Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Module 15. Medication Safety and Error Prevention

OVERVIEW AND DEFINITION OF MEDICATION ERRORS

Each year, an estimated 1.5 million preventable adverse drug events occur, costing up to $177 billion due to patient injury and death. Approximately 1 in 20 hospital admissions can be traced to problems with medications, and many of these are preventable.1

One of the major goals of medication therapy management (MTM) is to prevent and resolve errors and safety risks associated with medication use. An important goal of the pharmacist is to identify and address potential errors involving medications. Therefore, pharmacists serve as essential resources in reducing and preventing avoidable errors and other safety risks in healthcare delivery.2

The definition of a medication "error" varies according to the source; some current definitions are shown in Table 1.3-5

| Table 1. Definitions of Medication Errors3-5 |

|

Medication errors are a subset of healthcare delivery errors (which can also involve errors such as wrong-site surgery or retained surgical instruments). An event does not need to cause actual patient harm to be considered an error—it only needs to have the potential to lead to patient harm or inappropriate use of a drug or device. An example might be when an existing drug allergy is overlooked when a patient receives a prescription, but the patient does not experience an allergic reaction when taking it. This counts as an error because the problem had the potential to cause harm to the patient, and could have been prevented with improved documentation. Another example might be an error this is made by a prescriber, but is caught by the pharmacist or pharmacy technician. It is always good to catch or intercept an error before it causes harm—but it would be counted as an error nonetheless. The NCC MERP system for categorizing the severity of medication errors is shown in Figure 1.3

|

WHAT CAUSES MOST MEDICATION ERRORS?

A study based on a large voluntary error reporting database reported that the most common types of medication errors are omission errors (failure to administer an ordered drug), followed by improper dose or quantity of a drug and other general prescribing errors.6

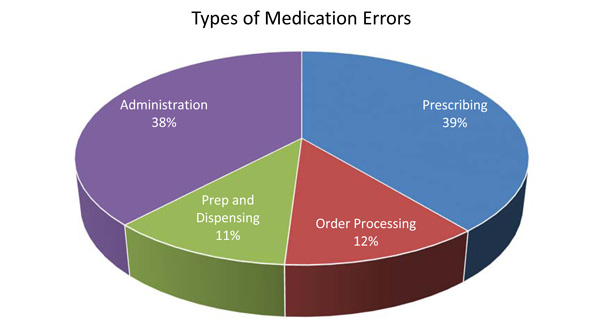

Common types of medication errors are broken down in the pie chart below (Figure 2). Of the roles that directly involve pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, prescription order processing is thought to be responsible for about 12% of all medication errors, while preparation and dispensing cause about 11%.7

| Figure 2. Types of Medication Errors and Causes |

|

| Adapted from data in Lisby M, et al. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(1):15-22.7 |

Among reported errors, approximately 1.7% are associated with documented harm to the patients. Some types of errors are more likely to be associated with harmful effects on patient outcomes, including using the wrong administration technique or route or using an incorrect dose or quantity of a drug, or an unauthorized or incorrect drug (Figure 3).6

| Figure 3. Types of Medication Errors Associated With Harm to Patients6 |

|

| Based on MedMarx inpatient data from 775,383 records associated with 83,863 reported error types. Adapted with permission. |

The information in Figures 2 and 3 is based on inpatient data, thus it may not reflect medication safety in the outpatient setting. However, an examination of 10-year data from the National Center for Health Statistics indicated that over 4.3 million emergency department and outpatient clinic visits each year are attributable to adverse drug events (ADEs).7 Outpatient ADEs resulted in 107,468 hospital admissions annually, with older patients at highest risk for hospitalization. The risk for an ADE requiring medical care increased for patients who took 3 or more medications, suggesting a role for better management of multiple medications in the MTM setting.

CAN MEDICATION ERRORS BE PREVENTED?

Given that "to err is human," how can more medication errors be prevented? Does the answer lie in more automated systems to reduce human error, or a greater layering of checks and balances? According to psychologist James Reason, there are 2 different approaches to viewing the concept of medical errors (and errors of organizational systems in general).7

The "person" or human approach focuses on the errors by individuals and blames them for forgetfulness or inattention that allow errors in patient care to happen. Taking this viewpoint may lead to corrective efforts aimed at "naming, blaming, and shaming." This approach does not address the underlying factors that contributed to the error.

Nationally recognized patient safety and health care quality organizations now endorse the "system" approach. This approach accepts the fact that humans are fallible and errors are to be expected, even in the best of circumstances. Errors are seen as consequences, rather than causes, or a flaw or hole in the system. Corrective efforts are aimed at identifying how the internal safeguards failed to catch the problem.

If enough checks and balances exist, and if reported in a direct and timely manner, the error can be caught before it causes harm. This theory can be illustrated using the “Swiss Cheese” model of error prevention. According to this model, many layers of defense may exist to prevent hazards and accidents, but within each layer there are usually one or more minor flaws or “holes.” If the holes are too prevalent, or are aligned with each other, an accident or error is more likely to slip through and cause harm (Figure 4).7

| Figure 4. Swiss Cheese Model of Error Causation |

|

| Source: Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):768-770.7 |

The Swiss cheese model is applicable to common medication errors that affect pharmacy practice. For example, if the flaw starts with a physician failing to give the patient clear instructions about how to use a medication (error #1), the pharmacist does not confirm with the patient if he or she understands the information (error #2), and the patient does not (or cannot) read or independently verify the instructions (error #3), the holes may line up to allow an error in medication if the patient takes the medication incorrectly.

Other Swiss cheese-type errors may be related to flaws in the "system," including electronic prescribing systems used during transitions of care.

HOW MEDICATION SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS MIRROR STEPS OF MTM

Interestingly, some of the recommended solutions to the problem of medication errors closely mirror steps involved in MTM. For example:

Institute of Medicine, Preventing Medication Errors2

- Allow and encourage patients to take a more active role in their own medical care.

- Move toward a model in which there is more of a partnership between patients and healthcare providers

- [Healthcare providers should] communicate more with patients at every step of the way and make that communication a two-way street, listening to patients as well as talking to them.

National Priorities Partnership (National Quality Forum)1

- Improved communication among physicians, pharmacists, and nurses (may prevent 85% of serious medication errors)

- Expand care teams: include a pharmacist on routine medical rounds (inpatient)

- Expand patient informed decision-making and education

- Reduce care fragmentation. Increase pharmacist follow-up in medication reconciliation (may reduce preventable errors by 88%)

Joint Commission Ambulatory Health Care National Patient Safety Goals8

National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) 03.06.01 recommends that providers" maintain and communicate accurate patient medication information." This includes:

- Understanding what the patient was prescribed and what medications the patient is actually taking

- Addressing duplications, omissions, and interactions and the need to continue current medications

- Coordinating information during transitions in care, within and outside of the organization (PC.02.02.01)

- Providing patient education on safe medication use (PC.02.0301)

- Communication with other providers (PC.04.02.01)

The Joint Commission acknowledges that the accuracy of the list is dependent on the patient's willingness to provide the information, and that obtaining a complete list from the patient may be difficult and/or time-consuming.8

CHECKLIST FOR DETECTING MEDICATION ERRORS THROUGH MTM

Overall, the steps recommended for improving medication safety and reducing errors present a strong rationale for pharmacist-led MTM services. In fact, one of the main goals of MTM is to detect previous or existing flaws in the prescribing and administration of medications. Questions that can be addressed during MTM are outlined in the checklist below. Some of these questions may be considered by the pharmacist during the medication review; others may be asked directly of the patient during the interview.

The process of MTM often reveals the presence of old, expired, or unused medications that the patient still has in his or her possession. Pharmacists and APRNs should be prepared to discuss safe medication storage and disposal practices. Some pharmacies and communities have designated take-back programs for unwanted medications. In preparation for MTM, the pharmacist should be aware of the local regulations for medication disposal, as well as any specific institutional recommendations. The Office of Diversion Control of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration provides detailed information about safe drug disposal.9

The following checklist is representative of the types of issues a pharmacist may consider in an MTM setting related to medication safety. This list is not necessarily exhaustive; pharmacists and APRNs should take advantage of many excellent resources on medication safety, some of which are listed in the Resources box in this module.

MEDICATION SAFETY, PRESCRIBING OR DOSAGE ERRORS

- Are there contraindications to the drugs prescribed for this patient?

- Are there any potential allergies, drug–drug, or drug–food interactions?

- Does the patent have any hepatic or renal impairment that may affect dosing?

- Are there any potentially serious adverse events associated with the medications?

- Is the patient aware of the warning signs associated with adverse drug effects, if any? Does the patient/caregiver know what to do if these occur?

- Has this patient had any previous problems related to medication safety?

- What are the potential medication safety risks/issues specific to this patient?

ACCIDENTAL OVERDOSE OR INCORRECT USE OF MEDICATIONS

- What is the patient's system for taking the medications?

- Is packaging clearly labeled? Could any pills be confused with another?

- Could the patient benefit from a pharmacist-provided bubble pack or other dispensing aid?

- Is there a current, easily accessible instruction guide for all medications, in case the patient forgets how and when to take the medications?

- Are there special dosing skills/equipment needed (e.g., injectable medications, nebulizers?) If so, does the patient have everything required to use it properly?

MEDICATION SAFETY IN THE HOME: CHILDREN, PETS, AND DRUG DIVERSION

- What are the potential hazards in the patient's household?

- Might others have access to the drugs? (Cleaning/maintenance personnel)

- How and where are the medications stored?

- Are there ways to improve safety of the current system?

DISPOSING OF EXPIRED/UNUSED MEDICATIONS

- Are there old medications (Rx and OTC) or supplements in the home?

- What is the plan for disposing of these medications?

- What are the local guidelines for disposing of these medications?

- Is there a take-back program or other service the patient can use?

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Safety and error prevention are integral aspects of MTM practice. Pharmacists have extensive training and experience in error prevention and detection, and should look for ways to incorporate these skills into MTM recommendations. Safety considerations must be balanced with the efficacy goals for the therapeutic regimen. Additional resources for the pharmacist are provided in the sidebar, Medication Safety Web Resources.

REFERENCES

- National Priorities Partnership. Preventing Medication Errors: a $21 billion opportunity. National Quality Forum, December 2010. Availabe at: http://www.nehi.net.

- Kasbekar R, Maples M, Bernacchi A, et al. The pharmacist's role in preventing medication errors in older adults. Consult Pharm. 2014 Dec;29(12):838-842.

- Aspden P, Wolcott J, Bootman JL, et al (Eds). Preventing Medication Errors. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors. National Academies Press, 2007.

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. NCC MERP Index for Categorizing Medication Errors. 2001. Available at: http://www.nccmerp.org/medErrorCatIndex.html.

- Pathways to Medication Safety report. American Hospital Association, Institute for Safe Medical Practices, Health Research & Educational Trust. December 2002. Available at: https://http://www.ismp.org/tools/pathways.asp.

- Santell JP, et al. MedMarx Data Report. USP Center for the Advancement of Patient Safety. U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention, 2005.

- Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, et al. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(9):901-910.

- Reason J. Human error: models and management. 2000;320(7237):768-770.

- The Joint Commission. National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 1, 2016. Ambulatory Health Accreditation Program. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2016_NPSG_AHC_ER.pdf.

- S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Office of Diversion Control. Drug disposal information. Available at: http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/index.html.

Back to Top