Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Turning the Tide on Venous Thromboembolism Applying Anticoagulation Best Practices to Reduce the Disease Burden

Primary Prevention: Identifying Patients at High Risk for VTE

Slide 1

Dr. Piazza: Hello, I’m Dr. Gregory Piazza from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. Welcome to this educational activity on best practices to reduce the burden of venous thromboembolism (VTE). During this program, I’ll explore the evidence and treatment recommendations for primary and secondary prevention of VTE in patients at high risk.

So we’ll start off with a case vignette. This is the case of a patient, Elyse. She’s a 68-year-old woman with obesity who was admitted to the medical service with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia. She was treated with oral corticosteroids, bronchodilators, and antibiotics, and she responded very well and was able to be discharged after 3 days. While in the hospital, she was receiving prophylactic enoxaparin, 40 mg once daily, but that was stopped at the time of discharge.

Slide 2

At home, she followed her discharge instructions to the letter and convalesced while binge watching her very favorite streaming TV show, Contest of Crowns. It's safe to say she spent quite a bit of time on the couch.

Seventy-two hours after hospital discharge, she developed severe recurrent dyspnea that wasn't resolving with home nebulizer treatments, and so she brought herself to the emergency department where she was noted to be profoundly hypoxemic, requiring a non-rebreather mask. A contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) was performed to evaluate for pulmonary embolism (PE), which was the primary concern in the emergency department.

Slide 3

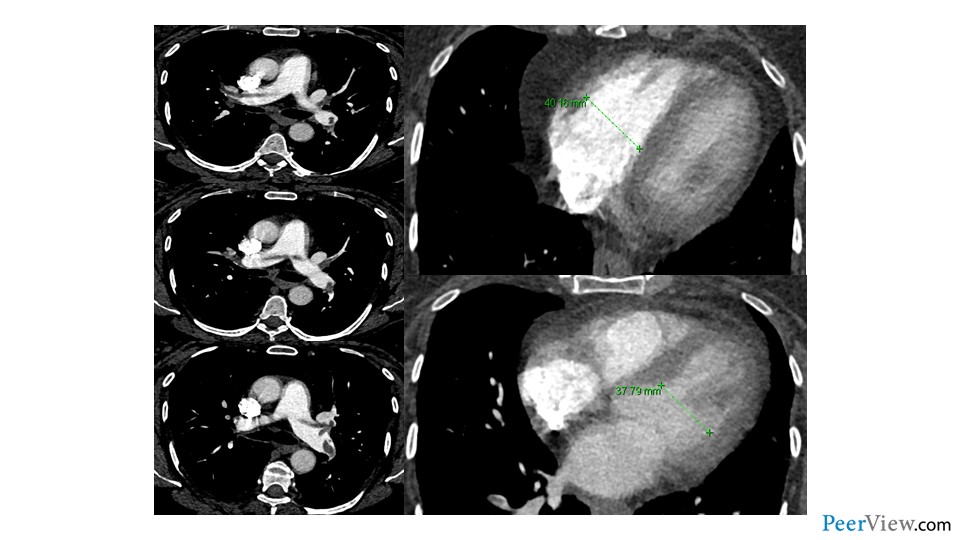

And here we can see the results of that chest CT. We see a large PE straddling the main bifurcation of the pulmonary arteries. This is what we would call a saddle PE. We see that that PE extends into the right and left main pulmonary arteries. And then on top of that, on the very same CT scan, we see that her right ventricle is actually enlarged, speaking to the fact that she has some right ventricular strain. And so, this case very nicely illustrates the danger of VTE following hospitalization, and the particular vulnerability that patients have as they transition across the continuum of care to home.

Slide 4

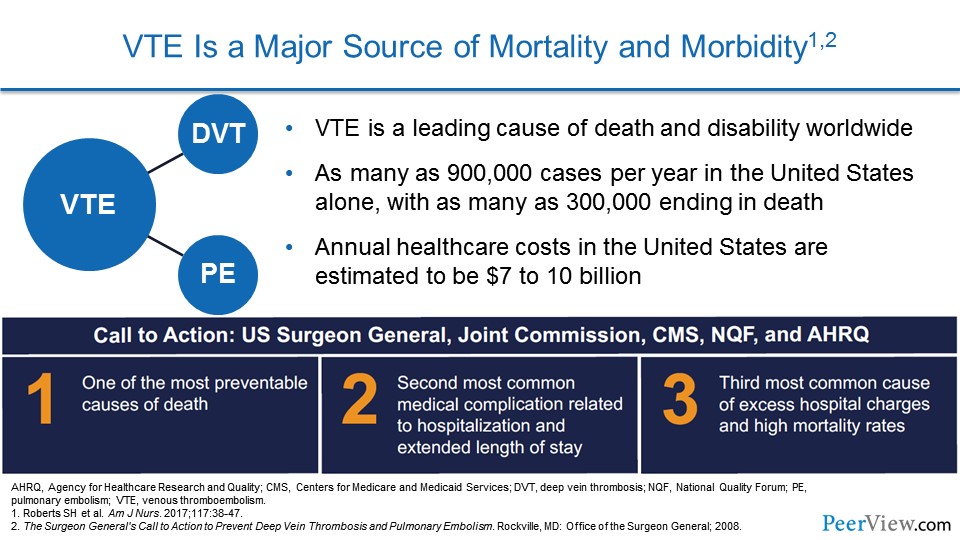

We're going to use this case to actually start talking about primary prevention and identifying patients at high risk for VTE. VTE is a major source of mortality and morbidity. We know that VTE is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. As many as 900,000 cases per year in the United States alone occur, with as many as 300,000 ending in death.

The annual healthcare costs in the United States are very high and estimated to be about $7 to $10 billion annually. In 2008, the US Surgeon General actually published a call to action to prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and PE, citing PE as one of the most preventable causes of death in hospitalized patients. PE is the second most common medical complication related to hospitalization and extended length of stay, and the third most common cause of excess hospital charges and high mortality rates.

Slide 5

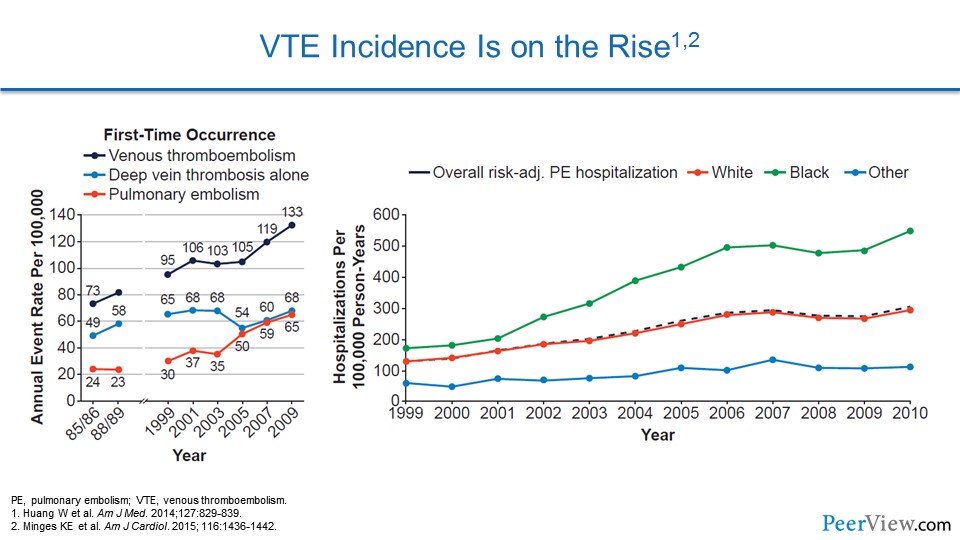

Epidemiologically, we can look at cohort studies to get an understanding of how VTE is on the rise. We see that in one study that comes from Worcester, Massachusetts—an area west of Boston where they have a large VTE study—that the rate of VTE has been increasing, and that's largely due to an increase in PE. Data from the Medicare Cohort actually shows that VTE is on the rise, and hospitalization for PE is increasing across a number of demographics.

Slide 6

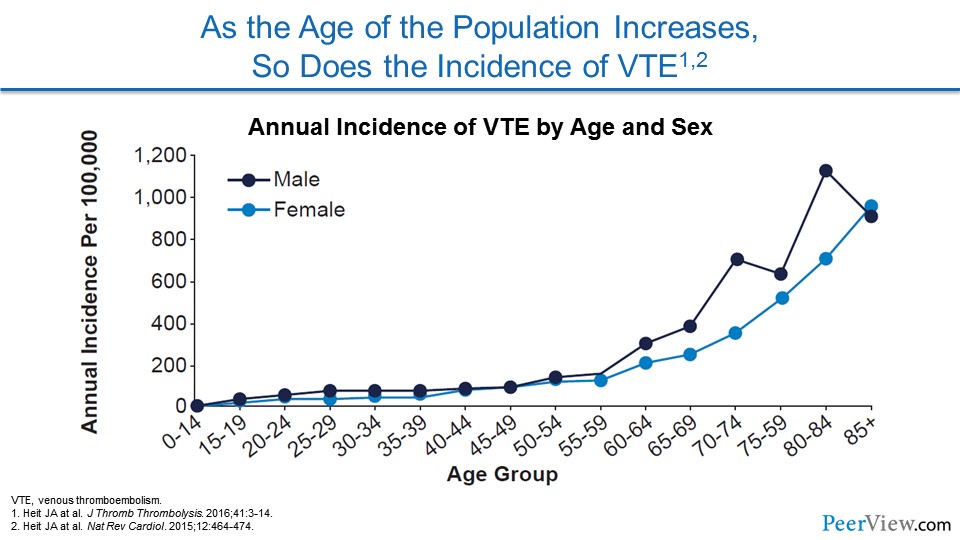

One of the issues is that our patient population is getting older and older. As our therapies for a number of chronic illnesses continue to extend life, we're seeing older and older patients being hospitalized. And we know that the risk of VTE for both men and women increases with age, so it's not really a wonder why we're seeing so much VTE in medical patients.

Slide 7

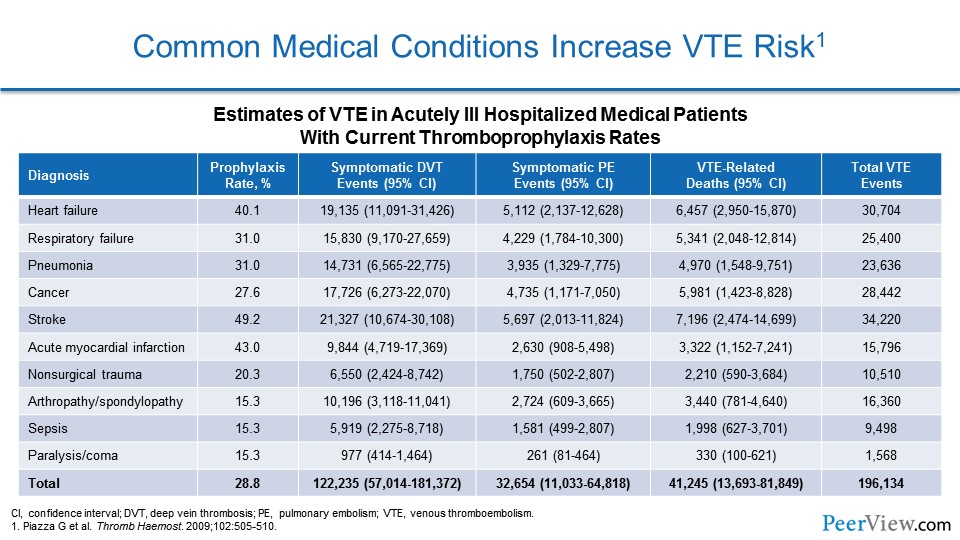

We know that common medical conditions actually increase the risk of VTE. Very common disorders that we admit to the hospital every day—heart failure, respiratory failure, infections like pneumonia or sepsis, malignancy, stroke, myocardial infarction—these all increase the risk of VTE, both DVT, PE, and even VTE-related death.

Slide 8

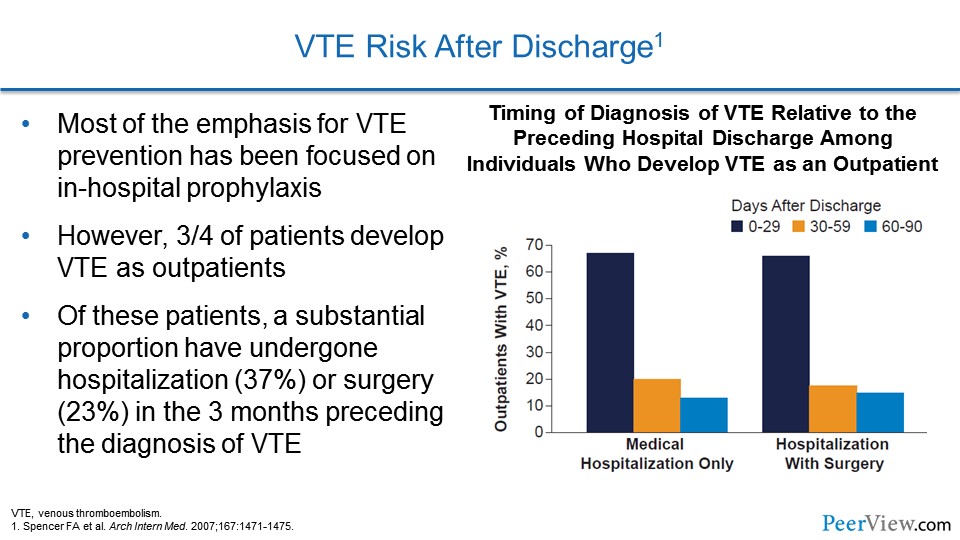

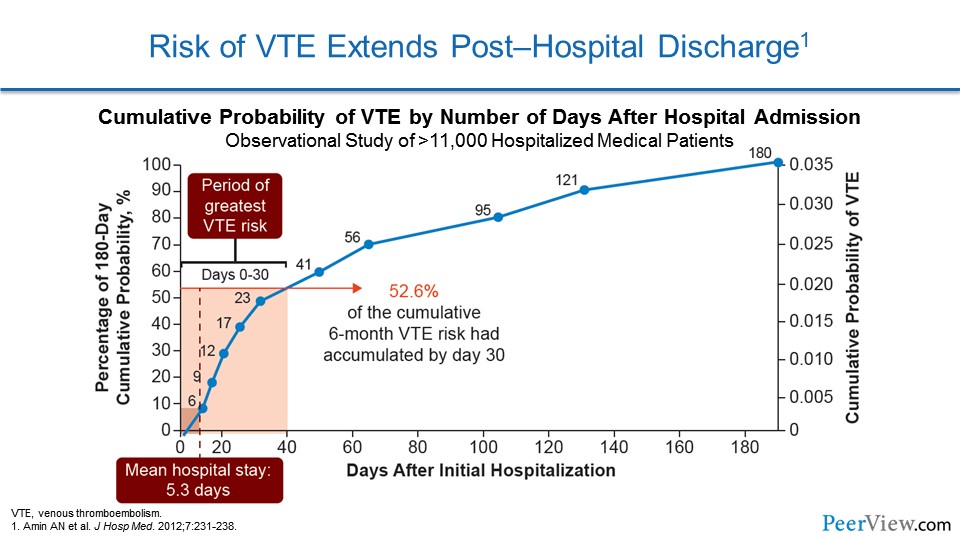

One of the more recent realizations about VTE risk is that most patients actually suffer VTE when they are at home following a hospitalization. We've spent a great deal of emphasis on trying to prevent VTE when patients are in the hospital, but these data, again coming out of the Worcester VTE study, actually show that three-quarters of patients actually develop VTE at home, with only a quarter suffering from it, while they're in the hospital.

Of these patients, a substantial proportion has undergone hospitalization or surgery in the 3 months preceding the diagnosis of VTE. If we look at the graph, we see that the risk of developing VTE in the outpatient realm is highest for the first month after discharge from the hospital for medical and surgical patients, but there still is some risk that persists in the second and third months.

Slide 9

This is another way of looking at similar data. Here we're seeing the cumulative probability of a patient developing VTE. Now, the mean hospital stay for most patients in the United States is somewhere between 4 and 5 days, and we can see here that the cumulative risk of developing VTE at the fifth day is actually relatively small. But as we extend and follow the patient out to 180 days after hospitalization, we see that the cumulative risk of developing VTE is incredibly large, and that that hospital stay is actually just the tip of a very big iceberg.

Slide 10

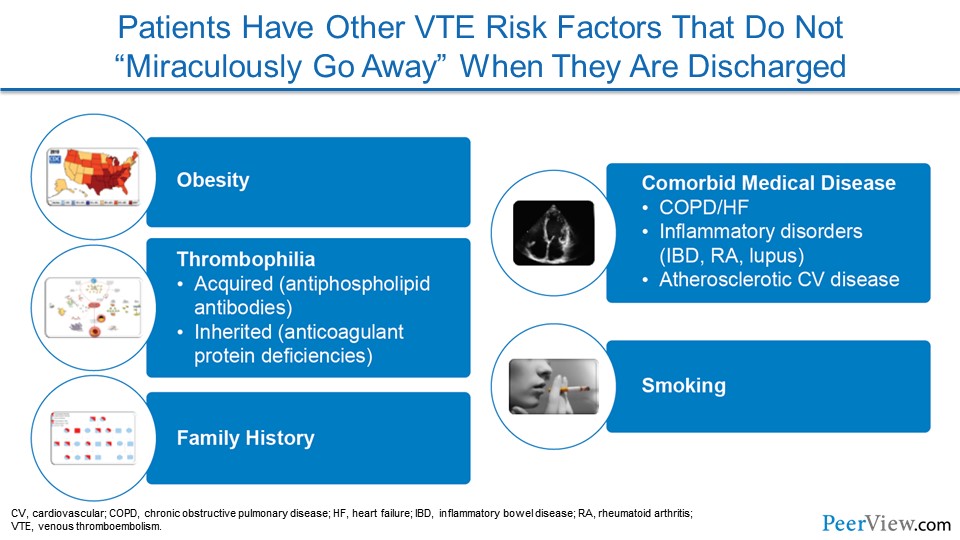

One of the hardest realizations for us to admit is the fact that patients have a lot of risk factors that lead to VTE that don't just go away when patients are discharged from the hospital. Unfortunately, we live in a country where obesity is an epidemic and our obese patients who are hospitalized go home and continue to be obese.

Many comorbid medical diseases, like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure, inflammatory diseases, like inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis, and then atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease land our patients in the hospital and also continue once they leave the hospital to home or the extended-care setting.

With so much pressure to get patients out of the hospital, we're sending patients home to continue to do some of the healing on their own with appropriate medical therapy, and so some of our patients aren't quite over their heart failure or quite recovered from their pneumonia, and so they carry some risk when they go home.

Some patients who we care for have underlying tendencies to develop thrombosis, like VTE, and that doesn't just go away when they leave the hospital. I would love to tell you that our patients who smoke and are admitted to the hospital go home and quit, but we all know that that's probably only a small fraction of patients.

And finally, family history is part of our preprogrammed genetics, and our patients who have a family history of VTE will go home with that same family history.

Slide 11

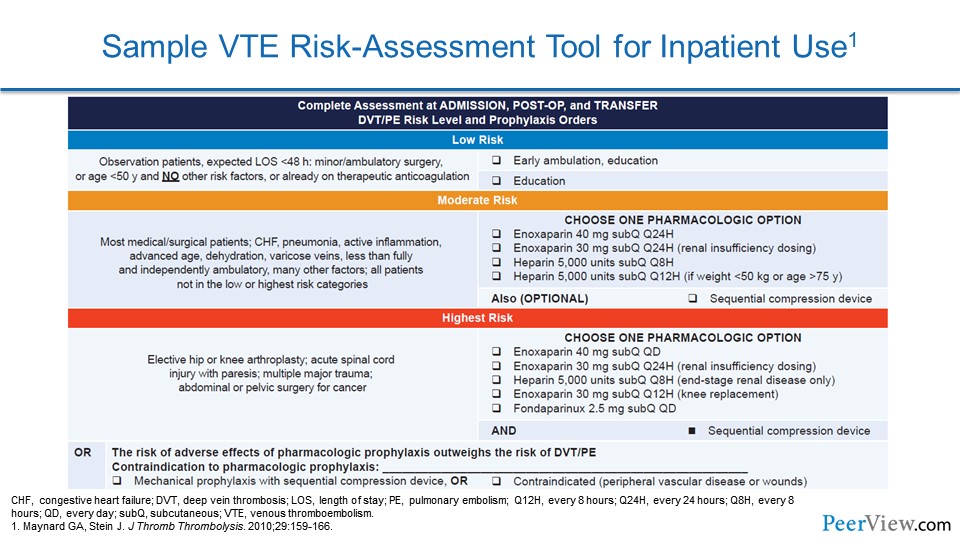

So how do we as providers identify patients who are in the hospital and are making their way home who may be at risk for VTE as they cross this continuum of care? Well, one way is to use VTE risk-assessment tools. Here's one example of a tool that was implemented in the hospitalized setting that categorized patients into different risk classifications. There were low-risk patients, moderate-risk patients, and high-risk patients; and these risk stratifications took into account different comorbidities that impact the chance that a patient might develop DVT or PE. Then, based on what risk category the patient's in, you would make a decision about what sort of preventive measures should be taken.

Slide 12

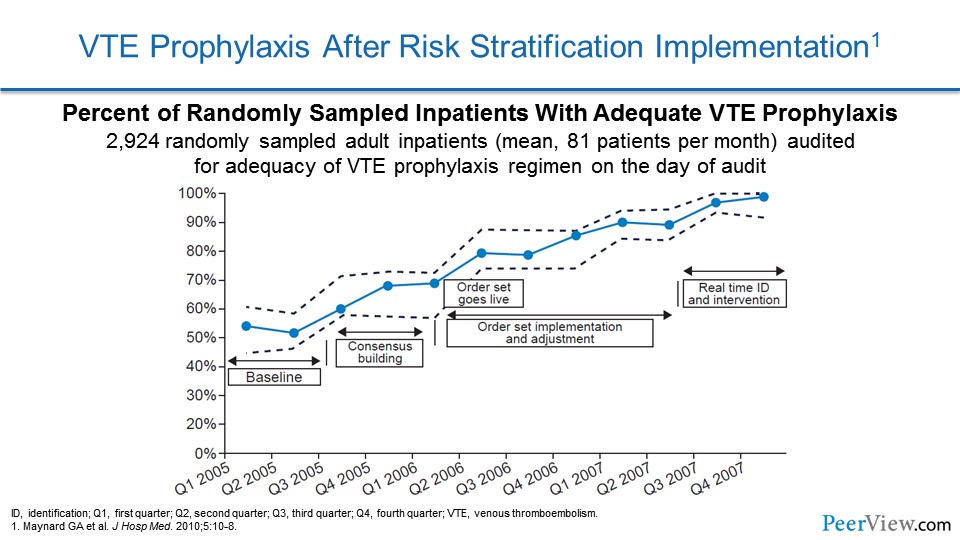

Here we see the results of implementing such a strategy. The investigators who implemented that very same risk stratification tool that I showed you demonstrated a low rate of VTE prophylaxis when they started the program. And then, as they implemented it and made incremental changes to it to improve it, you can see, over time they actually almost got to 100% VTE prophylaxis in the patients who needed that protection. And so, this is really a marvelous way of protecting our patients in the hospital and should be able to be translated into the outpatient realm.

Slide 13

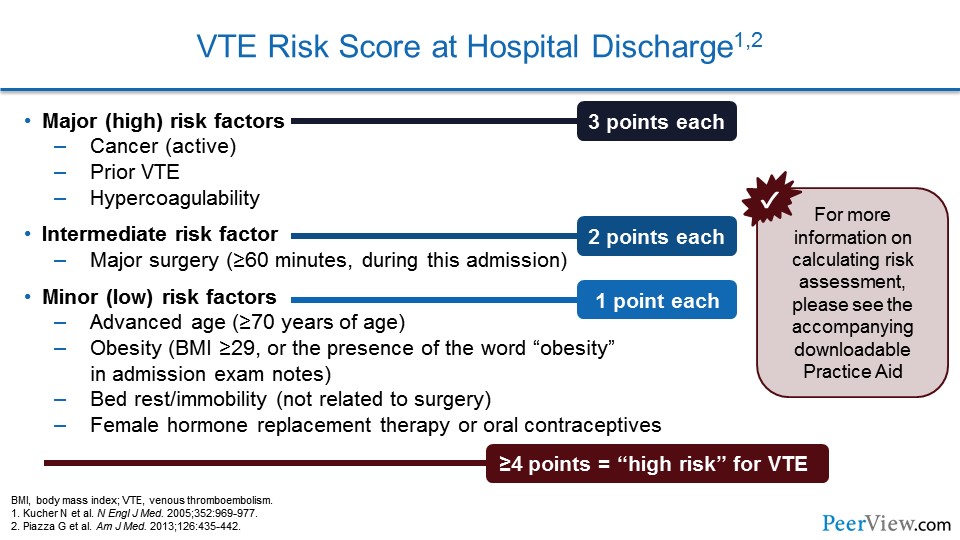

Other centers have used VTE risk scores that the computer system can calculate. This was one that we used in a study to prevent VTE using our electronic health record. And this categorized patients according to their risk factors. So major (high) risk factors got three points and included cancer, prior VTE, or hypercoagulability.

An intermediate risk factor included major surgery; that got the patient two points. And then one point was assigned for patients who had the following minor risk factors: advanced age, obesity, bedrest or immobility, or the use of female hormone replacement therapy or oral contraceptives. When we calculated all of the points, patients who had four points or higher were calculated to be high risk for VTE and should get prophylaxis.

Slide 14

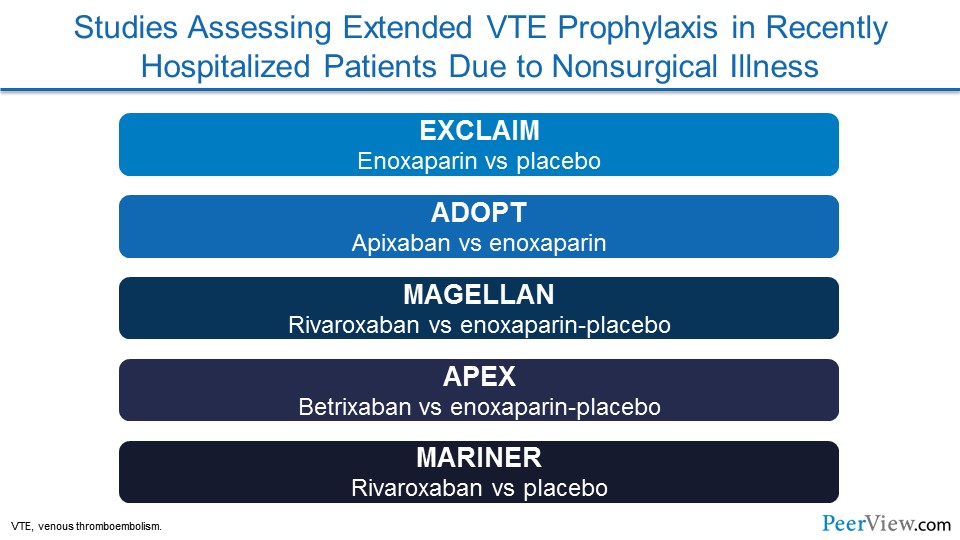

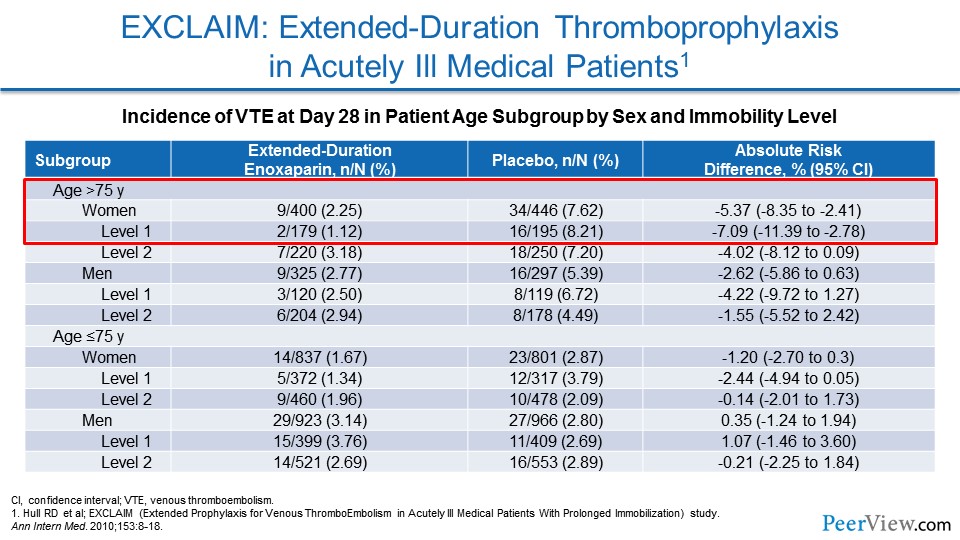

Now, there have been a number of studies that have actually looked at preventing VTE in patients as they cross this continuum from the hospitalized setting into the extended-care or home setting. Some of these studies include: EXCLAIM, which was a trial that compared an injectable blood thinner called enoxaparin with placebo; ADOPT, which looked at one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) called apixaban versus enoxaparin; MAGELLAN looked at a different DOAC, rivaroxaban, versus enoxaparin and then placebo; APEX was a more recent trial that looked at a different DOAC, the latest one to be FDA approved, betrixaban, and compared that with enoxaparin and placebo; and then most recently was the MARINER trial, which once again looked at rivaroxaban versus placebo. And we're going to talk a little bit about each of these trials.

Slide 15

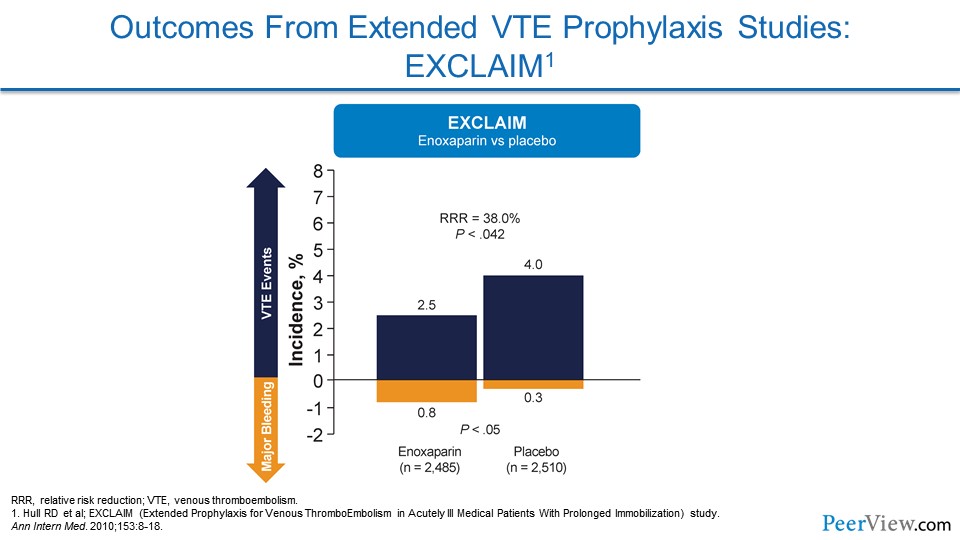

If we look at EXCLAIM—and we see the benefit is on the top half and the potential harm of extended therapies is in the bottom part of these graphs—you see that VTE events were reduced in patients in EXCLAIM who were getting extended enoxaparin. The problem was there was an increased risk of bleeding events.

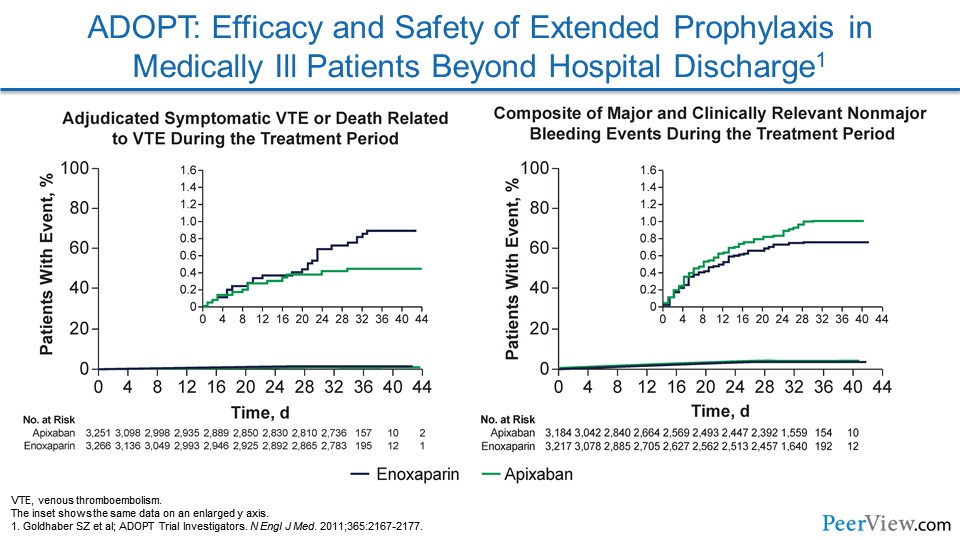

Slide 16

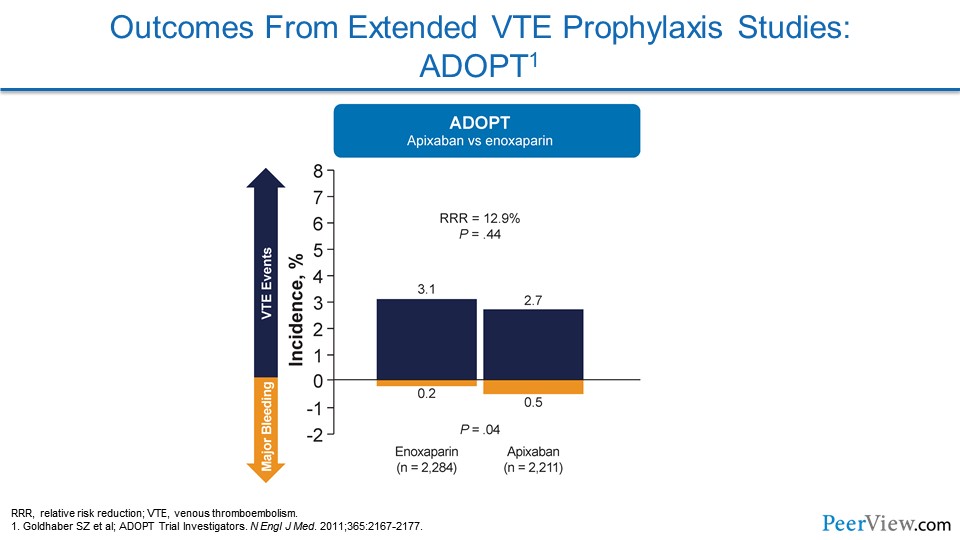

In ADOPT (this was the study of apixaban), there really wasn't a significant reduction in VTE events, and there was an increase in bleeding, so there was no overall net clinical benefit to providing apixaban in an extended fashion.

Slide 17

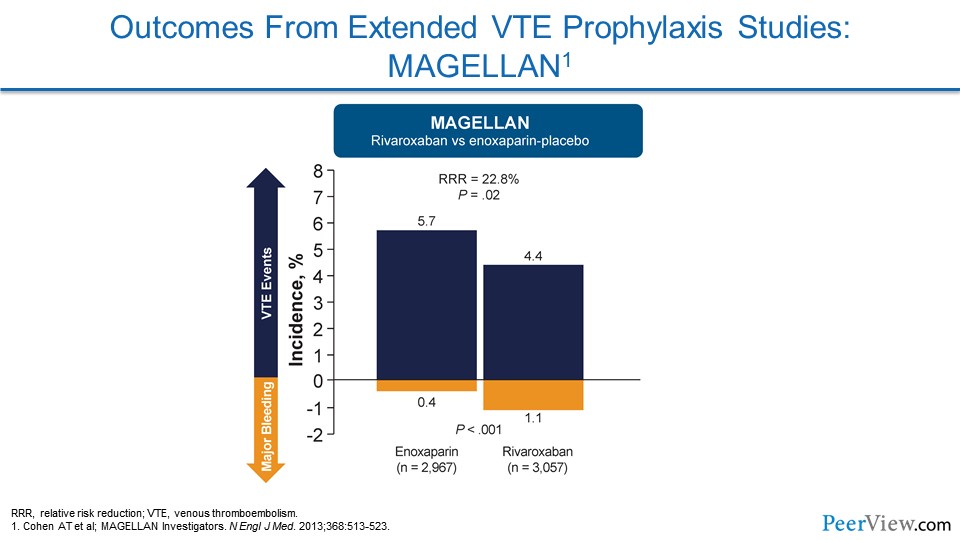

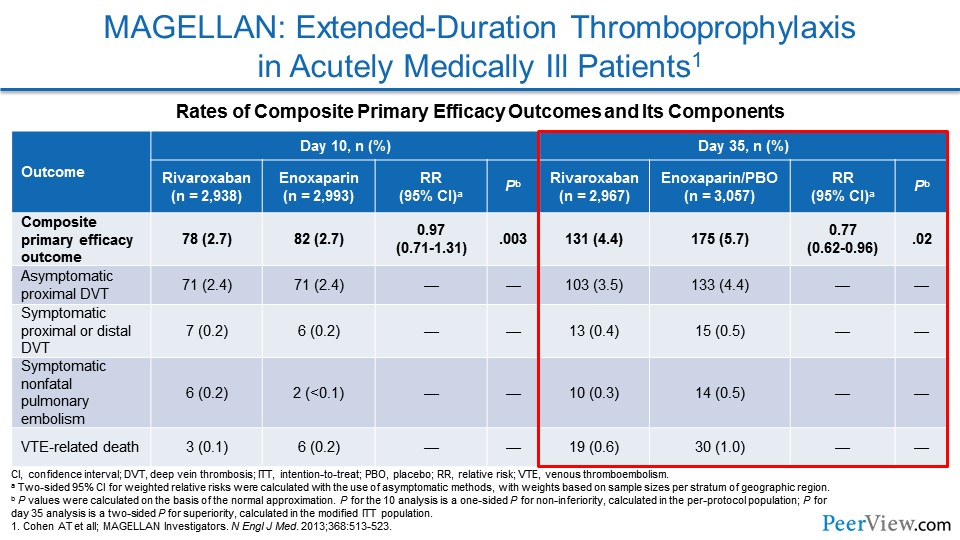

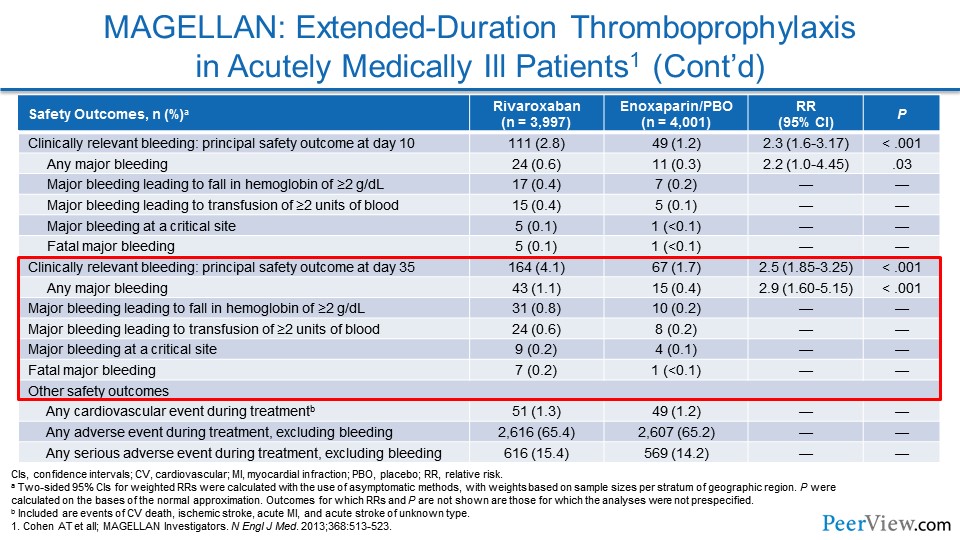

MAGELLAN evaluated rivaroxaban, and they were able to show a reduction in VTE events, but that came at the cost of an increased risk of bleeding events. So when you do the math for a net clinical benefit, it didn't really show that benefits to patients were seen.

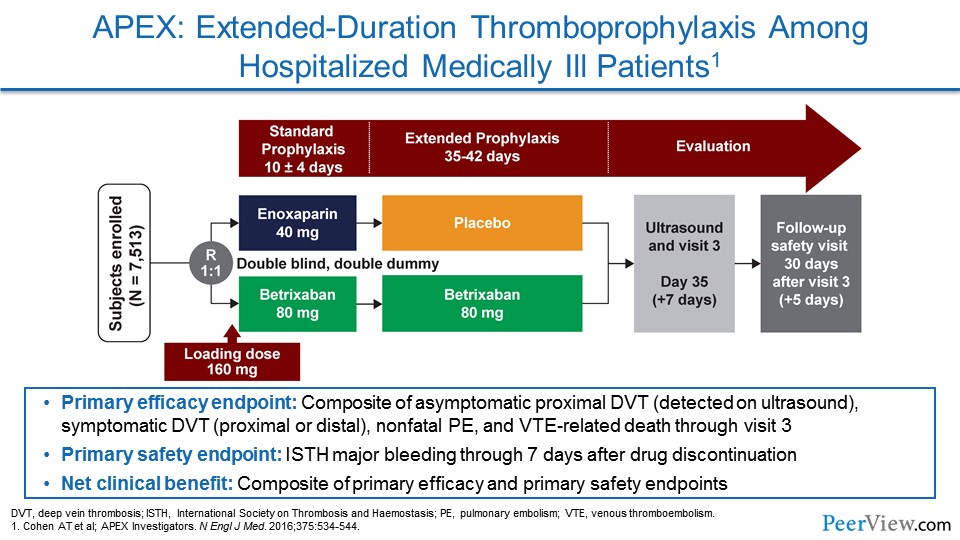

Slide 18

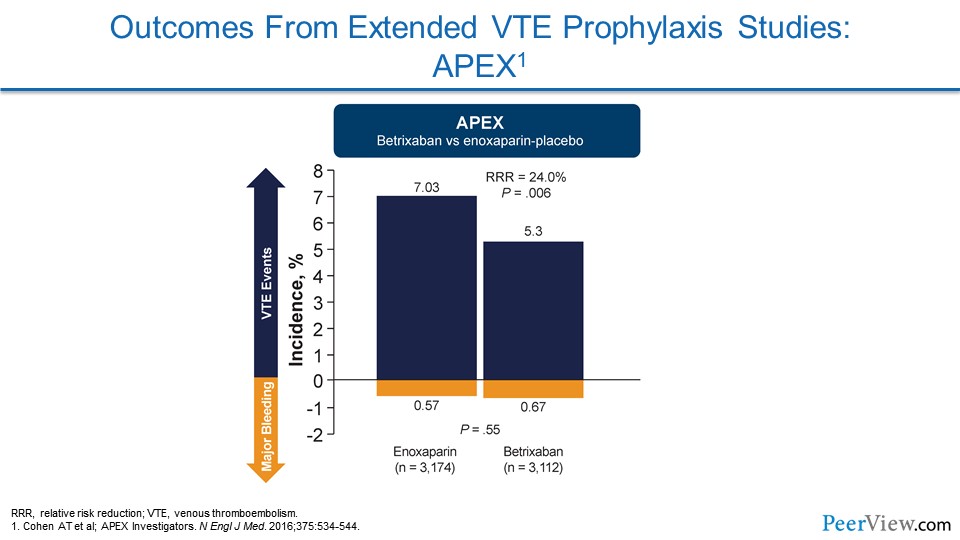

APEX looked at betrixaban. And here's one of the first studies that actually showed what we would hope to see from these trials: a reduction in VTE without any increase in the risk of bleeding. And so the net clinical benefit goes to the patient for reducing VTE.

Slide 19

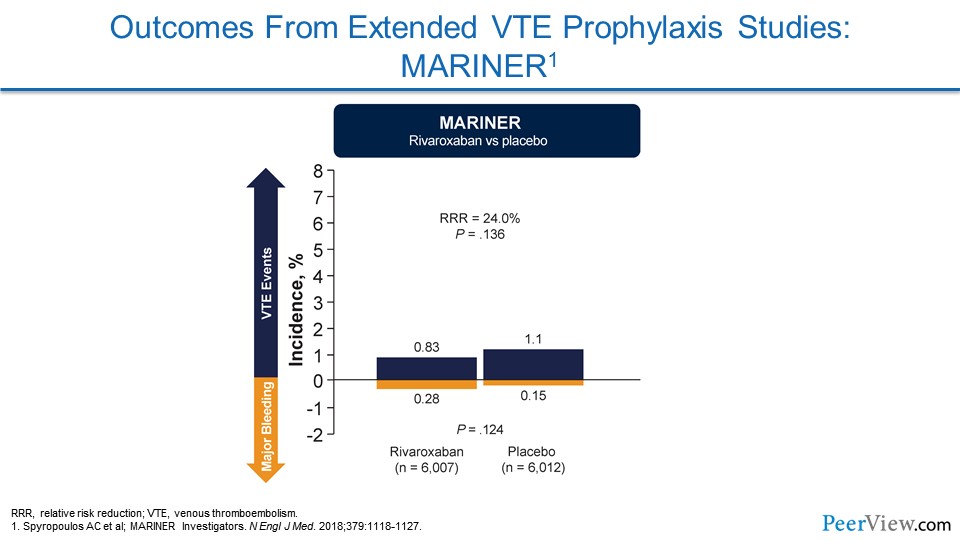

MARINER was the most recent of these trials. It wasn't able to show a significant reduction in its overall endpoint, but as I'm going to show you, they were able to prevent VTE and there didn't seem to be an increased risk of major bleeding.

Slide 20

So now we're going to dive into these individual trials a bit more. With EXCLAIM, as I mentioned, this is the study that focused on extended-duration enoxaparin versus placebo for patients at increased risk of VTE. And, unfortunately, with this trial, unless you were an elderly woman who was very much immobilized, you did not get a net clinical benefit, and so the overall trial was negative.

Slide 21

ADOPT looked at apixaban. There wasn't a significant reduction in VTEs, and there was an increase in major bleeding.

Slide 22

MAGELLAN was one of these studies that looked at a DOAC for preventing VTE in an extended fashion. And, here (Slide 22), we were actually able to see a reduction in the composite primary efficacy outcome of VTE.

Slide 23

The problem was there was an increase in bleeding endpoints—in particular, clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. And that actually made it so that there wasn't a net clinical benefit overall.

Slide 24

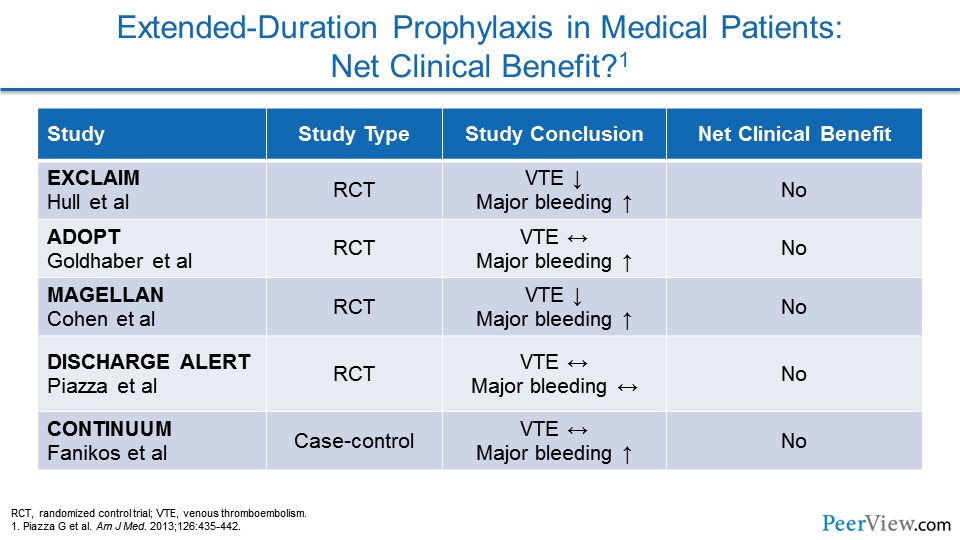

When we look at these early trials in aggregate, what we see is that many of them had a decrease in VTE but an increase in major bleeding, or didn't really impact either endpoint. And so the net clinical benefit for all of these trials was actually null.

Slide 25

APEX was a different trial focused on a different DOAC called betrixaban. Patients in this study were randomized to either get enoxaparin for a set period of time and then a placebo, or betrixaban for the set period of time and then they would extend out to 42 days with oral betrixaban. And this was a blinded study, so patients got placebo injections and placebo pills.

Slide 26

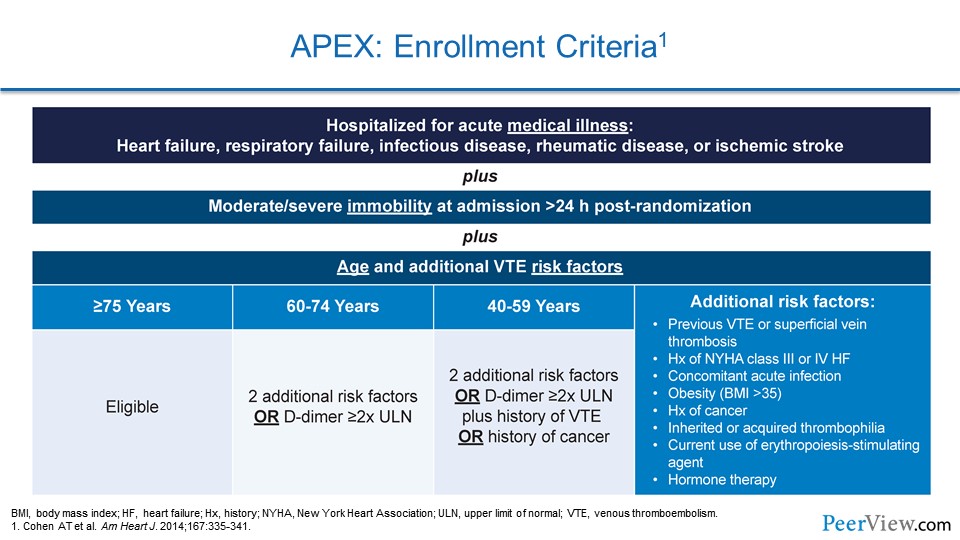

The entry criteria were actually quite interesting. What the investigators tried to do with APEX was to hone in on the much-higher-risk medical patient population, ones who were going to stand to benefit. So they enrolled a large number of advanced elderly patients. They enrolled patients with a high number of comorbidities that increase the risk of VTE.

Slide 27

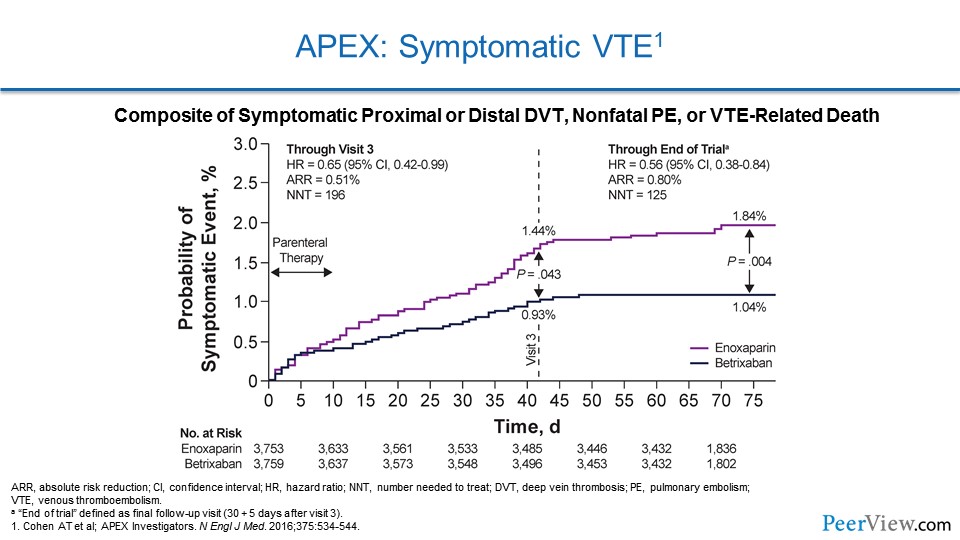

And what we can see is there is a significant reduction in symptomatic VTE when patients continued betrixaban, but it gets even more interesting than that. The study drug actually stops at around 42 days, and if we look at this graph and hone in at 42 days, that's when patients came off study drug. And if we look, even after the patients in the betrixaban arm stopped the study drug, they continued to be protected from VTE. And this is actually a very rare observation in clinical trials called the "legacy effect," where patients continue to have a benefit long after they stopped the drug. And we don't see this often, and that was a very special thing about this study.

Slide 28

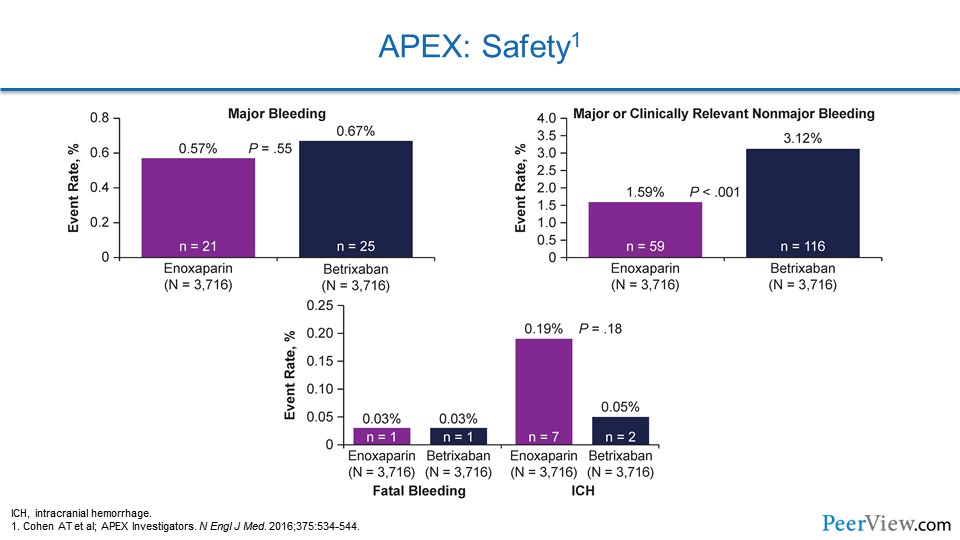

Now, when we look at safety, there wasn't an increased risk of major bleeding with this very potent prophylactic measure. There was an increase in clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, but there wasn't any increase in intracranial hemorrhage. If anything, there might've been a reduction in intracranial hemorrhage, at least numerically.

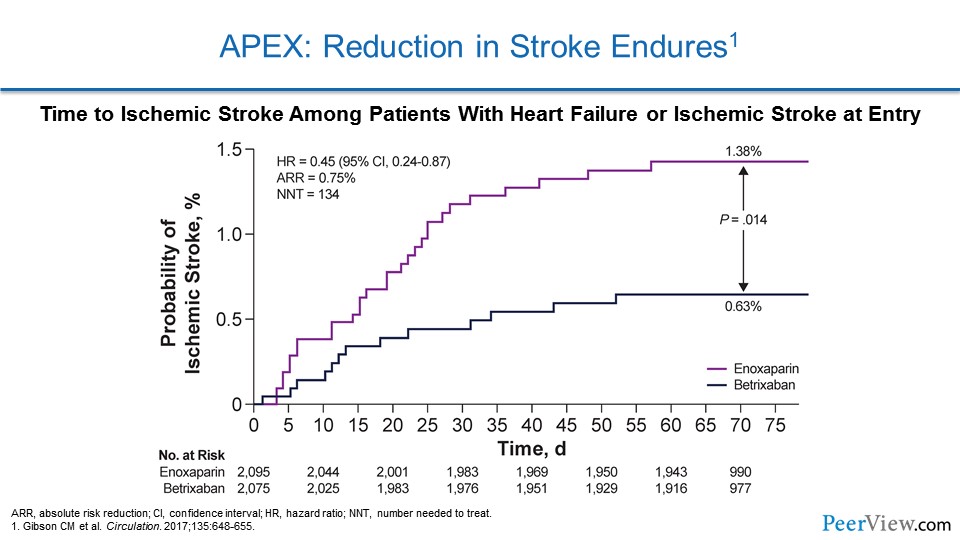

Slide 29

They did a substudy that looked at the risk of stroke in these patients, and, once again, patients receiving betrixaban had a marked reduction in ischemic stroke. But on top of that, even after they stopped the study drug at 42 days, they continued to be protected from stroke. So once again, a very strong legacy effect here.

Slide 30

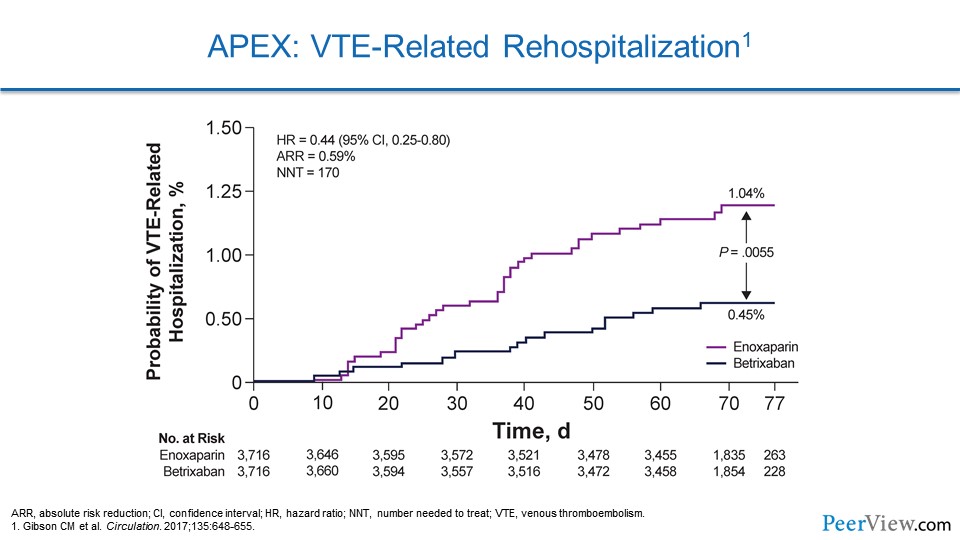

If we look at VTE-related hospitalization in APEX, again the betrixaban group had a marked reduction in the risk of having to be rehospitalized due to VTE. And again, even after they stopped their drug at 42 days, they were protected in a legacy effect.

Slide 31

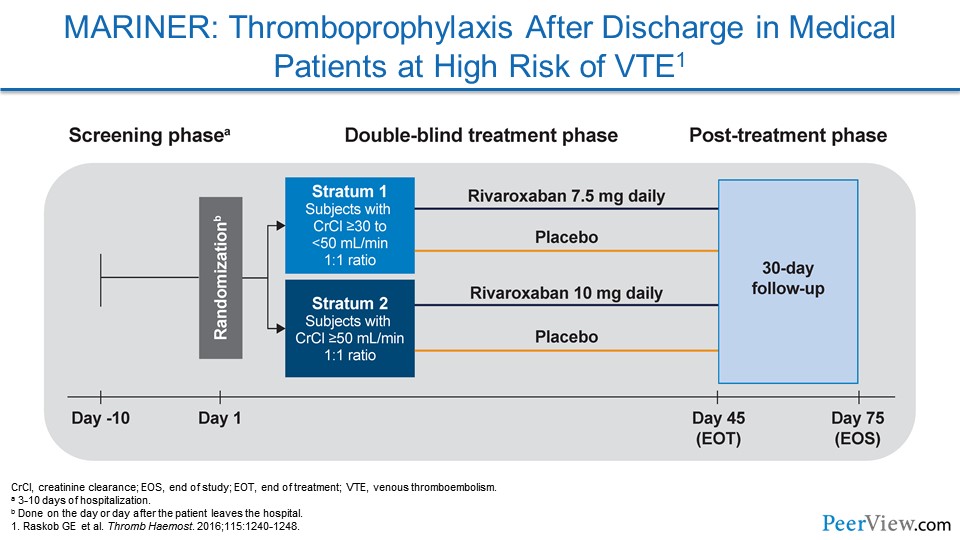

Now, MARINER was the most recent of these thromboprophylactic trials for medically ill patients at high risk for VTE. This study focused on rivaroxaban. In a way, it's similar to MAGELLAN, but, in this study, they looked at two different doses of rivaroxaban.

Slide 32

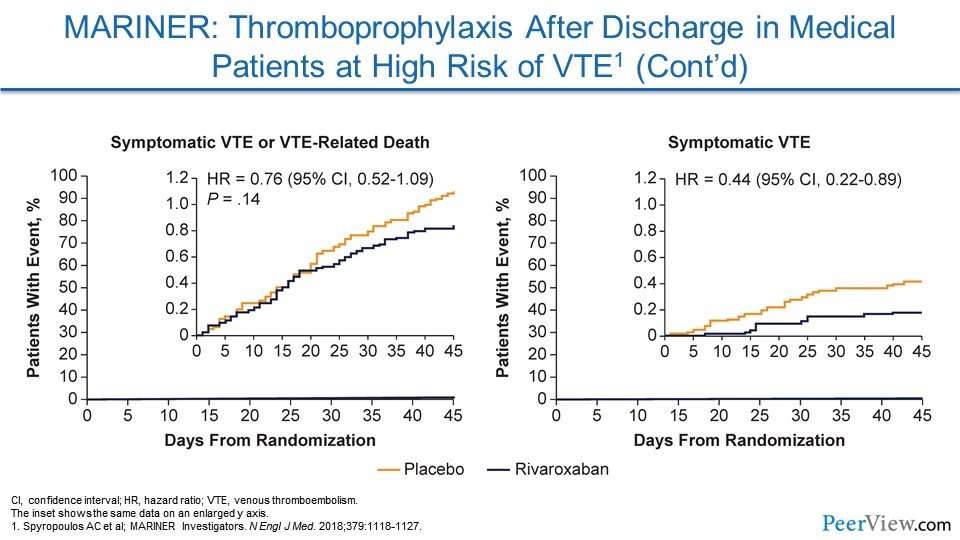

They were not able to show a significant reduction in their composite endpoint of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death. But if we look a little bit further at the data, we see that they showed a very nice reduction in symptomatic VTE.

Slide 33

For more expert commentary regarding the results and impact of these and other trials, please visit: "Clinician News and Research" via the North American Thrombosis Forum at https://natfonline.org/clinicians.

Recognizing Patients at Risk for Recurrence and Strategies for Extended Secondary Prevention

Slide 34

Now we're going to transition to a different part of prevention, and this is focusing on recognizing patients at risk for recurrence after they've had a VTE event, and strategies for extended secondary prevention.

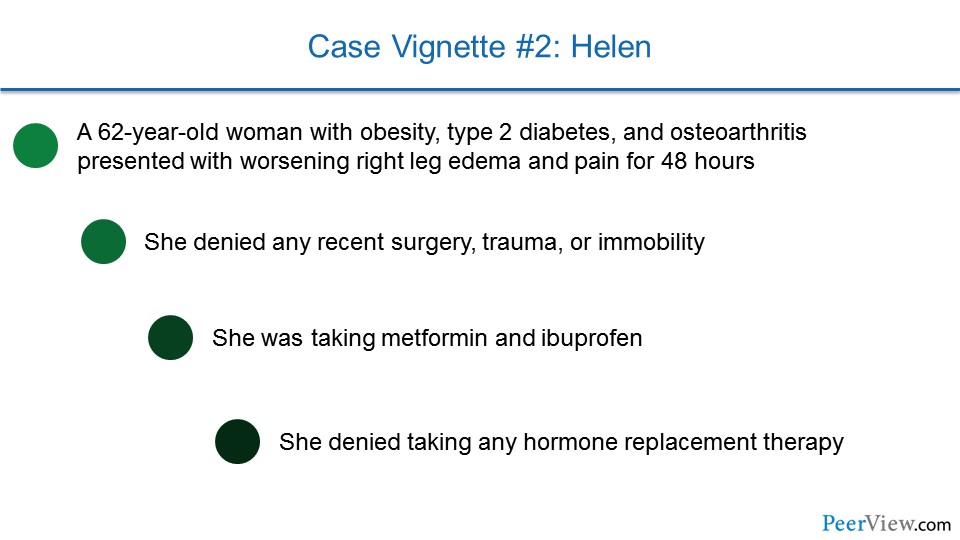

So of course, we have another case, and this is Helen. She's a 62-year-old woman with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and osteoarthritis, who is coming in with worsening right leg edema and pain for 48 hours. She hasn't had any recent surgery, trauma, or immobility, and she's taking metformin and ibuprofen. She's not taking any hormone replacement therapy.

Slide 35

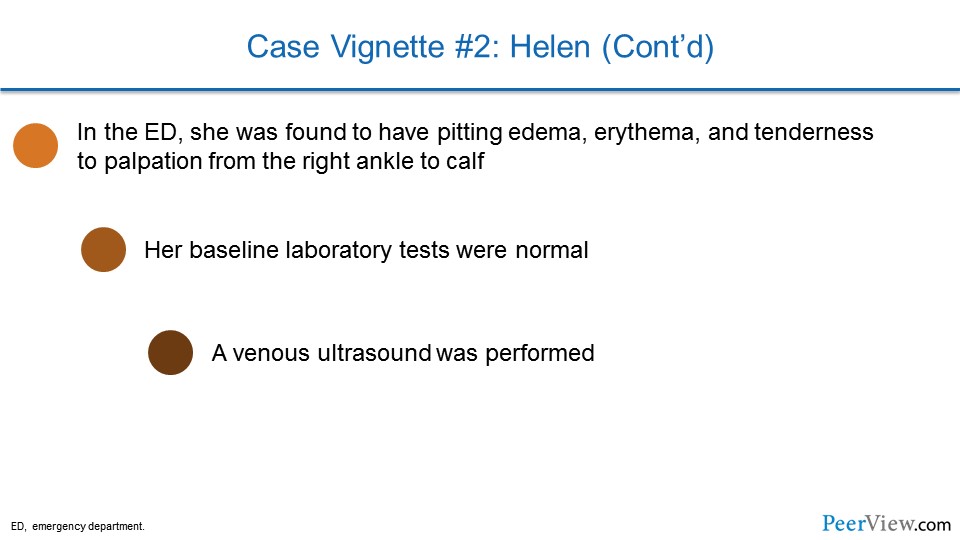

In the emergency department, she's found to have pitting edema, some erythema, and some tenderness to palpation from the right ankle to calf. Her baseline laboratory tests look fine, and so a venous ultrasound is performed.

Slide 36

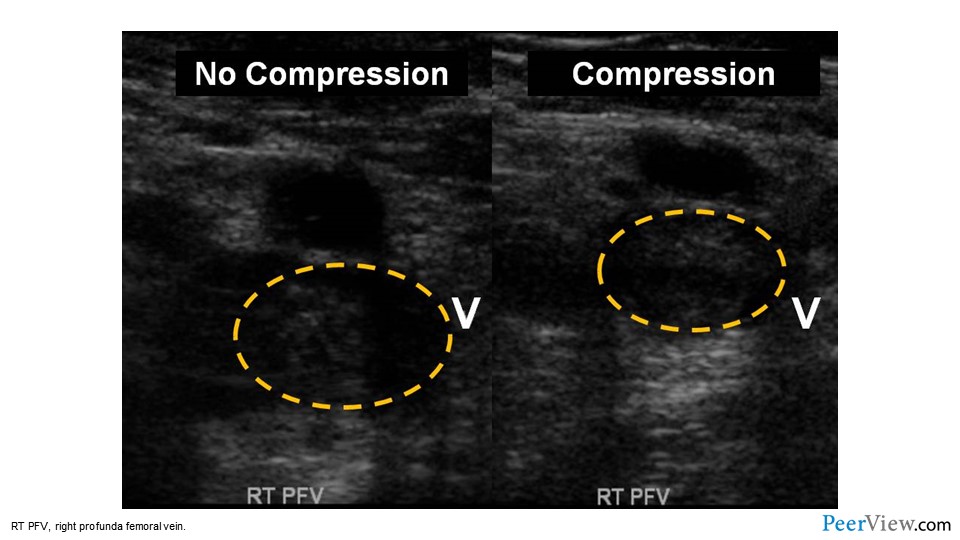

And here we see the results of that ultrasound. Without compression, the ultrasound transducer is just put right above the vein of interest, and we see that the vein is highlighted in the yellow hatched line. With compression—when the ultrasound technician is pushing down with the transducer—we expect veins that are full of a liquid, blood, to compress completely. Here, the vein doesn't compress; there's still something inside that vein, and this is the gold standard for diagnosing DVT. And so this patient has suffered a right-sided femoral vein thrombosis.

Slide 37

She's started on a DOAC for an anticipated duration of 6 months. She returns in follow-up several months later and is unsure whether she should stop anticoagulation. So she, in her question to us about whether she should stop anticoagulation, is hinting at a concept of VTE as a chronic disease. When a patient asks you, "Am I still at risk for VTE when I stop anticoagulation?" they're asking you, "Is this a chronic process that doesn't go away?"

Slide 38

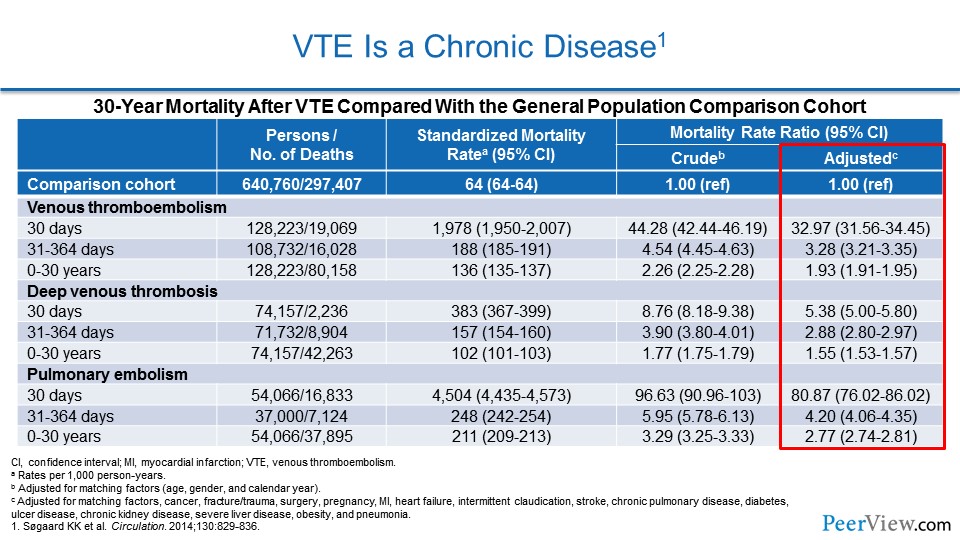

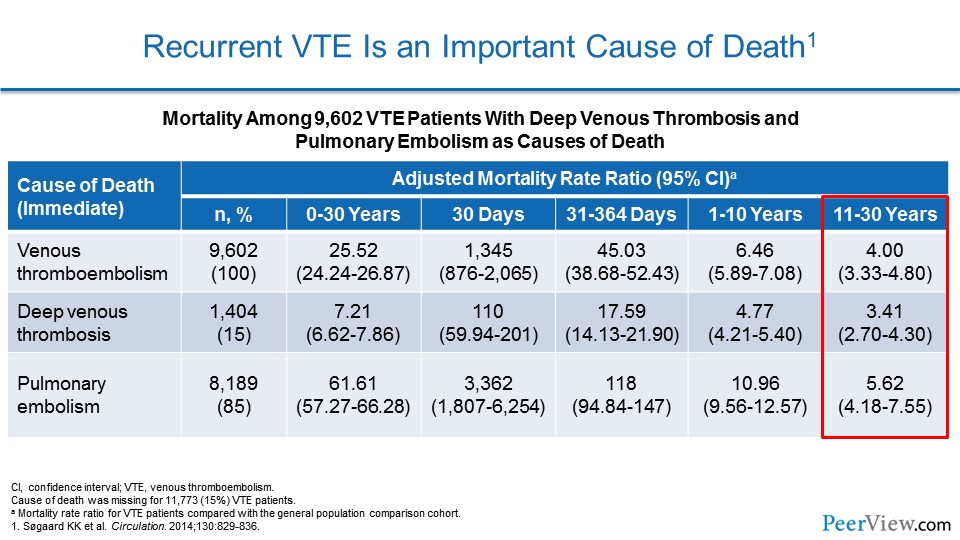

And we can turn to data from Denmark, where they have a large, health registry that essentially looks at every patient in the country and every interaction of that patient with the healthcare system. In this analysis, they looked at patients who had a first VTE event, and they looked at their mortality rate compared with patients who had never suffered a DVT or PE. And what they found was the mortality rate is higher and that increased mortality rate in patients who've had a VTE persists out to—not 1 year, not 10 years—but out to 30 years. And we can see that highlighted.

Slide 39

When we look at the phases of treatment for patients, we realize that patients here again go through a continuum. There is an acute phase where we're treating them with anticoagulants to help their body break up the thrombus. Then there's an intermediate phase, where we're trying to prevent them from having recurrent VTE. And then there's a chronic phase, a secondary prevention phase, where we're adjusting our anticoagulant regimen to try to make sure that they don't suffer increased risk of VTE out to 30 years, and that they don't suffer an increased risk of mortality.

Slide 40

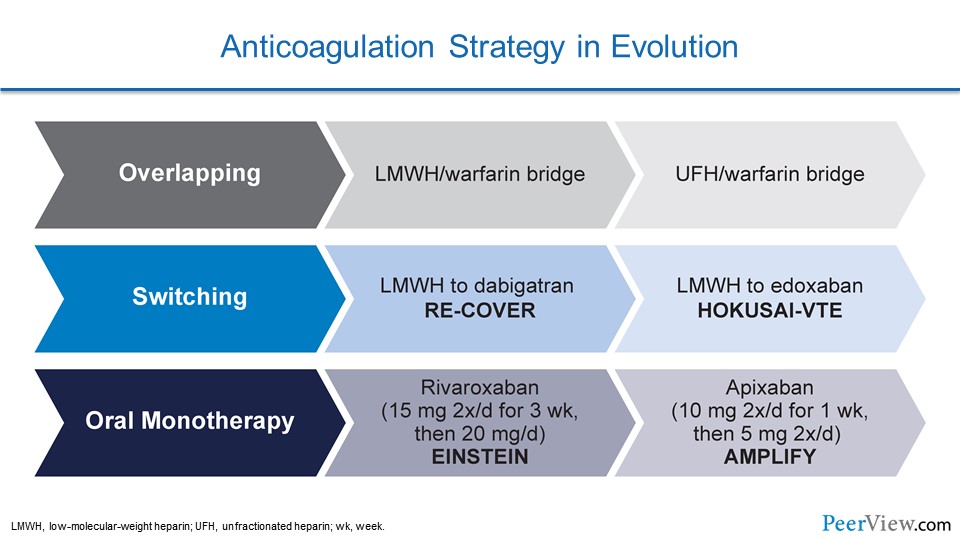

When we look at our anticoagulation strategies, we see that we've really gone through an evolution. For decades, we were very limited to one way of treating our patients with DVT and that was called overlapping or bridging. We gave patients low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin, and we bridged them over to warfarin.

With the arrival of the DOACs, we have two additional avenues for giving our patients blood thinners. We have switching, where we give our patients a LMWH or unfractionated heparin, and then transition them to either dabigatran or edoxaban. And then, we have direct oral monotherapy, where we don't have to give patients an IV with heparin, and we don't have to give them any injections; we give them a higher oral dose of either rivaroxaban or apixaban for a set period of time and then we switch them over to a maintenance dose. And this really facilitates anticoagulation. It helps us transition patients to home, and we may find in the future that it helps get some patients out of the emergency department without needing to be admitted.

Slide 41

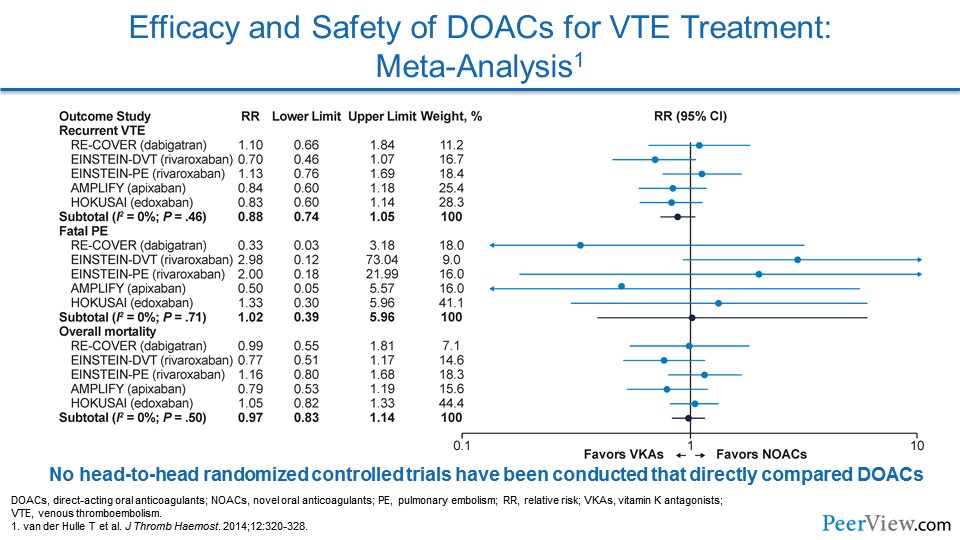

When we look overall at the impact that the DOACs have had in VTE, we see that for efficacy—for preventing recurrent VTE—they're very comparable with warfarin.

Slide 42

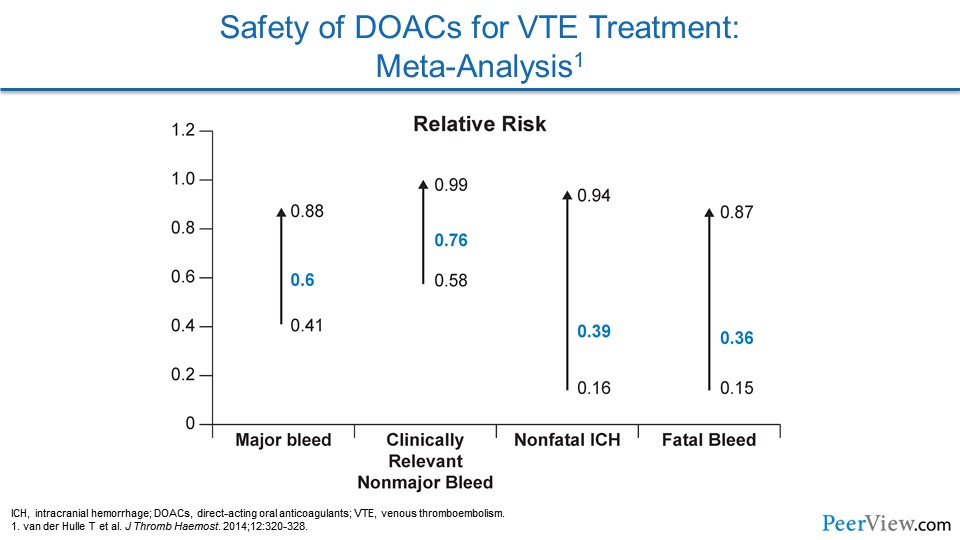

But where they really shine is in safety. All of the DOACs reduce the risk of major bleeding compared with warfarin. They reduce the risk of clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, they reduce the risk of nonfatal intracranial hemorrhage, and they prevent fatal bleeding compared with warfarin.

Slide 43

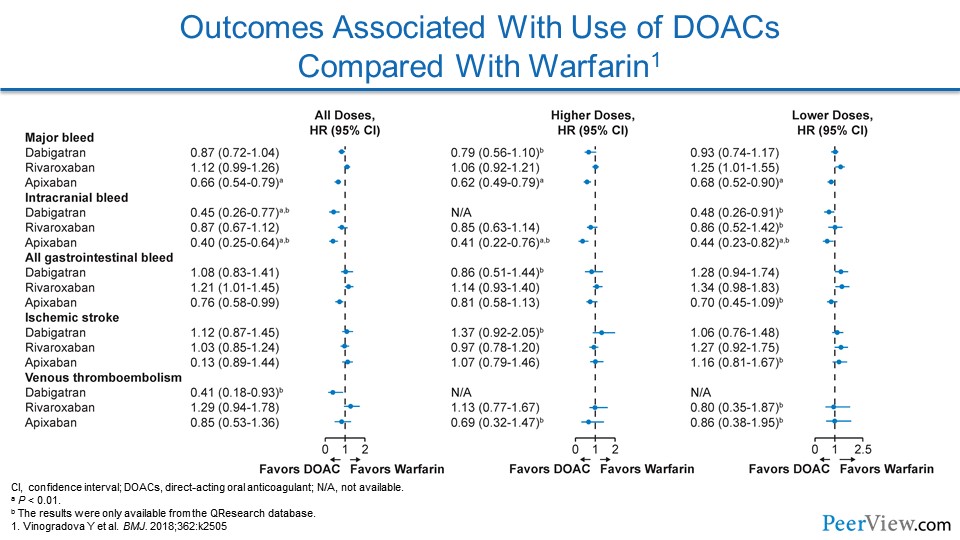

When we look at outcomes associated with the use of DOACs compared with warfarin, we see for almost every metric of bleeding, the DOACs seem to perform as good as, if not better than, warfarin. I'll caution you when looking at these types of studies, because none of the DOACs were actually put into a randomized controlled trial where they were compared with each other. There is a hint that drugs like apixaban may have a lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, but again, there haven't been head-to-head comparisons between the DOACs.

Slide 44

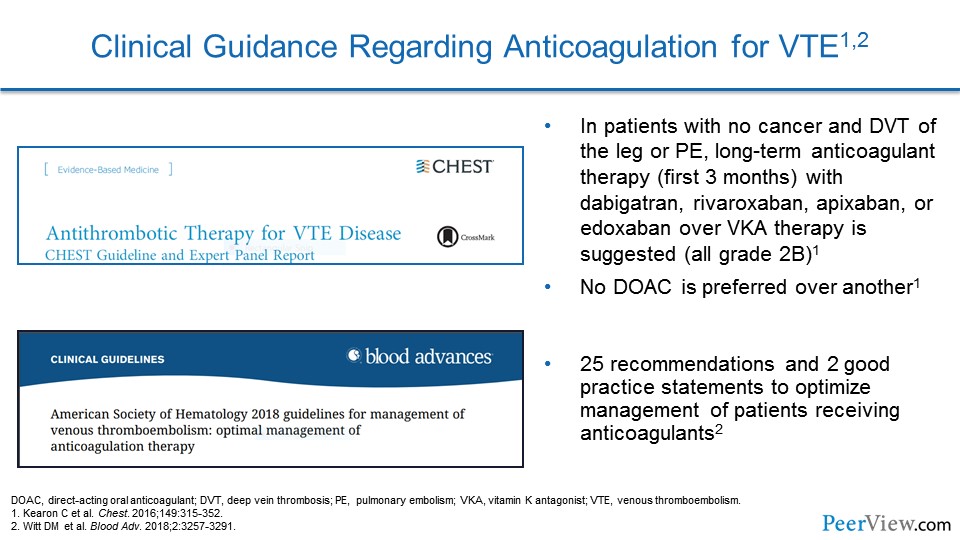

When we look at guideline documents for how we should anticoagulate patients with VTE, the 2016 American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines actually strongly recommend that we select a DOAC over a vitamin K antagonist like warfarin. They don't particularly favor one DOAC over another, but they do emphasize that a DOAC should be first line. We also have 2018 American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines that provide us also with recommendations.

Slide 45

Now, recurrent VTE is an important cause of death. I showed you these Danish health registry studies. These data showed that patients had an increased risk of mortality out to 30 years when they had a VTE event compared with patients who didn't have a DVT or PE. And an important cause of that increased mortality is actually recurrent PE.

Slide 46

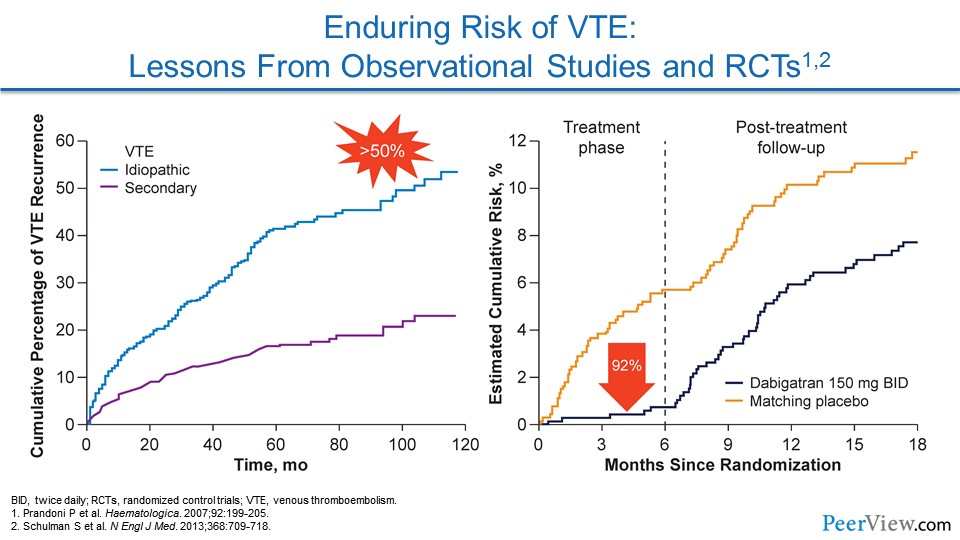

We know from other epidemiologic data that the risk of VTE recurrence is particularly high in patients who have idiopathic or unprovoked VTE. So these are patients where we can't pinpoint a cause of their VTE event. They didn't have surgery, they weren't immobilized, they hadn't had trauma. And these patients have in excess of 50% risk of having recurrent VTE at 10 years. I don't want to underemphasize the fact that patients who have a clear trigger to their VTE aren't completely out of the woods. They have a risk of recurrent VTE that approaches 25% over 10 years.

If we look at this other graph showing two lines, we see this is a study of dabigatran, one of the DOACs, compared with placebo. And this is looking at patients who've suffered unprovoked VTE. When the patients are during the treatment phase, if they're getting dabigatran compared with placebo, they have an incredible 92% reduction in the risk of recurrent VTE.

There's actually an even more important lesson from this graph. As soon as the study drug is stopped at 6 months, look at what happens to the rate of recurrent VTE. It immediately starts to track upwards, in parallel with the placebo group, showing that there is an underlying risk to recurrent VTE that the anticoagulant is preventing. And as soon as we stop it, that risk comes back.

Slide 47

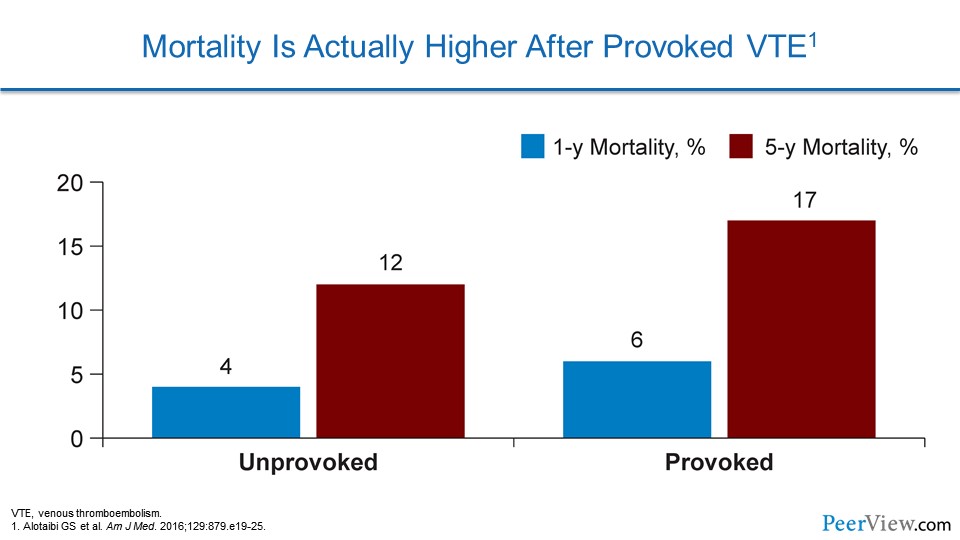

Mortality can actually be higher in some patients who have provoked VTE. In these data, we can see that there's a higher risk of 1-year and 5-year related mortality when patients have provoked VTE. That may be simply the fact that we don't typically extend therapy in these patients, and some of them may be unprotected from a life-threatening VTE event.

Slide 48

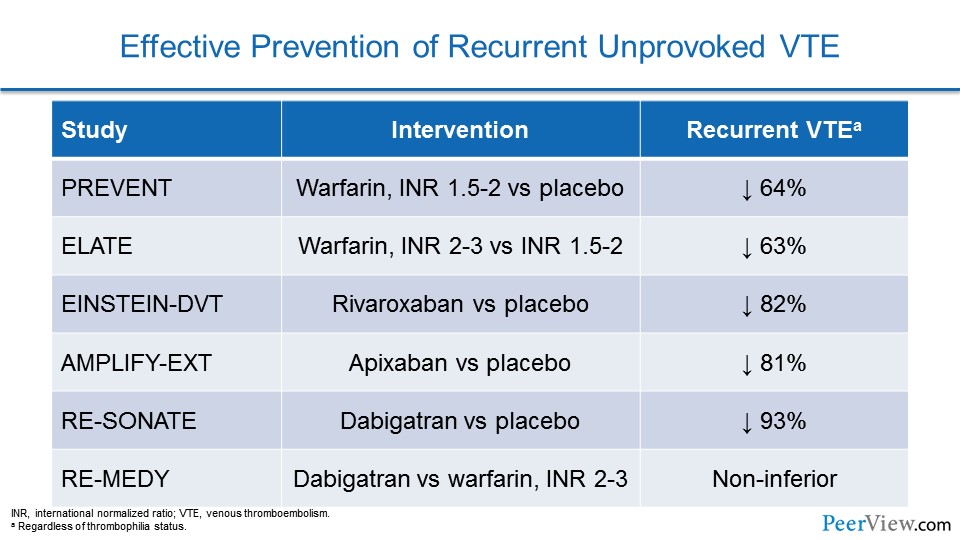

There is good news for our patients who have unprovoked VTE. Whether we use warfarin or a DOAC, if we extend out preventive therapy, we're going to provide our patients with a 60% to 90%, and perhaps even higher, relative risk reduction in recurrent VTE.

Slide 49

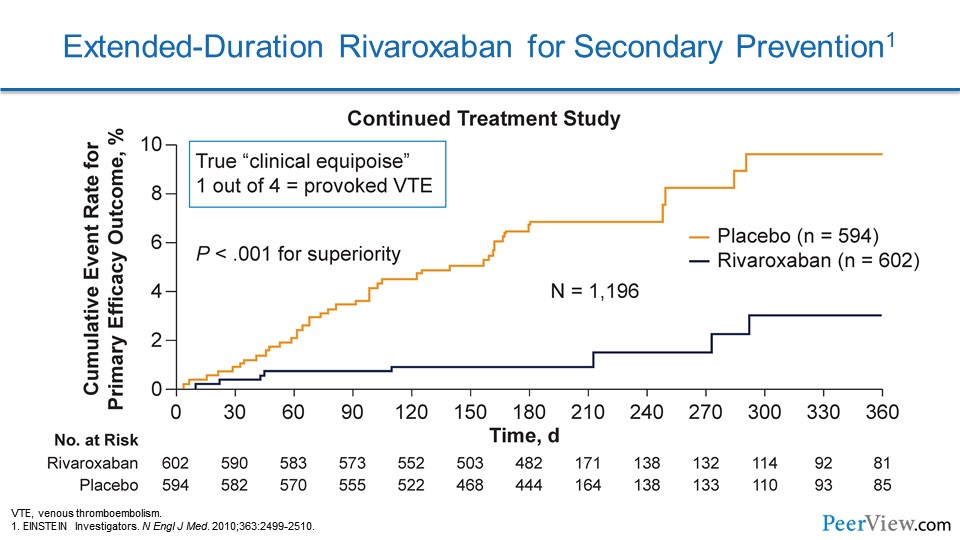

Here we see data from one of the rivaroxaban trials called EINSTEIN-DVT. In this study, they were looking at patients with DVT, and they looked at two different phases. There was the acute treatment phase and there was a second part to this study called the Continued Treatment Study. In this part of the study, patients who were treated with anticoagulants could be randomized to either keep going on anticoagulation with rivaroxaban or switch to a placebo. What's interesting here is 25% of these patients had provoked VTE, and in this population there was a marked reduction in the risk of recurrent VTE with extending out rivaroxaban therapy.

Slide 50

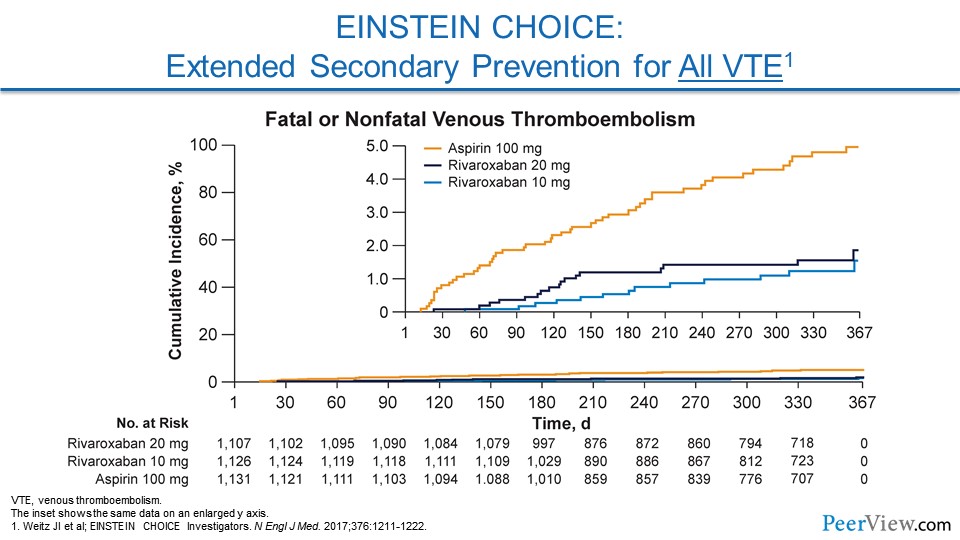

A follow-up to this study was called EINSTEIN CHOICE. In this study, patients had either VTE that was provoked or unprovoked. But in contrast to EINSTEIN-DVT, 60% of these patients had provoked VTE. And here, they looked at two different doses of rivaroxaban. Both doses dramatically reduced the risk of recurrent VTE compared with aspirin, and that rivaroxaban 10-mg dose actually was remarkably safe as well.

Slide 51

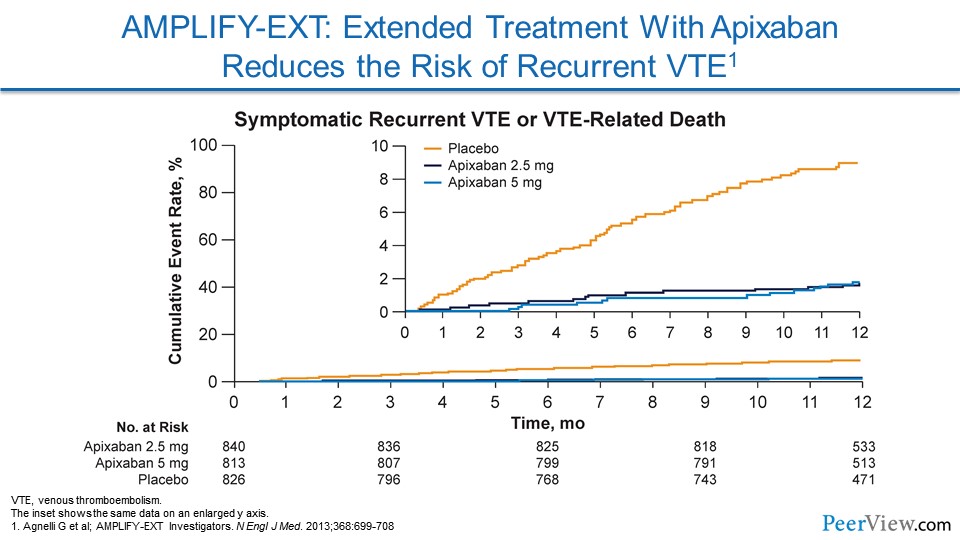

In AMPLIFY-EXT, a randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of two doses of apixaban with placebo, extended anticoagulation with apixaban at either a treatment dose of 5 mg twice daily or a thromboprophylactic dose of 2.5 mg twice daily was found to reduce the risk of recurrent VTE. In this study, net clinical benefit was defined as a reduction in the composite of symptomatic recurrent VTE, death related to VTE, myocardial infarction, stroke, death related to cardiovascular disease, or major bleeding. It is also worth noting that treatment with apixaban 2.5 mg or 5 mg twice daily significantly reduced the rate of all-cause hospitalizations versus placebo.

Slide 52

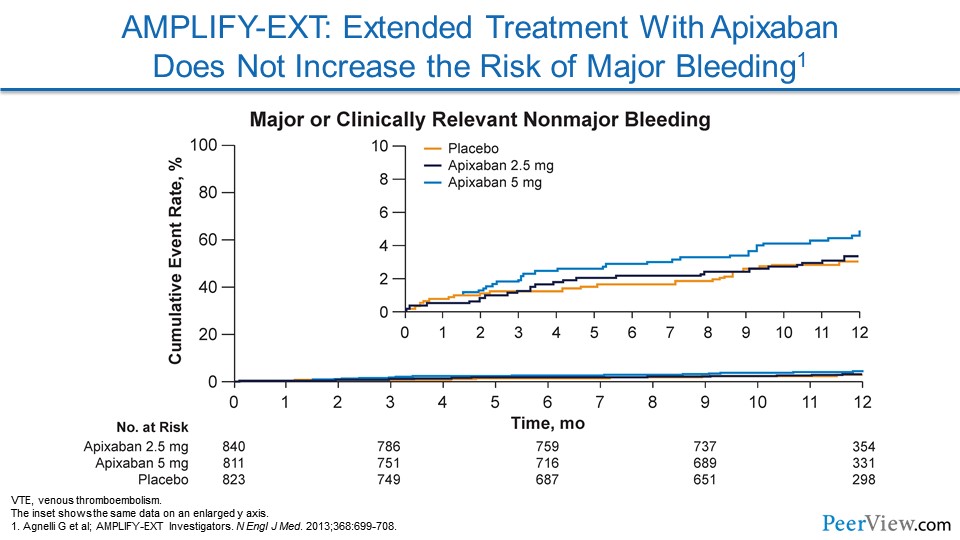

The primary safety outcome for AMPLIFY-EXT was major bleeding, but there was a secondary safety outcome that was a composite of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. As you can see in this slide, the rate of major bleeding events with apixaban was overlapped or essentially similar to placebo, especially with that apixaban 2.5-mg twice daily dose.

Slide 53

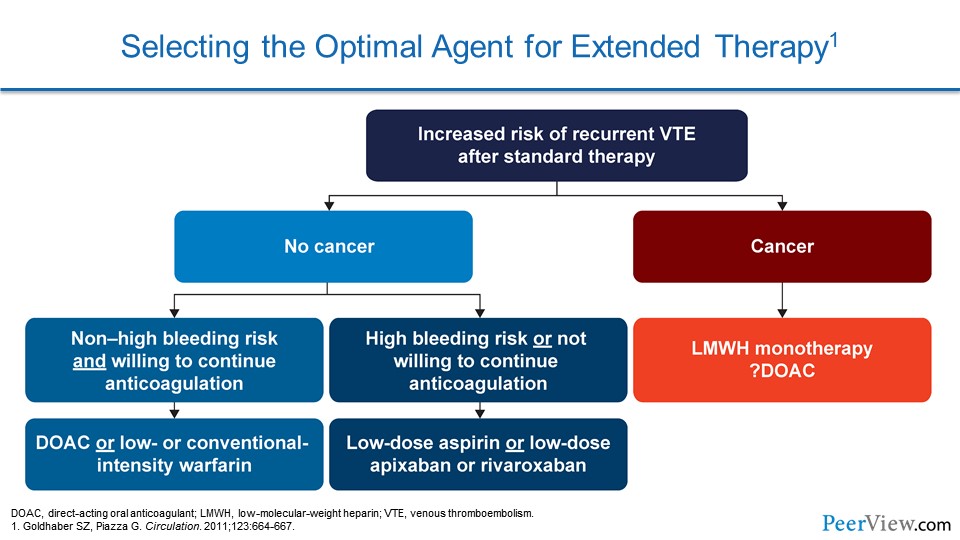

So when we consider our patients and we consider the ongoing risk of VTE, essentially what we have to do is determine the optimal duration of therapy. So when we have a patient who has increased risk of recurrent VTE after standard therapy, we have to immediately ask ourselves a question: does this patient have cancer or not?

If they have cancer, then that's a special patient population. That's a patient where we may consider low-molecular-weight heparin therapy with something like enoxaparin, because the data show that this is particularly effective in that patient population.

If they don't have cancer and they don't have a high bleeding risk, and they're willing to continue anticoagulation, we have an incredible number of options. We can use a DOAC, or we can use low- or a conventional-intensity warfarin. If they're high bleeding risk or not willing to continue anticoagulation, we can consider a low-dose aspirin or, if we talk to our patients about low-dose apixaban or rivaroxaban, they may be interested on the basis that these are actually very safe options.

Slide 54

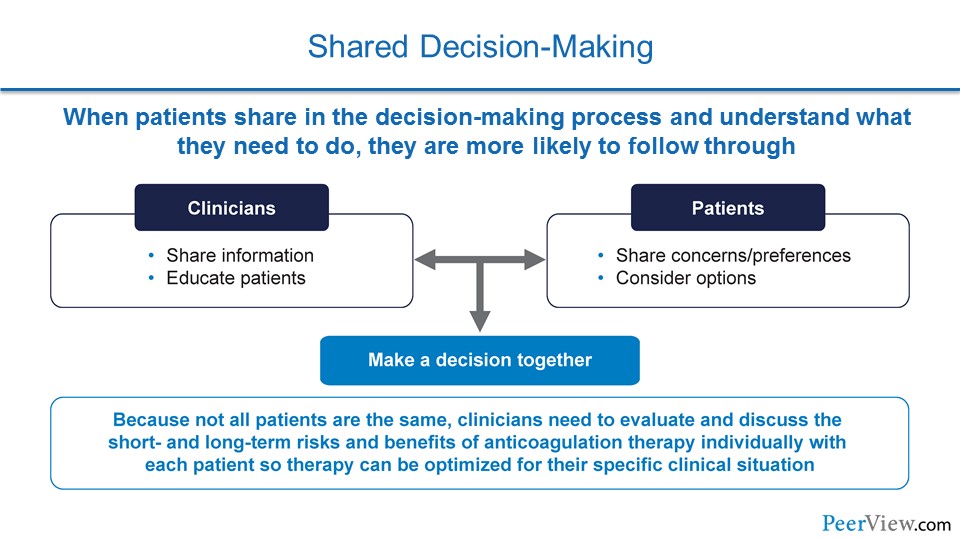

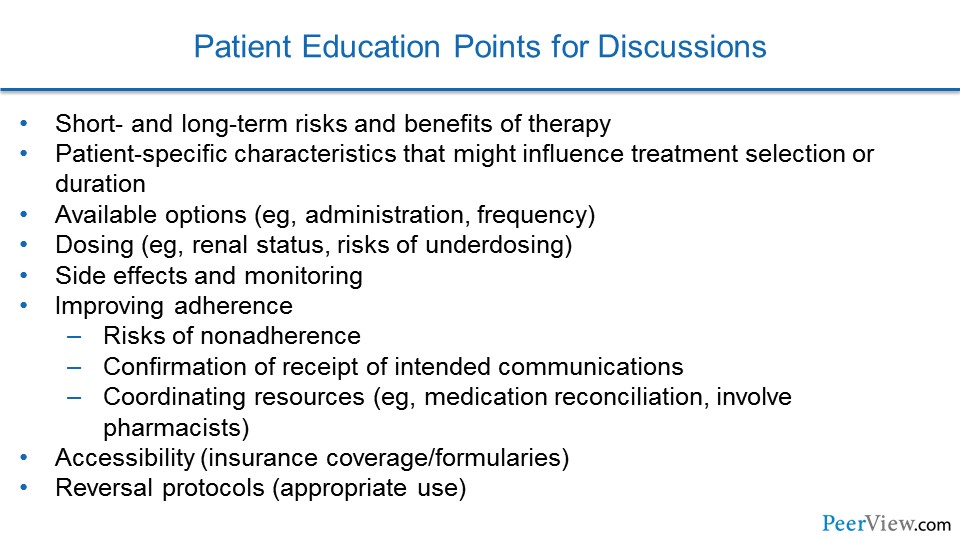

Talking to our patients about anticoagulation when they suffered VTE really requires shared decision-making. On the clinician standpoint, we have to share information with our patients and educate them about the different options, the risks, and the benefits. And patients need to express to us their concerns and their preferences, and they need to weigh out the different options, especially with a mind towards how they'll be able to adhere to different regimens of DOACs or warfarin.

Slide 55

And together, when we pool all this information, we make a decision in partnership, and this is a decision that has the best chance of being effective for our patients.

Slide 56

Now, there is a number of discussion tools that we can use to help guide shared decision-making with our patients. This is one from the North American Thrombosis Forum, and this actually points out all of the options for anticoagulation, the different dosing regimens, some of the side effects and need for monitoring, and ways that we can improve adherence in our patients.

For additional resources from the North American Thrombosis Forum.

Slide 57

To summarize, medical patients represent a population particularly vulnerable to VTE after discharge from the hospital. Extended duration thromboprophylaxis for primary prevention in very-high-risk medical patients at the time of discharge will reduce their VTE risk. For our other patients who've had VTE, VTE is actually a chronic relapsing disorder, and clinical trials have demonstrated a net clinical benefit for extended-duration anticoagulation for patients who have unprovoked VTE and for some patients with a high risk in the setting of provoked VTE. And with that, I'd like to thank you for sharing your time with me today and participating in this educational activity on applying anticoagulation best practices to reduce disease burden. Thank you so much.

Back Top