Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Point-of-Care301

Readying for an Expanded Scope of Practice in California: Preventing HIV Infection in the Pharmacy Setting

PDF Content »

Introduction: A Call for Pharmacists’ Expanded Role in HIV Prevention Services

Addressing the national call to action to reduce the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, especially in high-risk, yet underserved populations, California has proactively led the way as the first state to allow pharmacists to furnish HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for appropriately identified candidates.1,2 While reviewing the provisions and regulations of the pioneering legislation that made this expanded scope of pharmacy practice possible, this continuing education and training monograph will address current guidelines for the provision of PrEP and PEP, key pharmacologic considerations, and practice management strategies.

Epidemiologic Imperatives Mean Practice Opportunities for Pharmacists

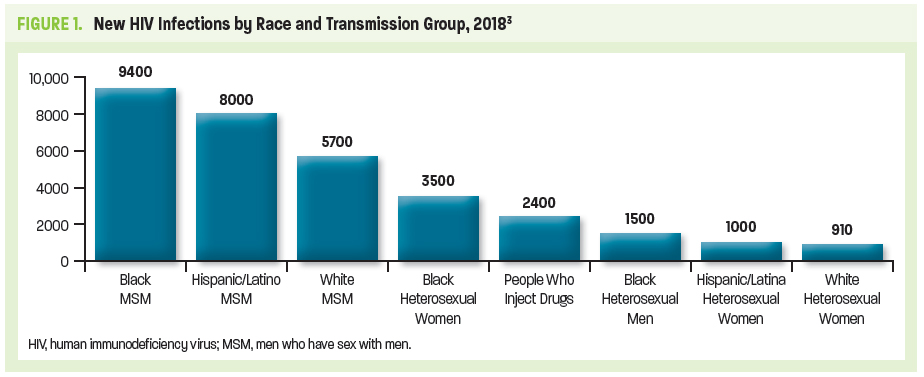

Approximately 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV today, with 1 in 7 HIV-infected individuals unaware of their infection. Latest estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that there were 36,400 new HIV infections in the United States in 2018. Populations including men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender persons, and black and Hispanic/Latinx persons continue to be disproportionally affected. While new annual infections in the United States have been reduced by more than two-thirds since the mid-1980s when HIV initially emerged, black and Hispanic/Latinx populations are among those that continue to have high rates of undiagnosed infections (Figure 1).3,4

The burden of HIV has often been measured by the number of individuals dying from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related complications. Although on an international level, HIV/AIDS remains among the leading fatal infectious diseases, AIDS-related deaths in the United States have dramatically dropped because of advances in HIV treatment and management.5,6 Nonetheless, the United States government continues to spend more than $20 billion annually in direct health expenditures related to HIV care and prevention. This underscores HIV as a persistent public health threat despite greater disease awareness, highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), and proven prevention strategies and tactics.7

The advent and continual evolution of ART has allowed people living with HIV (PLWH) to enjoy longer, healthier lives through reduction in HIV-related morbidity and mortality at all stages of HIV infection.8 ART has also given rise to modalities designed to limit HIV acquisition in HIV-negative individuals—notably, specific antiretroviral drug combinations used as PrEP and PEP. PrEP is prescribed for HIV-negative people who are at high risk of HIV exposure, whereas PEP is prescribed for HIV-negative people who have had a single high-risk exposure.9

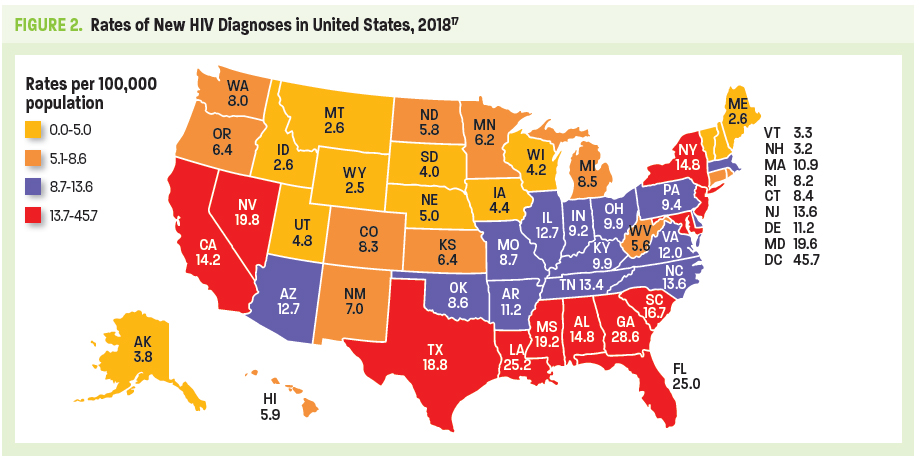

Despite PrEP demonstrating efficacy in reducing HIV transmission rates by as much as 74% to 99% when taken daily (depending on mode of transmission—sexual or injection drug use [IDU]), fewer than 1 in 4 potential candidates receive PrEP.10-12 High risk populations with the lowest rates of PrEP uptake include young MSM, racial or ethnic minority groups, and individuals living in the South or Southeast regions of the United States. Without preventive efforts, 1 in 2 black MSM and 1 in 5 Hispanic/Latino MSM will contract HIV in their lifetime.13,14 The majority of PrEP uptake (75%) has been among white gay and bisexual men, predominantly those living in the Northeast or on the West Coast.15 As of 2017, the PrEP-to-need ratio (ie, the number of PrEP users divided by new HIV diagnoses) was lowest among individuals age ≤24 years or ≥55 years. Geographically, lowest ratios were seen throughout the South, despite 52% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States being attributable to this region (Figure 2).16

Perceived stigma, distrust of the medical system, lack of PrEP awareness among patients and clinicians, and limited access due to cost are theorized as potential reasons why PrEP uptake is currently low. Distrust of the medical system may be tied to stigma, as patients are often reluctant to speak with their health care providers about their sexual activity or risky behaviors. This is especially true among MSM.18 Clinicians may be unfamiliar with how to monitor patients on PrEP, and may not realize that a less costly generic PrEP formulation may soon be available.13,15 In many locales, required preauthorization has been one of the most common barriers to prescribing PrEP, according to primary care and HIV-treatment providers.13 Without adequate insurance coverage, the annual cost of continuous PrEP use (including guideline-based interval visits, laboratory testing, and prescription refills) is more than $10,000. Although there are federal and state-level programs to increase access to PrEP, (see page 19, Your Patient's Advocate: Coordination of Care, Financial-Assistance Resources, and Pharmacist Resources) cost may be a barrier for young black and Latino MSM and transgender women—many of whom are likely to be uninsured or underinsured—and who may benefit the most from PrEP.15

Building on an Established Practice Foundation

Through expansion of scopes of practice, pharmacists are demonstrating their ability to work in chronic disease management and to dispense or administer certain drugs and biologic products.14,19 Many states, in an effort to curb the soaring rates of drug overdose, now allow pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription.15,20 Frequently, pharmacists in patient-centered medical homes lead medication-management services and help patients meet clinical-management goals as diverse as control of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), systolic blood pressure, and serum lipids; and increasing vaccination rates and medication adherence.21 In certain states, upon meeting additional credentialing or board recognition, pharmacists are authorized to dispense contraceptives, nicotine-replacement therapy, and travel medications.13,19 Further, community pharmacists are extremely well-positioned to address certain public health problems, since high-risk patients visit their community pharmacies more often than their primary care providers (PCPs).21

Within the realm of HIV disease management, pharmacists have already demonstrated high levels of success in increasing ART adherence through comprehensive means: identification of patient-specific barriers (eg, health literacy, cognitive factors, mental-health and substance-use comorbidities, economic factors); detection of therapy-related barriers (eg, adverse effects, drug-drug interactions); and recognition of service-delivery barriers (eg, patient-provider relationships, providers’ cultural competencies).22

An obvious next step in expanding the pharmacist’s role in HIV care is the prescribing and management of PrEP and PEP. Experienced in the principles and practices of chronic-disease medication management, and knowledgeable of HIV pharmacology, the pharmacist can play an essential role in HIV prevention across diverse practice venues.23,24

The Evolving Scope of Pharmacy Practice: The Future of HIV Prevention Is Here

California is among the 3 top-ranked states for new HIV diagnoses among adults and adolescents, with an estimated 4800 new cases in 2018 (Texas, 4400; Florida, 4400).25 Responding to this public-health imperative to reduce HIV incidence in California, Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) and assembly member Todd Gloria (D-San Diego) drafted and introduced legislation to expand PrEP and PEP access through inclusion of pharmacists as providers of HIV-prevention care.2

California Senate Bill (SB) 159, approved October 2019, amends Section 4052 of the California Business and Professions Code and adds Sections 4052.02 (regarding PrEP) and 4052.03 (regarding PEP) to allow pharmacists to furnish PrEP and PEP upon completion of a training program approved by the California Board of Pharmacy. Further, SB 159 prevents any health care service plan or delegated pharmacy benefit manager from prohibiting a pharmacy provider from dispensing PrEP or PEP. Additionally, SB 159 amends the Health and Safety Code and the Insurance Code to prohibit health care service plans or health insurers from subjecting antiretroviral drugs for HIV treatment, or as used as PrEP or PEP, to prior authorization or step therapy (failing inexpensive options first).2

Of particular importance, SB 159 recognizes the pharmacist’s furnishing of PrEP and PEP as a benefit under Medi-Cal (California Medicaid; subject to approval by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) and requires Medi-Cal to establish a fee schedule for these pharmacist services. The rate of reimbursement for pharmacist services is outlined at 85% of the fee schedule for physician services under Medi-Cal. Pharmacists will also be enrolled as ordering, referring, and prescribing providers under the Medi-Cal program.

Topic-specific provisions and requirements under California SB 159 will be addressed throughout this monograph.

HIV Essentials for the Pharmacist

The HIV Viral Life Cycle and Antiretroviral Targets

HIV targets and replicates within CD4 T-lymphocytes (T helper cells)—cells that are critical to adaptive immune responses—leading to CD4 destruction and, thereby, decreasing the functionality of the immune system and increasing the risk of opportunistic infections.26,27

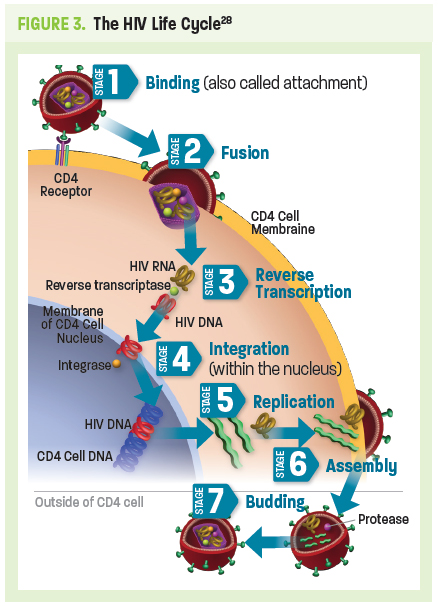

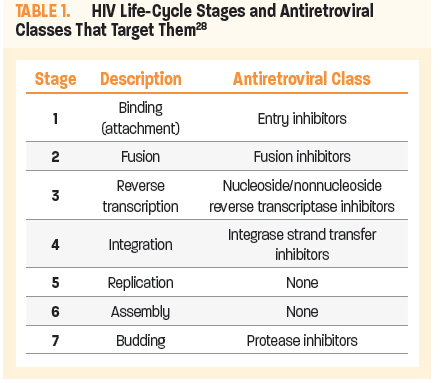

The HIV life cycle (Figure 3) consists of 7 stages, 5 of which are targets for current ARTs (Table 1).28 The first stage is binding (or attachment): HIV binds to receptors on the surface of a CD4 cell. The second stage is called fusion; upon attachment, the viral envelope fuses with the CD4 cell membrane, allowing HIV to enter the host cell and release viral components. Stage 3 is reverse transcription: inside the CD4 cell, HIV releases and uses a reverse transcriptase enzyme to convert HIV RNA (ribonucleic acid) into HIV DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). HIV DNA then enters the nucleus and proceeds to integration (stage 4), during which HIV releases integrase, an enzyme that integrates viral DNA into the DNA of the host CD4 cell. In stage 5, replication, the machinery of the host CD4 cell produces long chains of HIV proteins (building blocks for more HIV); while in stage 6, assembly, new HIV proteins and HIV RNA move to the surface of the cell and combine as immature (noninfectious) HIV. The seventh and final step in the HIV life cycle is budding, wherein newly formed immature HIV pushes itself out of the host CD4 cell. Protease, an HIV enzyme released from the new HIV breaks up long protein chains in the immature virus, creating a new and mature (infectious) virus.28

Understanding the Immunologic Basis for

HIV Testing

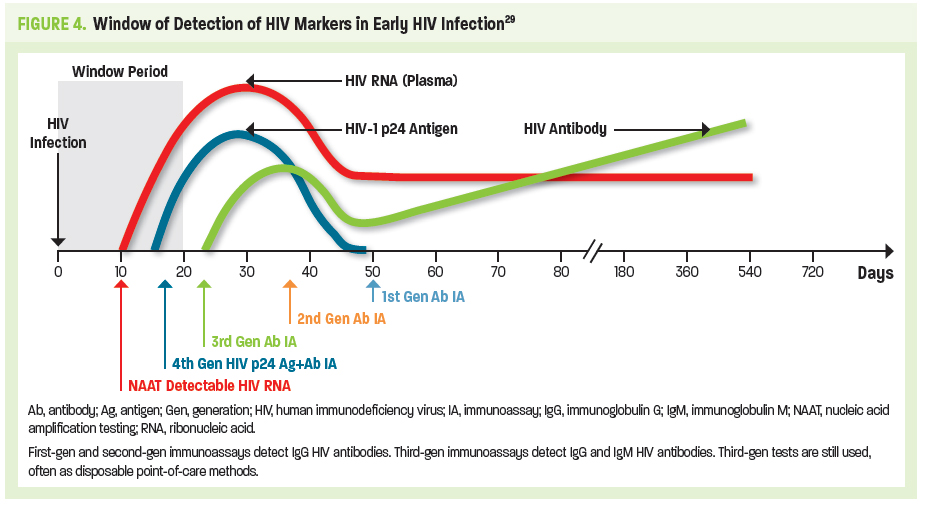

Following release of mature HIV from the CD4 cell, the viral RNA is initially present in the plasma without recognition of the host immune system. By approximately day 17, the HIV p24 antigen is present. The body recognizes this viral protein as foreign, thereby eliciting an immune response with production of specific anti-HIV antibodies. During this initial 17-day period neither HIV antigen (Ag) nor anti-HIV antibodies (Ab) are detectable with HIV tests used most commonly in the community setting. Yet HIV RNA may be detectable as early as day 10 with more highly specialized nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). That is, during this window period, an HIV-infected person may have an HIV-negative test result (Figure 4).29,30

Use of 4th-generation (gen) antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) tests is the current standard of care. Usually performed in the laboratory setting, this immunoassay (IA) detects both p24 antigen and HIV-specific antibodies at approximately day 18. Third-gen IAs detect immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) HIV antibodies at about day 23. Third-gen tests are still used, often as a point-of-care testing modality. A negative HIV test following a high-risk exposure should always be clinically correlated with any signs or symptoms of acute HIV infection, and repeat testing after the window period should be advised.29,30

PrEP 101

Introduction

PrEP is the use of specific combinations of antiretroviral agents to reduce the risk of HIV infection. It is intended for HIV-negative individuals who are at risk of infection through sexual intercourse or injection drug use, including sexually active MSM, heterosexual men and women, and transgender persons; and as an alternate prevention strategy for individuals receiving PEP who continue to engage in high-risk behavior or who have received multiple courses of PEP. Sexually active adults and adolescents are defined as people engaging in anal or vaginal sex in the past 6 months.31

At the time of this publication, CDC guidelines recognize only 2 drug regimens for use as PrEP.31,32

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300 mg/emtricitabine (FTC) 200 mg (fixed-dose combination) once daily (Truvada®, US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]-approved for treatment of chronic HIV infection in 2004 and FDA-approved for PrEP in 2012)

Approved for all persons at risk of HIV transmission

Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) 25 mg/FTC 200 mg (fixed-dose combination) once daily (Descovy® approved October 2019)

Indicated for all persons at risk of HIV acquisition, with the current exception (ie, has not been studied) of those at risk through receptive vaginal sex or injection drug use.33

Key clinical trials involving TDF/FTC used as PrEP—including iPrEx (Iniciativa Profilaxis Pre-Exposición [Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative]), Partners PrEP (Partners Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Study), FEM-PrEP (Preexposure Prophylaxis Trial for HIV Prevention among African Women), and TDF2 (Botswana TDF/FTC Oral HIV Prophylaxis trial)—demonstrated safety and efficacy of the combined use of these 2 nucleotide/nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs/NtRTIs) as HIV PrEP across all at-risk populations, including MSM, heterosexual HIV-discordant couples, heterosexual men and women, and people who inject drugs (PWID).31,34-38 As noted, TDF and FTC target reverse transcription, stage 3 in the HIV life cycle (Figure 3). Once phosphorylated intracellularly, creating diphosphate and triphosphate metabolites, respectively, these nucleotide/nucleoside analogs inhibit HIV reverse transcriptase by competing with viral substrates and, thereby, causing DNA chain termination and preventing viral RNA conversion.39

Whereas older NRTIs were characterized by serious toxicities (including bone marrow suppression, peripheral neuropathy, lactic acidosis, and pancreatitis) secondary to their effects on human cellular mitochondrial DNA, these newer NRTIs are weaker inhibitors of mitochondrial DNA and are less likely to result in significant toxicities.

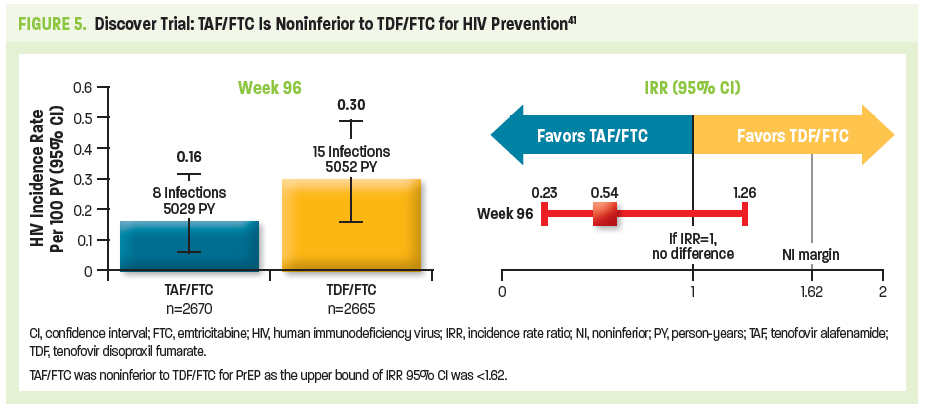

TDF/FTC remained the sole FDA-approved antiretroviral regimen for use as PrEP until October 2019. The randomized, double-blind, active-control DISCOVER trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of TAF/FTC vs TDF/FTC in high-risk cisgender MSM and transgender women (in North America and Europe).40 Eligible patients (N=5387; mean age 36 years) had engaged in ≥2 episodes of condomless anal sex in the preceding 12 weeks or received the diagnosis of rectal gonorrhea/chlamydia or syphilis in the preceding 24 weeks. The primary endpoint was the rate of HIV infection per 100 person-years (PY) when 50% of patients had completed 96 weeks of PrEP use. Longer term results, reported once all participants completed 96 weeks, showed that just 23 HIV diagnoses occurred during the study period—an infection rate of 0.16/100 PY for TAF/FTC vs 0.30/100 PY for TDF/FTC (Figure 5). TAF/FTC was associated with significantly better bone and renal safety profiles compared with TDF/FTC, although both combinations were well-tolerated and associated with low rates of discontinuation due to adverse events. Combination TAF/FTC was considered noninferior to TDF/FTC in preventing HIV infection, thereby leading to expanded PrEP medication options for persons at risk of HIV acquisition, except for those at risk through receptive vaginal sex or injection drug use.

PrEP: Further Pharmacologic Considerations

Both TDF and FTC are primarily excreted through the kidneys; therefore, patients with impaired renal function—based on estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl), and as calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault equation—are at risk.42 Use of TDF/FTC as PrEP is not recommended for persons with eCrCl <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Further, reduced-dosing strategies for TDF/FTC as PrEP have not been developed.31

In contrast, TAF is metabolized by the lysosomal multifunctional enzyme cathepsin A and can be used in patients with more compromised renal function (eCrCl ≥15 mL/min/1.73 m2) or patients on hemodialysis (although the FTC component of TAF/FTC is not recommended for patients with eCrCl <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and therefore TAF/FTC for PrEP is not recommended for patients with eCrCl <30 mL/min/1.73 m2).33 The serum half-life of TAF is 0.5 hours, with an intracellular half-life of 150–180 hours. In contrast, the serum half-life of TDF is 17 hours, with an intracellular half-life of >60 hours. The bone- and renal-related adverse effects associated with TDF are less likely to occur with TAF due to this lower plasma exposure. Of note, in the context of HIV treatment (ie, not PrEP), switching patients who show a decline in bone mineral density from TDF-containing to alternative ART regimens was shown to increase bone mineral density, but the clinical significance of this increase remains unknown.43

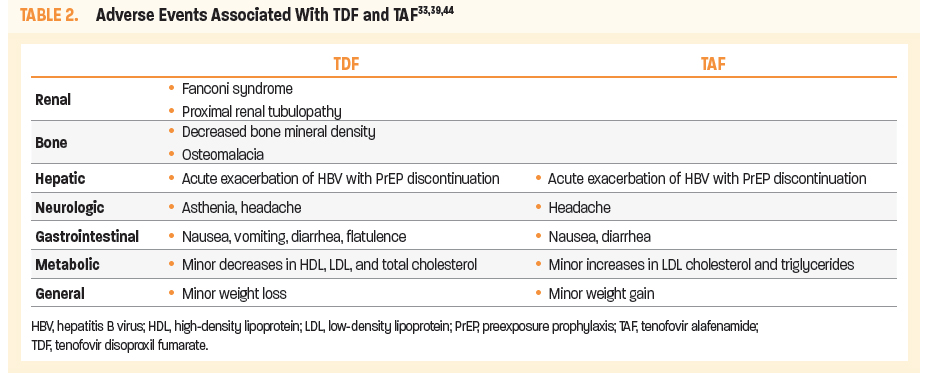

While TAF/FTC appears to have safer kidney and bone toxicity profiles than TDF/FTC, TDF/FTC is associated with lower lipid levels and weight loss.31,33,39,44 However, the CDC PrEP guidelines do not provide further parameters for consideration when choosing between these 2 PrEP regimens.32 Other, less significant or transient adverse effects of TDF/FTC include asthenia, headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, flatulence, minor decreases in high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and total cholesterol, and minor weight loss.39 TAF/FTC may be associated with headache, nausea, diarrhea, minor increases in LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, and minor weight gain33 (Table 2).

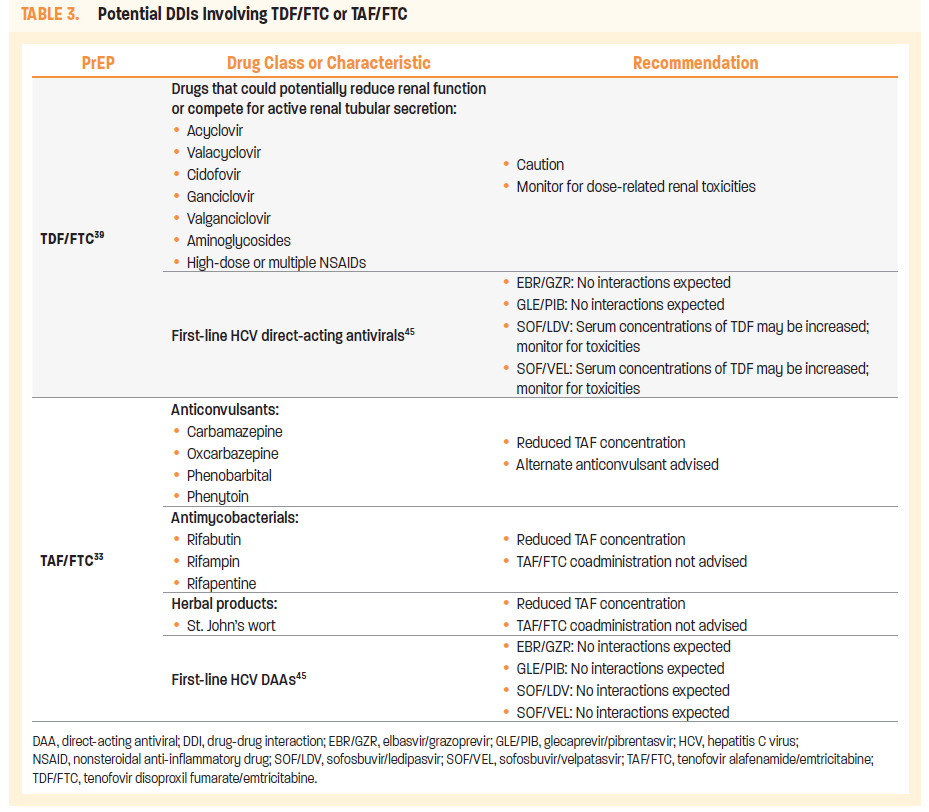

Table 3 lists potential drug-drug interactions (DDIs) with TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC. As the incidence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) is increased in populations at risk of HIV acquisition, first-line HCV direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens are listed, including those with no potential DDIs.

The start-up syndrome of headache, nausea, and flatulence occurring in the first month of TDF/FTC use as PrEP occurs in a minority of patients and typically resolves within 3 months, sooner for many patients. Patients should be forewarned of this possibility, instructed on the use of over-the-counter medications for symptom management, and educated regarding more serious signs and symptoms—including those of acute HIV infection—that should be reported on an urgent basis.31,46

One issue that clinicians should be aware of, regarding both TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC, is that patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) may develop severe acute exacerbation of HBV if they discontinue either of these PrEP regimens.33,39

Pretreatment Determination of PrEP Eligibility2,31

Determination of an individual’s eligibility for PrEP includes several required clinical components:

Conduct a comprehensive behavioral risk assessment (sexual; injection drug use) to identify appropriate PrEP candidates

Confirm HIV-negative status: select preferred HIV tests and/or accurately interpret HIV test results

Perform laboratory assessment for PrEP-associated risks and correlate clinically (include other baseline labs required for

PrEP initiation)

Hepatitis A virus (HAV), HBV, HCV screening serology

Serum creatinine

Sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing

Pregnancy testing (for women of childbearing potential)

Comprehensive Behavioral Risk Assessment

(Sexual and Injection Use)31

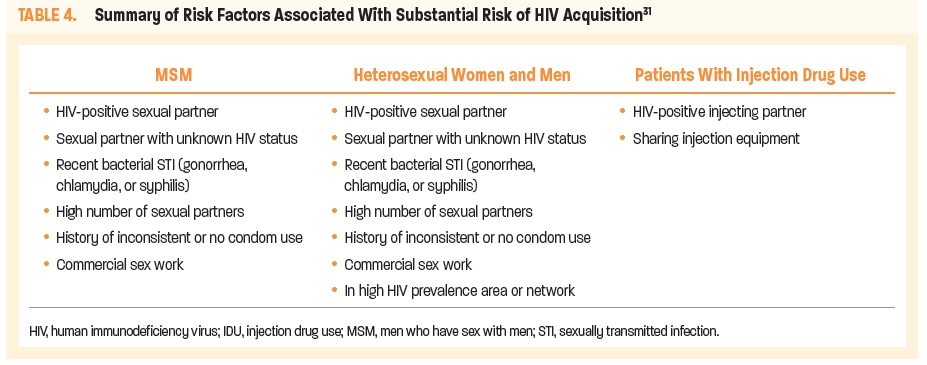

A comprehensive behavioral risk assessment (including sexual and drug-injection use) is critical for identification of appropriate PrEP candidates (Table 4). It may also inform additional needs for in-depth education, risk-reduction counseling, and community-based patient-support services. For an in-depth discussion, go to: Embracing Sexual Wellness and Discussing HIV Risk on page 17 in this monograph.

Confirmation of HIV-Negative Status

Section 4052.02 of the California Business and Profession Code requires pharmacists to provide HIV testing to confirm HIV-negative status within 7 days prior to PrEP provision.2 The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) Office of AIDS contributes funding for health departments’ opt-out HIV testing (universal testing; an individual may decline) in medical care settings, as well as for targeted HIV testing to reach high-risk populations.47 However, pharmacists may conduct on-site HIV testing.

Currently, 4th-gen combined antigen/antibody tests are both recommended and preferred. Antigen/antibody tests utilizing blood from a vein can usually detect HIV infection 18 to 45 days after an exposure, while rapid antigen/antibody tests with finger prick blood may detect HIV 18 to 90 days after exposure.48 Other HIV tests are recognized and allowed. Antibody-only tests take 23 to 90 days to detect HIV infection based on blood or oral fluid. As of June 2018, CLIA-waiveda rapid HIV tests, suitable for use in nonclinical settings, and involving fingerstick whole blood or venous whole blood, include the following (only the Determine™ test below is a 4th-gen combined antigen/antibody test; all others only test for antibodies to HIV-1 and HIV-2)49:

Chembio DPP® HIV-1/2 Assay

Chembio SURE CHECK® HIV 1/2 Assay

Clearview® HIV 1/2 STAT-PAK®

Alere Determine™ HIV-1/2 Antigen/Antibody Combo Test

INSTI® HIV-1/HIV-2 Antibody Test

OraQuick ADVANCE® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test

Uni-Gold™ Recombigen® HIV-1/2 Antibody Test

aCLIA-waived means without the need for the conduct of more stringent standards under the Clinical Laboratory Improved Amendments.47

Rapid tests involving whole-blood finger prick or venipuncture/plasma samples can yield results in approximately 10 minutes. No further testing is needed if test results are negative, but positive tests must be confirmed with more specific conventional blood tests, with results available in <1 hour to several days. Oral HIV tests are not recommended in these clinical scenarios.31

The CDC provides a website listing FDA-approved diagnostic HIV tests including a list of CLIA-waived tests: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/laboratorytests.html.

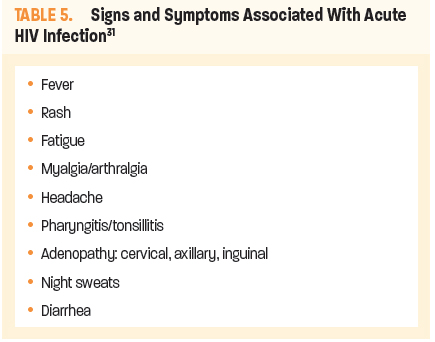

When interpreting HIV-test results, clinicians must keep in mind the approximately 18-day period (see Figure 4), during which time even the 4th-gen combined antigen/antibody tests may fail to detect early infection. Therefore, all patients should be questioned regarding specific signs and symptoms suggestive of or consistent with early/acute HIV (Table 5). Only with both negative HIV testing and negative screening for these signs and symptoms should there be further consideration of PrEP prescribing.

Laboratory Assessment for PrEP-Associated Risks

Estimated creatinine clearance (as calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault equation) and hepatitis serology are critical in determining

PrEP eligibility.

TDF/FTC is not recommended for persons with eCrCl

<60 mL/min/1.73 m2; reduced-dosing strategies for TDF/TDF as

PrEP have not been developed.31

TAF/FTC is not recommended for persons with eCrCl

<30 mL/min/1.73 m2.33

HBV infection is not a contraindication, but HBV status must be known and documented prior to PrEP initiation. Discontinuation of PrEP may be associated with acute exacerbation of HBV. Patients positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) should be referred to an appropriate clinician for evaluation and consideration for HBV treatment.31

TDF/FTC is a safe and effective HIV-prevention strategy for women who are at substantial risk of HIV acquisition, including during conception, pregnancy, and the postpartum period. TAF/FTC is not approved in those having receptive vaginal sex. Continuing TDF/FTC during breastfeeding may be beneficial for some women, however, long-term safety of infant exposure to TDF/FTC has not been determined. TDF/FTC does not reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptives.31

Pretreatment Requirements Once PrEP Eligibility Is Determined

Having established the patient’s PrEP eligibility, the PrEP provider’s additional pretreatment requirements address the following clinical activities31:

Prescribe safe and effective PrEP regimens for eligible HIV-uninfected persons

Educate patients about the selected PrEP regimen to maximize

safe use

Provide counseling and effective contraception to women on PrEP who do not wish to become pregnant

Provide other patient-centered counseling regarding the following:

Medication-adherence to achieve and maintain protective

tissue levels

HIV risk reduction; including discussion/provision of prevention-services referrals

Review PrEP discontinuation and resumption requirements

PrEP Selection and Prescribing

Once the patient’s eligibility is established, few considerations will impact the selection of PrEP regimen. The most critical is the patient’s renal function: TDF/FTC should not be prescribed for individuals whose eCrCl is less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, because of TDF’s renal clearance.31,33 Mode of sexual exposure may also influence selection; as mentioned previously, TAF has not been approved for those at risk through receptive vaginal sex.32 Patients should report all medications that they are currently taking. In addition, issues of bone density (especially if the patient is over 50 years of age), cholesterol, and weight change may also be considered.31,33 In clinical practice, selection of PrEP regimen may come down to the practical concerns of insurance coverage and cost.15 Whereas single-agent TDF is currently available as a generic 300 mg tablet, an FTC combination with TAF is only available in brand form. Generic formulations of FTC and TDF and singular FTC are expected September 2020.50

Although Section 4052.02 of the California Business and Professions Code defines PrEP as a fixed-dose combination of TDF 300 mg with FTC 200 mg, it allows for another drug or drug combination determined by the board to meet the same clinical eligibility recommendations provided in CDC guidelines.2 CDC guidelines provide for use of TDF monotherapy for PWID and for heterosexual men and women, based on prior trials demonstrating efficacy in these specific populations. There are no data supporting TDF monotherapy for MSM which, therefore, is not recommended.31

CDC PrEP guidelines do not currently recommend intermittent, episodic, or other discontinuous-dosing protocols. However, evidence-based on-demand or event-driven protocols are endorsed by other organizations. For example, 2-1-1 is a PrEP dosing protocol recommended for MSM engaging in anal sex without condoms (not recommended for vaginal sex) by the International Antiviral Society–USA (IAS–USA) and the World Health Organization (WHO).51,52 Named on the basis of the number and timing of PrEP tablets taken, 2-1-1 provides the following recommendations53:

A loading dose of 2 TDF/FTC tablets is taken 2–24 hours before

anal sex

A third tablet is taken 24 hours after the first dose

A fourth tablet is taken 24 hours later

If there is another sexual exposure within 7 days of the last dose,

1 tablet is taken 2–24 hours before anal sex, 1 tablet 24 hours after the first dose, then 1 tablet 24 hours after the second dose

While efficacy of this dosing protocol has been demonstrated in the IPERGAY study, its employment should be discussed with the patient’s primary care physician or another PrEP provider. Of particular note, this study did not include TAF/FTC and these recommendations do not apply to its use with the 2-1-1 protocol.51,53

Basic Medication Education

Basic medication-education components include the following:

Which PrEP medication is being prescribed? How is it taken?

What is the dosing schedule?

Time to maximum HIV-prevention effectiveness, as based on exposure mode (Table 6)

How to manage missed doses

Common signs and symptoms suggestive of acute HIV infection (Table 5)

Common side effects of TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC

What quantity will be dispensed?

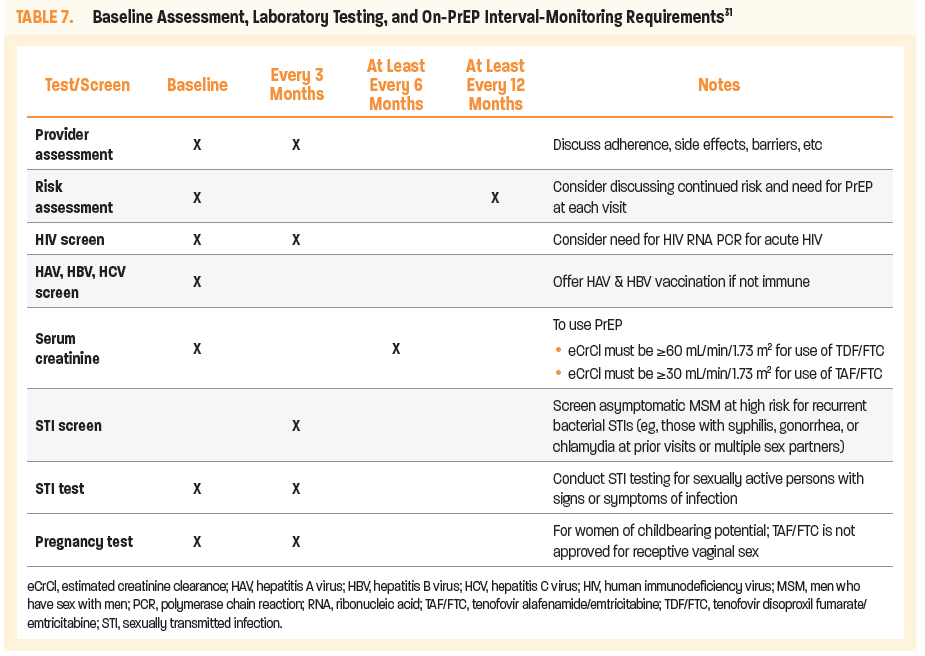

Requirement to remain under the care of the prescriber for required interval monitoring (Table 7)

Time to maximum HIV prevention varies with mode of sexual exposure (Table 6). Patients should be advised that condom use is critical while tissue concentrations remain low, and that ongoing, consistent use of condoms is necessary for the prevention of both HIV and other STIs.31

Effective HIV prevention requires a high level of daily adherence to the PrEP medication, but there is some leeway for missed doses. The STRAND trial showed that 6 to 7 doses per week are required to maintain protective vaginal tissue concentration; fewer doses per week may be adequate to maintain colorectal tissue concentrations. Nonetheless daily adherence should be stressed for all persons on PrEP. Should a patient report missing a dose, instruct the patient to take a single missed dose as soon as it is remembered. If, however, it is nearly time for the next dose, the patient should proceed with the regular dosing schedule.31

Section 4025.02 allows pharmacists to furnish at least a 30-day, and up to a maximum 60-day supply of the PrEP medication, while the CDC PrEP guidelines allow for a maximum 90-day supply. Consideration of lesser quantities for high-risk individuals, whom you may want to evaluate sooner or more frequently, may be advisable. Alternatively, the pharmacist can provide a full 60-day prescription and follow up with the patient sooner than that, or more frequently by electronic means. It is important that the patient is advised that the pharmacist's prescribing of PrEP is limited to 60 days' duration per 2-year period, and that follow-up with or referral to a PCP is planned.2,31

Patient-Centered PrEP Counseling: Adherence and Behavioral Risk Reduction

Effective use of PrEP in preventing HIV is grounded on adherence to daily dosing.31 Key tactics for successful medication-adherence counseling may include the following:

Simplified education and explanations; eg, dosage schedule, impact of adherence on PrEP efficacy

Strategies that address patient-specific adherence barriers; eg, substance use

Nonjudgmental adherence monitoring; eg, normalizing occasional missed doses, reinforcing success, encouraging condom use

As adverse effects may impact PrEP adherence, pharmacists should counsel patients regarding the following concerns31:

Common side effects (headache, nausea, and flatulence)

that typically resolve within the first month of taking PrEP

(start-up syndrome) and over-the-counter medications for

symptom management

Signs or symptoms of acute HIV infection (Table 5) or acute renal injury, both of which require urgent intervention

PrEP adherence is supported by effective HIV risk-reduction education. Counseling should include information about substance use and protection from STIs with consistent condom use.31,54,55 Whether recreational and/or associated with injection practices, psychotropic substances may decrease inhibitions, increase risk tolerance, and reduce self-efficacy with regard to risk-reduction practices.56 Patients also should be reminded that PrEP does not protect against other STIs. Such personal risk-reduction practices—with emphasis on consistent condom use—remain critical, even when one is using PrEP. Adherence should also include:

Acknowledgment of the effort required for behavior change

Reinforcement of success

Assistance with turning around any missteps along the way31

Additional adherence strategies can be found in the provider supplements to the CDC PrEP guidelines57; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-provider-supplement-2017.pdf

PrEP Discontinuation and Resumption

Patients should receive specific counseling on how to safely discontinue and restart PrEP. Discontinuation may be prompted by the individual’s personal choice, changed life circumstances, nontolerated side effects, toxicities, chronic nonadherence, or acute HIV infection. The protection provided by PrEP wanes over the 7–10 days following discontinuation; therefore, alternative methods to reduce risk of HIV acquisition should be discussed, including the emergent use of PEP in the event of a high-risk exposure.31

Discontinuation for any reason should be documented by the pharmacist. This should include HIV status at the time of discontinuation, reason for discontinuation, recent PrEP adherence, and reported sexual risk behavior. Under current regulations for pharmacist-provided PrEP, patients who wish to resume PrEP at any time after discontinuing it, will need to be under the care of a PCP.2 The patient must undergo all pre-PrEP steps, as outlined for first-time use.31

Summary: Section 4052.02 of the California Business and Professional Code—

Pharmacist-Provided PrEP2

Section 4025.02 allows pharmacists to furnish at least a 30-day supply, and up to a 60-day supply, of PrEP if the following conditions are met:

The patient is HIV-negative, as documented by a negative HIV test result obtained within the previous 7 days using an FDA-approved HIV antigen/antibody test or antibody-only test or from a rapid, point-of-care fingerstick blood test.

If the patient does not provide evidence of a negative HIV test in accordance with this requirement, the pharmacist shall order an HIV test. Note: Per CDC PrEP guidelines, clinicians should not accept patient-reported test results or documented anonymous test results.31

If the test results are not transmitted directly to the

pharmacist, the pharmacist shall verify the test results to the pharmacist’s satisfaction.

If the patient tests positive for HIV infection, the pharmacist or person administering the test shall direct the patient to a PCP and furnish a list of providers and clinics in the region.

The patient does not indicate any signs or symptoms of acute HIV infection on a self-reported checklist.

The patient does not report taking any contraindicated medications.

The pharmacist provides counseling to the patient on the ongoing use of PrEP, which may include education about side effects, safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding, adherence to recommended dosing, and interval monitoring for adverse events, PrEP adherence, relevant drug-drug interactions with concurrent medications, behavioral risk-reduction practices, and CDC guideline-defined interval laboratory testing pertaining to HIV, STIs, pregnancy, and renal function (eCrCl).31

Note: Section 4052.02 of the California Business and Professions Code also states that the pharmacist shall not allow the patient to waive the consultation when picking up PrEP or PEP medications.2

The patient is advised that a pharmacist may not furnish more than a 60-day supply of PrEP to a single patient every 2 years (unless directed otherwise by a prescriber), and that the patient must be seen by a PCP to receive subsequent PrEP prescriptions.

The pharmacist documents pharmacist-provided services in the patient’s record within the record system maintained by the pharmacy. The pharmacist shall maintain records of PrEP furnished to each patient.

The pharmacist notifies the patient’s PCP that the pharmacist completed the requirements specified in this subdivision. If the patient does not have a PCP, or refuses consent to notify the patient’s PCP, the pharmacist shall provide the patient a list of physicians and surgeons, clinics, or other health care service providers to contact regarding ongoing care for PrEP.

To help pharmacists and other PrEP providers, the CDC has created supplements to keep track of important patient and provider steps before PrEP is prescribed57: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-provider-supplement-2017.pdf.

Beyond the First 60 Days

Although SB 159 states that a pharmacist may furnish up to a 60-day PrEP-regimen supply every 2 years for a given patient, no guidance is provided on the role of the pharmacist beyond these 60 days.2 This requirement underscores the importance of pharmacists building relationships with primary care prescribers, not only for referral at 60 days, but for coordinated patient support. Just as the patient’s first 2 months of PrEP use will be an important period during which the pharmacist provides patient education and support, and assesses for adherence issues and adverse events, good clinical practice would suggest integration of many of these aspects of the patient’s ongoing PrEP-related care into general pharmacy practice. The individual patient’s records, along with full documentation of pharmacist-provided PrEP services, should be transferred to the patient’s PCP, in order for the individual to continue PrEP.2 Patients who do not have a PCP experienced in PrEP provision can be referred to the American Academy of HIV Medicine database to locate a PrEP provider in their area58: https://providers.aahivm.org/referral-link-search?reload=timezone.

Keep in mind that patients who initially requested PrEP from their pharmacist—not their PCP—may have a higher level of comfort with and/or do not perceive stigma/discrimination on the part of the pharmacist. This trusted patient-pharmacist relationship should be maintained to support the patient’s well-being.

Transitioning From PrEP to HIV Treatment

as Prevention

Patients taking PrEP may become HIV-positive for various reasons. If detected at the first follow-up visit after PrEP initiation, it may be due to the patient having had undetectable acute infection at the time of pre-PrEP HIV testing (ie, within the window period). If detected at a later follow-up visit, this may indicate adherence issues.31 Rarely, some patients become HIV-positive despite good PrEP adherence: risk of HIV acquisition is not completely eliminated by high levels of adherence and may be due to drug-resistant viral strains.59

US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) HIV/AIDS guidelines recommend that upon laboratory confirmation of HIV infection in an individual on PrEP, the patient should transition from PrEP to an HIV treatment. An HIV treater (specialist or PCP) should be involved in determining ART selection and initiating therapy. Under new guidelines for rapid ART initiation (rapid ART; rapid start), there is no need to wait for additional laboratory results. A rapid ART strategy seeks to accelerate the time from HIV diagnosis to ART uptake and engagement in care, such that ART initiation begins on the same day as diagnosis (or as close as possible).44 Patients should be counseled on the benefits of early/continuous viral suppression for both themselves and their partners, with emphasis on undetectable=untransmittable (U=U). That is, maintenance of viral suppression (an undetectable viral load on ART), helps prevent the transmission of HIV to others. This is the basis of HIV treatment as prevention.60

PEP 101

PEP: Pharmacologic Considerations

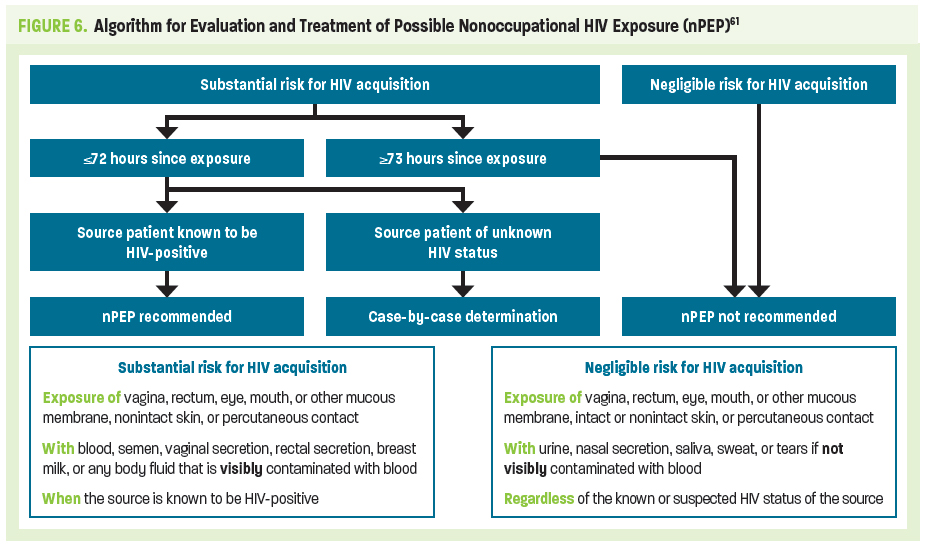

HIV PEP utilizes specific combinations of antiretroviral agents to prevent infection in appropriately identified and evaluated HIV-negative people who have had a single high-risk HIV exposure.9,63 Prescribing PEP should be considered an emergency intervention: PEP is not a substitute for appropriate, continuous use of PrEP in conjunction with behavioral risk reduction. It can be thought of as similar to dispensing the morning-after contraceptive pill.64 PEP is most effective when initiated as soon as possible—no more than 72 hours—after a potential HIV exposure.63

Occupational HIV exposure refers to high-risk events occurring in a health care setting, whereas nonoccupational HIV exposure refers to an isolated exposure to potentially infectious body fluids that occurs outside of a health care setting, most commonly through sexual activity or injection drug use. This discussion addresses nonoccupational PEP (nPEP) only.61

Although TDF and FTC are used in PEP, the clinical/pharmacologic concerns—and intensity of treatment—are more similar to treatment of established HIV infection, than to PrEP. PEP requires the use of either an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) or a boosted protease inhibitor (PI) in combination with both TDF and FTC. Current CDC PEP guidelines do not include use of TAF as a PEP-regimen component.61

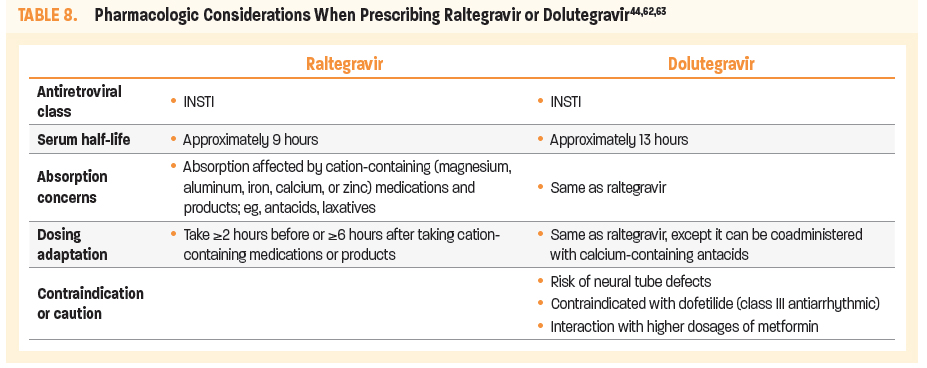

The DHHS PEP guidelines do not in general recommend 1 INSTI over the other (ie, DTG vs RAL), however, DTG may be preferred for its once-daily dosing.61,62,63 Please note that use of DTG should be avoided in early pregnancy because of the risk of neural tube defects due to drug exposure during the first 28 days of gestation. Similarly, nonpregnant women of childbearing potential who are sexually active or have been sexually assaulted and are not using effective birth control should not receive DTG.63 In either clinical scenario, patients should be prescribed RAL. Additional pharmacologic considerations when prescribing RAL or DTG as PEP are outlined in Table 8.

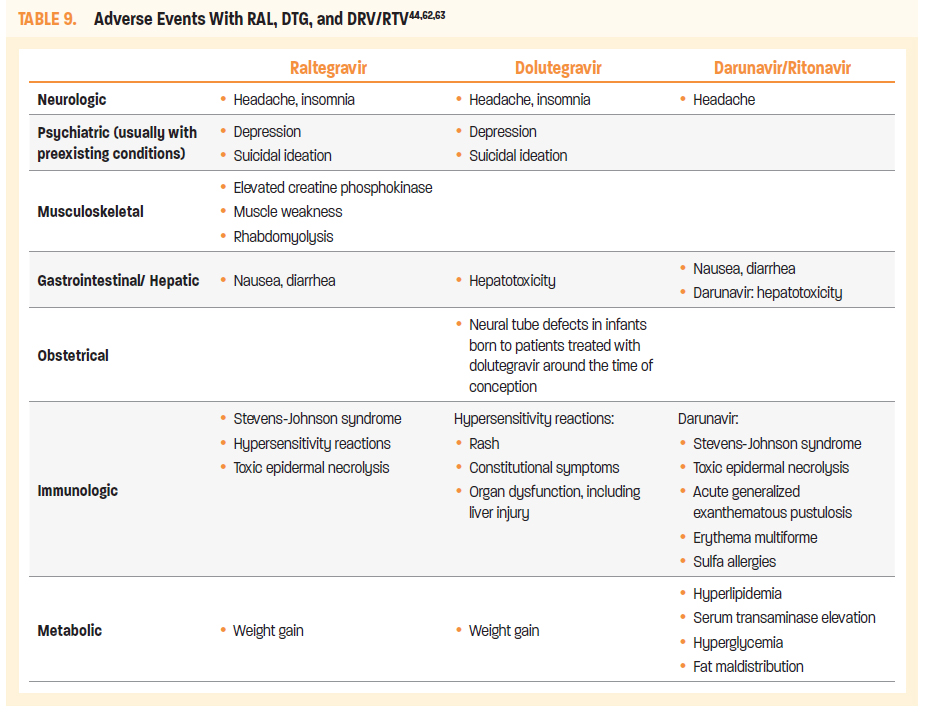

RAL and DTG are both associated with adverse events that include headache, insomnia, and weight gain.44,62,63 Both agents are also rarely associated with depression and suicidal ideation, although this usually occurs in patients who have preexisting psychiatric conditions. RAL may additionally cause fever, nausea, and diarrhea, and may be associated with more severe conditions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and rhabdomyolysis.

DTG is associated with additional adverse effects that include hepatotoxicity, hypersensitivity reactions (including rash, constitutional symptoms, organ dysfunction, and liver injury) and, as noted, potential for increased risk of neural tube defects in infants born to patients treated with DTG around the time of conception (Table 9).

TDF with FTC in combination with protease inhibitors DRV and RTV is an alternative 28-day PEP regimen for adult and adolescent patients.61

TDF 300 mg with FTC 200 mg once daily plus DRV 800 mg with RTV 100 mg once daily

RTV at the low dose of 100 mg is used as a pharmacokinetic booster for DRV; unboosted DRV is not a recommended alternative. The combination must be taken with food. Both DRV and RTV are inhibitors and inducers of multiple metabolic pathways. As a result, this combination with a serum half-life of 15 hours is contraindicated with certain sedative hypnotics, antiarrhythmics, sildenafil, and ergot alkaloids because of potentially life-threatening adverse effects. This combination can also affect the concentration of hormonal contraceptives.61

Additional adverse effects associated with DRV/RTV include nausea, diarrhea, and headache. DRV alone may cause hepatotoxicity, hyperlipidemia, serum transaminase elevation, hyperglycemia, and fat maldistribution. DRV has a sulfonamide moiety and should be used with caution in patients with sulfa allergies. Other more serious adverse effects have been reported with DRV, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, and erythema multiforme (Table 9).61

Pretreatment Determination of PEP Eligibility

As with HIV PrEP, HIV PEP prescribing is associated with several pretreatment requirements:

Conduct a comprehensive behavioral-risk assessment (sexual; injection drug use) and identify individuals at substantial risk of HIV exposure

Confirm HIV-negative status: select preferred HIV tests and/or accurately interpret HIV test results

Order appropriate laboratory tests to assess for PEP-associated risks

As PEP is most effective when initiated as soon as possible—no more than 72 hours—after a potential HIV exposure, these pretreatment evaluations should be performed immediately.61

Comprehensive Sexual (and Injection Drug Use) Risk Assessment61

During the initial postexposure evaluation, the pharmacist should determine the following:

Route/source of the potential HIV exposure

Timing and characteristics of the exposure; including sexual assault

Frequency of potential HIV exposures

Risk of other STIs (gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis), HBV, or HCV

Potential for current pregnancy (with pregnancy testing)

Needle-sharing during injection drug use and receptive anal intercourse are considered the highest per-act risks for nonoccupational HIV transmission. Insertive anal intercourse, insertive penile-vaginal intercourse, and oral sex carry relatively lower risks.61 Figure 6 is an algorithm for determining substantial HIV exposure. The information obtained through the comprehensive risk assessment will inform your use of the algorithm.

Confirmation of HIV-Negative Status

California SB 159 Section 4052.03 requires pharmacists to confirm HIV-negative status before furnishing PEP and/or to determine HIV status upon completion of a 28-day course of treatment.2 HIV-testing considerations, (as outlined for pre-PrEP assessment on page 8, in PrEP 101, Confirmation of HIV-Negative Status) also pertain to pre-PEP assessment, with special emphasis on clinical correlation of HIV-testing results and screening for signs and symptoms suggestive of acute/primary HIV infection (Table 5).

Importantly, if HIV test results are unavailable during the initial evaluation, initiation of PEP should be determined on the initial assumption that the potentially exposed patient is not infected.

When the HIV status of the potential source of exposure is unknown, if possible, that individual should consent to clinical evaluation and HIV testing using a 4th-gen antigen/antibody test.

If applicable and possible, the exposure source’s current ART and any information on treatment resistance should be taken into consideration. Pharmacists can make PEP treatment decisions without HIV testing of the source, depending on the informed consent of the exposed individual (under California law).2

Other Baseline Labs and Assessment for PEP-Associated Risks

As with HIV PrEP, pre-PEP laboratory assessment must be performed prior to treatment initiation. Again, critical labs include estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl), HBV serology, and pregnancy testing.

Additionally, if indicated by the comprehensive risk assessment, patients considered for PEP should be referred for timely STI testing and treatment. When appropriate, the patient should be offered routine prophylaxis for gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomoniasis. This is also an opportunity to address the need for routine vaccinations, eg, HAV, HBV, and human papillomavirus (HPV).61

California SB 159, however, does not provide specific roles for pharmacists in prescribing STI prophylaxis. Such care is deferred to PCPs or HIV treatment specialists with appropriate prescribing authorities.2

Pretreatment Prescriber Requirements

Having established the patient’s PEP eligibility—or having done so to the pharmacist’s satisfaction, if HIV results are not immediately available—the PEP provider’s additional pre-PEP requirements include the following clinical activities.2

Prescribe safe and effective PEP regimens for eligible persons without HIV infection

Educate patients about the selected PEP regimen to

maximize safe use

Provide counseling and effective contraception to women initiating PEP who do not wish to become pregnant; refer immediately for assessment of any reported sexual assault

Provide other patient-centered counseling regarding the following:

Medication-adherence to achieve and maintain protective

tissue levels

HIV risk reduction; including discussion and provision of prevention services referrals

Safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding

PEP-Regimen Selection, Prescribing61,63

A 28-day course of a 3-drug antiretroviral regimen should be prescribed for all persons requiring PEP. To optimize adherence, consideration should be given to minimizing side effects and number of doses per day and/or pills per dose; the 2 INSTI-based regimens are preferred:

TDF 300 mg with FTC 200 mg once daily plus raltegravir (RAL)

400 mg twice daily OR

TDF 300 mg with FTC 200 mg once daily plus dolutegravir (DTG)

50 mg once daily

Attention to a patient’s childbearing status or potential is crucial. Dolutegravir should be avoided within the first 28 days of gestation, or in women without current or reliable contraception.

DHHS guidelines recommend 3-drug ART in all nonoccupational PEP cases. However, in select cases, a 2-drug ART may be considered (eg, combination NRTIs or combination PI and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [NNRTI]) if there are concerns regarding potential adherence, toxicity, or costs.

Basic Medication Education

Basic medication-education components include the following:

Which PEP medication is being prescribed? How is it taken?

What is the dosing schedule?

How to manage missed doses

Common signs and symptoms suggestive of acute HIV infection (Table 5)

Common side effects associated with raltegravir, dolutegravir, darunavir/ritonavir (Tables 8 and 9)

What quantity will be dispensed?

Providing an entire 28-day course of the PEP ART and scheduling an early follow-up visit may increase the likelihood of adherence, especially if patients cannot return for multiple follow-up visits. Alternatively, the prescriber can provide a 3 to 7-day PEP starter pack. Additional follow-up visits allow pharmacists to:

Discuss baseline blood testing (including HIV results, if a rapid test was not used)

Assess for adherence and adverse effects, or change the PEP regimen, if indicated

Provide medication recommendations for symptomatic relief of side effects (eg, antiemetics)

Recommend pill boxes or other medication adherence aids (including smartphone apps)

Identify strategies to dose in line with a patient’s daily schedule

Ensure patient-pharmacist contact during PEP treatment

Patients should be instructed repeatedly on the importance of PEP-regimen adherence in preventing HIV infection.61

Summary: Section 4052.03 of the California Business and Professional Code—

Pharmacist-Provided PEP

Section 4025.03 allows pharmacists to furnish a complete 28-day course of PEP ART if the following conditions are met.2

The pharmacist screens the patient and determines the exposure occurred within the preceding 72 hours and the patient otherwise meets the clinical criteria for PEP consistent with CDC guidelines.

The pharmacist provides CLIA-waived HIV testing or determines that the patient is willing to undergo HIV testing consistent with CDC guidelines. If the patient refuses to undergo HIV testing, but is otherwise eligible for PEP under this section, the pharmacist may furnish PEP.

The pharmacist provides counseling to the patient on the use of PEP consistent with CDC guidelines, which may include education about side effects, safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding, adherence to recommended dosing, and the importance of timely testing and treatment, as applicable, for HIV and STIs. The pharmacist shall also inform the patient of the availability of PrEP after a full 28-day PEP course for persons who remain HIV-negative and are at substantial risk of acquiring HIV.

Note: Section 4052.02 of the California Business and Professions Code also states that the pharmacist shall not allow the patient to waive the consultation when picking up PrEP or PEP medications.2

The pharmacist notifies the patient’s PCP regarding PEP treatment. If the patient does not have a PCP, or refuses consent to notifying the patient’s PCP, the pharmacist shall provide the patient a list of physicians and surgeons, clinics, or other health care service providers to contact regarding follow-up PEP-related care.

Transitioning From PEP to PrEP

PEP is indicated only for potentially exposed patients who are HIV-negative at initial PEP evaluation. If the patient has documented HIV-negative status (preferably using a 4th-gen antigen/antibody test) upon completion of a 28-day course of PEP, s/he can be transitioned from PEP to PrEP without any gap in treatment.31,61 Patients who are at frequent, recurrent risk of HIV exposure, or require sequential or near-continuous courses of PEP, should be offered 1 of the 2 FDA-approved PrEP ART regimens in conjunction with behavioral risk–reduction counseling and interventions. Patients should receive full PrEP education and be reassessed and counseled regarding medication adherence—despite their successful completion of PEP.61

PEP Failure and Transitioning From PEP to HIV Treatment as Prevention61

If use of PEP fails to prevent HIV infection, patients may experience signs and symptoms of acute/primary, or early, HIV.30 Patients should be instructed during the initial PEP evaluation about such manifestations, as listed in Table 5. Should any signs and symptoms related to acute HIV infection occur during the 28-day PEP course or anytime within 1 month after PEP concludes, patients should return for further evaluation and possible referral to an HIV treatment specialist. If a patient is taking PEP ART involving 3 agents at the time of detected infection, the ART should be continued until patient evaluation and treatment planning with an experienced HIV treatment specialist are completed.

Embracing Sexual Wellness and Discussing HIV Risk

Sexual Health Assessment

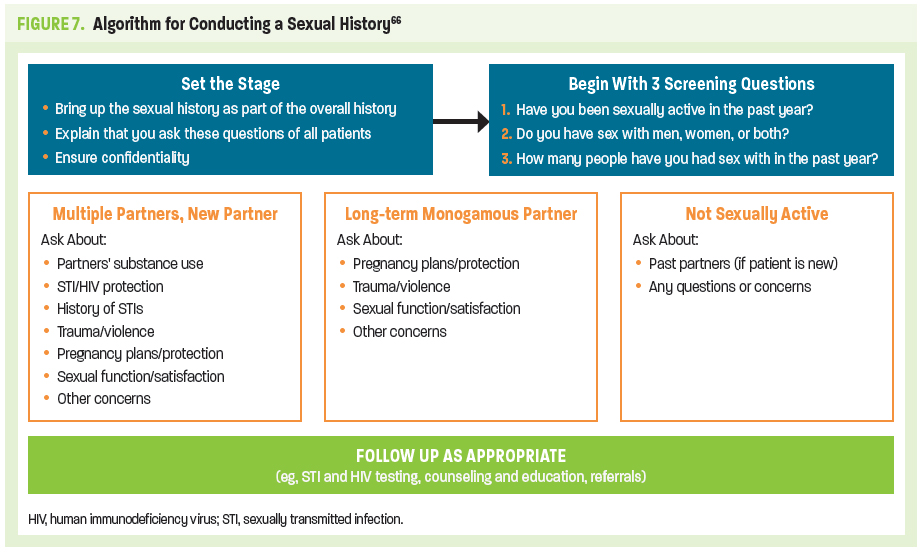

A comprehensive sexual health assessment is critical to determining an individual’s need for PrEP, as HIV risk may be associated with numerous personal, partner, relationship, social, cultural, network, and community factors.31 Many health care providers do not ask about same-sex behaviors because of personal discomfort or anticipated patient discomfort. Further, patients often do not disclose sexual behaviors because of perception of stigma or fear of judgment.

Frank, nonjudgmental questions about sexual behavior, alcohol use, and illicit drug use should be asked.31 The CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines recommend the following risk-behavior questions, known as The 5 Ps65:

Partners: In the past 12 (or 3, or 6) months, with how many partners have you had sex? Are they men, women, transgender women, and/or transgender men?

Practices: To understand your risks for STIs, I need to understand the kind of sex you have had recently. Do you have oral sex, vaginal sex, anal sex? For MSM: are you a top (insertive), bottom (receptive), or versatile (insertive or receptive)?

History of STIs: Have you ever had an STI? When? Have any of your partners had an STI?

Protection from STIs: How often do you use condoms? What do you do to protect yourself from HIV and STIs?

Pregnancy plans: Do you wish to prevent pregnancy? Are you using contraception; if so, what type?

Clinicians can refine their history-taking skills by making patients feel more comfortable and, therefore, potentially more open: use neutral and inclusive terms; avoid assumptions based on age, appearance, marital status, or other factors; and ensure that patients share an understanding of the terms used. (Figure 7).67,68 For additional training on opening a sexual health dialogue, go to https://realcme.com/learner/course/2591 or https://realcme.com/learner/course/2508.

Before starting, consider informing the patient about the routine nature of taking a sexual-health assessment with the following statement:

“I am going to ask you a few questions about your sexual history. I ask these questions at least once a year of all my patients because the information is very important for your overall health. Everything you tell me is confidential, as part of our patient-provider relationship. Do you have any questions before we start?” If patients want to know the reasons/importance of a sexual health assessment, consider using the following statements69:

Sexual health is important for overall emotional and physical health

We ask these questions every year because it is common for people’s sexual behaviors and partners to change over time

As you may know, sexual activity without protection can lead to STIs. These diseases—especially syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia—are very common and often do not cause any symptoms. If we do not catch and treat these diseases, they can affect general health and well-being

These questions can also help guide our conversation about

how you can protect yourself from STIs, unwanted pregnancy, or other issues that may concern you. It will also give you an opportunity to talk about problems with, or changes in, sexual

desire and functioning

Our discussion may help us identify other health needs (eg, additional lab testing; vaccinations) or resources you may need as part of your lifestyle (sexual- or nonsexual-related)

For pharmacists who are starting to build a PrEP/PEP provider practice, consider establishing a safe and supportive environment in which to discuss a patient’s personal health issues, one that also promotes confidentiality.70

Several resources are available to help pharmacists develop a comprehensive sexual-history dialogue with patients:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Guide to Taking a Sexual History70

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/sexualhistory.pdf

National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. Taking Routine Histories of Sexual Health: A System-Wide Approach for Health Centers66

https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/publication/taking-routine-histories-of-sexual-health-a-system-wide-approach-for-health-centers/

TargetHIV. Sexual History Taking Toolkit67

https://targethiv.org/library/sexual-history-taking-toolkit

US Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the US – 2017 Update Clinical Providers’ Supplement57

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-provider-supplement-2017.pdf

Communicating With Transgender Persons

In addition to the empathy and respect that you will show all patients participating in sexual-history discussions, there may be special considerations when taking sexual histories with transgender people, a high-risk population that is underrepresented among PrEP users. The following points are taken from the National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center and may also be helpful when taking sexual histories from other individuals, especially with regard to gender pronouns.66

Make sure you have established a good rapport with the patient before asking about sexual practices (or doing a physical exam)

Be sure to use the patient’s preferred name during conversations. This will not necessarily be the name that appears on insurance and medical records.

Ask what pronoun(s) your patient prefers. This is best done on an intake form but may also be needed during the clinic visit. Some people change their personal pronoun preference

Many transgender people want you to use the pronoun that matches their gender identity. For example, a transgender woman would like you to use “she/her”

Some transgender or gender-nonconforming people may ask you to use “ze” or “they,” or to try to avoid using any pronouns

Discussing Risk of HIV Acquisition Through Injection Practices

The US Preventative Services Task Force recommends that all health care providers be aware of signs and symptoms associated with injection drug use. Brief risk-behavior assessment questions that address this concern include the following31:

Have you ever injected drugs that were not prescribed to you

by a clinician?

(If yes), When did you last inject nonprescribed drugs?

In the past 6 months, have you injected by using needles, syringes, or other drug-preparation equipment that had already been used by another person?

In the past 6 months, have you been in a methadone or other medication-assisted substance use disorder treatment program?

Answers from these questions may help you determine if additional resources are needed for patients who inject drugs or have other high-risk substance-use related concerns or behaviors. Such resources include harm-reduction (behavioral risk reduction) programs and services, medication-assisted treatment (eg, buprenorphine), inpatient or residential drug treatment programs, or relapse-prevention services (eg, 12-step programs or mental health/behavioral support programs).31,57 The website for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (https://www.samhsa.gov) is a valuable resource for locating treatment facilities and programs for substance use, opioid treatment, buprenorphine access, and behavioral and mental health.71

HIV-Prevention Implementation and Advocacy

The California Model of Pharmacy-Based HIV Prevention

With the approval of SB 159, governmental entities—including the California State Board of Pharmacy and the California Department of Public Health (CDPH)—have been faced with drafting emergency regulations that outline how the bill will be implemented. Importantly, action is needed with regard to training requirements and fee schedules.72 As of July 5, 2020, the California State Board of Pharmacy proposed regulations in support of SB 159, including training requirements for interested pharmacists and recordkeeping requirements for pharmacists who complete the training program (the only SB 159–related emergency regulation approved at the time of writing).73

Contemporaneously, local HIV/AIDS clinics and wellness organizations have been working to increase awareness among pharmacists and encourage uptake of PrEP/PEP provision. Of note, some pharmacies with collaborative practice agreements (including Mission Wellness Pharmacy in San Francisco, California, and Kelley-Ross Pharmacy in Seattle, Washington) already provide PrEP without an outside prescription.74 Mission Wellness Pharmacy is a one-stop PrEP program that allows pharmacists to initiate and furnish PrEP directly to patients as part of a demonstration project with the San Francisco Department of Public Health. Kelley-Ross Pharmacy is able to offer pharmacist-driven PrEP provision and HIV-prevention services through not only collaborative practice agreements, but also through Washington State legislation allowing pharmacists to bill for patient-care services, including monthly patient evaluations, without a limit on length of time the patient can remain under the care of a pharmacist.75

Building In-Pharmacy Infrastructure and Capacity

A commentary recently published in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association provides recommendations for implementing a community-based PrEP program that reflects the previously discussed San Francisco and Seattle models. That publication also provides recommendations for how community pharmacies can integrate PrEP implementation into their existing services.76

Those recommendations for modifying pharmacy infrastructure to accommodate PrEP/PEP services include the following:

Set up logistics for on-site laboratory testing or for sending out laboratory specimens

Order CLIA-waived rapid tests

Provide physical space within the pharmacy for collecting laboratory specimens

Train staff regarding on-site (“one-stop PrEP”) and/or off-site specimen collection and handling

Consider use of an on-site phlebotomist

Manage laboratory test results

Adapt pharmacy workflow

Establish private/confidential spaces for sensitive discussion of test results

Consider installing modular-ready private counseling rooms

Assign specific pharmacy staff to accommodate walk-in requests for lab results

Establish communication protocols and methods

Determine how confidential information will be shared among team members, patients, and referring providers or health departments in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements77

Set up online portals, secure e-mails, text messages, apps, and shared electronic medical records (EMRs), which can save time and staff resources

Provide and monitor pharmacist education and hands-on training, including training of pertinent auxiliary pharmacy staff

Set up a pharmacist-specific training program and, as appropriate, auxiliary-staff training

Require pharmacists to demonstrate competency in delivering PrEP and PEP per national guidelines, inclusive of sexual-health counseling, comprehensive risk-appropriate prevention strategies, laboratory testing and interpretation, and navigation of insurance benefits and patient-assistance programs

Set realistic time frames for implementation of new work processes and attainment of target number of patient visits

Provide pharmacist and staff feedback, ongoing training,

and monitoring

Part of ensuring the future success of offering PrEP and PEP in the community is engaging and supporting pharmacists who can educate stakeholders and break down barriers to PrEP access.74 Successful programs are based on trust, relationships, and partnerships in the community.78 Instead of waiting 2 to 3 weeks for PrEP, patients can easily participate in a 45-minute conversation with the pharmacist that gets them the PrEP they need.

Your Patient’s Advocate: Coordination of Care, Financial-Assistance Resources, and Pharmacist Resources

While amendments set forth in California SB 159 expand the pharmacist’s scope of practice to include furnishing PrEP and PEP, they do not address access or insurance coverage for initial HIV testing, required to establish the need for pharmacist-directed provision of PrEP or PEP, or for guideline-based interval laboratory testing.2

With SB 159 also requiring the pharmacist to provide information regarding financial assistance resources, it’s important to know about programs such as Ready, Set, PrEP a nationwide program launched by the CDC in December 2019 to make PrEP available at no cost to individuals who lack prescription drug coverage and meet the following requirements2,10:

Test negative for HIV AND

Have a valid prescription from a health care provider AND

Do not have health insurance coverage for outpatient

prescription drugs

Although Ready, Set, PrEP ensures access to PrEP for qualifying individuals, it also stipulates that the costs for necessary clinic visits and laboratory testing may vary based on income.10,79 Patients interested in PrEP or PEP who are uninsured or underinsured can visit the CDPH Office of AIDS PrEP Assistance Program resources webpage for more information. This site offers numerous resources and forms for providers, as well. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DOA/Pages/OA_adap_resources_prepAP.aspx#

Additionally, Gilead’s Advancing Access® program is another patient assistance program available for both insured and uninsured patients (http://www.gileadadvancingaccess.com). While Gilead provides financial and access assistance to patients through Ready, Set, PrEP and the California PrEP Assistance Program, patients can also independently apply for these programs.10,79 Of particular note, it is uncertain at time of writing whether these patient assistance programs will apply to generic TDF/FTC.

Concluding Comments

HIV Prevention: The Pharmacist as Educator, Provider, and Advocate

This monograph has outlined the pharmacist’s role in the provision of PrEP and PEP, as based on California Senate Bill 159 and subsequent additions/revisions to the California Health and Professions Code and Welfare and Institutions Code. Outstanding issues to be addressed before pharmacists can fully embrace these new roles include reimbursement for pharmacist-provided care. This is an issue that transcends pharmacists’ roles in PrEP/PEP provision and encompasses advanced-level clinical pharmacy services, as introduced with Senate Bill 493.

The full implementation of a pharmacy infrastructure that supports the provision of PrEP/PEP will remain another challenge for many. Successful business models will most likely involve PrEP/PEP provision as part of a comprehensive array of clinical services offered by pharmacies that are supported by existing Board of Pharmacy regulations. Diversification of services, and thus diversification of patients served, is likely to bring in additional business that can be billed, thereby supporting overall clinical services—and the pharmacy’s bottom line.

The accessibility of pharmacy professionals makes pharmacy settings an ideal entry point for people at risk for HIV to initiate prophylactic therapy to prevent HIV infection. The pharmacist’s role as HIV-prevention educator, PrEP/PEP provider, and patient advocate has the potential to grow into a greater presence within the local public-health sphere. This expansion of the pharmacist’s scope of practice can potentially help build strong relationships with patients, PCPs, and community-based patient-support services, while establishing the pharmacist as an essential and reliable resource. Provision of PrEP and PEP services by well-trained and well-placed pharmacists can be a driving force in attaining the goal of zero new HIV infections.

Q & A Forum

With Dr. Lucas Hill

If you have additional questions related to SB 159, clinical or pharmacologic aspects of PrEP or PEP, resources for you or your patients, or implementation of PrEP and PEP services at your pharmacy, visit the Q & A Forum at: www.prepforcalipharms.com. If an answer isn’t readily available, you’ll receive a personalized response from faculty member, Lucas Hill, PharmD, BCACP, AAHIVP, UC San Diego Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Resources

For PEP/PrEP clinical resources, including practice guidelines, organizations, patient resources, and suggested readings, visit

www.ExchangeCME.com/PrEPResourcesforPharms.

List of Abbreviations

Ab antibody

Ag antigen

AHI acute HIV infection

AIDS acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CDPH California Department of Public Health

CI confidence interval

CLIA Clinical Laboratory Improved Amendments

DAA direct-acting antiviral

DDI drug-drug interaction

DHHS US Department of Health and Human Services

DNA deoxyribonucleic acid

DRV darunavir

DTG dolutegravir

EBR/GZR elbasvir/grazoprevir

eCrCl estimated creatinine clearance

EMR electronic medical record

GLE/PIB glecaprevir/pibrentasvir

FDA US Food and Drug Administration

FEM-PrEP Preexposure Prophylaxis Trial for HIV Prevention Among African Women

FTC emtricitabine

Gen generation

HAV hepatitis A virus

HBV hepatitis B virus

HCV hepatitis C virus

HDL high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

HIPAA Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

HIV human immunodeficiency virus

HPV human papillomavirus

IA immunoassay

IgG immunoglobulin G

IgM immunoglobulin M

IAS–USA International Antiviral Society–USA

IDU injection drug use

iPrEx Iniciativa Profilaxis Pre-Exposición [Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative]

INSTI integrase strand transfer inhibitor

IRR incidence rate ratio

LDL low-density lipoprotein

MSM men who have sex with men

NAAT nucleic acid amplification testing

NNRTI nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

NI noninferior

nPEP nonoccupational PEP

PCP primary care provider

PCR polymerase chain reaction

PEP postexposure prophylaxis

PI protease inhibitor

PLWH people living with HIV

PrEP preexposure prophylaxis

PY person-years

PWID people who inject drugs

RAL raltegravir

RNA ribonucleic acid

SOF/LDV sofosbuvir/ledipasvir

SOF/VEL sofosbuvir/velpatasvir

STI sexually transmitted infection

TAF tenofovir alafenamide

TDF tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

TDF2 Botswana TDF/FTC Oral HIV Prophylaxis trial

WHO World Health Organization

References

- Health Resources and Services Administration. National HIV/AIDS Strategy: Updated to 2020. Last reviewed November 2017. https://hab.hrsa.gov/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program/national-hivaids-strategy-updated-2020. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- California Legislative Information. SB 159 HIV: Preexposure and Postexposure Prophylaxis. October 2019. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB159. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV Basics: US Statistics. Updated June 30, 2020. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics. Accessed July 2, 2020.

- Policy, Planning and Strategic Communication. Dear colleagues: information from CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/dear-colleague/dcl/050720.html. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Roser M, Richie H. HIV/AIDS. Last updated November 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/hiv-aids. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(9):1-77.

- Azar AM II. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for America. February 5, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/blog/2019/02/05/ending-the-hiv-epidemic-a-plan-for-america.html. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. 2016; https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv/9/treatment-goals. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). Updated May 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/prevention/prep-and-pep.html. Accessed July 11, 2020.

- S. Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS). Ending the HIV epidemic: Ready, Set, PrEP. Updated June 26, 2020. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/prep-program. Accessed June 28, 2020.

- Choopanya K, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. 2013;381(9883):2083-2090.

- Anderson PL, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(151):151ra125.

- Kazi DS, et al. PrEParing to end the HIV epidemic—California’s route as a road map for the United States. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2489-2491.

- Hess KL, et al. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238-243.

- Goldstein RH, et al. Being PrEPared—preexposure prophylaxis and HIV disparities. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(14):1293-1295.

- Siegler AJ, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):841-849.

- HIV. Figures. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2018—United States and 6 dependent areas. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-31/content/figures.html. Accessed August 2, 2020

- Cahill S, et al. Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS Care. 2017;29(11):1351-1358.

- California Legislative Information. SB 493: Pharmacy Practice. October 1, 2013. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140SB493. Accessed June 27, 2020.

- Life-saving naloxone from pharmacies. Updated August 6, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/naloxone/index.html. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- Newman TV, et al. Optimizing the role of community pharmacists in managing the health of populations: barriers, facilitators, and policy recommendations. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(9):995-1000.

- Kibicho J, Owczarzak J. Pharmacists’ strategies for promoting medication adherence among patients with HIV. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2011;51(6):746-755.

- Hill LA, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the management of people living with HIV in the modern antiretroviral era. AIDS Rev. 2019;21(4):195-210.

- Tseng A, et al. Role of the pharmacist in caring for patients with HIV/AIDS: clinical practice guidelines. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2012;65(2):125-145.

- Core Indicators for Monitoring the Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative. December 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/ehe-core-indicators/cdc-hiv-ehe-core-indicators-2019.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- The science of HIV and AIDS–overview. Last updated October 2019. https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-science/overview. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Cummins NW, Badley AD. Making sense of how HIV kills infected CD4 T cells: implications for HIV cure. Mol Cell Ther. 2014;2:20.

- Understanding HIV/AIDS: The HIV life cycle. Updated July 1, 2019. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv-aids/fact-sheets/19/73/the-hiv-life-cycle. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- Liu Y, Tran N. Best practices for HIV-1/2 screening: when to test and what to test. https://blog.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/labbestpractice/?s=best+practices+for+HIV-1%2F2+screening. Accessed August 12, 2020.

- Patel P, et al. Rapid HIV screening: missed opportunities for HIV diagnosis and prevention. J Clin Virol. 2012;54(1):42-47.

- US Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States—2017 Update (A Clinical Practice Guideline). March 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Last reviewed May 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/prevention/prep.html. Accessed July 22, 2020.