Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Overcoming Barriers to Optimal Diagnosis and Treatment of Invasive Fungal Infections: Practical Guidance for the Hospital-Based Healthcare Provider

The Evolving Epidemiology of Invasive Fungal Infections and Impact on Patient Risk

Dr. Patterson: Hello, this is Dr. Thomas Patterson from University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. Welcome to this educational activity focused on the management of invasive fungal infections in the hospital setting.

Joining me in this discussion today is Dr. James Lewis II from the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, Oregon.

Our program today addresses overcoming barriers to optimal diagnosis and treatment of invasive fungal infections. We hope to provide practical guidance for you as hospital-based healthcare providers in managing patients at risk for or who have these diseases.

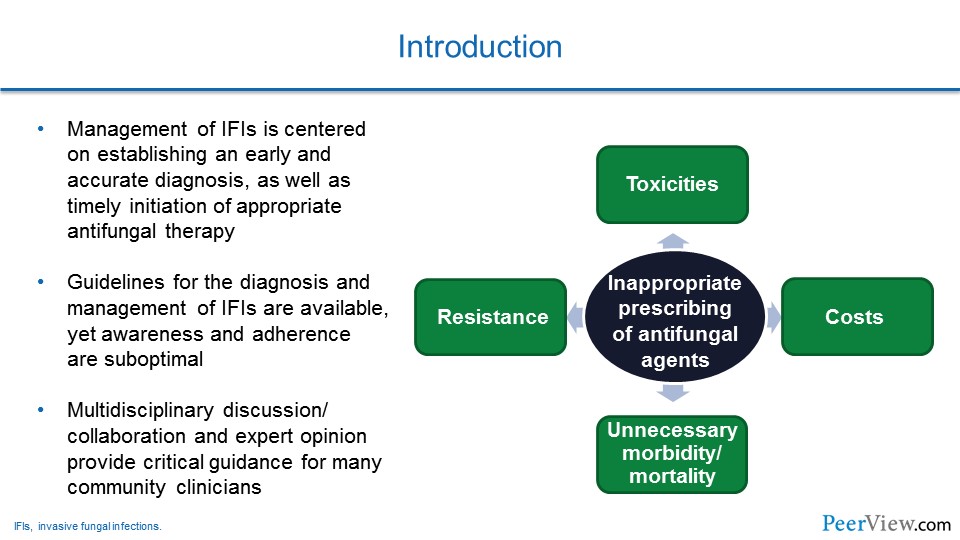

Dr. Patterson: It is important to recognize that the management of invasive fungal infections is centered on establishing an early and reliable diagnosis. An early diagnosis is really key to allowing timely initiation of antifungal agents. But, unfortunately, early diagnostics are still somewhat limited. A number of challenges exist, such as access to those tools or even the availability of rapid tests to establish an effective early diagnosis.

Slide 1

But it is important to recognize that early recognition of infection allows for very prompt antifungal susceptibility testing, as well as if an organism is identified. But, also the prompt initiation of antifungal therapy.

Unfortunately, due to diagnostic uncertainty, in many settings inappropriate use of antifungal agents occurs. That inappropriate use of antifungal therapy can result in excess toxicities, antifungal resistance of the organisms, but also dramatically increased cost. But, unfortunately, if antifungal therapies are not given to patients who need them and are at risk, you can have increased morbidity and mortality that occur by delayed therapy.

Fortunately, there have been a number of guidelines recently published that address management of invasive fungal infections, particularly for more common infections like invasive aspergillosis and other Aspergillus syndromes and candidiasis.

Unfortunately, in many settings it has been documented that clinicians are not aware of some of these recommendations or, even if they are aware, that the adherence to the recommendations is suboptimal.

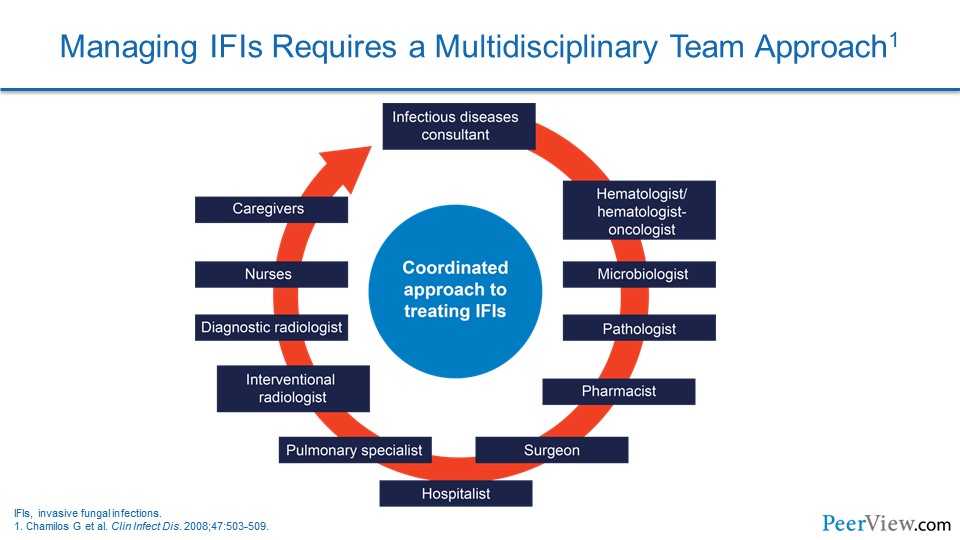

It is also really important for managing these types of infections, we think, to include multidisciplinary discussions and collaborations, as expert opinions will certainly provide guidance and assistance in your management of these patients.

Slide 2

Narrator: Dr. Patterson began the discussion by asking Dr. Lewis about which fungal pathogens he encounters most frequently and the corresponding patient populations at risk for infection.

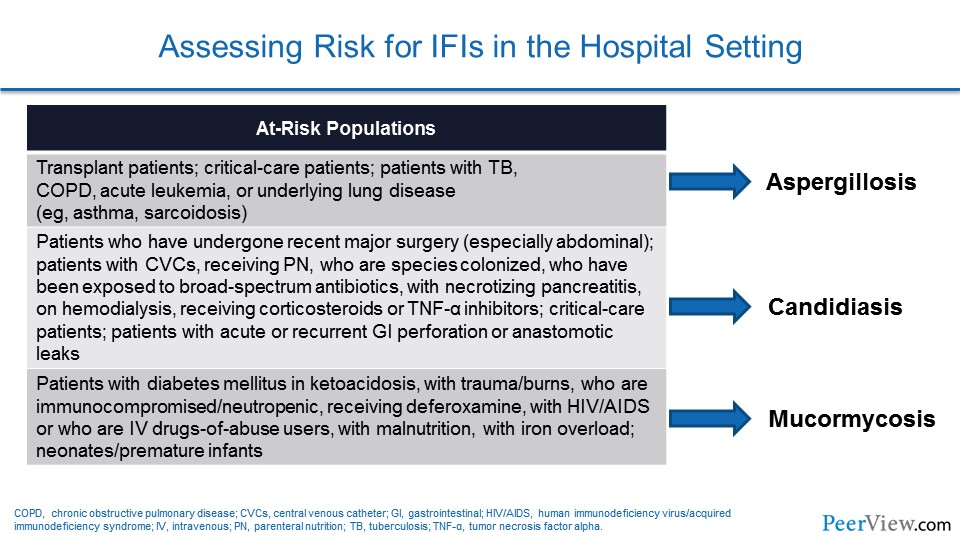

Dr. Lewis: Yeah, Tom. You know, we have really kind of a significant split as far as the epidemiology goes for the patients who we see with invasive fungal infections here, and it is really broken out by their underlying pathologies.

On the one hand, you have our bone marrow transplant program, which is an extremely active program, a large number of stem cell transplants done annually. And, in that group, it is really the Aspergillus that keeps us up at night. And, you know, we do a lot of prophylaxis around preventing that infection with that organism, but that is the organism that we really fear in that population.

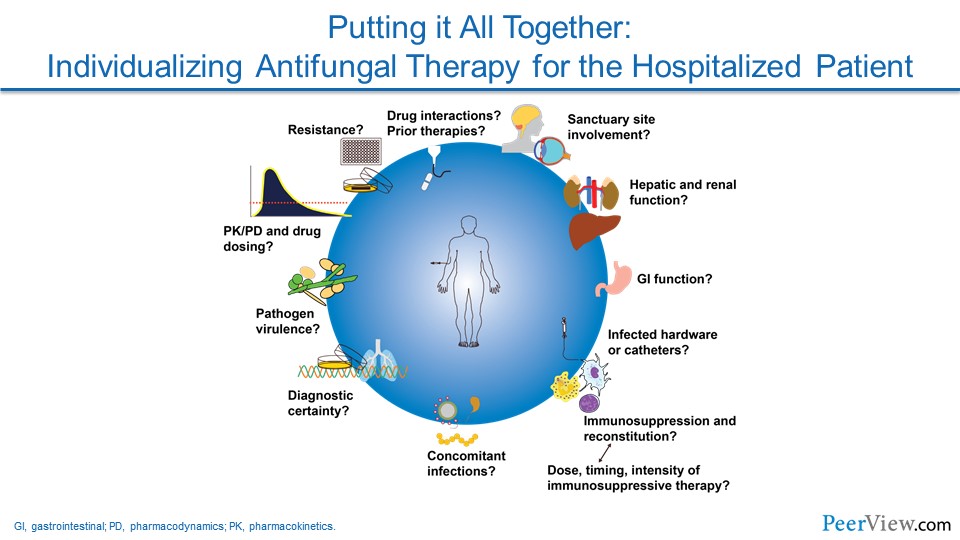

When you shift over to more of our general medical/ general surgical group and especially in our intra-abdominal process patients or our patients who come in and have complicated intra-abdominal surgeries that group, in particular, really Candida is the group or is the organism that causes us the greatest deal of concern there. And so, you know, I think really from an epidemiologic and from a drug selection standpoint, the first thing that we do is really kind of look at the host and really look at what some of the underlying complications associated with that host are, and that really leads us in the direction of which organism it is that we are primarily concerned with. And that really then in turn drives our antifungal selection.

Dr. Patterson: Yes, Jim. I would agree with you. Here in San Antonio, where we see a large trauma population and a lot of intra-abdominal surgical procedures, we have a number of patients presenting at risk for Candida infection. So we see a lot of Candida disease still. But in our more immunosuppressed population, in our leukemics, and in those receiving other forms of chemotherapy, molds like Aspergillus remain very important. I will also add, a little different probably from your setting, here in San Antonio, we also have a number of patients with Mucor, with our diabetic population but also in the trauma patient population as well.

Slide 3

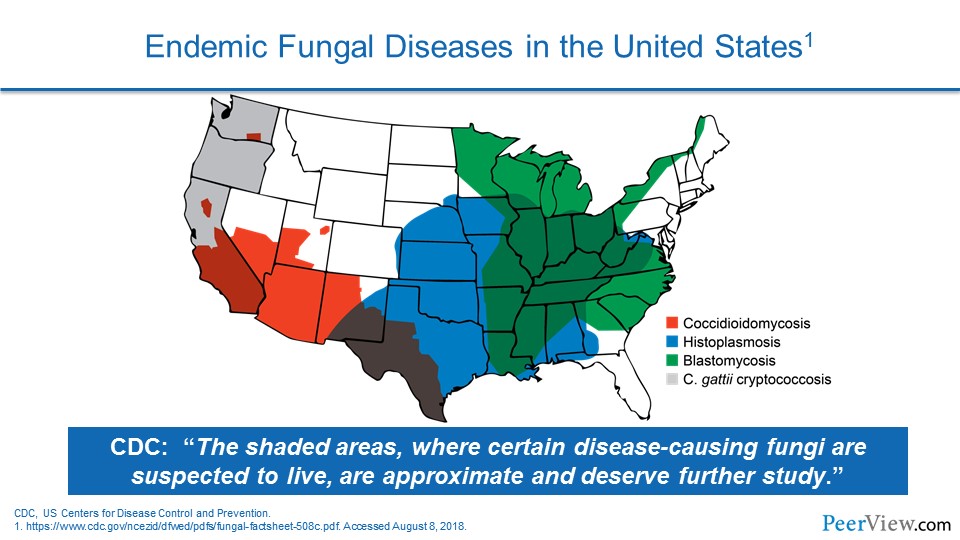

Dr. Patterson: And we also see a number of patients, of course, at risk for endemic fungi like coccidioidomycosis and histoplasma infections, which remain significant in our patient population as well.

Dr. Lewis: And, you know, it is interesting you bring that up, Tom, because one of the bugs I cannot believe I forgot up here in the Pacific Northwest for us is one of those endemic mycoses, and that is Cryptococcus gattii. And as a matter of fact, we are dealing with two patients with that on our inpatient service right now.

You know, so I think one of the things for our audience to always remember is that you hear a lot about Candida and Aspergillus, but depending on where you are geographically, those endemic mycoses can be a real significant challenge for you as well.

Dr. Patterson: Yes, I would certainly agree. I think that the epidemiology has changed in recent years, and, you know, that is attributed to a number of factors. For us, probably not so much the climate sort of issues here, but certainly you have seen that in the Pacific Northwest with C. gattii emerging. The cause, I guess, is not completely clear, but it has certainly changed.

Slide 4

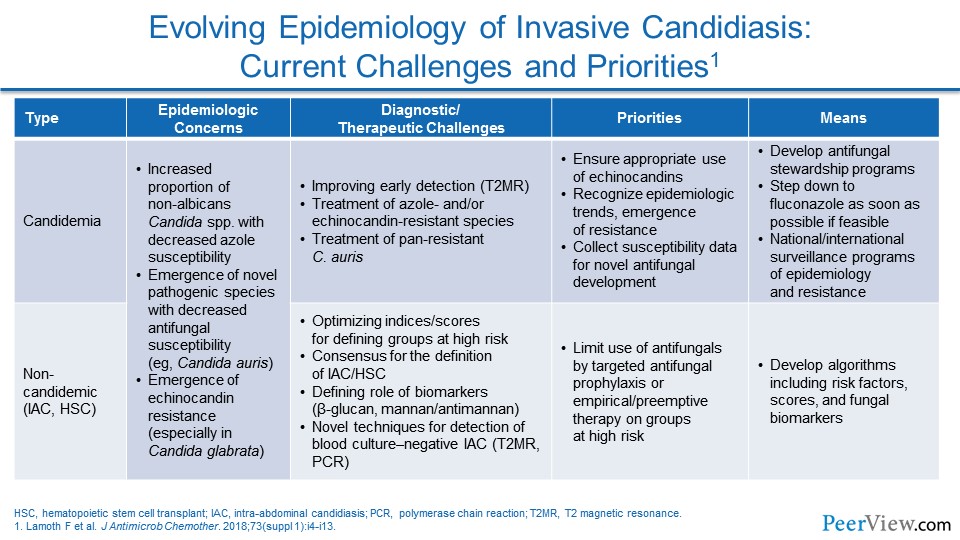

Dr. Patterson: I think we do see change in epidemiology, not only in terms of organisms. If you looked at organisms even for Candida, we see certainly more and more Candida glabrata infections, relative to the number of Candida albicans infections, although those, of course, remain significant as well. But we certainly see more of the unusual molds, black molds, and Mucor along with the Aspergillus infections.

And I think the patient population has changed significantly. Now we see patients receiving biologic agents and more use of steroids, and I mentioned trauma as a significant risk factor as well, and probably the increased use and availability of very extensive intensive care unit care in really sick patient populations, where the risk of fungal disease rises really dramatically.

Dr. Lewis: And you know, it seems too like that the C. glabrata shift is not an isolated event. To me, one of the things that has been most striking in the epidemiology over the last decade or so is to see that emergence of C. glabrata occur and to see that, you know, nationally now, I think last time I looked, it was 30% to 40% of bloodstream isolates in US hospitals are now made up by C. glabrata.

Slide 5

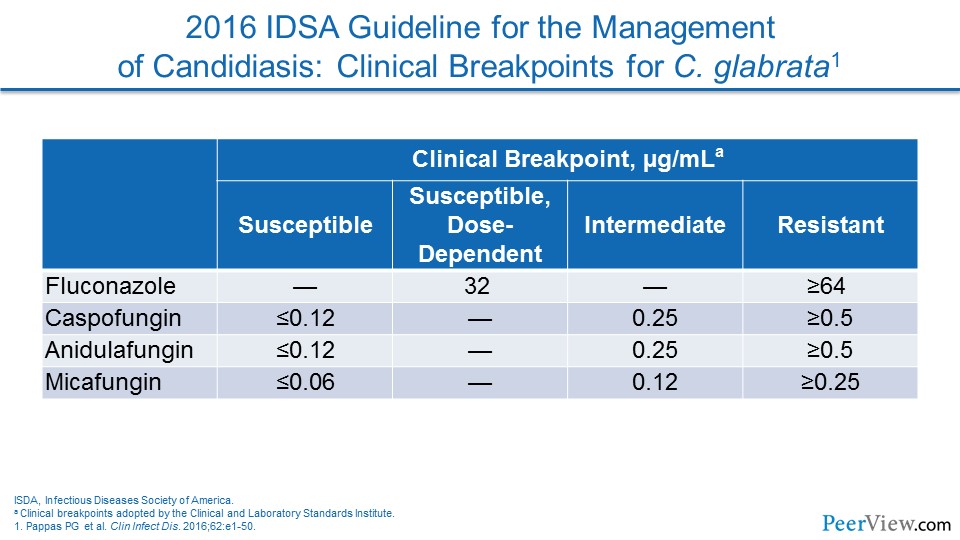

Dr. Lewis: And to me, one of the things from an epidemiologic standpoint that becomes really important at that point is to recognize that the azole susceptibility challenges that come with C. glabrata—and as you talked about very nicely in the intro—with the new 2016 Candida guidelines placing much more emphasis on susceptibility testing than I think a lot of clinicians are used to seeing previously.

Dr. Patterson: Sure. I think the issue of resistance has become a really important issue across the board in invasive fungal disease. Certainly with Candida, we've seen it with C. glabrata, and nationally, we have seen even the emergence of Candida auris that can be multidrug resistant.

Slide 6

Dr. Patterson: So it is important for our listeners I think, to recognize the possibility of these even multidrug-resistant pathogens, C. glabrata being the more common of the Candida species, but C. auris in local settings is really an important pathogen that is really difficult to manage.

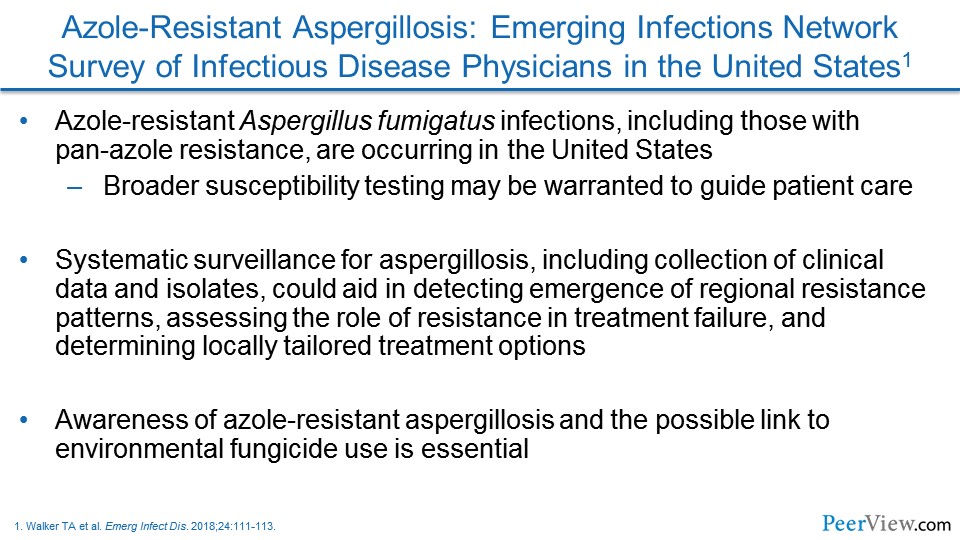

Certainly, in the United States, we have seen less Aspergillus resistance to the azoles, but here at the fungus testing laboratory, Nathan Wiederhold and colleagues here have reported those isolates. And now the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also reported a number of strains in the United States of Aspergillus that are triazole resistant as well.

Slide 7

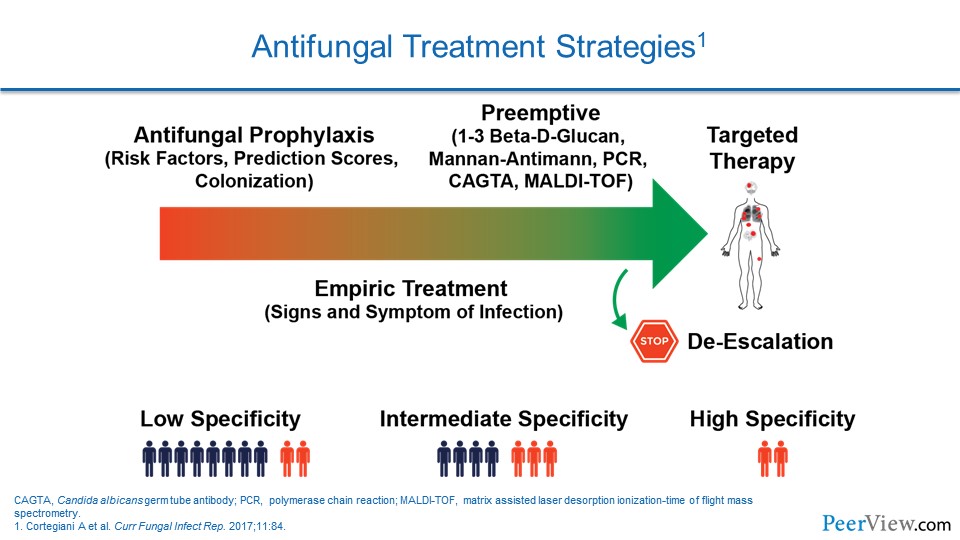

Dr. Patterson: If we turn to which patients might be selected to receive preemptive treatment for invasive fungal infections, can you comment on those aspects of treatment of invasive fungal infection?

Dr. Lewis: I think that you have high-risk groups that are more predisposed or more at risk for developing invasive fungal infections. And I think that, as you alluded to, we have classically thought about it with the leukemics, with the bone marrow transplants, et cetera. But I think that the advent of more and more of these biologics, as well as more and more widespread chronic steroid use, there are a couple of things that you need to think about.

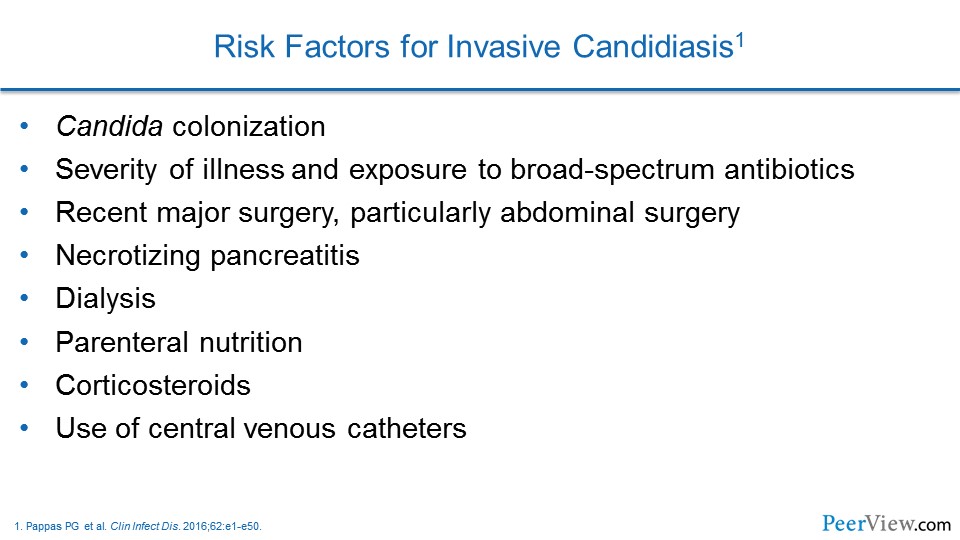

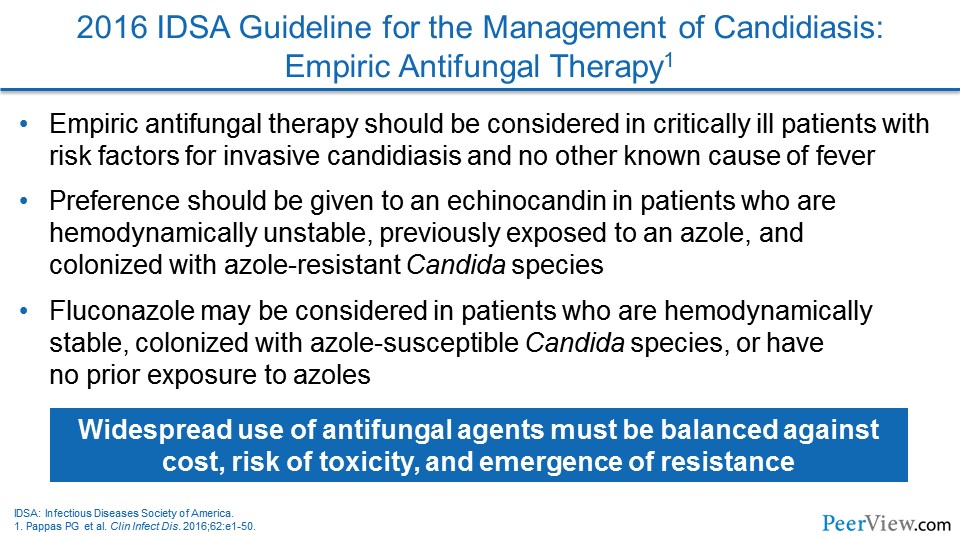

And so I think that when you are considering who you should be screening—I think that those factors really have to come into play. And then, I think when you shift over away from the molds and you move more over toward Candida, the risk factors are very nicely laid out in the 2016 Candida guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

And the problem that I think that a lot of clinicians run into and a lot of us in the hospital run into is it that list of risk factors looks at just about like everybody in every one of your intensive care units. You know, whether it is the broad-spectrum antibiotics or whether it is the central lines, the risk factors that seem to be associated with the development of invasive candidiasis are so prevalent in US healthcare today.

But I think one of the things that is really buried in those guidelines, and something that clinicians need to think, I think, a little bit about sooner, is—and go looking for these patients or going looking for Candida a little bit harder in these patients—are some of these intra-abdominal disasters, for lack of a better term.

You know, the guidelines talk about some of the chronic pancreatitis patients, some of the repeated intra-abdominal perforations, or the intra-abdominal processes that have anastomotic leaks. And those are the folks in whom I think that you need to really be quick to pull the trigger with regards to your screening, whether it is culturing or whether you are fortunate enough to have some of the newer diagnostic technologies that are available.

Dr. Patterson: Yes, I would really agree with you on those comments. I think for Candida particularly, it is really important to recognize the patients at risk. As you pointed out, it is unfortunately a whole lot of the patients in the hospital. I think a message that we both would like to get out and say is we are not advocating antifungal therapy for everyone, but I think, as clinicians, it is really important for you to assess risk in an individual patient.

If a patient is multiply colonized with Candida, there are no other clear sources of infection, they have an abdominal catastrophe, as you commented, and multiple central lines, those patients are at really high risk for infections.

Slide 8

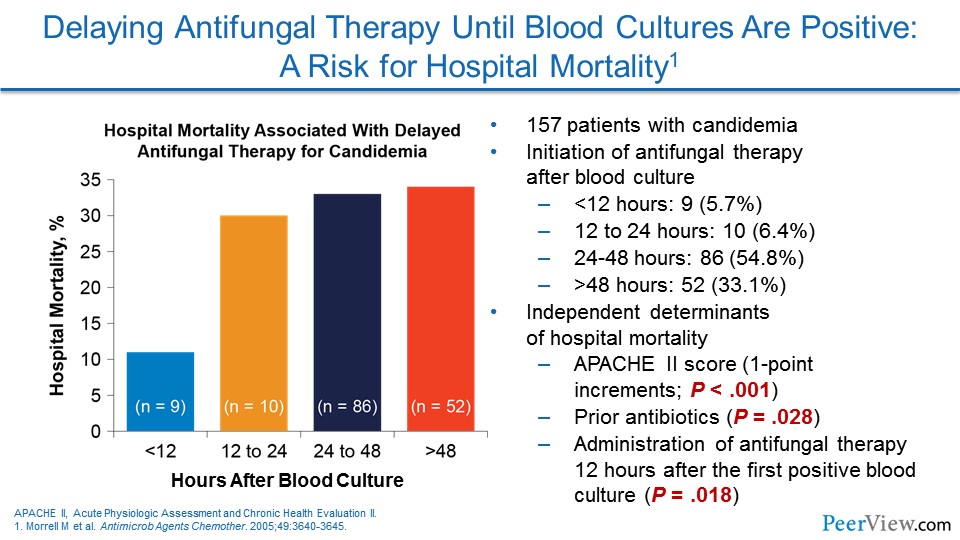

Dr. Patterson: I think the data that we have seen from Washington University in St. Louis by Morrell and colleagues showed, you know, a number of years ago the importance of early initiation of therapy, even back then, with fluconazole, and I think the data are also clear now with the echinocandins, that early therapy really improves mortality in that patient population. And a number of studies have shown that echinocandin use is associated with decreased mortality in that high-risk patient population. So, it is really important. I think for Candida, unfortunately, the screening tools are not as widely available or well developed.

Slide 9

Dr. Patterson: There are a number of approaches that you can use. As you mentioned, they are not as widely available, but the use of beta-D-glucan testing and early efforts to make a prompt diagnosis from blood cultures, like T2 magnetic resonance technologies—all of those techniques can dramatically improve outcomes in those patients at risk for Candida.

In our setting, for patients at risk for invasive molds, I think the approach is a little different. I think in that setting, prophylaxis, where you treat a number of patients just at high risk, is an important consideration if you carefully stratify for that high-risk event.

I think more importantly is the use of preemptive therapy, where you use surrogate markers, diagnostic tests—be it galactomannan for Aspergillus, beta-D-glucan for invasive molds, or even polymerase chain reaction testing, which is becoming more widely available from body fluids.

I think that scenario of preemptive therapy has largely replaced empiric therapy, because we know now how important evaluation workup is—like in a neutropenic patient with computed tomography (CT) scan and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid examination, bronchoscopy in those patients with abnormal CTs really helps establish a mycologic diagnosis and allows you to target therapy.

Certainly, if your center does not have the availability of diagnostics, then empiric therapy is an approach that you could undertake. That would be where you simply are treating patients, for example, with unresponsive fevers and neutropenia. But otherwise, I think, a preemptive approach is becoming recognized as an important strategy.

Pathogen-directed therapy is useful. Certainly, if you were able to get a culture, then you know for sure what your pathogen is. Now you may have a coinfection, and it is important to keep that in mind. But it is also important then to allow you to do susceptibility testing in those highest-risk patients or in patients who do not respond.

I think in that regard, too, it is important to recognize in those patients who have been on prophylaxis that you have really got to strongly consider what organisms might be breaking through—whether it is a resistant organism, which is less likely, or one that is just not susceptible to the prophylaxis agents the patients are on.

Optimizing Antifungal Therapy in the Hospital Setting: A Closer Look at Current Evidence and a Multidisciplinary Approach to Patient Care

Slide 10

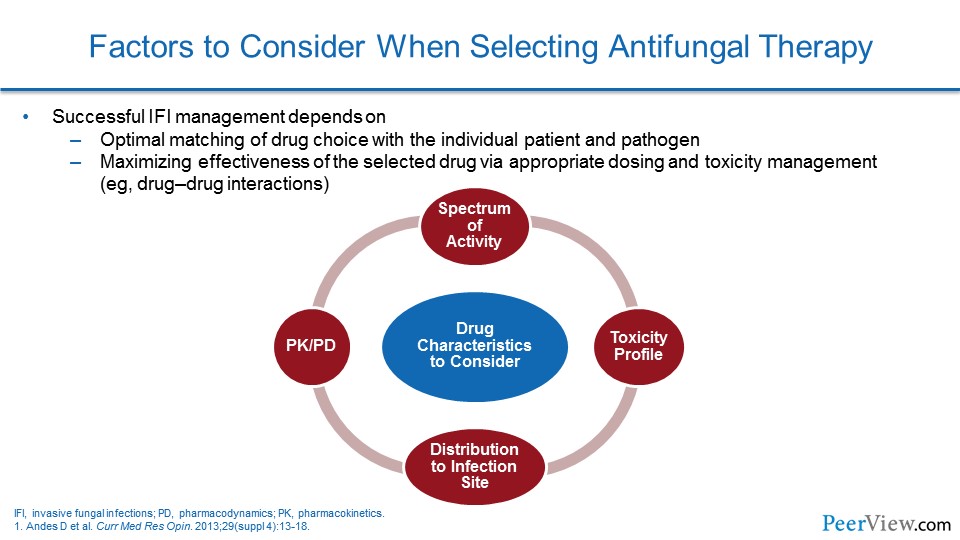

Dr. Patterson: If we turn then to talk about our current treatment options and how you optimally utilize these agents in clinical practice… Can you make a few comments, Jim, about how the antifungal pharmacology has changed now that we have more drugs and choices available, and how you use those in your practice at your hospital?

Slide 11

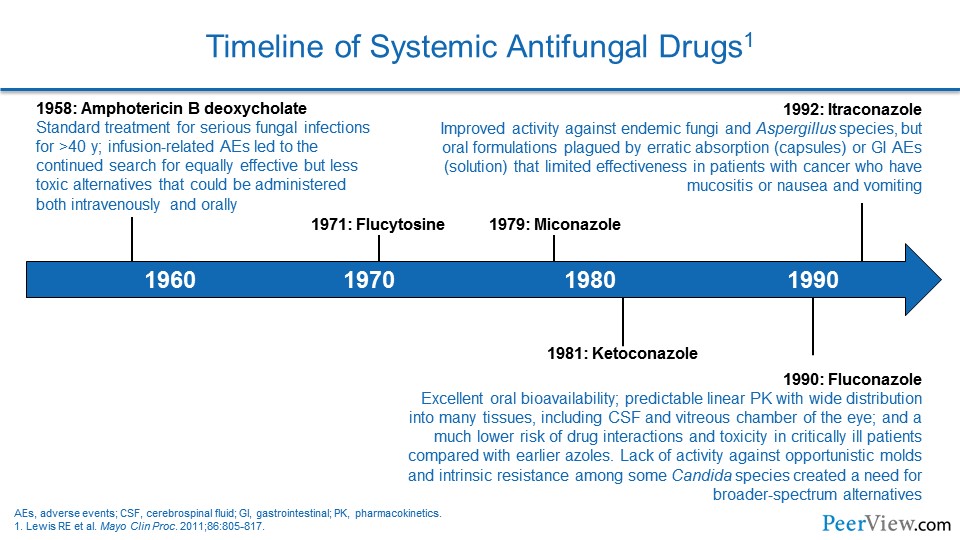

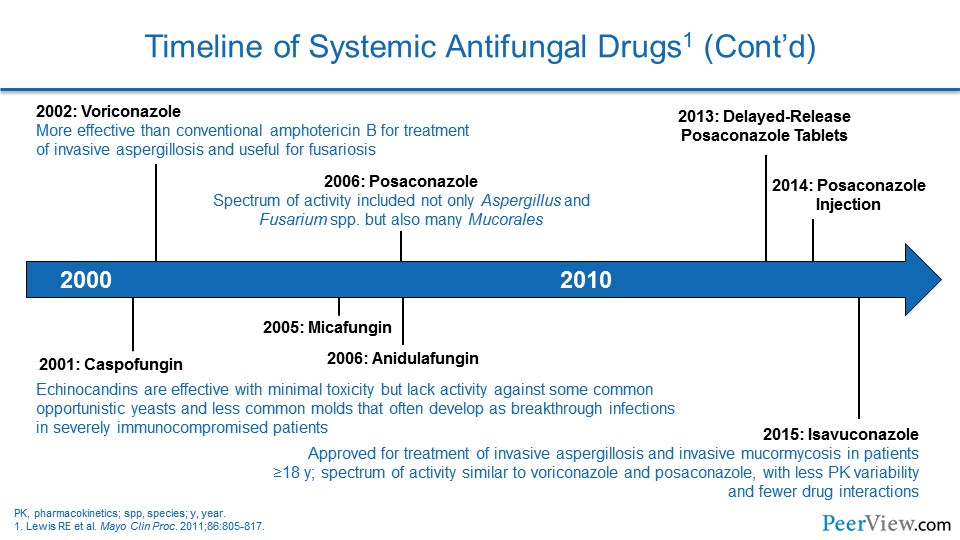

Dr. Lewis: Yeah, it is been really interesting to see how the drug therapy has evolved over the last few years. And I think a lot of it has been driven by a lot of factors that we have kind of talked about previously.

Slide 12

Dr. Lewis: And I think one of the other things that's very interesting—and is a major change from 2009 Candida guidelines to the 2016 Candida guidelines—is really the emphasis on earlier echinocandin therapy. And even in those empirically before you have proven disease, if they are hemodynamically unstable, the recommendation is now for echinocandin upfront. And I think that that is a major departure from what we have seen in previous iterations of the guidelines and is a major practice change for a lot of clinicians and hospital pharmacists as well.

I think the other thing that is important for folks to recognize, though, is that fluconazole remains really an extremely important option for patients who are no longer hemodynamically unstable, who are responding well clinically, and in situations when you have an organism and you know what the susceptibility of that organism is to fluconazole.

There is certainly nothing out there that is saying at this point that we need to be continuing nothing but echinocandins for a full 14 days of therapy in someone who is candidemic. But the emphasis from both the IDSA, as well as the European guidelines, based largely on a data set that was put together by David Andes in 2012, is really pushing us toward echinocandins for everyone up front, because they appear to be associated with better clinical outcomes and improved survival.

And so, I think that is really what has driven that shift away from fluconazole more to echinocandins up front, with the understanding that fluconazole remains an important option as step-down therapy in patients who are clinically stable once you have a better grip on what is going on clinically.

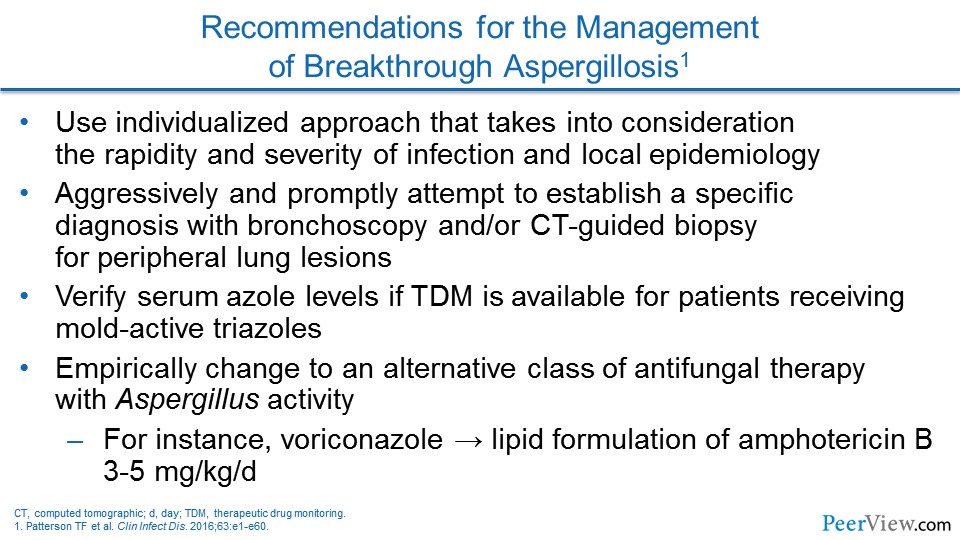

As you kind of alluded to with Aspergillus, Tom, this is, I think, really an interesting area, because the extremely high-risk folks now are getting a lot of these broad-spectrum, newer-generation azoles as prophylaxis. And that is creating some very interesting clinical scenarios when patients who have been on prophylaxis with one of those broad-spectrum azoles now present with something that appears to be an invasive fungal infection. The breakthroughs are becoming more and more challenging, and trying to figure out what is going on—and I think the issue is we are still so stuck, oftentimes, without a diagnosis.

Slide 13

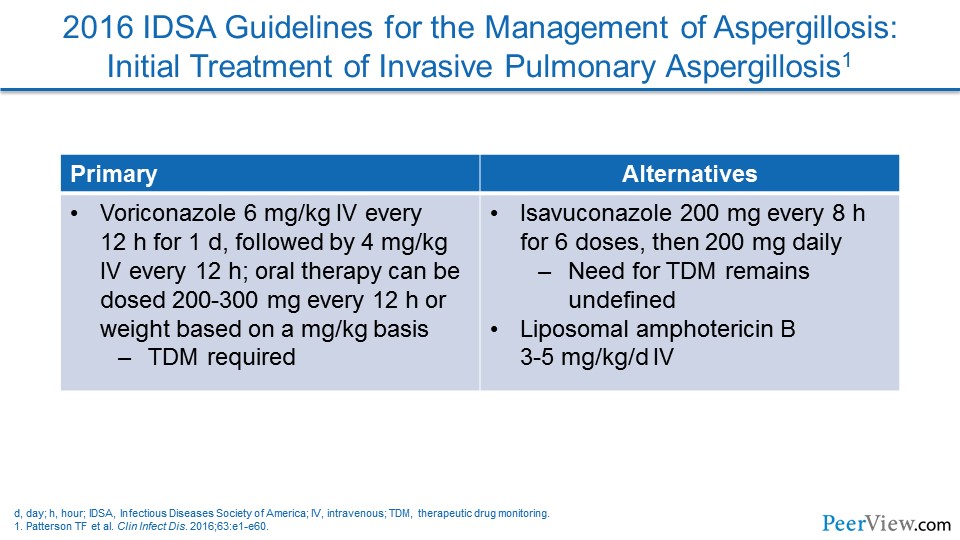

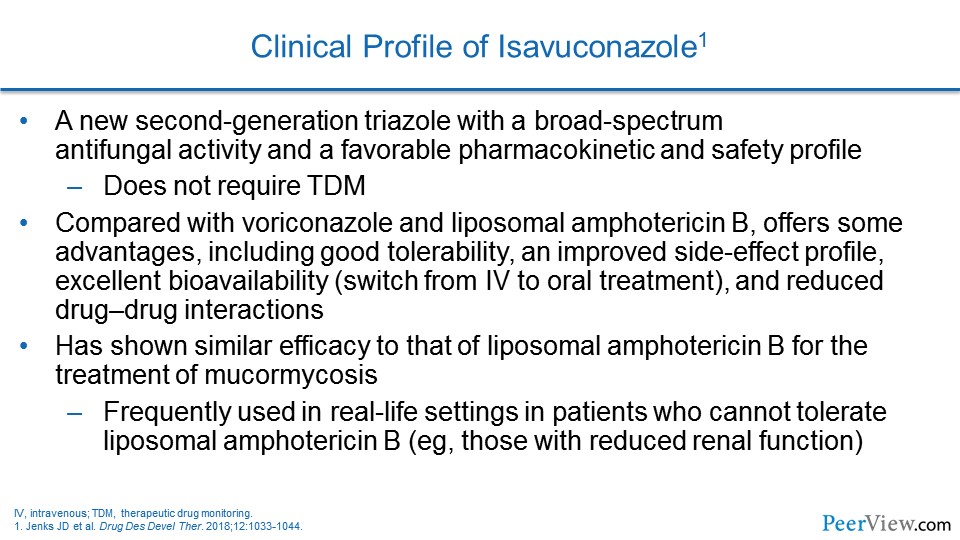

Dr. Lewis: You know, I think it is interesting to look at the Aspergillus guidelines and see that voriconazole and isavuconazole are now preferred for therapy of proven aspergillosis. And I think isavuconazole has been a nice addition to the armamentarium. I think we've always known that voriconazole is a challenging compound because of its nonlinear pharmacokinetics and because of its ability to impact multiple isozymes of the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) system, and isavuconazole appears to work just as well for invasive aspergillosis, but it is a little bit less complicated in that it seems to have fewer drug interactions. It seems to have linear pharmacokinetics, and it doesn't seem to require the therapeutic drug monitoring that voriconazole does. And so, I think that for treatment, voriconazole and isavuconazole are front-line agents, with posaconazole still largely being relegated in most centers to the prophylaxis indications, where it has extensive data and experience at this point.

Slide 14

Dr. Lewis: As you talked about with some of the breakthrough mold infections in folks who have been on these broader-spectrum azoles (eg, voriconazole, posaconazole, isavuconazole) previously, that to me, it is been very interesting to watch the reemergence of amphotericin B in its lipid formulations in that population because I think that we do not really necessarily have a grip on what the true cross resistance between these new-generation azoles looks like in invasive aspergillosis. And a lot of times, we do not have a bug to allow us to do susceptibility testing. And so, because of that, we tend to shift completely away from the azole class over to the lipid preparations of amphotericin B in order to deal with these breakthrough mold infections.

Slide 15

Dr. Patterson: Yes, I would agree. I think in our setting, we have many of those same considerations and concerns. Certainly if you look at the Aspergillus guidelines, even since those were introduced, there are a number of studies that have now addressed the role of isavuconazole in clinical settings.

I think we are now more comfortable with the pharmacology and the bioavailability of the drug, with good levels of the drug in most settings it now seems. Certainly, we will learn more about the need for therapeutic drug monitoring as we gain more experience. But I would agree with you that at the present time, drug levels seem really very good, so that you probably do not need to measure the levels as avidly as you certainly would with voriconazole, and even perhaps posaconazole. I think it is also important to recognize that isavuconazole does have activity against Mucorales, and I think that offers an advantage in some of those very high-risk patients.

Slide 16

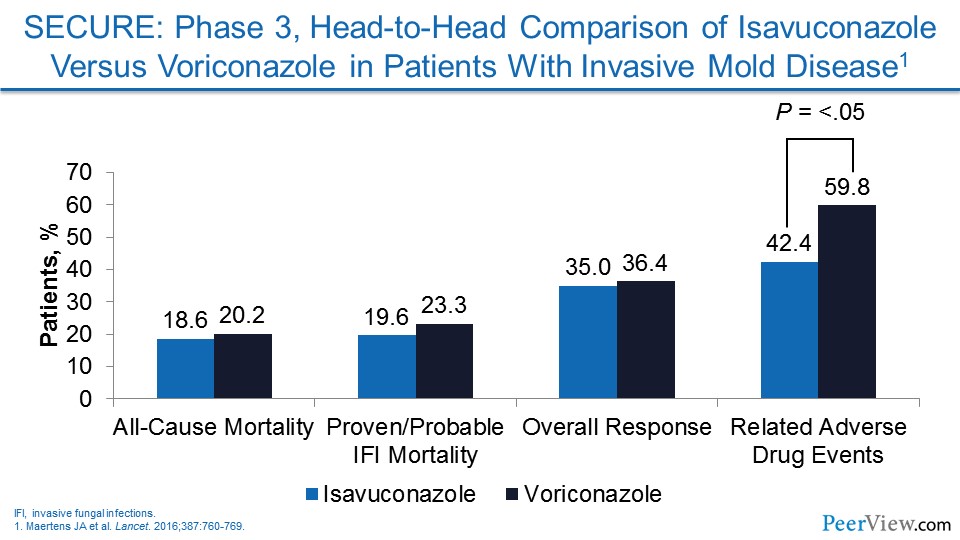

Dr. Patterson: Certainly, the safety of isavuconazole in head-to-head comparisons for Aspergillus and other molds was good, and the adverse events were less with isavuconazole than those was seen with voriconazole. You do have good activity of posaconazole against Mucorales. The spectrum of isavuconazole and posaconazole are similar in that regard. But certainly the drugs are not going to be interchangeable. Some will be more, I think, efficacious and tolerated in certain settings than others. As you mentioned, Jim, it is sometimes complicated because of formularies and cost, and I think those do play into our considerations when being able to prescribe these agents in a real-world setting.

Slide 17

Dr. Patterson: As we conclude our comments, I wonder if you might comment, Jim, about the role and responsibilities of multidisciplinary teams in monitoring and directing appropriate use. That is specifically including pharmacists, infectious disease specialists, and the like. Can you share a few words on your experience?

Dr. Lewis: You know, I think that the level of complexity with these patients is such that the multidisciplinary team is really advantageous. And I think that, again, this is most easily evident in your profoundly immunocompromised patients, in which you have the newer generation of azoles in play.

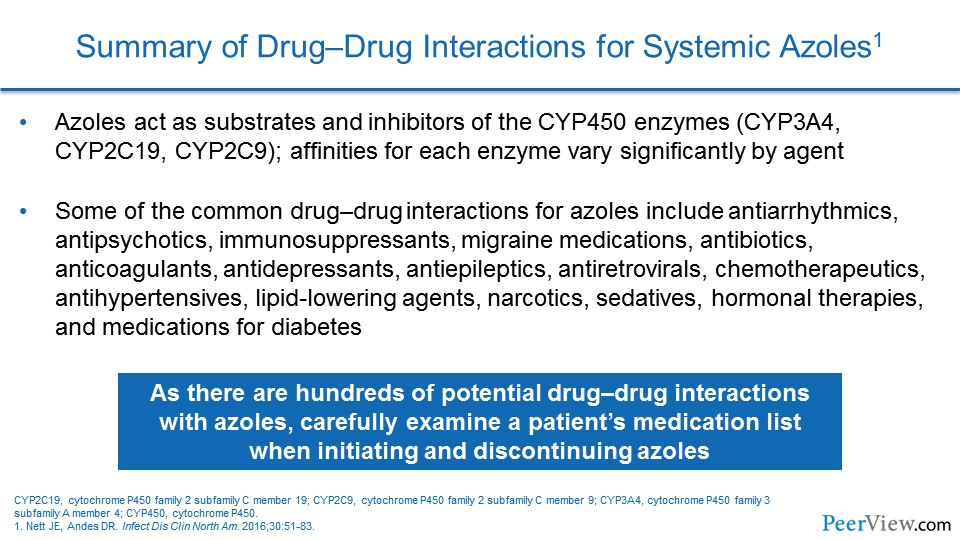

Slide 18

Dr. Lewis: The reason for that is simple: drug interactions. The complexity of the new-generation azoles with regards to the extent and the severity of the drug interactions is such that I think that really this is a very good role for the involvement of your pharmacy colleagues in the care of these patients. Because not only do we have in those groups the CYP450 inhibition that comes along with all of these azoles in play, but the other thing that I have been rather unpleasantly surprised by is with all of these new immunotherapy agents, all of these new chemotherapy agents that are coming along, the level of understanding of the CYP450 involvement with some of these newer compounds, with how fast they are developed, is really challenging.

And so I think one of the real things for both pharmacists and physicians who are taking care of these patients to really keep an eye on is when you are using a drug you have not heard of, you better be real careful with the drug interactions.

Slide 19

Dr. Lewis: The other area though that I think, you know, this becomes really important, even when you are using fluconazole, the CYP450 interactions there, you cannot really take your eye off the ball there in our critically ill population either. And that is really what I think one of the major strengths of the echinocandins is that lack of CYP450 involvement that we see with those compounds. They are much cleaner from a drug interaction standpoint, and, honestly, they make our lives as pharmacists a little bit easier when it comes to all of the interactions that we are trying to manage in these critically ill patients.

And so, I think the involvement of the multidisciplinary team from all of those standpoints is important, but also one of the places that I find the involvement of the multidisciplinary teams extremely important is when you are trying to discharge some of these patients on some of these new-generation azoles, and the involvement of some of our social work and discharge-planning colleagues to try and get the insurances lined up in such a way that we can actually get these patients out the door in a way that they can afford these compounds.

So I think it is both clinical, as well as financial, you know, for our patients that we really need to be thinking about multidisciplinary involvement to optimize the use and to make sure that these agents are getting to the patients who need them.

Slide 20

Dr. Lewis: And then to back up also and put my stewardship hat back on, I think antifungal stewardship is absolutely important. I think that the evolution of C. auris shows us that, you know, putting azoles or echinocandins out there just kind of willy-nilly in critically ill patients is something that should be avoided, because we see C. glabrata with increasing azole resistance. That has been an issue for years. And now the emergence, you know, intercontinentally of this C. auris organism that is, in some of the scarier versions of it, resistant to basically all of our front-line antifungals, I think really places an increased emphasis on the need to make sure that we are doing appropriate antifungal stewardship. And then that circles back to the need for improved diagnostics, which you talked a lot about earlier in our discussion.

Dr. Patterson: Thanks. I certainly concur with your comments in that regard, that the complexity of the patients at risk for invasive fungal infections is really extensive, and it really makes the use of a multidisciplinary team just critical in effective management of these patients.

That ends our discussion for today. Jim, thanks again for all your insights and comments. For our audience, we hope you have found the activity informative and useful to practice.

Narrator: This activity has been jointly provided by Medical Learning Institute, Inc. and PVI, PeerView Institute for Medical Education.