Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Expanding the Treatment Armamentarium for ALS: Implications for Psychiatric & Neurologic Pharmacists

OVERVIEW OF AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a disease of motor neuron degeneration leading to progressive weakness in most muscles of the body. Both upper and lower motor neurons can be affected and contribute to a patient's physical symptoms. Weakness usually starts in one area of the body and spreads to other areas. Eventually, weakness affects the diaphragm, leading to respiratory failure and death, which occurs an average of 3 to 5 years after disease onset.1

Epidemiology

In the United States (U.S.), the lifetime cumulative risk of ALS development is 1 in 400. This translates to 1 to 2 new cases per year of ALS per 100,000 people. The minority of patients, approximately 10%, have familial ALS, which is evenly distributed between males and females. The remaining patients have no family history of the disease, which is termed "sporadic ALS." This form afflicts twice as many men as women.1

Extensive research is underway to identify the cause of ALS, but it is not clearly defined at this time. The ALS Registry Act created a National ALS Registry (available at https://www.cdc.gov/als/Default.html), which is the first comprehensive registry of its kind and is designed to be easily accessible by patients and researchers. For the Registry, patients with ALS are encouraged to take a risk-factor survey, which may reveal common factors that have so far eluded researchers. The National ALS biorepository, which is part of the National ALS Registry, stores biological samples for research into genetic causes of the disease.2

Pathophysiology

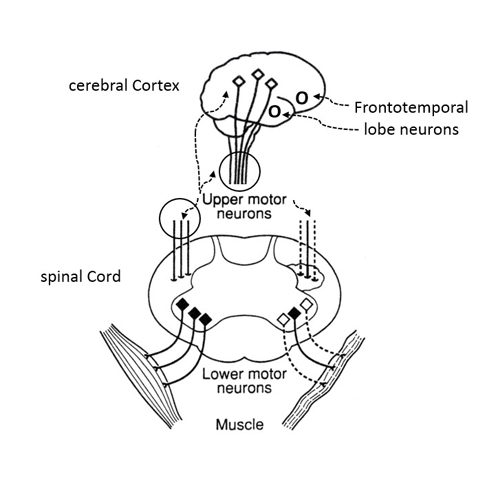

The pathogenesis of ALS has not been entirely elucidated. Familial and sporadic ALS are still viewed as separate entities, but familial ALS research informs hypotheses for sporadic ALS research.1 The common disease process causes upper motor neurons in the motor cortex and lower motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord to die prematurely (Figure 1).3 Upper motor neuron loss leads to muscle spasticity and hyperreflexia. Lower motor neuron loss leads to muscle twitching followed by weakness and atrophy. Loss of neurons in the bulbar region leads to dysarthria, dysphagia, and emotional lability. Frontotemporal lobe dementia, which is seen in some ALS patients, is due to the loss of neurons in these lobes of the brain (Figure 1).3

| Figure 1. Pathology of Motor Neurons in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

|

| Illustration of locations of upper and lower motor neurons and their fibers and frontotemporal neurons. Cerebral cortex: upper motor neurons (open diamonds) and fibers that descend to the spinal cord; frontotemporal lobe neurons (circles). Spinal cord: upper motor neuron fibers descending in the lateral tracts (left side, normal fibers; right side, damaged fibers with "sclerosis" or scar tissue); lower motor neurons (black diamonds) with fibers connecting to muscles (left side, normal fibers; right side, damaged fibers with "atrophic" muscle). Modified from Navigating Life with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.3 |

The cause of neuron loss is unknown, but theories include genetic mutations, excessive neuronal excitatory activity, oxidative damage from free radicals, and environmental factors.1 Genetics research is helping to clarify certain genetic alterations and the related propensities for developing ALS or the phenotypes of ALS (e.g., young age at onset). The current hypothesis is that motor neuron death occurs from a combination of genetic and environmental factors that result in complex cellular processes. In the 5% to 10% of ALS cases that are familial, it is thought that genetics may play a role. However, while several genes have been implicated, no specific genes have yet been identified to explain the illness. Genetic counseling should be recommended if families are interested in genetic testing for ALS.3

Clinical presentation

Average time from symptom onset to diagnosis of ALS is approximately 12 months. This delay may be due to the heterogeneity of presenting symptoms displayed in patients with the disease.1

Common presentations

ALS has varied sites of symptom onset, but weakness typically starts asymmetrically. For example, weakness and atrophy may start in one leg, next move to the arm on the same side, then progress to the opposite leg and arm. Patients may complain of tripping over one foot, often due to lack of coordination attributed to foot drop. Other complaints may include muscle stiffness or spasticity for which patients need to alter their gaits. If symptoms begin primarily with arm and leg involvement, the presentation is termed limb-onset ALS.4

Another common presenting symptom is dysarthria followed by spasticity and dysphagia. Patients may complain of unintentional weight loss or meals taking much longer to finish, difficult-to-understand speech, or outbursts of crying or laughing. This is termed bulbar-onset ALS.4

A few diseases mimic ALS, which makes its diagnosis more complicated. The certainty of the ALS diagnosis can be validated using the El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria. Progression of symptoms over a few months can also help clarify the diagnosis in uncertain cases. Diagnosis is generally made by the use of electromyogram (EMG) and nerve conduction studies.4

Cognitive and behavioral changes

ALS may affect cognition or behavior, and, in some cases, dementia may be the most prominent symptom. Overall, 15% to 20% of patients diagnosed with ALS have frontotemporal lobe dementia.1

Common behaviors seen in these patients include impulsivity, personality changes, limited vocabulary, flat affect, shortened attention span, risky behavior, wandering, getting lost, and excessive eating. Mild cognitive changes may include impaired short-term memory, difficulty with decision-making, and difficulty with multi-step tasks. The ALS Cognitive Behavioral Screen is recommended to assess a patient's cognitive ability and the caregiver's perceptions of cognitive ability.5

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) can be recognized by reports of involuntary emotional outbursts that are out of proportion with the situation. PBA is an important and treatable symptom of ALS that affects up to 50% of patients.6 It is also important to evaluate each patient for signs and symptoms of anxiety or depression. An ALS diagnosis may precipitate a depressed mood and increased anxiety or can trigger an exacerbation for patients with an underlying mood disorder.

TREATMENT APPROACHES FOR ALS

Guidelines for the care of ALS patients have been published by the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the American Academy of Neurology (AAN). A comprehensive set of topics is covered in these guidelines, including respiratory care, nutrition, speech and communication, cognitive and behavioral changes, social support, and pharmacologic therapy.5-7 The only 2 interventions that have shown improved duration of survival are noninvasive ventilation and nutritional support.7 AAN has published quality measures for ALS care.5

Disease-modifying therapy

There are 2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications to slow disease progression in ALS: riluzole and edaravone. Both have distinct characteristics that must be considered when choosing therapy, including route of administration, side effects, and cost.

Riluzole

Riluzole (Rilutek) was approved in 1995. The first trial with this agent demonstrated a median survival (defined as mortality from any cause or tracheostomy) that was 3 months longer with riluzole at 12 and 21 months compared with placebo.8 A Cochrane review of riluzole for ALS published in 2012 reviewed 4 randomized clinical trials and concluded that it likely prolongs median survival by up to 3 months and is not associated with significant safety concerns.9 The exact mechanism of riluzole is unknown but proposed mechanisms include decreased glutamate-induced excitatory neurotransmission and inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels. The starting and target dose of riluzole is a single 50-mg tablet orally (or per feeding tube) twice daily for the remainder of the patient's life. The manufacturer recommends administering riluzole at least 60 minutes prior to meals (or tube feeds) due to reduced absorption and 20% reduced area under the curve.10

The most common side effects of riluzole include nausea, asthenia, and somnolence. Monitoring of liver function tests is recommended particularly during the first year of therapy and caution is advised in patients with a history of liver impairment.10 Riluzole is now available in generic form but the current cash price for patients is approximately $200 per month.11

Edaravone

Edaravone (Radicava) was approved for the treatment of ALS in May 2017 and became commercially available in August 2017. The first placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of edaravone was conducted in a Japanese population and evaluated disease progression as defined by decline in ALS functional rating scale revised (ALSFRS-R) score.There was no significant difference between placebo and active treatment in total ALSFRS-R scores during the 6-month trial duration. It is noteworthy to consider that all patients were permitted to take concomitant riluzole during the study.12

A small subgroup of the patients in this trial showed potential benefit from edaravone compared with placebo, and these results prompted a similar 6-month clinical trial involving only patients who met the following criteria: a diagnosis of definite or probable ALS based on El Escorial revised criteria, a score of 2 or higher in each category of the ALSFRS-R, forced vital capacity of at least 80%, and disease duration less than 2 years.13 Edaravone 60 mg was administered by intravenous (IV) infusion once daily for 14 days and then followed by 14 days without medication: this was deemed cycle 1. During the 5 remaining 4-week cycles, patients received edaravone 60 mg IV once daily for 10 of 14 days and then had 14 days without the infusion. The least squares mean difference in ASLFRS-R score demonstrated 33% less decline in the edaravone group than in the placebo group, which translated to 2.5 points on the 40-point rating scale. The study was published in 2017 and led to FDA approval of edaravone. The exact mechanism of action of edaravone in ALS is not known, but theories include free radical scavenging leading to reduced motor neuron death.12 The most common side effects in the edaravone group were gait abnormality, contusion, and headache.14

Edaravone is only available in 30 mg per 100 mL pre-mixed infusion bags. Therefore, each dose is 2 infusion bags administered consecutively for 6 or more 4-week cycles, based on payor criteria. The manufacturer recommends using caution in patients with reported sulfite allergy since the infusion contains sodium bisulfite.14 Copay assistance is available through the manufacturer of edaravone and information on financial support can be found at www.radicava.com.15 Edaravone administration requires potentially considerable time for daily infusions, IV access maintenance, and travel for infusions. Therefore, the true effect on a patient's quality of life and caregiver burden is still to be determined.

Symptomatic medication therapy

Symptomatic therapy includes medications used to improve patient comfort or quality of life. Well- designed prospective trials are rare and most therapy is based on clinician experience. The most commonly described symptoms of ALS requiring management include sialorrhea, PBA, spasticity, and muscle cramps. In 2017, Ng and colleagues published a Cochrane Review of symptomatic therapies for motor neuron diseases including ALS.16

Sialorrhea and dry mouth

Sialorrhea, or the excess production of saliva, can be very distressing to the patient with ALS. It is believed to be caused by a decreased ability to swallow and control secretions. Medications with mucolytics, a β-receptor antagonist, nebulized saline, or an anticholinergic bronchodilator are widely used to control sialorrhea; however, no controlled studies exist in ALS. Low-dose amitriptyline (25-50 mg daily) is commonly used off-label due to its side effect of dry mouth. Additionally, off-label use of atropine eye drops administered sublingually provides short-term local relief of excess saliva. This can be particularly helpful when the drops are administered before meals or occasions known to exacerbate excess saliva production. Oral glycopyrrolate can also prove beneficial for patients who should avoid amitriptyline due to orthostatic hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, or excessive sedation. Scopolamine patches have been studied the most extensively in ALS-related sialorrhea, but they are not commonly used, according to patient reports. Botulinum toxin A or B injected into the salivary glands is used when other methods fail. There are several prospective trials supporting its use and results may last for weeks to months. Radiotherapy and surgery on the salivary glands are other options.17

While excess saliva is a common problem, dry mouth can also occur in ALS due to decreased fluid intake and anticholinergic medication side effects. Pharmacists can recommend over the counter swabs, glycerin sticks and oral rinses, gels, and sprays to alleviate dry mouth. These products are especially important and helpful for caregivers once patients are bedridden, since sialorrhea and dry mouth become particularly challenging scenarios at that late disease stage.18

PBA

PBA varies in severity but may significantly affect the patient and his or her family due to unpredictable emotional outbursts that are characterized by uncontrollable episodes of crying and/or laughing. Dextromethorphan/quinidine (Nuedexta) is the only FDA-approved therapy for PBA. Dextromethorphan is a sigma receptor agonist and an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, which may explain its effectiveness in PBA.19 Low-dose quinidine inhibits cytochrome P450 2D6 metabolism of dextromethorphan, thus increasing plasma levels. In a 12-week randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trial, investigators compared dextromethorphan 30 mg/quinidine 10 mg with dextromethorphan 20 mg/quinidine 10 mg and placebo in patients with PBA and either ALS or multiple sclerosis.19 Episodes of PBA were significantly lower for patients taking either dose of dextromethorphan/quinidine than for patients taking placebo. Adverse effects that occurred more frequently in the active treatment groups were dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, and urinary tract infection. Of note, only mild QTc prolongation occurred in the higher-dose group, with a mean change from baseline of 4.8 milliseconds; no patient had a QTc interval longer than 480 milliseconds. Dextromethorphan/quinidine can be compounded in liquid form for easier administration through a feeding tube.20

Interestingly, the Nuedexta Treatment Trial, which was published in 2017, suggested that dextromethorphan/quinidine may improve bulbar function (i.e., speech, swallowing, salivation) in ALS patients, as well.21 However, these results remain to be confirmed by another trial. Other treatment options for PBA, which are less expensive, include low-dose amitriptyline (12.5 -50 mg daily) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.5

Muscle spasticity, pain, and cramps

Spasticity affects ALS patients with upper motor neuron involvement. Spasticity can impair gait, contribute to falls, and may also contribute to muscle pain. Baclofen is the most commonly used agent to combat spasticity, but there are no clinical trials evaluating its use in ALS.16

Muscle cramps can affect patients with ALS by interrupting sleep or contributing to pain. There are several randomized controlled trials investigating treatment for cramps but definitive benefit has not been demonstrated.22 Quinine has historically been prescribed for muscle cramps in ALS, but the FDA strongly discourages its use due to cases of severe blood dyscrasias, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.23 On the basis of positive results from a small trial, mexiletine may be prescribed for muscle cramps.24

Urinary control

Urinary frequency or incontinence may occur in some ALS patients and can be complicated by lack of mobility. No particular agent is preferred to manage this symptom and no trials are available to support the use of any agent over another. However, oxybutynin is typically used as first-line therapy due to its low cost.1

Mental health

Patients and families should be assessed for their mental health needs. ALS takes a toll on patients, their caregivers, and their families. Depression and anxiety may occur and, while little research has occurred specific to this population, treatments used for depression and anxiety may be helpful to ease the burden.4

THE PHARMACIST'S ROLE IN ALS

Pharmacists are accessible and able to help patients optimize care in ALS. Education and medication therapy management represent key areas in which pharmacists can assist patients.

Recognition of early symptoms

Pharmacists are easily accessible healthcare professionals. They are well-positioned to make timely recognitions of ALS symptoms such as rapid onset dysarthria, unintentional weight loss, unilateral hand weakness, or foot drop, which can improve time to proper diagnosis and early therapy. If ALS is suspected, referral to a neurologist is key to undergo an EMG and nerve conduction studies. These tests provide the neurologist with information in order to rule out other diseases that may present similarly to ALS.4

Multidisciplinary care and optimization of medication therapy

Pharmacists, as part of the healthcare team, should review ALS patients' medication lists to ensure effective and safe medication therapy.25 Pharmacists can also support ALS quality measures such as discussing disease-modifying pharmacotherapy, offering treatment options for ALS symptoms including PBA and sialorrhea, and discussing falls that have occurred. Also, specialist pharmacists with additional training or Board Certification in Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacy work in many treatment settings and can provide additional expertise or participate with multidisciplinary teams. This group of experts may be particularly helpful in recommending and monitoring psychiatric medications as part of the neurological care team. Table 1 lists other areas in which pharmacists can play a role to improve the care of ALS patients.25

| Table 1. Areas of Focus for Pharmacotherapy in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)25 |

- Effectiveness of each medication

- Undesirable side effects (e.g., constipation, orthostatic hypotension)

- Cost considerations and affordable alternatives

- Assistance with copays or patient assistance programs

- Helping to direct families to clinical trial programs and discussing the details of investigational treatments with patients and families

- Drug interactions (e.g., QTc prolongation, additive anticholinergic effects)

- Medication suitability and compounded alternatives for administration via feeding tube

- Elimination of medications not viewed as effective, especially as dysphagia worsens

- Immunization history to ensure receipt of influenza vaccine and pneumonia vaccines

- Frequency and severity of muscle cramps

- Education to reduce fall risk associated with medications (e.g., amitriptyline) in the context of very limited mobility

- Adjustment of antihypertensive and glucose-lowering medications with disease progression

- Safe use of alternative or nutraceutical medications (e.g., consider maximum daily dose, interactions with anticoagulants)

- Encouraging patients and families to seek help for psychiatric and mental health needs

- Linking families to local and national ALS organizations

|

Communication

One of the most troubling features of ALS, particularly for patients with bulbar-onset disease, is the loss of verbal communication. Resources for alternative communication abound and are not necessarily expensive. Options include a white board with marker, alphabet card/board, phone or tablet apps, and eye gaze-directed communication devices.6 Pharmacists can also help direct families and patients to local ALS associations that may have loan equipment for patients with a variety of needs.

Patient education

The internet provides endless "cures" and "treatments" to reverse or cure ALS, and patients diagnosed with a fatal disease may be particularly susceptible to scams and risky treatments. However, resources such as those found in Table 2 are available to provide evidence-based evaluations of such therapies.26-29

| Table 2. Helpful Resources for Evaluating Treatments for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) |

| Patientslikeme.com26 |

Crowd-sourced information on a variety of diseases; patients can report their therapies, side effects, and perceived efficacies and compare them with other patient reports |

| ALSuntangled.com27 |

Clinician-authored monographs of alternative and off-label therapies for ALS |

| Clinicaltrials.gov28 |

Comprehensive list of clinical trials that is searchable by disease state, drug name, and other identifiers; patients interested in trial therapy can use contact information to locate trial investigators and determine eligibility |

| ALSA.org29 |

Official website of the ALS Association; provides consistently updated information for ALS patients and their caregivers about everything related to ALS; information and links are provided to the National ALS Registry |

CONCLUSION

ALS is a fatal disease, but compassionate, individualized, effective symptomatic therapy can improve each patient's quality of life. Pharmacists educated about the goals of ALS therapy and available patient resources can provide important guidance for patients and their families. Current research for new therapies may present future opportunities for pharmacist involvement.

REFERENCES

- Brown RH, Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(2):162-72.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Registry. https://www.cdc.gov/als/Default.html. Updated February 8, 2018. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Bromberg MB, Bromberg DB. Navigating Life with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. New York, NY: American Academy of Neurology/Oxford University Press;2017:2.

- EFNS Task Force on Diagnosis and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; Andersen PM, Abrahams S, Borasio GD, et al. EFNS guidelines on the clinical management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MALS)--revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(3):360-75.

- Miller RG. Quality improvement in neurology: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis quality measures: report of the quality measurement and reporting subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(24):2136-40.

- Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2009;73(15):1227-33.

- Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2009;73(15):1218-26.

- Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):585-91.

- Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Moore DH. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD001447.

- Rilutek [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC;2008.

- Riluzole: generic rilutek. https://www.goodrx.com/riluzole?drug-name=riluzole. Updated 2018.

- Abe K, Itoyama Y, Sobue G, et al; Edaravone ALS Study Group. Confirmatory double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety of edaravone (MCI-186) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15(7-8):610-7.

- Writing Group; Edaravone (MCI-186) ALS 19 Study Group. Safety and efficacy of edaravone in well defined patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(7):505-12.

- Radicava [package insert]. Jersey City, NJ: Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America, Inc.;2017.

- Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America, Inc. Product Access Program: Searchlight Support. https://www.radicava.com/patient/support/searchlight-support/. Updated 2018. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- Ng L, Khan F, Young CA, Galea M. Symptomatic treatments for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:CD011776.

- Banfi P, Ticozzi N, Lax A, et al. A review of options for treating sialorrhea in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Respir Care. 2015;60(3):446-54.

- Kaminski KH. Oral care for people living with ALS. http://www.alsa.org/als-care/resources/publications-videos/factsheets/fyi-oral-care.html. Updated September 2014. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Pioro E, Brooks B, Cummings J, et al; Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy Results Trial of AVP-923 in PBA Investigators. Dextromethorphan plus ultra low-dose quinidine reduces pseudobulbar affect. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(5):693-702.

- Wahler RG Jr, Reiman AT, Schrader JV. Use of compounded dextromethorphan-quinidine suspension for pseudobulbar affect in hospice patients. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(3):294-7.

- Smith R, Pioro E, Myers K, et al. Enhanced bulbar function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the Nuedexta Treatment Trial. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):762-72.

- Baldinger R, Katzberg HD, Weber M. Treatment for cramps in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD004157.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: New risk management plan and patient Medication Guide for Qualaquin (quinine sulfate). https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm218202.htm. Published July 8, 2010. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Weiss M, Macklin E, Simmons Z, et al; Mexiletine ALS Study Group. A randomized trial of mexiletine in ALS: safety and effects on muscle cramps and progression. Neurology. 2016;86(16):1474-81.

- Jefferies KA, Bromberg MB. The role of a clinical pharmacist in a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinic. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13(2):233-6.

- Patients Like Me. https://www.patientslikeme.com. Updated 2018. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- ALS Untangled. http://www.alsuntangled.com. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- ALS Association. http://www.alsa.org. Updated 2018. Accessed May 21, 2018.