Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Identification and Management of Atopic Dermatitis— Applying Advances to Improve Outcomes: Treatment and Emerging Therapies in Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis

INTRODUCTION TO ATOPIC DERMATITIS: EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Atopic dermatitis (AD), a common variety of eczema, is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease appearing anywhere on the body that affects patients of all ages, primarily children.1 It follows a relapsing course with periods of exacerbations, called flares, and has extended periods of remission. 2 Approximately 60% of patients with the disease present by age one year, and by five years of age, about 90% of affected children are diagnosed.2 The worldwide lifetime prevalence of AD in developed countries ranges from 10% to 20%.3

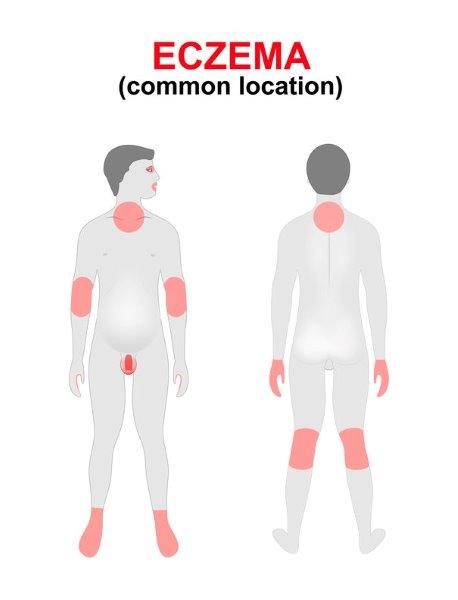

The typical presentation of AD flares varies depending on the age of the patient. Clinical findings include erythema, edema, xerosis (dry skin), erosions/excoriations, oozing and crusting of lesions. Pruritus is a key symptom of AD and contributes to the disease burden. For infants, symptoms typically present early in life, with 60% of patients developing symptoms by one year of age. Infants most often present with an erythematous, papular skin rash on the cheeks and chin, which can progress to red, scaling, oozing skin.4 The location of the rash distribution changes with increasing mobility of the infant. As infants and toddlers start to crawl, AD presents on face, elbows and knees. In children, flares usually appears in the folds of the elbows, hands and/or knees. As patients age, lichenification (thick skin) results from repeated scratching of the skin. In adults, the pattern of the rash is often more diffuse, with the face most commonly involved. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

|

For many children, AD spontaneously resolves before adulthood, but some patients continue to have dermatitis after age 18.1 The estimated prevalence of AD among adults in the United States (U.S.) was 10.2% in a 2010 nationwide survey.5 There is a negative impact on the quality of life for patients and families with social, financial, and academic burden.6

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of AD is multifactorial. Genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors all lead to disruption in skin barrier function and dysregulation of the immune system. On a cellular level, the inflammatory nature of AD is due to infiltration of T cells and monocytes with allergic sensitization inducing chronic inflammation. Furthermore, the ability of CD4+ T cells to recognize non-self and inform adaptive immune responses are impaired in patients with AD.7 Genetic predisposition has a large impact on the likelihood of developing AD.1 Children have a greater than 80% chance of developing AD when both parents have a history of the disease. A maternal history is more predictive of the development of AD than a paternal history. Mutations leading to changes in the skin barrier are thought to contribute to this genetic component. Filaggrin is a protein present in the epidermis, which undergoes processing to maintain the normal function and hydration of the skin barrier. Several loss of function mutations in filaggrin have been identified in the disruption of normal process affecting skin pH, promotion of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, and unimpeded growth of Staphylocccus aureus.7 In addition to genetic factors, any history of atopic disease, including food allergy, asthma, or allergic rhinitis, is a strong risk factor. The clinical progression from one atopic disease to another is referred to as the “atopic march.” This progression does not occur in all patients and the mechanism of the association is complex and not well understood.2

Environmental factors are also thought to contribute to the complex pathogenesis of the disease. Increased latitude, colder temperatures, and low ultraviolet light exposure have been associated with increased AD symptoms.8 Prevalence of AD is higher in children in urban areas and in areas with pollution. While it is evident that certain sources of food can contribute to an AD flare, there is no evidence that early introduction of certain foods in infants to help decrease the risk of AD development.2

Disease Burden

Atopic dermatitis has a significant impact on the quality of life of patients and their families. The estimated annual expenditure of AD in the US for 2015 was about 5.2 billion dollars.6 One study estimated the annual direct health care costs for AD patients at anywhere from $71 to $2559 per patient. These estimates do not incorporate the indirect costs, such as missed work for patients or caregivers, which would significantly increase economic impact of the disease state.9 Additionally, these figures may not capture the rising costs of the development of novel, expensive medications. Aside from a financial impact, patients and their families are impacted physically, emotionally, and socially. One study conducted direct focus sessions with patients with AD and their parents, evaluating effects on physical health, physical functioning, emotional health, and social functioning thoroughly. Physical effects associated with AD include itching, scratching, sleeplessness, bleeding skin, and pain. Significant physical impairments in children included clothing restriction, interference with outdoor play, limitations in swimming activities, and restrictions on baths. Parents similarly reported limited time for vacations with family, reduced work hours, increased time spent on treatment, and difficulty finding childcare. Su, et al conducted a study to assess impact on families with children with AD. In 48 children included in the study, they estimated families spent a mean of 2 to 3 hours on treatment daily.10 The time spent on treatments limits time available for other daily activities. Emotional impact of AD includes a higher likelihood of developing irritability, hyperactivity, frustration, and attention seeking. Parents felt disappointed, helpless, and worried about the cost of treatment and the child’s ability to make friends. Parents also felt increased strain on relationships with spouses.11 Additionally, in adult patients, certain careers were avoided due the presence of AD. Others believed it hindered career progression in addition to overall school or work life.6

The most burdensome symptoms in patients affected with AD are sleep disturbance and pruritis. Sleep disturbance is commonly caused by significant itch associated with AD and is reported to be disrupted in up to 60% of children with eczema, increasing during exacerbation episodes.2 In a population-based cross-sectional cohort study conducted in adults, the most burdensome symptoms reported in patients with AD were itch (54.4%), followed by excessive dryness or scaling (19.6%), and red or inflamed skin (7.2%).12

As previously discussed, patients often present with multiple atopic conditions. Beyond these, there are a variety of other comorbid conditions that are associated with the presence of AD. There is an association between AD and the development of diabetes. Possible associations for this link that have been studied include the treatment with steroids, a genetic predisposition, sedentary lifestyle, or systemic low-grade inflammation.13 There is an unclear association in patients that develop cardiovascular disease and AD.

Additional comorbid conditions observed in patients with AD include other immunologic diseases. This could be related to an already disrupted immune system. Commonly, AD has been associated with alopecia areata, vitiligo, lupus erythematosus, and chronic urticaria. Furthermore, positive associations have repeatedly been demonstrated between AD and inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus. The pathophysiology of these associations involves a pro-inflammatory state, environmental exposures that may trigger immune diseases, and genetic risk, as multiple immunologic diseases tend to occur together. Finally, depression, anxiety, and pediatric neurologic conditions occur together in patients with AD.13

Clinical Presentation and Disease Severity Classification

Diagnosis of AD is made based on clinical assessment of a patient’s skin.2 There are formal sets of criteria available, but these have not been universally adopted. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines suggest the following criteria: presence of pruritus and eczema with typical morphology and patterns, supported by the age of onset, history of personal or family atopy, and xerosis (dry skin), with other similar dermatologic conditions excluded.

Disease severity is commonly assessed using The SCORing of Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index.14 In this method, the clinician rates subjective and objective criteria to evaluate severity of disease. These criteria include areas of involvement, characteristics and intensity of visible symptoms, and assessment of subjective symptoms, including itch and sleep disturbance. A score of greater than 50 is indicative of severe disease, and less than 25 is considered mild AD. Severity scores can be utilized to guide escalation and de-escalation of treatment throughout a patient’s clinical course. Other available scales include the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), for assessing visible lesions only, as well as the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), for assessing subjective measures only.

Madison is a 2-year-old female recently diagnosed with atopic dermatitis. Based on the SCORAD index, her disease severity is currently classified as mild. Her mother asks you, the pharmacist, how to treat the affected areas on Madison’s face. She also inquires what she can do to prevent future flares once this episode resolves. What do you recommend at this time?

Initial Therapy

Management of AD centers around several core goals: providing symptomatic relief, controlling AD manifestations, minimizing any triggers or predisposing factors, and preventing future exacerbations.4 Based on the evolving nature of AD, treatment can change over time. For all patients, good skin care practices are recommended and should be highly encouraged by pharmacists.

Treatment of AD is a stepwise approach, as outlined in the diagram below. Initial management involves non-pharmacologic therapy, followed by topical therapy with active agents, and, if necessary, progresses to systemic therapy. Management is individualized based upon disease severity, patient response, and tolerance. All patients should implement non-pharmacologic therapy and emollient application throughout their disease course, and, during flares, monotherapy or combination therapy may be implemented, as appropriate.

Non-pharmacologic management of AD is focused on bathing, with an emphasis on cleansing affected areas.15 This practice is beneficial for removal of crusts and minimization of bacterial contamination. Although bathing is a key aspect of non-pharmacologic care, frequency of bathing is debated, leading to inconsistent guideline recommendations. Associated risks include aggravation of symptoms resulting from skin barrier breakdown, although this may be more likely attributable to overuse of detergents and excess towel drying. Most specialists recommend once-daily bathing with warm water and gentle cleansers.16 In addition to traditional cleansing with low-irritant cleansers, bleach baths using dilute sodium hypochlorite solution may be utilized to inhibit bacterial growth, while salt baths may be useful for removing dead skin cells.17,18 For bleach baths, pharmacists may recommend adding ¼ to ½ cup of household bleach, about 6% sodium hypochlorite solution, to a bathtub full of water. Patients should be instructed not to bathe for more than 10 minutes and should avoid exposing bleach directly to the face, especially the eyes. For salt baths, patients may add a cup of table salt, sea salt, or Epsom salt to a bathtub full of water prior to bathing.

Following bathing and patting skin dry, emollient application is crucial to prevent and treat skin dehydration. Emollients are topical preparations of oils mixed with water in varying proportions to create ointments, gels, creams, and lotions. They function as the cornerstone of AD management and should be utilized in conjunction with mild, moderate, and severe treatment options as well as in between AD flares for prevention. Patients should apply emollients generously, multiple times per day, and use should be continued indefinitely. Maintaining hydration of the skin is an essential aspect of AD management, and adherence to therapy may lessen disease severity. While many different types of emollients are available, they all mechanistically function by topically rehydrating the skin to prevent water loss through evaporation, which soothes and relieves itch.19 The choice of emollient product is multifactorial but most commonly dictated by patient preference. Ointments have the highest oil content and are useful for very dry and thickened areas. Gels have less oil content and are relatively light in relation to ointments. Creams are approximately half water and half oil and can be used over weeping skin. Lotions are composed of greater amounts of water and less oil, which enables easy spreading and absorption, especially for hairy areas of the body.20

If skin sensitivity occurs, switching to another product or formulation may be beneficial, as this reaction is mostly attributed to additives in the formulation. Folliculitis may occur, though this adverse effect occurs more commonly with occlusive agents and may also be product-dependent.7 When used in conjunction with other topical therapies, a period of about 20 to 30 minutes should be allotted between application times to prevent the unintentional spread of active agents to other areas of the body. Order of application has not demonstrated an effect on treatment outcomes.21

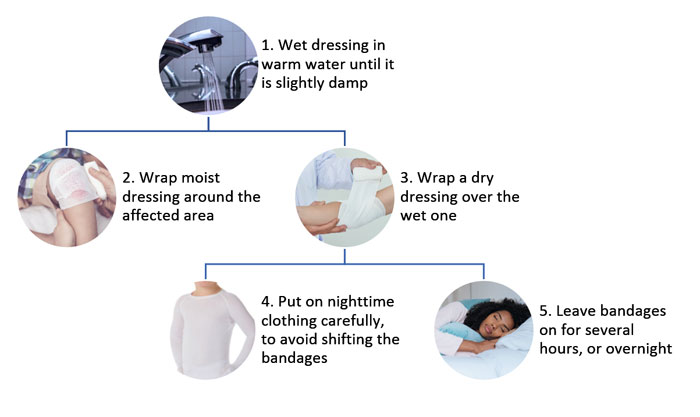

Wet Wrap Therapy (WWT)

Wet wrap therapy can be used with pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic options to quickly decrease the severity of AD and during the treatment of significant flares. Patient can be instructed to moisten a topical dressing with warm water (Figure 2). This damp dressing is then wrapped around the affected area over any topical agents that the patient is instructed to apply. Atop the damp layer, patients should wrap a dry dressing, followed by dry clothing. This therapy should remain on the patient for several hours or overnight, and application can be repeated for 3 to 14 days. This technique is most useful in patients with acute, oozing and erosive lesions that do not tolerate topical pharmacologic therapy. Wet wrap medications can help improve tolerance of the topical therapy; however, this is not a standardized treatment and lacks high quality evidence.2,14

Figure 2

|

A few months later Madison’s mother comes back to your pharmacy seeking advice. She has been bathing Madison daily and providing aggressive emollient application, but Madison is still symptomatic. How would you recommend she escalate care of her child?

Management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis

When response to initial therapy is inadequate, active pharmacologic agents are recommended in addition to bathing and emollient application. Topical pharmacologic therapy options remains the backbone of therapy for moderate-to-severe AD in both children and adults.2 For pharmacologic management, a stepwise approach is recommended starting with topical corticosteroids (TCSs).2 The robust, long-standing data on TCS efficacy and safety makes this treatment modality the preferred option for AD flares. If TCSs fail or are not suitable, topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCNIs) are another topical anti-inflammatory medication that can be used as a second-line option in most patients. Topical therapy is most effective when three general principles are followed: sufficient strength, sufficient dosage, and correct application.14

Topical Corticosteroids (TCSs)

Topical corticosteroids remain the mainstay of topical anti-inflammatory therapy in patients with AD. The mechanism of TCSs is to interfere with antigen processing and suppressing the release of proinflammatory cytokines and ultimately reducing inflammation.2 They are proven to decrease acute and chronic signs of AD and can be used for the treatment and preventions of flares. There are a variety of TCSs, dosage formulations, and potencies available. The potency of TCSs ranges from very low potency to very high potency (Table 1).22 There is limited evidence to recommend optimal potency, dosage form, frequency, and dose of TCSs. Patient preference and experience may guide the choice of agent, dosage form, and dose.

| Table 1: Topical Corticosteroids21 |

| Potency |

Drug Name |

Strength |

Dosage Form |

| Very High Potency |

Betamethasone dipropionate |

All 0.05% |

Gel, lotion, ointment |

| Clobetasol propionate |

Cream, foam, gel, lotion, ointment, spray |

| Diflorasone diacetate |

Ointment |

| Halobetasol propionate |

Cream, ointment |

| High Potency |

Amcinonide |

0.1% |

Cream, ointment, lotion |

| Betamethasone dipropionate, |

0.05% |

Cream |

| Betamethasone dipropionate |

0.05% |

Cream, ointment |

| Betamethasone valerate |

0.1% |

Ointment |

| Desoximetasone |

0.05% |

Gel |

| Desoximetasone |

0.25% |

Cream, ointment |

| Diflorasone diacetate |

0.05% |

Cream, ointment |

| Fluocinonide |

0.05% |

Cream, ointment, gel |

| Halcinonide |

0.1% |

Cream, ointment |

| Triamcinolone acetonide |

0.5% |

Cream, spray |

| Intermediate Potency |

Betamethasone dipropionate |

0.05% |

Lotion |

| Betamethasone valerate |

0.1% |

Cream |

| Clobetasone butyrate |

0.05% |

Cream |

| Clocortolone pivalate |

0.1% |

Cream |

| Desoximetasone |

0.05% |

Cream |

| Diflucortolone |

0.1% |

Cream, oily cream, ointment |

| Flumethasone pivalate |

0.02% |

Cream |

| Fluocinolone acetonide |

0.025% |

Cream, ointment |

| Flurandrenolide |

0.05% |

Cream, ointment, lotion, tape |

| Fluticasone propionate |

0.005% |

Ointment |

| Fluticasone propionate |

0.05% |

Cream, lotion |

| Hydrocortisone butyrate |

0.1% |

Ointment, solution |

| Hydrocortisone valerate |

0.2% |

Cream, ointment |

| Mometasone furoate |

0.1% |

Cream, ointment, lotion |

| Prednicarbate |

0.1% |

Cream, ointment |

| Triamcinolone acetonide |

0.025% |

Cream, ointment, lotion |

| Triamcinolone acetonide |

0.1% |

Cream, ointment, lotion |

| Low Potency |

Alclometasone dipropionate |

0.05% |

Cream, ointment |

| Desonide |

0.05% |

Cream, ointment |

| Fluocinolone acetonide |

0.01% |

Cream, solution |

| Hydrocortisone |

0.5% |

Cream, ointment, lotion |

| Hydrocortisone acetate |

0.5% |

Cream, ointment |

| Hydrocortisone acetate |

1% |

Cream, ointment |

| Hydrocortisonea |

1% |

Cream, ointment, lotion, solution |

| Hydrocortisone |

2.5% |

Cream, ointment, lotion |

General recommendations include the use of low-potency TCSs for maintenance therapy and medium-to-high potency TCSs for treatment of acute flares.23 Alternative methods include using low potency products for all flares and increasing the potency if the initial treatment fails. Most TCSs are recommended to be applied twice daily; however, there is literature that suggests once daily application may be appropriate. Daily application is recommended for the treatment of severe acute flares until resolution is observed.2 For more mild flares or maintenance, application can be two to three times weekly. Monthly totals for mild disease should average about 15 grams in infants, 30 grams in children, and up to 60 to 90 grams in adolescents and adults.14

Resolution of acute flares is monitored by the presence of itch. Topical corticosteroids should not be tapered or discontinued prior to the resolution of itch in the affected areas. After resolution, tapering has been suggested despite any definitive evidence. Continuing low-potency TCSs at weekly or twice weekly administration frequencies after resolution of the flare can be beneficial to help reduce the occurrence of flares.2,14 Long-term use of TCSs has been not been studied to best recommend a duration for preventive therapy.

Adverse effects of topical therapy are mostly limited to changes in the skin. Local adverse effects include cutaneous atrophy, erythema, and hypopigmentation. Caution should be taken with the use of potent TCSs on areas of thin skin, such as the face, neck, and skin folds because of increased absorption in these areas and risk of skin atrophy. In children, it is important to advise parents to use the minimum amount of TCS necessary, especially when using the high-potency TCSs because smaller children are at increased risk of systemic absorption because of proportionately higher body surface areas.14 TCS withdrawal can occur upon discontinuation of therapy and presents with rosacea-like dermatitis, burning, and stinging.24 Severity of exacerbation of symptoms after discontinuation of TCSs is correlated with the duration of treatment. Although rare, systemic adrenal suppression can occur with the use of very high-potency corticosteroids applied topically.25

When patients are unsure how to apply the TCS, the following method of application may be suggested, referred to as the Fingertip Unit (FTU). Patients should estimate 0.5 grams as the amount from a tube with a 5 mm nozzle dispensed from the distal interphalangeal joint to the fingertip which equals one FTU. One FTU is enough to apply over the area of the size of two adult palms or 2% of body surface.14

Finally, a key role of pharmacists in caring for patients with AD being prescribed TCSs is to address “corticophobia.” In a study of adult patients and parents of children with AD, 80.7% of respondents reported having fears about TCSs and 36% admitted nonadherence to treatment due to fears.26 It is crucial for pharmacists to counsel patients on the low risk of adverse effects as well as the importance of medication adherence to effectively manage the disease.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (TCNIs)

Two TCNIs, tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream, are approved for use for the treatment of AD for short-term and long-term use in adults and children. Tacrolimus comes in 0.03% and 0.1% strength – the 0.1% strength is comparable to mid-potency TCSs. Pimecrolimus 0.1% is considered less efficacious than mid-to-high potency TCSs. Topical calcineurin inhibitors work by suppressing activation of T-cells and mast cells and by blocking the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.2

Topical calcineurin inhibitors are recommended as second-line agents when TCSs are ineffective. TCNIs are preferred in select patients, including those who have flares in sensitive areas such as the face or skin folds, in patients with long-term TCS use, or in patients who experience atrophy from TCS use.2 Twice-daily application is recommended for use during acute flares of AD. After the flare has resolved, continued use two to three times weekly has demonstrated a reduction in relapse of AD and can be cost-effective.27

Adverse effects of TCNIs include burning and stinging at the site of application, but these adverse effects decrease with continued use.2 Pharmacists can play in a role in ensuring patients understand to continue therapy to maintain control of the disease. Concerns with the use of TCNIs include the risk of increased viral cutaneous infections. While some patients on TCNIs have experienced viral cutaneous reactions, there seems to be no definitive increased risk with the use of TCNIs.14 Furthermore, patient should use ultraviolet protection with sunscreen while on TCNIs due to the boxed warning regarding risk of malignancy. It is important to counsel patients that the association with TCNIs and malignancy has not been validated in clinical trials.14 These discussions may help patients feel more comfortable about the black-box warning, which may lead to improved adherence.

Topical Phosphodiesterase Inhibitor

Crisaborole is a phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor approved for the treatment of mild to moderate AD in patients who are two years of age and older. By inhibiting PDE-4, nuclear factor-kB and activated T-cell signaling pathways are downregulated, suppressing the release of cytokines.28 Two randomized controlled trials were conducted, including 764 total patients. A greater percentage of patients in the crisaborole arm were able to achieve reduction in disease severity and pruritis in a significantly faster period of time than patients utilizing the placebo vehicle.28 Due to the low systemic absorption of the drug, there were minimal treatment-related adverse effects reported. The most common adverse effects include application site burning or stinging, which occurs in less than 1% of patients. Long-term tolerability and safety was demonstrated in an open label 48-week safety study.23

Crisaborole offers an option for patients with mild-to-moderate AD who have safety concerns with the use of alternative anti-inflammatory agents. It has not been studied against TCNIs or TCSs, so it cannot be recommended in comparison to alternative agents.

Phototherapy

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation targets immunomodulation through apoptosis of inflammatory cells.29 UV therapy is considered a second-line therapy for chronic, pruritic forms of atopic dermatitis that are diminished during sunny days.14 Narrowband UVB is preferred over broadband UVB due to safety concerns, and medium-dose UVA1 is similar in efficacy to narrowband UVB. UV therapy may put patients at risk for long-term skin aging and skin cancer; however, this is more commonly observed when used in combination with oral or topical photosensitizing medications. Contraindications to therapy include inherited and acquired disorders that may be worsened by UV light, such as lupus erythematous.30 During phototherapy, pharmacists should counsel patients to avoid topical immunosuppressants, but topical steroids and emollients should be continued to prevent potential flares in disease activity.

Justin is a 15-year-old male who has been struggling with atopic dermatitis management for many years. He failed to respond to high-potency topical corticosteroids and has had an inadequate response to other topical agents. His SCORAD index is > 50, resulting in a severe classification. His dermatologist calls your pharmacy seeking advice about available systemic options. What are some agents you can recommend?

Systemic Immunomodulators

In severe cases of atopic dermatitis, patients are often refractory to topical therapies, and systemic immunosuppression may be necessary to manage symptoms. While evidence is limited, especially in the pediatric population, emerging studies in recent years have provided novel therapeutic options for severe disease. Pharmacists are a valuable resource in the guidance of dosing and monitoring of these medications, especially since they are not approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in this disease state.

Cyclosporine (CsA)

Cyclosporine A is a systemic calcineurin inhibitor that inhibits transcription of proinflammatory cytokines, effectively inhibiting activation of T cells.31 A pooled meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of CsA in severe AD demonstrated a relative effectiveness of 55% after 6 to 8 weeks of therapy. The response was identified to be dose-related with greater reductions in disease severity at greater than or equal to 4 mg/kg. While higher initial doses are generally more efficacious, dosing is limited by the medication’s adverse effect profile.32 Adverse effects are more likely to occur in older patients (45 years of age or older) and with higher doses. The most commonly reported adverse effects that result in drug discontinuation include significant increases in serum creatinine levels, hypertension, and gastrointestinal symptoms. As with all immunosuppressant agents, patients are at increased risk for infection. Patients may also be at increased risk of malignancy, and phototherapy should be avoided as well as excessive sun exposure. Pharmacists should counsel patients on the potential for nephrotoxicity and instruct patients to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Serum creatinine levels should be monitored routinely to detect renal dysfunction. Various brand names, Neoral®/Gengraf® (CsA modified) and Sandiummune® (CsA non-modified), are not interchangeable due to differences in bioavailability, and pharmacists should ensure that the appropriate brand is dispensed. Duration of therapy is typically targeted to last 2 years, but disease control, adverse effects, and ineffectiveness may result in early discontinuation.14,32 Many patients experience prompt relapse upon discontinuation and other therapeutic options must be explored.

Azathioprine (AZA)

If CsA is intolerable or ineffective, AZA is an option for adult and pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis.14 It inhibits proliferation of T cells and B cells on account of DNA/RNA synthesis and repair inhibition.33 Randomized, controlled studies in adults demonstrate greater efficacy compared to placebo as well as comparable efficacy compared to methotrexate (MTX).14 Although patients report improvement in symptoms, therapy is limited by azathioprine’s adverse effect profile.34 Adverse effects associated with medication discontinuation include gastrointestinal disturbances, leukopenia, and hepatotoxicity. Pharmacists can suggest dividing doses or administering doses with food to minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects. There is also a risk of infection and malignancy associated with chronic use. Phototherapy is not recommended with AZA because there may be increased risk of DNA damage and carcinogenesis. Patients should limit UV exposure and utilize appropriate sun protection, including sunscreen with an SPF of 30 of higher. Myelotoxicity may occur, especially in patients with thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) polymorphism, and dose reductions should be considered in patients with reduced TPMT activity.35 Of note, it may take a minimum of four weeks for patients to clinically respond to therapy.14

Mycophenolate Mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is another immunosuppressive agent that can be utilized to manage symptoms of atopic dermatitis, though there is minimal prospective evidence available to demonstrate efficacy.14 It exerts immunomodulatory effects by blocking inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase. The most commonly experienced adverse effects are nausea and diarrhea, although anemia, hypertension, and infection are also observed, particularly in pediatric patients.36 Dosing may need to be adjusted for neutropenia or anemia. Immunosuppression because of MMF may put patients at increased risk of malignancy and other serious infections. Therapy should be discontinued at least 6 weeks prior to a planned pregnancy, as MMF is teratogenic and contraindicated in pregnancy. Similar to CsA, there are two formulations of mycophenolate, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF, CellCept®) and mycophenolate sodium enteric coated (Myfortic®), and pharmacists should ensure these brands are not used interchangeably due to differences in dosing and rate of absorption.

Methotrexate (MTX)

Methotrexate (MTX) is utilized in clinical practice in patients with adult-onset atopic dermatitis; however, literature to support use in pediatric disease is limited.36 One pediatric, prospective, multicenter study compared MTX to CsA and demonstrated no statistically significant difference in efficacy between the two groups at 12 weeks.37 Though its mechanism in AD is not fully known, MTX works by binding irreversibly to inhibit dihydrofolate reductase. It may affect immune function and display anti-inflammatory properties by means of interference of T-cell activation. Due to its mechanism of action, folic acid supplementation may be required to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The most commonly reported adverse effects in studies include nausea, anemia, and fatigue. Bone marrow suppression, aplastic anemia, and gastrointestinal toxicity have been reported with concomitant administration of some NSAIDs. With prolonged use, hepatotoxicity may occur, and pneumonitis may occur at any point during therapy. As with most immunosuppressive therapies, patients may be at increased risk of malignancy and infection. Methotrexate, like MMF, is teratogenic and contraindicated in pregnancy.14 Unlike the other immunosuppressive agents, MTX is dosed weekly rather than daily. Ensuring appropriate prescribing and administration is an important role for pharmacists.

Justin’s dermatologist decides to start him on systemic cyclosporine. He comes to your pharmacy to pick up his prescription. What are some counseling points you can provide to Justin about cyclosporine as well as overall management of his flare?

BIOLOGIC AGENTS

Biologic therapies work by targeting inflammatory cells and cell mediators to reduce inflammation. Similar to systemic immunosuppressant agents, these medications can be considered in patients who are refractory to topical therapy. To date, only one biologic agent, dupilumab, is approved for treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Dupilumab (Dupixent®)

Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin (IL)-4-receptor-α and blocks the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. In March 2017, it became the first biologic approved by FDA for treatment of adults with moderate-to-severe AD.38 Th2-signature cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13, have recently been identified as key mediators in atopic dermatitis. These cytokines modulate inflammatory response and production of filaggrin, which can lead to skin barrier defects in active AD.39 Dupilmab normalizes expression of these cytokines, and, in clinical trials, demonstrated reversal of barrier abnormalities. Efficacy and safety has been demonstrated in four phase III clinical trials, including one trial that assessed patients over a one-year period.38 In this study, all subjects were given concomitant topical corticosteroids with or without topical calcineurin inhibitors. These topical products were tapered, stopped, or started based on disease activity in each individual subject. A statistically significant improvement in symptoms was observed in the dupilumab-treatment arm versus placebo. The most commonly noted adverse effects were injection-site reactions and conjunctivitis, and no significant laboratory abnormalities were noted. These trials established a recommended dose of an initial 600 mg, given as two 300 mg subcutaneous injections, followed by 300 mg every other week. If a dose is missed, a catch-up dose can be given if within 7 days of the missed injection. If the missed dose is not given within 7 days, the dose should be held, and the original schedule should be resumed. A small case-series conducted in six pediatric patients demonstrated efficacy with adult dose used in patients greater than or equal to 40 kg and half-dose in patients less than 40 kg.40 No adverse effects were reported, but additional data is needed to establish safety in this population.

Limitations in the use of dupilumab include high cost and lack of long-term safety data. Patients may also express fear of injections. Pharmacists can address this fear by counseling on proper subcutaneous injection technique as well as the potential benefit of medication adherence. The current recommendation for place in therapy is following optimization of topical therapy and after treatment failure of one or more oral immunosuppressive drugs.39

Mary is a 22-year-old female with a longstanding history of poorly controlled atopic dermatitis. Her physician wrote a prescription for dupilumab, but Mary is apprehensive about starting a new medication, especially an injection. What are some counseling tips you can provide to ease her apprehension?

Emerging Therapies

New therapies are being studied and evaluated for efficacy in AD. It is important for pharmacists to be aware of potential novel agents that may provide more treatment options in patients.

| Emerging Therapies for Atopic Dermatitis |

| |

Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors |

PDE-4 Inhibitors |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) |

Anti-Interleukin (IL) 13 |

Anti-IL 31 |

| Mechanism |

Decreases the signaling of cytokines |

Inhibits nuclear factor-kB and activated T-cell signaling pathways which suppresses the release of cytokines |

Reduces expression of cytokines and inhibition of T-cells |

IL13 which is thought to be overproduced in AD and decreases skin barrier integrity |

Blocks the production of pruritogenic inflammatory cytokines |

| Topical Agents |

DRM02 |

E6005 (RVT-501) OPA-15406 |

Benvitimod |

None |

None |

| Systemic Agents |

Tofacitinib Ruxolitinib |

Apremilast Roflumilast |

None |

Lebrikizumab Tralokinumab |

Nemolizumab |

Emerging topical treatment options include medications that target the JAK receptor, an signal transducer and activator of transcription pathways. Targeting these kinases would ultimately decrease the signaling of cytokines that are present in AD. Tofacitinib and ruxolitinib are JAK inhibitors available for other disease states that show some early benefits in patients with AD in clinical trials. DRM02 is a topical kinase inhibitor currently being evaluated as an option for the treatment of patients with AD. Topical PDE-4 inhibitors, E6005 (RVT-501) and OPA-15406, are also being evaluated as alternatives to FDA-approved crisaborole. Roflumilast is a PDE-4 inhibitor available orally for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. It was previously studied as a topical agent in patients with AD; however, it did not show enough of a benefit compared to placebo. Further trials of roflumilast are necessary to consider it as an agent for AD. Apremilast is an oral PDE-4 inhibitor used off-label for AD. Benvitimod is a NSAID molecule under investigation for topical use in AD. Its mechanism is a reduction in expression of cytokines and inhibition of T-cells.32 Lebrikizumab and tralokinumab are anti-IL-13 agents in phase 2 studies. IL-13 is thought to be overproduced in patients with AD and reduces epidermal barrier integrity. Nemolizumab is an anti-IL-31 agent, which would block the production of pruritogenic inflammatory cytokines.41

The Role of Pharmacists in AD

Pharmacists play a vital role as part of the interdisplinary team in the care of patients with AD. It is important pharmacists find opportunities to educate patients on the foundation of AD care which includes proper skin care routines including bathing and proper moisturizing. In addition to nonpharmacologic therapies, pharmacists can aid in helping patients identify and encourage avoidance of triggers. When patients start on new therapies pharmacists are key in helping educate patients on the goals of therapies. In addition, pharmacists should monitor response to various therapies prescribed and recommended to patients. As AD is a chronic disease, pharmacists can help patients stay adherent to preventative therapies in between exacerbations. Due to the complexity of the treatment regimens during flares, pharmacists can help patients identify a schedule of medications and treatments that will work with school, work, and other activities of daily living. Furthermore, pharmacists can improve rates of adherence with patients by counseling on adverse effects. This will help manage understanding and expectations of the treatment. Many of the systemic agents can contribute to additive adverse effects with other medications and interact with many other medications. It is important for pharmacist to screen for these interactions to maximize benefit and limit the toxicity.

CONCLUSION

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory condition that significantly affects patients’ lives. Skin care regimens including bathing and emollients are the core foundation of therapy for all severities. Mild atopic dermatitis can be treated with emollients, and topical corticosteroids can be considered. For moderate-to-severe disease, systemic agents including methotrexate, calcineurin inhibitors, azathioprine, and monoclonal antibiotics, such as dupilumab, can be considered. Emerging therapies may provide more treatment options, but data is limited to recommend use. The goals of treatment are to treat the current exacerbation and provide maintenance therapy in-between flares. Eventually, achieving adequate control can change the treatment focus to prevention of exacerbations. An important role of pharmacists is to help patients manage adverse effects and to counsel on adherence of medications in order to successfully treat and prevent flares of disease. Recognition of refractory disease and typical symptoms may help pharmacists counsel patients to seek additional medical help as well as provide valuable input to providers in the modification of therapeutic regimens.

References

- Lawley LP, McCall CO, Lawley TJ. Eczema, Psoriasis, Cutaneous Infections, Acne, and Other Common Skin Disorders. In: Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; . http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2129§ionid=192013524. Accessed December 18, 2018.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):338-351.

- Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, et al. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(4):947-954.

- Law RM, Kwa PG. Atopic dermatitis. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2017: 1619-1626.

- Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1132-1138.

- Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(1): 26-30.

- Lyons JJ, Milner JD, Stone KD. Atopic Dermatitis in Children: Clinical Features, Pathophysiology and Treatment. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015;35(1):161-183.

- Flohr, C, Mann J. New approaches to the prevention of childhood atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2014;69(1):56-61.

- Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: impact on the patient, family, and society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(3):192-199.

- Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, et al. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76: 159–162.

- Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Chren MM. Effects of atopic dermatitis on young American children and their families. Pediatrics. 2004;114:607e11.

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: A population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):340-347.

- Andersen YMF, Egeberg A, Skov L, Thyssen JP. Comorbidities of Atopic Dermatitis: Beyond Rhinitis and Asthma. Current Dermatology Reports. 2017;6(1):35-41.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(5):657-682.

- Cardona ID, Stillman L, Jain N. Does bathing frequency matter in pediatric atopic dermatitis? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(1):9-13.

- Cardona ID, Kempe E, Hatzenbeuhler JR, et al. Bathing frequency recommendations for children with atopic dermatitis: results of three observational pilot surveys. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(4):e194-e196.

- Schneider L, Tilles S, Lio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a practice parameter update 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(2):295-299.

- Krakowski AC, Eichenfield LF, Dohil MA. Management of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. 2008;122(4):812-824.

- Silverberg JI, Nelson DB, Yosipovitch G. Addressing treatment challenges in atopic dermatitis with novel topical therapies. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27(6):568-576.

- Peacock, S. Use of emollients in the management of atopic eczema. Br J Community Nurs. 2016;21(2):76-80.

- Ng SY, Begum S, Chong SY. Does order of application of emollient and topical corticosteroids make a difference in the severity of atopic eczema in children? Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(2):160-164.

- Topical Corticosteroids. Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp. Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Riverwoods, IL. Accessed at: http://online.lexi.com., November 11, 2018.

- Eichenfield LF, Call RS, Forsha DW, et al. Long-term safety of crisaborole ointment 2% in children and adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):641-649.

- Takahashi-Ando N, Jones MA, Fujisawa S, Rokuro H. Patient-reported outcomes after discontinuation of long-term topical corticosteroids treatment for atopic dermatitis: a targeted cross-sectional survey. Drug Health Patient Saf. 2015;7:57-62.

- van Velsen SG, De Roos MP, Haeck IM, et al. The potency of clobetasol propionate: serum levels of clobetasol propionate and adrenal function during therapy with 0.05% clobetasol propionate in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:16-20.

- Aubert‐Wastiaux H, Moret L, Le Rhun A, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a study of its nature, origins and frequency. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:808-814.

- Breneman D, Fleischer AB Jr, Abramovits W, et al. Intermittent therapy for flare prevention and long-term disease control in stabilized atopic dermatitis a randomized comparison of 3-times-weekly applications of tacrolimus ointment versus vehicle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:990-999.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):494-503.e6.

- Brenninkmeijer EE, Legierse CM, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. The course of life of patients with childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(1):14-22.

- Crall CS, Rork JF, Delano S, Huang JT. Phototherapy in children: considerations and indications. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(5):633-639.

- Schmitt J, Schmitt N, Meurer M. Cyclosporin in the treatment of patients with atopic eczema – a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(5):606-619.

- van der Schaft J, Politiek K, van den Reek JM, et al. Drug survival for ciclosporin A in a long-term daily practice cohort of adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(6):1621-1627.

- Nygaard U, Deleuran M, Vestergaard C. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: topical therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233(5):333-343.

- Berth-Jones J, Takwale A, Tan E, et al. Azathioprine in severe adult atopic dermatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(2):324-330.

- Meggitt SJ, Gray JC, Reynolds NJ. Azathioprine dosed by thiopurine methyltransferase activity for moderate-to-severe atopic eczema: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:839-846.

- Slater NA, Morrell DS. Systemic therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33(3):289-299.

- El-Khalawany MA, Hassan H, Shaaban D, et al. Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children: a multicenter experience from Egypt. Eur J 2013;172(3):351-356.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287-2303.

- Ariëns LFM, Bakker DS, van der Schaft J, et al. Dupilumab in atopic dermatitis: rationale, latest evidence and place in therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2018;9(9):159-170.

- Treister AD, Lio PA. Long-term off-label dupilumab in pediatric atopic dermatitis: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;[Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1111/pde.13697.

- Hajar T, Gontijo JRV, Hanifin JM. New and developing therapies for atopic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(1):104-107.

Back to Top