Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

The Physical and Psychological Health Consequences of Trafficked Women

INTRODUCTION

A modern-day form of slavery, human trafficking may be thought of as an epidemic that is hidden in plain sight. Human slavery has a long history around the world. Over the centuries, slave traders in the 1700s and 1800s plied the waters between Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean; the history of the United States as well is marred with tragic stories of slavery. Today traffickers still troll inner cities, impoverished areas, and highways, looking for someone to entrap and then sell. Indeed, the for-profit sale of a person as a commodity is not limited to time, geography, ethnicity, economic status or gender. Over the decades, various countries, parliaments, legislative bodies, as well as individuals in the public eye and those working quietly and covertly, have sought to rid the world of this injustice. Nevertheless, the reality of the 21st century is that slavery in the form of human trafficking still exists. Every year millions of men, women, and children around the world, including the United States, may be subject to force, fraud, or coercion for the purposes of sexual exploitation or forced labor.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), on any given day in 2016, 40 million people were victims of modern slavery. Women and girls accounted for 71% of modern slavery victims. In 2016, 4.8 million people were victims of forced sexual exploitation with women and girls accounting for more than 99% of all victims of forced sexual exploitation.1 Trafficking in women is a severe form of gender-based violence and a tragic violation of human rights. Women and adolescents who are trafficked suffer some of the most unspeakable acts of abuse, exploitation and degradation. The damage to their physical health and mental well-being is often profound and enduring.2 This activity will explore the devastating effects trafficking has on its female victims.

DEFINITIONS

Although the term trafficking might suggest transportation, trafficked persons can be born into a state of servitude, placed in an exploitative situation, or have consented initially to a job, only to find that they are forced to work without wages, rights, or decent working conditions. The United Nations defines trafficking as "the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation."3 The term human trafficking is not the same as smuggling where a person is willing to be transported to another location, usually across international borders, and has paid someone to take them there. In human trafficking, a person may be willing initially to be moved and may have paid something in advance however, the deception, fraud, or coercion that evolves within that process is the distinguishing hallmark.1

Human trafficking is categorized as either labor trafficking or sex trafficking. One category of trafficking does not preclude the other whereas some victims who are initially labor trafficked can also be sex trafficked. Victims of labor trafficking may be promised well-paying jobs, yet once in the destination country they find themselves trapped in substandard living and working conditions. In these situations, abuse can range from the imposition of excessive working hours to verbal and physical abuse to sexual harassment and sexual attacks and may extend to forcing the worker into the sex trade industry. For migrant workers, invalid contract terms and unsafe working conditions are setups for abuse. Imposition of the huge debts these workers are required to pay off may be a path of debt payment through sexual favors. Domestic servants in an informal workplace may be physically, socially or culturally isolated allowing their employer to take advantage of them and coercing them to provide sexual services to the employer or his or her guests and family.4

Labor Trafficking

Forced labor is defined by the ILO Forced Labor Convention, as “all work or service that is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”5 A forced labor situation is determined by the nature of the relationship between a person and an “employer” and not by the type of activity performed, however arduous or hazardous the conditions of work may be or whether it is a legal or illegal activity. Regardless of the setting, an identifying feature of situations of forced labor are lack of voluntariness in taking the job or accepting the working conditions, and the application of a penalty or a threat of a penalty to prevent an individual from leaving a situation or otherwise to compel work.1

Sex Trafficking

The United States Government defines sex trafficking as, “a commercial act in which a sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age.”6 Sex trafficking may be a component of sex tourism, gang activity, high-end escort services, or simply as a means to make a profit by exploiting another human being (either male or female). This includes those who have involuntarily entered a form of commercial sexual exploitation, or who have entered the sex industry voluntarily but cannot leave. Information from the International Organization for Migration database suggested that the duration of exploitation was typically protracted; victims were exploited for an average of about two years (23.1 months) before being freed or managing to escape.1 Sex trafficking tends to receive more media coverage because of its sensational nature, but it is not as common as labor trafficking. Of the 4.8 million people forced into sex trafficking in 2016, more than 1 million of the victims were children under the age of 18 years.1 All children found in any type of commercial sexual activity exploitation are considered victims of sexual exploitation. Because child victims of sexual exploitation are particularly difficult to detect, the true figure is likely far higher than the current estimates.

A lesser known type of trafficked victim is the child bride. The ILO estimates that 15.4 million people worldwide are in situations of a forced marriage.7 While forced marriage impacts both sexes, the ILO reports that 84% of the victims are girls and women.7 The ILO estimates that 37% of those living in forced marriage were children at the time of the marriage and 44% of those individuals were under the age of 15 years.7 Forced marriage has negative economic and health impacts and once the marriage is entered into, the risk of additional abuse and exploitation multiplies. Girls are often forced to leave school after marriage leading to limited economic opportunities. Given the age of many brides and their lack of sexual knowledge and experience there can be severe health consequences stemming from early pregnancies before the body is fully developed and adequately able to give birth. In addition, the bride may be forced to work endless hours, provide sexual services to her husband (constituting in some cases rape), physical or verbal abuse, or the threat of being resold if necessary to pay off the husband’s own debt.8

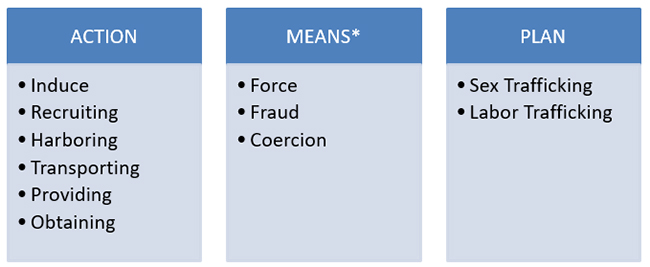

Regardless if the trafficking is sex or labor related there are three elements needed to establish the crime of human trafficking as defined by the Palermo Protocol.9 The three elements required include a trafficker’s action taken through the means of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of exploitation. Understanding it as such leaves little room for interpretation based on the attributes of the victim or the trafficker, such as gender, age, nationality, legal status, or occupation, or on other circumstances surrounding the crime, such as movement or connection to organized crime.10 The Palermo Protocol was established to prevent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children, and is the internationally accepted definition of human trafficking.9 Figure 2 depicts the Action-Means-Purpose (AMP) Model, based on the Palermo Protocol, which is a device used to illustrate and articulate the federal definition of a victim of severe forms of trafficking. At a minimum, one element from each column must be present to establish a potential situation of human trafficking.11

| Figure 2. Action-Means-Purpose (AMP) Model11 |

|

| *Minors induced into commercial sex are human trafficking victims regardless if force, fraud or coercion is present |

RISK FACTORS

The International Program on the Elimination of Child Labor (IPEC) categorizes five kinds of risk factors: individual, family, external and institutional, community and workplace.12 While current stereotypes often depict the victims of human trafficking as innocent, young girls who are seduced or kidnapped from their home countries and forced into the sex industry, it is not just young girls who are trafficked. Men, women, and children of all ages can fall prey to traffickers for purposes of sex and/or labor. Regardless of sex, age, immigration status, or citizenship, certain commonalities exist among victims of trafficking such as their vulnerability and struggles to meet basic life needs. Victims of human trafficking, share other characteristics that place them at risk for being trafficked which include poverty, limited education, lack of work opportunities, lack of family support, history of abuse, health or mental health challenges, and living in vulnerable areas (e.g., areas with police corruption and high crime).13 Refer to Table 1 for more information on the specific items applicable to each category of risk factors.

| Table 1. Risk Factors for Human Trafficking12,13,14 |

| Category |

Factors |

| Individual |

Age

Sex

Being a marginalized ethnic minority with little access to services

No birth registration

Lack of citizenship proof

Orphan/runaway

Lack of education/skills

Low self-esteem

Naivety

Negative peer pressure

School drop out

Family abuse/violence

Dating abuse history

Minimal social support

Attraction to city life versus rural living

|

| Family |

Being from a marginalized ethnic group or subservient caste

Poor single parent family

Poor large family

Death in a poor family

Patriarchal home

Serious illness in family (HIV/AIDS)

Sexual abuse

Alcohol/drug abuse

Family debt

|

| External and Institutional |

Armed conflict

High unemployment rates

Natural disasters

Strict migration controls

Weak legal frameworks/law enforcement corruption

Education not relevant to labor markets

Gender discrimination in education and labor

|

| Community |

Close to a border with a more prosperous country

Long distance to secondary school/training centers

Roads facilitating access to large urban areas

Lack of police, trained railway staff and border guards

Lack of community entertainment

|

| Workplace |

Unsupervised hiring of workers

Poor working conditions

Lack of labor inspection and protection

Inability to change employer

Undercover entertainment (e.g., hairdresser, massage)

Public tolerance of prostitution, begging and sweatshops

|

Physical Violence Prior to Trafficking

Trafficked women often have prior histories of violence, abuse and neglect. Some women have moved from very violent and unsettled circumstances into the trafficking situation. This level of violence may have impacted the woman’s decisions to be influenced into trafficking and/or may have made her an easy target for the trafficker. A women's history of physical and sexual violence also suggests that women surviving a trafficking ordeal are likely to have a complex health profile that represents not only the harm she sustained during the trafficking experience, but the cumulative toll of the abuse before and after she left home. The prevalence and the nature of violence that women experienced in their home countries indicate that a significant portion may encounter dangers to their safety and well-being if they return to the situation from which they departed and may imply questions surrounding a woman’s desire to return to a home that was previously unsafe.2

In a study by Zimmerman et al., women responded to questions about exposure to violence before they were trafficked. The data showed that 60% of the women in the study reported having experienced at least one form of violence (physical or sexual) prior to having been trafficked. Half of the women (50%) said that they had been physically assaulted, while 32% reported a forced or coerced sexual experience prior to being trafficked. Before they were 15 years old, 14% of the women had experienced sexual violence and after age 15, 25% of the women experienced sexual violence. Twenty-two percent of the women reported both physical and sexual violence. The women in this study were also asked about the perpetrators of the violence with a majority of women reporting most perpetrators were family members (Table 2).2

| Table 2. Perpetrators of Physical Violence2 |

| Perpetrator |

Percentage of women* |

| Father |

44% |

| Mother |

31% |

| Other family member |

25% |

| Husband/partner |

13% |

| Boyfriend |

12% |

| Acquaintance |

9% |

| Stranger |

12% |

| Other |

4% |

| *Percentage total adds up to > 100% due to many women reporting more than one perpetrator |

Numerous studies demonstrate that the negative effects of multiple traumas are greater than those of single traumas.15 The abuses preceding the violations women endured during the trafficking period are likely to have taken a cumulative toll on their physical and psychological health. As a result, these women are likely to have a very complex health profile that not only represents the ordeals sustained during the trafficking experience, but the cumulative toll of the abuse before she left home. The high percentage of women who report pre-trafficking violence requires intensive and specialized efforts for prevention and dedicated health-care resources.

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES

To better understand how events during the trafficking situation put a woman's health in jeopardy, it is first necessary to understand the range of experiences women face during the time they were trafficked. Studies have shown that most women will experience physical violence, sexual violence or both. One study indicated that as many as 71% of women in a trafficking situation will experience both forms of abuse.2 These types of abuse may range from homicide and torture, psychological abuse, horrific work and living conditions, to extreme deprivation while in transit.16 Table 4 lists some types of physical abuse reported by women who were trafficked and specific sites of injury as a result of this abuse.

| Table 4. Types of Physical Violence and Injury Sites2 |

| Types of Physical Violence |

Sites of Injury |

| Burned with cigarettes |

Head/Neck |

| Choked |

Genitalia |

| Kicked in the head/back |

Face/Mouth/Nose/Eyes |

| Hair pulled |

Back/Spine |

| Head slammed against floor/walls |

Legs/Feet |

| Assaulted with gun, knife or other object |

Kidneys/Pelvis/Abdomen |

Just as with violence, threats are a hallmark of the trafficking experience. Warnings against escape seem to be among the most frequent type of threats however, murder threats are not uncommon. Women in these situations tend to come from countries where corruption is rampant and law enforcement is untrustworthy, in this case women may have believed they were safer not to turn to law enforcement for assistance in removing themselves from the trafficking situation. Traffickers will often threaten to turn women over to the authorities for not having the proper identification documents or violating immigration and prostitution laws making women even more frightened to leave. By creating this unpredictable and unsafe atmosphere, traffickers can maintain a considerable amount of control by constantly keeping the women on edge.2 Perpetrators of torture are known to employ similar tactics aimed at destabilizing their victims and creating extreme uncertainty about the future.17

Another defining feature of the trafficking experience is the loss of freedom. Few women are free to choose what happens to their bodies, how or when it happens, or by whom. In these situations, women are typically not allowed to decide when or what they eat, when they sleep, or when to use restroom facilities. A traditional arrangement tends to be for women to be locked up or watched during all non-working hours and then escorted to the work-venue or the client. In some unfortunate cases, when not in the sex act, women were forced to do household chores.2 Women’s confinement combined with the threats and violence serve to underline the limited opportunities victims have to escape making their sense of entrapment absolute.

The abuse and control tactics employed by the trafficker are all–encompassing and affect nearly every aspect of a women’s daily life. Women in these situations tend to lose the self-determination to free themselves from their abuser and the feeling of hopelessness and mental defeat will adversely affect a women’s health. Experts on torture suggest that the degree of predictability and the sense of control that an individual has over the event are the two variables that most dramatically effect whether certain stimuli will have deleterious health consequences.17 Dramatic effects on a woman’s physical and psychological health status are easily recognizable given that this form of torture clearly exists in many sex trafficking scenarios.

Physical Health Symptoms

It is not surprising that female victims rated their health poorly, as many of them are likely to be burdened with numerous and concurrent physical health problems. In comparison with a general female population, research on violence and physical health outcomes suggest women who experience abuse are nearly 1.5-3.5 times more likely to perceive their health as poorer than women who have not been abused. 18 In light of women’s health, especially the diversity of the health problems that have been reported, although sexual and reproductive health has frequently been a focus of discussions on health and trafficking, women themselves perceive other physical health symptoms as equally or more problematic.2 Neurological, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and dermatological complaints are all very common among trafficked women. The most prevalent and severe symptoms reported by women in the study by Zimmerman et all were headaches, fatigue, dizzy spells, difficulty remembering and stomach or abdominal pain.2 The symptom patterns detected among trafficked women are consistent with the health outcomes identified in survivors of sexual abuse, rape and intimate partner violence.18 Refer to Table 5 for a more detailed list of physical symptoms.

| Table 5. Physical Health Consequences of Trafficking2 |

| Condition |

Symptoms/Outcomes |

| Neurological complications |

Headaches, blurred vision, vertigo, fainting, post-concussive syndromes, seizure disorders |

| Gastrointestinal complications |

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Dermatological problems |

Lice, scabies, itching, face rashes, acne, sores |

| Cardiovascular complications |

Chest pain, difficulty breathing |

| Musculoskeletal complications |

Back pain, fractures, sprains, joint/muscle pain, tooth pain, facial injuries, dental complications |

| Cognitive problems |

Difficulty remembering, confusion |

| Miscellaneous |

Exhaustion, malnutrition, anemia, weakened immune system, sensory and nerve damage |

Sexual and Reproductive Health Symptoms

The adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes among trafficked women are typically a consequence of sexual violence and the short and long-term consequences of sexual violence are numerous and well documented.19 There are numerous types of sexual abuse that occur ranging from forced vaginal, oral, or anal sex; gang rape; forced degrading sexual acts; forced unprotected sex; coerced misuse of oral contraceptives; or forced sex during pregnancy.2 For those women who have never had sex before, the consequences of forced sex may be significant. Women without prior intercourse experience who have been sexually assaulted are more likely to experience some type of physical genital trauma, although the severity will vary depending on the specific circumstances of the assault.20 Women's strong focus on their sexual and reproductive health reflects their concern not only on current symptoms, but also these women may have significant concerns about infertility.2 Many of the women who are trafficked will still be at a young enough age where they may want children and a family. Even though the possibility of infertility is very real, it is by no means an inevitable conclusion for these women especially if they can be led to the appropriate health resources post-trafficking. Table 6 lists the specific sexual and reproductive health consequences experienced by trafficked women.

| Table 6. Sexual and Reproductive Health Consequences2 |

| Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) |

| Urinary tract infections (UTI) |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) |

| Cystitis |

| Cervical Cancer |

| Infertility |

| Unwanted pregnancy/forced abortion |

| HIV/AIDS |

| Amenorrhea/dysmenorrhea |

| Acute or chronic pain during sex |

| Tearing or other damage to vaginal tract |

Mental Health Symptoms

The physical and psychological control tactics used by traffickers, combined with the physical and sexual abuses leave an enduring imprint on a woman's psychological health and are perhaps among the most painful and difficult health problems to manage. Research is increasingly demonstrating that trauma exposure may precipitate symptoms such as depression, anxiety, hostility and post-traumatic stress disorder all of which are commonly seen in this population (Table 7).21 Since traffickers make women believe that they are in imminent and constant danger, women exist in a heightened state of alert. The normal human reaction triggers integrated physical and psychological responses that prepare the individual to either flee the situation or to defend herself from this danger. When this threat is chronic, individuals find it increasingly difficult to turn off this normal biological response and in turn become unable to adapt or respond appropriately even when the constant threat is removed. 17 The psychological symptoms observed in these women also indicate that women's cognitive functioning may be negatively affected.2 Cognitive impairment has serious implications for women's health, as well as for practical matters such as being able to make sound and safe decisions about everyday life activities once escaping the trafficking situation. The abuses and exploitation perpetrated on women who are trafficked have deleterious mental health effects and their emotional suffering appears to be a lingering and profoundly painful aftermath of the trafficking experience.

| Table 7. Mental Health Consequences2 |

| Suicidal ideation |

| Depression |

| Anxiety |

| Sleep disturbances/frequent nightmares |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) |

| Hostility/irritability/aggression |

| Substance misuse/addiction |

| Eating disorders |

| Identity and self-esteem problems/stigma/shame |

| Difficulty developing and maintaining intimate relationships |

| Obsessive compulsive behaviors/phobias |

| Somatic complaints (e.g., chronic headaches, stomach pain, trembling, heart palpitations) |

IDENTIFICATION AND INITIAL ASSESSMENT OF TRAFFICKED WOMEN

Interviewing a woman who has been trafficked raises several ethical questions and safety concerns for the woman, others close to her, and for the interviewer. Having a sound understanding of the risks, ethical considerations, and the practical realities related to trafficking can help minimize the dangers and increase the likelihood that a woman will disclose relevant and accurate information. There are several factors that serve as barriers to disclosing trafficking to health care providers. Physical threats against the victim themselves or other family members, lack of control over their identification documents, or other means of manipulation by the trafficker may all serve as barriers to communication with the health care provider.22 As a result, healthcare providers must have a low threshold of suspicion for indicators of human trafficking. Some signs that may raise suspicion are included in Table 8.

| Table 8. Red Flags Consistent with Human Trafficking22,23 |

| Someone else is speaking for the patient or takes control of the visit |

| Patient is unaware of his/her location, current date or time |

| Someone else insists on serving as the interpreter for the patient |

| Patient exhibits fear, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, submission or tension |

| Signs of physical or sexual abuse |

| Signs of medical neglect or torture |

| Patient is reluctant to explain the injury or trauma |

| Patient does not make eye contact |

| Patient has no financial means |

| Patient has no identification documents |

Interviewing the victim should follow the guidelines for any suspected abuse; a safe and strictly confidential discussion must be assured with informed consent at each step. Questions should only be asked when the victim is alone so as to not raise suspicion when the trafficker is present resulting in possible increased harm to the victim. If approached in a sensitive and non-judgmental manner and the greater the extent to which a victim feels respected and that their welfare is a priority, the more likely they are to share accurate and intimate details of the experience. There are ten guiding principles to the ethical and safe conduct of interviews that a health care professional can follow. These are adopted from the World Health Organization’s Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Interviewing Trafficked Women (Table 9).24

| Table 9. Ten Guiding Principles to Safe and Ethical Interviewing24 |

| Principle |

Detail |

| Do no harm |

Treat each situation as if there is extreme danger to the victim until proven otherwise. Do not undertake any interview that will make the situation worse |

| Assess the risks |

Learn about the risks associated with trafficking |

| Be ready to provide accurate referral information |

Be prepared with legal, health, shelter, social support and security services |

| Adequately select your staff who will assist |

Develop adequate methods for screening and training all team members |

| Ensure anonymity and confidentiality |

Protect identity and confidentiality through the entire process including up to the time the information is made public knowledge |

| Get informed consent |

The victim has a right to know the purpose of the interview, the right to not answer questions, the right to terminate the interview, the right to put restrictions on how the information is used |

| Respect each individual situation |

Each victim has different concerns and priorities and deserves respect regardless of others assessment of the situation |

| Be prepared to respond in an emergency |

Have emergency contingency plans in cases of imminent danger |

| Put information to good use |

Use the information to help the individual and move forward in developing policies or procedures that help all victims |

When patients exhibit signs or symptoms that are concerning for trafficking, or any of the red flags discussed in Table 8 are present, a number of additional questions can be asked to elicit further history concerning trafficking.22,23,24 The first three questions will allow you to assess security and determine the safety of conducting the interview. Some questions to consider are as follows:

- "Do you have any concerns about carrying out this interview with me?"

- "Do you think that talking to me could pose any problems for you, for example, with those who trafficked you, your family, friends, or anyone who is assisting you?"

- "Do you feel this is a good time and place to discuss your experience? If not, is there a better time and place?"

- “Is someone holding your passport or identification documents?”

- “Has anyone threatened to hurt you or your family if you leave?”

- “Has anyone physically or sexually abused you?”

- “Does anyone take all or part of the money you earn?”

- “When not working, can you come and go as you please?”

- "Have you ever been forced to work to pay off debt?"

- "Has anyone lied to you about the type of work you would be doing?"

- “What are your living and working conditions like?”

Each phase of the interview process can pose risks to a respondent. These should be recognized, assessed and appropriate security measures should be undertaken. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends four stages to the interview process.24 The four stages are discussed below.

Stage One: Making the initial contact. If the victim might still be in imminent danger, consider a secure means of communication through a local organization known to the victim and that she trusts, such as social service groups, shelters or refuges.

Stage Two: Identify time and place. Interviews must be in a completely private setting where random interruptions will not occur making the respondent ill at ease. Before and throughout the interview, the woman should be free to reschedule or relocate the interview to a time or place that may be safer or more convenient for her.

Stage Three: Conducting the interview. Come prepared with questions but keep in mind interviews that yield the most accurate information are those that are unstructured and responsive. This depends on keeping an open mind while demonstrating active listening and empathy. Pity or sympathy may be unwelcomed as many women do not wish to be treated as victims. Watch for clues that indicate that the respondent no longer feels at ease or wishes to terminate the discussion. Consider having a short diversionary questionnaire on another subject (e.g. health topics or cultural practices) that can be utilized if discomfort is noted at any time during the interview.

Stage four: Closing the interview. If possible, interviews should end in a positive manner. The interviewer may use specific examples from her narrative to remind the woman of how well she coped in such difficult circumstances and how helpful she has been with providing information that can be used to help others. Referral information and resources should be offered at this point.

RESOURCES AND REFERRALS

Any patient who discloses a history concerning for either labor or sex trafficking can be referred to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) at 1-888-373-7888. The national 24-hour toll-free hotline, in addition to providing resources directly to individuals experiencing trafficking, can assist health care providers in assessing the level of danger to the patient, provide additional questions to ask, and suggest resources. If there is perceived danger and the patient wants immediate help, NHTRC can assist the provider with the next steps including involving law enforcement for victim safety. There are numerous ways to communicate with NHTRC including text, chat, and on-line. A health care provider can submit a tip online though an anonymous reporting form. If the situation is urgent or has occurred within the last 24 hours, the health care provider is encouraged to call, text or chat with NHTRC. To report a suspicion of trafficking on-line or obtain additional resources the health care provider is directed to the following site: www.traffickingresourcecenter.org.

Even if the patient answers no to the interview questions and trafficking is not a concern there still may be a reason for referral to local services. Health care providers should familiarize themselves with location-specific resources, such as social workers, specialty clinics to care for patients experiencing abuse, and local organizations who provide patients with additional social services. Law enforcement or social service providers should not be contacted without the victim's consent, though laws vary by state and familiarity with the laws in one's own setting will guide behavior. For minors, health care providers must be aware of and follow mandatory reporting requirements for child abuse. A major limitation and reality is that the health care provider may have only one opportunity to see a victim of trafficking. It is useful to have contact information for referral services written on a small card that a woman may take with her after the interview and keep hidden for future reference if and when she decides she needs it. Information should be in the woman's own language and in the local language, if different, so she may get assistance contacting the services. It is imminent that the clinician be prepared with all the necessary multidisciplinary resources to assist the victims at this critical junction.

CONCLUSION

After a trafficking experience, women must grapple with a wide range of emotions, memories of the past, and apprehension about the future. Women must often deal with these issues alongside a variety of physical and emotional health consequences. Post-trafficking victims may be attempting to adjust to a new setting, or they are trying to reintegrate into a once familiar home, regardless their turbulent inner world is set amidst an environment that is often stress-filled and alienating. Assistance cannot be prescriptive, and support should be based on professional assessments of the victim's individual needs, including their experiences of past violence and their prospects for safety and well-being in the future. Community pharmacy personnel in particular are likely to see these patients on a continual basis, and can serve as valuable resources to ensure on-going continual support to victims of trafficking.

References

- Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage. International Labour Office (ILO), Geneva, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2020, from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_575479.pdf.

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. Stolen Smiles: The Physical and Psychological Health Consequences of Women and Adolescents Trafficked to Europe. Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291985739_Stolen_Smiles_The_physical_and_psychological_health_consequences_of_women_and_adolescents_trafficked_in_Europe.

- UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, summary Web page. Retrieved October 16, 2020 from http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/CTOC/index.html.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services. Human Trafficking into and Within the United States: A Review of the Literature. Who Are the Victims of Human Trafficking? (2009). Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/human-trafficking-and-within-united-states-review-literature/who-are-victims-human-trafficking.

- International Labour Organization, Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29). Retrieved October 19, 2020 from https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C029.

- National Institute of Justice. Overview of Human Trafficking and NIJ’s Role. Retrieved October 16, 2020, from https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/overview-human-trafficking-and-nijs-role#note1.

- The Human Trafficking Search. Forced Marriage: A Form of Modern-Day Slavery. Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://humantraffickingsearch.org/forced_marriage/.

- Girls Not Brides. What is the Impact of Childhood Marriage? Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/what-is-the-impact/.

- The Palermo Protocol. Retrieved October 16, 2020 from http://www.kirkleessafeguardingchildren.co.uk/managed/File/Info%20for%20Professionals/2016-01-27%20-%20The%20Palermo%20Protocol%20-%20Definition%20of%20Trafficking.pdf.

- US Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report/.

- National Human Trafficking Resource Center. AMP Model. Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://traffickingresourcecenter.org/sites/default/files/AMP%20Model.pdf.

- Global Estimates of Child Labor: Results and Trends, 2012-2016. International Labour Office (ILO), Geneva, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_575499.pdf.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2009). Human Trafficking into and Within the United States: A Review of the Literature.Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/human-trafficking-and-within-united-states-review-literature.

- National Center on Safe and Supportive Learning Environments. Human Trafficking in America’s Schools: Risk Factors and Indicators. Retrieved October 16, 2020 from https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/human-trafficking-americas-schools/risk-factors-and-indicators.

- Green, B.L., Goodman, L.A., Krupnick, J.L., et al. Outcomes of single versus multiple trauma exposure in a screening sample. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13(2):271-86.

- American Psychological Association. Facts about Trafficking of Women and Girls. Retrieved October 18, 2020 from https://www.apa.org/advocacy/interpersonal-violence/trafficking-women-girls.

- Basolgu M. Torture and its Consequences: Current Treatment Approaches. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1992.

- Coker A, Smith P, Bethea L, et al. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):451-57.

- Mullen P, Romans-Clarkson S, Walton V, and Herbison G. Impact of sexual and physical abuse on women's mental health. Lancet. 1988;1(8590):841-45.

- Biggs M, Stermac L, Divinsky M. Genital injuries following sexual assault of women with and without prior sexual intercourse experience. 1998; 159(1):33-37.

- Wenzel T, Griengl H, Stompe T, et al. Psychological disorders in survivors of torture: exhaustion, impairment and depression. Psychopathology. 2000;33(6):292-96.

- Dolan B, Walsh J. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. Human Trafficking. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY:2021.

- National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC). Framework for a Human Trafficking Protocol in Healthcare Settings 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2020 from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sites/default/files/Framework%20for%20a%20Human%20Trafficking%20Protocol%20in%20Healthcare%20Settings.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Interviewing Trafficked Women. Geneva: WHO, 2003. Retrieved October 19, 2020 from https://www.who.int/mip/2003/other_documents/en/Ethical_Safety-GWH.pdf.

Back to Top