obstruction—such as distress and fail to produce urine after multiple attempts to urinate—should be evaluated by a veterinarian immediately.

- Do not administer products intended for the treatment of human cystitis or urinary tract discomfort to cats. Specifically, phenazopyridine, methylene blue, and methenamine are toxic to cats and must not be used.

- Provide plenty of clean, fresh water for the cat at all times. Offer at least one water bowl option that is not placed near the food bowl.

- Some cats are attracted to moving water. Consider providing a pet water fountain to encourage drinking.

- Contact the veterinarian if a cat treated with prazosin or phenoxybenzamine exhibits signs such as dizziness, lack of muscle coordination, or loss of appetite.

- In households with more than cat, provide one litter box per cat plus one additional box.

- Enrich the cat’s environments with items such as toys, scratching posts, and perches.

- Minimize possible stress caused by factors such as travel, visitors, and other animals.

- Provide adequate space for the cat to escape from stress.

Pharmacist Practice Tips

- Recognize signs and symptoms of feline lower urinary tract disease and direct cat owners to seek veterinary evaluation for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

- Maintain inventories of analgesics (buprenorphine, butorphanol) and antispasmodics (prazosin, phenoxybenzamine) in cat-friendly dosage forms. Liquid formulations may increase water intake.

- Show cat owners how to encapsulate doses of unpalatable tablets inside an empty gelatin capsule to mask the taste before administering to cats.

- Post notices near human nonprescription products warning that phenazopyridine and NSAIDs are toxic to cats.

|

References

- American Pet Products Association. Pet industry market size & ownership statistics. http://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp. Accessed October 31, 2016.

- Daminet S. Best practices for the pharmacological management of hyperthyroid cats with antithyroid drugs. J Small An Pract. 2014; 54(12):667-71.

- Mooney CT. Pathogenesis of feline hyperthyroidism. J Feline Med Surg. 2002;4(3):167-9.

- Lécuyer M, Prini S, Dunn ME, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of transdermal methimazole in the treatment of feline hyperthyroidism. Can Vet J. 2006;47(2):131-5.

- Buijtels JJ, Kurvers IA, Galac S, et al. Transdermal carbimazole for the treatment of feline hyperthyroidism. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd. 2006;131(13):478-82.

- Baral RM, Rand JS, Catt MJ, et al. Prevalence of feline diabetes mellitus in a feline private practice. Abstract 221. J Vet Intern Med. 2003:17:433-4.

- Panciera DL, Thomas CB, Eicker SW, et al. Epizootiological patterns of diabetes mellitus in cats: 333 cases (1980–1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;197(11):1504–8.

- Prahl A, Guptill L, Glickman NW, et al. Time trends and risk factors for diabetes mellitus in cats presented to veterinarian teaching hospitals. J Feline Med Surg. 2007;9(5):351-8.

- Rand JS, Fleeman LM, Farrow HA, et al. Canine and feline diabetes mellitus: nature or nurture? J Nutr. 2004;134(8 Suppl):2072S-80S.

- Callegari C, Mercuriali E, Hafner M, et al. Survival time and prognostic factors in cats with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus: 114 cases (2000-2009). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;243(1):91-5.

- Bennett N, Papich MG, Hoenig M, et al. Evaluation of transdermal application of glipizide in a pluronic lecithin gel to healthy cats. Am J Vet Res. 2005;66(4):581-8.

- Rush JE, Freeman LM, Fenollosa NK, et al. Population and survival characteristics of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: 260 cases (1990-1999). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;220(2):202-7.

- Atkins CE, Gallo AM, Kurzman ID, et al. Risk factors, clinical signs, and survival in cats with a clinical diagnosis of idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: 74 cases (1985-1989). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;201(4):613-8.

- MacDonald KA, Kittleson MD, Kass PH, et al. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and left ventricular mass in Maine Coon cats with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22(2):335–41.

- Reina-Doreste Y, Stern JA, Keene BW, et al. Case-control study of the effects of pimobendan on survival time in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;245(5):534-9.

- Norris CR, Decile KC, Berghaus LJ, et al. Concentrations of cysteinyl leukotrienes in urine and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of cats with experimentally induced asthma. Am J Vet Res. 2003;64(11):1449-53.

- Reinero CR, Decile KC, Byerly JR, et al. Effects of drug treatment on inflammation and hyperreactivity of airways and on immune variables in cats with experimentally induced asthma. Am J Vet Res. 2005;66(7):1121–7.

- Schooley EK, McGee Turner JB, Jiji RD, et al. Effects of cyproheptadine and cetirizine on eosinophilic airway inflammation in cats with experimentally induced asthma. Am J Vet Res. 2007;68(11):1265–71.

- Cohn LA, DeClue AE, Cohen RL, et al. Dose effects of fluticasone propionate in an experimental model of feline asthma. In: 2008 American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Forum Proceedings; June 4-7, 2008; San Antonio, TX.

- Mitchell RW, Cozzi P, Ndukwu M, et al. Differential effects of cyclosporine A after acute antigen challenge in sensitized cats in vivo and ex vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 1998; 123:1198–204.

- Leemans J, Kirschvink N, Cambier C, et al. Oral and inhaled corticosteroids decrease eosinophilic airway inflammation and bronchial reactivity in Ascaris sensitized and challenged cats. In: Proceedings of the 26th Annual Veterinary Comparative Respiratory Society Scientific Forum; October 29-November 1, 2008; Oklahoma City, OK.

- Scherk M. Bronchopulmonary disease in cats—is it really asthma? In: Proceedings of the 2010 Wild West Veterinary Conference; October 13-17, 2010; Reno, NV.

- Cameron ME, Casey RA, Bradshaw JWS, et al. A study of environmental and behavioural factors that may be associated with feline idiopathic cystitis. J Small Anim Pract. 2004;45(3):144–7.

- Kruger JM, Conway TS, Kaneene JB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of short-term amitriptyline administration for treatment of acute, nonobstructive, idiopathic lower urinary tract disease in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222(6):749-58.

- Dorsch R, Zellner F, Schulz B, et al. Evaluation of meloxicam for the treatment of obstructive feline idiopathic cystitis. J Feline Med Surg. 2015 Dec 15 [Epub ahead of print].

- Robertson SA, Lascelles BDX, Taylor PM, et al. PK‐PD modeling of buprenorphine in cats: intravenous and oral transmucosal administration. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2005;28(5):453-60.

- Lulich J, Osborne C. Prazosin in cats with urethral obstruction. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;243(9):1240.

Back to Top