Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Medication Safety: Practical Approaches to Preventing Medication Errors in Health System Pharmacy

“Because of the immense variety and complexity of medications now available, it is impossible for nurses and doctors to keep up with all of the information required for safe medication use. The pharmacist has become an essential resource…and thus access to his or her expertise must be possible at all times.”

—Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. 2000.1

In the two decades since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released its landmark report providing recommendations for addressing medication errors, the focus on medication safety continues. A recent meta-analysis of studies spanning from 2000 to 2019 suggest one in 20 patients are exposed to preventable harm in medical care with 25% of incidents being medication-related.2 Medication errors impact an estimated 1.5 million people every year.3 In 2019, Americans filled 5.96 billion prescriptions (30-day equivalent)4 which would result in an estimated 93,600,000 errors given a medication dispensing error rate of 1.57%.5,6 A 2016 study from Johns Hopkins reported that 10% of all deaths in the United States are caused by medical errors, leading the authors to rank them the third-leading cause of death — up from the tenth leading cause when the IOM report was published (based on 1984 data).7 The burden of medication errors is high. Costs of treating drug-related injuries in hospitals are $3.5 billion a year,3 and the morbidity and mortality associated with medication errors is estimated to be $77 billion each year.8 Beyond economic costs, errors are costly in terms of patients’ loss of trust, reduced satisfaction and physical and psychological discomfort. They are costly as health professionals lose morale and frustration at providing less than optimal care.1 Continued efforts to address medication error causes are critical to improve medication safety, public health and reduce patient harm. Pharmacists and the pharmacy team have important roles to play in preventing medication errors throughout the health system.

In his preface in “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” Chair William Richardson notes, “The title of this report encapsulates its purpose. Human beings, in all lines of work, make errors. Errors can be prevented by designing systems that make it hard for people to do the wrong thing and easy for people to do the right thing.”1 No practitioner goes to their practice site with intention to do harm or make errors. However, sometimes there are weaknesses in the system that allow errors to happen. Creating safer systems within healthcare organizations by designing and implementing safe practices for healthcare delivery was the ultimate target of all IOM recommendations. That focus continues today. Within pharmacy, this may include attention to various components of the medication use process including but not limited to policies and procedures, workflow, computer systems, physical environment, and staffing. Within health systems, pharmacists should be part of any multidisciplinary structures that address the organization’s medication use processes.9

What are Medication Errors?

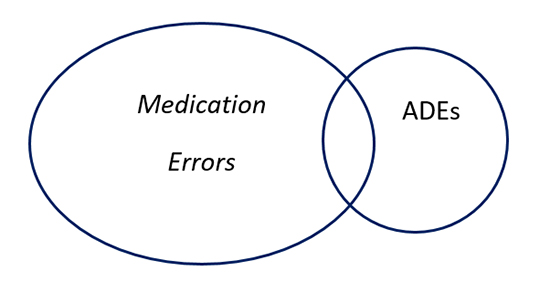

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error and Prevention (NCCMERP) defines a medication error as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, healthcare products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing, order communication, product labeling, packaging, and nomenclature, compounding, dispensing, distribution, administration, education, monitoring, and use."10 Not all medication errors cause harm. When they do, they may be called adverse drug events (ADEs) which are a subset of medication errors and are defined as “an injury resulting from medical intervention related to a drug.”1 See figure 1.

Figure 1: Relationship of Adverse Drug Events and Medication Errors

ADEs

Errors may fall into several categories, including errors of omission, commission and system errors.11 Errors of omission are generally when something has not been done right, for example, failure to check patient allergies or incorrect medication reconciliation. Errors of commission are when something has been done wrong, for example, dispensing the incorrect medication, providing the wrong dose or instructions or incorrectly transcribing during medication reconciliation. System errors are those not exclusively because of an individual’s action, for example environmental factors that distract pharmacy team members during the medication use process. See Table 1 for other examples of each.

| Table 1. Type of Errors11 |

| Definition |

Examples |

| Omission: an error resulting in an inappropriate increased risk of disease-related adverse event(s) resulting from receiving too little treatment (underuse). |

Errors of omission include problems such as failure to include all prescriber instructions, subtherapeutic doses of medications, failure to check patient allergies or to counsel on medication. |

| Commission: an error resulting in an inappropriate increased risk of iatrogenic adverse event(s) from receiving too much or hazardous treatment (overuse or misuse). |

Errors of commission include problems such as too much medication, treatments that are contraindicated, inadvertently giving the wrong medication, or overriding a medication alert. |

| System Error: an error resulting from actions or factors that are part of a process, not just attributable exclusively to an individual’s actions alone. |

System errors include problems such as inadequate lighting, lack of double checks, no policies on double checking patient names/birthdays that result in errors. |

Addressing medication errors requires an understanding of how and why they occur during the medication-use process. The Joint Commission (JCAHO) has incorporated medication safety and management into their standards and accreditation process. Helpful guidance documents have been developed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) for preventing medication errors that incorporate the Joint Commission’s medication management system.9 See Table 2.

| Table 2. ASHP’s Modified Medication Management System |

| System Elements |

| Planning |

| Selection and procurement |

| Storage |

| Patient admission |

| Ordering, transcribing, and reviewing |

| Preparing |

| Dispensing |

| Administration |

| Monitoring |

| Patient discharge |

| Evaluation |

| Adapted from Figure 1 in ASHP Guidelines on Preventing Medication Errors in Hospitals |

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) is a 501c (3) nonprofit organization devoted entirely to preventing medication errors. In the past 25 years, ISMP has provided tools and resources for healthcare professionals to help prevent errors and has defined “Key Elements of the Medication-Use System™.” 12 ISMP notes that “Medication use is a complex process that comprises the sub-processes of medication prescribing, order processing, dispensing, administration, and effects monitoring.” Each component may be associated with medication errors as outlined in Table 3.

Both these frameworks provide a useful construct to think about where medication errors can occur and ways to minimize risk within each area.

| Table 3. ISMP’s Key Elements of the Medication-Use System |

| Element |

Error Potential |

| Patient information |

Failure to obtain patient’s demographic (age, weight) and clinical information (allergies) |

| Drug information |

Failure to provide accurate and useable drug information |

| Communication of drug information |

Miscommunication between prescriber, nurse and pharmacist |

| Drug labeling, packaging and nomenclature |

Look-alike, sound-alike names, confusing drug labeling and/or packaging |

| Drug storage, stock, standardization and distribution |

Poor shelf labels, not separating dosage forms on shelves, lack of standardized drug concentrations |

| Drug device acquisition, use and monitoring |

No safety assessments for drug delivery devices or independent double checks, not providing dosage tools/devices |

| Environmental factors |

Poor lighting, noise, interruptions, workload |

| Staff competency and education |

Not focusing on appropriate education, i.e. high-alert medications, policies and processes for medication safety |

| Patient education |

Failure to counsel on medication indications, doses, drug or food interactions, adverse effects, how to protect from errors |

| Quality processes and risk management |

Not analyzing medication error causes and having a system of detecting and preventing errors |

| This table has been adapted with permission from ISMP. https://www.ismp.org/ten-key-elements. |

Medication Safety Planning & Risk Reduction

Creating safe medication practices begins with making medication safety a priority within the institution and the pharmacy, including creating a culture throughout all levels of the organization that supports patient safety. The institution should have a comprehensive program that includes a medication safety strategic plan which is usually stewarded by an interdisciplinary medication safety team under the leadership of a medication safety leader.9 ASHP outlines the role of the medication safety leader in a detailed statement.13 That role includes responsibility for leadership, medication safety expertise, influencing practice change, research and education.13 Medication safety leaders should be strategically positioned to lead efforts to improve medication safety. The medication safety team should be multidisciplinary and take a collaborative and systematic approach to risk assessment and medication error analysis, including adopting technologies that can minimize the risk of errors.9 ISMP suggests the team consist of the following or similar14:

- Senior facility leader

- Chief medical leader

- Chief nurse leader

- At least one (outpatient) or two (inpatient) nurses

- At least one (outpatient) or two (inpatient) staff physicians

- Pharmacy director

- Two staff pharmacists

- Clinical information technology specialist

- Medication safety or patient safety officer/manager

- Risk management and quality improvement professionals

A supportive culture allows the medication safety team to operate at is best and encourages team members to speak up about safety issues and feel comfortable when errors are found and need to be addressed. It is an environment where team members should feel comfortable learning from errors in order to identify causes and prevent their recurrence. Incident reporting should focus on system improvement not blaming individuals for actions that may contribute to medication errors. A supportive culture also provides support to “second victims,” who are the healthcare providers who are involved in an unintended adverse event that may be traumatized by it.15 Programs to support second victims should be developed and included in staff training programs. Education and training can help reduce the risk of medication errors, and a number of states require pharmacists to include medication safety in their continuing education requirements.16

In addition to staff competency and education, having quality improvement processes and risk management procedures in place to detect, analyze and prevent medication errors is an element of safe medication use.9 Errors and close calls should be reported and analyzed using root cause analysis (RCA) and similar tools. Besides reporting, other error detection methods can be employed including chart review and data mining. More detail will be provided in the evaluation section of this lesson.

Risk Assessment

An important part of the planning process is assessing risk. Conducting risk assessments will help the organization identify issues that could lead to problems and allow them to be prioritized and addressed. The ISMP has a number of self-assessment and other tools available for organizations to use to assess the risk of medication errors. ISMP notes the tools can help organizations:17

- Proactively assess medication use processes

- Identify safety risks

- Drive critical, honest discussion around current safety practices

- Create an action plan for improvement

- Track progress as recommended system-based strategies are implemented

ISMP tools that hospital and health-system pharmacies may find useful include:

- Medication Safety Self-Assessment ® for Hospitals

- Medication Safety Self-Assessment® for Perioperative Settings. Release in early 2021.

- Medication Safety Self-Assessment® for High-Alert Medications

- Assess-ERR™ Medication System Worksheets

More information about the tools may be found in Table 4. ASHP also provides a useful self-assessment checklist as part of their guidelines on preventing errors in appendix B.9

| Table 4. ISMP Assessment Tools |

| Tool |

Goals |

Notes |

Cost |

| Medication Safety Self-Assessment ® for Hospitals |

- Heighten awareness of distinguishing systems and practices in a safe hospital medication system.

- Assist interdisciplinary teams with proactively identifying opportunities for reducing patient harm when prescribing, storing, preparing, dispensing, and administering medications

- Create a baseline of efforts to evaluate risk and evaluate efforts over time

|

Follows ISMP's Key Elements of the Medication Use System™.

Each core characteristic contains individual self-assessment items to help evaluate the medication safety strategies in the organization. |

Complimentary. Grant supported by The Commonwealth Fund. |

| Medication Safety Self-Assessment® for Perioperative Settings. Release in early 2021. |

- Heighten awareness of safe practices in Perioperative Settings.

- Assist interdisciplinary teams with proactively identifying and prioritizing facility-specific gaps in perioperative medication systems to avoid patient harm

- Create a baseline of efforts to evaluate perioperative medication safety and measure your progress over time

- Help analyze the current state of medication safety in perioperative settings and create a baseline measure of national efforts

|

Designed for hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), and other surgical sites. Tools to help document compliance with The Joint Commission’s requirement for conducting a proactive risk assessment on a high-volume, high-risk, or problem-prone process, as well as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requirement for developing a data-driven quality assessment and performance improvement program. |

Complimentary. Funded by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under contract #75F40119C1020. |

| Medication Safety Self-Assessment® for High-Alert Medications |

- Heighten awareness of distinguishing systems and practices related to the safe use of 11 categories of high-alert medications

- Assist interdisciplinary teams with proactively identifying opportunities for reducing patient harm when prescribing, storing, preparing, dispensing, and administering high-alert medications

- Create a baseline of efforts to evaluate risk and evaluate efforts over time

- Determine the challenges healthcare providers face in keeping patients safe during high-alert medication use

|

Allows organizations to assess current practices and systems associated with prescribing, dispensing, and

administering high-alert medications. Helps them identify specific challenges, prioritize opportunities for improvement, and track experiences

over time. Can help meet or gauge compliance with managing high-alert medications as

required by various state and federal regulatory agencies, such as The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. |

Complimentary. Funded and supported by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under contract #HHSF223201510136C. |

| Assess-ERR™ Medication System Worksheets |

- Employ this tool to help identify, prioritize, and record problems in the organization’s medication use system.

- Aid in developing a standardized approach to documenting error incidents

- Helps to reveal the underlying system deficiencies that contributed to the error.

- Raise awareness of issues that have become so familiar to healthcare practitioners in a particular practice setting that the issues are no longer even recognized as risks.

|

Designed to help with error report investigations. Worksheets used to collect critical information after a medication error or near-miss occurs.

Can help convert a negative error experience into a positive learning experience that enhances safety. |

Complimentary. |

ISMP also offers numerous other best practice tools for use in the acute care setting, including18:

- Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices for Hospitals, consensus-based best practices for issues that continue to cause fatal and harmful errors.

- Guidelines for Optimizing Safe Implementation and Use of Smart Infusion Pumps, developed in 2020 to help healthcare facilities standardize smart infusion pump technology.

- Guidelines for the Safe Use of Automated Dispensing Cabinets, standard best practices and processes directly associated with ADC design and functionality.

- Guidelines for Safe Electronic Communication of Medication Information, strategies to safely present drug information in various electronic formats.

- Guidelines for Optimizing Safe Subcutaneous Insulin Use in Adults, address at-risk behaviors and unsafe practices in the inpatient setting and during transitions of care.

- Guidelines for Safe Preparation of Compounded Sterile Preparations, prevent errors during pharmacy preparation of parenteral admixtures.

- Safe Practice Guidelines for Adult IV Push Medications, best practice recommendations to standardize safe administration of parenteral IV push medications.

- Guidelines for Timely Administration of Scheduled Medications (Acute), for acute care organizations developing or revising policies and procedures.

- Guidelines for Standard Order Sets, incorporate these elements when designing paper-based or electronic order sets.

Risk Reduction

Risk reduction strategies should focus on high-risk populations, processes, look-alike and sound-alike (LASA) medications and high-alert medications throughout the organization.9 LASA medications may be easily confused due to similarities in name, packaging, or dosage form. These medications should be separated where they are in the organization using color or tall man letters. The ISMP maintains a list of look-alike drug names with tall man letters.19 There are two lists: one of FDA-approved generic drug names with tall man letters and an ISMP list of additional drug names with tall man letters. Examples of each list may be found in Table 5. These lists have now been included in ISMP’s list of confused drug names, providing a consolidated reference to use with the pharmacy team.20 Including indications for use on orders can also help address errors related to LASAs.

| Table 5. Examples of Look-Alike Drug Names with Tall Man Letters |

| Drug Name with Tall Man Letters |

Confused With |

| amLODIPine |

aMILoride |

| CeleBREX |

CeleXA |

| cycloSPORINE |

cycloSERINE |

| DAUNOrubicin |

DOXOrubicin |

| glyBURIDE |

glipiZIDE |

| HumuLIN |

HumaLOG |

| hydrALAZINE |

hydrOXYzine – HYDROmorphone |

| lamoTRIgine |

lamiVUDine |

| oxyMORphone |

HYDROmorphone – oxyCODONE – OxyCONTIN |

| PARoxetine |

FLUoxetine – DULoxetine |

| prednisoLONE |

predniSONE |

| QUEtiapine |

OLANZapine |

| risperiDONE |

rOPINIRole |

| traMADol |

traZODone |

| vinBLAStine |

vinCRIStine |

| This table has been adapted with permission from ISMP. https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2017-11/tallmanletters.pdf |

In addition to sound-alike and look-alike medications, high-risk medications should be flagged with additional care taken to ensure the correct medication has been selected with the correct dosage. High-alert medications are drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when they are used in error. ISMP maintains lists of high-alert medications for both the acute care and community/ambulatory pharmacy settings. An example of these medication classes in the acute care environment includes21:

- Adrenergic agonists, IV (e.g. epinephrine, phenylephrine, norepinephrine)

- Adrenergic antagonists, IV (e.g. propranolol, metoprolol, labetalol)

- Anesthetic agents, general, inhaled and IV (e.g. propofol, ketamine)

- Antiarrhythmics, IV (e.g. lidocaine, amiodarone)

- Antithrombotic agents, including anticoagulants (e.g. warfarin, heparin, new direct acting oral anticoagulants, glycoprotein inhibitors, thrombolytics)

- Cardioplegic solutions

- Chemotherapy agents

- Dextrose, hypertonic, 20% or greater

- Dialysis solutions, peritoneal and hemodialysis

- Epidural and intrathecal medications

- Inotropic medications, IV (e.g. digoxin, milrinone)

- Insulins and oral hypoglycemic agents

- Liposomal forms of drugs and conventional counterparts

- Moderate sedation agents, IV

- Moderate and minimal sedation agents, oral

- Opioids

- Neuromuscular blocking agents (e.g. succinylcholine, rocuronium, vecuronium)

- Parenteral nutrition preparations

- Sodium chloride for injection, hypertonic, greater than 0.9% concentration

- Sterile water for injection, inhalation and irrigation in containers of 100 mL or more

ISMP suggests using auxiliary labels, shelf labels and automated alerts and standardizing the storage, dispensing and administration of these products.21 Additionally, ASHP has created a list of risk reduction strategies that have proven effective related to high-risk medications as part of their guidelines for preventing errors.9

Common Medication Errors and Causes

As providers, our goal may be to meet the “five rights” of medication administration:22

- Right patient

- Right drug

- Right dose

- Right route

- Right time

ISMP has said that merely focusing on the five rights, however, is “not the “be all that ends all” in medication safety.”23 Rather they are broadly stated goals or desired outcomes of safe medication practices but they do not focus on human factors and system defects that may make completing the tasks difficult or not possible. ISMP says, “…the healthcare practitioners’ duty is not so much to achieve the five rights, but to follow the procedural rules designed by the organization to produce these outcomes. And if the procedural rules cannot be followed because of system issues, healthcare practitioners also have a duty to report the problem so it can be remedied.”

Errors can occur throughout the medication use process including:

- Selection and procurement

- Storage

- Patient admission

- Prescribing/order communication

- Transcribing/reviewing

- Preparing

- Dispensing

- Administering

- Monitoring

A recent analysis of pharmacist liability claims provides Insights on medication error types and causes.24 Among 184 paid claims among 428 incidents between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2016, the distribution of errors is shown in Table 6, including a comparison to the 2013 analysis which had 164 paid claims among 734 incidents during a 10-year period from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2011.24

| Table 6: Distribution of Liability Claim Errors24 |

| Claim Error |

Percentage of Occurrence |

| |

2018 |

2013 |

| Wrong drug |

36.8 |

43.8 |

| Wrong dose |

15.3 |

31.5 |

| Contamination of drug/container/equipment |

14.1 |

0.6 |

| Failure to consult with prescriber on question/concern |

5.5 |

4.9 |

| Prescription given to wrong patient |

5.5 |

3.1 |

| Compounding calculation and/or preparation error |

5.0 |

3.7 |

| Failure to obtain/review laboratory values required for proper dosing |

2.8 |

0.0 |

| Labeling error |

2.2 |

0.0 |

| Failure to provide instructions/wrong instructions |

1.7 |

0.0 |

| Failure to supervise |

1.7 |

0.0 |

Several categories saw declines in claims (wrong drug, wrong dose) while others posted gains, including contamination and preparation errors, failures to consult prescribers, failure to consult laboratory values, wrong patient, wrong instructions and labeling errors.24 Consequences of these errors is significant and shown in Table 7.

| Table 7: Severity and Cost Associated with Liability Claims24 |

| Error Outcome |

Percentage of Occurrence (%) |

Average Claim Cost Incurred ($) |

| Patient death |

11.3 |

298,557 |

| Intervention to save patient’s life |

2.8 |

291,615 |

| Permanent patient harm |

17.4 |

274,873 |

| Error reached patient, no harm |

1.6 |

102,833 |

| Temporary patient harm requiring intervention/prolonged hospitalization |

41.3 |

72,577 |

| No medication error |

1.1 |

28,750 |

| Patient monitoring required to confirm no harm or intervention needed |

1.1 |

19,322 |

| Temporary patient harm requiring intervention |

23.4 |

10,387 |

Factors associated with these liability claims reflect failures in one or more of the medication use processes as outlined in Table 8. These include storage and quality process issues, patient information, education and monitoring issues and failure to check with the prescriber.

| Table 8. Factors Associated with Wrong Drug Dispensing Error Claims24 |

| Claim Error |

Percentage of Occurrence |

| |

2018 |

2013 |

| Failure to separate sound-alike drugs using color/separation/tall man letters |

15.1 |

18.5 |

| Failure to check drug against label and actual prescription |

9.8 |

10.5 |

| No explanation or underlying error cause |

6.5 |

2.5 |

| Failure to review prescription with patient |

1.7 |

0.6 |

| Failure to separate look-alike drugs using color/separation/tall man letters |

1.1 |

1.2 |

| Failure to consider patient history/profile/drug therapies |

1.1 |

0.6 |

| Failure to question prescriber about unusual numbers/amounts of controlled drugs |

0.5 |

1.2 |

| Failure to monitor and clarify anticoagulant dose |

0.5 |

0.6 |

| Failure to monitor and clarify controlled substance prescription |

0.5 |

0.6 |

Claim analysis by pharmacy type showed that pharmacist paid claims in the hospital setting were more than two times that of the average claim incurred, $273,338 vs. $124,407, respectively.24 Hospitals represented 8.2% of paid claims.24 Allegations associated with the highest paid claims were:

- Failure to identify overdosing;

- Compounding calculation and/or preparation error;

- Libel/slander;

- Failure to provide instructions;

- Contamination of drug/container/equipment; and,

- Failure to counsel patient.

Understanding how and where medication errors occur in the medication management system can help the medication safety leader and the medication safety team focus their risk assessment and reduction measures.

Selection and Procurement

The selection and procurement of medications includes the formulary management process, use of standard concentrations, monitoring of medication safety alerts, safe procurement practices and drug shortage management.9

The formulary management process allows providers to prescribe safe, cost-effective medications and become familiar with formulary medication dosing, preparation/dispensing and administration. A set formulary will also allow standardization of support systems such as electronic health record (EHR) systems, order sets, medication information systems, infusion pump settings and automating dispensing cabinet contents. ASHP’s guideline offers detailed questions to ask when adding new medications to the organization’s formulary.9

Limiting and standardizing the number of medication concentrations available contributes to avoiding errors in calculations, reducing waste, efficiently managing inventory and help promote use of pre-mixed solutions. The Standardize 4 Safety initiative between ASHP and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is a national, interprofessional effort to standardize medication concentrations to reduce errors, especially during transitions of care by establishing standardized concentrations for intravenous and oral liquid medications for patients of all ages in settings ranging from hospital to home.25

Designated members of the pharmacy team should be assigned to actively monitor medication safety alerts. This includes monitoring the organization’s error reporting program and accessing national error reporting programs. The National Alert Network (NAN) is a coalition of members of the NCC MERP; it should be monitored for urgent advisories, which are distributed by ISMP and ASHP. ISMP has a subscription e-newsletter, The ISMP Medication Safety Alert!® Acute Care, published every two weeks for hospital healthcare professionals.26

Safe procurement practices include having the pharmacy department responsible for all procurement within the organization, including how to handle patient’s home medications and samples. Pharmacists should be part of any team that evaluates devices related to medication use. Part of safe procurement includes effective management of drug shortages, including communication to the team. ASHP also has guidelines for drug shortage management27 The FDA’s drug shortage portal is also a useful resource, accessible at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/drug-shortages.

Patient Admission

There are several best practices that can help prevent medication errors, including medication reconciliation to obtain an accurate medication history within the organization’s required timeframe, especially for high alert medications. Weighing each patient as soon as possible after admission with accurate documentation in the metric system and avoiding any historical or estimated weight is a best practice.28 Verifying and documenting the patient’s opioid status (naïve vs. tolerant) and whether the patient is experiencing acute or chronic pain is also a best practice.28

Prescribing/Order Communication Errors

Prescribing errors contribute to medication errors and may include issues with:

- Illegibility

- Inappropriate abbreviation

- Directions

- Strength

- Dose

- Length of treatment

- Frequency

- Amount

Prescribers need to be familiar with the organization’s medication ordering system, and orders should follow hospital policy. Orders should include patient identifiers, generic and trade name of medication (if required), route and site of administration, dosage form, strength, quantity, administration frequency, duration of treatment, indication for use and the prescriber’s name. For IV medications, the concentration, rate and time of administration should be specified.

The Role of E-Prescribing and Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE)

E-prescribing and CPOE have been shown to decrease prescribing errors, increase efficiency, decrease patient abandonment of prescriptions and help save healthcare costs.29,30,31 A systematic review of 25 studies that analyzed the effects of e-prescribing on the medication error rate, found a significant relative risk reduction of 13% to 99%.29 E-prescribing has grown significantly in the years since its introduction and more than half the states require it for opioids, controlled substances or all prescriptions.32 In 2019, 80% of all prescriptions were e-prescribed, while the rate for controlled substances was 38%. E-prescribing systems also allow clinical messages to be communicated between health providers, including managing prior authorizations electronically.

Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) in institutions can help reduce errors. A meta-analysis showed processing a prescription drug order through a CPOE system decreases the likelihood of error on that order by 48%. Researchers estimate a 12.5% reduction in medication errors, or ∼17.4 million medication errors averted in the USA in one year through the use of these systems.31

While electronic prescribing has many benefits, errors within the process can still occur. A recent study reviewed 25,000 e-prescriptions issued by 22,152 community-based prescribers in the United States.33 Over 500 different electronic health record (EHR) systems were used to generate the e-prescriptions. Significant variance among the Sig text strings were found and 10% of Sigs contained quality-related events that could pose risks to patient safety or require workflow disruptions when Sig clarification is needed.33 Adoption of national e-prescribing standards by EHR vendors, improved usability and end-user training are recommended to address these issues. Within hospitals, standardized orders sets that integrate best practices and evidence should be used in EHRs and CPOE systems.

Transcribing/Reviewing

In addition, there are actions the pharmacy team can take to reduce errors associated with ordering systems. These include:

- Regarding any unclear orders as potential errors until clarification is received from the prescriber and having policies to clarify orders before the prescriber leaves the patient care unit.9

- Reviewing the medication order for appropriateness

- Verifying the name, birthdate and address of the patient and being alert for potential similar patient records

- Staying vigilant with similar drug names and different dosage and salt forms of medications, including extended or sustained release vs. immediate release and ensuring compliance with formulary

- Reviewing carefully the Sig instructions for the medication ordered per standard order set

- Verifying the physician’s name, office location and credentials

- Entering notes into the fill or patient records to clarify any issues with the order and to ensure continuity of care

There will still be times when orders are provided verbally, presented manually in written form or sent to the pharmacy outside CPOE systems. There are strategies that the pharmacy team can employ to help reduce the possibility of errors, including:

- Complete the transcription process in a quiet, well-lit area free from distractions.9

- Review each order to be sure it includes these elements:34

- Name of patient

- Age and weight of patient

- Drug name

- Dosage form (e.g., liquid, tablets, capsules, inhalants)

- Exact strength, dose or concentration

- Dose, frequency, and route (including the dose basis for pediatric patients)

- Quantity and/or duration

- Purpose or indication (unless disclosure is considered inappropriate by the prescriber)

- Specific instructions for use, not use as directed

- Name of prescriber—and telephone number, when appropriate

- Name of individual transmitting the order, if different from the prescriber

- Use templates containing all elements of ideal order.

- For verbal orders read back the prescription to the person giving the order.

- Write neatly, print is preferable.

- Prescriptions should be written using the metric system, not the older apothecary or avoirdupois systems.

- Prescriptions should include leading zeros, used before a decimal quantity less than one, e.g. write 0.1 not .1. Trailing zeros should NOT be used after a decimal. e.g. write 1 not 1.0.

- Prescriptions should not contain abbreviations. The Joint Commission has a list of abbreviations that should never be used, see Table 9.35

| Table 9. The Joint Commission Official “Do Not Use” List35 |

| Do Not Use |

Potential Problem |

Use Instead |

| U (unit) |

Mistaken for “0” (zero), the

number “4” (four) or “cc” |

Write “unit” |

| IU (international unit) |

Mistaken for IV (intravenous)

or the number 10 (ten) |

Write “international unit” |

| Q.D., QD, q.d., qd (daily) |

Mistaken for each other

Period after the Q mistaken for

"I" and the "O" mistaken for "I" |

Write “daily” |

| W.O.D., QOD, q.o.d., qod (every other day) |

Mistaken for each other

Period after the Q mistaken for

"I" and the "O" mistaken for "I" |

Write “every other day” |

Trailing zero (X.0 mg)

Lack of leading zero (.X mg) |

Decimal point is missed |

Write X mg

Write 0.X mg |

| MS |

Can mean morphine sulfate or

magnesium sulfate

Confused for one another |

Write “morphine sulfate” |

| MSO4 and MgSO4 |

Can mean morphine sulfate or

magnesium sulfate

Confused for one another |

Write “magnesium sulfate” |

| Additional Abbreviations for possible future inclusion |

| Do Not Use |

Potential Problem |

Use Instead |

>(greater than)

<(less than) |

Misinterpreted as the number

“7” (seven) or the letter “L”

Confused for one another |

Write “greater than”

Write “less than” |

| Abbreviations for drug names |

Misinterpreted due to similar

abbreviations for

multiple drugs |

Write drug names in full |

| Apothecary units |

Unfamiliar to many

practitioners

Confused with metric units |

Use metric units |

| @ |

Mistaken for the number

“2” (two) |

Write “at” |

| cc |

Mistaken for U (units) when

poorly written |

Write “mL” or “ml” or “milliliters” |

| µg |

Mistaken for mg (milligrams)

resulting in one thousand-fold

overdose |

Write “mcg” or “micrograms” |

Preparation

Preparing medication orders should occur under proper conditions, including temperature, light, humidity, ventilation, segregation and security. Independent double checks are a best practice. The double check should include verifying ingredients used, the quantities of each, expiration dates, and preparation instructions which ISMP recommends occur before the preparation is finalized.28 Maximizing standard concentrations and use of ready-to-administer or unit-of-use packaging is preferred.28 All preparation should follow USP processes and procedures for sterile and non-sterile compounding, USP Chapter <797> and USP Chapter <795>, respectively, and for compounding hazardous medications, USP Chapter <800>. All can be downloaded complimentary at: https://go.usp.org/l/323321/2020-03-09/3125jw. ISMP and ASHP also have guidelines on sterile compounding.18,36

Efforts should be made to ensure medication preparation occurs in the pharmacy and is minimized elsewhere in the organization. ISMP recently conducted a survey about admixing sterile injectables and infusions in patient care areas among 444 nurses, anesthesia providers and anesthesiologists in acute care and hospital settings and found significant safety challenges.37 Respondents indicated the most common types of sterile injections prepared outside the pharmacy were:

- IV push medications, mostly medications transferred from vials to syringes (e.g., opioids, antiemetics, antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors)

- IV intermittent infusions, mostly minibag diluent containers with an integral vial adapter for the medication vial

- IM injections, mostly vaccines, antipsychotics, and antibiotics (these may involve mixing a drug powder and then transferring into a syringe)

More than three-fourths of the respondents indicated that admixing occurs in less than ideal conditions at times, such as at the patient’s bedside (38%), on a counter or at the nursing station (28%), and on a mobile computer workstation (16%). Only 35% of all respondents reported that they were required to have another practitioner independently double check that certain medications and infusions were properly admixed prior to administration.37 Most, however, said that all (30%) or certain (44%) high alert medications required an independent double check. The most common errors personally experienced by respondents included wrong technique (21%), incorrect diluent/volume (20%), incorrect dose/concentration (19%) and labeling errors (19%). Feeling rushed through the admixing process, especially during emergencies that required the use of high alert medications, while feeling pressured to follow standards established for routine care during urgent situations was the most commonly cited safety challenge.37 Constant interruptions and distractions and concern about the sterility of the preparation area, process and end product were also cited.37 Survey results support the best practice of minimizing preparation outside of the pharmacy.

Dispensing Errors

In spite of a reduction in wrong drug/wrong dose errors in pharmacist liability claims from 2013 to 2018, errors involving the wrong drug/wrong dose still have the highest occurrences (36.8% and 15.3%, accordingly) among claims and are four-times more costly than the average claim amount incurred. 24 A primary contributor to wrong drug errors is failure to take special precautions with sound-alike and look-alike drugs (15.1%).24

These issues are reflected in ISMP’s top medical errors reported to the organization in 201938:

- Daily instead of weekly methotrexate for nononcologic conditions.

- One-thousand-fold overdoses with zinc due to insufficient critical dose warnings for IV zinc and other trace elements use as parenteral nutrition additives, especially in pediatric patients.

- Errors and hazards due to look-alike and sound-alike drugs, most recently look-alike labeling from one manufacturer resulting in recalls for tranexamic acid, deferoxamine mesylate, midazolam, vancomycin, ketorolac among the manufacturer’s other products.

- Unsafe overrides with automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs). ISMP recommends overrides only be allow in emergent situations and made available in limited quantities.

Other common dispensing errors include:24

- Failure to review the patient history/record.

- Failure to check a drug against the label and the actual prescription.

- Failure to question the prescriber about unusual prescriptions/controlled substance prescriptions.

- Failure to review the prescription with a patient and monitor.

Best practices for preventing dispensing errors include having all medications in nonemergency situations reviewed by the pharmacist (in some cases, an advanced pharmacy technician under “tech-check-tech policies). The original medication order should be reviewed. Any questions about the medication, dosage or other information in the prescription should be clarified with the prescriber. If there is not a 24-hour pharmacy service, other possibilities to provide for pharmacy review should be explored, e.g. telepharmacy, remote review, or other qualified health professional review in the pharmacist’s absence. In this case, a process for pharmacist review retrospectively should be created and followed. A good resource to review is the ASHP Guidelines on Remoted Medication Order Processing.”39

Double-checks should be built into the medication management and workflow processes (e.g. keeping the original medication order, label, and medication container together throughout the dispensing process, using bar codes to scan the drug label against NDC ordered, scanning prescription label and checking contents against a visual picture of what the medication should look like, and having second data verification). When possible, commercially available medications should be used instead of compounding. Oral and parenteral medications should be dispensed in the most ready-to-administer form. Auxiliary labels should be used along with ensuring label readability to minimize issues after dispensing. Drug storage and organization in the pharmacy should minimize confusion among medications, with separation of high-risk medications, those with different routes of administration, and sound-alike and look-alike medications.

For ADCs, overrides should be minimized. The technology’s security function should be used and programmed to maximize medication security and lower the incidence of overrides. A process of monitoring overrides should be created and audits should be part of the quality improvement and risk reduction process. ISMP has added a new best practice related to ADCs with four points28:

- Limit the variety of medications that can be removed from an automated dispensing cabinet (ADC) using the override function.

- Require a medication order (e.g., electronic, written, telephone, verbal) prior to removing any medication from an ADC, including those removed using the override function.

- Monitor ADC overrides to verify appropriateness, transcription of orders, and documentation of administration.

- Periodically review for appropriateness the list of medications available using the override function.

Finally, it is important to address environmental factors that may contribute to dispensing errors, including ensuring adequate staffing levels and breaks, workload management (e.g. using pharmacy technicians, creating good workflow processes and stations, system support for prioritizing tasks), eliminating distractions in the dispensing process (e.g. phone, fax, radio, TV), ensuring adequate lighting/heat/humidity, reducing clutter and ensuring adequate space and proper storage of drugs (sound-alike, look-alike, route of administration). All of these environmental factors have been associated with medication errors.40

Administration

Several of ISMP’s top ten medication errors reported in 2019 are administration errors.38 These include unsafe practices associated with IV push medications, unsafe use of syringes for vinca alkaloids, wrong route (intraspinal injection) with tranexamic acid are among those reported.38 Use of bar-code scanning systems and independent double checks can prevent administration errors. In a recent study, one hospital was able to increase the use of barcode assisted medication administration (BCMA) scanning by 14% and pain reassessments an hour after opioid administration by 50% through a variety of tools, including 5-minute huddles and dashboards.41 Improvements were sustained nearly a year and a half after implementation. The number of adverse drug events related to administration errors fell 17%, estimated to save between $120,750 and $239,725 annually. Opioid-related adverse events also declined. There can be issues with BCMA, including wrong labeling vs using barcodes on the manufacturer’s container, silencing alerts, and manual entry vs scanning. Evaluating BCMA reports should be done regularly to assess compliance, ensure proper scanning and lead to other quality improvements related to the technology.

To address errors associated with accidental connection errors between different routes of administration (IV, enteral, intrathecal, etc.) the Global Enteral Device Supplier association is working with the International Standards Organization (ISO) to design new standards for medical device tubing. The goal is to design devices that do not allow connection between unrelated delivery systems. To help address inadvertent wrong routes errors due to device misconnections, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has developed new engineering standards (ISO 80369) that specifies the design of small-bore connectors to be unique for each clinical application. This ensures the connectors and tubing for each specific route will not fit into the connections for another clinical applications (e.g. neuraxial, IV, enteral).42 This standard has been incorporated into the ISMP best practices.28 ISMP recommends that all oral liquid medications that are not commercially available in unit dose packaging are dispensed by the pharmacy in an oral syringe or an enteral syringe that meets the ISO 80369 standard.

IV pump technology has also evolved to help reduce the potential for errors in IV medication administration. Smart pumps that incorporate medication libraries or guidelines that detect doses, concentrations and administration rates are an example. The medication safety team should develop standardized concentrations of IV medications to be used, setting upper/lower dosing limits, and use of hard and soft halts with the equipment.9 Comprehensive policies for the use of this technology should be developed and monitored as part of the safety plan. Educating all practitioners who are responsible for medication administration is important and should include how to properly identify a patient, learning the medication ordering, reviewing, preparing, dispensing and monitoring systems and policies, learning how to operate medication administration devices, including calculations, processes for high-alert medications and the quality improvement process. All training should be documented.9

Monitoring

Medication errors associated with monitoring span a range of issues from failing to monitor medication effects or inappropriate monitoring timing, to incorrect timing or transcription of serum concentration monitoring or lab values used to help with medication management.9 Examples include not checking a scheduled blood glucose level or failing to change medication orders in response to a value. Staff need to be trained to identify common medication adverse effects and have procedures in place to deal with these events. Medication monitoring includes assessing whether the medication is producing the desired therapeutic outcomes. Staff needs to be trained in the protocols for reacting to ineffective medication response. Multidisciplinary teams should be tasked with creating dosing algorithms, order sets and monitoring guidelines, usually under the approval of the pharmacy and therapeutics committee.9 An example is the ISMP best practice to eliminate the prescribing of fentanyl patches for opioid-naïve patients and/or patients with acute pain.28

Patient Discharge

Patients and caregivers should be aware of all aspects of patient care, including medication therapy. Healthcare providers can provide information to the patient and their caregivers about the prescribed medication they are receiving and what they are expected to do while they are in the hospital. Medication errors post discharge are a cause of avoidable hospital readmissions and are the most common post discharge adverse events.43 Pharmacists should be involved in medication reconciliation before discharge. Upon discharge, patients and their direct caregivers should be counseled about their medication which also provides an important double check in the medication use process and provides the patient with needed information to use the medication correctly. This includes discussing medications that were being taken prior to admission, during hospitalization and upon discharge, with added information about post-discharge medications and what medications are being discontinued. Education should include the drug’s name, purpose, appearance, dose, administration schedule, side effects and precautions. Ask the patient what questions they have and provide appropriate follow up. Patients should be encouraged to take an active role in their care, including always double checking their medications and calling their pharmacist if there is anything unusual, or if they have question. Use of transitional care programs in collaboration with community pharmacy providers can be an important tool in reducing avoidable medication-related readmissions.44 Successful programs share a number of key attributes that can be accessed through a helpful resource entitled, “ASHP-APhA Medication Management in Care Transitions Best Practices.”44

After discharge, providing patients with access to their medication profile can be helpful and encouraging them to keep an updated profile available to share with all their care providers. Up to 83% of dispensing errors can be discovered during patient counseling and corrected before the patient leaves the hospital. Counseling can also reinforce medication adherence and is an opportunity to enroll patients in programs that can support chronic care management, such as medication synchronization, auto refill, refill reminder and adherence packaging services, all of which support quality metrics used by numerous insurers. Using the three-question technique for new and refill medications developed by the Indian Health Service may be an efficient approach to providing counseling.45 See to Table 10.

| Table 10. Indian Health Service Three Prime Questions Technique for New and Refill Prescriptions45 |

| Questions New Prescriptions |

Content Provided |

| What did the prescriber tell you the medication was for? |

Name and purpose of the medication |

| How did the prescriber tell you to take the medication? |

Dose, route, frequency, storage, duration, and use techniques |

| What did the prescriber tell you to expect? |

Positive outcomes expected, what to do if they do not occur; possible side effects, how to decrease occurrence and actions to take if they do occur |

| Questions Refill Prescriptions |

Content Provided |

| What do you take this medication for? |

Purpose of the medication |

| How do you take it? |

Directions and techniques for use |

| What kind of problems are you having? |

Perceived side effects |

When Errors Occur

In spite of best efforts toward preventing medication errors, they do occur. How they are handled can determine the difference between professional complaints and litigation or successful error resolution with a satisfied patient. It is important than any error is handled promptly and professionally and follows the organization’s incident reporting policies and procedures. The most important goal is to ensure what is best for the patient and take action to reduce any harm. The error should be taken very seriously and with empathy. If the patient brings the error to your attention, it should be investigated immediately. Talk with the patient and find out why they think an error occurred, get the details of the situation – has the medication been taken, and if so, how much and how is the patient feeling? Find out what steps the patient has taken thus far and let them know you will be consulting with their prescriber and other healthcare providers as needed. Contact the patient’s prescriber and other healthcare providers, and caregivers, to ascertain whether interventions are needed and the best course of action. This may include facilitating delivery of a replacement medication as soon as possible, and/or referring the patient to urgent or emergency care. Organizations should have written procedures to follow in the event of an error and it is important to know what they are, how to access them and what further steps are to be taken, including other co-workers who should be notified.

Patients want to be heard and taken seriously. It is important to use active listening and express empathy with their complaints and concerns. Allow the patient to vent if necessary. Do not make excuses or appear otherwise dismissive, make evasive or flippant remarks or “talk down” to the patient. Acknowledge the fact an error may have occurred and give the patient assurances that the situation will be handled quickly and thoroughly. Provide the patient with information about the potential effect of the error as well as information gained from conversation with their prescriber. Providing patients with an explanation, if the source of the error is identified, may help alleviate their concern and also assures them that steps have been implemented so the error will not occur in the future. Follow your organization’s policies and procedures. A sincere apology about the concern, inconvenience and situation can go a long way to successful error resolution and patient satisfaction. Document all discussions with patients, parents/guardians, prescribing practitioners or other parties and ensure the documentation is in both the patient and pharmacy records.24

Like the patient, the pharmacy team members involved in the error may also be feeling fearful, scared and anxious. It is important to address “second victims” as part of the organization’s medication safety processes as well.

Evaluation and Error Reporting

Evaluating medication use systems and processes is a critical ongoing effort that should be undertaken by hospital organizations. These analyses focus on why an error occurred by collecting data about the error, identifying the root cause, creating recommendations to prevent an error from reoccurring and then implementing the recommendations. These include event detection and error reporting, root-cause analysis (RCA), and the organization’s quality improvement program.

The risk assessment methods discussed earlier can help identify potential areas where medication errors can occur. Event detection in these areas may come from a variety of processes, including:

- Voluntary error reporting,

- Observing a medication error

- Chart reviews

- Data mining and information technology (from a variety of sources, including smart pumps, ADCs, computers, etc.)

- Pharmacist interventions.

The use of data mining to analyze medication error reports has been an area of increased research interest. A recent analysis studied the use of machine learning methods to complete error report analysis.46 They found the method to save time and reduce clinician workload in analyzing reports for valuable information to incorporate into quality improvement efforts.46

RCA is a structured, retrospective approach to the investigation of safety-related incidents. The goal is to understand system issues that need to be addressed in order to prevent future errors. RCA is often used for very serious, sentinel events. A sentinel event is a patient safety event that results in death, permanent harm, or severe temporary harm.47 An action plan and a measurement strategy are outcomes of the RCA process which are used to address the root cause of the incident, which is required by the Joint Commission within 45 days of the event or its detection.9 Organizational learning and training needs are also identified, along with recommendations made to improve patient safety. Standard methods and templates should be adopted by the organization as well as policies when RCA will be used. There are a number of tools available from the Joint Commission and National Patient Safety Foundation (now part of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement) that can assist organization’s in designing their policies. 48,49

In addition to internal medication error data and review, data is available from voluntary national error reporting programs. These programs use the reports gathered to educate healthcare providers about error causes. The reports also allow stakeholders to develop strategies for preventing medication errors in the future. Investigating and using information about medication safety risks and errors that have occurred in other organizations and taking action to prevent similar errors is an ISMP best practice.28 Reporting errors to national programs is important in preventing future patient harm.

The ISMP operates the National Medication Errors Reporting Program (ISMP MERP).50 The ISMP MERP was established in 1975 and is a voluntary, practitioner-based medication error-reporting program. The program’s objectives are to:

- Learn the underlying causes of reported medication errors or hazards

- Disseminate valuable recommendations to organizations to prevent future errors

- Provide guidance to healthcare communities, regulatory agencies, and pharmaceutical and device manufacturers

Errors may be reported at: https://www.ismp.org/report-medication-error. There are two portals: one for healthcare practitioners and one for consumers. ISMP regularly analyzes reports and provides important information through its communication tools, including early warnings when new issues are identified.

The U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also has reporting programs and memorandum of understandings with ISMP and other organization to share publicly available information. MedWatch is the name of the FDA’s safety information and adverse event reporting program.51 Reporting may be completed online at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch/index.cfm. There are portals for both healthcare provider and consumers. The Agency encourages the following reports:

- “Unexpected side effects or adverse events can include everything from skin rashes to more serious complications.

- Product quality problems such as information if a product isn’t working properly or if it has a defect.

- Product Use/Medication Errors that can be prevented. These can be caused by various issues, including choosing the wrong product because of labels or packaging that look alike or have similar brand or generic names. Mistakes also can be caused by difficulty with a device due to hard-to-read controls or displays, which may cause you to record a test result that is not correct.

- Therapeutic failures. These problems can include when a medical product does not seem to work as well when you switch from one generic to another.”

The scope of the MedWatch program includes prescription and over-the-counter medicines, biologics, medical devices, combination products, nutritional products, cosmetics and food. Vaccine error reporting is done through separate systems: the ISMP’s National Vaccine Errors Reporting Program at https://www.ismp.org/report-medication-error and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) online at https://vaers.hhs.gov/reportevent.html.30,52

FDA MedWatch offers several ways to help you stay informed about the medical products you prescribe, administer, or dispense every day: e-mail (MedWatch E-list), Twitter, and RSS. You can subscribe here: https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch-fda-safety-information-and-adverse-event-reporting-program/subscribe-medwatch-safety-alerts.

Other quality improvement strategies include medication-use evaluation and failure mode and effects analysis (FEMA.) With medication-use evaluation, a specific medication, or process is studied with the goal to make improvements to processes, formularies, decision support systems, including CPOE, or any other medication support that can benefit from finding and incorporating best practices. A good resource is the “ASHP Guidelines on the Medication-Use Analysis.”53 FMEA is a structured, proactive method for prospectively evaluating a process to identify where and how it might fail and to assess the relative impacts of different failures. Where RCA is retrospective, FMEA is proactive. FMEA has been adapted by the VA to the healthcare setting and the Joint Commission has published a comprehensive resource for hospitals.54 The PowerPak CE library also has an excellent program that outlines details of both RCA and FMEA for medication error prevention, see: https://www.powerpak.com/course/content/117590.55

Summary

Medications can greatly improve health when used wisely and correctly. Medication errors do occur throughout the medication use system and cause preventable human suffering and financial cost. Using medications is not a risk-free activity. Significant efforts have been made during the past two decades to create systems that can be implemented to reduce the risk of medication errors. Understanding your responsibilities and following best practices to reduce medication errors can contribute to making medication use safe for your patients. Staying current on medication error trends through national organizations is an important part of that responsibility. Hospitals and health systems can implement a variety of strategies to assess medication error risk and make system improvements toward preventing medication errors, including providing education, training and support to clinicians. Improving patient safety requires a collaborative effort that integrates and makes it a priority throughout the organization.

REFERENCES

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MD, Ed. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine: Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. Available at: http://nap.edu/9728. Accessed November 1, 2020.

- Panagiot M, Khan K, Keers Rn, et.al. Prevalence, severity and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019:366-1418S. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4185 Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/366/bmj.l4185.full.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2020.

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors, Preventing Medication Errors. National Academies Press; 2007:124-25. Available at: http://nap.edu/11623. Accessed November 1, 2020.

- Medication use and spending in the U.S.: a review of 2018 and outlook to 2023. IQVIA Institute. May 2019. Available at: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/the-global-use-of-medicine-in-2019-and-outlook-to-2023. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- Flynn EA, Barker KN, Carnahan BJ. National observational study of prescription dispensing accuracy and safety in 50 pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):191-200. doi:10.1331/108658003321480731.

- Campbell PJ, Patel M, Martin JR, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community pharmacy error rates in the USA: 1993-2015. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(4):e000193. Published 2018 Oct 2. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000193

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

- Grissinger MG, Globus NJ, Fricker MP. The role of managed care pharmacy in reducing medication errors. JMCP 2003;9(1):62-65.

- Billstein-Leber M, Carrillo CJD, Cassano AT, Moline K, Robertson JJ. ASHP guidelines on preventing medication errors in hospitals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018 Oct 1;75(19):1493-1517.

- About medication errors. National Coordinating Council for Medication Error and Prevention website. Available at: https://www.nccmerp.org/about-medication-errors. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- Hayward RA, Asch SM, Hogan MM, Hofer TP, Kerr EA. Sins of omission: getting too little medical care may be the greatest threat to patient safety. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):686-691. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0152.x

- Key element of the medication-use system. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/ten-key-elements. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- ASHP statement of the role of the medication safety leader. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2019;77:308-312. Available at: https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/statements/role-of-medication-safety-leader.ashx. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- ISMP medication safety self-assessment® for high-alert medications. January 25, 2018. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/assessments/high-alert-medications. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- ASHP policy 1524: support for second victims. In: Hawkins B. ed. Best practices positions and guidance documents of ASHP. 2015-2016 ed. Bethesda, MD; American Society of Health System Pharmacists; 2015:212.

- CE for pharmacists: find your state’s requirements. July 1, 2020. University Learning Systems website. Available at: https://universitylearning.com/blog/medical-news/2020/07/01/ce-pharmacists-find-states-requirements/. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- Self-assessment. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/self-assessments. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- Resources. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/resources?field_resource_type_target_id%5B33%5D=33#resources--resources_list. Accessed November 12, 2020.

- FDA and ISMP lists of look-alike drug names with recommended tall man letters. 2016. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2017-11/tallmanletters.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- ISMP list of confused drug names. February 28, 2019. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/confused-drug-names-list?destination=/recommendations/confused-drug-names-list. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- ISMP list of high-alert medications in acute care settings. 2018. Institute for Safe Medication Practices Website. Available at: https://ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2018-10/highAlert2018new-Oct2018-v1.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- Frederico F. The five rights of medication administration. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/ImprovementStories/FiveRightsofMedicationAdministration.aspx#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20recommendations%20to,route%2C%20and%20the%20right%20time. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- The five rights: destination without a map. January 25, 2007. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/resources/five-rights-destination-without-map. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- Pharmacist liability claim report: 2nd edition. Identifying and addressing professional liability exposures. CAN/Health Professional Services Organization. 2019. Available at: http://www.hpso.com/Documents/Risk%20Education/individuals/Claim-Reports/Pharmacist/HPSO-CNA-Pharmacist-Claim-Report-2019.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Standardize 4 safety. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists website. Available at: https://www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-Practice/Standardize-4-Safety-Initiative?loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly. Accessed November 23, 2020.

- ISMP Medication safety alert: acute care. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://ismp.org/newsletters/acute-care. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP guidelines on managing drug product shortages in hospitals and health systems. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009; 66:1399-406.

- ISMP targeted medication safety best practices. February 21, 2020. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2020-02/2020-2021%20TMSBP-%20FINAL_1.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Machan C, Siebert U. The effect of electronic prescribing on medication errors and adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(5):585-600. doi:10.1197/jamia.M2667.

- Porterfield A, Engelbert K, Coustasse A. Electronic prescribing: improving the efficiency and accuracy of prescribing in the ambulatory care setting. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2014;11(Spring):1g. Published 2014 Apr 1.

- Radley DC, Wasserman MR, Olsho LE, Shoemaker SJ, Spranca MD, Bradshaw B. Reduction in medication errors in hospitals due to adoption of computerized provider order entry systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(3):470-476. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001241

- 2019 National progress report. 2019. Surescripts website. Available at: https://surescripts.com/docs/default-source/national-progress-reports/7398_ab-v2_2019-npr-brochure.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- Yang Y, Ward-Charlerie S, Dhavle A, et. al. Quality and variability of patient directions in electronic prescriptions in the ambulatory care setting. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018:24(7):691-699. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/full/10.18553/jmcp.2018.17404. Accessed November 24, 2020.

- Recommendations to reduce medication errors associated with verbal medication orders and prescriptions. May 1, 2015. National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention website. Available at: https://www.nccmerp.org/recommendations-reduce-medication-errors-associated-verbal-medication-orders-and-prescriptions. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Official “do not use” list. March 5, 2009. The Joint Commission website. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/deprecated-unorganized/imported-assets/tjc/system-folders/topics-library/dnu_listpdf.pdf?db=web&hash=6308831BDDB4BA3F046BB995E868DE2D. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP guidelines on compounding sterile preparations. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2014; 71:145-66.

- Admixing sterile injectables and infusions in patient care areas can lead to errors. November 11, 2020. Horsham, PA: Institute for Safe Medication Practices [press release.] Available at: https://ismp.org/news/admixing-sterile-injectables-and-infusions-patient-care-areas-can-lead-errors. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- ISMP publishes top 10 list of medication errors and hazards covered in newsletter. January 16, 2020. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/news/ismp-publishes-top-10-list-medication-errors-and-hazards-covered-newsletter. Accessed October 25, 2020.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP guidelines on remote medication order processing. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2010; 67:672-7.

- Flynn, E. A., Dorris, N. T., Holman, G. T., Camahan, B. J., & Barker, K. N. (2002). Medication dispensing errors in community pharmacies: a nationwide study. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 46(16), 1448–1451. https://doi.org/10.1177/154193120204601609.

- Ho J, Burger D. Improving medication safety practice at a community hospital: a focus on bar code medication scanning and pain reassessment. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(3):e000987.doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2020-000987.

- Andersen, Merissa. ISO 80369 compliant connectors help to reduce route of administration errors. October 27, 2020. Pharmacy Learning Network. Available at: https://www.managedhealthcareconnect.com/content/iso-80369-compliant-connectors-help-reduce-route-administration-errors. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Partnership for patients initiative. July 24, 2020. Available at:. partnershipforpatients.cms.gov. Accessed December 2,2020.

- ASHP-APhA medication management in care transitions best practices. February 2013. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists website. Available at: https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-centers/quality-improvement/learn-about-quality-improvement-medication-management-care-transitions.ashx. Accessed December 2, 2020.

- Lam N, Muravez SN, Boyce RW. A comparison of the Indian Health Service counseling technique with traditional, lecture-style counseling. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2015;55:503-510.

- Zhou S, Kang H, Yao B, Gong Y. Analyzing medication error reports in clinical settings: an automated pipeline approach. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:1611-1620. Published 2018 Dec 5.

- Sentinel event. Joint Commission website. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/. Accessed December 2, 2020.

- Joint Commission. Framework for conducting a root cause analysis and action plan (March 21, 2013). Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/rca_framework_101017.pdf?db=web&hash=B2B439317A20C3D1982F9FBB94E1724B. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement RCA2: improving root cause analyses and actions to prevent harm. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/RCA2-Improving-Root-Cause-Analyses-and-Actions-to-Prevent-Harm.aspx. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- Error reporting and analysis. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/error-reporting-programs. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- MedWatch: the FDA safety information and adverse event reporting program. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch-fda-safety-information-and-adverse-event-reporting-program. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- MedWatch online voluntary reporting form. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch/index.cfm. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP guidelines on medication-use evaluation. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1996; 53:1953-5.

- The Joint Commission. Failure Mode and Effects Analysis in Health Care: Proactive Risk Reduction. 3rd ed. 2010. http://www.jcrinc.com/assets/1/14/FMEA10_Sample_Pages.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 2018 Update: the utility of root cause analysis and failure mode and effects analysis in the hospital setting. 2018. PowerPak CE website. Available at: https://www.powerpak.com/course/content/117590. Accessed December 3, 2020.

Back to Top