Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Case Studies in Chronic Idiopathic Constipation Management: Customizing Treatment Approaches in Community, Hospital, and Long-Term Care Settings

Introduction

Constipation is a highly prevalent problem in all practice settings, especially among older patients. In the hospital setting, constipation affects over 40% of patients,1 but is often evaluated and treated ineffectively.2 Among patients in both hospital and long-term care settings, contributing factors such as decreased mobility, medical comorbidities, postsurgical ileus, anesthetics, medications such as opioid analgesics, and lack of privacy for bowel management increase the risk of constipation. Among older patients, decreased muscle mass and impaired function of autonomic nerves may also contribute.3

Constipation, especially chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), can be difficult to manage effectively. The reasons for this are varied, including failure of patients to report symptoms, difficulty in pinpointing underlying causes of constipation, lack of effectiveness of many treatment approaches including both nonprescription and prescription therapies, and adverse effects that may limit the use of some available therapies.4

Pharmacists are a highly accessible group of healthcare professionals and are frequently consulted by patients about bowel irregularity issues.5 Many people may be more likely to ask a pharmacist for advice on constipation treatments, possibly because they regard physicians as "too busy" focusing on other matters relating to health. This program and case series reviews strategies for patient counseling and management of CIC in the community, hospital, and long-term care settings.

Burden of Constipation

Constipation is not just an annoyance, but an extremely common, difficult-to-treat, and often debilitating medical condition.6 Constipation affects up to 27% of the U.S. population, especially older individuals and women.7 This condition places a significant burden on the healthcare system, with up to 92,000 hospitalizations and 2.5 million physician visits attributed to constipation each year in the U.S.8 The incidence of constipation continues to rise with the aging of the population.9,10

Frequency and severity of constipation are often underestimated by both patients and healthcare professionals. Despite its prevalence and its effect on quality of life, CIC is often underdiagnosed or undertreated.7,11 People who suffer from constipation usually try to manage it initially with over-the-counter (OTC) therapies, many of which do not address the underlying cause and are ineffective in resolving the condition.12 Likewise, physicians and pharmacists may fail to consider the underlying causes when recommending treatment approaches for constipation.12-14 Pharmacists are often called upon to advise patients about bowel irregularity and/or gastrointestinal symptoms. In fact, many people are more likely to consult a pharmacist about issues they are too embarrassed to bring up with their doctors. In a 2019 Postgraduate Healthcare Education (PHE) survey of 192 pharmacists, 77% said they counsel or advise patients about constipation/ irritable bowel issues, with about one-third saying they do so "frequently" (about once a week).5

Definition and Symptoms of CIC

"Constipation" can refer to a range of symptoms including hard stool, excessive straining, infrequent bowel movements, bloating, and a sense of difficult or incomplete evacuation. Reduced stool frequency is not the best way to characterize constipation because it does not accurately reflect the patient's experience.15 Newer diagnostic criteria take this into account.16 Symptoms of CIC may overlap with those of other bowel disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). While the Rome III criteria considered IBS-C and CIC as separate entities, the revised Rome IV criteria allow patients to meet symptom criteria for either "functional constipation" or IBS-C. Rome IV Criteria for the Diagnosis of Functional Constipation are summarized in Table 1.15 The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Chronic Constipation Task Force has stated, "In some patients it may be difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate CC and IBS accurately and reliably."11

| Table 1. Rome IV Criteria for the Diagnosis of Functional Constipation15 |

- Onset of constipation symptoms at least 6 months before diagnosis

- Criteria met for the past 3 months:

I. Two or more criteria must be present:

a. Straining with > 25% of defecations

b. Lumpy or hard stools with > 25% of defecations

(Bristol stool form types 1 and 2)

c. Sensation of incomplete evacuation with > 25% of defecations

d. Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage with > 25% of defecations

e. Manual maneuvers required with > 25% of defecations

(digital evacuations, support for the pelvic floor)

f. Fewer than 3 spontaneous defecations per week

II. Loose stools are rare without administration of laxatives

III. Insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. |

| Adapted from: Lacy BE. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(4 Suppl):S55-S62. Open Access. |

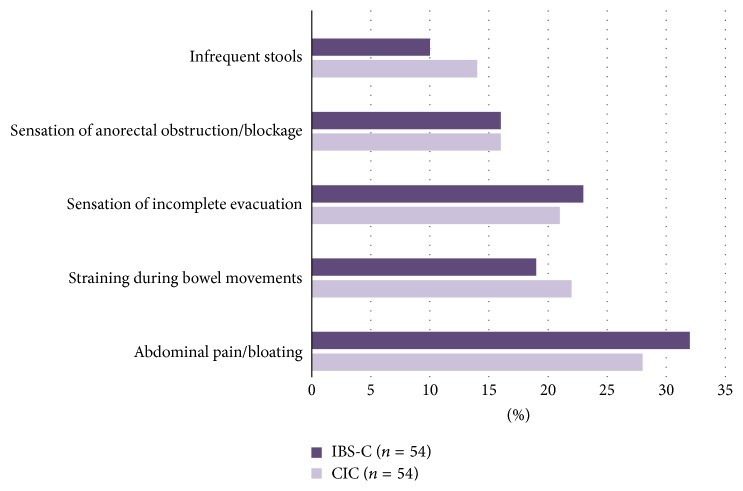

Many people with chronic constipation experience symptoms for many years without relief. In a web-based survey of 557 U.S. patients with constipation by Johanson and colleagues, the median duration of symptoms was 2.5 years, but over 20% of those surveyed had constipation for 10 years or longer.17 Most respondents reported straining during bowel movements, and nearly all respondents who experienced straining (90%) had this symptom for more than 6 years. Hard stool was reported by 71%, 84% of whom had this symptom for more than 6 years.17 In smaller survey of 108 physicians' perceptions of patient experience with CIC or IBS-C, abdominal pain and bloating were identified as the symptoms that most affects patients' quality of life, as shown in Figure 1.18

Figure 1. Physicians' Perceptions of Constipation Symptoms

Most Affecting Patients' Quality of Life18 |

|

| Definitions based on Rome III criteria separating IBS-C and CIC. Current Rome Criteria allow for overlap of these criteria. Reprinted from Tse Y, et al. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:8612189. Open Access. |

Mechanisms of Bowel Dysfunction

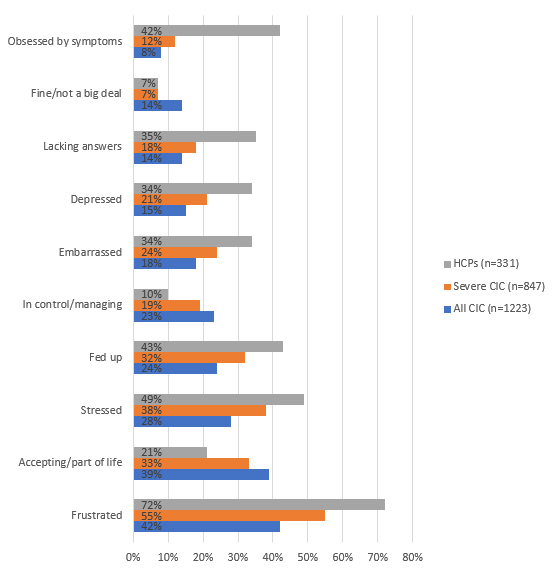

Causes of CIC include functional or slowed transit and outlet dysfunction.19 The most common scenario associated with CIC is normal gastrointestinal (GI) motility combined with hard stool. Slow transit constipation is characterized by a reduced frequency of bowel movements resulting from decreased GI motility.8 Constipation from outlet dysfunction is due to abnormalities of the pelvic floor and/or the anal sphincter. Some people may be affected by a combination of these issues. Many assume the cause of their bowel problems is solely dietary and will follow popular advice such as “eat more fiber” without exploring an underlying cause. As shown in Figure 2, a survey of 1,223 patients with CIC, 39% said they accepted constipation as "part of life."20

| Figure 2. Terms Used by Patients/HCPs to Describe CIC |

|

From the BURDEN-CIC survey of patients with CIC and healthcare professionals conducted

between June 2016 and January 2017. Data adapted from: Harris LA et al. Adv Ther. 2017;34:2661-2673. Open Access. HCP=healthcare provider; CIC=chronic idiopathic constipation |

People with constipation endure a variety of abdominal symptoms including pain, abdominal discomfort and bloating, and stomach cramping. Bowel symptoms include extended time between bowel movements; rectal pain, straining and incomplete evaluation; and hard, lumpy, or pellet-like stools.21 However, the burden of this condition is often underestimated, and constipation may be viewed as a mild annoyance. Effective patient education about constipation in the pharmacy setting requires awareness of patient risk groups and an understanding of the pathology of constipation.

Over-the-Counter Medications for Constipation

People with constipation often manage their condition primarily through the use of OTC agents.

Most people with IBS-C or CIC self-treat with OTC laxative preparations, but many receive only partial relief from this approach.12,13 OTC laxatives are ineffective in treating constipation with outlet dysfunction since they have little impact on the function of the pelvic floor or the anal sphincter.22 Patient surveys demonstrate a high degree of dissatisfaction with laxatives and constipation therapies in general. In the aforementioned survey of 557 U.S. patients by Johanson, most respondents had used (96%) or were using (72%) either OTC or prescription constipation treatment. However, nearly half were dissatisfied with their constipation treatment, 82% of whom were dissatisfied for efficacy-related reasons. Of those taking fiber at the time of the survey, 80% cited ineffective relief of bloating and 66% cited ineffective relief of symptoms.17 Of the patients taking OTC osmotic or stimulant laxatives, 67% cited ineffective relief of bloating and 60% cited ineffective symptom relief.17 Even among patients who do seek treatment from a medical practitioner, most do not receive a prescription therapy for constipation.

OTC medications with demonstrated effectiveness for treating constipation are summarized in Table 2 along with ACG 2014 classification for strength of recommendation and quality of evidence.23 These include fiber supplements, bulk-forming laxatives, and agents that stimulate motility. Several OTC agents commonly used for constipation do not have sufficient data to support their efficacy in CIC, including docusate, saline laxatives, and senna. Lactulose, while effective, has been shown to be inferior to polyethylene glycol in efficacy and tolerability and therefore is not the osmotic laxative of choice.15,23 In many cases, referral to a physician is appropriate for guideline-recommended assessments such as complete blood count and evaluation of comorbid medical conditions.23,24 Pharmacists can play an important role in this stage by taking a comprehensive and current medication history, providing patients with documentation to share with other providers, educating patients about contraindications and drug interactions among prescription and OTC medications, and recommending referral and evaluation by a physician when indicated.25,26 In hospital and long-term care settings, these roles are more comprehensive and may involve participation in daily bowel management plans, dosage recommendations, prevention of medication errors and drug interactions, and review of formulary selections.23,27

| Table 2. Over-the-Counter Medications for Constipation23 |

| Name (Brand if applicable) |

Mechanism |

ACG

Recommendation and Quality of Evidence for CIC |

Dosage Forms, Usual Adult Dosage |

Adverse Effects and Precautions |

Dietary fiber

Psyllium husk (Metamucil):

soluble fiber

Wheat dextrin (Benefiber):

soluble fiber

Bran: insoluble fiber |

Bulking agents; not digested in small intestine; delivered to colon |

May improve stool frequency

Rec: Strong

QOE: Low |

Many products available, including dissolvable powders, wafers, fiber capsules, and fiber capsules plus calcium.

Up to 30 g daily (increase gradually) |

Bloating, distension, flatulence, cramping (insoluble fiber > soluble fiber) |

Polyethylene glycol (PEG 3350)

(Miralax) |

Osmotic laxatives; attract and retain water in colon |

Improves symptoms

Rec: Strong

QOE: High |

17 g powder mixed with 4–8 ounces fluid once daily |

Flatulence, nausea, diarrhea

Use for no longer than 7 days without consulting physician |

| Senna (Senokot, Ex-Lax) |

Stimulant laxatives: Induce fluid secretion in colon; induce peristalsis |

Not listed by ACG under stimulant category as effective in CIC |

Sennosides 8.6 mg to 25mg, 1 to 2 tablets, once or twice daily. |

Diarrhea, cramping

Use for no more than 7 days |

| Bisacodyl (Dulcolax) |

Stimulant laxative: stimulates nerves to induce peristalsis in colon |

Effective

Rec: Strong

QOE: Moderate |

5 to 15 mg daily |

(Same adverse reactions/ precautions as above for other stimulants) |

Prescription Agents for Constipation

Prescription agents available for the management of constipation are summarized in Table 3.28-31 Specific patient populations may be appropriate candidates for linaclotide, plecanatide, lubiprostone, and 5-HT4 receptor agonists such as prucalopride.12,29,32-35

Linaclotide is a 14-amino acid peptide guanylate cyclase-C (GC-C) receptor agonist and intestinal secretagogue indicated for IBS-C and CIC. Activation of GC-C receptors by linaclotide is thought to result in increased levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), a key messenger in the regulation and secretion of intestinal fluid.36,37

Plecanatide is another agent in the GC-C receptor agonist class, indicated for CIC. Plecanatide is a more targeted, 16-amino acid peptide.38 In comparison with linaclotide, plecanatide is believed to replicate the activity of human uroguanylin in binding and activating GC-C receptors in the epithelial lining of the GI mucosa in a pH-sensitive manner, meaning that it can modulate within the changing pH environment of the intestines.38

Lubiprostone is a chloride channel-2 (CIC-2) activator that regulates fluid balance in the intestinal tract to increase fluid secretion and transit. This mechanism bypasses the antisecretory effect of opioids.31 This agent is indicated for CIC in adults, IBS-C and opioid-induced constipation.

The category of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 (5-HT4) receptor agonists consists of prokinetic agents capable of stimulating colonic motility and accelerating colonic transit.39 An older nonselective 5-HT4 receptor agonist, tegaserod, promotes intestinal motility to relieve constipation, but its lack of selectivity for the 5-HT4 receptor is potentially associated with ischemic cardiovascular events.40 While tegaserod was withdrawn from the U.S. market in 2007 due to these concerns, it returned to the market this year with an indication for treatment IBS-C in adult women under age 65 who do not have a history of cardiovascular ischemic events.41,42

A more highly selective 5-HT4 agent, prucalopride, is approved in the U.S for the management of CIC.43 Because of its high affinity for the 5-HT4 receptor, this agent has a more favorable safety and tolerability profile, even in elderly subjects who have stable cardiovascular disease.40 Clinical trials have shown significant improvements in bowel transit, bowel function, GI symptoms, and quality of life. Most studies were 12 weeks in duration but one study showed the benefit was maintained for up to 24 weeks.44,45

| Table 3. Prescription Medications for Chronic Idiopathic Constipation28-31 |

| Name (Brand) |

Indications |

Mechanism |

Dosage for CIC |

Adverse Effects and Precautions |

| Linaclotide (Linzess) |

CIC in adults, IBS-C in adults |

Guanylate cyclase-C (GC-C) agonist |

72 mcg or 145 mcg once daily |

Diarrhea (can be severe)

Take on empty stomach at least 30 minutes prior to first meal of the day.

Boxed warning for risk of severe dehydration in pediatric patients. Avoid use in patients < age 18. Contraindicated in patients < 6 yrs of age. |

| Plecanatide (Trulance) |

CIC in adults, IBS-C in adults |

Guanylate cyclase-C (GC-C) agonist |

3 mg once daily |

Diarrhea (rates < linaclotide in clinical trials)

Boxed warning for risk of severe dehydration in pediatric patients. Avoid use in patients <age 18. Contraindicated in patients < 6 yrs of age. |

| Lubiprostone (Amitiza) |

CIC in adults; OIC in adults; IBS-C in women ≥18 yrs |

Chloride channel-2 (CLC-2) activator |

24 mcg twice daily |

Nausea (less if taken with food), diarrhea

Adjust dose for hepatic impairment |

| Prucalopride (Motegrity) |

CIC in adults |

Serotonin 4- (5-HT4) receptor agonist |

2 mg once daily |

Headache, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea

Monitor patient for worsening depression/suicidal ideation

Renal impairment (CrCL ≤ 30 mL/min): 1 mg once daily |

| CIC=chronic idiopathic constipation; IBS-C=irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; OIC=opioid-induced constipation; CrCL=creatinine clearance |

Individualizing Therapy Across Practice Settings

Treatment for CIC must be individualized, and many patients receiving active treatment may remain constipated despite use of newer pharmacologic therapies. Several agents are associated with an increase in abdominal symptoms such as pain, diarrhea, and flatulence.46 It is essential for pharmacists in multiple practice settings to be aware of prescription and nonprescription treatments for CIC.

Community Pharmacy

In the community, people might not schedule a doctor visit solely for evaluation of constipation, so the pharmacist is often the first level of care as people seek temporary relief or OTC solutions at the pharmacy.47 Pharmacists who fill prescription therapies for CIC in the community need knowledge of these agents in order to counsel patients and answer questions about their use. These pharmacists need to expand their knowledge relating to the indications, mechanisms of action, dosing guidelines, and adverse effects/ precautions associated with these agents in order to effectively counsel patients.

Case 1. Counseling a Patient With Constipation in Community Pharmacy

AH is a 63-year-old Caucasian male at your community pharmacy, scanning the digestive health aisle. He has in his cart a bottle of prune juice and a box of senna. He informs you that he was here yesterday and bought a box of stool softeners, but has not yet had a bowel movement. His friend advised him to try prune juice and coffee, but AH thinks he is going to need something “stronger.” AH reports his last bowel movement was 3 days ago. He reports his stools are usually “little pebbles” and occur every three to five days. AH states that he has had difficulty passing stools for several years but figured it was a normal part of aging. AH admits to straining during bowel movements but denies any presence of blood.

Personal medical history includes hypertension, pre-diabetes, and osteoarthritis. His current medications include amlodipine 5mg daily, hydrochlorothiazide 25mg daily, calcium carbonate 500mg daily, cinnamon capsules daily and a multivitamin daily. His blood pressure at your pharmacy today was 131/78 mm Hg and he reports his last A1c was “a little over 6” when he saw his doctor two months ago. AH has been walking 5 to 6 times per week for the past 2 months after finding out he was pre-diabetic. He has also been drinking diabetic-friendly meal replacement shakes most days for lunch.

You counsel AH that stool softeners like docusate may take 1 to 3 days to work. These medications primarily lubricate stool but do not provide bulk. They also require adequate water intake. While docusate is safe to take, it has not been proven to be very effective for chronic constipation. AH may benefit from fiber supplementation. He may have relatively low intake of dietary fiber, since he is consuming meal-replacement shakes. Given that he has a history of hypertension and is concerned about his pre-diabetes, you counsel the patient on caffeine and fruit juice intake. With respect to the senna, you advise AH that senna is a stimulant laxative which may not be appropriate for him to take long term. (Data supporting the efficacy of senna as a stimulant laxative is less-robust than that for bisacodyl.) Since he reported that his constipation has been ongoing for several years, he may want to consult his doctor for evaluation of underlying causes.

You also tell AH that some medications, including his blood pressure medications and supplements containing iron and calcium, may increase his risk of constipation. Sometimes, protein shakes may worsen constipation. You stress to him that he should not stop any of his prescribed medications unless directed to do so by his physician. In the meantime, you recommend AH consider a bulk-forming laxative. You explain to him that these agents are very safe and work by increasing water and fecal mass in his stool. You instruct him to drink adequate water and warn him that may take a few days to work. You also tell him that he may have some initial bloating or discomfort in the beginning and if he does not have a bowel movement in a few days, he should reach out to his physician. |

Constipation in the Hospital Setting

Constipation among hospitalized patients is common, affecting an estimated 40% of hospital inpatients and at least 50% of inpatients over age 65.1,2 Hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of constipation increased from about 21,000 patients in 1997 to over 48,000 patients in 2010, based on a study using the National Inpatient Sample Database .48

Among the reasons for increased rates in this population include reduced oral food intake due to illness, dehydration, delirium, dementia, immobility, and use of medications such as opioid analgesics. Lack of privacy for adequate bowel movement in the hospital can also be a factor. Despite the prevalence of constipation in the hospital setting, patients may not be assessed regularly enough for acute constipation.2 Some authors describe overuse of laxatives and docusate in hospitals coupled with lack of review for the appropriateness of these treatments.2

For the hospital-based pharmacist, advising on constipation management may involve establishing, overseeing, or consulting on individualized bowel care plans.49 Pharmacists who counsel patients in hospital setting need to be aware of the patient's regular medications as well as those used during the hospital stay, as use of multiple medications may affect bowel behavior (Table 4).50-53 Immobility, as well as surgery and other medical procedures, may affect bowel function. Some of these issues are discussed in Case 2 involving a young adult female patient admitted for severe abdominal pain.

| Table 4. Medications Causing or Exacerbating Constipation50-55 |

- Antidepressants (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors)

- Metals (e.g., iron, bismuth)

- Anticholinergics (e.g., diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl)

- Opioids (e.g., codeine, morphine)

- Antacids (e.g., aluminum, calcium compounds)

- Calcium channel blockers (e.g., verapamil)

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen, diclofenac)

- Antipsychotic medications (e.g., clozapine)

- Cholestyramine

- Stimulant laxatives, when used long term*

- Inadequate thyroid hormone supplementation (levothyroxine)

|

| *Chronic use of laxatives can become habituating and lead to dilated atonic laxative colon. This necessitates increasing laxative use with decreasing efficacy.55 |

Case 2. Management of a Patient With Constipation in an Inpatient Setting

FD is a 28-year-old Hispanic female who presented to your ED with several episodes of nausea and vomiting over the past 24 hours. She also complained that she has had several days of excruciating abdominal pain. The pain seems to be worse after eating although she doesn’t have much of an appetite. She denies the possibility of pregnancy, has no history of abdominal surgeries, and is not taking anything except her birth control and PRN ibuprofen for menstrual cramps.

| BP |

120/84 |

| HR |

100 |

| Temp |

99.1 |

| Resp |

18 |

| Height |

1.702m |

| Weight |

65kg |

| LMP |

7 days ago |

| Family History |

Father had MI at age 59, mother has RA; no known history of colorectal cancer |

Kidney/ureter/

bladder x-ray (KUB) |

Significant for stool impaction, no perforation or wall abnormalities seen |

| Labs |

WNL except for slight electrolyte deficiencies |

An NG tube is placed after the patient has ongoing emesis after admission and is stable during her initial GI consult.

Upon evaluation by the GI team, FD has not had a bowel movement for eight days. FD tried to self-treat her constipation and took multiple OTC products prior to her admission. She does not recall the names of the products but thinks two of them were stimulant laxatives pills, one was a tasteless powder she mixed with a glass of water, and one was a clear looking suppository. FD reports that she usually has trouble passing bowel movements and it has been ongoing for a while. She says her bowel movements are “normal” but she often has to strain and feels she has incomplete evacuation. FD saw a doctor over a year ago for her chronic constipation and took a combination of polyethylene glycol (PEG/Miralax) and bisacodyl for a few months. She felt these medications did not help her constipation so she did not return to her doctor and she stopped the medications. She has since been managing her constipation by eating a high fiber diet.

The GI fellow orders saline enemas for nursing to administer, PEG now and prucalopride 2mg daily. These orders come to your verification queue but prucalopride is not on your hospital formulary. You page the GI fellow to discuss the orders for PEG and prucalopride. Given the patient’s electrolytes and current stool impaction, you suggest a trial of PEG 3350 which has been shown to be non-inferior to prucalopride and is on your hospital formulary.56

You also inform the GI fellow that linaclotide is also on the formulary and can be given via NG tube if necessary. He agrees with your recommendations and orders linaclotide. Lastly, you refer the patient to your transitions of care colleagues for assistance in prior authorization approval for linaclotide or similar agent upon discharge from your hospital. |

CIC in Long-term Care Settings

In the long-term care setting, constipation is especially common and contributes to multiple complications in patient care. Constipation prevalence spikes considerably at age 70 and up.57 And, constipation is two to three times more likely to occur in women, who make up the majority of long-term care residents.58 As many as 72% of patients in long-term care facilities experience constipation, and over 69% of these use laxatives both regularly and on demand.59 Secondary or iatrogenic constipation becomes a more important concern in older patients, in association with comorbid health conditions such as thyroid disorders, Parkinson's disease, diabetes, and many conditions that limit exercise and ambulation.57 Comorbid psychiatric disease makes constipation much harder to manage.60

Among long-term care residents, constipation may manifest as dehydration or nausea and may result in fecal impaction or bowel obstruction. This can result in delirium, increased risk of hospitalization and length of stay in the hospital, and increased morbidity and mortality.61 At the same time, over-treatment with laxatives can result in iatrogenic diarrhea, leading to dehydration, delirium, and even false positive diagnosis of conditions such as clostridium difficile (also increasing risk of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality).61

Bowel function may worsen as the long-term care resident's health declines. Patient groups especially at risk for persistent constipation are those with cancer or other advanced, progressive illness, especially if they are taking opioid analgesics. This is a primary reason why constipation is reported in over 42% of patients in palliative care settings. In these settings, constipation is the most frequent somatic symptom aside from fatigue, pain, and cachexia.62

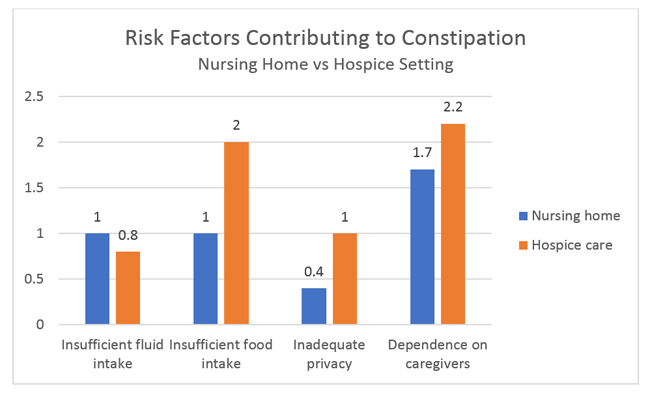

In a 2018 study comparing 51 patients on hospice care and 49 regular nursing home residents, constipation was identified in 80% of the palliative care patients and 59% of nursing home residents. Factors contributing to constipation in these settings are shown in Figure 3.62 In the hospice setting, food intake and privacy were associated with significantly greater risk compared with nursing homes.

| Figure 3. Risk Factors Contributing to Constipation: Nursing Home vs Hospice62 |

|

| Comparison of risk factors (mean intensity) for constipation in nursing home and hospice settings. Source: Dzierżanowski T. Prz Gastroenterol. 2018;13(4):299-304. Open Access License 4.0 |

Case 3 reviews some of these issues in the management of a patient with multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy.

Case 3. Counseling a Patient With Constipation in a Long-Term Care Setting

CO is a 73-year-old woman who is transferred to your long term care facility after a hip replacement. She has multiple longstanding comorbid conditions including CVA in 2015, hypertension x 30 years, rheumatoid arthritis x 50 years, and uveitis x 15 years. She was diagnosed with CIC last year. Prior to her hip fracture, she was relatively non-ambulatory. She also has ill-fitting dentures which makes it difficult for her to eat and may have contributed to her 8-pound weight loss prior to her hip fracture. Her diet consists of mostly blended and thickened foods as she has mild dysphagia from her CVA. She can swallow her pills without issue. Vitals and laboratory have been WNL post discharge. Last bowel movement was 2 days ago. CO reports she usually has a bowel movement every 3 to 4 days, but after surgery this interval has increased to every 4 to 5 days. CO is requesting something stronger for her worsening constipation.

CO’s medications include:

| Aspirin |

81mg PO daily |

| Adalimumab |

40mg SC every other week

(on hold s/p hip replacement for wound healing x 2 more weeks per surgery) |

| Acetaminophen/hydrocodone bitartrate |

One 325 mg/5mg tablet PO every 6 hours PRN (patient takes 1 per day prior to PT and sometimes a second dose before bed; prior to hip replacement, she was taking 1 tablet per day for RA associated pain) |

| Atenolol/chlorthalidone |

50mg/ 25mg daily |

| Baclofen |

5mg PO three times daily |

| Docusate |

250mg PO two times daily |

| Folic acid |

5mg PO every Friday |

| Methotrexate |

12.5mg PO every Monday |

| Senna |

8.6mg PO two times daily |

The long-term care facility is reviewing CO’s transfer. They ask for your input on her multiple medications and ask if plecanatide 3mg daily would be appropriate for her bowel regimen. They would also like to know if they should reach out to the patient’s primary care provider for any other medication-related issues, and if there are any food-drug interactions they should take into consideration.

After reviewing CO’s medications, you respond that plecanatide would be an appropriate therapy to initiate for this patient, especially since it only requires once-daily dosing. You also recommend that they consider lubiprostone (24 mcg twice daily), which has an indication for both CIC and opioid induced constipation since CO takes acetaminophen/hydrocodone on a regular basis. In addition, you discuss the possibility that some of CO’s other medications may be contributing to her chronic constipation. These include her atenolol/chlorthalidone as well as her baclofen. Unfortunately, the patient’s dietary modifications may also contribute to her constipation since she is likely having little fiber, low fluid intake, and low caloric intake. Lack of ambulation may also contribute to her constipation. There are no food-drug interactions with her current medications but the patient may benefit from a nutrition consult while she is recovering at your facility. |

Conclusion

In any pharmacy practice setting, it is likely that CIC is affecting a large proportion of the patient population. Most patients attempt to manage CIC on their own using OTC remedies, or just suffer in silence assuming that it is an inevitable consequence of aging. Left untreated, CIC can lead to poor quality of life and complications such as hemorrhoids and fecal impaction. Diagnosis and treatment are often hampered by patients' reluctance to talk about their bowel problems. In the hospital and long-term care settings, patients are often not evaluated on an individualized basis for constipation and may be subject to over-treatment with agents such as docusate. In older patients across all practice settings, polypharmacy increases the risk of constipation. Pharmacists involved in counseling and advising in the treatment of patients with constipation in the community, hospital, and long-term care settings should apply an individualized approach to management.

References

- Noiesen E, Trosborg I, Bager L, et al. Constipation--prevalence and incidence among medical patients acutely admitted to hospital with a medical condition. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(15-16):2295-2302.

- Fakheri RJ, Volpicelli FM. Things We Do for No Reason: Prescribing Docusate for Constipation in Hospitalized Adults. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):110-113.

- De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, et al. Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:130.

- Quigley EM, Neshatian L. Advancing treatment options for chronic idiopathic constipation. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17(4):501-511.

- Postgraduate Healthcare Education (PHE). Pharmacist survey. June 2019. Data on file.

- Camilleri M, Ford AC, Mawe GM, et al. Chronic constipation. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17095.

- Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):750-759.

- Jamshed N, Lee ZE, Olden KW. Diagnostic approach to chronic constipation in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(3):299-306.

- Sanchez MI, Bercik P. Epidemiology and burden of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25 Suppl B:11B-15B.

- Vazquez Roque M, Bouras EP. Epidemiology and management of chronic constipation in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:919-930.

- Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100 Suppl 1:S5-S21.

- Bassotti G, Blandizzi C. Understanding and treating refractory constipation. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2014;5(2):77-85.

- Ryu HS, Choi SC. Recent Updates on the Treatment of Constipation. Intest Res. 2015;13(4):297-305.

- Storr M. Chronic constipation: current management and challenges. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25 Suppl B:5B-6B.

- Lacy BE. Update on the management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(4 Suppl):S55-s62.

- Simren M, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Update on Rome IV Criteria for Colorectal Disorders: Implications for Clinical Practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(4):15.

- Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(5):599-608.

- Tse Y, Armstrong D, Andrews CN, et al. Treatment Algorithm for Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Derived from a Canadian National Survey and Needs Assessment on Choices of Therapeutic Agents. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:8612189.

- Andrews CN, Storr M. The pathophysiology of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25 Suppl B:16B-21B.

- Harris LA, Horn J, Kissous-Hunt M, et al. The Better Understanding and Recognition of the Disconnects, Experiences, and Needs of Patients with Chronic Idiopathic Constipation (BURDEN-CIC) Study: Results of an Online Questionnaire. Adv Ther. 2017;34(12):2661-2673.

- Heidelbaugh JJ, Stelwagon M, Miller SA, et al. The spectrum of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: US survey assessing symptoms, care seeking, and disease burden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(4):580-587.

- American Gastroenterological Association. Medical Position Statement on Constipation. Gasteroenterol. 2013;144(1):211-217.

- Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109 Suppl 1:S2-26; quiz S27.

- Serra J, Mascort-Roca J, Marzo-Castillejo M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of constipation in adults. Part 1: Definition, aetiology and clinical manifestations. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40(3):132-141.

- Eoff JC. Optimal treatment of chronic constipation in managed care: review and roundtable discussion. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(9 Suppl A):1-15.

- Borgsteede SD, Rhodius CA, De Smet PA, et al. The use of opioids at the end of life: knowledge level of pharmacists and cooperation with physicians. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(1):79-89.

- Serra J, Mascort-Roca J, Marzo-Castillejo M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of constipation in adults. Part 2: Diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40(4):303-316.

- Trulance (plecanatide) Package Insert. Bridgewater, NJ: Salix Pharmaceuticals. May 2019.

- Motegrity (prucalopride) Package Insert. Lexington, MA: Shire US. Dec 2018.

- Linzess (linaclotide) Package Insert. Cambridge, MA: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. Oct 2018.

- Amitiza (lubiprostone) Package Insert. Bedminster, NJ: Sucampo Pharma Americas. 2017.

- Rey E, Mearin F, Alcedo J, et al. Optimizing the Use of Linaclotide in Patients with Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Expert Consensus Report. Adv Ther. 2017.

- Ford AC, Suares NC. Effect of laxatives and pharmacological therapies in chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2011;60(2):209-218.

- Al-Salama ZT, Syed YY. Plecanatide: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2017.

- Schey R, Rao SS. Lubiprostone for the treatment of adults with constipation and irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(6):1619-1625.

- Sood R, Ford AC. Linaclotide: new mechanisms and new promise for treatment in constipation and irritable bowel syndrome. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2013;4(6):268-276.

- Bharucha AE, Linden DR. Linaclotide - a secretagogue and antihyperalgesic agent - what next? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(3):227-231.

- Rao SSC. Plecanatide: a new guanylate cyclase agonist for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818777945.

- Tack J, Camilleri M, Chang L, et al. Systematic review: cardiovascular safety profile of 5-HT(4) agonists developed for gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(7):745-767.

- Omer A, Quigley EMM. An update on prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10(11):877-887.

- Zelnorm (tegaserod) Package Insert. Louisville, KY: Sloan Pharma. 2019.

- Madia VN, Messore A, Saccoliti F, et al. Tegaserod for the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2019.

- Motegrity (prucalopride) Prescribing Information. Lexington, MA; Shire LLC; 2018.

- Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, et al. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation--a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):315-328.

- Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(22):2344-2354.

- Sonu I, Triadafilopoulos G, Gardner JD. Persistent constipation and abdominal adverse events with newer treatments for constipation. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3(1):e000094.

- Horn JR, Mantione MM, Johanson JF. OTC polyethylene glycol 3350 and pharmacists' role in managing constipation. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52(3):372-380.

- Sethi S, Mikami S, Leclair J, et al. Inpatient burden of constipation in the United States: an analysis of national trends in the United States from 1997 to 2010. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(2):250-256.

- Amatya B, Elmalik A, Lowe M, et al. Evaluation of the structured bowel management program in inpatient rehabilitation: a prospective study. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(6):544-551.

- Costilla VC, Foxx-Orenstein AE. Constipation: understanding mechanisms and management. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(1):107-115.

- Every-Palmer S, Newton-Howes G, Clarke MJ. Pharmacological treatment for antipsychotic-related constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:Cd011128.

- Rao SS, Rattanakovit K, Patcharatrakul T. Diagnosis and management of chronic constipation in adults. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(5):295-305.

- Sharma A, Rao S. Constipation: Pathophysiology and Current Therapeutic Approaches. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;239:59-74.

- Questran (cholestyramine for oral suspension) Package Insert. Chestnut Ridge, NY: Par Pharmaceutical. 2019.

- Noergaard M, Traerup Andersen J, Jimenez-Solem E, et al. Long term treatment with stimulant laxatives - clinical evidence for effectiveness and safety? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(1):27-34.

- Cinca R, Chera D, Gruss HJ, et al. Randomised clinical trial: macrogol/PEG 3350+electrolytes versus prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation -- a comparison in a controlled environment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(9):876-886.

- Gallagher PF, O'Mahony D, Quigley EM. Management of chronic constipation in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(10):807-821.

- Mugie SM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25(1):3-18.

- Fosnes GS, Lydersen S, Farup PG. Drugs and constipation in elderly in nursing homes: what is the relation? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:290231.

- Cusack S, Rose Day M, Wills T, et al. Older people and laxative use: comparison between community and long-term care settings. Br J Nurs. 2012;21(12):711-714, 716-717.

- Linton A. Improving management of constipation in an inpatient setting using a care bundle. BMJ Qual Improve Rep. 2014;1-4. .

- Dzierzanowski T, Cialkowska-Rysz A. The occurrence and risk factors of constipation in inpatient palliative care unit patients vs. nursing home residents. Prz Gastroenterol. 2018;13(4):299-304.

Back Top