Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Addressing Questions About Head Lice Management in the Community

BACKGROUND

One of the most common and least harmful infestations is caused by Pediculus humanus capitis, a parasite that is also known as the head louse. Head lice infestations create social stigmas and are a nuisance among school-age children, especially children from 3 to 11 years of age, throughout the United States (U.S.).1 Infestations are estimated to occur at a rate of 6 to 12 million cases per year in the U.S., although reliable data is hard to obtain, since reporting of infestations is not required by most health deparments.1 Head lice infestations are not a health hazard to the public and they affect every socioeconomic group, regardless of personal hygiene. An estimated $1 billion dollars is spent on treatment costs for head lice infestations each year.2 It is essential that pharmacists understand common misconceptions about head lice and educate parents and caregivers on how to approach the treatment of head lice, including the availability of prescription medications and the emerging resistance to over-the-counter products.

THE LIFECYCLE OF THE HEAD LOUSE

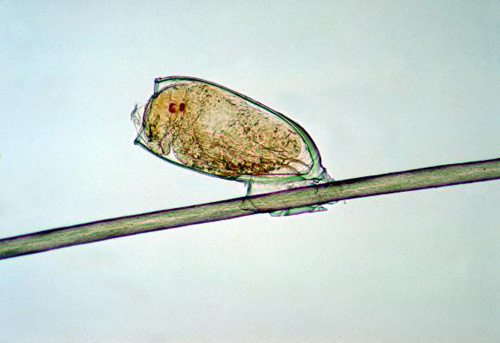

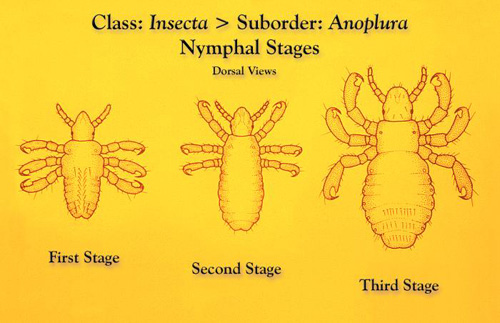

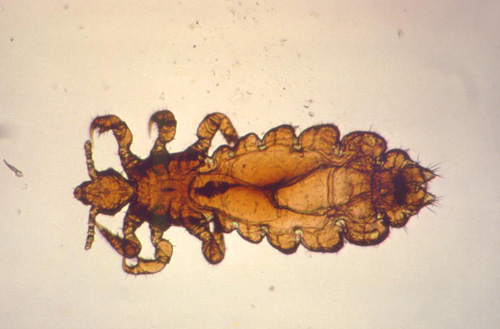

The louse starts as an egg that attaches to the hair shaft of the infested individual. The egg is usually found within 1 cm of the scalp because it relies on scalp temperature to stay warm. It hatches within 7 to 12 days, depending on body temperature (Figure 1).2,3 The empty egg casing may appear whitish or light yellow in color, but a viable egg is usually harder to see, since it matches the hair color by camouflaging itself with pigment. Both the egg and the empty egg casing have been referred to as "nits," depending on the source,2 and the lack of consistency in the definition of a nit can lead to confusion among patients. After hatching, the louse, referred to as a nymph, will take 9 to 12 days to develop into an adult louse, which appears tan in color and is approximately the size of a sesame seed. The development occurs through 3 nymph stages (Figure 2).4,6 The entire cycle takes roughly 3 weeks. An adult female louse can lay more eggs and the cycle can begin once again (Figure 3).5,6 An adult louse can survive for approximately 30 days while attached to an infested individual's hair and less than 1 day away from the scalp.6

Figure 1. Nymph of head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis)

that is about to emerge from an egg.

Figure 2. The 3 nymphal stages through which a typical louse passes on its way

to becoming an adult insect.

Figure 3. Adult Female Louse

DIAGNOSIS OF HEAD LICE INFESTATION

Lack of knowledge can lead to misdiagnosis of head lice. The diagnosis of an infestation should be made only after finding live head lice and not solely by identifying a patient with nits. Likewise, a diagnosis should not be made only if a patient has pruritus or is itching.2 In a study conducted by Pollack et al,7 the authors invited health care providers and other nonspecialized personnel (e.g., acquaintances, relatives, teachers, and barbers/beauticians) to submit specimens assumed to be representative of a louse or a nit. The study collected a total of 614 submissions from 541 subjects over an 18-month period. The authors concluded that less than 60% (364 specimens) of the specimens were lice or eggs. The remaining specimens contained various items including egg casings, dandruff, and other arthropods (e.g., book lice, mites). Of the 364 specimens, 53% (194 specimens) were viable eggs or lice. One interesting finding of the study included a discussion of how school personnel (e.g., nurses, teachers) and relatives were able to more accurately diagnose head lice infestations than physicians, although most were unable to distinguish an active infestation from an inactive infestation. Of note, the sample size of physicians was relatively small compared to school personnel and relatives: 42 compared to 203 and 204, respectively. This study does support the difficulty that exists with making accurate diagnoses and the likelihood for misdiagnosis or misidentification of head lice infestations, which can lead to inappropriate treatment.

MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT HEAD LICE

Many misconceptions regarding head lice exist and, as health care professionals, pharmacists should debunk myths and educate the public about the facts of head lice infestations. A few common myths about head lice are highlighted in Table 1.1,8-10 Some of the misconceptions relate to which groups of people are affected by head lice and how head lice are transmitted from person to person. Head lice are found in the U.S. and in other countries including Canada, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Australia.7 Head lice infestations affect all socioeconomic groups, with little regard to cleanliness or personal hygiene. Head lice are more prevalent in environments where children aged 3 to 11 years congregate, including day care centers, elementary schools, and summer camps. Head lice spread from one child to another most commonly by head-to-head contact. Head lice are less commonly spread by sharing of personal belongings (e.g., hats, brushes, hair ties, blankets, and clothing). A louse is only able to move by crawling and it cannot hop, jump, or fly. Once a louse is away from a person's scalp, it can live for less than 24 hours, since a louse feeds from the scalp every few hours and eggs require the warmth of the scalp to hatch. Lice cannot be spread by pets, including cats or dogs. Head lice are often confused with body lice, which have been shown to serve as vectors and spread bacterial infections, but head lice do not spread disease.11 Head lice infestations may be itchy to the scalp and cause a patient to scratch the scalp, possibly leading to a secondary skin infection. Misconceptions can lead to negative social stigmas and it is important for health care professionals to educate the public to ensure that families understand the facts regarding head lice infestations.

| Table 1. Common Head Lice Myths1,8-10 |

| Myth |

Truth |

| Head lice can hop, jump, or fly |

Head lice travel by crawling; they cannot hop, jump, or fly |

| Head lice are easily acquired from sharing brushes, hats, or clothing |

Head lice are most commonly spread by head-to-head contact; acquiring head lice from sharing personal belongings is uncommon |

| Head lice can live everywhere |

Head lice can survive less than 24 hours away from the body |

| Head lice only affect lower socioeconomic classes or people with poor hygiene |

All socioeconomic groups are affected by head lice, regardless of cleanliness or personal hygiene |

| Pets can carry and spread head lice |

Only humans can spread head lice; pets cannot spread head lice |

| Head lice spread disease |

A secondary skin infection can occur from excessive scratching of the skin, but head lice do not spread illness |

| Anyone with nits has an active head lice infestation |

Only someone with a live louse (nymph or adult) on the scalp or hair is diagnosed with having an active head lice infestation |

| Head lice are the same as nits |

Head lice are insects, while nits are the eggs laid by the adult female louse |

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR HEAD LICE INFESTATIONS

Treatment options for head lice infestations include both over-the-counter and prescription options (Table 2).12-17 Many of the treatment options for head lice are pediculicidal and neurotoxic pesticides that exert a mechanism of action resulting in hyperexcitability of the neurons, paralysis of the louse, and eventual louse death, since the louse is unable to feed while paralyzed.15 Benzyl alcohol is the exception: it is not a pesticide and is not neurotoxic; instead, it exerts a mechanism of death by asphyxiation.14 Only a few medications have ovicidal activity and exert any effect on lice eggs (Table 2).12-17 Eggs that are located within 1 cm of the scalp are still considered viable and, after treatment, efforts should be made to manually remove nits with nit combs or fine-tooth combs, since none of the treatment options are 100% effective for killing the eggs.2 Each treatment option has different instructions for use and it is imperative for pharmacists to take an active role in counseling on appropriate instructions for use.

| Table 2. Treatment Options for Head Lice Infestations According to Prescription Status, Approved Age for Use, and Ovicidal Activity 12-17 |

| Product (Brand) |

Prescription status |

FDA approved age for use |

Ovicidal activity |

| Permethrin 1% lotion or cream rinse (Nix) |

OTC |

≥ 2 months |

No |

| Pyrethrins 0.33% + piperonyl butoxide 4% shampoo (A-200, Licide, Pronto, RID) |

OTC |

≥ 2 years |

No |

| Benzyl alcohol 5% lotion (Ulesfia) |

Rx |

≥ 6 months |

No |

| Ivermectin 0.5% lotion (Sklice) |

Rx |

≥ 6 months |

Not directly |

| Malathion 0.5% lotion (Ovide) |

Rx |

≥ 6 years

Contraindicated in neonates and infants |

Yes |

| Spinosad 0.9% suspension (Natroba) |

Rx |

≥ 6 months |

Yes |

| Abbreviations: FDA = United States Food and Drug Administration; OTC = over the counter; Rx = prescription only. |

Over-the-counter treatment options

The first line treatment options for primary treatment of head lice infestations are the self-treatment topical medications available without a prescription: permethrin (1% lotion or cream rinse) and pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide (0.33%/4% shampoo). Permethrin is synthetically derived and pyrethrins are extracted from chrysanthemum plants. Pyrethrins should be avoided in any patient who is allergic to the chrysanthemum plant.1,13 Permethrin is approved for use in children as young as 2 months of age, but pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide is only approved for use in children 2 years of age and older. Both agents have similar mechanisms of action through inhibition and delayed repolarization of the voltage-gated sodium channel leading to hyperexcitability.12,13 Pyrethrins are formulated with piperonyl butoxide because piperonyl butoxide works synergistically to extend the action of pyrethrins.18 Neither permethrin or pyrethrins exert any ovicidal effect, necessitating a second treatment after 7 to 10 days, optimally at day 9, assuming all residual eggs have hatched within that time period.2 Administration varies for each of these agents: permethrin is applied to towel-dried hair and pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide is applied to dry hair. Both agents are indicated to remain on the hair for 10 minutes. The difference in application could confuse patients and, therefore, it is important for pharmacists to educate patients how to correctly apply each product. Overall, both over-the-counter (OTC) treatment options are well tolerated, with minor skin reactions (e.g., scalp discomfort, pruritus, burning) being the only notable adverse reactions.12,13

Prescription treatment options

Several prescription treatment options are available for treating lice infestations. The products differ in their mechanisms of action, administrations and directions for use, and levels of effectiveness. If resistance to permethrin or pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide has been identified in the community or if a patient fails therapy with an OTC treatment regimen, a prescription treatment option would be appropriate.2 The first line prescription treatment options include benzyl alcohol 5% lotion or malathion 0.5% lotion. Two newer options available with a prescription include ivermectin 0.5% lotion and spinosad 0.9% suspension, both of which should be reserved as second line agents for difficult to treat cases of head lice infestations. Patient age should be evaluated when choosing the most appropriate treatment option.

Benzyl alcohol 5% lotion. Benzyl alcohol 5% lotion is the only therapy available for head lice that is not neurotoxic to the louse. It works with other vehicles in the formulation to exert its effect on the respiratory system by obstructing respiratory spiracles.14 It has no effect on lice eggs and, similar to the over-the-counter products, requires a second treatment after 7 to 10 days. Benzyl alcohol is applied to dry hair to completely saturate the hair and the scalp. The appropriate amount of lotion per application is based on hair length (i.e., short, medium, or long) and is outlined in detail in the package insert.14 The application should remain on the hair for 10 minutes before being rinsed thoroughly. In a set of phase III trials conducted by Meinking et al,19 benzyl alcohol showed treatment successes of 92.2% and 75% on days 8 (1 day after second treatment) and 22, respectively. The authors concluded that the decline in treatment success was due to reinfestation and not treatment failure. Benzyl alcohol is associated with a low incidence of minor scalp irritation and mild eye irritation, but it is well tolerated overall.19 It is safe in children as young as 6 months of age; it should not be administered to neonates, since benzyl alcohol has been associated with gasping syndrome in neonates.14

Ivermectin 0.5% lotion. Ivermectin 0.5% lotion is an anti-parasitic agent that exerts a neurotoxic effect on head lice by changing the permeability of chloride ion channels in muscle cells. Ivermectin binds to the channels and creates a hyperpolarization of the cell.15 Ivermectin is not ovicidal; however, it is absorbed by the viable egg and the newly hatched nymph typically will not survive due to muscle paralysis and an inability to feed.20 In multiple studies, topical ivermectin 0.5% lotion was able to achieve a lice-free state in 73% of patients on day 15 after 1 treatment.20 Topical ivermectin is well tolerated in children 6 months of age and older: the most commonly reported adverse effect is pruritus, and, less commonly, a skin-burning sensation and eye irritation can occur. Ivermectin is available in a single-dose tube and patients should apply a sufficient amount (up to 1 tube) to completely cover the patient's dry hair and scalp.15 The lotion should be left on for 10 minutes. Ivermectin 0.5% lotion was the most recently approved product for head lice by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), receiving approval in 2012.15

Malathion 0.5% lotion. Malathion is an organophosphate, which exerts its effect by inhibiting cholinesterase activity.16 Its history includes removal from the U.S. market twice due to concerns over flammability, odor, and the prolonged application time.2 Malathion is the only lotion that is applied to and left on dry hair for 8 to 12 hours. The current formulation approved for use in the U.S. is formulated with other ingredients that have their own pediculicidal properties including dipentene and terpineol.2,18 Malathion also has ovicidal activity, though a second application may be needed if eggs hatch and live lice are present after 7 to 9 days.2,16 Adverse reactions to malathion are similar to other treatment regimens and include skin irritation, but it does have a risk of causing chemical skin burns and is highly flammable due to the high alcohol content.16 It is only approved for use in patients 6 years of age and older and its use is contraindicated in neonates and infants.

Spinosad 0.9% suspension. Spinosad is derived from an actinomycete bacterium in soil. The mechanism of action is hypothesized to include the inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and γ-aminobutyric acid-gated chloride channels leading to neuronal excitation.17 Clinical studies have supported treatment success for spinosad with efficacy rates of greater than 80%.21 Spinosad is applied to a dry scalp and rubbed gently until the scalp is thoroughly moistened. It is then applied to dry hair, which allows the scalp and hair to be completely covered. It remains on the scalp and hair for 10 minutes before being rinsed completely off. A second application is recommended if live lice are present after 7 days.17 Overall, spinosad is well tolerated in patients 6 months of age and older, with only minor adverse effects noted, including erythema of the scalp. Spinosad was initially approved by the FDA in 2011 for patients 4 years of age and older, but approval was extended in December 2014 to include patients as young as 6 months of age.17

TREATMENT FAILURES AND RESISTANCE

Persistent cases of head lice contribute to increasing resistance rates to over-the-counter products and to patients experiencing treatment failures. Some patients may be misdiagnosed either by not having live lice or by misidentification of another condition or infestation, such as dandruff, bed bugs, or other insects, as lice. Patients with adherence issues may experience reinfestation if the lice treatment is indicated to be reapplied and the application is not repeated as directed in 7 to 10 days. As described, the various head lice treatment options have different directions for use and patients who do not follow directions as instructed may inadvertently affect efficacy (Table 3).12-17 For these reasons, patients need education from a pharmacist or other health care professional to ensure optimal treatment and outcomes for head lice infestations.

| Table 3. Directions for Use of Head Lice Treatments12-17 |

| Product (Brand) |

Directions for application |

Duration to leave on hair |

Nit combing |

| Permethrin 1% lotion or cream rinse (Acticin, Elimite, Nix Creme Rinse) |

Apply immediately after hair is shampooed (without conditioner), rinsed, and towel-dried. Apply enough product to saturate hair and scalp (especially behind ears and on nape of neck). |

Leave on for 10 minutes. Rinse with warm water. |

Use fine-tooth comb to remove remaining nits. |

| Pyrethrins 0.33% + piperonyl butoxide 4% shampoo (A-200, Licide, Pronto, RID) |

Apply to dry hair and other infested areas (first applying to behind ears and back of neck). Apply enough solution to completely wet area. |

Leave on for 10 minutes. Use warm water to form a lather, shampoo, and then rinse thoroughly. |

Use fine-tooth comb to remove lice and eggs. |

| Benzyl alcohol 5% lotion (Ulesfia) |

Apply appropriate volume as indicated for hair length to dry hair and completely saturate the scalp. |

Leave on for 10 minutes. Rinse thoroughly with water. |

May use fine-tooth comb to remove nits and dead lice. |

| Ivermectin 0.5% lotion (Sklice) |

Apply sufficient amount (up to 1 tube) to completely cover dry scalp and hair. (For single-dose use only.) |

Leave on for 10 minutes (start timing treatment after scalp and hair have been completely covered). Rinse thoroughly with warm water. |

Nit combing is not required; may use fine-tooth comb to remove treated lice and nits. |

| Malathion 0.5% lotion (Ovide) |

Apply sufficient amount to cover and thoroughly moisten dry hair and scalp. |

Allow hair to dry naturally and shampoo after 8 to 12 hours. |

Use fine-tooth comb to remove dead lice and nits. |

| Spinosad 0.9% suspension (Natroba) |

Apply to dry scalp and rub gently until the scalp is thoroughly moistened, then apply to dry hair; completely cover scalp and hair. |

Leave on for 10 minutes (start timing treatment after scalp and hair have been completely covered). Rinse thoroughly with warm water. Shampoo may be used immediately after product is completely rinsed off. |

Nit combing is not required; may use fine-tooth comb to remove treated lice and nits. |

Resistance to commonly used pediculicides can develop over time. The risks of natural selection and lice mutation need to be clarified with future studies, but resistance to over-the-counter pyrethrins and permethrin has been associated with a target-site insensitivity due to a mutation within a subunit gene known as kdr or knockdown resistance.22 Currently, 3 mutations of this gene are reported in the literature, with the TI mutation demonstrating complete target-site insensitivity.23 A study was conducted by Yoon et al,23 to evaluate the frequency of the TI mutation in 18 locations among 12 U.S. states by collecting head lice from volunteers from 1999 to 2008. The results of the study showed that the mutation occurred with a frequency of 84.4%. It is important to note the small number of locations included in the study and that specimens were collected from urban and metropolitan collection sites; both of these factors could contribute to bias in the results. A study published in 2016 by Gellatly et al24 yielded similar results but with more collection sites among a larger number of U.S. states. Gellatly et al collected samples from 2013 to 2015 from 138 locations among 48 U.S. states, excluding Alaska and West Virginia. The results of the study showed that 42 of the 48 states reported a resistance allele frequency of 100%, which indicates fully resistant lice. The remaining 6 states showed mixed results. Both studies reveal that head lice resistance to the popular over-the-counter products is increasing and is now present throughout the U.S.

Resistance to prescription head lice treatments is reported less frequently than resistance to over-the-counter products. The U.S. formulation of malathion, which, as stated previously, contains other ingredients with their own pediculicidal properties, has low levels of reported resistance. Australia and European countries, including France, the United Kingdom, and Denmark, have higher documented rates of resistance to malathion than the U.S.25 Resistance outside the U.S. could be attributed to variations in the formulations of products (i.e., without additives) or to the continuous use of malathion.25 Current research has not identified a definitive mechanism of head lice resistance towards malathion, although, in other insects, a hypothesis has been proposed that includes metabolism by various esterases. Other agents, including benzyl alcohol, spinosad, and ivermectin, were approved after 2009 and, to date, resistance has not been reported.23

ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT OPTIONS

Oral ivermectin is not FDA approved for head lice, it could be an option in the situation of resistance. In a cluster-randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled trial conducted by Chosidow et al,26 oral ivermectin was compared to malathion lotion in patients who experienced treatment failure. The study evaluated a total of 812 participants who were at least 2 years of age. Patients were randomly assigned to receive treatment with oral ivermectin (dose of 400 µg/kg) or topical malathion on days 1 and 8. Efficacy was evaluated on day 15 and defined as participants being free of head lice. Overall efficacies were 95.2% in the intention-to-treat population and 85% for the patients receiving ivermectin and malathion. The overall efficacies were 97.1% in the per-protocol population and 89.8% for the patients receiving ivermectin and malathion. No statistically significant differences in side effects were observed between the groups in the study. Ivermectin should be avoided in patients weighing less than 15 kg and in those under 2 years of age due to a risk of increased central nervous system adverse effects.12 Oral ivermectin appears to be safe and effective, but further studies are needed to clarify its conditions and indications for use. Until safety and efficacy are established, physicians should select topical alternatives with clear safety profiles.

Lindane 1% shampoo is FDA approved for the treatment of head lice, but its use is not recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).1,2 Lindane has been associated with severe neurological toxicities, including seizures and death. Resistance has also been noted worldwide, further decreasing its favor for treating head lice infestations.19

Several home remedies have been proposed for treating head lice infestations: mayonnaise, petroleum jelly, margarine, and olive oil have all been used as occlusive agents. Some anecdotal information has indicated that petroleum jelly shows better mortality than other home remedies and decreases the lice survival rate to 38%.6 To date, conclusive information for home remedies does not exist to support efficacy and use, and home remedies are not recommended by the AAP.2

"NO NIT" POLICIES

In 2002, the AAP and the National Association of School Nurses (NASN) discouraged schools from having "no nit" policies. Instead, the AAP recommended that students with a head lice infestation be allowed to return to school after receiving proper treatment for head lice.27 A "no nit" school district-wide policy forces absenteeism for students with head lice and/or nits despite treatment and only allows students to return to school when they are free of nits and lice, as determined by the school nurse. This type of policy adds to the economic burden of head lice treatment, including costs related to lost parental wages and/or cost of child care if parents are unable to stay home with children.28 The policy also impacts student loss of education. A study by Price et al,29 published just 3 years before the AAP and NASN statement against "no nit" policies highlighted the perceptions of school nurses towards head lice. The survey was conducted of 382 school nurses. Results showed that most nurses (96%) sent a child home from school until the head lice were treated. Only 25% allowed a child back into school if nits were remaining. At that time, 60% of school nurses supported a "no nit" policy and forced absenteeism. Only 7% referred children to a physician for additional treatment. Further, 75% of nurses agreed it was critical to have a child be completely nit free in order to prevent transmission of head lice to other children. The survey highlights the difficulties in changing perceptions regarding head lice transmission and treatment.

In 2015, the AAP published an updated clinical report on head lice and added stronger language stating that head lice should not restrict a child from attending school. The AAP urges schools to abandon such policies that force absenteeism and prevent students from attending schools, going so far as to suggest these policies may violate a child's civil liberties.2 The NASN updated its Position Statement on Head Lice Management in the School Setting in 2016.30 The NASN discourages the disruption of a child's educational process and recommends allowing a student to continue with the school day by remaining in class and participating in scheduled activities. The position statement further recommends parents and caregivers be notified of the situation at the end of the school day to minimize disruption to the parents' or caregivers' work. Previously, schools were encouraged to have mass screenings of students for head lice and nits; however, the NASN discourages those measures, since they are not cost-effective and have not been shown to be beneficial. Ultimately, the NASN recommends that schools abandon the policy of restricting attendance to school for children with head lice or nits and, instead, allow students to continue their educations.

PATIENT EDUCATION

When counseling patients about head lice, it is important to debunk common misconceptions that patients and family members have. Only patients with confirmed diagnoses of live head lice should receive treatment. Treatment should be applied exactly as indicated on the directions for the individual product and care should be taken to always protect the patient's eyes with a towel during application. Nit combing with a fine-tooth comb or "nit comb" is recommended after the hair has been treated with permethrin or pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide; nit combing is also encouraged after using benzyl alcohol or malathion to remove dead lice and nits. Nit combing is not required for topical ivermectin or spinosad. If 1 member of a household has an active infestation, other members and close contacts should be examined for live lice, but they should only receive treatment if a diagnosis of an infestation is confirmed.9,10 Items with which patients with an active infestation were in contact, including clothing, bedding, linens, and hats, should be laundered in hot water within 3 days of the patient receiving treatment. Items unable to be laundered should be placed in a sealable plastic bag for at least 2 weeks. Hair supplies, including brushes and combs, should be disinfected by soaking in hot water for 5 to 10 minutes.

Pharmacists should be able to obtain reputable resources regarding head lice and should supply patients with accurate information. The following organizations provide reliable, current information that is easily available and accessible to most patients, caregivers, and health care professionals:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov)

- National Association of School Nurses (www.nasn.org)

- American Academy of Dermatology (www.aad.org)

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (www.fda.gov)

- Healthy Children (by the American Academy of Pediatrics) (www.healthychildren.org)

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites - Lice - Head Lice: Epidemiology & Risk Factors. www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/epi.html. Updated September 24, 2013. Accessed January 15, 2017.

- Devore C, Schutze G. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1355-e1365.

- Image 379: Nymph of head louse, Pediculus humanus var capitis parasite, that was about to emerge from egg. 1979. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Image Library. https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/details_linked.asp?pid=379. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- Image 6818: This illustration depicts the three nymphal stages through which a typical louse passes on its way to becoming an adult insect. 1975. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Image Library. https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/details_linked.asp?pid=6818. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- Image 19067: This photomicrograph depicts a dorsal view of an adult female human head louse, Pediculus humanus var. capitis. 1979. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Image Library. https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/details_linked.asp?pid=19067. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- Wadowski L, Balasuriya L, Price HN, O'Haver J. Lice update: new solutions to an old problem. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33(3):347-354.

- Pollack RJ, Kiszewski AE, Spielman A. Overdiagnosis and consequent mismanagement of head louse infestations in North America. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(8):689-693.

- The Truth About Head Lice. Sanofi Pasteur and the National Association of School Nurses. http://www.nasn.org/portals/0/resources/headlice_myths_facts.pdf. Accessed on January 15, 2017.

- Head Lice: What Parents Need to Know. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/from-insects-animals/Pages/Signs-of-Lice.aspx. Updated May 5, 2015. Accessed on January 15, 2017.

- Treating Head Lice. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm171730.htm. Updated January 2, 2017. Accessed on January 15, 2017.

- Sangaré A, Doumbo O, Raoult D. Management and treatment of human lice. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:8962685.

- Nix [product information]. Trevose, PA: Insight Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2013.

- RID [product information]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare, LLC; 2015.

- Ulesfia [package insert]. Atlanta, GA: Sciele Pharma, Inc; 2010.

- Sklice [package insert]. Swiftwater, PA: Sanofi Pasteur Inc; 2012.

- Ovide [package insert]. Hawthorne, NY: TaroPharma; 2005.

- Natroba [package insert]. Carmel, Ind: ParaPRO LLC; 2014.

- Lebwohl M, Clark L, Levitt J. Therapy for head lice based on life cycle, resistance, and safety considerations. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):965-974.

- Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M, et al. The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (Ulesfia): a safe and effective topical treatment for head lice (pediculosis humanus capitis). Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(1):19-24.

- Deeks LS, Naunton M, Currie MJ, Bowden FJ. Topical ivermectin 0.5% lotion for treatment of head lice. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(9):1161-1167.

- Villegas S, Breitzka R. Head lice and the use of spinosad. Clin Ther. 2012;34(1):14-23.

- Bouvresse S, Berdjane Z, Durand R, et al. Permethrin and malathion resistance in head lice: results of ex vivo and molecular assays. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(6):1143-1150.

- Yoon KS, Previte DJ, Hodgdon HE, et al. Knockdown resistance allele frequencies in North American head louse (Anoplura: Pediculidae) populations. J Med Entomol. 2014;51(2):450-457.

- Gellatly KJ, Krim S, Palenchar DJ, et al. Expansion of the knockdown resistance frequency map for human head lice (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) in the United States using quantitative sequencing. J Med Entomol. 2016;53(3):653-659.

- Durand R, Bouvresse S, Berdjane Z, et al. Insecticide resistance in head lice: clinical, parasitological and genetic aspects. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(4):338-344.

- Chosidow O, Giraudeau B, Cottrell J, et al. Oral ivermectin versus malathion lotion for difficult-to-treat head lice. New Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):896-905.

- Frankowski BL, Weiner LB; Committee on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):638-643.

- Hansen RC, O'Haver J. Economic considerations associated with Pediculus humanus capitis infestation. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2004;43(6):523-527.

- Price JH, Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Islam R. School nurses' perceptions of and experiences with head lice. J Sch Health. 1999;69(4):153-158.

- Head Lice Management in the School Setting: Position Statement. National Association of School Nurses. www.nasn.org/PolicyAdvocacy/PositionPapersandReports/NASNPositionStatementsFullView/tabid/462/ArticleId/934/Head-Lice-Management-in-the-School-Setting-Revised-2016. Revised January 2016. Accessed January 15, 2017

Back to Top