Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Taking a New Look at Cancer-Associated Venous Thromboembolism: How Is Emerging Evidence Influencing Guidelines & Practice?

Cancer-Associated VTE: Risks and Consequences

Slide 1

Dr. McBane: Hi, my name is Rob McBane. I am a Professor of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and I am the Chair of the Division of Vascular Medicine. Today I am delighted to take us through a discussion of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism (VTE), and how the emerging evidence influences guidelines and clinical practice. Let's just spend a few moments talking about the epidemiology of this problem.

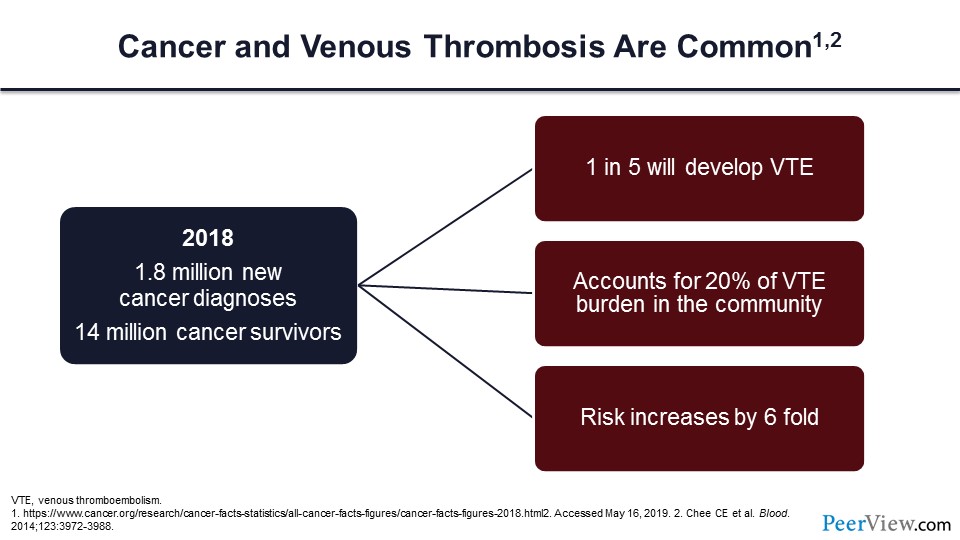

Cancer, as you all know, is common. In 2018, there were nearly two million new cancer diagnoses in our country, and currently we have 14 million cancer survivors. One in five of these individuals will develop a VTE, and this accounts for nearly a fifth of the VTE burden in our community.

We know that cancer increases the risk of VTE by more than six-fold and not only for the incident venous thrombosis (VT), but also the risk of VT recurrence is greatly increased by more than six-fold. For those individuals who have had cancer and a VT event and are not able to take anticoagulants, we know that the annual risk of recurrence is more than 30%.

Slide 2

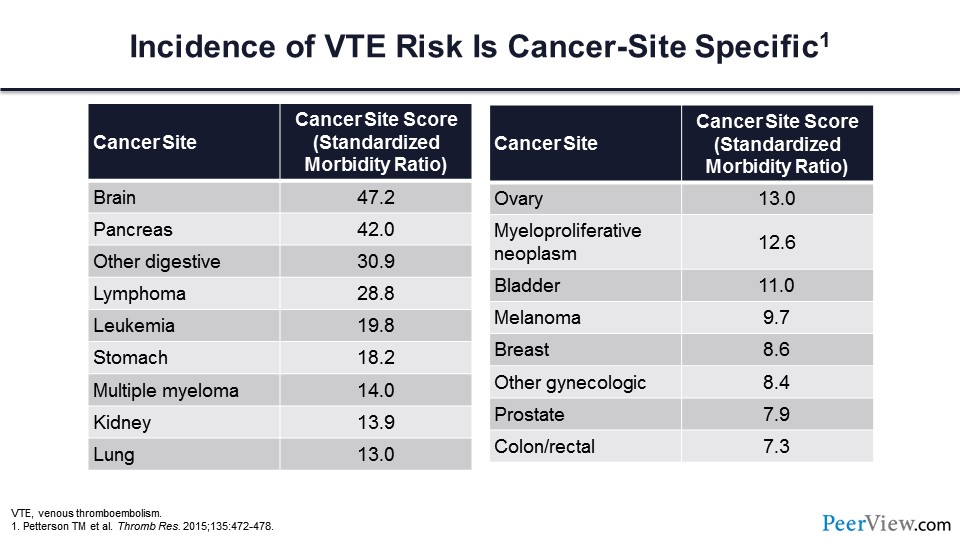

Further, we know that incident VT is cancer-site specific. Each of the malignancies carries an increased risk of thrombosis relative to patients without malignancy. However, as you can see in slide 2, there are several cancers that are particularly prone to developing thrombosis, but in general, brain cancer, pancreatic cancer, cancer involving the upper GI tract, and lymphoma stand at the top of the risk for cancer-associated thrombosis.

Slide 3

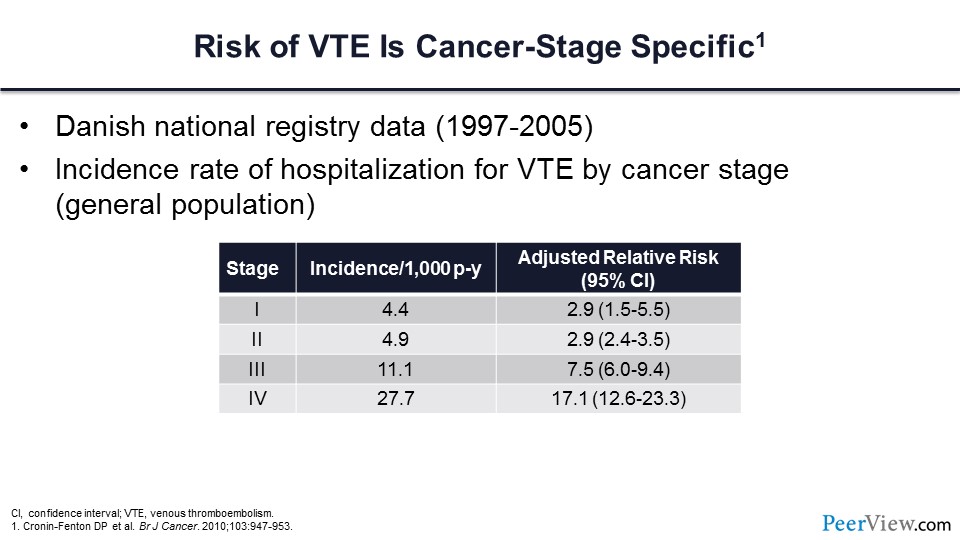

We know that the risk of VTE is cancer-stage specific. In this very large population of patients from a Danish National Registry, those individuals who have stage III and IV cancer have a greatly increased risk of VT compared with those with lesser stages.

Slide 4

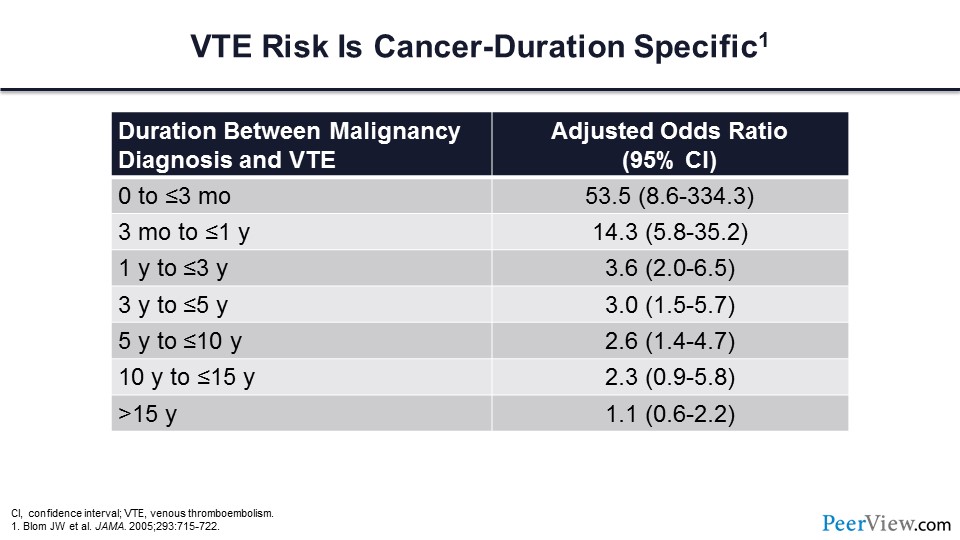

We also know that the risk of VTE is cancer-duration specific. As you can see from the table in slide 4, most of the thrombotic events are going to occur within the first 3 months of cancer diagnosis.

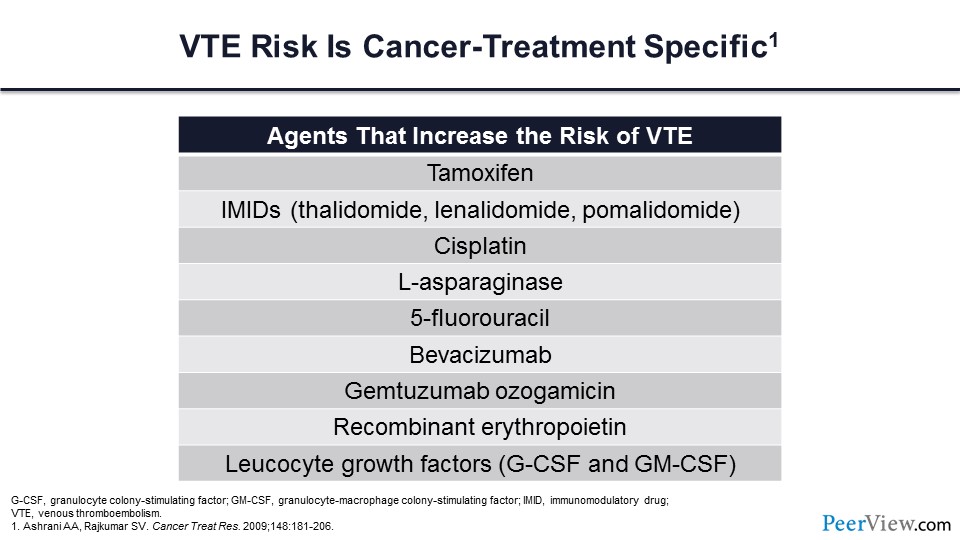

Slide 5

We also know that this risk is directly related to cancer-specific treatment. Those individuals who are actively receiving chemotherapy have a nearly seven-fold increased risk of VTE compared with patients with cancer who are not receiving chemotherapy. This table shows a number of the chemotherapeutic agents that are particularly prone to increasing the risk of VT.

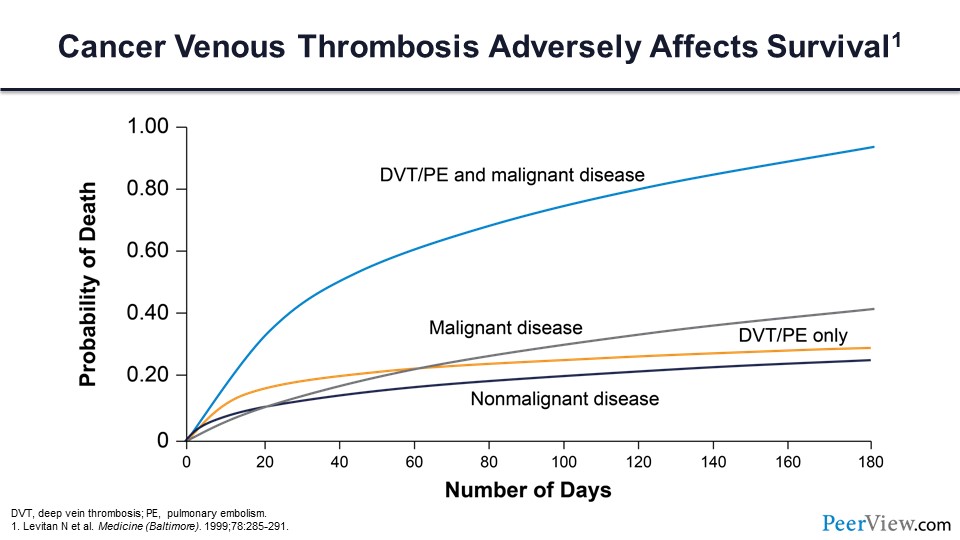

Slide 6

We know that cancer-associated VT adversely impacts survival for our patients with malignancy. Those patients who have a cancer and an associated VT have a greatly increased risk of mortality compared with patients who have the same malignancy but don’t have a VT diagnosis. We know that VT in cancer is the second-most common cause of cancer death, secondary only to cancer progression, and nearly half of these individuals will have a distant metastasis at the time of their death.

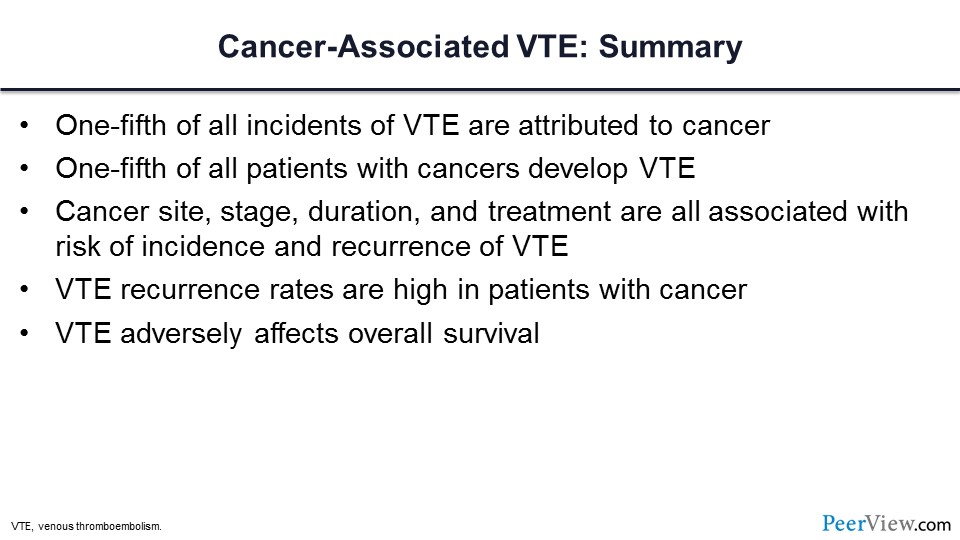

Slide 7

So in summary, one-fifth of all incident VT in our community is attributed to cancer, and a fifth of all cancer patients will develop a VTE event. We know that this risk is cancer-site specific, -stage specific, and -duration and -treatment specific. We know that the risk of recurrence is high in these patients and we know that VTE adversely impacts overall survival.

Cancer-Associated VTE: Emerging Evidence Is Influencing Current Guidance Regarding Thromboprophylaxis

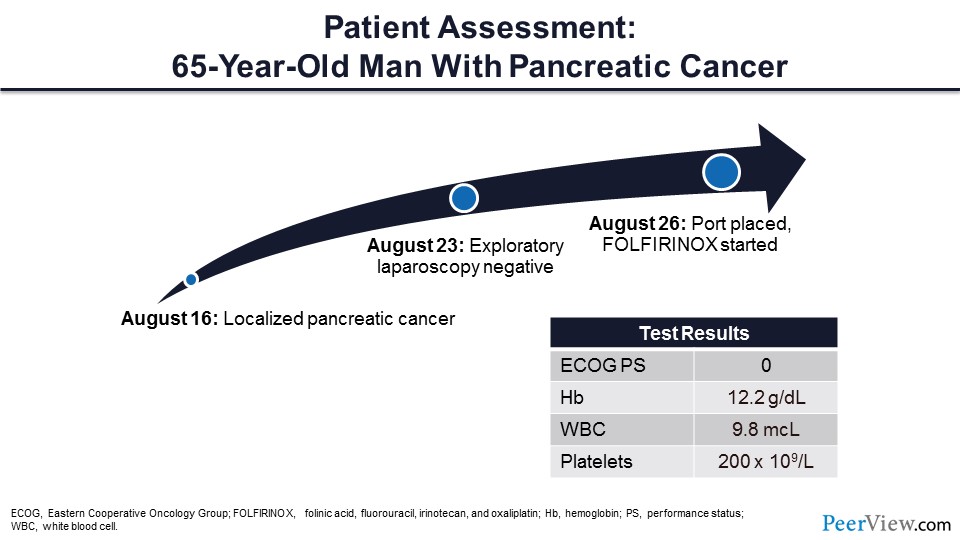

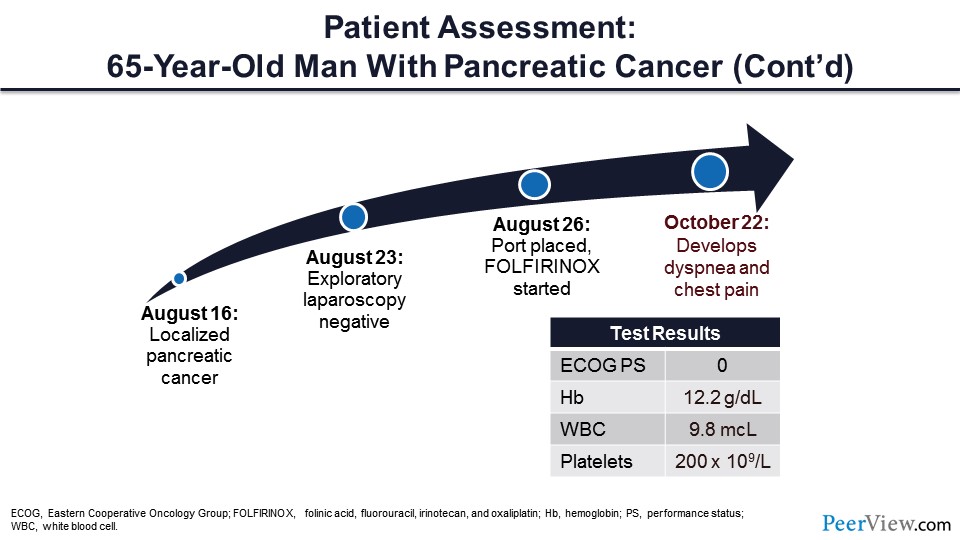

Slide 8

Next, I would like to talk about VTE prevention, and I think the best way to do this is to introduce a case. This is a patient that I saw about a year ago, and his story was that he had a new diagnosis of localized pancreatic cancer. He had a port placed and was initiated on folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin therapy. At the time that I saw him, he was actually doing quite well with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of zero and his laboratory test results were very reasonable.

So, the first question is, should this patient with localized pancreatic cancer be initiated on primary VT prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH)—yes or no? We’re going to start our discussion with LMWH, and later I’ll review the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

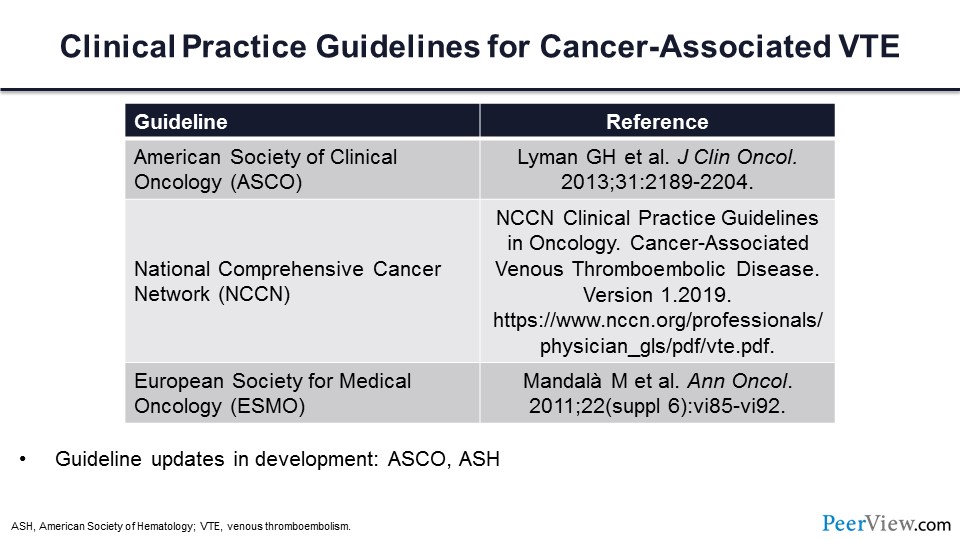

Slide 9

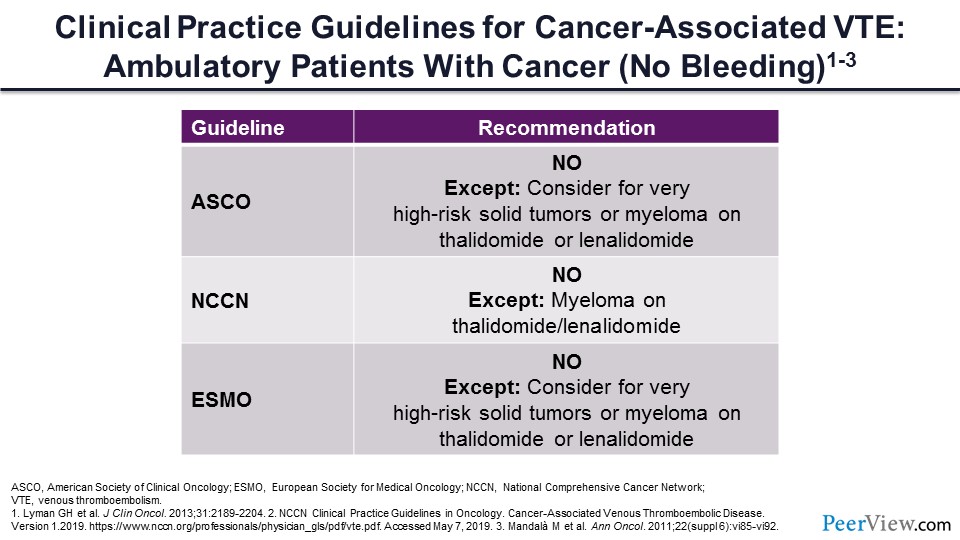

In order to address this question, it’s important to determine what the guideline statements are with respect to these three important societies. It’s also important to note that these guidelines are anticipated to be updated very soon and may change.

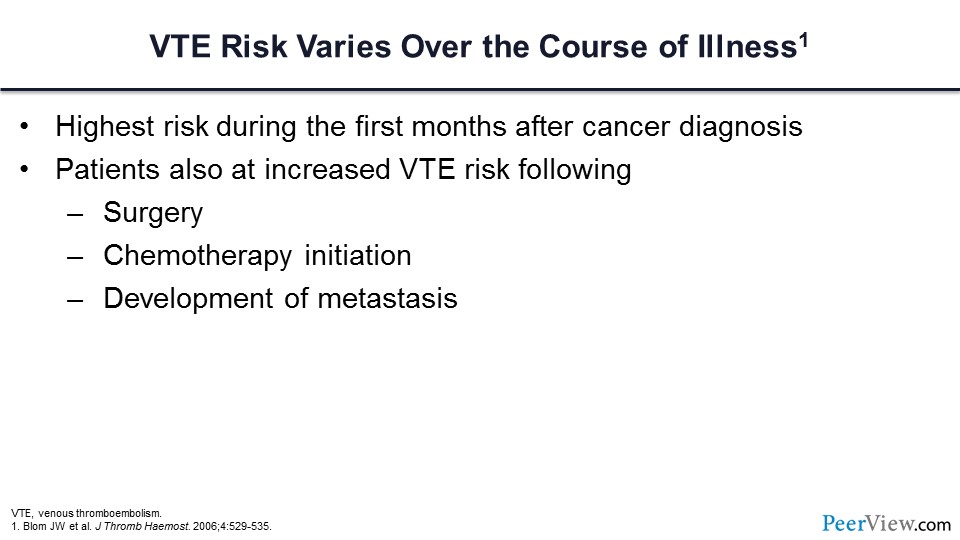

Slide 10

We know that cancer-associated VT varies with respect to the timing of diagnosis. We know that the risk varies over the course of illness and that it is highest during the first few months of the cancer diagnosis. We know that those patients who are undergoing cancer-associated surgery and following the initiation of chemotherapy have an increased risk, and there are several specific chemotherapies of concern in which we know that the risk is greatly increased. Lastly, we know that following the development of metastasis, this risk will increase.

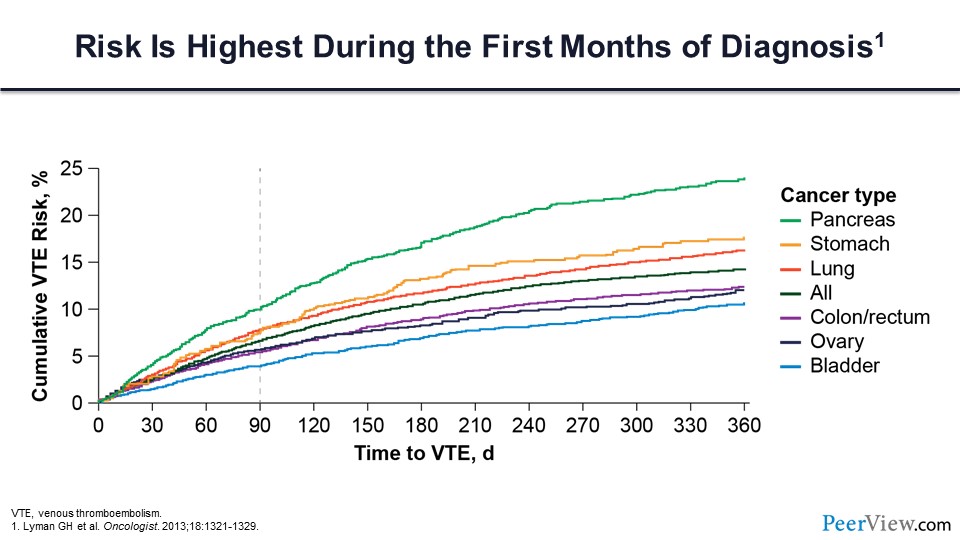

Slide 11

The figure in slide 11 highlights that the risk of VTE is highest during the first few months of the diagnosis, and the vast majority of the activity for these various tumors is occurring within the first 90 days. So the question is, does primary prophylaxis reduce the risk of cancer-associated VTE in patients who are otherwise being treated as an outpatient? For this question, there are two major trials of LMWH that we should review.

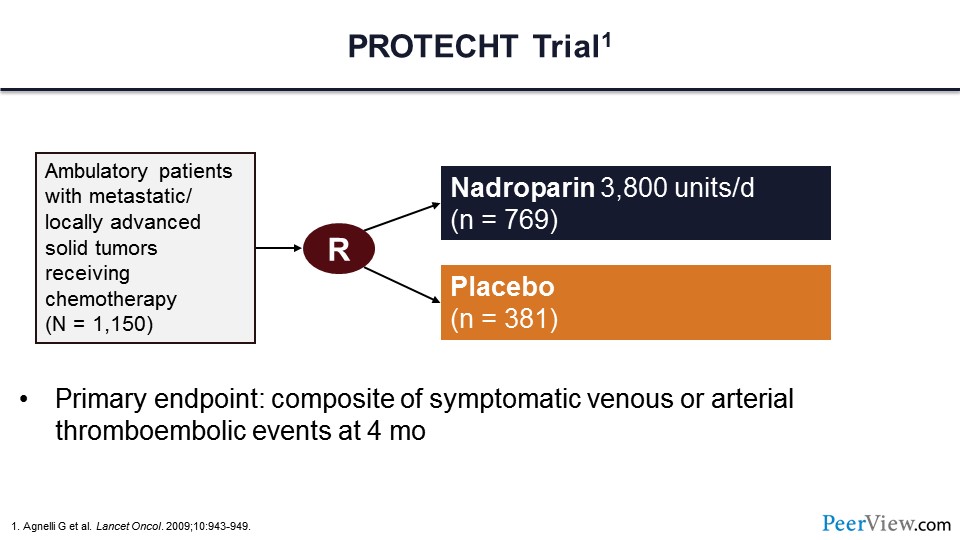

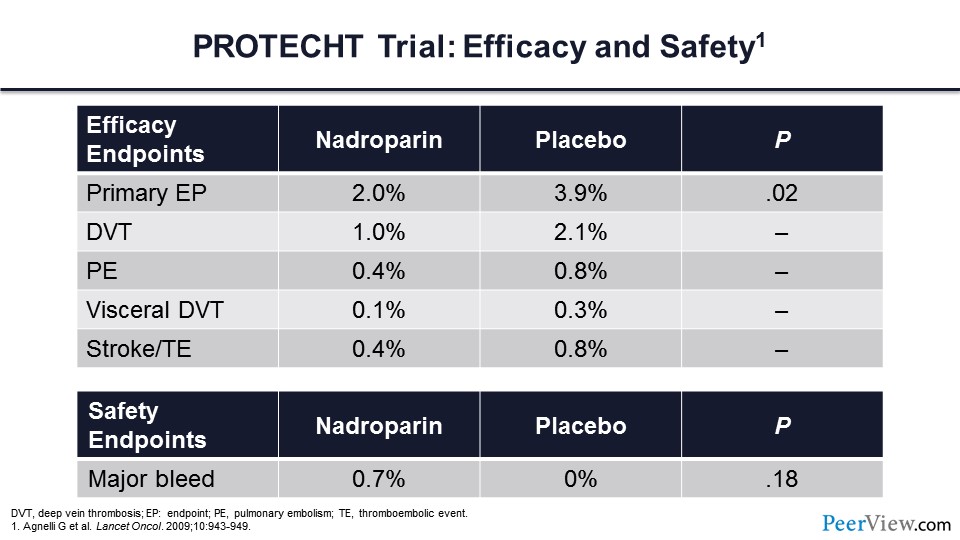

Slide 12

The first trial is the PROTECHT trial. In this trial, more than 1,000 patients were randomized to receive LMWH—in this case nadroparin—or placebo. Note that these patients were ambulatory and being treated as an outpatient. They had metastatic or locally advanced solid tumors and were receiving chemotherapy. The primary endpoint of this trial was symptomatic venous or arterial thromboembolism within 4 months.

Slide 13

Here are the primary efficacy outcomes, and what you can see is that nadroparin reduced the risk of the primary endpoint by almost 50%. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), visceral DVT, stroke, and thromboembolism were all reduced by more than 50%. This did not come at the expense of major bleeding. In this study, the rates of major bleeding in the active treatment arm were very low and did not differ from placebo.

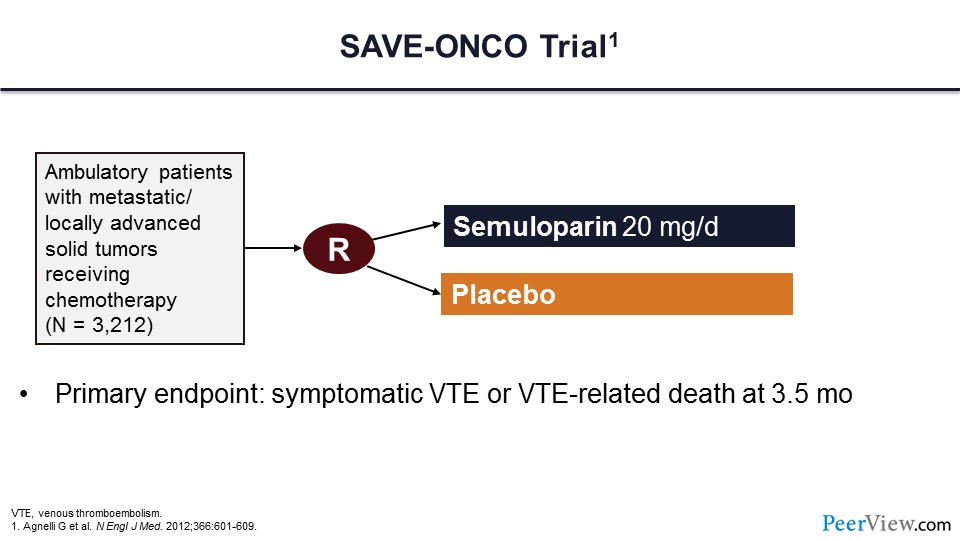

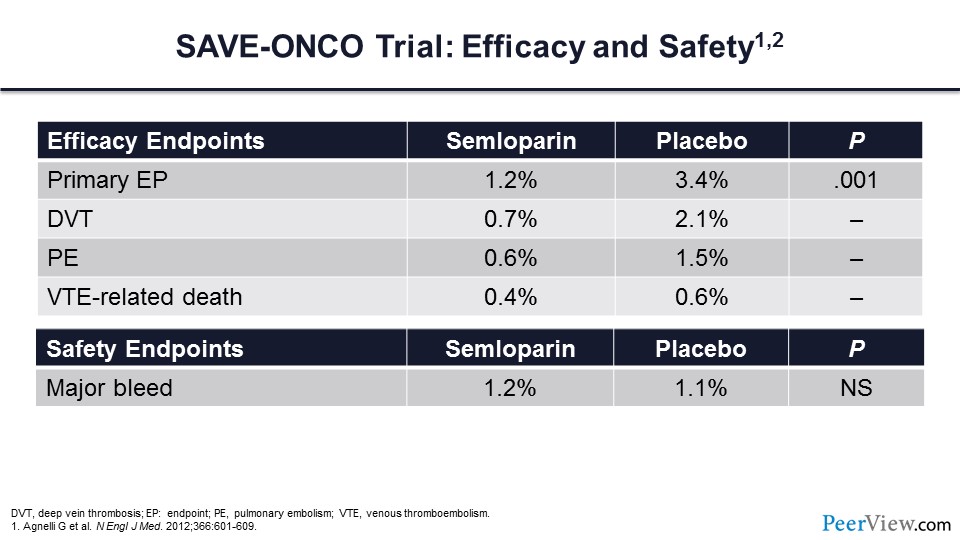

Slide 14

This second study is the SAVE-ONCO trial, which is very similar to the PROTECHT trial, with more than 3,000 patients randomized to LMWH semuloparin or placebo. As in the previous trial, the primary endpoint was symptomatic VT events or VTE-related death at 3 and a half months.

Slide 15

The primary endpoint of this trial was reduced by more than 50%, with a more than 50% reduction in DVT and PE. Note also that VTE-associated death, though lower, was not statistically significantly lower in patients who received LMWH. This therapy did not come at the expense of major bleeding, which did not differ between the LMWH arm or the placebo arm.

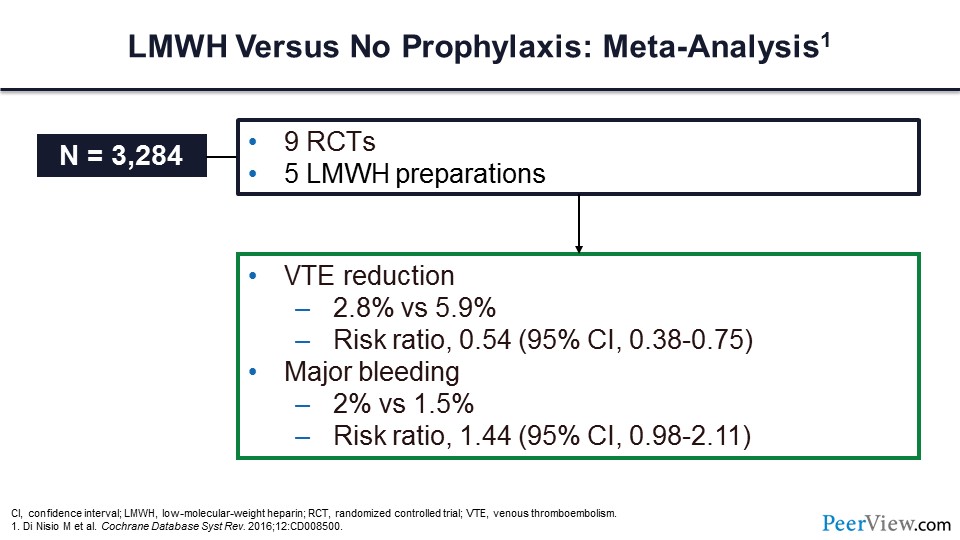

Slide 16

Slide 16 shows an important meta-analysis looking at LMWH preparations. In nine randomized clinical trials, the VTE rate was reduced by almost 50%, with a relative risk ratio of 0.54. Major bleeding was not statistically significantly greater in those individuals receiving LMWH.

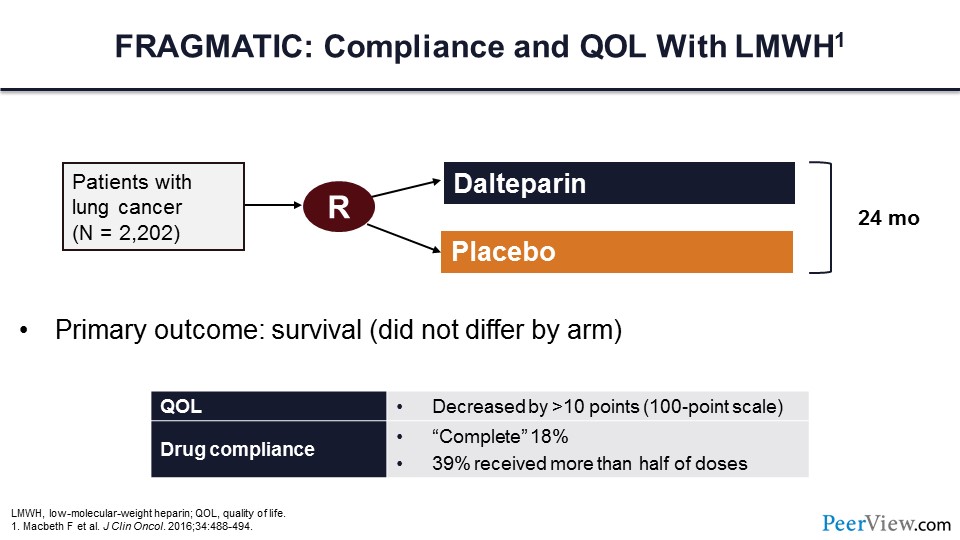

Slide 17

However, some ambulatory patients don’t particularly want to be taking an injectable parenteral medication every day, which brings us to the FRAGMATIC trial. One of the issues with the FRAGMATIC trial, which was a randomized trial of dalteparin versus placebo, was what was the quality of life and compliance to LMWH treatment? Individuals who were randomized to receive dalteparin had reduced quality of life, and in fact complete compliance with drug therapy was less than 20%. Less than 40% of patients had received more than half of the doses.

Slide 18

Let’s get back to our patient with localized pancreatic cancer. Should he be initiated on primary prophylaxis with LMWH—yes or no? The guidelines would say no. The only exceptions are those individuals with very high-risk tumors and tumor scores and patients with myeloma receiving thalidomide or thalidomide-like medications for their treatment. However, it’s important to note that these guidelines are anticipated to change with the new DOAC data recently published.

Slide 19

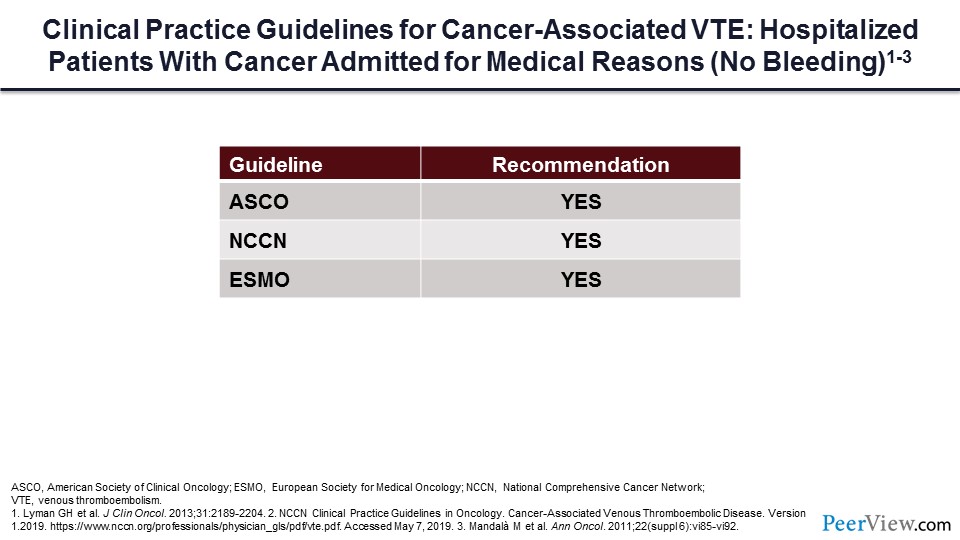

What if our patient is hospitalized for a medical complication? Should they receive prophylaxis during that setting? The guidelines universally would say yes, we should give DVT prophylaxis during hospitalization.

Slide 20

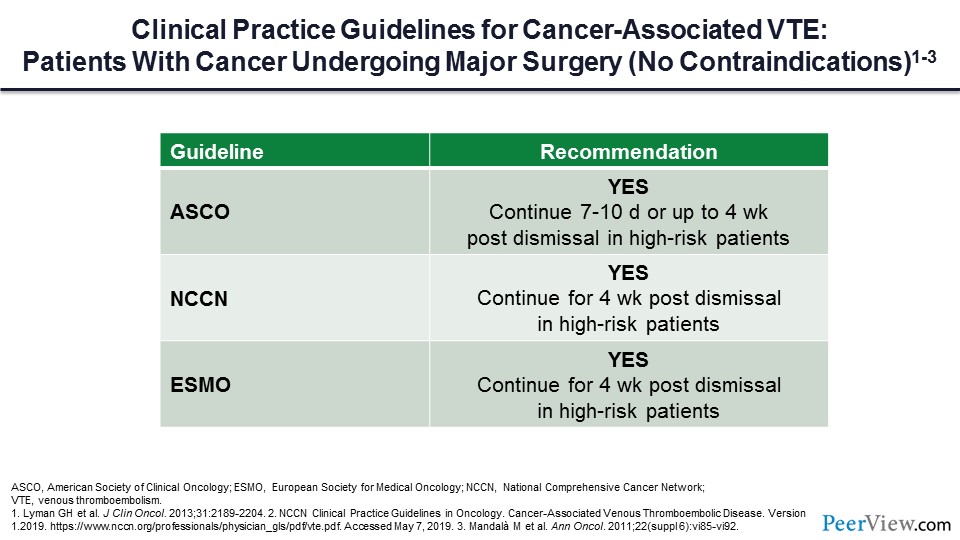

What if our patient needs to have major surgery? Should they receive primary prophylaxis in that setting? All of the guidelines would uniformly say that LMWH for DVT prophylaxis under those circumstances is very reasonable.

Slide 21

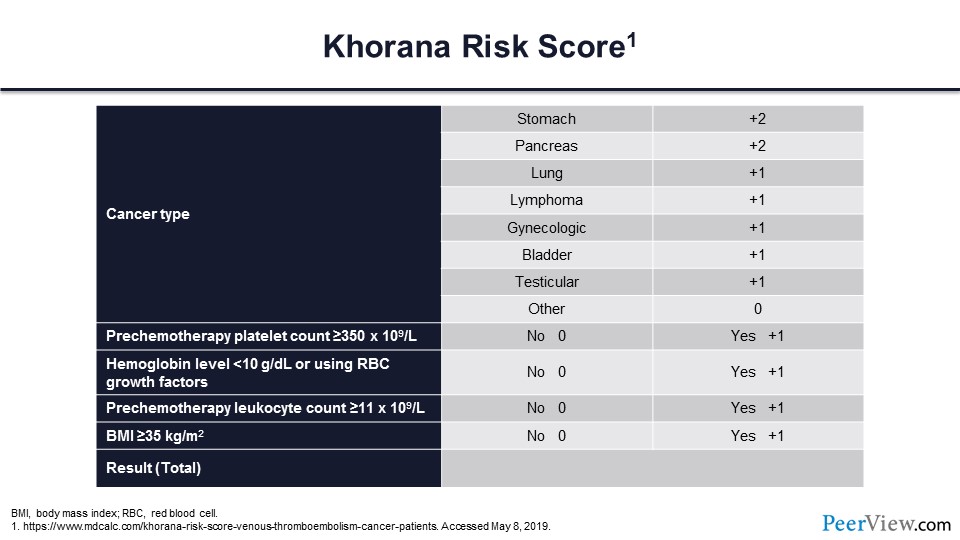

Next, let's address the question of whether risk assessment tools work to identify individuals who are most likely to benefit from primary prophylaxis. The most widely quoted risk assessment tool is the Khorana score. The Khorana score assesses risk by first determining whether the patient has a high-risk cancer type; then several laboratory tests are drawn prechemotherapy, including the platelet count, the hemoglobin level, and the leucocyte count; and then lastly a simple assessment of the body mass index is performed.

Slide 22

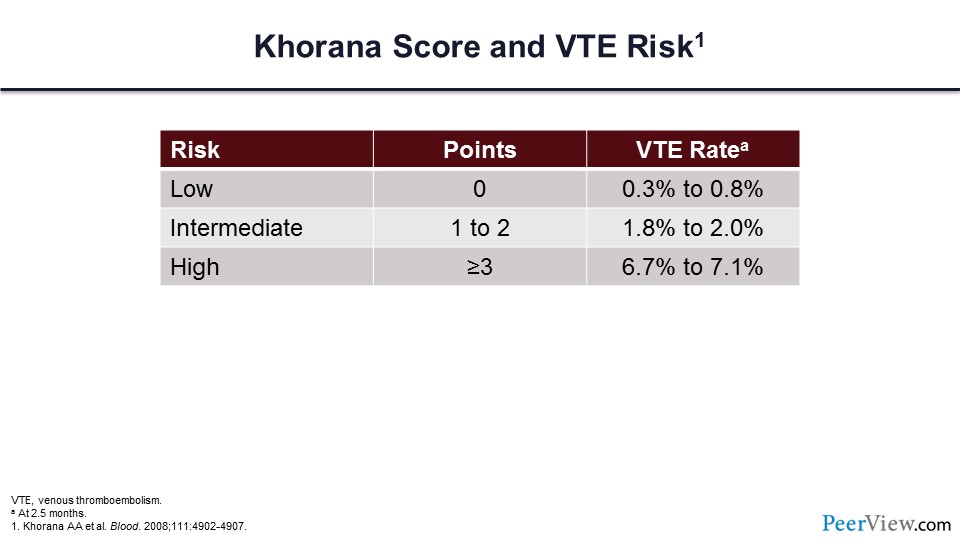

By taking each of these variables and applying them to this risk score, the patient's risk of VTE can be assigned to low-, intermediate-, or high-risk categories. In slide 22, you can see what the expected VTE rate at 2.5 months would be, depending on this risk.

Slide 23

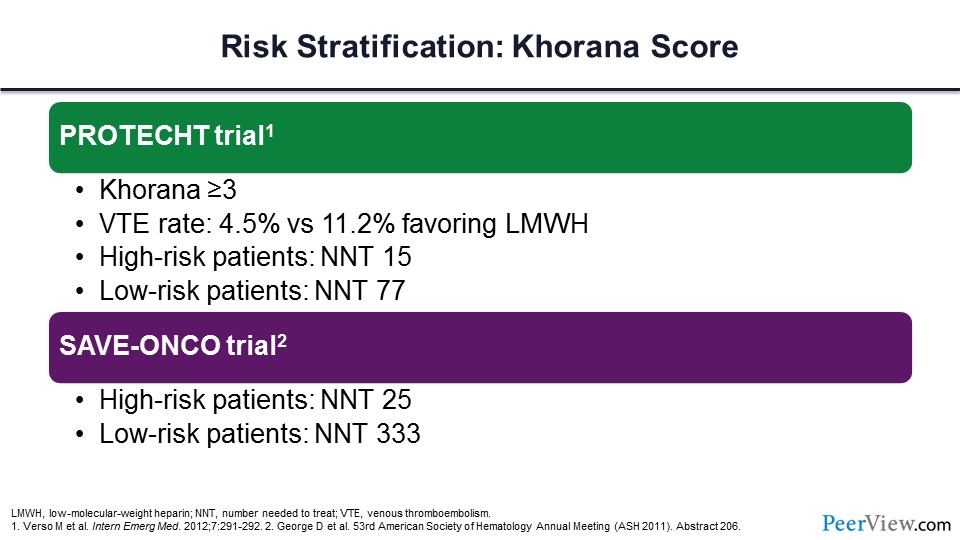

What would happen if we used the Khorana score and went back to the trials that I have already talked about and only gave DVT prophylaxis to those individuals at the highest risk, those with Khorana scores of greater than 3? You can see that if those individuals were provided with LMWH, there would be a substantial, meaningful reduction in the VTE rate, with a number needed to treat (NNT) for those high-risk patients of only 15. A very similar analysis was done for the SAVE-ONCO trial, and you can see that if we just gave DVT prophylaxis to the very high-risk patients, the NNT would be only 25.

Slide 24

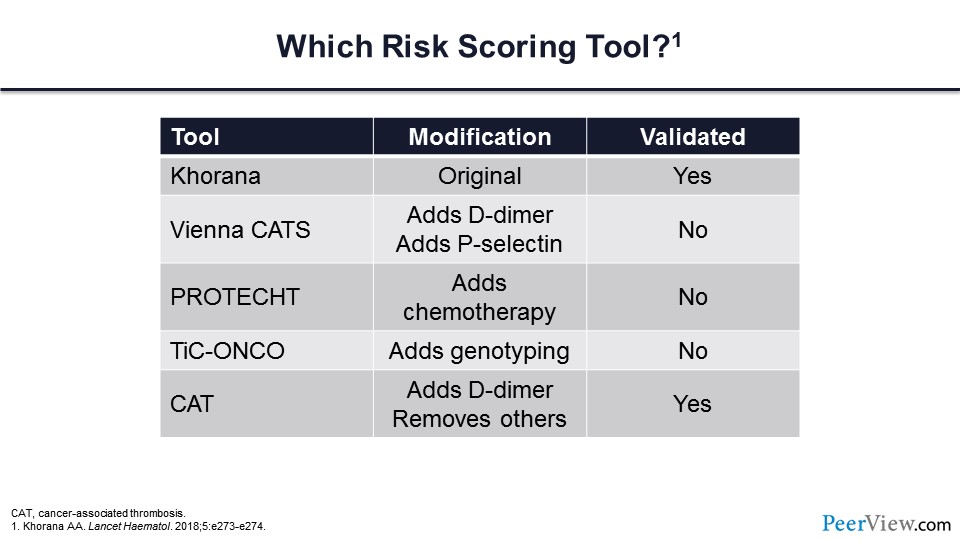

The next question is, are there other risk scoring tools? The answer, of course, is yes, and the vast majority of these have been based on the Khorana score with slight modifications. In slide 24 you can see five different risk scoring tools, and many of these have simply added on variables to the Khorana score. For example, the Vienna CATS score added the D-dimer and the soluble P-selectin measure. The PROTECHT score added chemotherapeutic variables. TiC-ONCO added genotyping, and then the CAT score added fibrin D-dimer but removed some of the other variables. You can see that some of these tools are validated and others are not.

Slide 25

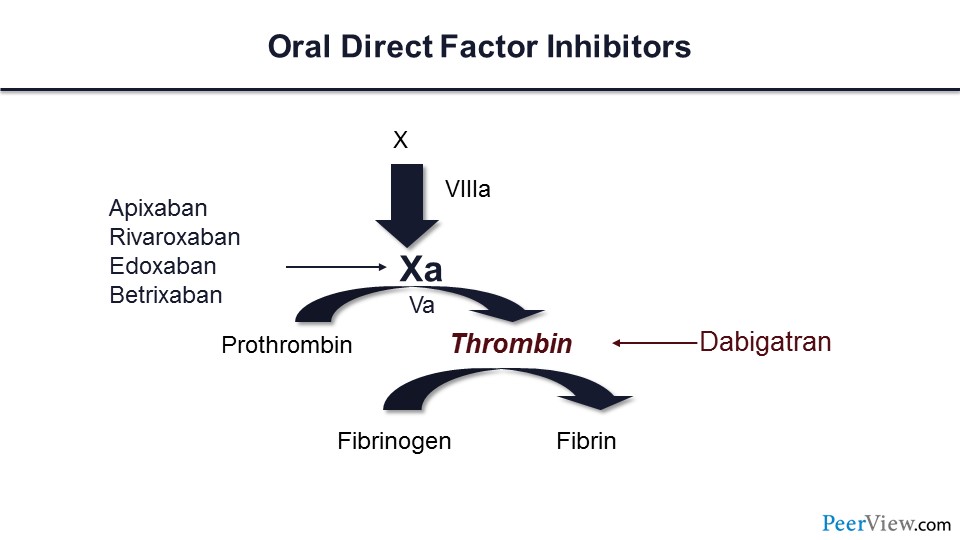

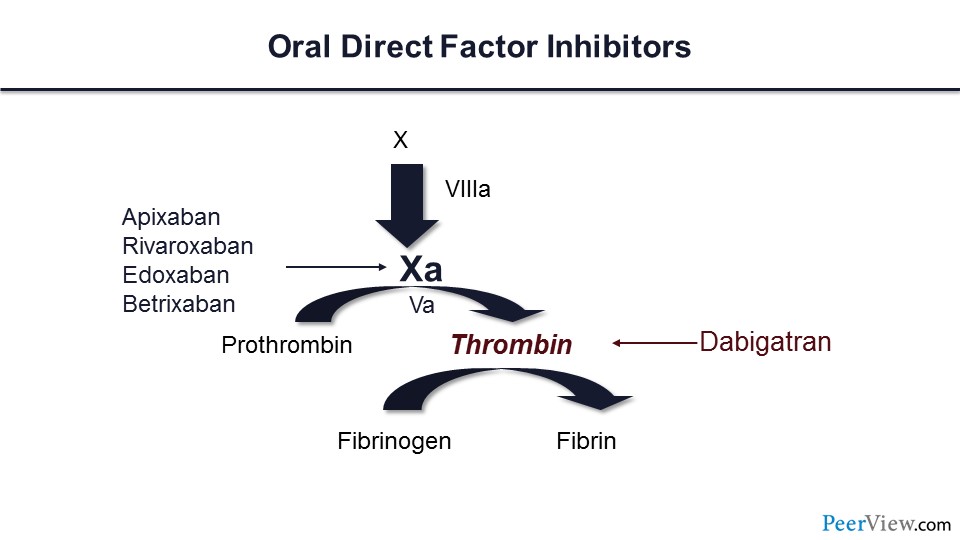

What about trials of the DOACs for VTE prophylaxis? Here are the DOACs, and you can see that there are direct factor Xa inhibitors—apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban—and one direct thrombin inhibitor. We now have data for DVT prophylaxis for apixaban and rivaroxaban for patients with cancer.

Slide 26

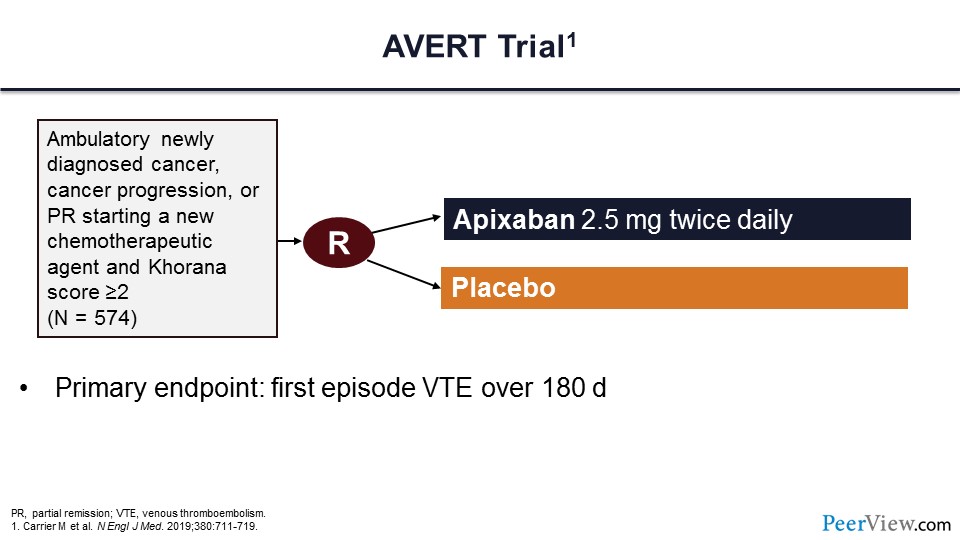

The first trial is the AVERT trial. In this trial, ambulatory patients with cancer who had cancer progression or partial remission starting new chemotherapeutic agents and importantly having a Khorana score of two or greater were assigned to receive either low-dose apixaban or placebo. The primary endpoint of this trial was the first episode of VTE at 180 days.

Slide 27

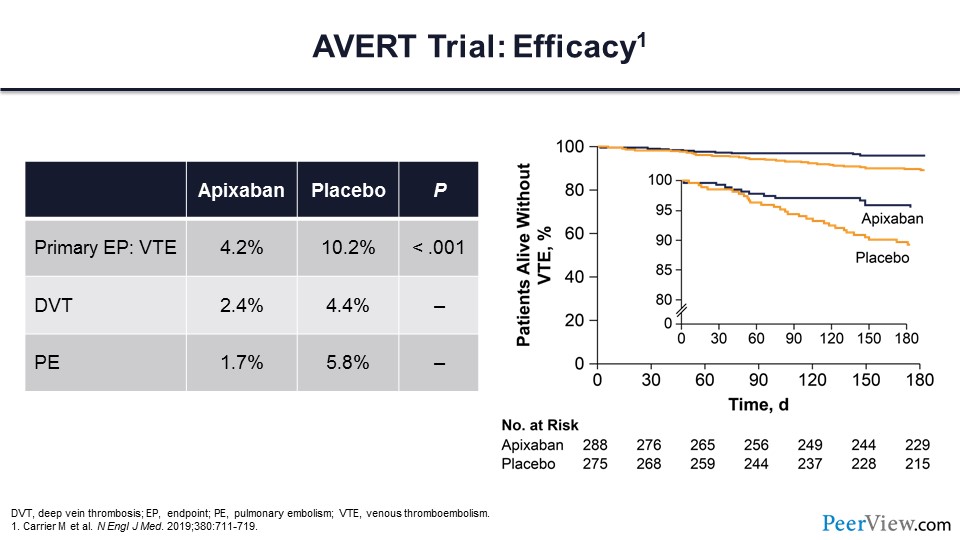

Here are the trial results. You can see that the primary endpoint was substantially lower in those patients who were assigned to the apixaban arm compared with the placebo arm. This comes with a nearly 50% reduction in DVT and with a more than 50% reduction in PE. On the right side of slide 27, you can see the Kaplan-Meier analysis of these events.

Slide 28

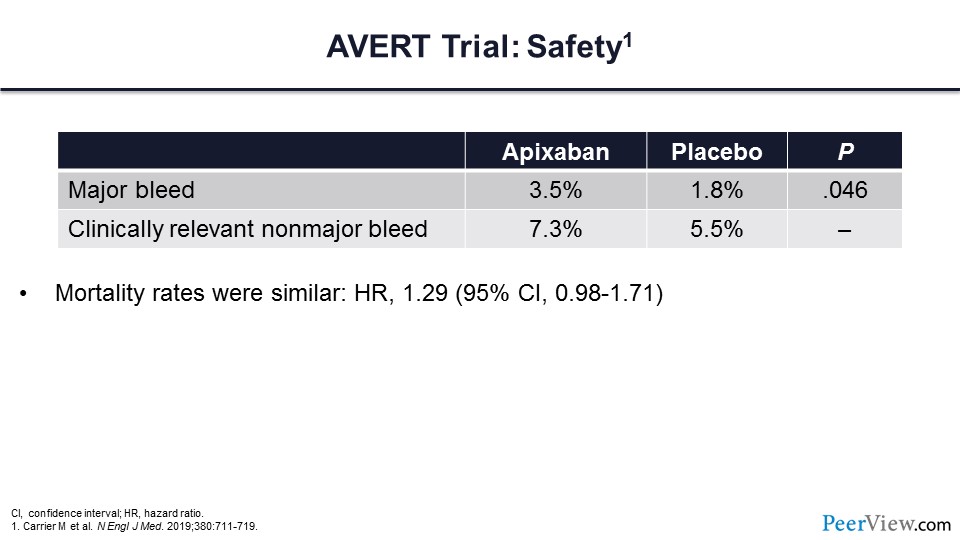

This is the safety data for the AVERT trial. There was an increased risk of major bleeding for those patients who received apixaban. The mortality rates were similar for both treatment arms.

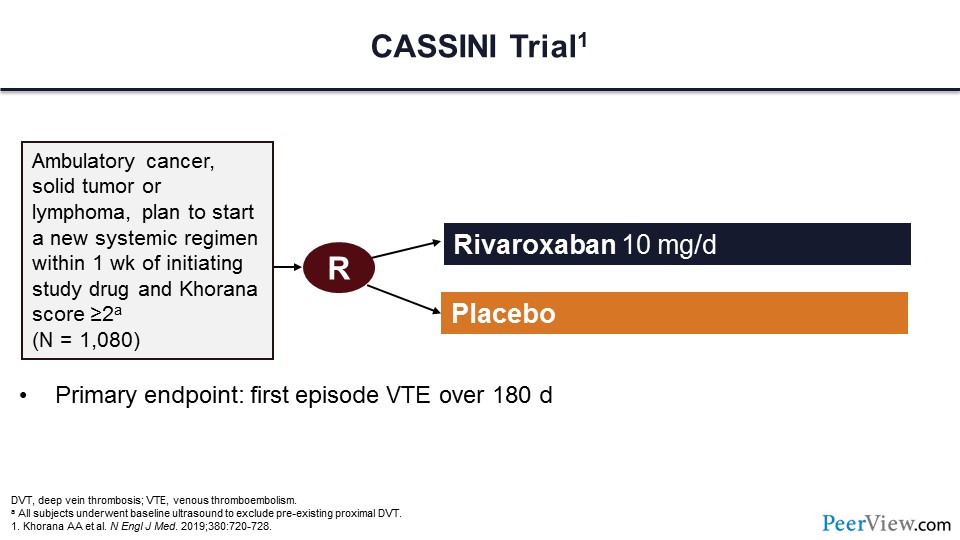

Slide 29

This second trial is called the CASSINI trial and had a very similar design compared with the AVERT trial. This trial of more than 1,000 patients randomized to a prophylactic dose of rivaroxaban or placebo was to evaluate the first episode of VTE at 180 days. Now, different from the AVERT trial, for patients getting into the CASSINI trial, they had to undergo a baseline ultrasound to exclude preexisting VTE events.

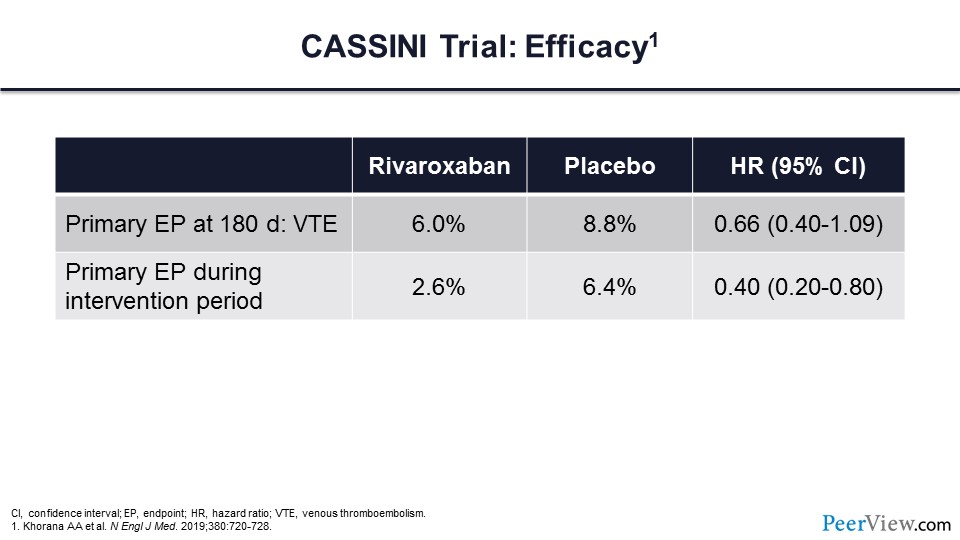

Slide 30

These are the efficacy endpoints for this trial, and you can see that the primary endpoint of VTE at 180 days was 6% in the rivaroxaban arm compared with 8.8% in the placebo arm. If one limited it to the evaluation of the primary endpoint during the intervention period, you can see that there was a more than 50% reduction of thrombotic events in the rivaroxaban arm.

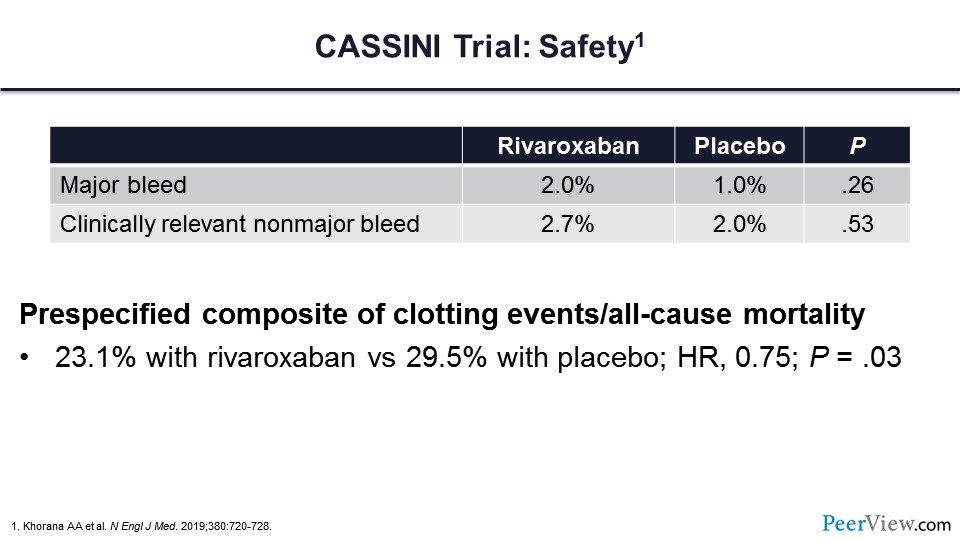

Slide 31

Major bleeding was 1% greater in those patients who received active therapy with rivaroxaban. Clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was essentially the same between the two arms.

Slide 32

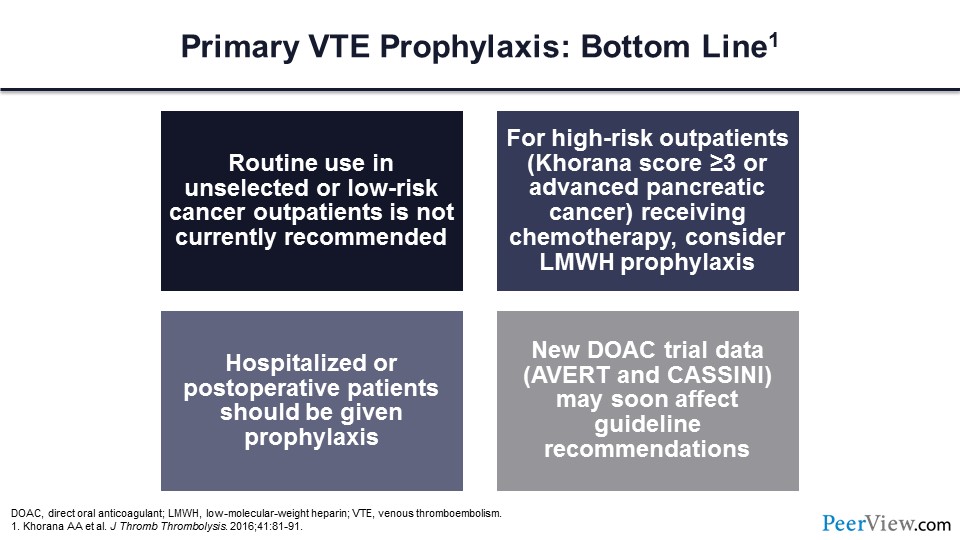

In summary, for primary VTE prophylaxis, the routine use of LMWH in unselected or low-risk patients with cancer is not currently recommended. For high-risk outpatients, those with Khorana scores of greater than or equal to 3 or advanced pancreatic cancer, one could consider LMWH prophylaxis. For hospitalized and postoperative patients, prophylaxis should be given, and this new DOAC trial data from the AVERT investigators and the CASSINI investigators may soon impact guideline recommendations for ambulatory patients with malignancy.

Cancer-Associated VTE: Emerging Evidence Is Influencing Current Guidance Regarding the Treatment of VTE

Slide 33

Lastly, I would like to discuss cancer VTE treatment. Let's go back to our patient. Remember that this was a 65-year-old male with localized pancreatic cancer who was receiving chemotherapy with folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin. Several weeks after starting chemotherapy, the patient developed dyspnea and chest pain.

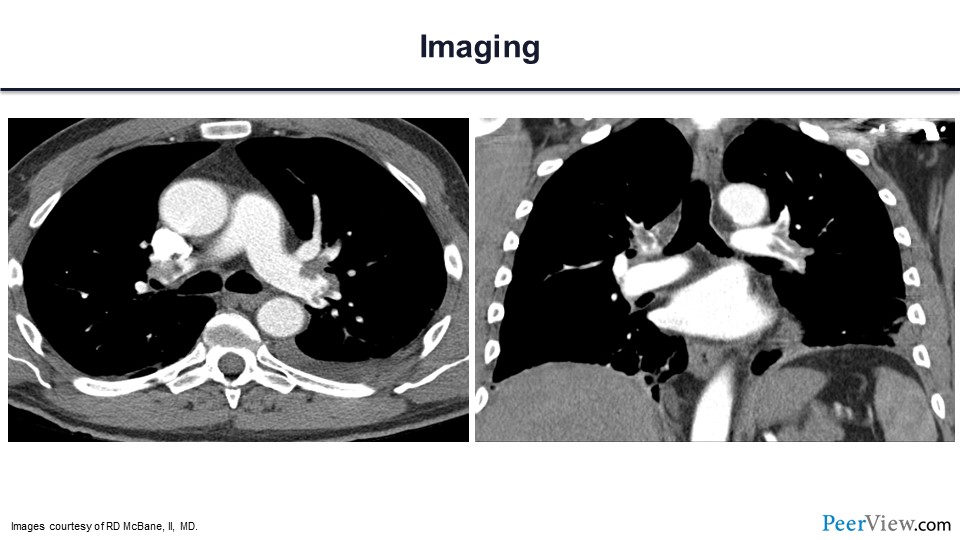

Slide 34

Here is his computed tomography scan, and you can see that there is a large volume of PE in both the right and left lobar and segmental pulmonary arteries.

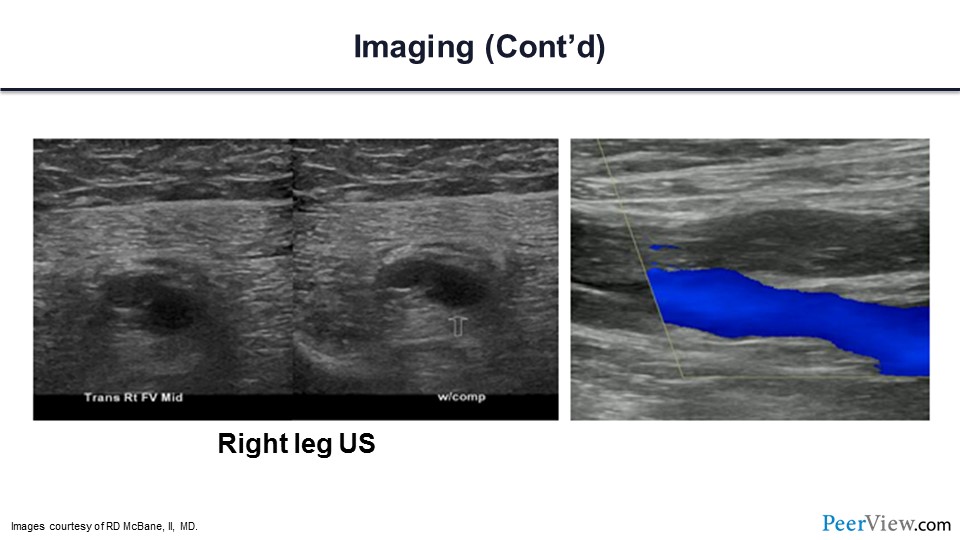

Slide 35

Here is his duplex ultrasound, and you can see that there is an extensive DVT involving the right femoral vein.

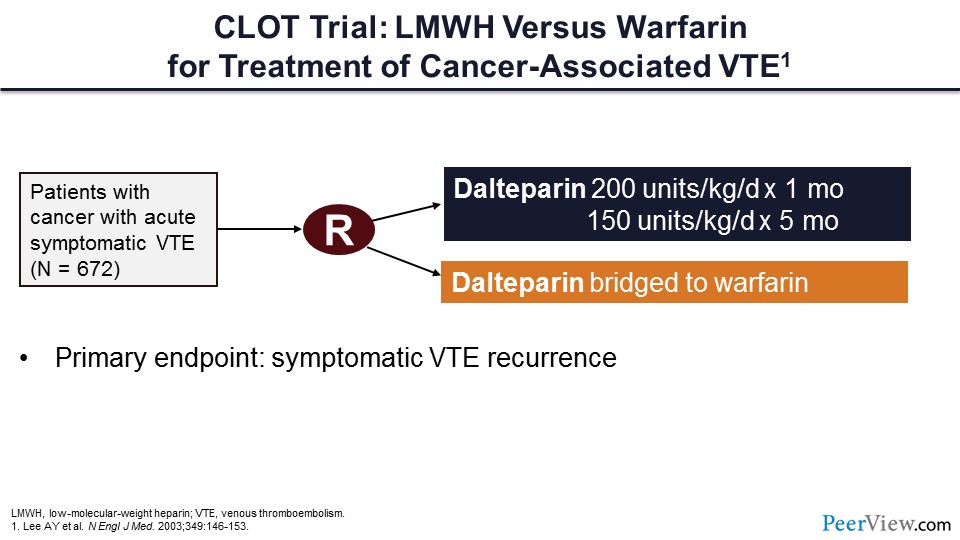

Slide 36

So, let's talk a bit about the cancer-associated VTE treatment trials. Here is perhaps the most important trial, now more than 10 years old, called the CLOT trial. To get into the CLOT trial, patients with active cancer had to have experienced an acute symptomatic VTE. In this trial, more than 600 patients were randomized to either receive dalteparin or dalteparin bridged to warfarin therapy. The primary endpoint of the trial was symptomatic VTE recurrence.

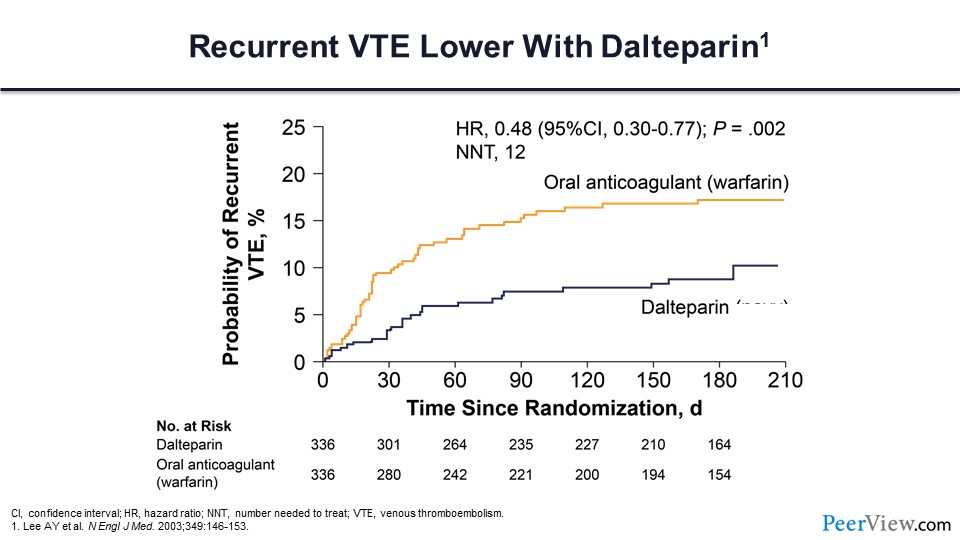

Slide 37

As you can see from this outcomes evaluation, LMWH with continued-use dalteparin significantly reduced the risk of recurrent VTE compared with warfarin, with a NNT of only 12.

Slide 38

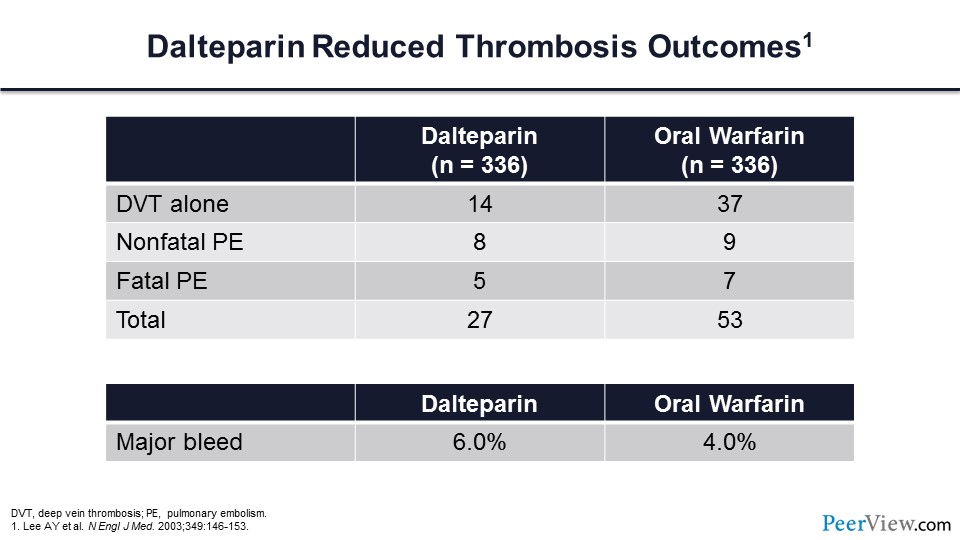

Note also that continuous therapy with dalteparin did not greatly increase the risk of major bleeding.

Slide 39

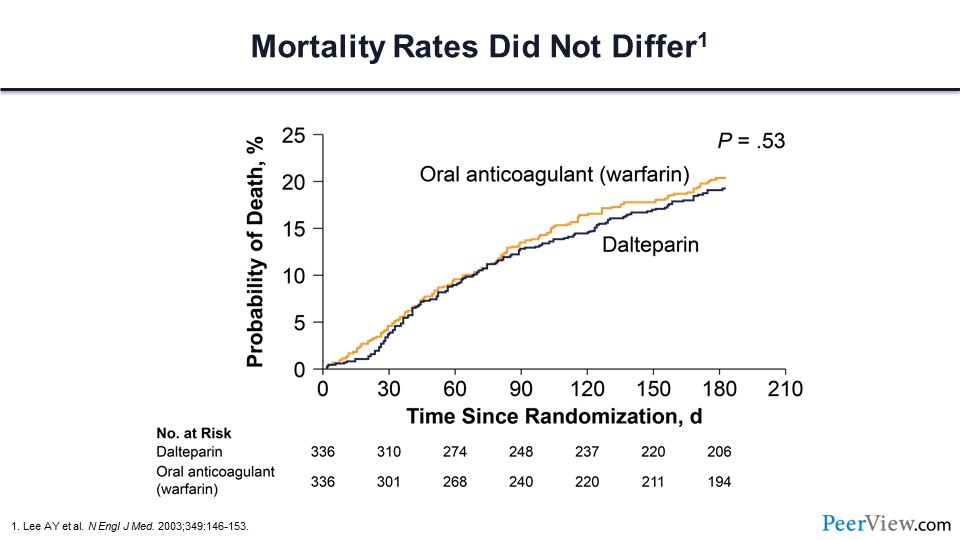

Importantly, there was no difference in survival between these two treatment arms.

Slide 40

But as you know, LMWH has limitations. The injections can be painful and can cause ecchymosis. Cost for some of our patients can be prohibitive, and many of these patients will develop thrombocytopenia related to their cancer or cancer treatment. This raises concerns about the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, which may cause treatment interruptions. We don’t have a great antidote for patients who are receiving LMWH should they bleed, and for those patients who have renal injury related to their cancer or cancer treatment, these individuals may have a limited ability to use LMWH.

What about the novel anticoagulants? Can these be used for the acute treatment of VTE in our patients with cancer? Again, here are the different choices for the novel anticoagulants. We have the direct factor Xa inhibitors and the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran. We now have data for three of the direct factor Xa inhibitors—apixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban—suggesting that this may be an effective treatment.

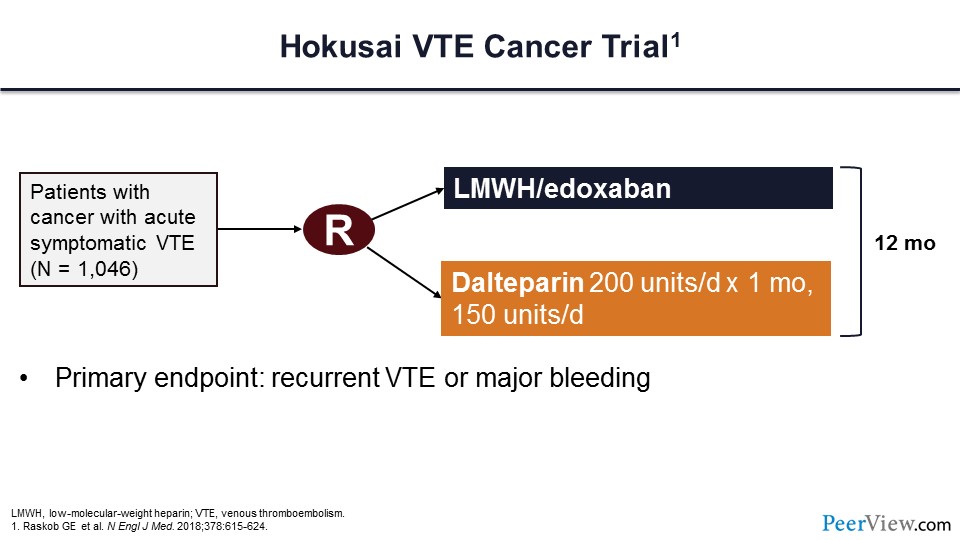

Slide 41

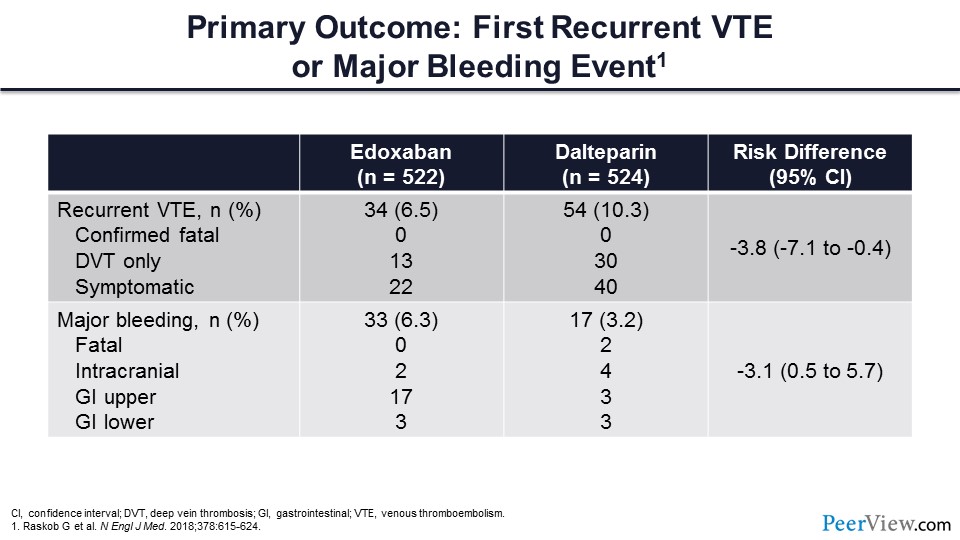

This is the Hokusai VTE Cancer trial, which assessed this hypothesis of whether the DOACs could be used for the treatment of patients with an acute VT event. In this trial, more than 1,000 patients were randomized to either LMWH transitioned to edoxaban or dalteparin as primary therapy. Therapy was to continue for at least 12 months, and the primary endpoint of the trial was recurrent VTE or major bleeding as a combined endpoint.

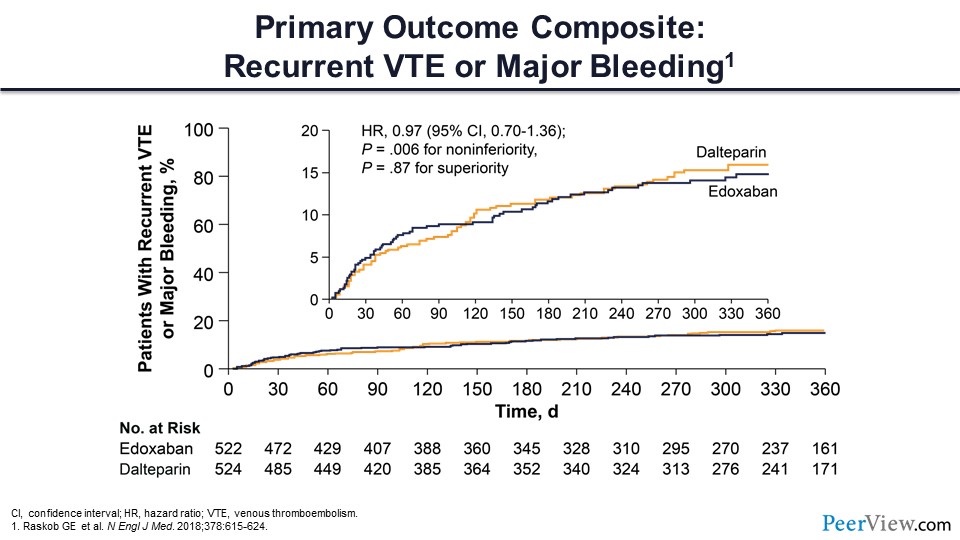

Slide 42

The figure in slide 42 shows that the primary outcome composite of recurrent VTE and major bleeding did not differ between these two treatment arms.

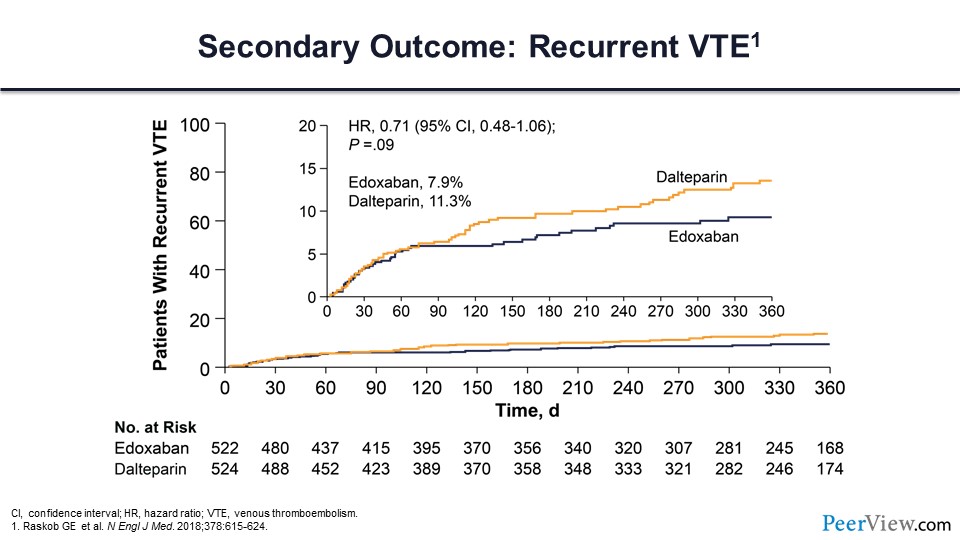

Slide 43

Recurrent VTE was 8% in those receiving edoxaban and 11% for those receiving dalteparin, which did not quite meet statistical significance.

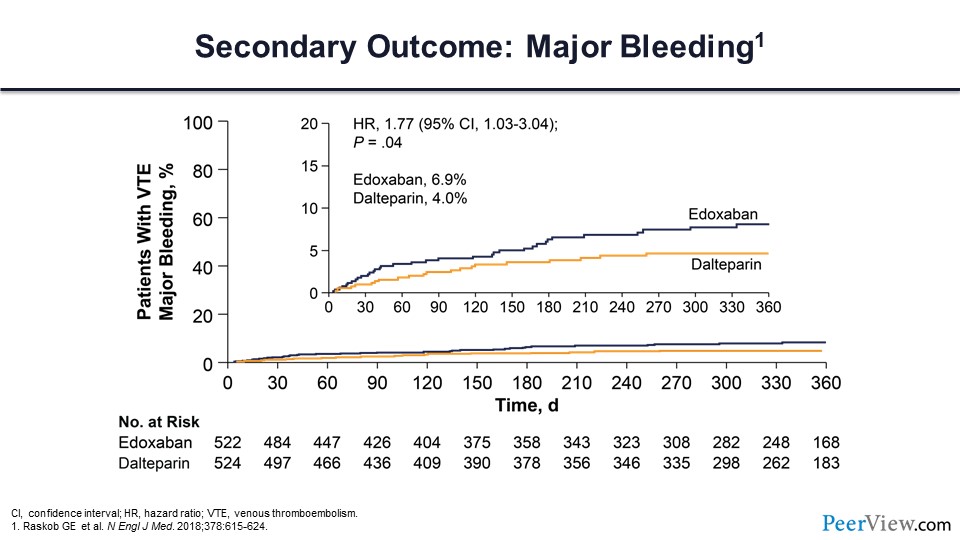

Slide 44

Major bleeding was higher in the edoxaban arm compared with the dalteparin arm, with a hazard ratio of 1.77.

Slide 45

This table reviews the specific VTE recurrence outcomes and the major bleeding outcomes. There were no confirmed fatal thrombotic events occurring in either arm. DVT was reduced in the edoxaban arm, as was symptomatic VT. From a major bleeding perspective, there were no fatal bleeds in the edoxaban arm and two in the dalteparin arm. The vast majority of the bleeding events occurred from an upper GI source.

Slide 46

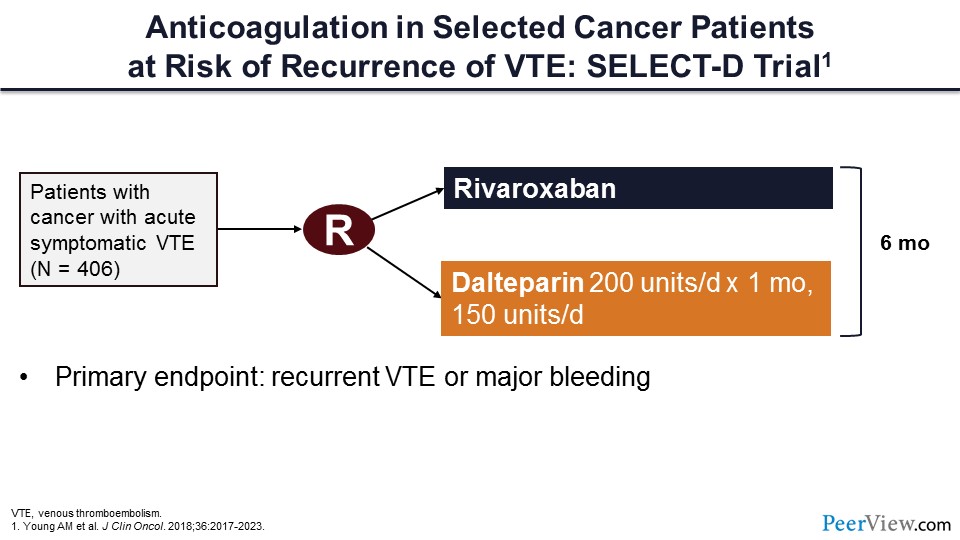

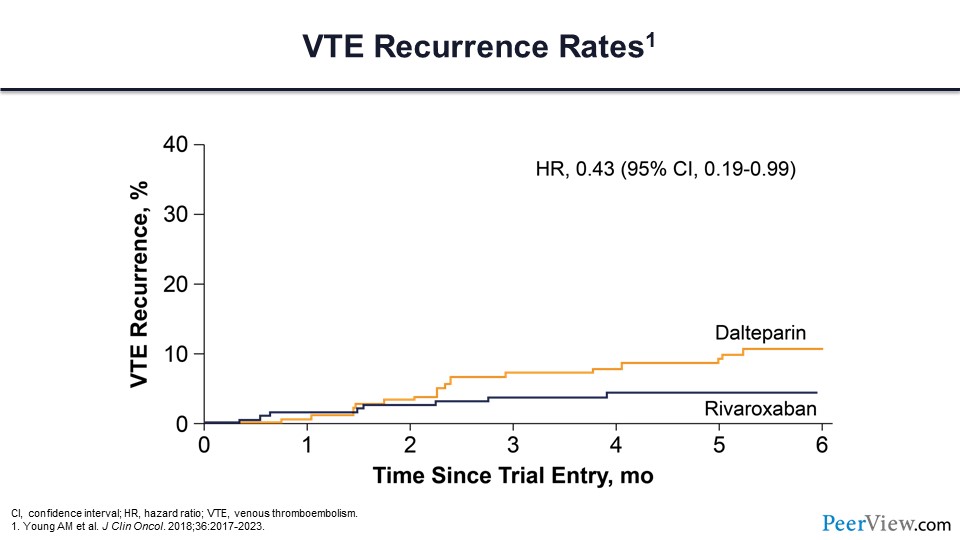

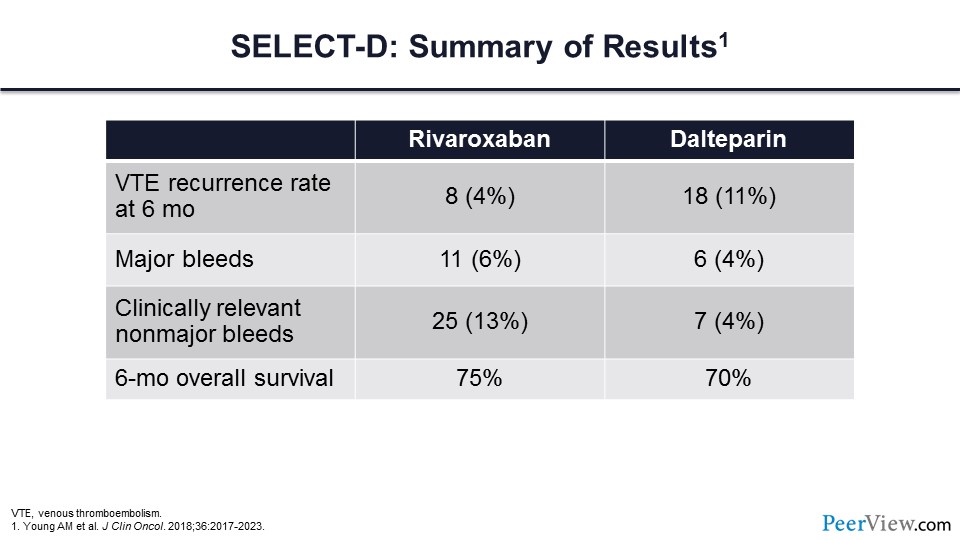

This trial is the SELECT-D trial, which compared rivaroxaban to dalteparin in more than 400 patients with cancer-associated acute symptomatic VTE.

Slide 47

The recurrent VTE rate was lower in those individuals who were assigned to the rivaroxaban arm.

Slide 48

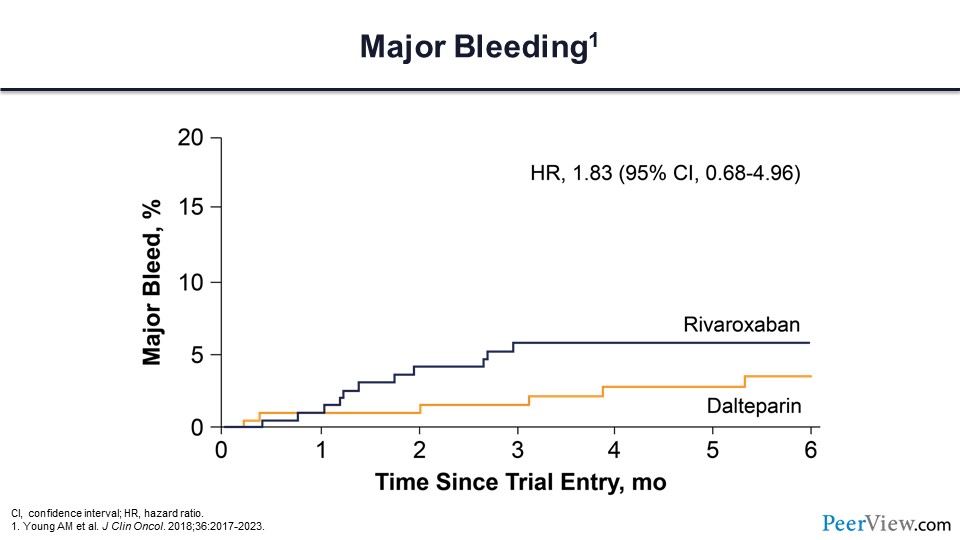

Major bleeding did not differ between these two treatment arms.

Slide 49

This table highlights the outcomes for the SELECT-D trial, and what you can see is that there was a significant reduction in VT events for patients assigned to rivaroxaban—4% compared with 11% in those receiving dalteparin. Major bleeding was slightly higher in the rivaroxaban arm, though it did not reach a statistically significant difference. However, clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was significantly higher in those patients assigned to the rivaroxaban arm. There was no difference in overall survival at 6 months.

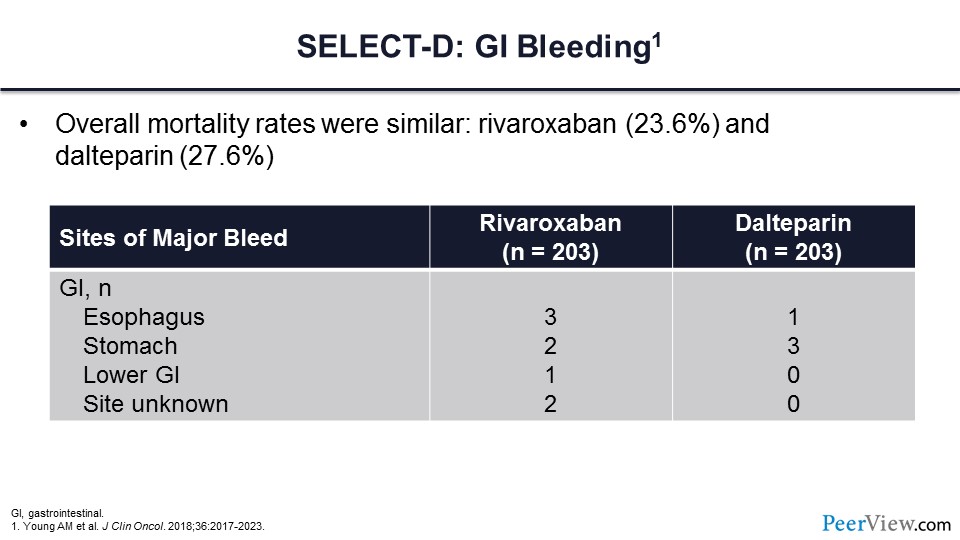

Slide 50

Like the Hokusai VTE Cancer trial, a major concern for the DOACs has been those individuals with GI malignancy and concerns regarding GI bleeding. In slide 50, you can see the rates of GI bleeding from upper intestinal tract and lower intestinal tract sources. Note also that the overall mortality was very similar between the rivaroxaban and dalteparin arms.

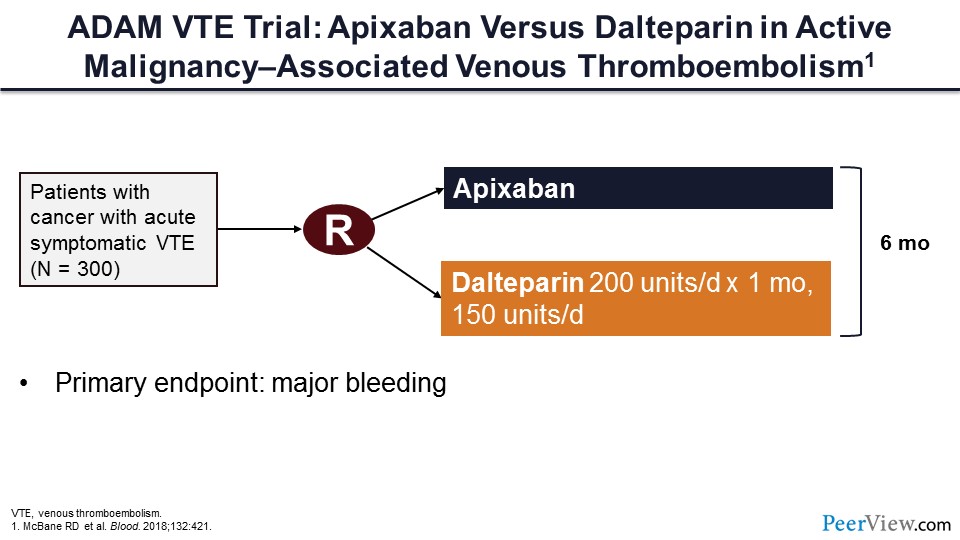

Slide 51

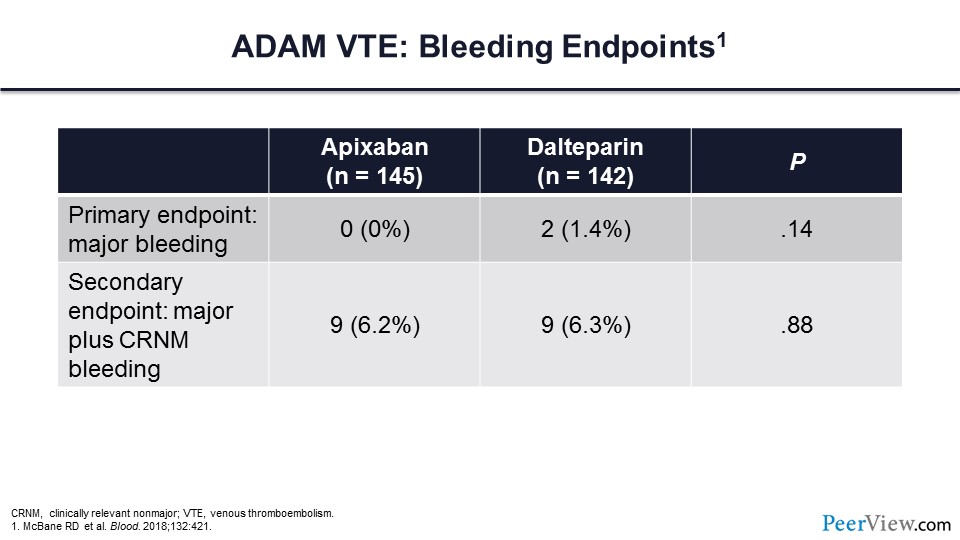

Lastly, this is the ADAM VTE trial, which compared apixaban with dalteparin for patients with cancer-associated VTE. In this trial, 300 patients were randomized to receive apixaban or dalteparin for 6 months. The primary endpoint of this trial was major bleeding.

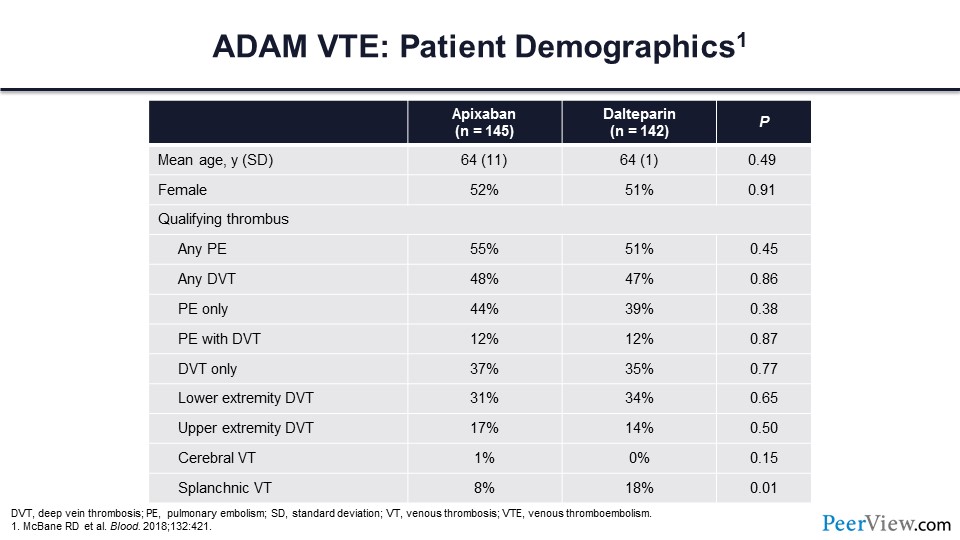

Slide 52

This table shows a difference between the ADAM trial and the other two trials that I talked about with regards to enrollment. In the ADAM trial, upper extremity DVT, splanchnic vein thrombosis, or cerebral vein thrombosis were all qualifying thrombotic events for trial enrollment.

Slide 53

In the ADAM trial, there were no major bleeding events in those individuals assigned to apixaban and very few major bleeds in those assigned to dalteparin. When the secondary composite endpoint of major bleeding plus clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was compared between the two arms, there was no difference.

Slide 54

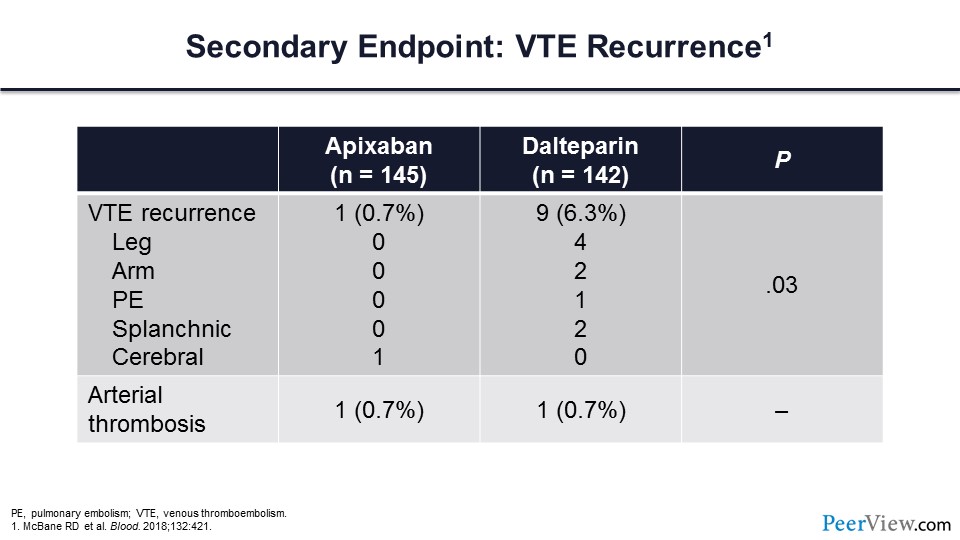

There were significantly fewer venous thrombotic recurrences in those patients assigned to apixaban relative to dalteparin. Here is the outcome for the secondary endpoint of VTE recurrence. Arterial thrombosis occurred in one patient for both arms.

Slide 55

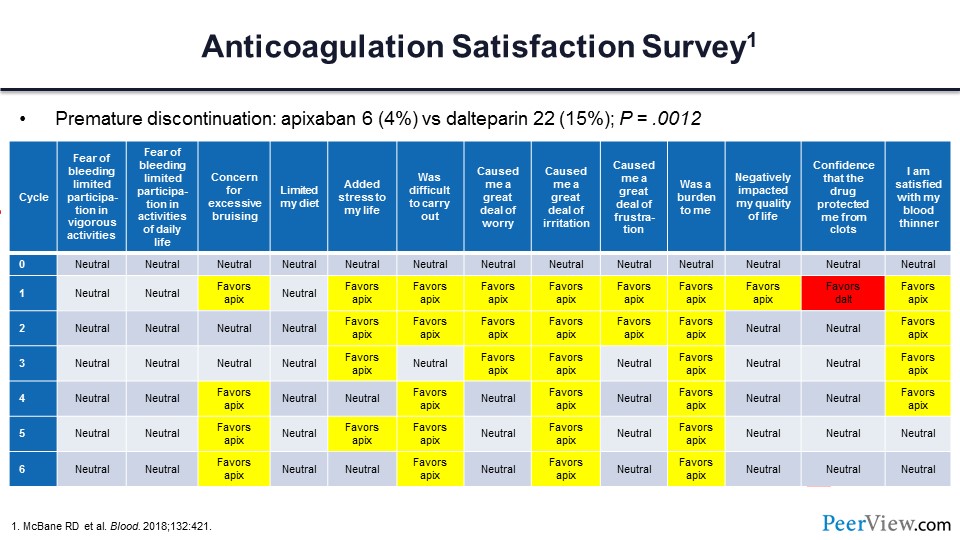

The ADAM investigators sought to determine the satisfaction of anticoagulation delivery for those patients assigned to receive either apixaban or dalteparin. To do this, each month patients filled out a modification of the Duke Anticoagulation Satisfaction Scale survey.

Slide 55 shows the questions across the top, and along the side the results for each of the months or cycles with which the patient filled out these surveys. I’ve color-coded the results, and for those boxes in yellow, the satisfaction survey favored apixaban significantly.

For the red boxes, the results favored dalteparin. The vast majority of patients preferred oral apixaban over parenteral dalteparin. Premature discontinuation rates were substantially lower in those individuals assigned to apixaban versus those assigned to the dalteparin arm.

Slide 56

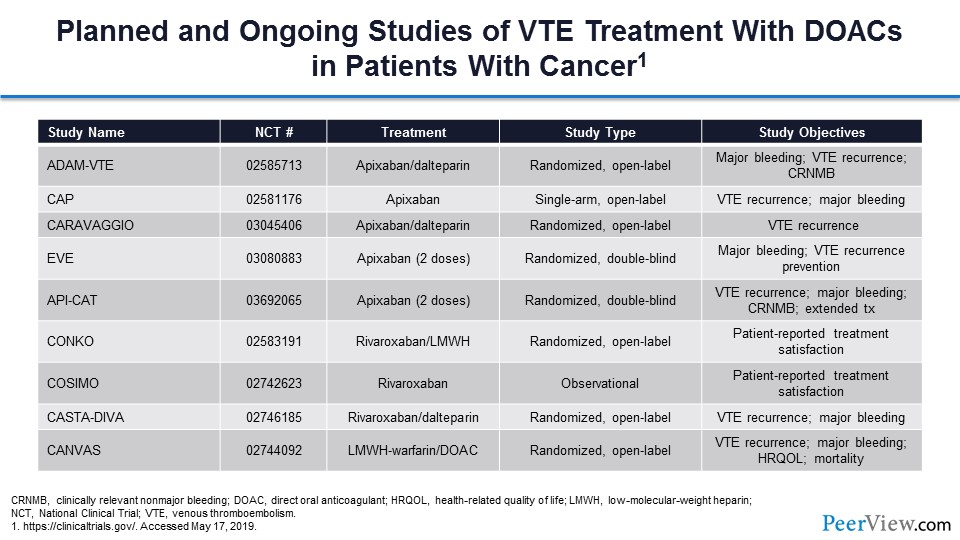

This table summarizes the current activity with respect to treatment trials in this space. You can see that there are a lot of trial investigations ongoing.

Slide 57

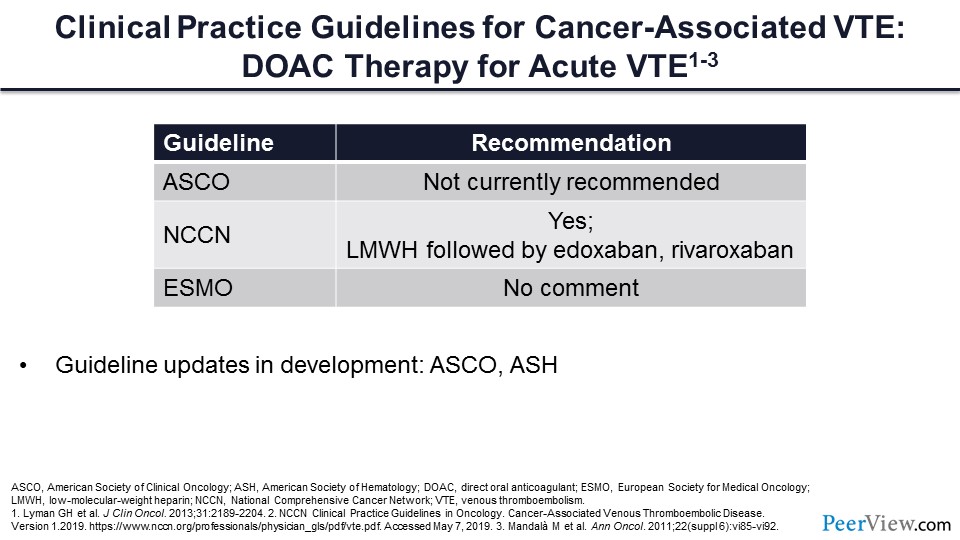

What do the guidelines say about the use of DOACs for the acute treatment of VTE? It is important to note that each of these guidelines are somewhat dated. The American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines would say that DOACs are not currently recommended. The updated National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, following the publication of Hokusai VTE and SELECT-D, have said that yes, these medications can be used for our patients with cancer-associated VT. Again, the European guidelines are somewhat dated, and have no comment regarding this question.

If we get back to our patient with pancreatic cancer and acute VTE, the question is, would we use a DOAC for that individual? And I think the answer is, based on the data that we have reviewed, that a DOAC would be very reasonable. The DOACs would reduce the need for parenteral injections, may increase the patient’s compliance and adherence to medications, and will certainly reduce the burden of management of the associated VT, along with the other variables related to cancer treatment. It’s important to note that these guidelines are anticipated to be updated to include comments on the DOACs in the very near future.

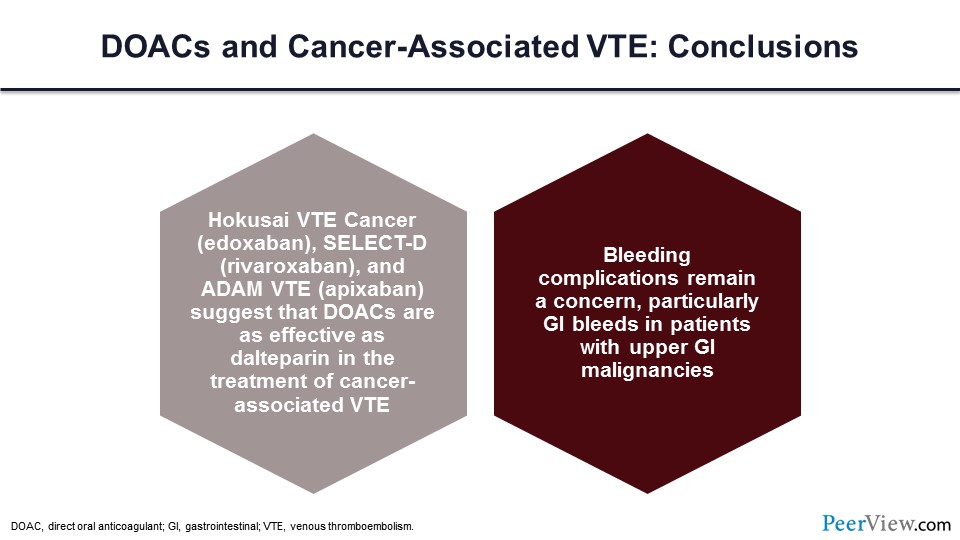

Slide 58

Based on the data that we’ve just reviewed, the new updated guidelines would support the use of a DOAC for the acute treatment of VTE in patients with cancer. Here are the new guidelines. In summary, the Hokusai VTE Cancer trial data, SELECT-D trial data, and ADAM VTE trial data all suggest that DOACs are as effective as dalteparin in the treatment of cancer-associated VTE. Bleeding complications remain a concern, particularly for those individuals with upper GI malignancies and the risk of GI bleeding.

Back Top