Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Implementing a Mindful Practice in Pharmacy

INTRODUCTION

Excellent patient care requires not only the knowledge of pharmacotherapy to treat disease, but also the ability to form relationships with patients and their families, recognize and respond to emotionally demanding situations, and make decisions under uncertainty.1 A professionals’ own personalities, personal history, family and cultural background, values, biases, attitude and emotions influence their reaction to patients.2 This requires a health care professional to have the self-awareness to distinguish their values and feelings from those of their patients, recognize when there is a lack of good decision making on their own part, and be attentive to the emotions of those who work with them. Self-reflection enables clinicians to listen attentively, recognize their own errors, and clarify their personal values so that they can act with compassion, competence and insight.3

Unrecognized emotions and attitudes can adversely affect patient care and mindful practice, which is fundamental to recognizing and responding to these unconscious thoughts and behaviors. Mindfulness implies a state in which the practitioner can observe not only the patient situation but also his or her own reactions to it.4 A mindful practitioner can see a situation from several angles at the same time. This type of practice is especially helpful when dealing with challenging clinical situations, difficult relationships with patients and families, and in recognizing the need for self-care.1 Research suggests that a mindful practice is associated with better communication, better quality of care (fewer errors, increased empathy), less implicit racial and gender bias, and greater clinician well-being (e.g., lower burnout).5

DEFINING MINDFUL PRACTICE

Mindful practice means being attentive, on purpose, to one’s own thoughts and feelings during everyday clinical practice.1 It means being simultaneously attentive to external data as well as to internal data—the clinician’s own thoughts, feelings, and inner states.1 A lapse in awareness or concentration can have serious consequences related to patient care. When we practice without purposeful awareness, we are not being mindful but rather mindless. An example of mindlessness is the practice of reporting findings that were not actually observed, because “they must be true.”1 For example, when a patient is late on their refills and we assume incorrectly that they are being non-adherent would be defined as mindless if the clinician did not take the time to properly investigate the circumstances. Taking the time to ask the patient and coming to the conversation with curiosity, will allow the clinician to see all the different factors that may have affected the patient’s late refill status. Lapses in awareness of our own perceptions and biases can directly affect the patient’s welfare and may include avoidance, overreactions, poor decisions, misjudgments and miscommunications on the clinician’s part.1

Characteristics of a Mindful Practice

The goals of mindful practice are to become more aware of one's own mental processes, listen more attentively, and recognize bias and judgments.3 Table 1 lists the characteristics of a mindful practice.

| Table 1. Characteristics of a Mindful Practice3 |

| Characteristic |

Explanation |

| Active observation of oneself, the patient and the problem |

Recognizing all aspects of patient care including one’s own emotions and behaviors |

| Peripheral vision |

Cultivating awareness not only of the correct course of action but also the factors that could cloud the clinician’s decision-making process |

| Pre-attentive processing |

Being aware of things before they are named, categorized, or organized in one’s mind |

| Curiosity |

Being curious about the unknown and acceptance of having an imperfect understanding of other’s viewpoints |

| Seeing the world as it is versus how you think it should be |

Unfounded certainty and ignoring contradictory data cause one to see things not how they are, but how they choose to see them (which may be incorrect) |

| Willingness to set aside prejudices |

Framing a situation without values and personal biases |

| Adopting a beginner’s mind |

Seeing a familiar situation through new eyes |

| Humility to tolerate one’s own incompetence |

Allowing awareness of one’s own areas of ignorance without personal judgment |

| Connecting the knower and the known |

Acknowledging the bond between clinician and patient which fulfills the basic need for human connection |

| Compassion based on insight |

Responding with empathy based on an understanding of the patient’s experience rather than making assumptions about the patient |

| Presence |

Being in the moment; the opposite of detachment |

Levels of Mindfulness

Getting to know yourself and becoming mindful is about exploring yourself on a conscious level, knowing your conscious thoughts and perceptions and how they drive you. It is also about digging into the unconscious to uncover what is ultimately driving your behavior, thoughts and emotions. In order to develop a mindful practice, most clinicians will need to practice and move through various levels of mindfulness. Each level supersedes the previous level by incorporating reflection and self-awareness and thereby allowing the clinician to move onto the next level of awareness. Keep in mind that all clinicians may not start at the lowest tier and depending on the individual, will move through the levels at varying paces.

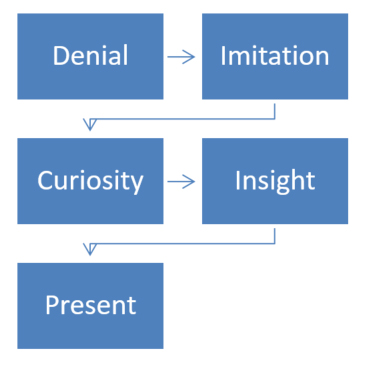

At the extreme of mindless practice, the clinician's response is denial. By making the problem external, the clinician avoids responsibility and comprehends and explain things in ways that are contrary to the evidence.3 Consider the clinician who refuses to take responsibility for a mistake even though all evidence points to the contrary. At the next level the clinician accepts responsibility for his/her actions but there is no self-reflection. Instead, the clinician acts based on the established rules of society or what they have learned from role models, but does not conceptualize their own feelings or thought processes and incorporate them into their actions.3 Consider an employee who follows company policy but does not reflect on why that policy is important or what it means to other team members or patients. A clinician will then move on to include curiosity about feelings, thoughts, and behaviors without attempting to suppress or label them as good or bad.3 By including emotions with personal knowledge, the clinician now has more tools available to promote a better standard of patient care. The next level allows the clinician to use insight to understand the nature of the problem, conceptualizing how to solve it, and then incorporating their own knowledge to contribute to a solution.3 Finally, practicing at the highest level of mindfulness, the clinician will be able to use their insight to relate to other similar problems, reflect on the process that was used in the past, learn from new experiences and mistakes and in essence fulfilling the true meaning of being present in any situation.3 Figure 1 outlines the steps of the varying levels of cultivating a mindful practice.

Figure 1. Levels of Mindfulness3

CULTIVATING MINDFULNESS IN PRACTICE

While it is evident that self-awareness is a necessary ingredient in developing and maintaining excellent patient care, achieving a state of moment-to-moment self-awareness in a chaotic environment requires considerable and concentrated effort. Self-awareness means being aware of your feelings and their impact on your behaviors. Research demonstrates that hidden feelings and attitudes can be harmful to patients and exhibited during patient-clinician interactions even if unintentional.2 The goal of developing self-awareness is to identify potentially harmful responses and, in turn, to actively work to change them. Developing awareness of interfering emotions and beliefs is a powerful way to enhance patient care and foster excellent communication skills.

Developing Emotional Awareness

Clinicians may not have had adequate training particularly in dealing with the most difficult of all patients. Consider the following scenario that commonly happens in patient care. A pharmacy patient with chronic pain, comes into your pharmacy seeking opioids and/or benzodiazepines. This is a well-known setup for the pharmacist or pharmacy technician to exhibit negative reactions to the patient wherein a harmful relationship develops.6 Harmful responses vary along a spectrum from passively filling the medication as the easiest way to get rid of the patient quickly, falsely telling the patient the medication is out of stock, or blatantly refusing to fill any more prescriptions for this “difficult” patient. While often understandable, negative reactions to the patient are nonetheless a huge deterrent to effective care. How can one best deal with what are often subconscious and therefore mostly reflexive reactions on their part? The answer is to make yourself aware of your feelings and their impact on your behaviors with the patient.7

To identify any difficulties the clinician is having one must become aware of all the emotions experienced. Cultivating a high level of emotional intelligence will give the clinician the ability to identify and manage one’s own emotions, as well as the emotions of others.8 Emotional intelligence is generally said to include at least three skills: emotional awareness, or the ability to identify and name one’s own emotions; the ability to utilize those emotions and apply them to tasks like thinking and problem solving; and the ability to manage emotions, which includes both regulating one’s own emotions when necessary and helping others to do the same.8 Table 2 list some ways to foster emotional awareness.

| Table 2. Activities to Foster Emotional Awareness7 |

| Read stories of patients’ courage in the face of severe pain and/or suffering |

| Read emotion-laden biographies and fiction |

| Watch movies with considerable emotion |

| Engage with emotionally expressive people |

| Engage in emotionally relevant (to you) music and art |

| Talk about your positive and negative reactions to others and listen while others do the same with you |

| Journal to describe the emotion and the behavior that followed it |

| Meet regularly with team members to discuss thoughts and emotions about difficult cases/patient encounters |

By doing these exercises, one should be able to identify patterns in repeated behaviors exhibited by emotions. When you recognize an emotion that leads to a counterproductive behavior on your part what is the next step? The key is to recognize it, acknowledge it and act upon it. Here is an example, “I am feeling angry when this patient tries to get her narcotic prescription filled early every month and, in the past, I would have reacted by losing patience and raising my tone of voice with the patient.” Each time this happens say to yourself, “Now that I recognize my (negative reaction), it’s up to me to decide if I want to continue to act the same way.” Repeatedly acknowledging something one wants to change in their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors often leads to improvement by raising it to a conscious level and making a rational decision what to do instead of merely reacting to emotions.7 This is very rewarding (but difficult work) for the clinician and improving your emotional intelligence will benefit all your relationships both professional or personal.

Strategies to Enhance Mindfulness

Group learning experiences can help to promote self-reflection and cultivate personal awareness. Small group settings for clinicians to present difficult situations for group discussion can result in insights that might inform future practice.1 Krasner et al.8 conducted a study to determine whether an intensive educational program in mindfulness, communication, and self-awareness was associated with improvement in primary care physicians' well-being, psychological distress, burnout, and capacity for relating to patients. Group activities included incorporating mindfulness meditations, narratives about meaningful clinical experiences, and appreciative inquiry to explore successful ways to work through difficult clinical situations. These activities were shown to lead to less burnout, lower psychological distress, greater empathy and improved patient-centered orientation to care.8 The following are some suggestions for small group activities that can promote mindful practice in the clinical setting (Table 3). As well as group activities, some individual activities can help foster reflection and mindfulness in a clinician (Table 4).

| Table 3. Group Activities to Promote Mindfulness1 |

| Activity |

Description |

| Mindful practice workshops |

Uses mediation, narrative, appreciative interviews and discussion |

| Support groups |

Promotes balance between the human and technical aspects of health care by sharing difficult/challenging situations |

| Family of origin groups |

Drawing genograms to help participants learn about influences family and culture have on their values and attitudes |

| Literature in medicine groups |

Using published writings to explore the human dimensions of health care |

| Case conferences |

Presenting cases to explore the moment-to-moment actions taken during a challenging clinical encounter |

| Table 3. Individual Activities to Promote Mindfulness1 |

| Description |

Activity |

| Video review |

Review video sessions with difficult clinical encounters |

| Peer evaluations |

Evaluation of work habits and interactions within the team |

| Journaling |

Recording of daily emotions and resulting behavior |

Mindful practice refers not only to reflection on one’s actions but goes one step further by emphasizing habits of the mind during actual practice. While extremely purposeful activities to promote a mindful practice, the activities in the above tables may not translate into gained insight in the moment-to-moment aspects of daily practice.1 It is important to realize that mindful practice not only involves the social and emotional interactions, but also the cognitive processes of data gathering and decision making, as well as the technical skills involved in practicing.1 The following are some additional activities that one can utilize to practice at a higher level of mindfulness.

- Mindful practice usually involves stillness.1 Meditation can be a method to concentrate on becoming still and being aware of potentially distracting thoughts, feelings, and preconceptions; and help to focus on being more attentive to the patient.1 Daily meditative practice is an increasingly helpful habit to invoke a state of calm attentiveness throughout an often chaotic workday.

- Priming. To be more present, a clinician needs to observe what they do during practice. This could be as simple as taking a deep breath before entering the patient’s room or making eye contact with the patient rather than a chart or computer screen.1 These techniques should be used to help bring focus to the present. The clinician should pay attention not only to the patient but also their own thoughts and feelings during the encounter and use this information to enhance clinical capabilities.

- Thinking out loud. A clinician can talk through a challenging situation with a colleague by describing the observations and clinical reasoning utilized or putting them down on paper in the form of a narrative.1 This allows for examination of their own thinking processes and emotional reactions by hearing the story from a third person point-of-view and results in a deeper level of reflection versus just moving forward with problem solving.1 Thinking out loud in the presence of others allows for recognition of one’s own ignorance, biases, and predispositions and can lead to more deliberative responses rather than mindless reactions.1

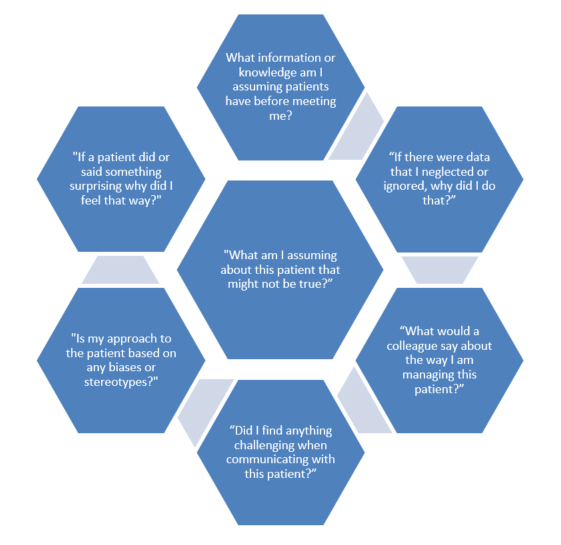

- Asking reflective questions.Clinicians should adopt a habit of self-questioning. Reflective questions explore the inner landscape and this internal dialogue can contribute to a mindful practice.1 Examples of reflective questions are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Reflective Questions1

The goal of mindful practices should be developing habits of reflection, self-questioning, and awareness in the moment during clinical practice. With continued practice at developing these habits, they will eventually become second nature to the clinician.

REDUCING BIAS THROUGH MINDFUL PRACTICE

There is increasing evidence that healthcare providers, like the population at large, hold implicit stereotypes and prejudices against members of stigmatized groups (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities, gay and lesbian, obese, lower social class), which can contribute to healthcare disparities.10 These unconscious biases are learned over time through repeated personal experiences and cultural socialization, can be activated unintentionally (often outside one’s own awareness), and are difficult to control.11 Implicit biases affect behavior through a distinct two-step process. First, biases are activated in the presence of a member of a social group and then are applied so that they affect the individual’s behavior related to that group member.12 In the healthcare context, for instance, implicit biases may be activated when a pharmacist is interacting with a specific ethnic minority patient, particularly under conditions that tax her cognitive capacity (e.g., stress, time-pressure, fatigue, etc.), and can then influence how she communicates with and makes decisions about the patient. Research has indicated that these biases affect the quality of patient-clinician interactions, treatment decisions, adherence, and patient health outcomes with the strongest evidence for impact on patient-provider interactions (e.g., less patient-centered communication, warmth, and collaboration).13 Mindful practices can be a promising and potentially sustainable way to address this problem.

Reducing Bias Through Meditation

Mindfulness involves paying attention to the experience in the present moment, emotional regulation, self-awareness and having a nonjudgmental and curious approach toward the experience.14 Therefore, it makes sense that this “mode of awareness” can be enacted in different situations, including those which are emotionally challenging.14 Becoming aware of and being able to regulate one’s stereotypic and prejudicial biases once they are activated is a key element in reducing the impact of implicit biases on behavior.15 In particular, meditation promotes early awareness of emotions, so one is better able to engage in regulation before the emotional responses become intense.16 In a study conducted by Irving et al.,17 participants reported that after completing a Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program their ability to be non-judgmentally aware of their thoughts, sensations and emotions and their ability to regulate their attention and emotions in clinical encounters increased. This encourages the practice of mindful meditation to help clinicians be aware of biases once they are activated and to engage in self-regulatory processes so one can act in a manner more congruent with their values.

It has been shown that implicit biases are more likely to be activated and applied when individuals experience greater cognitive load, defined as the amount of mental activity imposed on working memory.18 An increasing number of studies have found that internal sources of cognitive load (e.g.. burnout, stress, anxiety, depression, decreased empathy, and exhaustion) among clinicians can be reduced through mindful meditation.19 Meditation has also been shown to promote empathy and compassion, which reduces the activation and application of implicit bias and promotes a willingness to engage with members of minority groups.20 In a study by Rosenberg et al.,21 participants who were assigned to three months of intensive meditation training experienced greater sympathetic concern and fewer displays of emotions like anger, contempt, and disgust. Meditation has also been shown to improve patient-centered communication. Clinicians who completed a program focused on mindful communication reported improvements in their ability to listen attentively and be present in their communication with patients.22 This ability to be mindful leads to a decrease in implicit bias by allowing the clinician to focus on a patient’s individual characteristics rather than his or her group membership.22 Using meditation to decrease cognitive load, promote empathy, and improve patient centered communication can lead to decreases in implicit biases and a better quality of patient care.

Advantage of a Mindful Approach

There are certain advantages to using mindful approaches to address implicit bias. Mindful practice is explicitly designed to foster non-judgmental awareness through meditation, wherein individuals learn to accept all feelings that come up in the present moment, with the knowledge that these feelings are “visitors” that come unbidden and will pass. This can help clinicians accept even prejudiced feelings and beliefs, without pushing them away, so they can be examined. Mindfulness meditation promotes early awareness of these emotions and beliefs, so one is better able to engage in regulation before the emotional responses become intense.16 In essence, implicit bias is not a fixed trait that one can do little about but instead the bias is viewed as thoughts and feelings that emerge in consciousness, in varying situations, which can be accessible through close attention to the body and the mind (meditation).

Within the literature, interventions to address implicit bias tend to be single-session, classroom-based, and aimed at increasing the learners’ awareness about the existence of implicit bias through different testing methods.10 A drawback with these types of interventions is that clinicians can discover that implicit bias exists within oneself but not know how to actually address it. In contrast, mindful meditation is expected to reduce implicit bias through the automatic development of awareness, sustained attention, a focus on the present moment, non-judgmental acceptance, enhanced emotional regulation, increased compassion, and reduced stress.23 In this way, using mindful meditation as a sustained skill can become a tool the clinician can utilize and practice to actively reduce implicit bias when it appears to be affecting clinical judgment and patient interactions.

Case Example

The following example illustrates how mindfulness meditation may reduce the effects of implicit bias in patient care. Recall the pharmacy visit from the patient with chronic pain. This time consider the scenario in an overcrowded clinic in which the patient, who is a member of a racial or ethnic minority group, is demanding a narcotic. We have previously stated that it is likely that if the pharmacist or pharmacy technician has a regular mindful meditation practice, they may be less likely to be influenced by increased internal sources of cognitive load, so that implicit biases will be less likely to arise. If implicit biases do arise, this mindful clinician is more likely to become aware of these emotions (perhaps anger, judgment or frustration) arising in her body and the immediate stereotypic beliefs that enter the mind and accept those feelings. This is possible since she has practiced taking a non-judgmental stance in meditation. A common reaction may be, “Why is this patient drug seeking? Why are they so demanding?” At that moment she can pause and take a breath, adjust her own behavior, taking a moment to reconnect with the patient, and perhaps listen more carefully to the patient’s story, or ask about the events surrounding the situation that led to asking for a narcotic prescription. This could reverse the negative course of the situation, ensuring that the automatic stereotype that was activated did not adversely affect the therapeutic relationship and the clinical decision-making process.

IMPROVING PATIENT SAFETY THROUGH MINDFUL PRACTICE

Patient safety has been a topic of considerable interest over the last decade. There has been significant progress in understanding, identifying, and addressing errors at a system level; however, the performance of individual clinicians remains a crucial and largely unaddressed element of patient safety.24 Process knowledge is knowing how to accomplish a task, such as gathering information, performing procedures, and making decisions.25 Process knowledge also includes reflecting on one's own mental processes, in other words thinking about how you think.3 Reduction of medical errors requires an individual’s knowledge of his/her thinking processes in order for that process to be examined and the subsequent steps taken to prevent a medical error. In a favorable clinical environment, mindfulness could be executed with relative ease as the clinician can afford the time and effort to do so. However, interruptions are widespread in a busy and often chaotic practice environment. These interruptions often cause clinicians to make quick, intuitive, and automatic decisions without the benefit of giving purposeful and intentional thought to the rationale behind the decision. A practiced, mindful clinician could deliberately detach themselves from the immediate context of a clinical decision within a busy environment, in order to reflect upon the thinking process in hopes of reducing medical errors.23

Curiosity is not only central to caring about the patient and to solving problems, but it can also lead to reduced medical errors.26 Consider the following clinical scenario that could lead to an unintended medical error. A trainee reported a patient as having had a history of "BKA" (below-the-knee amputation) without noting that the patient, in fact, had both feet. A transcriptionist had mis-transcribed DKA (diabetic ketoacidosis) while charting and the assertion went unchallenged.27 The student's lack of curiosity led to mistaking the chart information for the actual truth instead of investigating the patient. Perhaps a simple glance at the patient would have indeed indicated two intact lower legs. At this point let’s review the characteristics of a mindful practice (refer to Table 1), which stated that active observation of oneself, patient and the problem as well as having curiosity is a necessary characteristic in a mindful clinician. Had the trainee actively looked at the patient, used curiosity and noted the incorrect information in the chart, there would have been no error. While this is an example of an error without major consequences, it gives a clear glimpse of how practicing without being mindful can lead to errors that could be easily avoided. Consider another clinical scenario to highlight how mindfulness can reduce errors.

Case Example

A female comes to your pharmacy asking if you would call her physician for a refill on her benzodiazepine. She tells you she has been anxious at work; occasionally her heart feels like it has been racing; and she is restless all day long. She has not taken the benzodiazepine in the past few months but states her anxiety is now getting worse and she wishes to go back on the medication. You place a call to the physician to fulfill her request and the office states they will call you back.

While the customer is waiting, she mentions offhandedly that she has been coughing and has used her asthma rescue inhaler on most days of the past month. The pharmacist recognizes the persistent asthma symptoms and notes that there is no asthma controller medication on her profile. The pharmacist knows that both the uncontrolled asthma symptoms and agitation from overuse of the rescue inhaler could contribute to her anxiety issues. The pharmacist places a second call to the physician to recommend a maintenance (preventative) inhaler for the patient and cancels the request for the benzodiazepine. At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with the clinical pharmacist, the patient states that her coughing has resolved, and her anxiety has improved. She in fact remained on the maintenance inhaler with very little use of the rescue inhaler and no longer thinks the benzodiazepine is necessary.

The pharmacist used several mindfulness qualities in the encounter (refer to Table 1). The pharmacist used the quality of the beginner's mind, seeing a familiar situation through new eyes. This allowed her to remain open to the potential role of asthma symptoms and medication as contributors to the anxiety issues. Non-attachment to the initial indication of a medication (benzodiazepine) to relieve anxiety issues allowed the pharmacist to incorporate the additional asthma history and reach the correct medication necessary to alleviate the patient’s symptoms. Finally, the pharmacist used peripheral vision by not letting the fact that the patient had used a benzodiazepine in the past for an anxiety disorder cloud her decision-making process. Had this mindful skill not been utilized this would have resulted in an incorrect medication leaving the underlying medical condition untreated.

Clouded by Emotions

Historically, the prevailing view in medicine is that clinical decisions should be objective and free from emotions.28. It was believed that one could not be objective and rational if emotion entered the reasoning process. However, despite what we might believe, our emotions influence almost every decision that we make.28 Many factors may be unconsciously affecting clinical decision making and go unnoticed by a busy clinician. These factors will certainly affect the emotional state of the clinician and influence clinical practice. A mindful clinician would be aware of how these factors are affecting their mood, decision making processes and patient interactions and strive to actively filter them to reduce errors and improve patient safety. Some of these factors are listed in Table 4.

| Table 4. Factors Influencing Clinical Decision Making28 |

| Factors |

Examples |

| Environmental factors |

Disruptions, lack of trained staff, lack of policies/procedures, noisy working environment |

| Patient transference factors |

Labeling patients based on past experiences, biases, prejudices, patient blaming |

| Internal clinician factors |

Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, emotional avoidance, sleep deprivation, stress, burnout |

A mindful practitioner attends, in a nonjudgmental way, to his or her own mental processes during ordinary everyday tasks. In order to improve patient safety, a mindful clinician will need to make conscious their previously unconscious actions and errors and work on ways to minimize how these affect future behaviors.

TOOLS TO MEASURE MINDFULNESS

In order to establish a mindful practice approach, it would seem useful for a clinician to be able to measure their own mindfulness. There have been several instruments validated that measure mindfulness. Below are two such instruments with links for easy access for individual mindful assessments. Please note there are many instruments available to measure mindfulness and the participant is encouraged to investigate other assessments as well.

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) is a 15-item self-report survey that measures the awareness of and attention to what is taking place in the present. Participants indicate whether they frequently or infrequently experience each item using a 6-point Likert scale. The scale was developed with the understanding that people likely have better conscious access to information about their tendency to be mindless rather than mindful. It has been validated with college, community and cancer patient samples. 29 The survey takes 10 minutes or less to complete.

The scale can be accessed at the following website: https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/mindfulnessscale.pdf

Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory

The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) is a valid and reliable questionnaire for measuring mindfulness. The validity of this scale was confirmed through its moderate to strong correlations with measures of self-awareness and self-knowledge. A longer version of the FMI exists in a 30-item scale but was later adapted to a 14-item version currently used in practice and for research purpose. This inventory can be used in subjects without previous meditation experience.30 The survey takes 10 minutes or less to complete.

The scale can be accessed at the following website:

http://www.mindfulness-extended.nl/content3/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Freiburg-Mindfulness-Inventory.pdf

CONCLUSION

The acquisition of medical knowledge, assimilation of clinical information, and continued sharpening of skills are vital to professional competence. Likewise, the continual advancement of interpersonal skills, steady development of increased intrapersonal and interpersonal awareness, and the capacity to attend to patients with presence are central tasks that will enable the clinician to practice high quality, patient-centered care. A desirable outcome of mindful practice is the integration of these skills incorporating them into each patient encounter. However, even the most accomplished practitioners cannot claim to be mindful all the time. Therefore, mindful practice is a process and a goal, not a static state of mind.

The goals of a mindful practice include fostering attentive observation; countering implicit bias; reducing medical errors to improve patient safety; fostering caring, compassion and empathy toward patients; and promoting resilience, health and well-being of the health care professional. At its most basic interpretation, improving mindfulness is about understanding yourself and being “in the moment”. Clinicians have a moral obligation to their patients and themselves to be as aware, present, and observant as possible. With the correct tools and practice of a mindful approach, one can maintain the highest level of not only patient care, but self-care as well.

REFERENCES

- Epstein R. Behavioral Medicine: A Guide for Clinical Practice. Mindful Practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019.

- Novack DH, Suchman AL, Clark W, et al. Calibrating the physician: personal awareness and effective patient care. 1997;278:502-509.

- Epstein RM. Mindful Practice. 1999;282(9):833–839.

- Beach MC, Roter D, Korthuis PT, et al. A multicenter study of physician mindfulness and health care quality. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):421-428.

- Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–1293.

- Smith RC, Zinny G. Physicians’ emotional reactions to patients. Psychosomatics. 1988;29:392-397.

- Smith RC, Osborn GG, Dwamena FC, et al. Essentials of Psychiatry in Primary Care: Behavioral Health in the Medical Setting. Enhancing Your Own Care. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019.

- Goleman D. Working with Emotional Intelligence. New York. NY: Bantam; 2000.

- Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–1293.

- Zestcott CA, Blair IV, Stone J. Examining the presence, consequences and reduction of implicit bias in health care: a narrative review. Group Process Intergr Relat. 2016;19(4):528-542.

- Devine PG, Forscher PS, Austin AJ, et al. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: a prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48(6):1267-1278.

- Stone J. Moskowitz GB. Non-conscious bias in medical decision making: what can be done to reduce it? Med Educ. 2011;45(8):768-776.

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):60-76.

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, et al. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2004;11(3):230-241.

- Dovidio JF, Fiske ST. Under the radar: how unexamined biases in decision making processes in clinical interactions can contribute to health care disparities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):945-952.

- Teper R, Segal ZV, Inzlich M. Inside the mindful mind: how mindfulness enhances emotion regulation through improvements in executive control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(6):449-454.

- Irving JA, Park-Saltzman J, Fitzpatrick, et al. Experiences of health care professionals enrolled in mindfulness-based medical practice: a grounded theory model. Mindfulness. 2014;5(1):60-71.

- Burgess DJ. Are providers more likely to contribute to healthcare disparities under high levels of cognitive load? How features of the healthcare setting may lead to in medical decision making. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(2):246-257.

- Lamothe M, Rondeau E, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, et al. Outcomes of MBSR or MBSR-based interventions in health care providers: a systematic review with a focus on empathy and emotional competencies. Complement Ther Med. 2016; 24:19-28.

- Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV, Richeson JA, et al. Perspective taking combats automatic expressions of racial bias. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100(6):1027.

- Rosenberg EL, Zanesco AP, King BG, et al. Intensive meditation training influences emotional responses to suffering. Emotion. 2015;15(6):775.

- Beckman HB, Wendland M, Mooney C, et al. The impact of a program in mindful communication on primary care physicians. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2012;87(6):815-819.

- Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78:775-80.

- Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors—the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301(10):1060-1062.

- Eraut M. Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. Learning Professional Processes: Public Knowledge and Personal Experience. London, England: Falmer Press; 1994:100-122.

- Peabody F. The care of the patient. 1927;88:877-882.

- Fitzgerald FT. Curiosity. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:70-72.

- Croskerry P, Abbass AA, Wu AW. How doctors feel: affective issues in patients' safety. Lancet. 2008;372(9645):1205-1206.

- Brown, KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Person Soc Psych. 2003;84:822-848.

- Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmuller V, et al. Measuring mindfulness- the freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI). Person Indiv Diff. 2006;40:1543-1555.

Back to Top