Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Understanding the Mechanisms of DMARD Therapy and MTM Strategies in Rheumatoid Arthritis

INTRODUCTION

Arthritis is a widespread condition with a prevalence that continues to increase. An analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey found that, from 2013 to 2015, 54.4 million people—equivalent to 22.7% of the adult population in the United States (U.S.)—had doctor-diagnosed arthritis. Of these patients, 43.5% faced activity limitations due to the disease.1 By 2040, an estimated 78.4 million individuals, or roughly one-quarter of the population, will have a diagnosis of arthritis.2 These numbers include various forms of arthritis and, though osteoarthritis is the predominant form, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an important contributor to these growing numbers and the associated activity limitations.

Overall, 1.3 to 1.5 million American adults are estimated to have RA.3,4 RA is a chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disease most commonly involving the joints of the wrists, fingers, and feet. It is accompanied by severe deformity and joint destruction, resulting from inflammation and hypertrophy of the synovial membrane of the diarthrodial joints.5 Symptoms typically develop between the ages of 30 and 50 years, and women are more likely to be diagnosed with RA than men.6 The associated systemic inflammation in RA is linked to several comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), which plays a role in the increased burden of RA.7 Patients with RA have increased mortality and shortened life expectancy compared to the general population owing to the increased frequency of these comorbidities and extra-articular manifestations of disease.8

In the U.S., the annual costs for RA patients, employers, family members, and the government are approximately $39.2 billion: of this, direct costs total approximately $8.4 billion.9 The mean annual costs for patients with RA are 2 to 3 times higher than costs for the general population.10 An analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey revealed that the annual expenditures for all health services per patient with RA totaled $13,012 in 2008 U.S. dollars; for non-RA patients, this total was $4950.11 Pharmacy costs were the greatest medical expenditure, equaling $5825 per year, followed by inpatient costs ($5021) and office visits ($2838).11 Between 1993 and 2011, there were 323,649 hospitalizations for patients with a primary diagnosis of RA.12 Intangible costs related to quality-of-life (QOL) deterioration and premature mortality in RA are estimated to be $10.3 billion and $9.6 billion, respectively.9 RA has a significant negative impact on patients’ abilities to perform daily activities, including work and household tasks.13

Many studies have shown that patients experience considerable work restrictions, decreased productivity, disability, unemployment, or unattainable career choices due to RA.14 Absenteeism costs related to RA in 2015 were estimated to be $252 million.15 Disability within as little as 10 years following diagnosis is a distinct possibility for these patients.15

Considering the debilitating physical damage, increased healthcare costs, decreased QOL, and lost productivity possible with RA, effective treatment is important. There are currently many unmet needs in the RA patient population. Despite advances in the treatment of this inflammatory condition, as well as updated treatment guidelines, many patients are still undertreated, leading to high levels of disease activity and decreased QOL. Adding to this problem is limited access to rheumatologists. By 2025, the demand for rheumatologists is expected to exceed supply by 2576 adult and 33 pediatric rheumatologists.2 As more is understood about the needs of RA patients, pharmacists have opportunities to fill several roles in their care: with better understandings of the medical needs of RA patients and the treatment options that are available, pharmacists can expand their roles in the management of RA and ensure that patients receive high-quality care.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND APPROACH TO TREATMENT OF RA

RA is characterized by swelling of the synovium—the soft tissue lining the spaces of diarthrodial joints—with resulting damage to articular structures.7 The process behind these structural changes and the systemic inflammation is complex, involving the innate and adaptive immune systems. In predisposed patients, the body develops autoantibodies against citrullinated peptides (ACPAs) and rheumatoid factor (RF). This occurs before inflammation and adhesion molecule formation in the synovium. Macrophages and lymphocytes (primarily CD4+ T- cells) move to the affected synovial tissues and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-alpha, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, various interleukins [ILs], interferon gamma).16 The activation and infiltration of T-cells and macrophages leads to production of IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL- 10, and IL-17; TNF-alpha; platelet-derived growth factor; insulin-like growth factor; and transforming growth factor beta.17 The effect is synovial tissue inflammation and proliferation, cartilage and bone destruction, and systemic effects.17 B-cells also infiltrate the synovium and produce pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. This complex combination of immune responses results in symptomatic RA, though ACPAs and RF can be present years prior to the development of inflammation.7,16,17

Though much about the cause of RA remains unknown, the growing understanding about the underlying inflammation in RA has led to new approaches to treatment and redefined goals of therapy. The focus of RA treatment has been shifting away from managing symptoms to an approach that targets underlying inflammation to prevent disease progression.18 Both the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines promote early and aggressive treatment on the basis of mounting evidence that this approach results in better long-term outcomes and greater rates of sustained remission.13,19 The most recent guidelines promote a treat-to-target approach in RA and early use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).13

The treat-to-target approach includes several key features13,18:

- Definition of a treatment target (remission or, at least, low disease activity)

- Assessment of disease activity using composite measures that include joint counts (both total joint count [TJC] and swollen joint count [SJC])

- Instruments to measure disease activity include the Patient Activity Scale (PAS) or PASII; Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID-3); Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI); Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28); erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI)

- Regular adaptation of therapy if the target is not achieved within a specified timeframe

- Accounting for individual patient factors, including risks

- Shared decision-making with the patient

RA TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment plans outlined in both the ACR and EULAR guidelines begin with traditional DMARDs and include options for biologic DMARDs and targeted synthetic DMARDs, the choice of which depends on individualized patient characteristics and achievement of targets.13,19 Monotherapy is recommended initially and changes in therapy or use of combination therapies are recommended if remission or low disease activity is not achieved. EULAR suggests assessment of patients at 3 months for improvement and at 6 months for achievement of treatment target. Neither guideline is prescriptive in the treatment selected after failure of an agent, but each emphasizes individualized care in the absence of strong evidence to support one DMARD over another. ACR recommendations note that newer agents (e.g., tofacitinib) are recommended with less confidence until more long-term safety and efficacy data are available, though this agent is still listed as an option.13 EULAR guidelines also address this newer agent and include agents that are currently investigational, as well.19 Including agents that are anticipated to be approved in the near future may slow the rate at which guidelines become outdated13,19

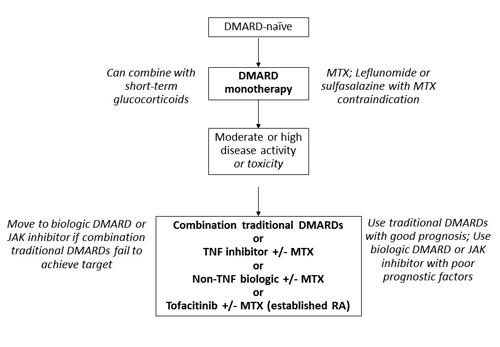

Both the ACR and the EULAR promote the use of a traditional DMARD (e.g., methotrexate [MTX]) with biologic DMARDs on the basis of evidence of improved efficacy.19 Glucocorticoid use is also addressed in the recommendations: only short-term use is indicated in circumstances such as flares or when beginning or changing therapy. Specific dosing for glucocorticoids is not provided, though there is agreement that use should be limited and tapered as soon as possible.13,19 Dosing recommendations, in fact, are not listed for other agents, either. An overview of recommendations for patients initiating therapy for RA and for those who are unable to achieve their treatment target with first-line therapy is presented in Figure 1, which combines recommendations from the ACR and EULAR guidelines.13,19

Figure 1. Adapted Recommendations from the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis13,19

Abbreviations: DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; JAK, Janus kinase; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. |

Unfortunately, adherence to guidelines among practitioners remains low despite evidence to support newer approaches.20 This can lead to postponement of treatment with DMARDs in early disease and delays in treatment escalation when targets are not met.20-22 Pharmacists who are knowledgeable regarding current recommendations can help educate patients on treatment options and facilitate communication with other members of the multidisciplinary care team to improve guideline adherence and attainment of treatment goals.

Early RA therapy: traditional DMARDs and MTX

The ACR and EULAR guidelines share several common principles. For example, both promote early use of DMARDs and indicate that MTX is the preferred DMARD for use in monotherapy.13,19 MTX is an anti-folate drug that inhibits several key enzymes involved in folate, methionine, adenosine, and de novo nucleotide synthesis pathways, which induces anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory effects in patients.23 The recommendation from both the ACR and EULAR guidelines is based on MTX’s efficacy, safety, dosing and administration individualization, cost, and reduction of comorbidities and mortality.13,19 Recommendations for the use of MTX are listed in Figure 2.19,24,25

| Figure 2. Select Recommendations for Methotrexate (MTX) Use in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Other Rheumatic Disorders19,24,25 |

| Start MTX at a dose of 10-15 mg/week; escalate 5 mg every 2 to 4 weeks up to 20-30 mg/week, depending on clinical response and tolerability |

| Parenteral administration should be considered in the case of inadequate clinical response or intolerance |

| Prescription of at least 5 mg folic acid per week with MTX therapy is strongly recommended |

| Patients with early-onset, poor-prognosis RA should be given a 6-month trial of MTX before the decision to add conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or a biologic agent |

| MTX is appropriate for long-term use |

| MTX should not be used for at least 3 months before planned pregnancy for men and women and should not be used during pregnancy or breastfeeding |

In first-line biologic studies, approximately one-third of patients achieved remission on MTX monotherapy.24 However, roughly the same portion of patients did not respond to MTX.24 Dose optimization can be an important factor in achieving results and lack of adequate dosing may explain why many patients do not respond. In a study of RA patients taking MTX as their first DMARD, optimal dose was associated with achieving both remission and normal functioning at 1 and 2 years.24 However, this observational study found that only 26% of patients received optimal MTX dosing.24 A separate study found that MTX is underutilized in RA patients, patients are underdosed, and duration of therapy is insufficient before escalating to other options.25 Overestimation of adverse events with MTX may contribute to these issues.26 Doses of MTX used for oncology indications are much higher than those used for RA, creating an adverse effect profile that is more severe than with lower doses. Due in part to these different uses, MTX is considered a high-alert medication by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices: extra safeguards are needed whenever it is prescribed, dispensed, and administered to avoid toxicity.27

Pharmacists can ensure necessary labs are being performed when MTX is prescribed. Baseline assessment includes aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), albumin, complete blood count (CBC), creatinine, and chest x-ray (obtained within the previous year). Monitoring of ALT with or without AST, creatinine, and CBC should be performed every 4 to 6 weeks until a stable dose is reached, then monitoring can be decreased to every 1 to 3 months.28

MTX pharmacy practice highlights

Pharmacists should take an active role in many steps of the MTX medication use process:

- Educate patients about adverse effects according to MTX dose to avoid overemphasis on adverse effects

- Ensure trimethoprim is avoided with MTX due to a serious interaction26

- Monitor for use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), since these may increase MTX levels27

- Perform screenings for interactions that could increase MTX levels

- Ensure use of folic acid with MTX to decrease adverse events

- Encourage regular blood work and monitoring

- Provide education on injection technique for patients self-administering MTX by the subcutaneous (SC) route

- Review weekly dosing regimen with patients to avoid daily dosing and inadvertent overdose

- Encourage patients to discuss alcohol use with prescriber5,19,26,27

Despite its potential for success, gastrointestinal, hepatic, pulmonary, and hematologic adverse effects may limit MTX use.5 Leflunomide 20 mg/day or sulfasalazine escalated to 3 g/day can achieve similar efficacy to MTX in patients unable to take MTX.19

Inadequate response to monotherapy: treatment options

Guidelines for RA offer several options for patients who are not able to achieve their treatment targets with monotherapy, which is typically MTX (Figure 1). These options include combination of traditional DMARDs, biologic DMARDs (TNF inhibitors and non-TNF biologics) with or without MTX, and targeted synthetic DMARDs (tofacitinib) with or without MTX. EULAR guidelines specify that patients with a poor prognosis should move to a biologic DMARD or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, but the ACR only bases recommendations on disease activity.13,19 Further, the ACR does not rank these choices due to limited comparative evidence and suggests that choices be made on the basis of cost, comorbidities, burden of medication, and side effect profile.13

Traditional DMARD combinations

Many patients who do not achieve their treatment targets may progress to combination therapy with MTX as the anchor drug.28 MTX in combination with sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine was found to be superior to MTX oral monotherapy and no statistically significant difference between this triple therapy and any biologic DMARD plus MTX was shown in a meta-analysis.29 However, the use of combinations of traditional DMARDs is debatable due to the influence of glucocorticoid use in trials, but it is still presented as an option in the guidelines and may be beneficial in some circumstances and according to patient-specific characteristics.30 EULAR guidelines also note a lack of consensus regarding the use of traditional DMARD combinations. The final decision was not to include combinations as an initial treatment suggestion: their use should be at the discretion of the physician and the patient.19

Biologic DMARDs

Guidelines recommend the use of biologic DMARDs in patients who continue to have disease activity or who develop toxicity to other treatments.13,19 The introduction of biologic agents for RA greatly altered the landscape of treatment for this disease and has improved the lives of many patients. Now, several different categories of biologic DMARDs exist, each with a different mechanism of action, and, as previously mentioned, recommendations are not prescriptive when it comes to choosing one agent over another. Comparative studies are lacking, whether comparing agents within a class or among different classes, and the information that is available from indirect comparisons strongly suggests similar efficacy among the classes.31 Therefore, it is important to fully understand the mechanism of action, administration, and safety information for each biologic option so that treatment decisions can be made on the basis of patient-specific factors. Table 1 lists DMARDs used in RA.32-42

| Table 1. Disease-modifying Antirheumatic Drugs Used in Rheumatoid Arthritis32-42 |

| Agent (brand name) |

Target |

Route |

Maintenance dosing |

| Abatacept (Orencia) |

T-cells |

SC, IV |

Every week (SC) Every 4 weeks (IV) |

| Adalimumab (Humira) |

TNF |

SC |

Every other week, or every week in some not receiving MTX |

| Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) |

TNF |

SC |

Every other week or every 4 weeks |

| Etanercept (Enbrel) |

TNF |

SC |

Every week |

| Golimumab (Simponi) |

TNF |

SC, IV |

Every month (SC) Every 8 weeks (IV) |

| Infliximab (Remicade) |

TNF |

IV |

Every 8 weeks or every 4 weeks in some |

| Rituximab (Rituxan) |

B-cells |

IV |

2 infusions 2 weeks apart every 24 weeks (may change interval on the basis of clinical response, but repeat courses should not be given sooner than every 16 weeks) |

| Sarilumab (Kevzara) |

IL-6 |

SC |

Every 2 weeks |

| Tocilizumab (Actemra) |

IL-6 |

SC, IV |

Every week or every other week (SC) Every 4 weeks (IV) |

| Tofacitinib (Xeljanz) |

JAK |

Oral |

Twice daily or once daily (extended-release formulation) |

| Abbreviations: IL, interleukin; IV, intravenous; JAK, Janus kinase; MTX, methotrexate; SC, subcutaneous; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. |

TNF-alpha inhibitors: TNF-alpha inhibitors for RA include adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab. TNF-alpha is a cytokine that is elevated in the synovial fluid and synovium in RA.43 It influences various cells to induce local inflammation and pannus formation, resulting in erosion of cartilage and bone destruction.43 TNF-alpha inhibitors block these effects, which leads to a reduction in chronic inflammation.43

These agents are all considered efficacious and it is recommended that they be used in combination with MTX.31 Differences do exist in the half-lives and, therefore, dosing regimens of the TNF-alpha inhibitors, and these differences influence agent selection.43 Infliximab is a recombinant immunoglobulin G (IgG) 1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) that prevents triggering of the cellular TNF receptor complex. It is administered as an intravenous (IV) infusion at a dose of 3 mg/kg at 0, 2, and 6 weeks and then every 8 weeks. An alternate regimen is 10 mg/kg as often as every 4 weeks.38 Etanercept is a genetically engineered protein that blocks TNF. It is administered weekly as a 50-mg SC injection.35,43 Adalimumab is a mAb that prevents TNF-alpha from binding to its receptors. Dosing is 40 mg SC every other week; it may be dosed as 40 mg once weekly for patients not using MTX.33 Golimumab is a mAb that neutralizes TNF-alpha bioactivity.43 It may be administered as a monthly SC injection or as an IV infusion of 2 mg/kg over 30 minutes at 0 and 4 weeks and then every 8 weeks.36,37 Certolizumab pegol is a recombinant, humanized antibody Fab fragment with affinity for TNF-alpha.34,43 Dosing is 400 mg at weeks 0, 2, and 4, followed by 200 mg every other week. Another dosing option is 400 mg every 4 weeks in the maintenance phase.

TNF-alpha inhibitors are accompanied by warnings and risks for adverse events such as injection site reactions and infections, including reactivation of tuberculosis.26,31 Etanercept may have a lower risk of tuberculosis than mAb TNF- alpha inhibitors because of its unique structure.31,43 There is also concern regarding reactivation or worsening of hepatitis B and hepatitis C.44 The labeling for this class of medications carries a boxed warning that also cites bacterial sepsis, invasive fungal infections (e.g., histoplasmosis), and infection due to other opportunistic pathogens.32-42 Other warnings include lymphoma and other malignancies in children and adolescents.32-42 Heart failure is also listed among the warnings for these agents: clinical studies have raised concern about this risk in patients, but more recent information suggests that risks may not be increased.31 These agents should be used cautiously until conclusive information is available. Evidence is emerging that suggests that TNF-alpha inhibitor use is also associated with the development of demyelinating disease.44 Therefore, extreme caution should also be used for patients at risk of demyelinating disorders.

TNF-alpha inhibitor pharmacy practice highlights: Like with other agents used for RA, TNF-alpha inhibitors offer many opportunities for pharmacists to be involved in the medication use process. Pharmacists should26,45:

- Ensure that necessary testing (e.g., tuberculosis screening) has been performed and appropriate vaccinations have been administered prior to initiation of therapy

- Educate patients on the risk of infection, including receiving recommended vaccinations and avoiding exposure to infections as much as possible

- Inform patients that changes to therapy (e.g., holding immunosuppressive therapy) may be necessary when infection occurs and that they should contact their provider if they contract an infection

- Instruct patients who are self-administering TNF-alpha inhibitors on proper injection technique

- Inform patients that they should avoid use of live vaccines with TNF-alpha inhibitors

Non-TNF biologics: Activated T-cells play a key role in RA pathogenesis.46 Abatacept is a selective T-cell costimulation modulator32: simply, abatacept selectively inhibits T-cell activation by specifically binding to CD80 and CD86 on antigen-presenting cells.45 This binding prevents CD80 and CD86 costimulatory receptors from binding to CD28 on T-cells, thus preventing costimulation during antigen presentation and inhibiting T-cell activation. Dosing is based on body weight and both IV and SC administration is possible. For patients who weigh less than 60 kg, the IV dose is 500 mg; for patients between 60 and 100 kg, the dose is 750 mg; and for patients over 100 kg, a 1000-mg dose should be administered via IV infusion over 30 minutes.32 SC administration is once weekly and can be given with or without an IV loading dose. The loading dose should be based on weight, as previously described, followed by the first 125-mg SC injection given within 1 day of the IV infusion. When changing from IV abatacept to SC administration, the first SC dose should replace the next scheduled IV dose.32 Abatacept is approved as monotherapy or in combination with non-TNF DMARDs.32

Abatacept has proven efficacy in several clinical situations. In MTX-naïve patients, the Abatacept Study to Gauge Remission and Joint Damage Progression in Methotrexate-Naïve Patients with Early Erosive RA (AGREE) showed ACR50 (i.e., a 50% improvement in RA symptoms), ACR70, ACR90, and major clinical response rates that were significantly higher with abatacept plus MTX than with MTX alone; the Assessing Very Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment (AVERT) trial demonstrated a greater ability to induce remission with MTX plus abatacept than with MTX monotherapy.46 Several other trials have shown benefits of abatacept in patients who have failed therapy with MTX or TNF-alpha inhibitors.46

There is an increased risk of infection with abatacept, and the warnings associated with abatacept are similar to those with TNF-alpha inhibitors, particularly those related to tuberculosis and live vaccines.32,46 The most common adverse effects are headache, upper respiratory tract infection, and nausea.46

There is evidence for the involvement of B-cell-mediated immune processes in RA, and B-cells are found in the synovial membranes of RA patients.47 Rituximab is a cytolytic antibody directed to CD20, a B-cell-specific surface molecule.47 Its use results in complete depletion of peripheral B-cells, with a partial effect on the B-cells in the synovium.47 The mechanism of efficacy of rituximab in RA remains, in part, unknown, but it is thought that the effects may be mediated via B-cell antigen presentation ability, B-cell production of cytokines, and B-cell production of autoantibodies such as RF. In fact, it has been shown that rituximab has improved efficacy in seropositive RA patients.48

Rituximab efficacy has been established in clinical trials of patients who are MTX naïve, patients with an incomplete response to MTX, and patients with an incomplete response to TNF-alpha inhibitors.48 For RA, rituximab is given in combination with MTX as 2 IV infusions of 1000 mg each administered 2 weeks apart; this course should be repeated every 24 weeks. The interval may alternatively be based on clinical evaluation, but a repeat course may not be administered sooner than every 16 weeks. Rituximab is administered with corticosteroid premedication. DMARDs other than MTX, such as leflunomide, can be used with rituximab, but combinations with TNF-alpha inhibitors have not shown significantly better outcomes.48

Safety concerns with rituximab include reactivation of hepatitis B and a possible association with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. The risk of malignancies and cardiovascular events does not appear to be increased. The main adverse event is mild-to-moderate infusion-related reactions.49 These reactions are less frequent and less severe than those that occur with rituximab use for hematologic malignancies, possibly because RA patients do not experience the cytokine release syndrome associated with tumor cell lysis in B-cell malignancies.49 Rituximab has been linked to hypogammaglobulinemia, but a resultant increased risk of infection is not well established.48

Rituximab pharmacy practice highlights: When patients are prescribed rituximab, pharmacists should44,48:

- Ensure that screening for hepatitis B has been performed

- Ensure patients have been screened for hypersensitivity to murine proteins, infections, congestive heart failure, pregnancy, and hypogammaglobulinemia prior to initiation of therapy

- Ensure that vaccinations are administered prior to treatment whenever possible

- Advise patients and prescribers to avoid use with TNF-alpha inhibitors, since this therapeutic combination is not recommended

- Recommend pretreatment with methylprednisolone to reduce the risk for acute infusion reactions

Research has found that IL-6 is a regulator of both T-cell migration and activation and also of downstream inflammatory response.47 Inhibition of IL-6 receptor function reduces expression of T-cell activation markers and chemokines. It also induces expression of pro-repair gene sets.47 Tocilizumab is an IL-6 receptor antagonist indicated for treatment of moderate-to-severe RA when 1 or more DMARDs have been unsuccessful.41 Tocilizumab inhibits signaling via both soluble and membrane-bound human IL-6 receptors.44 Sarilumab is approved for adult patients with moderately to severely active RA who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to 1 or more DMARDs. It is a fully human IgG1 mAb that binds soluble and membrane-bound IL-6Rα with high affinity.50 Investigational IL- 6 agents include sirukumab, olokizumab, and clazakizumab.51

Tocilizumab can be administered by IV infusion in combination with DMARDs or as monotherapy starting at 4 mg/kg every 4 weeks then increasing to 8 mg/kg every 4 weeks on the basis of clinical response.41 SC dosing using a prefilled syringe is also an option: the dose is 162 mg; in patients weighing more than 100 kg, it is administered weekly, and, in patients weighing less than 100 kg, it is administered every other week with the option to dose weekly on the basis of clinical response.41

Tocilizumab has been studied in treatment-naïve populations and in patients who have failed previous DMARDs. It has been shown to be non-inferior as monotherapy compared to combination with MTX. Most biologic therapy is recommended to be used with MTX, so tocilizumab may be useful for patients who are unable to tolerate MTX.51

Tocilizumab confers a risk of serious infection, including opportunistic infections and tuberculosis.51 Screening for tuberculosis is recommended prior to initiating therapy. Hepatic transaminases can be elevated with tocilizumab administration but clinical effects are not apparent.44 Neutropenia can also occur with tocilizumab.44,51 Gastrointestinal perforations have been seen in some patients taking tocilizumab, making it necessary to use caution in patients with a history of intestinal ulceration or diverticulitis.44 Tocilizumab is associated with increases in cholesterol levels, both low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels. These increases, however, have not been linked to increased cardiovascular risk, but increased monitoring is appropriate.44,51

Sarilumab has demonstrated efficacy across many RA patient subtypes, including patients who have achieved insufficient responses with treatments ranging from MTX to TNF-alpha inhibitors.50 Notably, in a head-to-head comparison, sarilumab monotherapy demonstrated superiority over adalimumab in MTX-intolerant subjects.50 Sarilumab is dosed as 200 mg once every 2 weeks by SC injection.40 Like tocilizumab, it can be used as monotherapy or in combination with MTX.40 The safety profile is also similar to tocilizumab.50

IL-6 inhibitor pharmacy practice highlights: When patients are prescribed an IL-6 inhibitor, pharmacists should41,44,51:

- Ensure that patients have been screened for tuberculosis, history of intestinal ulceration, and history of diverticulitis

- Ensure monitoring of neutrophils, platelets, lipids, and liver function tests throughout course of therapy

- Advise patients and prescribers that abnormal lab results may prohibit treatment initiation

- Counsel patients to avoid live vaccines

- Assess medication profile for possible cytochrome P450 drug interactions26

Anakinra will not be discussed in detail in this module. It was not included in the most recent ACR guidelines due to infrequent use and lack of new data.13 It inhibits IL-1 and has been shown to have modest effects in RA.47

Targeted synthetic DMARDs: JAK-mediated signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of several autoimmune diseases.52 JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and non-receptor tyrosine-protein kinase bind to type I and II cytokine receptors and transmit extracellular cytokine signals to activate various signal transducers and activators of transcription, resulting in cellular immune response.52 Activated JAK functions include cytokine signaling, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and immune cell activation in autoimmune inflammatory disease.53 Tofacitinib, the first JAK inhibitor, decreases T-cell activation, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and cytokine signaling by inhibiting binding of type I cytokine receptors family and γ-chain cytokines to paired JAK1/JAK3 receptors.53 Other JAK inhibitors in phase III development are baricitinib (JAK1, JAK2), filgotinib (JAK1), and peficitinib (JAK1, JAK3).52

Tofacitinib offers a new oral option for patients with RA. Dosing is either 5 mg twice daily with an immediate-release tablet or an 11-mg extended-release tablet that is given once daily.42 Changes in laboratory parameters share similarities with tocilizumab due to inhibition of IL-6 that follows JAK inhibition. Therefore, liver transaminases and lipids should be monitored for increased levels.52 Other potential changes include initial decreases in lymphocytes, neutrophils, natural killer cells, and platelets.52 Rates of serious infections, such as tuberculosis, are comparable to those for TNF-alpha inhibitors and other biologics.52 The risk of viral infections, particularly herpes zoster, is increased with tofacitinib and appears to be a class effect. The live zoster vaccine is contraindicated with current tofacitinib therapy but it can be given in appropriate patients prior to initiation.52 The recombinant, adjuvanted zoster vaccine that was approved in 2017 is indicated for immunocompetent patients over the age of 50 years. Recommendations for its use in the RA patient population are not yet available but will offer another immunization option for patients. Cytomegalovirus has also been reported with tofacitinib.52 Tofacitinib should be used with caution in patients with malignancy,42 though more long-term data are needed to fully assess the malignancy risk.52 Adverse events that were more common with tofacitinib than with placebo in clinical trials were headache and nausea.53

Tofacitinib pharmacy practice highlights: When patients are prescribed tofacitinib, pharmacists should42,52,53:

- Ensure that patients have been screened for tuberculosis prior to initiation of therapy

- Instruct eligible, appropriate patients to receive the herpes zoster vaccine prior to therapy

- Encourage monitoring for changes in lymphocytes, neutrophils, hemoglobin, liver enzymes, and lipids

- Counsel patients to avoid live vaccines

- Assess medication profile for potential drug interactions

SUBOPTIMAL THERAPY: FORMULATING NEW TREATMENT PLANS

Guidelines agree that a treat-to-target strategy is preferred in RA, yet targets may vary from patient to patient, and treatment recommendations are open to many options in most cases.13,19 Expert consensus on treat-to-target recommendations are generic but do indicate that clinical remission, defined as the absence of signs and symptoms of significant inflammatory disease activity, should be the primary target, though low disease activity is an acceptable target in some patients.18 Remission should follow ACR/EULAR criteria using TJC, SJC, and patient global assessment or the CDAI.54 C-reactive protein (CRP) should be included when feasible in clinical practice.18 Patients should be assessed frequently and treatment should be adjusted every 3 months until the target is reached.18 The overarching treat-to-target principles aim to help providers and patients work together to abrogate inflammation and attain the best outcomes.18 Examples of treat-to-target criteria are listed in Table 2.30

| Table 2. Example Treatment Goals in Rheumatoid Arthritis30 |

| Patient should have no: |

Inflammation

Tender or swollen joints

Radiological progression

Comorbidities

(or lower level comorbidities) |

| Patient should have normal: |

Quality of life

Function

Participation in social activities

Occupational activities

Life expectancy |

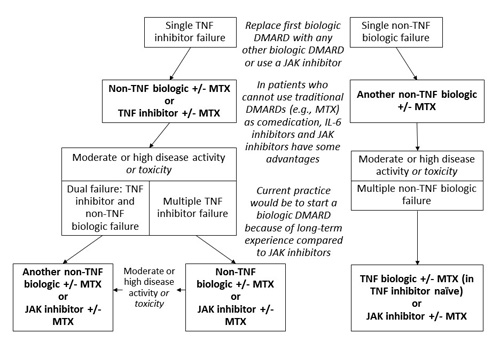

Choosing the most appropriate course of action when patients do not achieve remission is a complicated, though necessary, aspect of RA management. With measures in place to gauge successful response, patients who need treatment modification can be identified. For example, some patients do not respond to initial DMARD therapy (most often with MTX); ACR and EULAR guidelines outline strategies when these same patients do not respond to biologic agents (Figure 3).13,19 The recommendations do not favor any single agent over another or suggest a sequence of use. Additionally, some patients are not responsive to TNF-alpha inhibitors.5 In fact, these agents are ineffective in as many as 30% of patients (defined as failure to achieve an improvement in 20% of ACR criteria).44 More than 50% of patients fail to achieve at least an ACR50 response to agents in this therapeutic category.44 It is debatable whether to opt for another TNF-alpha inhibitor in this situation or to move to a biologic DMARD with a unique mechanism of action. Observational data suggests a non-TNF biologic is most appropriate, though randomized, controlled, head-to-head trials are scarce. Patients who do not initially respond to TNF-alpha inhibitors (i.e., primary non-responders) could benefit from non-TNF biologics because the disease activity may be mediated by cytokines other than TNF.31 Patients who initially do well then lose efficacy with TNF-alpha inhibitors (secondary non-responders) may have developed anti-drug antibodies to their DMARDs. In this case, another agent in the same class may have some success, though lower efficacy is possible. Agents with other targets could also be considered with known or suspected immunogenicity.31 Recommendations do agree that, after 2 TNF-alpha inhibitors have failed, a non-TNF biologic should be used.

Figure 3. Adapted Recommendations from the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism for Biologic Failure in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis13,19

Abbreviations: DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; IL-6, interleukin-6; JAK, Janus kinase; MTX, methotrexate; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. |

Determining when to initiate biologic therapy and selecting the best agent is important in RA management, yet it is not always possible to predict which patients will respond to a particular therapeutic category.55 However, having information about the available treatment choices can help clinicians make educated treatment recommendations. For example, in patients with a history of serious infection, the ACR suggests combination traditional DMARDs or abatacept rather than TNF-alpha inhibitors.31 If a patient has a history of diverticulitis, agents associated with a risk of lower intestinal perforation (e.g., tocilizumab) should be avoided or used with caution.31 Most biologics are used in combination with MTX. In the case of intolerance to MTX, tocilizumab or sarilumab may be a viable option due to proven efficacy as monotherapy.31 Rituximab is the first choice in concomitant multiple sclerosis or past or present lymphoproliferative disorders.31 Such information can help customize treatment to individual patients.

MEDICATION THERAPY MANAGEMENT IN RA: PHARMACIST INTERVENTIONS IN CARE

Treatment of RA can be complex and may require intense clinical monitoring and extensive patient education.45 Additionally, RA is associated with many comorbidities and complications. To help navigate this challenging disease, a multidisciplinary team that includes the pharmacist should be used to help patients achieve goals while avoiding safety pitfalls.56 Medication therapy management (MTM) offers one method for pharmacist participation in RA care. In this setting, pharmacists have central roles in collecting and assessing utilization data, drug information, and adverse event reporting to assess and manage patients with RA.56 MTM approaches have been shown to enhance adherence to injectable medications in RA and may also help reduce adverse events through personalized selection of appropriate medication combinations and dosage regimens.57-59 Patient-reported outcomes can also improve with pharmacist-provided services.57 It is important for pharmacists in a variety of practice settings to understand the components of effective MTM for RA patients and develop standards for communicating necessary information to this population.

Drug therapy education

Pharmacists are skilled in identifying and managing possible contraindications to therapy, drug-drug interactions, adverse event risk and management, and patient education needs for complex medication regimens.45 Basic patient education regarding drug therapy should include dosing, administration, and storage. This information could also be included in comprehensive medication reviews. Because DMARDs vary significantly in method and timing of administration (Table 1), it is important for each patient to understand his or her specific regimen. Many patients may be administering SC biologic DMARDs or MTX: this requires patient education about injection technique, disposal of injection supplies, and storage.45 For drugs that are administered via the IV route, patients should be told what to expect during the infusion including duration, premedication, monitoring of vital signs, and potential infusion-related reactions.45 With oral agents, pharmacists should assess patient adherence and must investigate suspected non-adherence to identify patient barriers to therapy and offer strategies for improvement.31

Expectation of outcomes and adverse events

Patients should know what to expect from RA therapy, including the effect of the agent and the anticipated timeframe for results, which can be weeks to months in some circumstances, as well as possible adverse effects of treatment.45 Adverse drug events are relatively common with DMARDs used in RA. In a study of RA and osteoarthritis patients, it was found that DMARDs were the most common cause of adverse events and that, overall, 44% of events were preventable. It was suggested that education provided by pharmacists could aid in avoiding adverse drug events and improve outcomes.60

Glucocorticoids are also used frequently in RA. Patients should be aware of their adverse effects, which include hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, gastric ulcer, cataract, glaucoma, infections, and dyslipidemia, as well as the need for monitoring for these effects.61 Patients should also understand strategies to mitigate adverse effects when possible.60

Explanation of infection control practices

Patients with RA are at increased risk of developing infections compared with non-RA patients, especially infections involving bone, joints, skin, soft tissues, and the respiratory tract.62 Recommended vaccines for this population include annual influenza, the 13-strain pneumococcal conjugated vaccine followed by the 23-strain pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, and herpes zoster.63 Human papilloma virus, hepatitis B, and yellow fever may also be given on the basis of patient characteristics and needs. Despite the increased requirement for vaccination in these patients, vaccination rates are low. The pneumococcal vaccination rate among RA patients in the U.S. is only 28% and only 46% are optimally vaccinated against influenza.64 Rheumatologists feel they have limited knowledge of the recommendations established by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, creating a need for other clinicians to be involved with this aspect of care.63 Pharmacists can play an essential role in reducing vaccine- preventable diseases in RA patients by verifying immunization histories, educating patients on the need for vaccination, and, in many cases, administering the indicated vaccines. Because many agents used in RA are contraindicated with live vaccines, it is important to assess immunization needs in patients early in therapy—ideally, prior to treatment that would preclude the administration of live vaccines.

Patients should also receive education on other means of combatting infection risk. This includes good hand hygiene and formulating a plan for when infection does occur.45 Some agents for RA should be skipped or delayed when patients are receiving antibiotics.45 Pharmacists are in a position to identify antibiotic use in RA patients and facilitate communication with the healthcare team to ensure safe treatment during infections. It is also important for patients to have a plan for treatment with any anticipated surgical procedures to prevent infection and allow for healing.45

Screening and monitoring for safety and efficacy

Pharmacists can ensure patient safety by reviewing medication profiles for potential drug-drug interactions and also by making patients aware of drugs to avoid. For example, MTX should not be used with trimethoprim. Patients should be instructed to inform all healthcare providers about current treatment and verify safety when antibiotics are needed.26 It is also necessary to be aware of medications that may lead to increased MTX levels and subsequent toxicity (e.g., NSAIDs and PPIs).27

Patients should receive initial screening prior to therapy for many RA agents. For example, prior to TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy, tuberculosis, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C screening should be performed. Pharmacists can confirm that all results are negative before beginning thearpy.45 For MTX, liver function should be assessed and monitored throughout therapy.26 It is necessary to have a baseline ophthalmological examination when beginning hydroxychloroquine and again after 5 years to avoid ocular toxcitity.26 Tocilizumab and sarilumab should begin with lipid assessment, CBC, and liver function tests to establish a baseline so that changes can be noted.45 Prescribing information should be consulted prior to therapy to ensure that all appropriate screening has occurred and that no contraindications to therapy are present. In addition to screening for contraindications, pharmacists should ensure that patients are being evaluated frequently (i.e., every 3 months) for disease activity to assess goals of the treat-to- target strategy.54 Monitoring may also include measurement of antidrug antibodies when efficacy wanes or is not attained.45

Assessment of comorbidities

Screening in RA patients is not limited to contraindications. Many comorbidities exist with RA, including CVD, malignancies, osteoporotic fractures, gastrointestinal disease, depression, and lung disease.65,66 Confusion exists regarding which clinician is responsible for screening RA patients for comorbidities, leading to unacceptably low rates of screening.65,67,68 The risk of and total mortality related to CVD are more than 1.5 times higher in RA patients than in patients without RA, and the CVD mortality rate is similar to the mortality rate of diabetic patients.69-71 The lack of CVD screening leaves many RA patients with undiagnosed hypertension, untreated hyperlipidemia, and undertreatment following a CVD event.65,72 CVD can present earlier in RA patients than in non-RA patients, so screening for comorbidities in RA patients must begin at a younger age.72,73 Pharmacies often offer screening services that could be beneficial for RA patients. Pharmacists can offer these services to patients or refer them to other providers for management of comorbidities. RA patients have also shown increased risk of malignancies and the risk is increased further with some treatment options. Appropriate screening is important for these patients.26

Many patients with RA do not discuss their pain, function, fatigue, and emotional wellbeing with their providers.74 One study reported that 73% of patients felt that they were complaining when they discussed RA symptoms and that roughly half of patients felt too shy to reveal their level of pain.74 As trusted healthcare professionals who are easily accessible to patients, pharmacists have the opportunity to help patients discuss their QOL and facilitate communication with other providers.

CONCLUSION

RA is a life-altering condition that affects substantial numbers of people in the U.S. and worldwide. Many treatment advances have occurred in RA, giving patients a better chance of achieving remission and avoiding or delaying progression of disease, and discoveries related to the pathophysiology of RA have resulted in new therapeutic targets for treatment. This has increased the number of agents available for treating this disease and has diversified the options to allow for increased therapeutic individualization. Unfortunately, many patients are left with unresolved pain and inflammation leading to progressive joint damage, greater risk of comorbidities, and decreased QOL. Multidisciplinary team-based care can help resolve some of the treatment issues that lead to negative outcomes. Pharmacists can play important roles on this team through MTM, patient education, and pharmacy services such as immunization and health screenings. Increased knowledge of treat-to-target strategies and guidelines will help pharmacists ensure that patients are receiving the most appropriate care and will facilitate communication with other healthcare providers. Additionally, familiarity with all treatment classes used in RA, from traditional DMARDs (e.g., MTX) to TNF-alpha inhibitors, non-TNF biologic DMARDs, and target-specific DMARDs (e.g., JAK inhibitors) will help pharmacists guide RA patients through their treatments in the most safe and effective way possible.

REFERENCES

- Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, Brady TJ. Vital signs: prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation - United States, 2013-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(9):246-253.

- Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Barbour KE, et al. Updated projected prevalence of self-reported doctor- diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation among US adults, 2015-2040. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(7):1582-1587.

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al; National Arthritis Data Working Group. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25.

- Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, et al. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955-2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1576-1582.

- Negrei C, Bojinca V, Balanescu A, et al. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: impact and risks of various therapeutic approaches. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11(4):1177-1183.

- Rheumatoid arthritis. American College of Rheumatology website. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am- A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Rheumatoid-Arthritis. Updated March 2017. Accessed October 2017.

- Gibofsky A. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis: a synopsis. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(7 Suppl):S128-S135.

- Gabriel SE, Michaud K. Epidemiological studies in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and comorbidity of the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(3):229.

- Birnbaum H, Pike C, Kaufman R, et al. Societal cost of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(1):77-90.

- Han GM, Han XF. Comorbid conditions are associated with healthcare utilization, medical charges and mortality of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(6):1483-1492.

- Kawatkar AA, Jacobsen SJ, Levy GD, et al. Direct medical expenditure associated with rheumatoid arthritis in a nationally representative sample from the medical expenditure panel survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(11):1649-1656.

- Lim SY, Lu N, Oza A, et al. Trends in gout and rheumatoid arthritis hospitalizations in the United States, 1993-2011. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2345-2347.

- Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1-26.

- Filipovic I, Walker D, Forster F, Curry AS. Quantifying the economic burden of productivity loss in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(6):1083-1090.

- Arthritis by the Numbers: Book of Trusted Facts & Figures. v1.2. Arthritis Foundation website. https://www.arthritis.org/Documents/Sections/About-Arthritis/arthritis-facts-stats-figures.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed October 2017.

- Kontzias A. Rheumatoid arthritis. Merck Manual website. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/musculoskeletal-and-connective-tissue-disorders/joint- disorders/rheumatoid-arthritis-ra. Updated February 2017. Accessed October 2017.

- Wilke W. Rheumatoid arthritis. Cleveland Clinic website. http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/rheumatology/rheumatoid- arthritis/. Published August 2010. Accessed October 2017.

- Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):3-15.

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960-977.

- Markusse IM, Dirven L, Han KH, et al. Evaluating adherence to a treat-to-target protocol in recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: reasons for compliance and hesitation. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(4):446- 453.

- Garneau KL, Iversen MD, Tsao H, Solomon DH. Primary care physicians' perspectives towards managing rheumatoid arthritis: room for improvement. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(6):R189.

- Glauser TA, Ruderman EM, Kummerle D, Kelly S. Current practice patterns and educational needs of rheumatologists who manage patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2014;1(1):31-44.

- Romão VC, Lima A, Bernardes M, et al. Three decades of low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: can we predict toxicity? Immunol Res. 2014;60(2-3):289-310.

- Gaujoux-Viala C, Rincheval N, Dougados M, et al. Optimal methotrexate dose is associated with better clinical outcomes than non-optimal dose in daily practice: results from the ESPOIR early arthritis cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(12):2054-2060.

- Rohr MK, Mikuls TR, Cohen SB, et al. Underuse of methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a national analysis of prescribing practices in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(6):794-800.

- Bornstein C, Craig M, Tin D. Practice guidelines for pharmacists: the pharmacological management of rheumatoid arthritis with traditional and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2014;147(2):97-109.

- Severe harm and death associated with errors and drug interactions involving low-dose methotrexate. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. https://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/showarticle.aspx?id=121. Published October 8, 2015. Accessed October 2017.

- Visser K, Katchamart W, Loza E, et al. Multinational evidence-based recommendations for the use of methotrexate in rheumatic disorders with a focus on rheumatoid arthritis: integrating systematic literature research and expert opinion of a broad international panel of rheumatologists in the 3E Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1086-1093.

- Hazlewood GS, Barnabe C, Tomlinson G, et al. Methotrexate monotherapy and methotrexate combination therapy with traditional and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(8):CD010227.

- Burmester GR, Pope JE. Novel treatment strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2338-2348.

- Rein P, Mueller RB. Treatment with biologicals in rheumatoid arthritis: an overview. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4(2):247-261.

- Orencia [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company;2017.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie, Inc.;2017.

- Cimzia [package insert]. Smyrna, GA: UBC, Inc.;2017.

- Enbrel [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen;2017.

- Simponi [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.;2017.

- Simponi Aria [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.;2017.

- Remicade [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.;2015.

- Rituxan [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Biogen Inc. and Genentech USA, Inc.;2016.

- Kevzara [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.;2017.

- Actemra [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc.;2017.

- Xeljanz [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer;2017.

- Ma X, Xu S. TNF inhibitor therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Biomed Rep. 2013;1(2):177-184.

- Rubbert-Roth A, Finckh A. Treatment options in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing initial TNF inhibitor therapy: a critical review. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11 (Suppl 1):S1.

- Mullican KA, Francart SJ. The role of specialty pharmacy drugs in the management of inflammatory diseases. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(11):821-830.

- Blair HA, Deeks ED. Abatacept: a review in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2017;77(11):1221-1233.

- McInnes IB, Schett G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2328-2337.

- Cohen MD, Keystone E. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2015;2(2):99-111.

- Hainsworth JD. Safety of rituximab in the treatment of B cell malignancies: implications for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5 Suppl 4:S12-S16.

- Raimondo MG, Biggioggero M, Crotti C, et al. Profile of sarilumab and its potential in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:1593-1603.

- Md Yusof MY, Emery P. Targeting interleukin-6 in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2013;73(4):341-356.

- Winthrop KL. The emerging safety profile of JAK inhibitors in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(4):234-243.

- Lundquist LM, Cole SW, Sikes ML. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. World J Orthop. 2014;5(4):504-511.

- Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):404-413.

- Rendas-Baum R, Wallenstein GV, Koncz T, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of sequential biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(1):R25.

- Marion CE, Balfe LM. Potential advantages of interprofessional care in rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(9 Suppl B):S25-S29.

- Stockl KM, Shin JS, Lew HC, et al. Outcomes of a rheumatoid arthritis disease therapy management program focusing on medication adherence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(8):593-604.

- Wong BJ. An approach to preventing methotrexate prescribing errors in rheumatoid arthritis. Hosp Pharm. 1993;28(11):1081-1082.

- van der Goes MC, Jacobs JW, Boers M, et al. Patient and rheumatologist perspectives on glucocorticoids: an exercise to improve the implementation of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations on the management of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1015-1021.

- Tragulpiankit P, Chulavatnatol S, Rerkpattanapipat T, et al. Adverse drug events in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis ambulatory patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15(3):315-321.

- Hoes JN, Jacobs JWG, Boers M, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations on the management of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(12):1560-1567.

- Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, et al. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2287-2293.

- Baker DW, Brown T, Lee JY, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve influenza, pneumococcal, and herpes zoster vaccination among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(6):1030-1037.

- Friedman MA, Winthrop KL. Vaccines and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: practical implications for the rheumatologist. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2017;43(1):1-13.

- Dougados M, Soubrier M, Antunez A, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis and evaluation of their monitoring: results of an international, cross-sectional study (COMORA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):62-68.

- Loza E, Lajas C, Andreu JL, et al. Consensus statement on a framework for the management of comorbidity and extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(3):445-458.

- Vis M, Güler-Yüksel M, Lems WF. Can bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis be prevented? Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(10):2541-2553.

- van Staa TP, Geusens P, Bijlsma JW, et al. Clinical assessment of the long-term risk of fracture in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(10):3104-3112.

- Mackey RH, Kuller LH, Moreland LW. Cardiovascular disease risk in patients with rheumatic diseases. Clin Geriatr Med. 2017;33(1):105-117.

- Desai SS, Myles JD, Kaplan MJ. Suboptimal cardiovascular risk factor identification and management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cohort analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(6):R270.

- Lindhardsen J, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, et al. The risk of myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):929-934.

- Jafri K, Taylor L, Nezamzadeh M, et al. Management of hyperlipidemia among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the primary care setting. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:237.

- Barber CE, Marshall DA, Alvarez N, et al; Quality Indicator International Panel. Development of cardiovascular quality indicators for rheumatoid arthritis: results from an international expert panel using a novel online process. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(9):1548-1555.

- Strand V, Wright GC, Bergman MJ, et al. Patient expectations and perceptions of goal-setting strategies for disease management in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(11):2046-2054.

Back Top