Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Evidence for Change: Optimizing Outcomes in Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema

A Conversations in CareTM CME/CE Supplement for Managed Health Care Executives

| Definition of Abbreviations and Terms |

|

AMD = age-related macular degeneration

ASRS = American Society of Retina Specialists

CST = central subfield thickness

DME = diabetic macular edema

DR = diabetic retinopathy

|

NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy

OCT = optical coherence tomography

PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy

VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor

VA = visual acuity

|

Introduction

|

Diabetic retinopathy is a potentially progressive microvascular complication of diabetes, in which there is damage to small blood vessels in the retina. The damaged vessels can develop microaneurysms and become occluded, causing retinal ischemia that leads to production of VEGF. VEGF causes the microaneurysms to leak and stimulates neovascularization, which is the growth of abnormal new vessels that are particularly prone to leak fluid and bleed. With the development of neovascularization, the disease progresses from NPDR to PDR.

Diabetic macular edema develops when the leaking blood vessels are located in the macula. Diabetic macular edema is the most common cause of vision loss for patients with DR, and it can occur in both the nonproliferative and proliferative stages. Swelling of the macula causes blurring of central vision that is assessed by testing VA. Swelling of the macula is measured using OCT to measure CST. The macula is considered “dry” if CST is ≤ 250 µm.

In its earliest stages, NPDR is asymptomatic, but pathology that develops with NPDR can also cause decreased vision. Proliferative DR can lead to profound loss of vision as a result of complications that include bleeding into the vitreous cavity in the back of the eye, retinal scarring, and retinal detachment.

|

Diabetes is a growing epidemic that has been projected to affect 43 million people in the United States at present and is projected to affect 55 million by 2030.1 Diabetic retinopathy is a common microvascular complication of diabetes and the leading cause of vision loss in working-age adults.2 An estimated one-third of people with diabetes have DR, approximately one-third of whom have a vision-threatening form, defined as severe NPDR, PDR, or DME.

Anti-VEGF therapy is regarded as the initial treatment choice for center-involved DME; it has been shown to promote regression of DR and to prevent its progression in patients at high risk of developing sight-threatening disease.3-5 The available options for anti-VEGF therapy differ in efficacy, safety, and administration schedules. The frequency of return visits is an important consideration for patients with diabetes who are often still working and under the care of multiple specialists to manage comorbid conditions.

Individualization of treatment favors the ability to provide each patient with the best outcome. Retina specialists are an invaluable resource for providing managed health care executives the latest evidence, according to which they can create appropriate models to cover treatment for DR and DME. At the same time, it is helpful if retina specialists can understand the payers’ perspectives and needs in designing plans on a population-wide basis. Equipped with this information, payers and providers can collaborate to identify strategies that promote value and quality outcomes.

Anti-VEGF Therapy Costs and Goals

Dr Owens: Aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab are the anti-VEGF agents used for the treatment of DR and DME. Bevacizumab is used off-label as a compounded product. Compared with bevacizumab, the 2 anti-VEGF agents that are approved for the treatment of DR and DME—namely, aflibercept and ranibizumab—are very expensive.6,7 Use of aflibercept and ranibizumab in ophthalmology accounts for a significant proportion of Medicare Part B drug spending.8 In addition, their cost is garnering greater attention from payers as the ophthalmic indications for anti-VEGF therapy expand.

There can be a divide between clinicians and payers regarding treatment decisions because these 2 groups are approaching the task from different perspectives and with different goals. Clinicians choose treatment according to what they believe will be best for an individual. The payer’s policy is developed according to what seems appropriate for the overall population, but that might not match the needs of a particular individual.

Dr Pieramici: Dr Owens’s points are well taken. If clinicians and payers are going to work successfully together for the benefit of patients, it is important that each group understands the factors that drive the other’s decisions. As we talk about choice of anti-VEGF agents for diabetic eye disease and the cost of providing this treatment, it is also important to consider that the cost will continue to rise because the number of people with diabetes is increasing,1 and because indications for anti-VEGF treatment of diabetes-related eye disease have expanded to include DR; therefore, more patients with diabetes may be considered for anti-VEGF treatment.1,9,10 This growing economic burden creates further impetus to identify strategies for providing care that is cost effective overall and simultaneously optimal for individuals.

All physicians want the freedom to make decisions for each patient—on the basis of their expertise and clinical judgment—that are in that patient’s best interest. In terms of anti-VEGF treatment for diabetic eye disease, the decision involves autonomy both for choosing initial therapy and for switching to another agent when it is deemed appropriate by the clinical course. No 2 patients are the same; there is variability among patients in clinical features at presentation that are relevant for treatment selection. Patients also differ in their response to a given therapy and whether they might develop tolerance or tachyphylaxis over time; these are issues that drive decisions for switching treatment. Additionally, social and economic factors may drive decisions for individual patients.

Clinical trial evidence has shown that in certain clinical situations, patients with DME are likely to achieve better functional and anatomic improvement if treated with an anti-VEGF agent other than bevacizumab.11,12 Therefore, step-therapy policies mandating the initial use of bevacizumab and continued use for a certain duration before a switch is allowed make it challenging for retina specialists to provide optimal care for patients needing anti-VEGF therapy for diabetic eye disease.

Differentiating Anti-VEGF Agents

Dr Wong: Because health plan executives are managing a patient population and not individuals, they are interested in whether or not there are clinically relevant differences among the available anti-VEGF agents, and if so, are there ways to predict who will benefit from a particular medication. The executives first look at the evidence base for developing policy, and then to expert consensus opinion.

What is the evidence that shows a difference in efficacy between bevacizumab and the other anti-VEGF agents?

Dr Shah: I am going to focus on DME because that is by far the most common indication today for anti-VEGF treatment in patients with diabetic eye disease. Although we may focus on DME, it is important to note that both ranibizumab and aflibercept have recently received US Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for the treatment of DR, even in cases without DME.9,10 The approval for ranibizumab was based on evidence showing that it promoted regression of DR4,5; evidence for aflibercept showed that it promoted regression of DR and reduced progression of nonproliferative to proliferative disease.3 It is my impression that many retina specialists are not treating DR unless DME is also present. This may be a function of their ensuring that the risk:reward ratio is favorable for patients to undergo an intraocular injection, but I believe an additional reason is awareness of the cost of anti-VEGF therapy, which retina specialists are also trying to contain.

For DME, the most pivotal data demonstrating differences in outcomes using the 3 anti-VEGF agents come from the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Protocol T.11 The findings of this study resulted in a sizable shift in the use of anti-VEGF medications.

Protocol T randomized 660 patients with center-involved DME and VA of 20/32 to 20/320 to receive intravitreal aflibercept 2 mg, bevacizumab 1.25 mg, or ranibizumab 0.3 mg.11 Repeat injections were given as needed as often as every 4 weeks according to the protocol-specified algorithm, and eyes with residual edema at 6 months received focal laser unless the investigator felt it was unsafe.

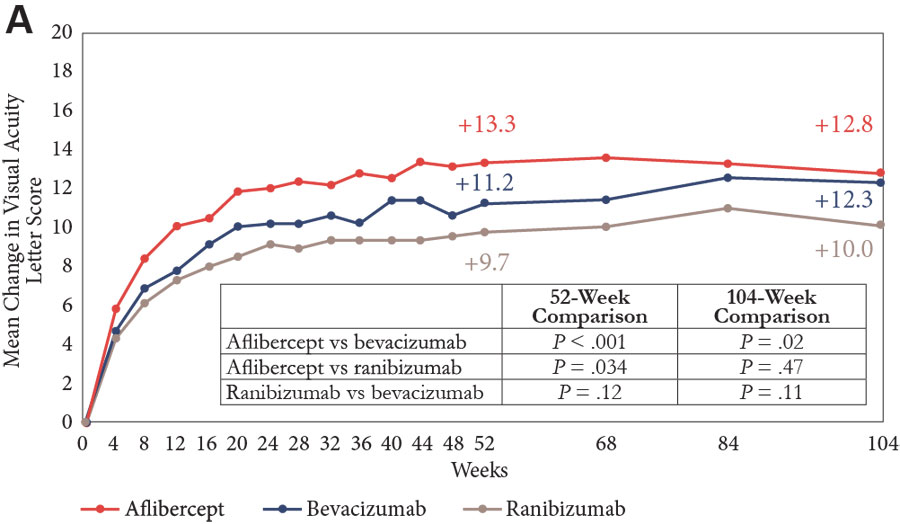

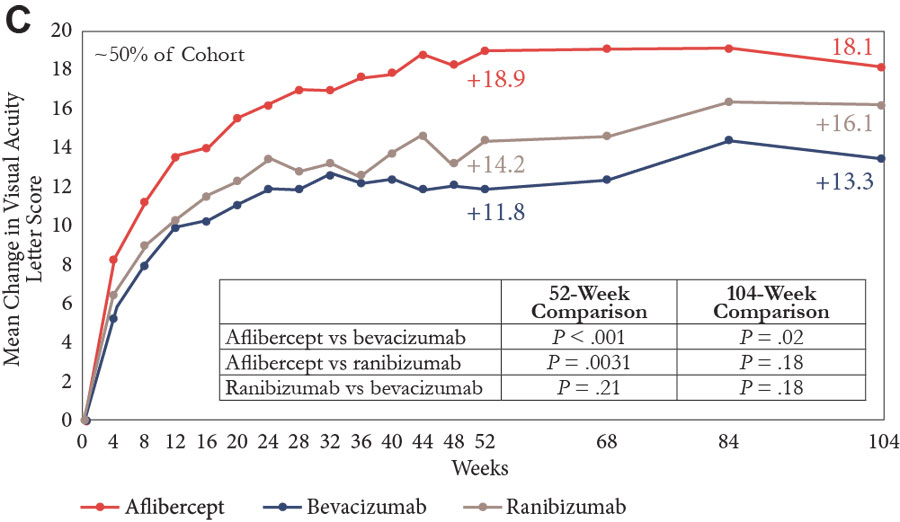

The primary end point looked at change in VA from baseline to 1 year; there was improvement in all groups, but the gain was significantly greater in the aflibercept group than in both the bevacizumab and ranibizumab groups (Figure 1A).11,13-15 A prespecified analysis of the VA outcome was also done, with patients stratified by baseline vision into subgroups with a VA of 20/40 or better or 20/50 or worse. Visual acuity improvement was similar in all 3 treatment groups among eyes with a VA of 20/40 or better at study entry, but among eyes with vision worse than 20/50, aflibercept was more effective than ranibizumab and bevacizumab for improving vision at 52 weeks, and more effective than bevacizumab at 104 weeks (Figures 1B and 1C).

| Figure 1. Mean change in visual acuity over 2 years in Protocol T.11,13-15 Graphs show data for the full cohort (A) and for subgroups with baseline visual acuity of 20/32 to 20/40 (B) and 20/50 or worse (C). |

|

Note: P values adjusted for baseline visual acuity and multiple comparisons.

Reprinted with permission from Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. This figure is not presented on behalf of the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. |

Looking at the entire population after 2 years, vision gains from baseline were numerically greater in the aflibercept and ranibizumab groups than in the bevacizumab group, but only the difference between aflibercept and bevacizumab was statistically significant (Figure 1A).11,13-15 Again, in the subgroup of eyes with better vision at baseline, all 3 agents were associated with similar VA improvement (Figure 1B). In eyes with VA of 20/50 or worse at study entry, aflibercept continued to have a statistically significant benefit compared with bevacizumab, but the difference compared with ranibizumab was no longer statistically significant after 2 years of study (Figure 1C).

Admittedly, one of the limitations for applying these results into practice is that the data cover 2 years of follow-up, whereas diabetes is a lifelong condition. But these are the data that we have, and they show that after at least 2 years, there are differences in the benefit of the various anti-VEGF agents. By applying the data from Protocol T to guide treatment decisions, retina specialists have been able to achieve better functional outcomes for their patients with DME.

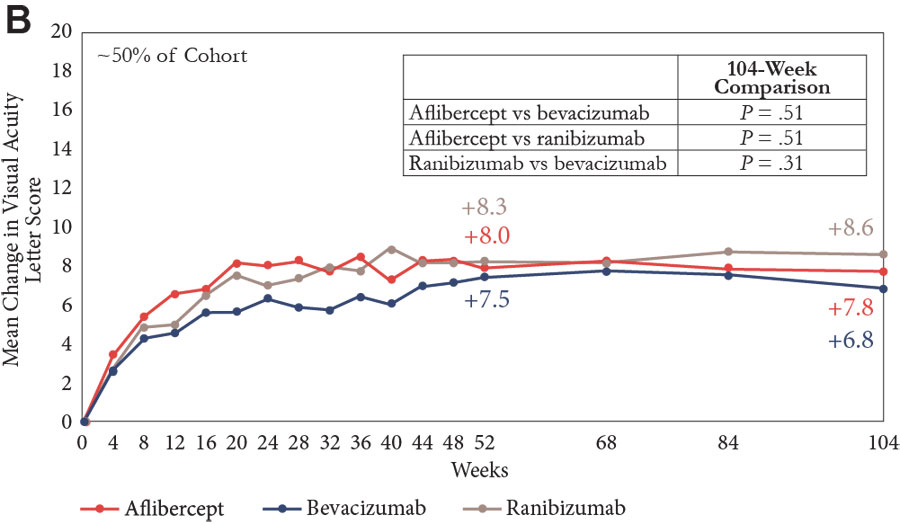

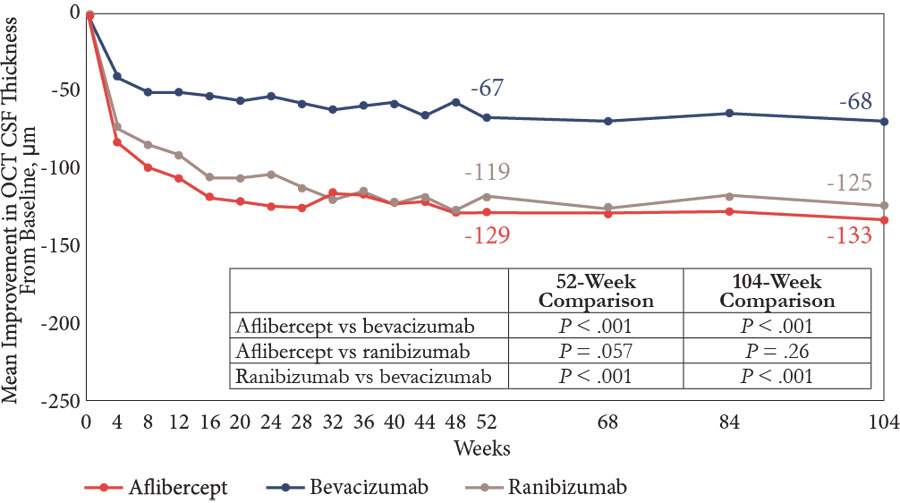

Dr Pieramici: Other data from Protocol T are worth mentioning. A post hoc analysis, in which patients were stratified according to both baseline VA and retinal thickness (a measure of macular edema), found that even in the subgroup with better VA, aflibercept and ranibizumab were associated with greater VA improvement at 1 year compared with bevacizumab among patients with a thicker retina.12 In addition, aflibercept and ranibizumab were more effective than bevacizumab both for drying the macula in the overall population at 2 years (Table) and for reducing retinal thickness in eyes with a baseline VA of 20/40 or better at 1 year (Figure 2).11 Whether or not it is necessary to completely “dry” the retina for the optimum visual outcome is controversial considering data from Protocol T suggesting that there is only a modest correlation between changes in OCT thickness and visual improvements.16

| Table. Percentage of Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity of 20/32 to 20/40 Achieving a “Dry” Macula at 2 Years in the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Protocol T Study11 |

| Percentage of Eyes |

Aflibercept

(n = 101) |

Bevacizumab

(n = 93) |

Ranibizumab

(n = 95) |

| 67%* |

37% |

64%* |

* P < .001 vs bevacizumab

Note: “Dry” defined as retinal thickness < 250 μm. |

| Figure 2. Among eyes with good vision at baseline (20/32 to 20/40), improvement of macular edema (measured as change in central subfield thickness) was greater in eyes treated with aflibercept or ranibizumab than in eyes treated with bevacizumab11 |

|

Abbreviations: CSF, central subfield thickness; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Note: P values adjusted for baseline visual acuity, OCT CSF thickness, and multiple comparisons.

Reprinted with permission from Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. This figure is not presented on behalf of the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. |

Changes in DR severity were also analyzed in Protocol T. Diabetic retinopathy can be a progressive condition, and its potential to cause vision loss increases as the severity of DR worsens. At 2 years among eyes with very severe DR at entry in Protocol T, improvement in DR severity was achieved by a significantly greater percentage of eyes treated with aflibercept than by those treated with bevacizumab.17

Dr Owens: Clear-cut data can drive change in payer policies. Therefore, payers are particularly interested in findings from head-to-head comparative trials, such as this landmark Protocol T. Because managed health care executives are responsible for a broad group of drugs, it can be challenging for them to keep up with the current literature for any one therapeutic area.

Step Therapy: Risk of Persistent Macular Edema

Dr Wong: The VA results from Protocol T represent relevant information for payers who are interested in knowing how treatments affect outcomes that make a difference to patients.11 Considering the data, would it be reasonable if a policy allowed aflibercept or ranibizumab as initial treatment for DME when a patient’s VA is 20/50 or worse, but required treatment initiation with bevacizumab for patients who have better vision?

Dr Shah: The problem with mandating treatment initiation with bevacizumab for patients with better than 20/50 vision is that we know from the 2-year data in Protocol T that bevacizumab was less effective in drying the retina compared with the other 2 agents.11 We have to remember that we are not treating patients for just 6 months or 2 years, because diabetes remains a lifelong diagnosis in most cases. Although we do not know from the Protocol T cohort if persistence of macular edema corresponded with worse VA over the long term, there is good evidence from other studies suggesting that the prolonged presence of fluid in the retina is detrimental, even in eyes with good baseline VA.18,19

We also know from the phase 3 DME studies of aflibercept and ranibizumab that vision outcomes after initiation of anti-VEGF therapy are not as good if there is a delay in the start of effective treatment.20,21 In the VISTA and VIVID trials investigating aflibercept, the control patients were initially randomized to receive laser treatment and became eligible for anti-VEGF injections after 6 months if their DME was worsening.20 Although vision improved after these patients were started on anti-VEGF therapy, their final vision was worse than that of their counterparts who were started on anti-VEGF therapy earlier. In other words, they never regained the vision lost while anti-VEGF therapy was deferred. Results from RISE and RIDE also showed that delay in starting anti-VEGF therapy was associated with poorer final vision.21 The explanation for these findings might be that persistent fluid within the retina caused permanent structural damage that limited the potential for visual recovery.

Dr Pieramici: We need to keep in mind that the time course of response to anti-VEGF therapy varies among patients. Although many patients have a huge gain in vision after a few injections, it can take a year for some to achieve maximum benefit.22 Therefore, one can reasonably argue in favor of keeping patients on the same medication for longer before switching.

There is a lack of evidence, however, to determine how well patients do if they are started on a treatment that is less effective and then switched to a more effective anti-VEGF agent. This question is being addressed in the ongoing Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Protocol AC study. This study is enrolling patients with a VA of 20/50 to 20/320 and center-involved DME, and will give insight into how step therapy requiring treatment initiation with bevacizumab affects visual outcomes. Patients are randomized to receive intravitreal aflibercept or bevacizumab with deferred aflibercept if the eye meets switch criteria that are based on OCT and VA measurements.23

Dr Shah: Tachyphylaxis could be a confounder in studies investigating the benefit of switching therapy, although it remains controversial whether or not tachyphylaxis occurs with chronic anti-VEGF therapy. Conceptually, tachyphylaxis would imply that a greater dose is needed to achieve the same effect over repeated injections of the same medication. Anecdotally, I think that tachyphylaxis is typically of minimal concern because it is rare and because it can often be overcome by switching to a different anti-VEGF agent. I recognize, however, that it can be hard for managed health care executives to make rules or decisions on the basis of these individual cases because they need to take an aggregate perspective. This is another example of a situation in which communication between the treating physicians and managed health care executives is important; the physicians can share what they see on an individual basis, and then the 2 groups can come together to find ways for improving individualized care decisions.

Dr Pieramici: In my experience, tachyphylaxis is a rare scenario, but it is a nice example of when it is helpful to be able to make an individualized decision about switching therapy. Another example of when the physician should have freedom to switch therapy is in the case of a patient who develops noninfectious uveitis with a particular anti-VEGF agent. This inflammatory reaction is not a common occurrence, but I have seen it a number of times and found that the patient could continue on anti-VEGF therapy by being switched to another drug.

Dr Wong: In a case in which the physician wants to switch anti-VEGF medications because the patient developed treatment-related uveitis, there might still be a need to go through the appeals and grievance process to obtain authorization. I think, however, there are mechanisms in place to address the request quickly. When I hear complaints that decisions are taking longer than 72 hours, I suspect the provider might have delayed in submitting the necessary supporting information or did not submit all the necessary information to drive the review process. The person who is responsible for reviewing the case will not begin looking at it until all the information is in hand.

Dr Pieramici: Dr Shah and I have shared evidence from clinical trials and case examples that demonstrate some of the problems with step therapy and prior authorization. We would be interested in learning more about the evidence from studies done by payers that show step therapy improves the quality of care.

Dr Owens: Usually, plans conduct an internal analysis looking at this issue. There are published studies showing that prior authorization and clinical management programs for diseases affecting larger patient populations have an economic benefit and preserve clinical outcomes by enhancing patient safety and compliance.24,25 There are, however, also studies that correlate step therapy and prior authorization with negative outcomes.26,27 Payers are looking for value, and not just at cost cutting. Sometimes their programs can even improve outcomes while lowering cost. More work in this area of research would be helpful.

Bevacizumab: Risks of Compounding

Dr Pieramici: Protocol T provided good evidence showing that the outcomes using bevacizumab to treat DME can be poorer than those using other anti-VEGF agents.11 Retina specialists have several other concerns related to the use of compounded bevacizumab. Contamination with the compounded agent obtained from a specialty pharmacy has always been an important issue, but the potential for comparatively higher risk using bevacizumab is even greater now that both aflibercept and ranibizumab are available in prefilled syringes.28,29 A multicenter retrospective study found that compared with intravitreal injections performed with conventionally prepared syringes containing ranibizumab, use of manufacturer-prefilled syringes reduced the rate of culture-positive endophthalmitis and improved VA outcomes.30

Dose accuracy is another quality control issue that can occur with compounded bevacizumab. In a study evaluating 21 syringes containing bevacizumab prepared at 11 compounding pharmacies, investigators found that the protein concentration of the product in 17 syringes (81%) was lower than that of bevacizumab obtained directly from the manufacturer.31 We have also been encountering periodic shortages of bevacizumab that are related to production problems in the compounding pharmacies.

Dr Shah: The presence of visually symptomatic silicone oil droplets is another safety concern with intravitreal bevacizumab that is repackaged into certain types of syringes.32-34 I wonder if managed health care executives are aware of this issue, and if there is any discussion about the possibility that a policy mandating use of bevacizumab could expose the managed health care entity to litigation risk?

Dr Wong: When anti-VEGF treatment was first being used for wet AMD, and after pegaptanib was approved, managed health care executives looked at the cost of pegaptanib and implemented step therapy forcing treatment initiation with bevacizumab. After 2 to 3 years, concerns about lack of sterility with compounded bevacizumab and the associated liability risk for a company whose policy mandated off-label use of a medication resulted in the reversal of the step-therapy requirement by some managed health care executives.

I think that history speaks to the concern that my colleagues have about safety. I first heard about the intravitreal silicone oil droplets with bevacizumab approximately 18 months ago, but I did not find much on the topic when I did a literature search at that time.

Dr Pieramici: Several papers describing symptomatic silicone oil droplets in patients receiving intravitreal bevacizumab have been published, including one that I coauthored that reported 23 cases seen over a 5-month period.32-34 Taking into consideration all the information that Dr Shah and I have discussed, I think that most retina specialists would tell you they would not want bevacizumab if they or a family member needed anti-VEGF treatment for DME.

Dr Wong: I expect that my managed health care colleagues would agree with you if they were more aware of the silicone oil droplet, dose, and sterility issues. I believe there is a need for physicians to be proactive about bringing these concerns to the attention of payers, who might not be fully informed.

I was looking at the results from the 2017 ASRS Global Trends in Retina Survey, and I found it very interesting that two-thirds of the retina specialists who responded said they would choose bevacizumab if they needed treatment for wet AMD and had to pay out of pocket.35 I am wondering if the result would be different today, considering the issues that have emerged.

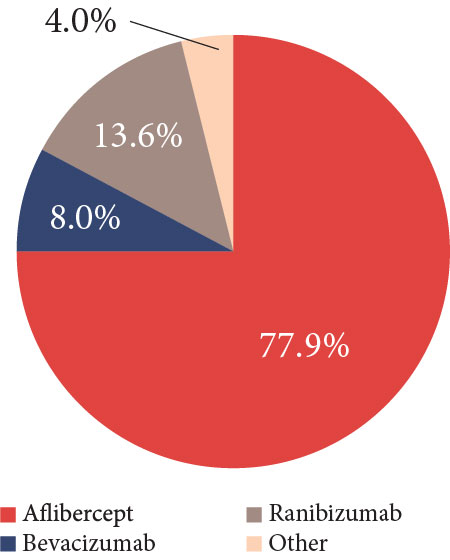

Dr Pieramici: The fact is that bevacizumab is a good drug that costs less than the on-label medications and works well for many patients. Preference for using bevacizumab depends on the clinical indication, but it has trended down. The 2019 ASRS Preferences and Trends Survey asked, If the 3 anti-VEGF agents cost the same, which would you use for treating new-onset wet AMD in the United States?36 Approximately 78% of the respondents chose aflibercept, 13.6% picked ranibizumab, and only 8% selected bevacizumab (Figure 3).36

| Figure 3. In the 2019 American Society of Retina Specialists Preferences and Trends Survey question asking which anti–vascular endothelial growth factor drug would be the primary choice for treating new-onset wet age-related macular degeneration if all the agents cost the same, 77.9% of US respondents chose aflibercept, 13.6% chose ranibizumab, 8.0% chose bevacizumab, and 0.4% chose other |

|

Consistency of care is a particular challenge that exists for patients with diabetes. Patients in the real world do not reliably return for regular follow-up and treatment.37,38 Consequently, vision outcomes of patients being treated for DME with anti-VEGF therapy in the real world are inferior to those achieved in the clinical trials. A treatment that can be administered less frequently because it has better durability provides greater patient convenience and potentially improves patient outcomes.

Additional Cost Considerations

Dr Shah: When we are talking about comparing the costs of different treatments, we also have to consider indirect costs. Ineffective anti-VEGF treatment can result in permanent vision loss, the consequences of which include decreased quality of life, increased risk of falls and fracture, and increased burdens on society and caregivers.39 I have observed an indirect benefit in that effective anti-VEGF treatment for DME has led to a decrease in the number of patients needing surgery for DR-related tractional retinal detachments. I think that Dr Pieramici would attest to that as well. Although part of the explanation might be improved diabetic care leading to better glycemic control, I think that the advent of anti-VEGF treatment for DME has had a major effect on what is a leading cause of vision loss among working-aged adults.

Dr Owens: When discussing anti-VEGF treatment selection, the cost burden for the patient should also be considered. The anti-VEGF agents used in ophthalmology are medical benefit drugs that fall under Medicare Part B coverage, and Medicare patients who do not have a supplemental coverage plan can face a significant financial liability if they are treated with one of the approved anti-VEGF medications rather than with bevacizumab. A drug that a patient cannot afford is not the best drug for that patient.

Dr Pieramici: The need to consider out-of-pocket costs for patients when comparing anti-VEGF therapies is particularly relevant for patients with diabetes (vs those with neovascular AMD) because many patients with DME are too young for Medicare and thus might not have coverage for the more expensive drugs. Cost for the patient is something that retina specialists consider for treatment selection, and it likely explains, in part, why there is so much variability in responses when retina specialists are asked about their preferred anti-VEGF treatment when presented with hypothetical clinical situations. Fortunately, manufacturer-sponsored programs and independent foundations help make it financially possible for patients to get access to these expensive medications.

Because of the financial support from an assistance program, the out-of-pocket cost can be lower for ranibizumab or aflibercept than for bevacizumab. Cost will drive a patient’s choice of treatment.

Dr Owens: I serve as a medical director for a nonprofit 501(c)(3) copayment assistance foundation. The amount of funding that is available for patients is received from donations. In Medicare, the supply usually does not equal the demand. In addition, some programs require patients to meet certain financial criteria to get assistance, and they might not qualify on that basis.

Dr Shah: Something that I have seen that is very surprising to me is that some managed health care plans have increased the out-of-pocket cost when a patient chooses to stay on bevacizumab. The patient might be doing very well on that drug, so it is difficult to understand why the plan creates a hurdle for the patient to get access to it. Perhaps an approach that minimizes copay cost for patients using bevacizumab may be helpful at preventing what would otherwise be a disincentive to use that medication.

Dr Wong: Some managed health care organizations have increased physician reimbursement for bevacizumab in order to encourage its use by the retina specialist, yet the cost to the payer is still far below the cost of using aflibercept or ranibizumab. No data show that higher reimbursement for bevacizumab affects use among the anti-VEGF agents. In oncology, some plans have increased reimbursement to favor use of generic bevacizumab over the brand-name product, which has resulted in increased use of the generic.

Facilitating Efficiency of Prior Authorization

Dr Pieramici: How would you describe the current landscape of reimbursement strategies for anti-VEGF therapy in managed health care plans?

Dr Wong: The medical policies for most plans allow use of ranibizumab and aflibercept for approved indications, but perhaps 5% to 10% of plans are more aggressive about controlling costs and, as a consequence, have instituted step therapy. Managed health care executives are motivated to drive use to what appears to be the more cost-effective treatment, but consideration is also given to whether a medication that is less expensive meets the individual patient’s needs and to the time and cost associated with going through a grievance and appeals process.

Dr Pieramici: This brings up the burden placed on clinicians by prior authorization. Some manufacturers have helped with this process, but it has become increasingly rigorous and time consuming. Although step-therapy policies might be leveling off, I wonder if the prior authorization submission will continue to be as burdensome.

Dr Owens: Physicians have to understand the perspective of the payers who are dealing with drugs that have an aggregate cost of billions of dollars. Opening the door to unmonitored use puts the executives in a difficult position because they need to account to their self-funded clients and give them some indication that they are “minding the store”, so to speak, on their behalf even if the processes are not always attractive to physicians and even sometimes to the plans.

Dr Pieramici: Dr Shah, you have been involved in prior authorization issues through work with the ASRS. What are your thoughts on how managed health care plans can facilitate the process for clinicians?

Dr Shah: Most prior authorization requests are approved. Typically, the only requirement is to provide documentation that the medication is being used for an appropriate indication. Nevertheless, the prior authorization process can be frustrating for clinicians in some situations in which there is concern that a delay in treatment initiation jeopardizes the patient’s prognosis. In my clinical experience, a delay can be especially detrimental for a patient with AMD who has experienced a sudden rapid decline in vision. In patients with a new bleed, I have seen cases in which the bleeding increased while they waited 1 or 2 weeks to start treatment; such a delay in treatment can lead to permanent vision loss. With DME, there is generally a little longer window of opportunity for starting treatment before exposing the patient to the risk of suffering permanent loss of vision.

Dr Pieramici: There are some situations with DME in which urgent treatment is needed, but my main message to managed health care executives about prior authorization is that it is particularly critical to have a faster process for anti-VEGF treatment of AMD.

Dr Wong: I know that prior authorization decisions can sometimes take a while, but part of that can be explained by how long it takes for the practice to submit all the required information. It seems that there is work that can be done on both sides to make the process more efficient so that decisions are rendered more quickly.

Dr Owens: A number of payers have turned to online prior authorizations; with this option, the approval can be almost immediate when the information provided is complete. If information is missing, however, the submission goes through a manual review process, and then the time to approval will depend on how quickly the provider supplies the information.

I attended a forum in which representatives from several managed health care organizations brainstormed ways to improve the prior authorization process. I think that, considering the cost of some of the new therapies, all the participants believe that prior authorization is here to stay. Therefore, I agree with Dr Wong that both the payer and the provider need to make an effort to find solutions for improving it.

Dr Pieramici: The interactions I have had with payers regarding prior authorization have generally been positive and resulted in a good compromise. I think that most of the representatives of the payers want patients to get the drugs and care they need. It seems to me, however, that when there is a denial, the onus always falls on the physician or someone else from the practice to contact the payer to review the situation. But I do wonder why someone from the payer side does not reach out to the provider if prior authorization is not going to be approved.

Dr Shah: I have also found that most payers are reasonable when I have had to contact them to discuss a prior authorization request. I believe they want the best outcome for patients. I also agree with Dr Pieramici that it would be nice if payers had a procedure in place whereby the provider would be contacted before a prior authorization was denied.

Dr Owens: I think that physicians should not be jaded in their thinking that managed health care organizations are motivated only to save money. I am happy to hear that Drs Pieramici and Shah have found that payers are generally willing to listen when approached about the needs of individual patients and respond to allow a policy exception. Again, policies are written for populations, not individuals. Having trained many medical directors in my career, the mantra was that they should always do what is right medically, and then everything else will fall into place.

Communication and Collaboration

Dr Wong: Regrettably, job-related time constraints do not allow the people who are responsible for payer-policy decisions to spend the time that is necessary to stay updated with the evidence and best-practice patterns, so I suggest that clinicians reach out to provide this education, either by becoming involved with the efforts of their professional societies or acting as individuals to get in touch with local payers. Likewise, my advice to my managed health care colleagues is that they should be proactive about reaching out to retina specialists so they can have a better understanding of the efficacy and safety data pertaining to anti-VEGF therapy. Speaking specifically about treating DME, managed health care decision makers need to get a better feel of what is happening in the real world and to be aware of the data that show treatment-related differences that depend on the patient’s level of vision. Then, they can start applying that information to policy development.

Dr Owens: Considering that managed health care executives have competing priorities for many different therapeutic areas, Dr Wong’s proposal for retina specialists to reach out might be the quickest way for getting the managed health care people up to speed on the new evidence and changes that are certainly occurring. With so much information that is relevant to patient care emerging so rapidly, payers cannot keep up to date. The medical information overload is real, so having these candid discussions provides a great learning experience.

Dr Shah: I thank Drs Owens and Wong for participating in this discussion with Dr Pieramici and me. I think that it is helpful and eye-opening for retina specialists to understand the challenges that payers face. Then, we can begin to think about solutions at the population level to meet payers’ needs.

Dr Pieramici: I think we have had a good discussion here, and it reflects the positive experience I have had when I meet with people from health care plans. With open communication, we can find that we all have the same goal but are looking at it from a different perspective. I can appreciate that the anti-VEGF drugs are expensive; if I was the payer, I would be concerned about overall costs and would want to know how the available agents differ. At the same time, the managed health care people need to realize that clinicians are worried about doing what is best for each patient and that there is a need to individualize decisions because there are differences among available agents, and because each patient has a different set of concerns.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

Approximately 10% of people with diabetes have a vision-threatening form of DR, defined as severe NPDR, PDR, or DME. If these conditions are not treated quickly and appropriately, vision can be irreversibly lost.

Collaboration between managed health care executives and retina specialists is important to gain an understanding of the nuances of using the various anti-VEGF agents in different clinical situations.

The available anti-VEGF agents (aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab) differ in their efficacy for treating DME and in their safety and administration schedules.

- Bevacizumab treatment for DME and DR represents off-label use and carries risks associated with compounding

- Aflibercept and ranibizumab are more effective at reducing retinal edema than is bevacizumab, but only aflibercept is also superior to bevacizumab for visual outcomes

- Evidence from Protocol T, a randomized, controlled clinical trial, shows that some patients, particularly those with poorer baseline vision, might respond more robustly to aflibercept in the first year of treatment than to ranibizumab or bevacizumab

Patient subgroups and individual patients with DR and DME have different disease characteristics and can respond to treatment much differently, supporting the value of an individualized approach to optimize outcomes. This might include switching treatment when response to one drug is suboptimal.

- Financial considerations are also an important part of patient-centered care. Even the best drug is ineffective if the patient does not receive the treatment because the drug is unaffordable.

References

- Rowley WR, Bezold C, Arikan Y, Byrne E, Krohe S. Diabetes 2030: insights from yesterday, today, and future trends. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20(1):6-12.

- International Diabetes Federation. Care & prevention. https://idf.org/our-activities/care-prevention/eye-health.html. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- Heier JS, Korobelnik JF, Brown DM, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 148-week results from the VISTA and VIVID studies. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(11):2376-2385.

- Wykoff CC, Eichenbaum DA, Roth DB, Hill L, Fung AE, Haskova Z. Ranibizumab induces regression of diabetic retinopathy in most patients at high risk of progression to proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(10):997-1009.

- Wykoff CC. Intravitreal aflibercept for moderately severe to severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR): 1-year outcomes of the phase 3 PANORAMA study. Paper presented at: Angiogenesis, Exudation, and Degeneration 2019; February 9, 2019; Miami, FL.

- Eylea [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2019.

- Lucentis [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc; 2019.

- Patel S. Medicare spending on anti-vascular endothelial growth factor medications. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(8):785-791.

- Genentech, Inc. FDA approves Genentech’s Lucentis (ranibizumab injection) for diabetic retinopathy, the leading cause of blindness among working age adults in the United States. https://www.gene.com/media/press-releases/14661/2017-04-17/fda-approves-genentechs-lucentis-ranibiz. Published April 17, 2017. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. FDA approves Eylea® (aflibercept) injection for diabetic retinopathy. https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-approves-eylear-aflibercept-injection-diabetic-retinopathy. Published May 13, 2019. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: two-year results from a comparative effectiveness randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1351-1359.

- Wells JA, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Association of baseline visual acuity and retinal thickness with 1-year efficacy of aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(2):127-134.

- Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-1203.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for DME: two-year results. Jaeb Center for Health Research Web site. http://publicfiles.jaeb.org/drcrnet/presentations/DRCR_T5_2Year_2_29_16.pptx. Accessed January 8, 2020.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Comparative effectiveness study of aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for DME. Jaeb Center for Health Research Web site. http://publicfiles.jaeb.org/drcrnet/presentations/T1_Results_Slideset_public_3_4_15.pptx. Accessed January 8, 2020.

- Bressler NM, Beaulieu WT, Glassman AR, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Persistent macular thickening following intravitreous aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for central-involved diabetic macular edema with vision impairment: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(3):257-269.

- Bressler SB, Liu D, Glassman AR, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Change in diabetic retinopathy through 2 years: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial comparing aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(6):558-568.

- Bressler SB, Qin H, Beck RW, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Factors associated with changes in visual acuity and central subfield thickness at 1 year after treatment for diabetic macular edema with ranibizumab. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(9):1153-1161.

- Bressler SB, Ayala AR, Bressler NM, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Persistent macular thickening after ranibizumab treatment for diabetic macular edema with vision impairment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(3):278-285.

- Brown DM, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Do DV, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 100-week results from the VISTA and VIVID studies. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(10):2044-2052.

- Brown DM, Nguyen QD, Marcus DM, et al; RIDE and RISE Research Group. Long-term outcomes of ranibizumab therapy for diabetic macular edema: the 36-month results from two phase III trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2013-2022.

- Gonzalez VH, Campbell J, Holekamp NM, et al. Early and long-term responses to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in diabetic macular edema: analysis of Protocol I data. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;172:72-79.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Randomized trial of intravitreous aflibercept versus intravitreous bevacizumab + deferred aflibercept for treatment of central-involved diabetic macular edema. Jaeb Center for Health Research Web site. https://public.jaeb.org/drcrnet/stdy/514. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- Keast SL, Holderread B, Cothran T, Skrepnek GH. Assessment of the effect of an enhanced prior authorization and management program in a United States Medicaid program on chronic hepatitis C treatment adherence and cost. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(5):485-491.

- Gleason PP, Phillips J, Fenrick BA, Delgado-Riley A, Starner CI. Dalfampridine prior authorization program: a cohort study. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(1):18-25.

- Carlton RI, Bramley TJ, Nightengale B, Conner TM, Zacker C. Review of outcomes associated with formulary restrictions: focus on step therapy. Pharm Times. April 6, 2010;2(1). https://www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/ajpb/2010/vol2_no1/Review-of-Outcomes-Associated-With-Formulary-Restrictions-Focus-on-Step-Therapy. Published April 6, 2010. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- Park Y, Raza S, George A, Agrawal R, Ko J. The effect of formulary restrictions on patient and payer outcomes: a systematic literature review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(8):893-901.

- Genentech, Inc. FDA approves Genentech’s Lucentis (ranibizumab injection) 0.3 mg prefilled syringe for diabetic macular edema and diabetic retinopathy. https://www.gene.com/media/press-releases/14708/2018-03-21/fda-approves-genentechs-lucentis-ranibiz. Published March 21, 2018. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. FDA approves Eylea® (aflibercept) injection prefilled syringe. https://newsroom.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-approves-eylear-aflibercept-injection-prefilled-syringe. Published August 13, 2019. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- Storey PP, Taugeer Z, Yonekawa Y, et al; Post-Injection Endophthalmitis (PIE) Study Group. The impact of prefilled syringes on endophthalmitis following intravitreal injection of ranibizumab. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;199:200-208.

- Yannuzzi NA, Klufas MA, Quach L, et al. Evaluation of compounded bevacizumab prepared for intravitreal injection. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(1):32-39.

- Yu JH, Gallemore E, Kim JK, Patel R, Calderon J, Gallemore RP. Silicone oil droplets following intravitreal bevacizumab injections. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2017;10:142-144.

- Khurana RN, Chang LK, Porco TC. Incidence of presumed silicone oil droplets in the vitreous cavity after intravitreal bevacizumab injection with insulin syringes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(7):800-803.

- Avery RL, Castellarin AA, Dhoot DS, et al. Large silicone droplets after intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin). Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2019;13(2):130-134.

- Shah GK, Stone TW, eds. 2017 ASRS Global Trends in Retina Survey. Chicago, IL: American Society of Retina Specialists; 2017.

- Stone TW, Hahn P. ASRS 2019 membership survey: preferences and trends. Poster presented at: 37th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Retina Specialists; July 26-30, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Ciulla TA, Bracha P, Pollack J, Williams DF. Real-world outcomes of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in diabetic macular edema in the United States. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(12):1179-1187.

- Holekamp NM, Campbell J, Almony A, et al. Vision outcomes following anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment of diabetic macular edema in clinical practice. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;191:83-91.

- Köberlein J, Beifus K, Schaffert C, Finger RP. The economic burden of visual impairment and blindness: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):e003471.

Back Top