Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Implementing and Providing Transitions of Care Among Health Care Settings

INTRODUCTION

Transitions of care (TOC) is a term that refers to movement of patients among health care practitioners, settings, and home as their condition and care needs change.1 For example, a patient requiring hip surgery may be referred from his primary care provider (PCP) for evaluation at an outpatient orthopedic surgery clinic and then transitioned to a hospital. After surgery, the patient may be discharged to a skilled nursing facility for rehabilitation, and then return to his PCP for follow-up.

Poor TOC create considerable cost in the United States. About 18% of Medicare hospital admissions result in readmissions within 30 days of discharge, accounting for $15 billion in spending.2 Of that amount, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission found that Medicare spends about $12 billion on potentially preventable readmissions.2 Medication-related issues such as cost barriers, poor understanding of how to take medications correctly, and serious adverse drug events (ADEs) resulting from lack of medication reconciliation can contribute to hospital readmissions. These are TOC issues.

Because of our health care system’s infrastructure, patients often encounter fragmented care when moving between health care settings.1 Clinicians often discharge patients without assessing their ability to care for themselves. Minimal information on discharge instructions, rushed education, and false assumptions that the next provider of care will assume responsibility for further management break the system down further. To improve overall quality of care, the federal government instituted the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. It imposes financial penalties on hospitals with excessively high readmission rates for Medicare patients.

The Joint Commission (TJC) has outlined methods to optimize patients’ transition between health care settings.1 Root causes for ineffective TOC include

- Communication breakdown: Care providers often keep information among themselves or within silos, and exchange information between settings poorly.1 The Center for Transforming Health Care’s Handoff Communication Project highlights several risk factors that promote this breakdown in communication3:

- Culture does not promote successful handoff (e.g., lack of teamwork and respect).

- Expectations between the communication initiator (sender) and receiver differ.

- The sender uses ineffective communication methods (e.g., verbal, recorded, bedside, written) and provides inaccurate or incomplete information, which may include medication lists, concerns/issues, and contact information. This contributes to duplicate prescriptions and increases risk for drug-drug interactions.

- The team does not synchronize timing of physical transfer of the patient and the handoff.

- The team lacks standardized procedures describing successful handoff.

- Lack of accountability and care coordination: Each provider may treat only 1 aspect of a patient’s care without regard to other providers’ treatment.2 Providers may focus on acute needs as opposed to holistic and patient-centered needs. Poorly coordinated care between multiple providers may result in patient confusion, over-treatment, duplicate services, higher spending, and lower quality care.2

- Patient education breakdown: Patients and caregivers may be excluded from planning related to the transition process.1 They may receive conflicting recommendations, confusing medication regimens, and confusing instructions about follow-up care, which can lead to poor medication adherence.

FINDING MODELS THAT WORK

Since the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010, many TOC models have emerged to reduce readmissions (Table 1). One successful model is described in a randomized controlled trial, The Care Transitions Intervention.4 This study was conducted in a large institution in Colorado and targeted the community-dwelling residents aged 65 years or older admitted to the study hospital with 1 of 11 selected comorbidities. The researchers recruited 750 patients between September 1, 2002, and August 21, 2003. They randomized patients to receive the study intervention or usual care. The care intervention activities were based on pillars (conceptual domains identified from patient feedback identifying things that would be valuable to them):

- Assistance with medication self-management

- Patient-centered record owned and maintained by the patient to facilitate cross-site information transfer

- Timely follow-up with primary or specialty care

- A list of red flags indicative of a worsening condition and instructions on how to respond to them

| Table 1. Models for Transitions of Care |

| Project |

Aims |

Setting |

Quality Improvement Resources and Tools |

Outcomes |

| Care Transitions Intervention (CTI or the Coleman Model) |

Advanced practice nurse as a "transitions coach"

• Facilitate patient and caregiver's roles in self care

• Medication review and reconciliation using the Medication Discrepancy Tool via telephone calls or home visits within 48 to 72 hours after hospital discharge, for a total of 3 times during a 28-day post hospitalization discharge period |

Hospital to:

• Home

• Home with home health

• Skilled nursing facility |

Medication Discrepancy Tool (MDT)11:

• Categorizes the types of medication discrepancies at the level of the delivery system (inclusive of the prescriber) as well as the level of the patient

• Discrepancies identified include an explanatory factor. For example, a system level discrepancy may result from poor or illegible instructions provided by the health care provider to the patient. Patient-associated discrepancies were classified as intentional vs nonintentional nonadherence. The former refers to a situation when medications were recommended by a prescribing clinician but chooses not to follow this advice. The latter refers to a situation when a patient did not know what medications were prescribed and therefore adherence was not a matter of choice. |

Lower 30-, 90-, and 180-day readmission rates postdischarge Significantly lower hospital costs at 90 and 180 days postdischarge |

| Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions (BOOST) 9 |

• Identify patients at high risk of re-hospitalization and target specific interventions to mitigate potential ADEs.

• Reduce 30-day readmission rates

• Improve patient satisfaction scores and H‐CAHPS scores related to discharge

• Improve flow of information between hospital and outpatient physicians and providers

• Improve communication between providers and patients

• Optimize discharge processes |

Hospital to home |

Risk Assessment – 8P method to identify risk factors that need to be addressed for all hospitalized patients |

Best practices will be collected from participating programs to develop national standards |

| Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) 10 |

Readmission reduction program |

Hospital to home |

12 components, including identifying a need for and obtaining language assistance, making appointments for follow-up care and planning for follow-ups of test or lab results pending at discharge. |

Lowered readmissions and post-hospital emergency department visits. |

| STate Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) 11 |

To reduce rehospitalizations by working across organizational boundaries and engaging payers; stakeholders at the state, regional and national level; patients and families; and caregivers at multiple care sites and clinical interfaces. |

Hospital to home |

STAAR readmissions diagnostic worksheets and a tool for State Policy Makers |

The Institute for Healthcare Initiatives (IHI) applies STAAR resources to participating states and measures impact on readmissions, patient experience, # admissions to observation status per month, and percent of TOC processes completed per patient |

| Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) 12 |

To improve care and reduce the frequency of potentially avoidable transfers to the acute hospital. Such transfers can result in numerous complications, and billions of dollars in unnecessary health care expenditures. |

Skilled nursing facility, assisted living facility, or any long-term care facility |

Tools for early identification, assessment,

documentation, and communication about changes in the status of residents in

skilled nursing facilities. These tools include communication tips within the nursing home, and between nursing home and hospital setting |

50% reduction in the overall rate of hospitalizations during the 6-month intervention period compared to baseline. The proportion of hospitalizations rated as potentially avoidable was also reduced by 36%—from 77% at baseline to 49% during the intervention. |

Patients were assigned transition coaches—advanced practice nurses who helped facilitate each patient’s and caregiver’s role in self-care, and who encouraged them to do as much as possible independently. Transition coaches provided interventions, following patients during their hospital stay, making postdischarge home visits, and placing follow-up telephone calls. Rehospitalization rates were measured at 30, 90, and 180 days. This study found that patients in the intervention arm had lower rehospitalization rates at 30 days (8.3 versus 11.9, P = 0.48) and at 90 days (16.7 versus 22.5, P = 0.04) than control subjects. Intervention patients also had lower rehospitalization rates for the same condition at 90 days (5.3 versus 9.8, P = 0.04) and at 180 days (8.6 versus 13.9, P = 0.046). The study concluded that coaching chronically ill older patients and their caregivers to ensure their needs are met during care transitions may reduce subsequent rehospitalization rates.

In 2006, almost 1 in 4 Medicare beneficiaries discharged from the hospital to skilled nursing facilities (SNF) were readmitted within 30 days at a cost of $4.3 billion.5 Congress passed the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT Act) that establishes a quality reporting program for SNFs. Failure to comply with data submission requirements will result in reduced payment penalties beginning fiscal year 2018.6 An increasing amount of literature has been published concerning hospital pharmacist involvement in SNF transitions. Many of these projects are equipped with quality improvement tools that promote patient safety and are customizable to meet individual programs’ needs.

Lapses in communication among facility staff along with documentation and transcription errors have led to poor coordination of care. Studies have demonstrated that information on discharge summaries differs from that on transfer/referral forms in more than 50% of long-term care admissions, and 70% of all admission records contain at least 1 medication discrepancy. Up to 60% of these errors have been serious, life-threatening, or fatal. Errors involved in transitions from hospitals to long-term care (LTC) facilities may be more likely to cause harm to patients; they often involve high-alert medications including warfarin, insulin, opioids, and cardiovascular medication. ISMP recognizes that pharmacists can help identify omitted medications, non-indicated medications, and dosing errors. Pharmacists can reconcile medications and note discrepancies, provide reasons for changes to medications, and verify the accuracy of discharge summaries.7

One hospital launched a quality-improvement project that focused on developing a standardized discharge order reconciliation process that included a clinical pharmacist. After the hospital-wide implementation of the new workflow, the readmission rate for SNF patients decreased from 9.5% to 6.7%.8

Another group randomly reviewed electronic medical records and paper chart medication reconciliation lists across 3 transitions of care: hospital admission to discharge (time 1), hospital discharge to SNF (time 2), and SNF admission to discharge home or LTC (time 3).9 A principal investigator and a pharmacist identified and categorized medication discrepancies in 132 TOC involving 1,696 medications. Discrepancies were defined as any documented but unexplained change in the patient’s medication lists between sites. Unintentional discrepancies were defined as any omission, duplication, or failure to change back to the original regimen when indicated. More than 300 discrepancies were identified at each transition point, and 86% of patients had at least 1 unintentional discrepancy in their records. On average each patient had 8.1, 7.2, and 7.6 discrepancies at times 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This study demonstrated the widespread prevalence of medication discrepancies in these settings, emphasizing the role for pharmacists to protect patients from medication-related harm during vulnerable transitions.

Furthermore, pharmacists can play an integral role in hands-on medication management during postdischarge home visits. One study evaluated the value of health information technologies by managing medication regimens using an electronic personal health record (ePHR) coupled with a pharmacist visit to recently discharged patients' homes.10 Usual care consisted of medication reconciliation at discharge provided by hospital clinicians, but no subsequent home visits from pharmacists. Pharmacists were more likely to detect medication-related problems among patients who agreed to use the ePHR than in patients who declined the ePHR. Though this study’s sample size was too small to conclude a statistically significant impact, the results suggest that pharmacist home visits following a hospitalization can help identify medication-related problems. The ePHR can enhance the pharmacist’s assessment and allow patients to share their medical information readily with other health care providers. Many companies offer programs that tailor medication management solutions for TOC.

Inpatient and Outpatient Transitions of Care

In addition to inpatient hospital-to-home TOC practices, a number of outpatient interventions can be implemented to improve a health-system’s TOC. If a hospital is associated with its own hospital-based clinics and/or medical practices, then it can place pharmacists and other specialized personnel (such as behavioral health experts, social workers, and health education specialists) in clinics to develop a patient centered medical home (PCMH). The PCMH concept is not new. In fact, most customer service models in the business world provide services that revolve around the person receiving the service.

Use of this concept in health care has shifted the way that medicine is practiced and significantly improved patient care. The Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC) has based its entire TOC service around ensuring a smooth transition back to the community setting, thus preventing many readmissions.17 The PCPCC program, an example of a discharge or ambulatory care intervention, suggests 2 actions are crucial to good transition processes: connecting patients to their PCP immediately and providing services such as medication reconciliation and follow-up on hospital orders.

Bedside Education and Access to Medication

In 2014, the University of California Davis Medical Center (UCDMC) augmented its TOC interventions to improve patient outcomes. First, it added a bedside medication delivery service known as BEAM (Bedside Education and Access to Medication) to the TOC service. Pharmacists used the teach-back method at bedside to provide basic TOC service:

- Admission and discharge medication reconciliation

- Assessment of barriers to medication access (e.g., medication insurance, cost, and transportation)

- Personalized medication counseling

The BEAM service enhanced TOC by delivering discharge medications to each patient’s bedside to supplement the counseling.

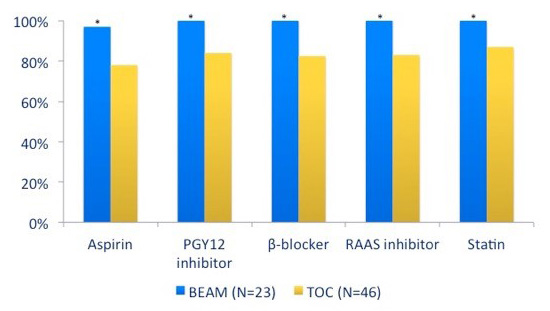

During BEAM implementation, a postgraduate year 2 pharmacy resident conducted a single-center, prospective study of patients admitted to the cardiology unit for an acute myocardial infarction (AMI)–related event receiving TOC only, BEAM intervention (TOC + Bedside Delivery), or usual care (discharged without TOC or BEAM). The primary outcome measure was medication initiation rate, which was defined as AMI medications dispensed on day 1 of the potential 30-day readmission cycle. The secondary outcome measure was 30-day hospital readmission rate.

The results were impressive. All patients in the BEAM group received their medications on the day of discharge (day 1). Eighty percent of patients in the TOC-only group received their medications on day 1 (Figure 1). The differences were significant when considering that both groups received all other aspects of the TOC service. Despite thorough medication reconciliation and medication education, high-risk patients who did not receive BEAM were still discharged without all required medications 20% of the time.

| Figure 1. Medication initiation rates on day 1 of hospital discharge. |

|

Source: Reference 18.

Abbreviation: RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. |

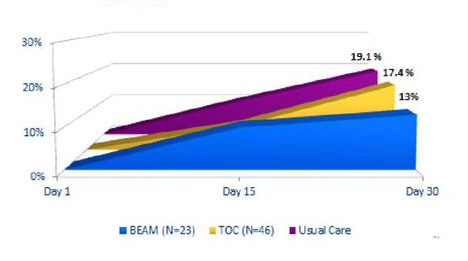

The data also addressed readmissions. Patients receiving usual care had a baseline 30-day readmission rate of 19.1%. Readmission rates when 17.4% when TOC pharmacy services were provided (n = 46), and further decreased to 13% in the BEAM intervention group (n = 23) (Figure 2). The results of this study led the hospital to continue the bedside medication delivery service.18

| Figure 2. Rehospitalization rates at 30 days postdischarge for Bedside Education and Access to Medication (BEAM), transitions of care (TOC), and usual care groups. |

|

| Source: Reference 18. |

UCDMC's Second Intervention

UCDMC’s second TOC intervention was the development of a PCMH model that included a pharmacist. This model allowed TOC pharmacists in the hospital to handoff patients to a primary care team. The outpatient PCMH pharmacist would then follow up on medication issues that were unresolved during hospitalization. Examples include Medicare Part D plan restrictions, copayment assistance, and patient assistance programs (PAPs).

For Medicare Part D coverage problems, PCMH pharmacists worked with patients during open enrollment face-to-face in a clinic setting or by telephone to help them choose plans that would cover their medications. Choosing a Medicare Part D plan and applying for low income subsidies for extra financial help requires the use of an online plan finder, which nontech-savvy patients can find difficult to navigate. Patients eligible for copayment assistance programs and PAPs benefited from enrollment; pharmacists helped patients receive long-term medications without interruption if cost was a major barrier. Enrolling in Medicare Part D or PAPs take time and requires direct patient involvement, which can be difficult during a hectic discharge. The use of pharmacy technicians and/or other expanders can create further efficiencies during TOCs.

Adding Motivational Interviewing

Even when patients receive accurate medication lists with thorough discharge education, they remember only 40% to 80% of medical information given to them.19 This can lead to patient medication administration errors and readmissions. PCMH pharmacists provide additional and repeated education to patients to promote a deeper understanding of their medications and how to take them. They employ motivational interviewing (MI) strategies to help patients reach their health goals. MI involves listening to patients describe their desired objectives and applying techniques to show them how taking better care of themselves will achieve these goals. Examples of health goals include increasing exercise and mobility. A provider could use this goal to manage patients’ uncontrolled diabetes better by educating them about the risks of developing peripheral neuropathy resulting in possible limb removal. Other examples include

- Promoting medication adherence to prevent hospitalization

- Changing the timing of medications to help target symptoms

- Empowering patients to be in better control of their role in medication management

Each of these situations has occurred at UCDMC since the program started in 2014, and at the time this article was prepared, expansion of these services to clinics that lack a pharmacist was under consideration. Along with studies showing the value of patient-centered discharge instructions and follow-up phone calls, these outcomes show that TOC interventions are as important after patient discharge as they are during the patient’s hospitalization.20

Transitions of Care in Specialty Departments

A third UCDMC program is the expansion of pharmacy roles in specialty departments. UCDMC’s specialty pharmacists provide a hybrid of inpatient and outpatient contact with patients. Patients seen in specialty clinics such as hepatology, neurology, and transplant are assigned to a specialty pharmacy team of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. These teams ensure that patients receive patient-centered care with a focus on medication adherence. The specialty pharmacy team identifies patients at high risk for readmission upon discharge. They enroll patients in high intensity follow-up programs that aim to prevent hospital readmission. Adherence tools, intensive education about diseases, and 24/7 access to their personal specialty pharmacy team help patients achieve their goals.

Pharmacy staff calls patients frequently to verify that they are taking their medications on schedule, completing their required labs on time, and answer questions or discuss potential adverse effects. One tool that can be used to determine medication adherence is the Morisky scale.21 Pharmacy staff asks patients a series of questions that determine the likelihood that a patient will have trouble with medication adherence. The team then uses this information to gauge the amount of follow-up and connection the patient needs to ensure positive outcomes. If a patient is admitted to the hospital, the specialty team coordinates care with the inpatient team. Together, they ensure that drug dosing is correct and the patient is able to obtain high-cost medications. They also identify rare drug-drug interactions that may be overlooked involving infrequently used specialty drugs and biologics.22

Community-Based Transitions of Care

TOC also occurs in community pharmacy settings. Pharmacists in these settings have restructured their usual product-focused operations to include methods to improve patient medication adherence, provide medication therapy management (MTM), and offer bedside delivery to nearby hospitals that may lack internal pharmacies.

One example is the WellTransitions program initiated by Walgreens in 2012.23 Poor medication adherence rates are highly correlated with early readmissions. Walgreen’s pharmacists and pharmacy technicians obtain access to the patient’s hospital medication list. They provide MTM services and deliver the patient’s discharge medications to the bedside before discharge.24 Currently, the WellTransitions program provides bedside delivery services to more than 100 hospitals. In some cases, Walgreens pharmacists telephone patients to check for problems that may arise during the critical 30-day post discharge window. These services have shown some initial improvement in patient satisfaction rates and are an option for hospitals that lack internal pharmacy support.

Other community pharmacies have joined the effort. Kroger began TOC services in Cincinnati, OH, to decrease readmissions for high risk patients. Pharmacies in Wisconsin also offer discharge medication reconciliation as a method to decrease medication errors and readmissions.25,26 Sen et al. found that a collaboration between Mercy Hospital and SunRay community pharmacy that included bedside delivery, 72-hour postdischarge telephone calls, and comprehensive medication management (CMM, which includes medication reconciliation and medication action plans) decreased readmission rates at their hospital.27 Some hospitals have begun to support integration of social services into the health care team to improve readmissions. New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation invested in transitional housing for their highest risk patients. It reports dramatic improvements in readmission rates, emergency department (ED) visits, and overall cost.27

FOUNDATIONS TO ENSURE SAFE TRANSITIONS OF CARE

Whether TOC interventions are provided within the hospital, ambulatory clinic, or outsourced to nearby pharmacies, TOC efforts are everywhere. Hospitals that do not implement a service will have a hard time competing in the new value-based environment. TJC recommends that all institutions establish 7 foundations to ensure safe transitions between health care settings29:

- Medication management

- Transitional planning

- Early identification of patients/clients at risk

- Patient and family action/engagement

- Leadership support

- Multidisciplinary collaboration

- Transfer of information

Medication Management

TJC has established medication reconciliation as a national patient safety goal. TJC does not specify who “owns” medication reconciliation but suggests that the process is multidisciplinary and should involve pharmacy. Medication reconciliation involves obtaining the best possible medication history (BPMH), which ideally extends across the continuum of care and becomes a standard practice for all health care settings. More comprehensive than a routine primary medication history, a BPMH involves 2 steps: obtaining a thorough history of all prescribed and nonprescribed medications using a structured patient interview and verifying this information.

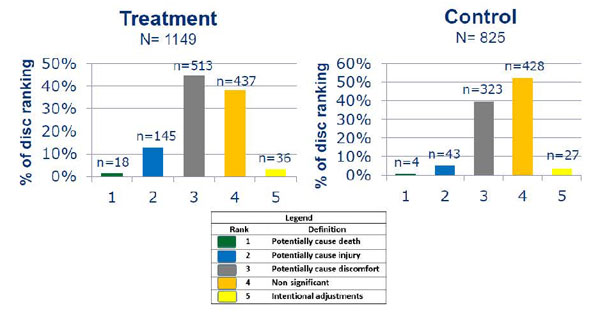

UCDMC conducted a pilot study, Reduce Medication Errors by Doing Early Medication Reconciliation in the Emergency Department (ED), from January 6 to January 23, 2014.30 The study evaluated the number of discrepancies found in patients who received medication reconciliation early in the ED (treatment group) and compared them with patients who received medication reconciliation after admission (control group). More patients in the control group (n = 173) received medication reconciliation than those in the treatment group (n = 134) but more discrepancies were discovered in the treatment group (383 discrepancies versus 275 discrepancies). In both groups, 97% of the discrepancies were unintentional, with the majority being medication omissions. An expert panel of 2 physicians and 1 pharmacist reviewed these discrepancies to rank their level of severity. They found that most discrepancies were of low severity although a few discrepancies could have potentially caused injury or even death (Figure 3). The investigators concluded that if admission orders are based on the prior to admission (PTA) medication list, errors are likely to occur during the patient’s hospitalization, emphasizing the importance of completing medication reconciliation at all transition points. The earlier this process is completed, the sooner discrepancies can be identified and addressed to prevent potential harm to the patient.

| Figure 3. Discrepancy rankings for treatment (transitions of care) and control groups. |

|

| Source: Reference 30. |

The Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) was a multisite mentored quality improvement (QI) study that assessed medication reconciliation QI interventions’ effects on unintentional medication discrepancies with potential for patient harm.31 It determined the most important components of a medication reconciliation program and detailed them the MARQUIS Implementation Guide. This guide is a valuable resource that compiles best practices for medications to be prescribed, recorded, and reconciled accurately at care transitions. The manual and its accompanying online resources provide enough detail for sites to adapt these concepts to their environments, recognizing that each site will have different strengths and weaknesses.

The MARQUIS tools offer videos, pocket guides, and tools on how to obtain a BPMH to ensure providers make informed decisions with accurate medication lists. A complete medication entry should include the medication’s name, formulation, dosage, route, and frequency. A medication list (if available) may supplement patient or caregiver interviews. However, medication lists are highly likely to be inaccurate depending on when they were updated. The interview should be conducted by asking open-ended questions, and clinicians should avoid reading the list to the patient.

If the patient is taking medications as needed (PRN), clinicians should ask how many times a week that medication is used and for what symptoms. They should also ask about recent changes to medications; over-the-counter products including herbs and supplements, samples; and other commonly forgotten medications such as inhalers, nebulizers, and creams. If the patient is a reliable historian, it may be unnecessary to gather additional data. However, if the patient is a poor historian (i.e., is unsure about medication names, doses, and indications or cannot provide medication information from memory), clinicians will need secondary sources.

Secondary verification sources include calling the patient’s pharmacy for a fill history, obtaining information from family members, and using original bottles or pill identifier tools if the patients brings medications in an unlabeled pill box. The medication reconciliation process is dynamic, and the patient’s medication list should be updated as new information becomes available. Once the medication list is as complete as possible, given the information available at the time of gathering, clinicians need to reconcile it by comparing it with currently inpatient orders and addressing discrepancies. They must assess the last dose taken, especially for medications with narrow therapeutic indexes, or if missing information is potentially dangerous or creates high risk of over-treatment or under-treatment (e.g., warfarin, insulin, immunosuppressive therapy, etc.). If any information is missing, clinicians may need to investigate further. This may include telling the primary provider if the patient reports taking medications differently than prescribed and providing patient education when needed. Clinicians should stress that patients should update their own medication lists as they move across the continuum of care, as they are the constant players at each transition.

Transitional Planning, Early Identification, and Action/Engagement

Discharge risk assessment should begin within 24–48 hours of admission and continue throughout the hospital stay. Risk factors include low literacy, recent hospital admission, multiple long-term medications, or poor self-health ratings. Clinicians should also assess barriers such as access to medications, transportation, financial shortcomings (e.g., lack of insurance or underinsured status), and caregiver availability. These need to be addressed before discharge.

To promote patient involvement in the discharge plan, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed a discharge planning checklist for patients and their caregivers preparing to leave a hospital, nursing home, or other care setting.32 The checklist outlines action items to prompt patients/caregivers to ask questions regarding health status, recovery plan, medication, and follow-up care.

In October 2015, CMS proposed new discharge planning requirements for hospitals that would require all hospitals and home health agencies to develop a written discharge plan for every inpatient and specific categories of outpatients within 24 hours of admission.33 With a written discharge plan, patients will be able to decide the location of their next site of care. The proposal includes a medication reconciliation process as part of the discharge plan. The final ruling had not been issued when this article was prepared.

LEADERSHIP SUPPORT

As tempting as it is to start a service within 1 area of the hospital (i.e., pharmacy department), it is unlikely to become a hospital-wide program without administrator buy-in. To provide sustainable TOC interventions that are likely to improve care and patient satisfaction, the health-system’s top administrators (i.e., the corporation's most important senior executives or “C-suite”) must invest in the program. Each available TOC or Med Rec toolkit—including Project RED, BOOST, and MARQUIS—mentions significant administrator buy-in as a key component to a successful program.12,13,34 The primary literature has shown the value of administrator buy-in with the subsequent development of a clear leadership structure in TOC interventions.35 Because this first step is often beyond the care provider’s control , it is seen as the most difficult aspect to achieve when creating a new TOC program.

There are many ways to justify implementing a TOC service within a health system. The first and most obvious is that TOC services should significantly improve patient care by decreasing the number of medication discrepancies that reach the patient. Beyond improving patient care, administrators specifically seek revenue-generating or potential cost-saving interventions that justify any new program’s cost. Fortunately, the amount of literature concerning TOC has increased appreciably in the last 10 years, providing ample avenues to take when presenting a proposal to corporate leaders.

Reducing ADEs

One of the more straightforward approaches is to determine the average cost of an ADE, and estimate the total cost of ADEs based on bed capacity and the ratio of average discrepancies per patient. This represents potential cost savings and money available for staffing if administration believes that TOC will prevent ADEs.

One study estimated a cost of $4800 per ADE.36 The National Quality Forum estimated that annual losses of more than $21 billion are attributable to preventable medication errors.37 These studies show the stark reality of a problem that was largely overlooked in previous decades.

Return on Investment

Another way to show improved financial performance is to calculate return on investment (ROI) for the proposed service. The MARQUIS tool provides examples of ROI calculations that estimate the potential annual net savings based on the need for additional staff and implementation of pharmacy TOC services.34 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists also has an interactive ROI tool that can be used to create a custom-made ROI for a TOC proposal.38

Reducing 30-Day Readmissions

In addition to the more straightforward ROI approach, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) began on October 1, 2012.39 This CMS program uses a complicated process to determine financial penalties for hospitals based on excessive readmissions for certain disease states. The penalties have increased each year, and CMS plans to add disease states as they move toward value-based care.

Administrators are aware of the HRRP and are actively looking for ways to keep patients from being readmitted. One paper described 4 interventions, each implemented by different hospitals, that could avoid $1 million in losses annually at each hospital.40 Interventions included medication reconciliation, patient education, bedside delivery, and development of clinics for high-risk patients. Because of the potential for acute financial loss, a proposal showing a TOC program’s potential to avoid penalties has more funding potential now than ever before.

Accountable Care Organizations, Value-Based Purchasing, and Patient Satisfaction

CMS hopes to tie 90% of Medicare reimbursements to value-based purchasing (VBP) or an accountable care organizations (ACOs) model by 2018.41 Even without the HRRP penalties, hospital administrators are looking for ways to improve patient care and improve the bottom line. They must prepare for a future in which funding models are based not only on best practices, but also on improved outcomes and stellar patient experiences.

CMS funded its first ACO Shared Savings demonstration project,42 giving participating hospitals the opportunity to share in joint savings with Medicare by providing safe, effective, and fiscally efficient care.

In addition, many hospitals have improved patient satisfaction scores by implementing TOC programs. Patient satisfaction is directly linked to reimbursement through value-based purchasing (VBP).43 VBP shifts the focus of billing from the care process to care outcomes, and includes a patient satisfaction element. With the 3 new Care Transitions Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers Score (HCAHPS) questions,44 1 of which directly relates to medication understanding at discharge, organizations have an incentive to implement TOC programs and include a pharmacy component.

Payment Models

In addition to the money being saved by keeping patients out of the hospital and/or improving outcomes, health systems can consider increasing revenue by billing. If a system has a PCMH system or an attachment to ambulatory care clinics in place, they can bill using transitional care management (TCM) codes.45 The TCM codes reimburse at higher rates per visit than standard evaluation and management (E/M) codes do. The most difficult element of using these codes has nothing to do with patient care but rather with how they are billed. Organizations must meet specific components to bill for this type of visit:

- These codes only apply to patients with moderate or high intensity needs upon discharge; each patient needs to be contacted within 2 days of discharge to qualify.

- Patients must be seen within 7 days (high-intensity patients) or 14 days (moderate-intensity patients) to bill the 99496 and 99495 codes respectively.

- Once all of the previous requirements are met, the patient must not be rehospitalized with 30 days of the initial hospitalization.

Because of the third point, bills cannot be submitted until the 30-day period has passed with no rehospitalizations.

Most hospitals process billing statements directly after the encounter occurs, with no regard to time since discharge. TCM requirements may challenge standard billing procedures as coders scramble to design systems that hold these bills until the proper submission time. Additionally, these bills can only be processed once and only by 1 provider. Therefore, health systems will need to determine which provider will use the TCM code and who will use standard E/M codes.

Ahough pharmacists cannot bill these visits independently, they are able to see patients in tandem with physicians. It is possible for pharmacists in the PCMH setting to see patients under these codes, provided that they work in concert with a physician in their practice area. Additionally, pharmacists can see patients for CMM services, and bill using MTM codes. These codes can be difficult to set up, but some pharmacists have billed using these codes for their more complex and/or older patients.46

MULTIDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATION AND TRANSFER OF INFORMATION

TJC reports that the need for collaboration is TOC’s greatest challenge. The National Transitions of Care Coalition (NTOCC) addresses this concern by providing a publically available compendium of online resources for patients, providers, payers, and policymakers who are interested in TOC and its challenges.47 The NTOCC Advisors Council has created 4 work groups to address key areas including education and awareness, tools and resources, performance measures, and policy and advocacy. In addition, NTOCC has a taskforce dedicated to Health Information Technology Innovations that address gaps in TOC issues such as transfer of information between settings.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare has also continued efforts to improve the health information exchange by creating a Handoff Communications Targeted Solutions Tool. This tool is a model for launching handoff communications performance improvement projects within health care organizations.

A total of 53 CMS-funded quality improvement organizations (QIOs) are taking progressive steps to provide a robust set of resources that can be shared among community coalitions consisting of hospitals, nursing homes, patient advocacy organizations, and other stakeholders. Each QIO works to reduce avoidable readmissions by improving processes relating to issues such as medication management, postdischarge follow-up, and care plans for patients who move across health care settings.29

Health Services Advisory Group (HSAG) is multistate QIO tasked by CMS to assist communities, hospitals, and postacute providers with improving the quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries who transition among care settings. HSAG is currently in the preliminary planning phase, recruiting stakeholders to form a Greater Sacramento Collaborative in California. The collaborative is multidisciplinary and customized by its members based on root cause analyses identified using Lean methodology (an approach used to accelerate the velocity and reduce the cost of any process) and brainstorming sessions. Their work continues to evolve with the aim of reducing hospital readmissions and identifying solutions to transfer information efficiently between various settings in their region.

CONCLUSION

TOC is a complex and time consuming endeavor, but it is worthy of implementing at each and every health care setting to improve patient outcomes. While implementation may take time, energy, and effort, the investment will pay dividends as our health care marketplace changes from fee-for-service to an outcomes-based model, and pharmacists and pharmacy technicians may play a larger role going forward.

REFERENCES

- The Joint Commission. Hot Topics in Health Care. Transitions of Care: The need for a more effective approach to continuing patient care. June 27, 2012. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Hot_Topics_Transitions_of_Care.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Report to the Congress: Reforming the Delivery System, Washington, D.C.: MedPAC; June 2008. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/Jun08_EntireReport.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Health care. Improving Transitions of Care: Handoff Communications. http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/assets/4/6/handoff_comm_storyboard.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- Coleman EA, Perry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1882-1888.

- Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Gabrowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2010; 29:57-64.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality Measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/SNF-Quality-Reporting.html

- http://ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/showarticle.aspx?id=54. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Lu Y, Clifford P, Bjorneby A, et al. Quality improvement through implementation of discharge order reconciliation. Am J Health Sys Pharm. 2013;70:815-820.

- Sinavi LD, Beizer J, Akerman J, et al. Medication reconciliation in continuum of care transitions: a moving target. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(9):668-672.

- Kogut SJ, Goldstein E, Charbonneau C, et al. Improving medication management after a hospitalization with pharmacist home visits and electronic personal health records: an observational study. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2014;6:1-6.

- Smith JD, Coleman EA, Min S. A new tool for identifying discrepancies in post- acute medications for community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2014;2(2):141-147.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Project Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (BOOST) Implementation Toolkit. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality_Innovation/Implementation_Toolkits/Project_BOOST/Web/

Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/Boost/Overview.aspx. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- Boston University School of Medicine. Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED). http://www.bu.edu/fammed/projectred/index.html. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Berkowidz RE, Fang Z, Helfand BK, et al. Project ReEngineered Discharge lowers hospital readmissions of patients discharged from a skilled nursing facility. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(10):736-40.

- Institute for Health care Improvement. State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR). http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Completed/STAAR/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- Ouslander, J, Perloe M, Givens J, et al. Reducing potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: results of a pilot quality improvement project (INTERACT). J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;15(3):162-170.

- Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC). 2012 The Patient-Centered Medical Home: Integrating Comprehensive Medication Management to Optimize Patient Outcomes Resource Guide. https://www.pcpcc.org/guide/patient-health-through-medication-management. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Roberts SA, Burton J, Mendoza PL, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-led bedside delivery service for cardiology patients at hospital discharge. Western States Conference. May 2014. http://www.avoidreadmissions.com/wwwroot/userfiles/documents/305/medication-management-community-and-hospital-driven-pharmacy-interventions-roberts-and-barton.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2016,

- Kessels RP. Patient’s memory for medical information. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(5):219-222.

- Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization; a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:520-528.

- Morisky Scale. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.aparx.org/resource/resmgr/Handouts/Morisky_Medicat ion_Adherence.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- ASHP-APhA Medication Management in Care Transitions Best Practices http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Policy/Transitions-of-Care/ASHP-APhA-Report.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Walgreens. Service for business. www.walgreens.com/health care/business/ProductOffering.jsp?id=wellTransitions. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Hubbard, T, McNeill N. Improving Medication Adherence and Reducing Readmissions. October 2012. http://www.nacds.org/pdfs/pr/2012/nehi-readmissions.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2016.

- Freund JE, Martin BA, Kieser MA, et al. Transitions in care: medication reconciliation in the community pharmacy setting after discharge. Inov Pharm. 2013;4:Article 117.

- University of Cincinnati Health News. Pharmacy study expects to lower hospital readmissions. http://healthnews.uc.edu/news/?/24708/. Accessed November 30, 2015

- Sen S, Bowen JF, Ganetsky VS, et al. Pharmacists implementing transitions of care in inpatient, ambulatory and community practice settings. Pharmacy Practice. 2014;12(2):439-447.

- Evans M. Residential therapy-hospitals take on finding housing for the homeless patients, hoping to reduce readmissions, lower costs. Mod Healthc. 2012;42(39):6-7.

- The Joint Commission. Hot Topics in Health Care, Issue 2. Transitions of Care: The need for collaboration across entire care continuum. February 19, 2013. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/TOC_Hot_Topics.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Quach JA, Burton J, Hua S, et al. Reduce medication errors by doing early medication reconciliation in the emergency department. Western States Conference. May 2014.

- Salanitro A, Kripalani S, Resnic, J, et al. Rationale and design of the multicenter medication reconciliation quality improvement study (MARQUIS). BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:230.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Your Discharge Planning Checklist. Revised June 2015. https://www.medicare.gov/Publications/Pubs/pdf/11376.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- Discharged Planning Proposed Rule Focuses on Patient Preferences. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2015-Press-releases-items/2015-10-29.html. Accessed January 25, 2016.

- MARQUIS Implementation Manual. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/MARQUIS/

Download_Manua_Medication_Reconciliation.aspx. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Byrnes J, Fifer J. Recommendations for responding to changes in reimbursement policy. Front Health Serv Manage. 2010;27:3-11.

- Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1997;277(4):307-311.

- National Quality Forum. https://www.qualityforum.org/NPP/docs/Preventing_Medication_Error_CAB.aspx. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Return on Investment Tool. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/PatientSafety/ASHPMedic ationReconciliationToolkit_1/MedicationReconciliationBasics.aspx. Accessed January 25, 2016.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed January 28, 2016.

- Thompson CA. Pharmacy departments innovate to reduce readmissions penalty. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2013;70:296, 298.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accountable Care Organizations. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ACO/index.html?redirect=/ACO/ and http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Shared Savings Program. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html?redirect=/sharedsavingsprogram. Accessed January 25, 2016.

- Value-Based Purchasing Payment Adjustments. Medicare/Hospital Compare. https://www.medicare.gov/HospitalCompare/Data/payment-adjustments.html. Accessed January 25, 2016.

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HCAHPS Executive Insights Spring 2015. http://www.hcahpsonline.org/executive_insight/. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- American College of Physicians. What practices need to know about transition of care management codes. www.acponline.org/running_practice/payment_coding/coding/tcm_codes.htm. Accessed November 30, 2015.

- Vecchione, A. Pharmacy Practice News. MTM Services Effective, But Where’s the Payment? May 14 2008.

- National Transitions of Care Coalition http://www.ntocc.org/. Accessed January 25, 2016.

Back to Top