Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Improving Preventive Oral Care to Enhance Overall Health: The Pharmacist's Role

INTRODUCTION

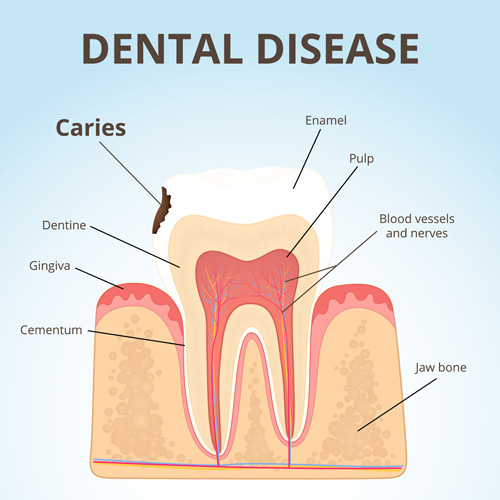

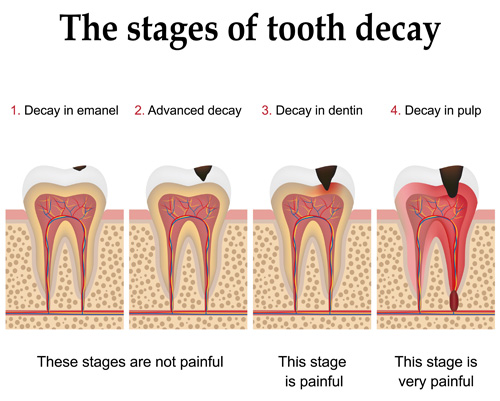

A growing body of evidence shows that patients' oral health is inextricably linked to their systemic health – what is good for one is often good for the other. Dental caries (see Figures 1 and 2) are perhaps the most common infectious affliction of people worldwide.1 Untreated periodontal disease creates a palm-sized open wound — something no pharmacist or other health professional would ignore if it were anywhere but the mouth. The historical mouth/body divide is now recognized as problematic, and movements are under way to "put the mouth back in the body" by making oral health the purview of all health professionals2 and to bring a dental benefit to Medicare coverage.3

Figure 1. Tooth structure and development of caries.

|

Figure 2. Stages of tooth decay

|

A key component of oral health is prevention of caries (dental decay, or cavities), gingivitis (gum inflammation), periodontitis (inflammation of the gums, which can lead to gum recession and associated problems), and other diseases of the mouth (dry mouth, mouth sores, oral cancer). Most community and ambulatory pharmacies have an extensive inventory of oral health supplies, placing the pharmacist in a position to influence and reinforce patients' daily oral preventive care. Combined with regular check-ups by dental professionals, daily oral hygiene forms the basis for prevention of problems and maintenance of a healthy mouth.

This continuing education article provides pharmacists with an overview of the connection between oral and systemic health, common oral health problems, special considerations for older patients and smokers, medicines that affect the mouth and associated structures, oral health products, and oral health needs of patients.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN ORAL AND SYSTEMIC HEALTH

The mouth has numerous important functions in people's lives, from intake and initial digestion of foods to speech communications and provision of nonverbal and social cues. Without a healthy mouth, diets can be compromised, nutrition can suffer, and people can withdraw from social interactions because of their physical appearance or inability to eat normal foods. The result can be social isolation and depressed affect as diseases of the mouth take their toll on the psyche and general outlook on life.

Beyond these general benefits, the healthy mouth has additional bidirectional and previously underrecognized interactions with other diseases and organ systems of the body. In a landmark report issued in 2000, the U.S. Surgeon General referred to the mouth as a mirror of health and disease occurring in the rest of the body. By paying attention to the condition of the mouth, clinicians can get valuable insights about general health problems such as nutritional deficiencies, systemic diseases (including diabetes and cardiovascular and respiratory disease), microbial infections, immune disorders, injuries, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and some cancers.4

Despite an increasing body of literature examining the link between systemic and oral diseases, lack of funding as well as ethical limitations prevent researchers from conducting randomized controlled trials needed to prove causation. Most studies are observational in design and are thus unable to show that one disease causes another. While some datasets are quite large – such as insurance claims for millions of covered lives — the evidence supports associative rather than causative relationships.

Some associations are bidirectional; as with the chicken and the egg, it is difficult to know which came first. For instance, patients with poorly controlled diabetes have a 3-fold increase in risk of developing gingivitis and periodontal disease, and tooth loss is more common in those with diabetes than in matched controls. Patients with diabetes have better metabolic control when their periodontal disease is treated.5–7

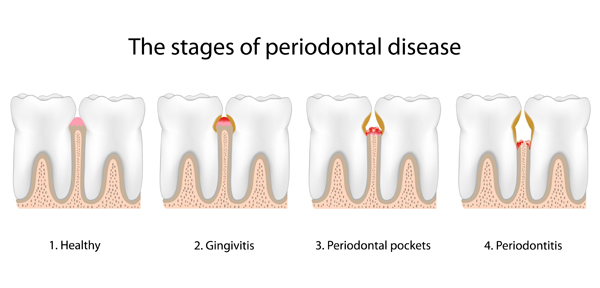

One of the mechanisms thought to be involved in the diabetes–oral health relationship is decreased immunity associated with elevated glucose levels. In the mouth of a person with decreased immunity, bacteria can more easily form biofilms (plaque and calculus/tartar) that can cause gingivitis, leading to gum recession, periodontal disease, and ultimately loss of teeth (see Figure 3). Diabetic neuropathy can also decrease salivary gland function, causing dry mouth and increasing patients' risk of oral disease.8,9

Figure 3. Stages of periodontal disease.

|

Periodontal disease can likewise lead to poorer diabetes outcomes. Presence of pathogenic bacteria in the mouth with diseased gums leads to septicemia, increasing inflammatory processes throughout the body and worsening glycemic control. Prediabetes or diabetes can develop. To stymie this cascade, meticulous oral care is needed, along with proper management of glucose levels.

The impact of better management of periodontal disease on diabetes outcomes and costs has been demonstrated through analysis of large insurance databases. In a report from the health care consulting firm Avalere, annual reductions in medical costs were estimated at $1,300 to $3,200 per person when patients with diabetes had periodontal treatments. Based on these and other savings, the firm estimated $12 in averted costs for every $1 spent on periodontal care in medically complex patients, including those with congestive heart failure or chronic kidney disease.10

Respiratory disease is another condition in which a link with oral health is firmly established. Microbial pathogens present in the mouth of a person with periodontitis can be transported easily into the respiratory passages through air and secretions. Respiratory conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder are associated with lung infections, release of inflammatory factors, and other pathophysiologic changes that can worsen oral disease.11–13

Cardiovascular diseases have also been linked to oral health through observational data and insurance claims. As with diabetes, inflammatory factors are common mediators involved in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases such as stroke and myocardial infarction, and these are worsened by periodontal disease. In an analysis of insurance claims data, significant improvements in outcomes and costs were identified when patients with cardiovascular disease or coronary artery disease were treated for periodontal disease.14,15

COMMON ORAL HEALTH PROBLEMS

Oral diseases represent a major public health burden throughout the world. Caries, periodontal disease, oral cancer, and cleft lip and palate affected 3.9 billion people in 2010, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease.1 As analyzed by Jin et al.,16 these oral diseases accounted for 18.8 million disability-adjusted life–years. Compared with figures from 1990, the burden for periodontal disease, caries, and oral cancer increased by 46% during this time period. The increase paralleled the climb in prevalence of major noncommunicable disease such as diabetes, which went up by 69% during this time period, adding to the evidence of an association between these conditions.

People are at risk for dental caries throughout the lifespan. Dental caries are transmissible bacterial infections on the surfaces of teeth caused by proliferation of species such as Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, or lactobacilli when fermentable carbohydrates are available; organic acids are produced as waste products. The acids demineralize the tooth surface; if the process is not stopped or reversed, carious lesions form at these sites.17

Caries can develop on the crowns of teeth (dental or coronal caries) or on root surfaces (root caries) in the presence of gum recession. Dental caries are incorrectly associated in some people's minds as occurring primarily in younger people, but they can occur at any time throughout an individual's life. Because older adults are keeping their natural teeth longer, caries rates have increased in older adults.

Root caries occur primarily in older adults. Prevention using fluoride and/or other interventions is important, as treatment of root caries is difficult. The decay can extend below the gum line, and tooth breakage is common, leading to the need for tooth extraction. Ethical concerns are also a factor, as practitioners would generally not perform restorative procedures when patients do not have access to follow-up care or the capacity for oral hygiene needed for maintenance and future prevention.17 Pharmacists can help with prevention of root caries by making sure that exposure to sugars in drug products is minimized, medications that dry the mouth are discontinued or replaced whenever possible, and patients understand which supplies are needed for daily oral hygiene (including products for tooth and gum sensitivity and/or fluoride-containing toothpastes and when necessary, mouth rinses).

Periodontal disease develops when poor oral hygiene, diminished immunity, or other factors allow the biofilm to invade the tissues surrounding the teeth, producing inflammation (see Figure 3). Left untreated in susceptible people, the resulting gingivitis can progress to periodontitis (inflammation of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone that supports the teeth). Periodontal disease can develop at any age; it is especially common in older adults as a result of disease progression and of more people keeping their natural teeth longer.18

Loss of any teeth (other than the commonly removed third molars) can be problematic for oral health. Adjacent or opposing teeth can become more unstable, leading to further tooth breakage, mobility, and extractions. Data from the 2011–12 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that about one-half of American adults (48%) aged 20–64 years of age had a full set of natural teeth (excluding third molars). Age- and race-related disparities were evident; two-thirds of those aged 20–39 years had all their teeth, compared with one-third of those 40 to 64 years of age. Non-Hispanic blacks were least likely to have all their teeth (38%), compared with 45% with Hispanics, 49% of Asians, and 51% of whites.19

Edentulism is the loss of all natural teeth. By the age of 60 years, about 25% of Americans no longer have any natural teeth.20 This limits mastication, consumption of a normal nutritious diet, speech, and social interactions, leading to a lower oral health–related quality of life.21 Edentulism in older adults has also been associated with loss of functional capabilities (activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living), increased morbidity as health declines and frailty ensues, and increased mortality.22,23

Xerostomia, or dry mouth, is associated with increased rates of oral disease. While a common complaint among older patients, xerostomia — defined as the perception of oral dryness — is not a normal part of the aging process. Rather, the condition can result from use of anticholinergic medications or those alter fluid balance (e.g., diuretics), or it can be a true decrease in salivary gland output as a result of disease or therapies such as radiation for head or neck cancer. Symptoms associated with xerostomia include a sensation of a dry, sticky mouth and tongue, thick saliva, mouth soreness, altered taste, increased thirst, and difficulty speaking, eating, and swallowing.24

Adequate salivation is an important factor in good oral health. Saliva helps keep oral microbes in check, keeping teeth and gums healthy. It is involved in digestion of carbohydrates in the mouth and preparation of foods for swallowing. Decreased salivation rates, including those seen in patients with Sjögren's syndrome or treated with high doses of radiation for oral or head cancer, are associated with increased rates of caries and periodontal disease.24

Edentulous patients who are fitted with prostheses (full or partial dentures, implants) face continued challenges to their oral health. Stomatitis (inflammation of mucosal tissues of the mouth) is common in patients with poor oral health. The term denture stomatitis refers specifically to lesions caused by fungal infections in those with prostheses. Because of the risk of lesions progressing to inflammatory papillary hyperplasia, causes of denture stomatitis should be addressed. These include poorly fitting dentures and inadequate cleaning of dentures using the products and procedures detailed in the below section on Oral Health Products. Some studies have shown that lesions can be treated simply by improving the cleaning of dentures, thereby avoiding use of topical antifungal agents in the mouth; cleaning can also be an addition to antifungal treatments.25,26

ORAL HEALTH PROMOTION IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS

As key members of the health care team, pharmacists have an important role to play in addressing the oral health issues of their patients.11,27 As health care moves toward eliminating the medical/dental and mouth/body divisions in care,2 pharmacists will be called on to be knowledgeable about oral health issues and advise patients about daily oral hygiene and management of oral health issues. Some oral health advocates are also calling for state regulatory boards to expand scope of practice laws for many types of health professionals, including pharmacists, to be able to examine the mouth and perform some procedures such as application of fluoride varnishes when indicated.28

Of the health professionals, pharmacists are very accessible, providing a consultative role that is especially important for disadvantaged patients who lack access to dentists and other oral health professionals.11,29 Pharmacists currently are consulted for many health-related issues, including dispensing prescription medications, providing advice concerning OTC medications, responding to patients presenting with signs and symptoms of oral conditions, referrals to oral health professionals, smoking cessation, reinforcement of the relationship between chronic systemic diseases and oral hygiene, advice on oral products, and monitoring medications for adverse effects such as xerostomia or osteonecrosis.11

In a recent survey of 345 pharmacies in the United Kingdom, 99.4% of respondents recognized that there was a role for pharmacists in oral health promotion. These pharmacists reported a fairly high level of knowledge for most of the common oral conditions, but also indicated an interest in further training.29 Pharmacists who receive oral health–related training will be able to provide more appropriate counseling on the causes of dental problems and methods of prevention and treatment.11

Pharmacists can target two special populations in particular as they look for ways to expand their oral health services and expertise. Older patients are often taking several prescription and OTC medications for numerous chronic diseases. As discussed in the next section, pharmacists should monitor these patients' pharmacotherapy closely for medications associated with adverse oral health events, and talk with both patients and any involved caregivers about the importance of daily oral care. In those with conditions such as arthritis that could impede their ability to properly brush and floss the teeth, pharmacists can provide information the advantages of powered toothbrushes and floss threaders (discussed below). Caregivers for patients with dementia appreciate the pharmacists' reinforcement of ways they can help their loved ones with the daily oral care that can prevent decline into oral disease, worsening of systemic disease, and ultimately impairment of activities of daily living and development of frailty.

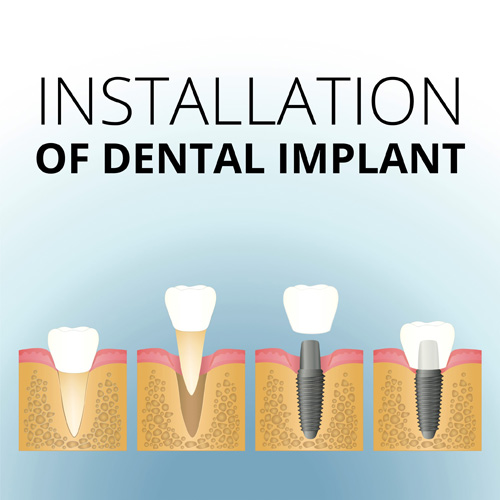

Smokers and other tobacco users also need to hear from pharmacists about the oral health advantages of cessation and the treatments that can help them stop using these products. Dental disease and oral cancers are associated with use of tobacco products; periodontal disease and peri-implantitis (inflammation around a dental implant) can result. In addition to smoking and smokeless tobacco, waterpipe tobacco smoking and use of electronic cigarettes are associated with these increased risks.30

Pharmacists should leverage the oral risks in moving tobacco users along the cessation motivation pathway. Pharmacists should also be aware of the signs and symptoms of oral cancer (oral burning sensations; white, red, or speckled patches; ulcers that do not heal) and refer patients with these conditions for medical care rather than recommending OTC products.31,32 As the interprofessional oral health movement advances, pharmacists may also find dentists and other oral health professionals interested in partnering in helping tobacco users with cessation therapies.33

ORAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS OF PRESCRIPTION AND OTC MEDICATIONS

Oral health is an important therapeutic area for pharmacists. Not only are OTC and prescription medications commonly used for pain of the mouth and gums, adverse effects in the oral cavity must be considered when a number of drugs are used for other indications. A complete review of medications with beneficial or detrimental actions on the oral cavity is beyond the scope of this article; some of the more common considerations are mentioned here.

Dental pain and oral lesions are among the most common reasons people seek OTC products in pharmacies. Products include analgesics for pain, teething powders and tablets (some of which are homeopathic and controversial) in infants and young children, and agents for canker sores and other oral lesions, ulcerations, stomatitis, and thrush or candidiasis. Young children (age <8 years) should avoid use of tetracyclines (including doxycycline and tigecycline) because of tooth discoloration; an exception can be made when benefits outweigh this concern, as in patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

As mentioned above, medications that dry the mouth can decrease patients' natural defenses against the bacteria that cause dental caries. When these drugs are used in older adults with gum recession and periodontal disease, root caries can develop, leading to tooth breakage and the need for extensive restoration or extractions. The Beers list of medications to avoid in older adults is a good guide to consult for identifying the most problematic of the many anticholinergic drugs that should be avoided in older adults; first-generation antihistamines are specifically called out for their propensity to cause dry mouth, and other strongly anticholinergic agents are on the list in other contexts.34

Osteonecrosis is another medication adverse effect that has proven difficult to manage in the decade since the association was first recognized. Bisphosphonates and denosumab use has been linked to increased risk of osteonecrosis, especially in patients undergoing dental procedures. These agents are used for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis but also in those with metastatic bone cancer.35,36

ORAL HEALTH PRODUCTS

For those with perfect teeth and those with advanced periodontal disease, the same two preventive interventions are critical: daily oral hygiene and regular professional examinations and cleanings. In some ways, daily care is more important than professional attention. Proper home care can avoid the need for many professional interventions, but poor daily hygiene can squander thousands of dollars spent for restorative care and ultimately lead to one extraction after another, despite dental professionals' best efforts.

Approximately two-thirds of pharmacists practice in community settings where toothpastes and other oral care products are frequently purchased. Pharmacists can inform patients of their recommendations on the oral health aisle (see Tables 1 and 2 for considerations in product selection), helping parents choose products for children, advising the more than one-half of American adults with gingival recession, and helping caregivers with the special care needed by older adults and those lacking the manual dexterity needed for oral care.29,37

| Table 1. Considerations when choosing among oral health products |

| Products |

Factors to consider during selection |

| Toothbrushes |

Manual versus powered |

For powered models, replaceable batteries versus rechargeable |

Bristle type and stiffness |

Shapes and sizes of handles, brush heads, bristle arrangements |

| Dentifrices |

Pastes, gels, powders |

Type of abrasives |

Fluoride sources |

Type of detergents |

| Interdental plaque removal devices |

Flosses |

Floss threaders |

Brushes |

Picks |

| Mouth rinses |

Fluoride content |

Antimicrobial activity |

Alcohol content |

Moisturizers and lubricants |

| Denture care |

Brushing |

Soaking |

Food "pocketing" |

Adhesives, maintenance procedures |

| Table 2. Common active/key ingredients in toothpastes and mouth rinses |

| Ingredients |

Advantages/disadvantages |

Key products with ingredient |

| Caries control |

|

|

| Sodium fluoride |

Better-tasting and less expensive than stannous fluoride; lacks bactericidal properties |

Colgate for Kids Toothpaste (Colgate-Palmolive Co.); Sensodyne Toothpaste (GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare); ACT Anticavity Fluoride Rinse (Chattem) |

| Sodium monofluorophosphate |

Similar in efficacy and properties to sodium fluoride |

Aquafresh for Kids Toothpaste (GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare); Tom's of Maine Natural Anticavity Fluoride Toothpaste (Tom's of Maine) |

| Stannous fluoride |

Kills bacteria; antisensitivity, antiplaque, antigingivitis properties; contains tin, which has been associated with tooth stains |

Crest Pro-Health Toothpaste (Procter & Gamble) |

| Plaque/gingivitis control |

|

|

| Triclosan |

Used for preventing gingivitis |

Colgate Total Advanced Deep Clean Toothpaste and Colgate Total Whitening Gel (Colgate-Palmolive Co.) |

| Sodium fluoride |

In addition to fluoride source, is useful for controlling plaque and gingivitis |

Crest Pro-Health Extra-Whitening Power Toothpaste (Procter & Gamble) |

| Eucalyptol, menthol, methyl salicylate, thymol |

Combination approach for plaque and gingivitis control; used with high amounts of alcohol (>20%) |

Listerine Antiseptic (Johnson & Johnson Consumer; numerous store brands) |

| Sensitivity management |

|

|

| Potassium nitrate |

Fills microscopic channels in exposed dentin, decreasing sensitivity to hot, cold, sweet, or sour foods and drinks |

Sensodyne Toothpaste (GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare) |

| Dry mouth control |

|

|

| Moisturizers/lubricants (e.g., glycerin, xylitol, sorbitol) |

Provides soothing, breath freshening; can be used several times each day |

Biotene Dry Mouth Oral Rinse (GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare) |

| Teeth whitening |

|

|

| Hydrogen peroxide/carbamide peroxide |

Used in teeth-whitening products |

Crest 3D White Whitestrips (Glamorous White; Procter & Gamble) |

| Sources: www.mouthhealthy.org (website of the American Dental Association Seal of Acceptance program); product websites. |

Toothbrushes and Dentifrices

The pathophysiologic processes that lead to caries, gum and gingival disease, and tooth loss all begin with biofilm developing in the mouth. If not removed regularly, this plaque builds up on the teeth. Within a day, plaque begins to calcify as tartar, or calculus. Anaerobic gram-negative organisms thrive in this biofilm and soon move into gingival and gum tissues, producing gingivitis and beginning the periodontal disease cascade (see Figure 3).18

Controlling plaque through physical removal is the foundation of home oral care; other steps the patient can take in plaque control include elimination or minimization of sugary, sticky foods; limiting sugary snack foods and sugary drinks between meals; and prevention or treatment of dry mouth symptoms. Removal of plaque begins with proper use of toothbrushes and various dentifrices.

Once thought to provide little advantage over manual toothbrushes, powered models are now recognized as removing more plaque and reducing gingivitis in the short and long term. Still unproven, however, is whether this greater efficiency translates into clinically important differences in oral health.38 For children and older patients with limited dexterity and those who are disabled, powered toothbrushes may offer distinct advantages: They require less movement of the wrist joint and have larger handles that are easier to grasp; the rapid rotation of the toothbrush head is more effective in removing plaque. Many powered toothbrushes also have a built-in timer that encourages longer brushing time and may serve a motivational purpose. In older patients, it is best to introduce use of an electric toothbrush before the onset of cognitive decline, as learning to use one can become challenging and sometimes frightening in those with dementia.

Powered toothbrushes are marketed with battery-operated and rechargeable features. Initial costs of rechargeable models are higher, but these devices avoid the long-term costs of batteries and maintain consistent effectiveness. The cost of replacement brushes for powered models is about twice that of new manual toothbrushes.

Both manual and powered toothbrushes have a variety of styles, handles, bristle composition (nylon or natural) and stiffness (extra soft, soft, medium, hard), and head sizes. Soft or extra soft bristles are recommended for most if not all individuals to allow cleaning at the gum line while avoiding tooth abrasion and soft tissue irritation; patients should follow the recommendations of their dental professional when specific features are needed.

For those requiring assistance with oral hygiene, caregivers typically use brushes with small heads that allow them to maneuver in the limited space of the oral cavity. A second brush may be used to prop open the mouth of a patient with limited cognitive function. The patient's lips should be lubricated beforehand, preferably with water-soluble products; petroleum-based lubricants can break down the material in gloves worn by the caregiver.39

With a toothbrush selected, the consumer must then choose an appropriate dentifrice. Toothpastes (which can be pastes, gels, or powders) generally contain mild abrasives such as calcium carbonate or silicates, fluoride, humectants that prevent water loss (glycerol, propylene glycol, or sorbitol), flavoring agents (including saccharin or other sweeteners), thickening agents (gums or colloids), and detergents (usually sodium laurel sulfate [SLS] or its derivatives).37,40

The American Dental Association (ADA) recommends that adults use a paste or gel containing fluoride. Applying fluoride to the teeth during brushing strengthens the enamel and reduces caries.40

Discussed in more detail in the mouth rinse section below, dry mouth can be managed with dentifrices formulated to moisturize the mouth, provide lubrication, and avoid harsh ingredients such as alcohol and SLS. If fluoride rinses are also needed, patients can alternate fluoride rinses with products for dry mouth at different times of the day.

Adults with gum recession or periodontal conditions may need a product that protects sensitive teeth from abrasives in toothpaste that are too rough for the exposed dentin and cementum layers. Toothpastes for sensitive teeth use less abrasive cleaners. They also contain potassium nitrate and other minerals that block microscopic tubules in exposed dentin; these are responsible for sensitivities to hot, cold, acidic, and sweet foods. Some toothpastes for sensitive teeth may have a different source of fluoride than regular fluoridated toothpastes (e.g., sodium fluoride rather than stannous fluoride) and substitute a gentler detergent for SLS.37,40

When tooth sensitivity is not adequately managed by desensitizing toothpastes, pharmacists should refer patients to dental professionals who can make sure symptoms are not caused by cavities or defective restorations.

Patients with sensitivity because of exposed roots or tooth decay may experience pain and discomfort when using whitening products. At a minimum, these patients should be evaluated by a dentist before attempting to whiten the teeth. Patients considering use of dentifrices that make whitening and/or tartar control claims should check for the ADA Seal of Acceptance, which indicates that ADA has reviewed these and other claims made on the product label and confirmed they are supported by adequate scientific evidence. They should also remember that whitening will not change the color of fillings or crowns, and some stains are not removed by whitening.40

Healthy gum tissue does not bleed during normal brushing and flossing. If patients report bleeding, pharmacists should recommend they see a dental professional while continuing oral hygiene (brushing twice a day and flossing once daily and the use of mouth rinses, or other recommendations made by oral health professionals) in the interim.

Dental Flosses and Related Devices

Plaque can also develop between teeth. Daily removal using dental floss or other interdental cleaners is just as important as brushing the rest of the tooth. Without plaque removal, gum tissues may become inflamed and caries can develop.

Most dental floss is made of nylon strands that have been stretched to decrease breakage. Patients with tightly spaced teeth should use waxed floss or products made from polytetrafluorethylene. Woven floss is useful as it facilitates pick up and removal of bacteria from tooth and gum surfaces. Product features such as mint or other flavors, or thicker or thinner strands, are personal preferences.

A variety of devices are also available for cleaning between the teeth. Adults with limited dexterity may be better able to clean interdental spaces with reusable and disposable floss threaders or powered devices that use high-pressure water to remove food particles and the plaque biofilm. Specially shaped interdental brushes or wooden toothpicks may also useful as a replacement for or supplement to dental floss.

The tongue also needs regular cleaning to minimize halitosis, or bad breath. A number of different styles of tongue cleaners are available in pharmacies or from dental professionals.

Mouth Rinses

Mouth rinses, marketed in an array of choices, contain many of the same ingredients as dentifrices (see Table 2). Products differ in their fluoride content, antimicrobial actions, alcohol content, and usefulness for xerostomia.

Fluoridated mouth rinses offer an additional dose of protection in those at high risk of dental caries. Several nonprescription products are available; dental and other health professionals can prescribe more concentrated fluoride formulations for patients at higher risk.

Mouth rinses that provide antiseptic actions are useful in reducing bacterial counts in the mouth and freshening the breath. Cetylpyridinium chloride is the most common antibacterial ingredient; overuse of these mouthwashes can lead to minor tooth staining or taste alterations. Many mouth rinses also contain high concentrations of alcohol (up to 27%) to enhance antibacterial action. Because oral exposure to alcohol has been associated with development of oral and upper gastrointestinal cancers, its presence in mouthwash has been questioned for decades. A recent study counters the assumption that alcohol in mouthwashes increases the risk of oral cancer, showing no association with use in general and no pattern of increasing risk with greater daily use.41

Alcohol-containing mouth rinses present in homes with small children create a risk for alcohol poisoning; most of these products have childproof caps for this reason and should be stored where children cannot reach them. Long-term care facilities may restrict access to these mouthwashes so that patients with dementia do not ingest them.

Those with dementia or who have had a stroke can have problems with pocketing food following meals (food getting stuck in the buccal pouches or other tight spaces in the mouth). These persons should rinse their mouths after each meal, and those with dentures should remove the dentures and rinse them off after each meal.

Given the strong relationship between dry mouth symptoms and increased number of dental caries, management of xerostomia is important in older patients and others with increased risk factors for caries or periodontal disease. Similar to the dentifrices discussed above, mouthwashes for dryness are specially formulated to moisturize and lubricate oral soft tissues and avoid ingredients such as alcohol and strong flavorings that can irritate the mouth. Mouth rinses for dry and sensitive mouths can be used up to five times a day; the effects of some formulations last up to 4 hours.

Care of Dentures and Implants

Patients who have lost many or all of their teeth likely have had poor oral hygiene habits for many years. Motivating them to incorporate an oral hygiene routine for partial or full dentures and implants into their daily schedules can be challenging. Yet that is exactly what is needed when these expensive prostheses are placed. Without proper care of the artificial teeth and attention to maintaining the health of the supporting soft and hard tissues, this expense and effort may be for naught. As in those with teeth, the tongue needs regular cleaning to minimize halitosis; tongue cleaners are available from dentists and pharmacies.

Dentures are prosthetic devices for replacing some or all of the natural teeth. They are made to fit precisely in a patient's mouth and conform to the remaining ridges of bone and gum tissue. Some dentures may be attached to implants embedded in this ridge and anchored in the upper or lower jawbones. Fixed or removable partial dentures ("bridges" or "partials") are supported by one or more natural or man-made abutment teeth.42

Implants for individual teeth can be anchored as shown in Figure 4. Partial and full sets of dentures can be implanted using a similar method where the prosthesis attaches to a base implanted into the gum and supporting bony structures. Upper or lower full or partial dentures attached in this way should be removed and cleaned as described below for traditional dentures. Nonremovable prostheses require care along with the remaining natural teeth as directed by a dental professional.43–47

Figure 4. Replacement of a natural tooth with an implant

|

The care of removable dentures employs different devices and products but requires the same cleaning regularity as natural teeth. To remove food, stains, and plaque, dentures should be brushed twice daily with a denture brush and minimally abrasive denture cleaners or mild soap and water. Brushing can be followed by soaking the dentures in marketed solutions that contain alkaline peroxide, hypochlorite (bleach), or dilute acids for the length of time given in product instructions. Patients who lack the manual dexterity needed for brushing can choose to soak the dentures in alkaline peroxide solutions overnight, but physical brushing is the preferred way to remove plaque and debris. Regardless of the cleaner used, patients must diligently remove the cleaner solution from the dentures before reinserting them to avoid gum irritation. The prosthesis can then be rinsed with water or nonalcoholic antimicrobial mouth rinse. The patient can rinse the mouth with an antimicrobial mouth rinse for 30 to 60 seconds before reinserting the denture.48

Those with dementia or who have had a stroke can have problems with pocketing food following meals. These persons should rinse their mouths after each meal, and those with dentures should remove the dentures and rinse them off after each meal.

During the period immediately following initial denture placement, patients may require additional maintenance procedures as directed by the dental team while the mouth adapts to the prosthesis and adjustments are made to obtain the best fit possible. However, even with well-fitting prostheses, some denture users may also need denture adhesives to help with retention, especially if there is little remaining bone support, when there is difficulty controlling dentures due to neuromuscular limitations or disorders, or over time if patients lose weight or have other events that affect the fit of the dentures. If adhesives are used, it is important that they be thoroughly removed from the dentures and mouth each day and then reapplied using the least amount necessary.

In long-term care facilities, staff need to be informed that the patient is wearing dentures, and in-service training programs should inform staff in how to appropriately clean dentures, and how to remove and insert dentures from residents' mouths. Losing or misplacing dentures in these facilities can be an especially vexing problem, given the lack of mental acuity of many residents.

CONCLUSION: ROLE OF THE PHARMACIST

The recognition of an important link between oral health and overall well-being of patients is growing. As dentistry seeks to break down the barriers that have historically separated it from medicine and other health professions, pharmacists will need to take on a greater role in helping patients maintain their oral health, counsel and educate patients as well as caregivers in the community and other health professionals in institutions to recognize the importance of daily oral hygiene throughout the lifespan, and encourage regular check-ups and cleanings by dental professionals.

Expanded roles for pharmacists could develop as the interprofessional movement proceeds and demand grows for an oral health benefit for older adults. Education and training will be needed for pharmacists to be ready to provide direct patient care services in the oral health realm.

Oral health care is a natural complement to medication therapy management services in patients with systemic diseases such as diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease, and in older adults with numerous diseases requiring several medications. By mastering the information in this continuing education program and seeking further education and training, pharmacists will be ready to take on expanded roles and help patients to enjoy long, active lives with a healthy mouth and a healthy body.

RESOURCES

Mouth Healthy: Consumer-facing website of the American Dental Association (www.mouthhealthy.org)

Smiles for Life: Resources useful for professionals in teaching students in the health professions or interacting directly with patients about oral health (www.smilesforlifeoralhealth.org)

Love the Gums You're With: Patient resources on the website of the American Academy of Periodontology (www.perio.org/consumer/patient-resources) and the organization's GUMBLR website for "all things gums" (www.loveyourgums.tumblr.com)

Mouth Care Without a Battle: An evidence-based approach to person-centered daily mouth care for persons with cognitive and physical impairment (www.mouthcarewithoutabattle.org)

Oral Health: Federal resources are listed on the Health Resources and Services Administration website (www.hrsa.gov/publichealth/clinical/oralhealth/)

Tooth Wisdom: Health resources, developed by the nonprofit Oral Health America, for older adults regarding the importance of oral health, finding dental care services, and paying for care (www.toothwisdom.org)

REFERENCES

- Murray C, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223.

- Haber J, Hartnett E, Allen K et al. Putting the mouth back in the head: HEENT to HEENOT. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):437–441.

- Slavkin HC, for the Santa Fe Group. A national imperative: oral health services in Medicare [editorial]. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(5):281–283.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- Li S, Williams PL, Douglass CW. Development of a clinical guideline to predict undiagnosed diabetes in dental patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(1):28–37.

- Dolan TA, Berkey D. Planning for the future. In: Friedman PK, ed. Geriatric Dentistry: Caring for Our Aging Population. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons; 2014:303.

- Luo HB, Pan W, Sloan F, Feinglos M, Wu B. Forty-year trends of tooth loss among American adults with and without diabetes mellitus: an age-period-cohort analysis. Preventing Chronic Dis. 2015;12:150309.

- American Dental Association. For the dental patient: diabetes and oral health. Available at http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/Files/patient_18.pdf?la=en. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- American Diabetes Association. Diabetes and oral health problems. Available at http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/treatment-and-care/oral-health-and-hygiene/diabetes-and-oral-health.html Accessed June 2, 2017.

- Avalere Health. Evaluation of the cost savings associated with periodontal disease treatment benefit. January 4, 2016. http://pdsfoundation.org/downloads/Avalere_Health_Estimated_Impact_of_Medicare_Periodontal_Coverage.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2017.

- Cohen LA. Enhancing pharmacists' role as oral health advisors. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53:316-321.

- Gulati M, Anand V, Jain N, et al. Essentials of periodontal medicine in preventive medicine. Int J Prev Medicine. 2013;4(9):988–94.

- Olsen I. From the acta prize lecture 2014: the periodontal-systemic connection seen from a microbiological standpoint. Acta Odontol Scand. 2015;73(8):563–8.

- Jeffcoat MK, Jeffcoat RL, Gladowski PA, Bramson JB, Blum JJ. Impact of periodontal therapy on general health: evidence from insurance data for five systemic conditions. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2):166-174.

- Nasseh K, Vujicic M, Glick M. The relationship between periodontal interventions and healthcare costs and utilization: evidence from an integrated dental, medical, and pharmacy commercial claims database. Health Econ. 2017;26(4):519-527.

- Jin LJ, Lamster IB, Greenspan JS, Pitts NB, Scully C, Warnakulasuriya S. Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis. 2016;22(7):609–619.

- Gregory D, Hyde S. Root caries. In: Friedman PK, ed. Geriatric Dentistry: Caring for Our Aging Population. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014:97.

- Gupta S. Periodontal disease. In: Friedman PK, ed. Geriatric Dentistry: Caring for Our Aging Population. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014:107–115.

- Dye BA, Thornton–Evans G, Li X, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;197.

- Wu B, Liang J, Plassman BL, Remle RC, Bai L. Oral health among white, black, and Mexican-American elders: an examination of edentulism and dental caries. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(4):308–17.

- Kandelman D, Petersen PE, Ueda H. Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Spec Care Dentist. 2008;28(6):224–236.

- Zhang W, Wu YY, Wu B. Does oral health predict functional status in late life? Findings from a national sample. J Aging Health. 2017 Mar 20:898264317698552.

- Kassab MM, Cohen RE. The etiology and prevalence of gingival recession. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:220–225.

- Hjerstedt J. Xerostomia. In: Friedman PK, ed. Geriatric Dentistry: Caring for Our Aging Population. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014:152.

- Lalla RV, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Antifungal medications or disinfectants for denture stomatitis. Evid Based Dent. 2014;15(2):61-62.

- Emami E, Kabawat M, Rompre PH, Feine JS. Linking evidence to treatment for denture stomatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Dent. 2014;42(2):99–106.

- Institute of Medicine. Advancing oral health in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

- The Gerontological Society of America. Oral health: an essential element of healthy aging. Accessed at https://www.geron.org/images/gsa/documents/oralhealth.pdf, June 2, 2017.

- Mann RS, Marcenes W, Gillam DG. Is there a role for community pharmacists in promoting oral health? Br Dent J. 2015;218:E10.

- Romoa CP, Eissenberg T, Sahingur SE. Increasing popularity of waterpipe tobacco smoking and electronic cigarette use: implications for oral healthcare. J Periodontal Res. 2017 Apr 10. doi: 10.1111/jre.12458. [Epub ahead of print]

- Rogers SN, Lowe D, Catleugh M, Edwards D. An oral cancer awareness intervention in community pharmacy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;48(7):498–502.

- Taing MW, Ford PJ, Gartner CE, Freeman CR. Describing the role of Australian community pharmacists in oral healthcare. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24(4):237–246.

- Levy JM, Abramowicz S. Medications to assist in tobacco cessation for dental patients. Dent Clin North Am. 2016;60(2):533–540.

- American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–46.

- Khan M, Cheung AM, Khan AA. Drug-related adverse events of osteoporosis therapy. Endocrin Metab Clin North Am. 2017;46(1):181–192.

- Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw, Yoneda T, Hagino H et al. Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Position Paper 2017 of the Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. J Bone Miner Metab. 2017;35(1):6–19.

- Hitz Lindenmuller I, Lambrecht JT. Oral care. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2011;40:107–115.

- Yaacob M, Worthington HV, Deacon SA, et al. Powered versus manual toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD002281.

- Wener ME, Yakiwchuk C-A, Bertone M. Promoting oral health care in long-term care facilities. In: Friedman PK, ed. Geriatric Dentistry: Caring for Our Aging Population. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014: 266.

- American Dental Association. Learn more about toothpastes. Available at http://www.ada.org/en/science-research/ada-seal-of-acceptance/product-category-information/toothpaste. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- Gandini S, Negri E, Boffetta P, La Vecchia C, Boyle P. Mouthwash and oral cancer risk quantitative meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19(2):173–180.

- Ettinger RL. Prosthetic considerations for frail and functionally dependent older adults. In: Friedman PK, ed. Geriatric Dentistry: Caring for Our Aging Population. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014:179.

- Lyle DM. Implant maintenance: is there an ideal approach? Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013;34(5):386–390.

- Apatzidou DA, Zygogianni P, Sakellari D, Konstantinidis A. Oral hygiene reinforcement in the simplified periodontal treatment of 1 hour. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(2):149–156.

- Magnuson B, Harsono M, Stark PC, Lyle D, Kugel G, Perry R. Comparison of the effect of two interdental cleaning devices around implants on the reduction of bleeding: a 30-day randomized clinical trial. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013;34 Spec No 8:2–7.

- American Dental Association. Dentures. ADA Patient Smart Patient Education Center. Available at http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Publications/Files/ADA_PatientSmart_Implants.ashx. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- American Dental Association. ADA Patient Smart Patient Education Center. Dental implants. Available at http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Publications/Files/ADA_PatientSmart_Dentures.pdf?la=en. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- Wingrove S. Focus on implant home care: before, during, and after restoration. Registered Dental Hygienist. 2013(9). Available at http://www.rdhmag.com/articles/print/volume-33/issue-9/features/focus-on-implant-home-care.html. Accessed June 2, 2017.

Back to Top