Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Legal and Safety Aspects of Pharmacists as Prescribers

INTRODUCTION

Currently, nearly all states allow pharmacist to prescribe in some fashion. The authority to prescribe exists along a continuum where the authority is either dependent (delegated through a collaborative practice agreement) or independent (authority comes directly from the state, no delegation required). Most states allow for more than one type of prescribing, some collaborative, and some independent prescribing; however, the majority of independent prescribing is medication, or medication category specific and generally addresses a public health issue (e.g., naloxone or opioid antagonists, epinephrine auto-injectors, hormonal contraceptives).1

There are various political and legal aspects to explore in relation to the prescriptive authority of pharmacists. There is a need for pharmacist to assume this role as the focus on safe and effective medication use and the elimination of medication errors continues to increase. In current practice, pharmacist consultation has already evolved into prescribing to ensure safe and effective medication use. As the need for dispensing functions decrease, new roles will need to be assumed and the change in pharmacy curriculum to transition to a Doctor of Pharmacy program has put pharmacists in an ample position to take on new responsibilities as their clinical knowledge and training has increased. Nurse practitioners and physicians' assistants, whose training in clinical pharmacology is conducted by pharmacists, have authority to prescribe in many states and a natural next step would be to enable pharmacist to act as prescribers. Physicians have traditionally been a strong opponent to pharmacists as prescribers in beliefs that it would lead to fragmented care and more medication errors. These opponents state that pharmacists are not trained in diagnosis and question if all pharmacists are competent to prescribe. A pharmacists’ access to patient information is not adequate at this point for competent prescribing in all settings. Despite these arguments proponents state that pharmacist prescribing in pilot studies has been safe, effective, and either equal or superior to physician prescribing.2

There are obviously many unanswered questions that need to be explored in relation to the prescriptive rights of pharmacists. At a minimum, pharmacists must have access to all necessary medical information, obtain adequate training, and understand the legal complexities related to prescribing. Regardless, if all states reach a similar level of pharmacist autonomy in prescribing the landscape of pharmacy practice, particularly in the community and ambulatory settings, will look different than it does today. This manuscript will provide ways to ensure safe and effective prescribing practices as well as identify factors to limit liability concerns related to legal and insurance requirements.

PHARMACISTS AS PRESCRIBERS

The momentum to enable pharmacists to act as prescribers has been building since 1979 when Washington state passed the nation’s first collaborative practice authority for pharmacists. Currently, most states and the District of Columbia enable pharmacist prescriptive authority under Collaborative Practice Agreements (CPAs), standing orders, or statewide protocols.1 The American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) has put forth a definition of prescribing which is no longer merely the act of writing medication instructions. The process of prescribing is more appropriately described by a broad set of activities that include selecting, initiating, monitoring, continuing, modifying, and administering drug therapy.3 To most people the initiating step captures the true essence of prescribing. Each state governments set mandates to determine which health professionals can initiate medications. Full prescriptive authority is granted to physicians within the scope of their practice. Prescriptive authority for non-physicians is typically more variable. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants have gained broader prescriptive authority, but variation still exists in the extent to which medications can be prescribed and to the degree of independence under which this authority may be exercised. Some states allow very narrow prescriptive authority to chiropractors, midwives and naturopaths and some states still prevent this activity outright.1 Pharmacists must be aware of the differing legal requirements and allowable scope of practice within their respective states.

Pharmacist prescriptive authority falls under two broad categories: collaborative prescribing and autonomous prescribing. The hallmark of collaborative prescribing is a collaborative practice agreement (CPA). Collaborative practice agreements create formal relationships between pharmacists and a prescriber that allow for expanded services that a pharmacist can autonomously provide under specified conditions. The prescriber traditionally maintains oversight of the services provided through some mechanism, such as auditing patient records to ensure protocols are being followed. In contrast, autonomous prescribing does not require a CPA between a pharmacist and a prescriber. Even though this type of practice is not centered around a legal written requirement, the pharmacist is still expected to perform collaborative care with the entire health care team.1 There are distinct categories that fall within both collaborative and autonomous prescribing and represent a continuum of autonomy. Each of the different categories is described in Table 1 and represented from most restrictive to least restrictive.

| Table 1. Categories of Collaborative Prescribing and Autonomous Prescribing1 |

| Prescribing Category |

Specific Practice |

Definition |

| Collaborative |

Patient-specific collaborative practice |

A relationship exists between the participating patient, provider and pharmacist. Services are limited to specific patients and typically used for chronic disease management |

| Collaborative |

Population-specific collaborative practice |

An agreement between the provider and the pharmacist that allows services to be provided for broad patient populations regardless if the patient is under the care of collaborating providers. Typically used for acute care and chronic disease management |

| Autonomous |

Statewide protocol |

A protocol published by a state body that is the same for all qualified pharmacists allowing a pharmacist to prescribe medications that are used for preventive care or for acute or self-limiting conditions |

| Autonomous |

Unrestricted category-specific authority |

Pharmacist prescribes without the supervision of a collaborating provider, for legitimate medical purposes and within the scope of usual practice |

Collaborative Prescribing

There are many benefits to collaborative prescribing as both patient-specific CPAs and population-specific CPAs may be used to improve care in chronic disease management. The literature is filled with positive outcomes of how collaborative care with a pharmacist has achieved better outcomes for patients with diabetes, hypertension, and coagulation disorders along with various others. In addition, population-based CPAs have allowed for pharmacists to increase vaccination rates leading to increased preventative care and improved public health.4 A systematic review on the effects of pharmacist prescribing on patient outcomes in the hospital was performed in 2017. Patients were shown to have improved cholesterol levels, blood sugar levels, and improved adherence to warfarin dosing monograms versus physicians. This review also showed that pharmacists made less prescribing errors versus physicians upon admission or in the preoperative setting.15 Population based CPAs can also give access to care that otherwise would not be available to those without access to a physician which is especially valuable in the underserved population.1 We now have evidence that shows improved patient outcomes and improvement in public health that further validates the need for a pharmacist to be involved in the prescribing stages of medication use.

Autonomous Prescribing

Autonomous prescribing while less restrictive does not mean uncoordinated care. Instead it looks more analogous to the interprofessional collaboration which occurs naturally between other health care providers. A statewide protocol is closely related to a population-specific CPA, instead of a physician however parameters are entered into with a representative of the state, usually a Board of Pharmacy or the Department of Health. The benefits to this type of agreement include the ability of the pharmacist to implement a service faster instead of waiting to establish a CPA and it allows for consistency of services across the state. Usually these protocols focus on public health problems or medications which do not require a diagnosis such as hormonal contraception, smoking cessation, naloxone use, tuberculosis skin testing or travel medications. The trade-off for statewide protocols versus CPAs is that these protocols are usually very narrow in their scope and CPAs can allow for a much broader type of practice. Unrestricted category-specific authority is very similar to the scope of statewide protocols but in contrast there is no state derived protocol a pharmacist must follow. Instead, states place general parameters around a specified authority, for example referring to current practice guidelines to guide prescribing. As the guidelines are updated, so too is the pharmacist authority. Such authority for pharmacist prescribing is currently being applied to immunizations, epinephrine autoinjectors, fluoride supplements, and naoloxone.1

Ideally a state model for the purposes of advancing public health and patient care would be a combination of population-specific CPAs, statewide protocols, and unrestricted product-specific prescribing. Some states will allow for a multiple pathways approach where autonomous prescribing strategies are a supplement to, not a replacement for, collaborative prescribing strategies.1 Pharmacists may have the opportunity to choose which type of agreement to enter into and are encouraged to actively investigate the types of authority granted in their respective states.

STEPS FOR EFFECTIVE PRESCRIBING

Like any other process in health care, prescribing should be based on a series of rational steps. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests an ordered approach to prescribing usually taught to physicians or other providers but can be adapted and utilized by the pharmacist. This step wise approach to prescribing suggests that the prescriber should evaluate and define the patient's problem; specify the therapeutic objective; select the appropriate drug therapy; initiate therapy with the appropriate dosing regimen; provide patient education and finally evaluate therapy regularly.5 A pharmacist is also in a key position to recommend non-pharmacological therapy as well such as lifestyle modification or over-the-counter (OTC) products. The following will discuss each step in detail and have been modified to accommodate the pharmacists’ knowledge base and tasks.

Evaluate and define the problem

Prescriptions based merely on a desire to satisfy the patient’s need for some type of therapy are often unsatisfactory and may result in adverse effects. Identifying a specific problem, even if it is tentative, is required. The problem and the reasoning underlying it should be clear and should be shared with the patient.

Consider the pathophysiologic implications

If the disorder is well understood, the pharmacist is in a much better position to offer effective therapy. For example, understanding the pathophysiology involved in suppressing ovulation is helpful in choosing the appropriate birth control method. The patient should be provided with the appropriate level and amount of information about the pathophysiology as well. This may be especially important when adherence is critical to achieve the maximum effectiveness of the medication.

Select a specific therapeutic objective

A therapeutic objective should be chosen for each of the pathophysiologic processes defined in the preceding step. In a patient seeking oral contraceptives, suppressing ovulation to prevent pregnancy is one of the major therapeutic goals that identify the drug groups that should be considered. Preventing the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) through other methods might lead to consideration of additional over-the-counter recommendations.

Select a drug of choice

One or more drug groups will be suggested by each of the therapeutic goals specified in the preceding step. Selection of a drug of choice from among these groups follows from a consideration of the specific characteristics of the patient and the clinical presentation. For certain drugs, patient characteristics such as age, co-occurring diseases, and other medications (prescription and OTC) are extremely important in determining the most suitable drug for management of the present complaint. Next consider any contraindications or potential drug interactions with the selected choice of drug treatment. The WHO suggests that physicians develop a personal formulary which contain drugs that are effective, inexpensive, and well-tolerated that the prescriber can regularly use to treat common problems.6 This may be a helpful tool for the pharmacist as well. More detail will be given in the next section when considering other factors that influence medication selection.

Determine the appropriate dosing regimen

This includes being specific about the amount of medication to be given and the time between doses or the time when the doses are to be given. There are specific questions to consider when determining the appropriate dosing regimen.6

- Is the dosage form suitable for the patient?

- Is the dosage schedule suitable for the patient?

- Is the duration of treatment suitable?

Devise a monitoring plan

Monitoring the treatment enables one to determine whether the chosen drug therapy has been successful or whether additional action is needed. There are two types of monitoring plans discussed in the literature. Passive monitoring means explaining to the patient what to do if the treatment is ineffective, inconvenient or if too many adverse effects occur. In this case monitoring is done by the patient and the prescriber is contacted only if the patient has an issue with the drug therapy. Active monitoring means an appointment is made by the prescriber to determine whether the treatment has been effective. In this situation, the prescriber will need to determine a monitoring interval, which depends on the type of illness, the duration of treatment, and the maximum quantity of drugs to prescribe before requiring a return visit. At the start of treatment, the interval is usually short, but it may gradually become longer, if needed.6 If a pharmacist is prescribing, a passive monitoring approach may be more desirable when recommending OTC products or perhaps even oral contraceptives. In the case of managing chronic disease states, active monitoring is the more acceptable approach.

Regardless of the selected monitoring approach the pharmacist should be able to describe to the patient drug affects that will be monitored and in what way, including laboratory tests if necessary and signs and symptoms that the patient should report. For example, if the pharmacist is involved in a CPA to monitor diabetes, the patient would need to know what outcomes were being monitored (blood sugar, HgA1C) and how they were going to be monitored (blood sugar by glucose meter and HgA1C through laboratory monitoring). A pharmacist should also tell the patient to monitor and report signs and symptoms of hypo or hyperglycemia. The duration of therapy should be made clear so that the patient does not stop taking the drug prematurely and understands why the prescription probably will not be renewed, such as in the case of an antibiotic. For the patient with a chronic condition, the need for prolonged and sometimes indefinite therapy should be explained. If active monitoring is chosen, a clear plan for follow-up should be outlined for the patient including when they should return for evaluation.

Plan a program of patient education

The pharmacist should be prepared to repeat, extend, and reinforce the information transmitted to the patient as often as necessary. The more toxic the drug prescribed, or the more critical adherence is to the intended outcome, the greater the importance of this educational program. Some activities a pharmacist may consider include recurrent and personalized telephone counseling sessions to reinforce the monitoring plan or other important educational objectives, refill reminder phone calls, or motivational interviewing sessions.

FACTORS INFLUENCING MEDICATION SELECTION

The appropriate steps for effective prescribing have been discussed, but it is important to consider some additional criteria when selecting the appropriate medication. Before any medication is prescribed, the prescriber must consider the efficacy, safety and cost of the medication in that order of importance. In the following section efficacy, safety, cost and patient preference will be discussed as factors that influence medication selection.

Efficacy

Without proven efficacy, no medication should be given and the risk versus benefits need to clearly be weighed in the selection process. The quality of medical studies supporting the use of medications varies widely. The strength of any recommendation depends on the trade-off between benefits and risks or burdens and the quality of the evidence regarding treatment effect. The international GRADE group has suggested a grading scheme that classifies recommendations as strong (Grade 1) or weak (Grade 2), according to the balance between benefits, risks, burden, and cost, and the degree of confidence in the estimates of benefits, risks, and burden. The system classifies quality of evidence as high (Grade A), moderate (Grade B), or low (Grade C) according to factors that include the risk of bias, precision of estimates, the consistency of the results, and the directness of the evidence.7 Table 2 will help to explain this grading system so the pharmacist can better understand how to apply it to their practice.

| Table 2. Grading System7 |

|

Grade of Recommendation

|

Benefits versus Risks or Burdens

|

Implications

|

|

Strong recommendation; high quality evidence (1A)

|

Benefits clearly outweigh risks and burdens or vice-versa

|

Recommendation can apply to most patients in certain circumstances. Further research is very unlikely to change confidence in the estimate of effect

|

|

Strong recommendation; moderate quality evidence (1B)

|

Benefits clearly outweigh risks and burdens or vice-versa

|

Recommendation can apply to most patients in certain circumstances. Higher quality research may have an important impact on the estimate of effect and may change the estimate

|

|

Strong recommendation; low or very low-quality evidence (1C)

|

Benefits appear to outweigh risks and burdens or vice-versa

|

Recommendation can apply to most patients in certain circumstances. Higher quality research is likely to have an important impact on the estimate of effect and may change the estimate

|

|

Weak recommendation; high quality evidence (2A)

|

Benefits closely balanced with risks and burdens

|

Best action may differ depending on circumstances, patient or societal values. Further research is very unlikely to change the estimate of effect

|

|

Weak recommendation; moderate quality evidence (2B)

|

Benefits closely balanced with risks and burdens; some uncertainty in the estimate

|

Best action may differ depending on circumstances, patient or societal values. Higher quality research may have an important impact on the estimate of effect and may change the estimate

|

|

Weak recommendation; low or very-low quality evidence (2C)

|

Uncertainty in the estimates of benefits, risks and burdens

|

Other alternatives may be equally reasonable. Higher quality research is likely to have an important impact on the estimate of effect and may change the estimate

|

Among the difficult issues with interpreting clinical trials is whether they can be extrapolated for all drugs in the same class. In general, extrapolation across a class is somewhat hazardous, as drug formulation, absorption, duration of effect, and sometimes drug interactions differ among drugs in the same class. For instance, consider HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, whose effects on LDL cholesterol are mostly affected by drug potency and can often be equated through adjustment of dose, the efficacy related to clinical outcomes and adverse effects may vary. Be wary when applying clinical trial results across the entire class of drugs.

Another issue regarding assessing the validity of clinical trials is the use of surrogate markers in place of hard clinical end points. A clinical trial’s endpoints measure the outcomes the investigators want to study. These clinical outcomes are used to measure the benefit or likely benefit of a therapy and determine whether that benefits outweigh the risks of the drug therapy. Alternatively, investigators may choose an endpoint that is a substitute, or “surrogate”, for the outcome they want to study, and these may be used instead of clinical outcomes in some clinical trials. Surrogate endpoints are used when the clinical outcomes take a very long time to study, or in cases where the clinical benefit of improving the surrogate endpoint, such as controlling blood sugar, is well understood. Some surrogate markers have been demonstrated through rigorous clinical studies to be closely associated with hard clinical end points, providing assurance that they may be trusted as substitutes. Other surrogate markers have less data to justify their use as substitutes. To better understand the difference, consider that many clinical trials, using a range of different blood pressure lowering medications, have demonstrated that reducing systolic blood pressure reduced the risk of stroke. Hence, measurement of reduction in the surrogate endpoint of systolic blood pressure can stand in for the clinical outcome of stroke. Surrogate endpoints should not be confused with clinical outcome assessments and a pharmacist needs to be aware of how to interpret different trails endpoints keeping in mind the critical difference is that clinical outcomes measure a parameter that describes quality and quantity of life.8 For example, a clinical trial that measures a reduction in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RNA levels as a surrogate for medication efficacy instead of extended survival in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) would have very different implications. One could not determine the impact on the quality or quantity of life based on this surrogate endpoint.

The factors above related to assessing efficacy of medications relate to how prescribers evaluate and utilize randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for making clinical decisions. The application of results from an RCT to a specific patient ideally depends on assuring that the patient is like those described as subjects in the study and that the intervention being tested will be provided in the same way as described in the trial. This requires a careful evaluation of the methods section in the manuscript to determine if your patient and your own treatment regimen fits in with the trail intervention. Don’t be the clinician who only reads the abstract, discussion, or conclusion sections to get the “gist” of the trial.

Safety

Throughout all phases of drug development safety is assessed, but at best these trials involve only a few thousand study subjects for most drugs. The complete adverse event profile of a drug is not entirely known at the time of approval because of the small sample size, short duration, and limited generalizability of pre-approval clinical trials. Rarer (and sometimes more serious) side effects may be recognized with much more extensive use, involving tens of thousands of people and this explains why post market studies are required by the FDA. The FDA uses these post market requirements and commitment studies to gather additional information about a product's safety, efficacy, or optimal use.9 MedWatch is the FDAs Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program and acts as a post marketing surveillance system to which clinicians submit reports of adverse drug events encountered while treating their patients. This is an extremely valuable mechanism by which hazards with drugs that were not observed or recognized at the time of approval are identified. The experience with drugs such as troglitazone which was associated with hepatotoxicity emphasizes the importance of post marketing reporting of toxicities associated with newly approved medications. Prescribers may submit reports on any suspected adverse drug (or medical device) effect using a form obtainable from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch/index.cfm.

Cost

The cost of medical care is staggering, partly fueled by the cost of medications. In 2016, the U.S. spent $3,337 billion on national health expenditures, of which $329 billion was spent on prescription drugs.10 In some years, prescription drug spending growth has far exceeded the growth in other medical spending, while in others years it has fallen below that spending. Over the next decade, however, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projects that spending for retail prescription drugs will be the fastest growth health category and will consistently outpace that of other health spending.11 The high cost of prescriptions affects patients as individuals, who sometimes find that they are unable to afford their medications, and as a result these patients often go without drug therapy. This adherence issue increases during difficult economic periods or when people have fixed incomes and must choose between paying for these medications or for their food or mortgage. Consider the effects as hospitals and health systems are forced to pay more for medications causing an increase in other fees to offset this increased expenditure. All these factors increase health care expenditure in society.

Cost effectiveness is another avenue to explore when considering medical interventions and their financial benefit. Compare the cost of aspirin which is far less than the cost of caring for the number of heart attacks and strokes it prevents. In other cases, the cost benefit may be indirect. For example, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, are reported to cause a temporary delay in cognitive decline in patients with dementia.12 If this delay in cognitive decline can prevent a patient from requiring institutionalization or full-time care at home for a period of months or years, the cost of the medication which is much less than the cost of such care becomes cost effective. A pharmacist must consider if the cost of the medication will lead to potential cost savings in the future and have discussions with the patient to help them determine if a medication may be cost-effective.

Patient Preference

With rare exception, prescribers have several possible medications for managing diseases. In all cases, the patient’s inclination to accept the proposed therapy should be considered and the choice of initiating medication treatment or not should be weighed. It is always an option not to offer treatment, and sometimes no treatment is the best option. For example, in a patient who is experiencing a symptom of no clinical consequence, the symptom creates no risk, and almost always resolves without intervention, introducing a medication with risks of adverse effects or other possible complications offers no clinical benefit. In this case, no treatment is an acceptable approach. Patients with potentially life-threatening conditions such as cancer are often treated with potent medications with the potential of adverse effects that are not only intolerable but potentially toxic. When treatments are similar in efficacy but differ in types of toxicities, the patients’ preferences are important. Considering the oncology patient, weighing the patient’s preference to experience hair loss, neuropathy, infertility, or other potential complications should be considered when choosing a chemotherapeutic regimen. Tailoring the medications used in such cases preserves the patient’s autonomy and properly respects his or her right to choose among reasonable options.

CIVIL LAW AND LIABILITY CONCERNS

Indeed, there is a degree of risk inherent in performing many common tasks in almost any pharmacy. The changing health care environment requires pharmacists to critically examine risks in all aspects of their practice, especially as they look to take on more patient-oriented roles such as prescribing. Pharmacists must be aware of the inherent and evolving risks of prescribing and develop strategies to deal with the risks.

When a pharmacist or pharmacy organization is sued, the issue of negligence becomes the key to what the outcome of the lawsuit will be. Negligence theory revolves around either the failure to do something that a reasonable and prudent person would do or doing something that a reasonable and prudent person would not do. There is a specific formula for providing evidence that negligence has occurred. All four elements must be proven to support a cause of action in negligence.13

- A duty must exist: The defendant (pharmacist) developed a relationship with the plaintiff (patient) whereby the defendant owed a duty of due care toward that plaintiff. As an example, when a pharmacist enters a patient-specific CPA, the pharmacist owes that patient a duty of due care in ensuring that the proper medication will be prescribed.

- A breach of duty of due care: The defendant acted in a manner that breached the due care owed to the plaintiff. In the case of a pharmacist prescribing a medication, after assuming the duty, the pharmacist may breach his/her duty by prescribing the wrong medication.

- Causation of harm or injury: The defendant’s breach of duty was either the actual or the proximate cause of the plaintiff’s injury. If a pharmacist prescribed incorrectly, and the patient was injured as the result of the error, the mistake made by the pharmacist may be considered as the actual or proximate cause of that injury.

- Harm or injury did occur: If there is no harm or injury caused as a result of the breach of duty, a claim or cause of action in negligence will fail. Just because the patient received the wrong medication due to inappropriate prescribing, if the patient did not take any of the medication, a claim of negligence would fail since no injury could be accounted for as a result of the breach of duty.

Risk Management Strategies

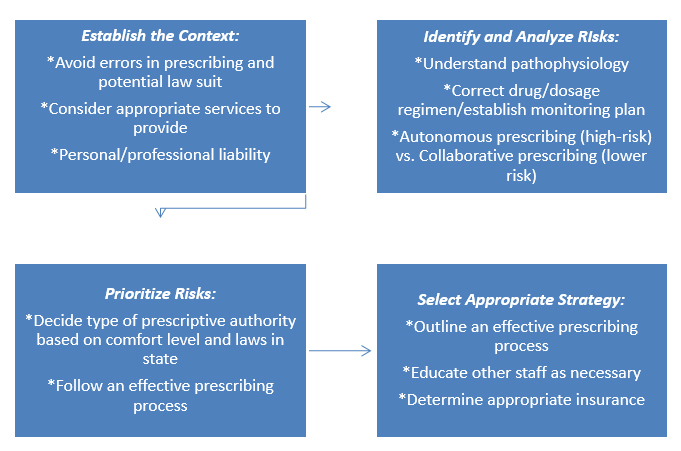

The thought of being sued for something one has done while practicing is not at all pleasant. The first thing that comes to mind is how to prevent this from happening. This question opens the door to a field called risk management that deals with how to reduce and manage exposure to risk. In relation to prescribing, having a sound process for effective prescribing and consistent adherence to the law are essential to minimize exposure to risk. There are certain steps a pharmacist can follow to develop a risk management process and each step is discussed below.14 Figure 1 displays an example of a risk management process used when a pharmacist is deciding whether to enter the prescribing process.

- Establish the context: What are the goals of the risk management process? What are my potential vulnerabilities? Could costly claims be avoided by not providing certain goods or services?

- Identify and analyze risks: Analyze each dimension of the prescribing process and identify the associated risk. Identify and analyze the type of prescriptive authority and the risks involved in each.

- Evaluate and prioritize the risks:Every risk cannot be addressed at one time. Prioritize managing risks that have the greatest potential to result in substantial losses.

- Select an appropriate risk management strategy: Determine which risks could (and should) be avoided. Policies and procedures should be developed for appropriate risk prevention measures. Insurance policies should be secured as necessary.

Figure 1. Risk Management Process for Prescribing14

There are a few different types of techniques to manage risk. A pharmacist may choose to avoid the risk altogether which is known as risk avoidance.14 An example of this would be a pharmacist who is not comfortable managing diabetes patients therefore would choose to limit entering any type of prescriptive authority agreement involved with the diabetic patient population. Risk prevention/modification involves the development of policies and procedures to prevent errors and improve patient safety.14 Consider that the pharmacist in the previous example decides to work with diabetic patients. In order to modify risk, the pharmacist takes a course to become a diabetes certified educator and proceeds to implement a prescribing policy for managing diabetic patients. Another technique to manage risk is to share the risk with another party (risk sharing).14 In this case, if a pharmacist is not comfortable with autonomous prescribing, they may decide to enter into a collaborative practice agreement with a physician. Recall that in this type of prescribing agreement the physician traditionally maintains oversight of the services provided through some mechanism, such as auditing patient records to ensure protocols are being followed in turn contributing to sharing risk. Each risk should be evaluated individually as to which technique(s) would be the most appropriate for that given risk.

Liability Insurance

No matter how careful a pharmacist is about preventing risks, it is practically impossible to eliminate risks. In some unfortunate occasions an error will occur, and litigation may follow. In these situations, insurance policies will be required to provide adequate risk protection for the employer and employee. If you work for an employer, they will typically have several different types of insurance policies. Property insurance is one of the most common types of insurance for protecting the property and physical assets of any business entity. These policies cover losses due to fire, lightning, or theft and the cost of removing property to protect it from further harm. Your employer will also carry their own liability insurance which protects the business entity against claims when it is sued for damages or injuries caused by the negligence of the business or its employees. This type of insurance will cover any damage or injury as well as the legal expenses involved in a negligence suit.14

If a pharmacist is involved in prescribing, they should consider purchasing individual professional liability insurance policies in addition to what their employer may provide. This will protect the individual against claims stemming from actual or alleged errors or omissions, including negligence, during professional duties or activities. Often individuals purchase a policy because the employers’ policy limits are not high enough or they are not covered if practicing outside of that workplace. In deciding whether to purchase personal liability insurance it is important to consider that the employer has purchased their own insurance to negotiate on their behalf. A defense team representing the employer may claim the employee violated company policy thereby absolving the employer of any liability. In this case, the claim would fall on the individual pharmacist.14 Any practicing pharmacist no matter the scope of practice should consider purchasing liability insurance regardless of what is provided by the employer. The American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) and American Pharmacist Association (APhA) both offer insurance products including professional liability coverage. As pharmacists take on increasing professional responsibility, the successful clinician must successfully minimize and manage risks associated with these added responsibilities including appropriate risk management strategies and insurance coverage.

CONCLUSION

Certainly, one must consider that just obtaining a pharmacist license does not mean you are competent or comfortable in prescribing medications. This is important to consider from both a societal and personal perspective. Many states place requirements on pharmacists who enter into prescribing agreements. These have included earning certification in a respective area of practice, completing a residency program, specific continuing education programs, or previous experience with a collaborative practice agreement prior to autonomous prescribing.1,16 Board certification in a specialty area signifies the individual has gained additional knowledge, skills and experience in a defined area within pharmacy practice. Board certification is a way of demonstrating to society that an individual possesses a certain high level of expertise in addition to that of a general practitioner. Before entering into a practice agreement, a pharmacist may consider becoming board certified to gain additional knowledge and skills.

Prescribing pharmacists play a vital role in the delivery of high-quality healthcare services and are well placed to use their knowledge of medications in the various new roles which are being developed and integrated into care models. In order to prescribe safely and effectively, pharmacists should have access to all relevant patient medical records as well as prescribe according to national and clinical guidelines. In addition, pharmacists must prescribe within the limits of their knowledge, skills and area of competence as well as complying with the legal constraints of their state. Appropriate procedures to identify and manage the risks involved in providing and managing prescribing pharmacy service are critical to not only provide best care for the patient but to limit their own personal and professional liability. The profession of pharmacy is evolving extremely rapidly to meet the changing needs of society and a pharmacist has the potential to make a positive difference in the lives of patients by having an active role in prescribing.

REFERENCES

- Adams A, Weaver K. The continuum of pharmacist prescriptive authority. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(9):778–84.

- Stimmel G. Political and legal aspects of pharmacist prescribing. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1983;40(8):1343-44.

- Carmichael J, O’Connell MB, Devine B, et al. Collaborative drug therapy management by pharmacists. 1997;17(5):1050-61.

- Adams A, Klepser M, Klepser D. Physician-pharmacist collaborative practice agreements: a strategy to improve adherence to evidence-based guidelines. Evid Based Med Public Health. 2015;1:e923.

- Pollock M, Bazaldua O, Dobbie A. Appropriate prescribing of medications: an eight-step approach. Am Fam Physician.2007;75(2):231-36.

- World Health Organization Action Program on Essential Drugs. Guide to Good Prescribing. Accessed November 13, 2020 from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/59001/WHO_DAP_94.11.pdf?sequence=1.

- Wolters Kluwer. Grading Guide. Accessed November 13, 2020 from https://www.uptodate.com/home/grading-guide.

- Surrogate Endpoint Resources for Drug and Biologic Development. Accessed November 14, 2020 from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/surrogate-endpoint-resources-drug-and-biologic-development.

- The FDA’s Drug Review Process: Ensuring Drugs are Safe and Effective. Accessed November 14, 2020 from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-information-consumers/fdas-drug-review-process-ensuring-drugs-are-safe-and-effective.

- Hartman M, Martin A, Espinosa N, et al. National health care spending in 2016: spending and enrollment growth slow after initial coverage expansions. Health Aff. 2018;37(1):150-60.

- Cuckler G, Sisko A, Poisal J, et al. National health expenditure projections 2017-26: despite uncertainty, fundamentals primarily drive spending growth. Health Aff. 2018;37(3):482-92.

- Marlow F. Do cholinesterase inhibitors slow progression of Alzheimer’s disease? Int J of Clin Practice. 2002;127(127):37-44.

- Weissman F, Pinder J, Berns M. Pharmacy Practice and Tort Law. Background to Negligence in Pharmacy Practice: Elements of Negligence (Part I). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 20

- Alston G, Boone S. Pharmacy Management: Essentials for All Practice Settings.5thRisk Management in Contemporary Pharmacy Practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2020.

- Poh E, McArthur A, Stephenson M, Roughead E. Effects of pharmacist prescribing on patient outcomes in the hospital setting: a systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2018;16(9):1823-73.

- Majercak K. Advancing pharmacist prescribing privileges: is it time? J Am Pharms Assoc. 2019; 59(6):783-86.

Back to Top