Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Medication Safety: Preventing Medication Errors in Older Adults

Part 3 in a 4-part series on medication safety

Caring for seniors is perhaps the greatest responsibility we have. Those who have walked before us have given so much and made possible the life we all enjoy. – Senator John Hoeven

In the two decades since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released its landmark report, “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” providing recommendations for addressing medication errors, the focus on medication safety continues.1 The report recognized the pharmacist as “an essential resource” in medication safety because of the “immense variety and complexity of medications” available. Nowhere is this more evident than among older adults, those ≥65 years. The number of older adults is increasing. In the next decade, all the baby boomers will be ≥65 years, representing one in five people in the United States.2 Older adults will outnumber children for the first time in the United States.2

Medication-related adverse events are the most frequent safety incidents in this population.3 A recent analysis found older adults sought medical treatment or visited the emergency room more than 35 million times for adverse drug events (ADEs) between 2008 and 2018.4 These visits resulted in more than 2 million hospitalizations.4 Each day there are 750 older adults hospitalized due to serious side effects of one or more medications.4 While older adults comprise about 14% of the population, they account for 56% of U.S. hospitalizations for ADEs.5 Among the overall population, a recent meta-analysis of studies spanning from 2000 to 2019 suggest one in 20 patients are exposed to preventable harm in medical care with 25% of incidents being medication-related.6 In 2019, there were 5.96 billion prescriptions (30-day equivalent)7 filled in the United States which would result in an estimated 93,600,000 errors given a medication dispensing error rate of 1.57%.8,9

The burden of medication errors is high. Costs of treating drug-related injuries in hospitals are more than $3.5 billion a year,4,10 and the morbidity and mortality associated with medication errors is estimated to be $77 billion each year.11 Beyond economic costs, errors are costly in terms of patients’ loss of trust, reduced satisfaction and physical and psychological discomfort. They are costly as health professionals lose morale and frustration grows at providing less than the best care possible.12 Continued efforts to address medication error causes are critical to improve medication safety and public health. Pharmacists and the pharmacy team have important roles to play in preventing medication errors, especially among older adults.

What are Medication Errors?

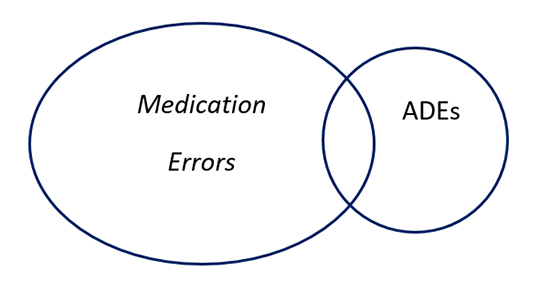

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error and Prevention (NCCMERP) defines a medication error as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing, order communication, product labeling, packaging, and nomenclature, compounding, dispensing, distribution, administration, education, monitoring, and use."12 Not all medication errors cause harm. When they do, they may be called ADEs, which are a subset of medication errors and are defined as “an injury resulting from medical intervention related to a drug.”1 See Figure 1.

Figure one: Relationship of ADEs and Medication Errors

ADEs

Errors may fall into several categories, including errors of omission, commission and system errors.13 Errors of omission are generally when something has not been done right, for example, failure to check patient allergies or provide counseling. Among older patients, these errors may include not having the correct information to use a medication or forgetting instructions. Errors of commission are when something has been done wrong, for example, dispensing the incorrect medication or providing the wrong dose or instructions, or if an older patient repeats a dose or stores their medication incorrectly. System errors are those not exclusively because of an individual’s action, for example environmental factors that distract pharmacy team members during the medication use process or having several people involved in a patient’s care without standardized information. See Table 1 for other examples of each.

| Table 1. Type of Errors13 |

| Definition |

Examples |

| Omission: an error resulting in an inappropriate increased risk of disease-related adverse event(s) resulting from receiving too little treatment (underuse). |

Errors of omission include problems such as not having the correct information to use a medication, confusing instructions, or forgetting a pharmacist’s instructions. |

| Commission: an error resulting in an inappropriate increased risk of iatrogenic adverse event(s) from receiving too much or hazardous treatment (overuse or misuse). |

Errors of commission include problems such as repeating a dose, doubts about using pill dispensers correctly, taking someone else’s medication, taking expired medications, storing medication inappropriately. |

| System Error: an error resulting from actions or factors that are part of a process, not just attributable exclusively to an individual’s actions alone. |

System errors include problems such as inadequate lighting, lack of double checks, not double-checking patient names/birthdays/medications against orders that result in errors. |

Medication errors can occur throughout the medication-use process. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) is a 501c (3) nonprofit organization devoted entirely to preventing medication errors. In the past 25 years, ISMP has provided tools and resources for healthcare professionals and consumers to help prevent errors. ISMP has defined “Key Elements of the Medication-Use System™14,” noting “Medication use is a complex process that comprises the sub-processes of medication prescribing, order processing, dispensing, administration, and effects monitoring.” Each component may be associated with medication errors as outlined in Table 2. Strategies for preventing these errors have been outlined in the first two parts of this medication safety continuing education series:

- Practical Approaches to Preventing Medication Errors in Community Pharmacy

- Practical Approaches to Preventing Medication Errors in Health System Pharmacy

| Table 2. ISMP’s Key Elements of the Medication-Use System |

| Element |

Error Potential |

| Patient information |

Failure to obtain patient’s demographic (age, weight) and clinical information (allergies) |

| Drug information |

Failure to provide accurate and useable drug information |

| Communication of drug information |

Miscommunication between prescriber, nurse and pharmacist |

| Drug labeling, packaging and nomenclature |

Look-alike, sound-alike names, confusing drug labeling and/or packaging |

| Drug storage, stock, standardization and distribution |

Poor shelf labels, not separating dosage forms on shelves, lack of standardized drug concentrations |

| Drug device acquisition, use and monitoring |

No safety assessments for drug delivery devices or independent double checks, not providing dosage tools/devices |

| Environmental factors |

Poor lighting, noise, interruptions, workload |

| Staff competency and education |

Not focusing on appropriate education, i.e. high-alert medications, policies and processes for medication safety |

| Patient education |

Failure to counsel on medication indications, doses, drug or food interactions, adverse effects, how to protect from errors |

| Quality processes and risk management |

Not analyzing medication error causes and having a system of detecting and preventing errors |

| This table has been adapted with permission from ISMP. https://www.ismp.org/ten-key-elements. |

This lesson’s focus is on understanding the reasons older adults may be prone to experiencing medication-related adverse events and strategies to help prevent them.

Factors Contributing to Medication-Related Problems in Older Adults

The primary factors that contribute to medication-related problems in older adults are physical and mental changes associated with aging, the presence of multiple morbidities and polypharmacy.3

With aging comes decreased functioning of all system organs, lowered homeostasis, and altered response to receptor stimulation. These physiologic changes impact both pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of medication.15 Absorption is affected by decreased gastric acid secretion and blood flow, delays in gastric emptying and longer intestinal transit time.15 These changes can delay the onset of action of oral medications although they may be fully absorbed. Aging skin is drier and less lipophilic which can reduce absorption of topical medications. Distribution is affected by decreased muscle mass and total body water and increased body fat.15 Metabolism is affected by decreased kidney and liver function which can cause medications to persist longer in the body and accumulate, requiring dose adjustments.15 Excretion is affected by lower kidney function, blood flow, creatinine clearance rate and glomerular filtration rate.15 Pharmacodynamic changes include receptor sensitivity and number, signal transduction and homeostatic mechanisms.15 These changes can put older adults at increased risk for treatment failure, adverse reactions, side effects and falls—the leading cause of fatal injuries in this population.16

Aging is often accompanied by impaired memory, vision and hearing. Older patients may have issues remembering when and how to take their medication correctly, what it is used for and what side effects to be concerned about. They may have difficulty reading written instructions or their medication labels and have trouble hearing instructions during counseling sessions. All these issues can lead older patients to improperly take their medications. In fact, between 75% and 96% of older adults acknowledge that they frequently make such mistakes.3

Older adults also have multiple morbidities and increased medication use that puts them at greater risk for experiencing medication-related adverse events. Eighty-five to 90% of older adults have at least one chronic illness, 60% have two or more, 33% have three or more, and 25% have four or more.17 The ten most common chronic conditions found in older adults are listed in Table 3.18 Many of these conditions require multiple medications to manage, leading to polypharmacy.

| Table 3: Most Common Chronic Conditions in Older Adults18 |

| Condition |

Percentage of Older Adults |

| Hypertension |

58% |

| Hyperlipidemia |

47% |

| Arthritis |

31% |

| Coronary heart disease |

29% |

| Diabetes |

27% |

| Chronic kidney disease |

18% |

| Heart failure |

14% |

| Depression |

14% |

| Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia |

11% |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

11% |

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy is most often defined in the literature as the use of multiple medications, usually five or more.19 The increase in polypharmacy is staggering. The number of U.S. adults taking five or more medications nearly doubled from 8.2% to 15% between 2000 and 2012.20 Forty-two percent of older adults take five or more medications daily.21 Eighteen percent take ten or more medications daily.21 Those numbers rise when vitamins, supplements and over-the-counter (OTC) medications are taken into account: then 67% of older adults take five or more drugs daily.21 Polypharmacy in and of itself, may not be harmful. If multiple medications are indicated and required to treat a patient and the benefits outweigh the risks, then polypharmacy is helpful. When a patient is taking multiple medications for which the harm outweighs the benefit, then polypharmacy can be harmful. The Lown Institute describes this situation as “medication overload,”22 in a report, entitled “Medication Overload: America’s Other Drug Problem.” Specific harms of medication overload include the following: 22

- ADEs: with each additional medication the risk of ADEs increases 7%-10%. The most common medications associated with adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and drug interactions in older adults include cardiovascular drugs, diuretics, anticoagulants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, and hypoglycemics.23 Anticoagulants, diabetes medications and opioids contribute to 60% of emergency room visits for ADRs.22

- Delirium: older patients taking six or more drugs in the hospital are twice as likely to experience delirium and those taking 10 or more drugs are nearly 2.5 times more likely than those taking five or less to experience impaired cognition. OTC antihistamines, H2 receptor antagonists, drugs with anticholinergic and/or sedative/hypnotic properties (opioids, benzodiazepines) and antipsychotic drugs can contribute to delirium and cognitive impairment.

- Falls: taking four or more drugs is associated with an 18% greater fall risk; taking 10 or more drugs is associated with a 50% greater fall risk.

- Mortality: among older adults, taking six to nine medications is associated with a 59% greater chance of mortality, taking 10 or more medication is associated with a 96% greater chance of mortality, compared to those taking no medications.

Polypharmacy is also associated with urinary incontinence and poor nutritional status in older adults.23 It can lead to diminished instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) because of functional decline caused by multiple medications. One study found 74% of patients with excessive polypharmacy (using > 10 drugs) to have difficulty with IADLs compared to 30% of patients with no polypharmacy.24 Polypharmacy can also lead to poor medication adherence. The number of medications is a stronger predictor of medication nonadherence than advancing age.25 Medication nonadherence can lead to other problems including disease progression, treatment failure, hospitalization and ADRs.

Drivers of medication overload cited by the Lown Institute include a culture of prescribing with an expectation of a “pill for every ill”, information and knowledge gaps among providers and patients, and a highly fragmented health care system.22 Contributors to the prescribing culture include direct-to-consumer drug advertising, medicalizing aging, fast-paced medical care, and the urge among prescribers to “do something” about medical conditions.22 Health care education and training may not include enough attention on appropriate prescribing and deprescribing, leading to knowledge gaps. Clinical practice guidelines often focus on adding medication rather than how to decrease medications. Even with more attention to value-based and team-based care in the past decade, patients may still receive care and prescriptions from many providers in different care settings with resulting challenges in coordination of care.

Optimizing Medication Use in Older Adults

Not addressing the medication overload issue and ADEs in older adults carries significant consequences. The Lown Institute estimates during the next decade that 74 million outpatient visits and 4.6 million hospitalizations will occur among older adults due to ADEs, at a cost of $62 billion and resulting in 150,000 deaths.22 Numerous strategies and tools can be implemented to optimize medication use in older adults. Broad-based recommendations in five categories were made in the Lown Institute’s follow up report, entitled “Eliminating Medication Overload: A National Action Plan, including:26

- Implementing prescription checkups;

- Raising awareness about medication overload;

- Improving information at the point-of-care;

- Educating and training health professionals in appropriate prescribing and deprescribing; and

- Reducing industry influence, especially their direct to consumer advertising (e.g., on television, the internet and in lay magazines).

Prescription checkups are target at older adults taking multiple medications and patients admitted to the hospital with an ADE or upon request, the report notes.26 They can occur in any health care setting, over multiple encounters, by a clinician or care team member and focus on preventing or relieving medication overload. The Institute recommends they be conducted at least annually and be coordinated by the patient’s primary care physician. During a prescription checkup, tools are used to identify potentially problematic medications. Then, medications are deprescribed based on the patient’s values, preferences and health goals.26

In addition to prescription checkups, other medication-related interventions outlined in the report include medication reconciliation, medication therapy management (MTM), and comprehensive medication management (CMM).26 These interventions are often implemented during care transitions and during medication monitoring. Other strategies may be used to prevent medication errors in older adults during various points in the medication use system, including:

- Patient demographic and clinical information

- Prescribing

- Order communication and transcribing

- Dispensing

- Administering

- Patient education

- Monitoring

Looking at which areas are more frequently associated with medication errors may help to prioritize strategy implementation. An analysis of 428 paid pharmacist liability claims between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2016 found the most common errors are associated with the wrong drug or dose.27 See Table 4 which compares the distribution of errors to a 2013 analysis which had 164 paid claims among 734 incidents during a 10-year period from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2011.27

| Table 4: Distribution of Liability Claim Errors27 |

| Claim Error |

Percentage of Occurrence |

| |

2018 |

2013 |

| Wrong drug |

36.8 |

43.8 |

| Wrong dose |

15.3 |

31.5 |

| Contamination of drug/container/equipment |

14.1 |

0.6 |

| Failure to consult with prescriber on question/concern |

5.5 |

4.9 |

| Prescription given to wrong patient |

5.5 |

3.1 |

| Compounding calculation and/or preparation error |

5.0 |

3.7 |

| Failure to obtain/review laboratory values required for proper dosing |

2.8 |

0.0 |

| Labeling error |

2.2 |

0.0 |

| Failure to provide instructions/wrong instructions |

1.7 |

0.0 |

| Failure to supervise |

1.7 |

0.0 |

Several categories saw declines in claims (wrong drug, wrong dose) while others posted gains; notably failure to consult prescribers, failure to review laboratory values needed for proper dosing, giving medication to the wrong patient, and failing to provide instructions or giving the wrong instructions. 27 These are all areas that are important to address vis-à-vis older adults. Consequences of these errors is significant and shown in Table 5. The top causes of death from errors include overdose (73.7%), infection (10.4%), exacerbation of illness (5.3%), glycemic event (5.3%) and loss of organ or organ function (5.3%).27

| Table 5: Severity and Cost Associated with Liability Claims27 |

| Error Outcome |

Percentage of Occurrence (%) |

Average Claim Cost Incurred ($) |

| Patient death |

11.3 |

$298,557 |

| Intervention to save patient’s life |

2.8 |

291,615 |

| Permanent patient harm |

17.4 |

274,873 |

| Error reached patient, no harm |

1.6 |

102,833 |

| Temporary patient harm requiring intervention/prolonged hospitalization |

41.3 |

72,577 |

| No medication error |

1.1 |

28,750 |

| Patient monitoring required to confirm no harm or intervention needed |

1.1 |

19,322 |

| Temporary patient harm requiring intervention |

23.4 |

10,387 |

A look at factors associated with the wrong drug dispensing liability claims reflect failures in one or more of the key elements of the medication use system (refer to Table 2.)27 These include:

- storage and quality process issues related to look-alike, sound-alike drugs;

- failure to consider patient history/medication profile/drug therapies;

- failure to review the prescription with the patient;

- failure to monitor and clarify anticoagulant dose or controlled substance prescriptions; and,

- failure to check with the prescriber.

Given what is known about older adults’ physical and cognitive changes, and problems with anticoagulants and opioids requiring hospitalization, addressing these factors is important in preventing medication issues in this population.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Information

Steps should be taken at every encounter to ensure a patient’s profile has all current demographic and clinical information, including the patient’s weight in the metric system, laboratory values, medical conditions, medications (prescription, OTCs and supplements) and immunizations. Having current lab values is especially important for older adults who may have compromised kidney and liver function. Making note of additional caregivers can help when changes occur to a patient’s regimen and new information needs to be given to the patient and their care team. The profile should also have the patient’s primary and specialty providers so questions can be directed to the appropriate clinician as well as any recommendations related to the patient’s medication regimen. Having accurate demographic and clinical information provides the baseline needed to evaluate any new prescription order(s) for the patient or when conducting a medication intervention (CMM, MTM, medication reconciliation.)

Prescribing Errors and Appropriate Prescribing

Prescribing errors contribute to medication errors and occur frequently among community-based primary care providers and in hospitals.28,29 One study analyzed 9,385 prescriptions in two states and found 28% to have errors, excluding those based on illegibility. Illegibility error rates were very high and inappropriate abbreviations, directions and dosage errors occurred frequently.28 The type of prescribing errors analyzed included:

- Illegibility

- Inappropriate abbreviation

- Directions

- Strength

- Dose

- Length of treatment

- Frequency

- Amount

Reviewers concluded that the “vast majority of errors could have been eliminated through the use of e-prescribing with clinical decision support.” E-prescribing has been shown to decrease prescribing errors, increases efficiency, decreases patient abandonment of prescriptions and helps to save on healthcare costs.30,31 While electronic prescribing has many benefits, errors within the process can still occur. The pharmacy team needs to be vigilant to carefully verify the patient’s information, drug, dosage, instructions, and physician, entering notes into the fill or patient records to clarify any issues with the order to ensure continuity of care with all pharmacy team members.

There will still be times when prescriptions are called in verbally, presented manually in written form or sent to the pharmacy via fax. There are strategies that the pharmacy team can employ to help reduce the possibility of errors, including reviewing each prescription to be sure It includes the patient name, age/weight if appropriate, drug name, dosage form, strength, dose frequency and route, indication, prescriber information and the person transmitting the order.32 Consider using templates or prescription pads containing all elements of ideal order. Always read back the prescription to the person giving the order when taking verbal orders. Transcribe the order neatly, print is preferable, using the metric system. Include leading zeros, used before a decimal quantity less than one, e.g. write 0.1 not .1. Trailing zeros should NOT be used after a decimal. e.g., write 1 not 1.0. Finally, do not use abbreviations when writing prescriptions. The Joint Commission has a list of abbreviations that should never be used, see Table 6.33

| Table 6. The Joint Commission Official “Do Not Use” List33 |

| Do Not Use |

Potential Problem |

Use Instead |

| U (unit) |

Mistaken for “0” (zero), the number “4” (four) or “cc” |

Write “unit” |

| IU (international unit) |

Mistaken for IV (intravenous) or the number 10 (ten) |

Write “international unit” |

| Q.D., QD, q.d., qd (daily) |

Mistaken for each other

Period after the Q mistaken for

"I" and the "O" mistaken for "I" |

Write “daily” |

| W.O.D., QOD, q.o.d., qod (every other day) |

Mistaken for each other

Period after the Q mistaken for

"I" and the "O" mistaken for "I" |

Write “every other day” |

Trailing zero (X.0 mg)

Lack of leading zero (.X mg) |

Decimal point is missed |

Write X mg

Write 0.X mg |

| MS |

Can mean morphine sulfate or

magnesium sulfate

Confused for one another |

Write “morphine sulfate” |

| MSO4 and MgSO4 |

Can mean morphine sulfate or

magnesium sulfate

Confused for one another |

Write “magnesium sulfate” |

| Additional Abbreviations for possible future inclusion |

| Do Not Use |

Potential Problem |

Use Instead |

>(greater than)

<(less than) |

Misinterpreted as the number

“7” (seven) or the letter “L”

Confused for one another |

Write “greater than”

Write “less than” |

| Abbreviations for drug names |

Misinterpreted due to similar

abbreviations for

multiple drugs |

Write drug names in full |

| Apothecary units |

Unfamiliar to many

practitioners

Confused with metric units |

Use metric units |

| @ |

Mistaken for the number

“2” (two) |

Write “at” |

| cc |

Mistaken for U (units) when

poorly written |

Write “mL” or “ml” or “milliliters” |

| µg |

Mistaken for mg (milligrams)

resulting in one thousand-fold

overdose |

Write “mcg” or “micrograms” |

Appropriate Prescribing

In older adults, it is especially important to be sure prescribed medication is appropriate, that the dosage has been adjusted based upon the patient’s kidney and liver function, that it will not cause interactions with the patient’s other medications and that the regimen makes sense and the patient can follow it.

During transitions of care, medication reconciliation is an important tool. During the reconciliation process all medications currently being taken by the patient are verified, with each drug reviewed for appropriateness for the situation/setting, reconciling the new drug list with the previous list with all changes and reasons for changes documented and communicating the updated list to the next care provider.34 The Structured History of Medication Use (SHiM) is a validated tool designed to assist pharmacists and other providers to carry out medication reconciliation in a structured way. Use of the SHiM has shown it highlights medication discrepancies with potential clinical relevance in about 20% of older adults.35

There are a number of prescribing assessment tools specific to older adults, including, but not limited to, the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI)36, the AGS Beers Criteria37 and Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert Doctors to Right Treatment (STOPP/START) criteria.38 The MAI addresses ten aspects of a prescription outlined in Table 7. Many of the MAI questions are asked as part of CMM and MTM interventions that utilize the medication indication, effectiveness, safety and adherence pharmaceutical care process.

| Table 7. Medication Appropriateness Index36 |

| 1 |

Is there an indication for the drug? |

| 2 |

Is the medication effective for the condition? |

| 3 |

Is the dosage correct? |

| 4 |

Are the directions correct? |

| 5 |

Are the directions practical? |

| 6 |

Are there clinically significant drug–drug interactions? |

| 7 |

Are there clinically significant drug–disease interactions? |

| 8 |

Is there unnecessary duplication with other drugs? |

| 9 |

Is the duration of therapy appropriate? |

| 10 |

Is this drug the least expensive alternative compared to others of equal utility? |

The American Geriatric Society’s (AGS) Beers Criteria were first developed by Dr. Mark H. Beers in 1991 to decrease inappropriate prescribing and ADEs and to identify medications or therapeutic classes that should be avoided in older adults in nursing homes.37 The AGS now oversees revisions to the criteria, providing updates every three years. The criteria include potentially inappropriate medications in older adults, drug–drug, drug–disease and drug–syndrome interactions in older adults, medications to avoid or reduce dose based on kidney function, and medications to use with caution.37 The lists are meant to be used as a tool for medication reviews and improve the care for older patients.

The STOPP/START criteria were first published in 2008 and arose out of perceived deficiencies in the AGS Beers Criteria. STOPP criteria are designed to detect common and preventable potentially inappropriate medications while the START criteria are focused on potential medication omissions. The second version of STOPP/START have 114 criteria: 80 STOPP and 34 START. Criteria are organized into categories primarily based upon physiological systems:

- Cardiovascular system

- Central nervous system

- Gastro‐intestinal system

- Musculoskeletal system

- Respiratory system

- Urogenital system

- Endocrine system

- Drugs that adversely affect fallers

- Analgesics

- Duplicate drug classes

Examples of STOPP/START criteria are listed in Table 8.39

Table 8. Examples of STOPP/START Criteria39 |

| Criteria Type |

STOPP |

START |

| Cardiovascular System |

Thiazide diuretic with gout history |

Warfarin in presence of chronic atrial fibrillation |

| Digoxin at long-term dose with impaired renal function |

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) following acute myocardial infarction |

| Central Nervous System |

Prolonged use of 1st generation antihistamines (>1 week) |

Antidepressant in presence of moderate-sever depressive symptoms lasting at lease 3 months |

| GI System |

PPI for peptic ulcer disease at full therapeutic dosage for >8 weeks |

PPI for severe acid reflux disease or peptic stricture requiring dilatation |

These criteria have been studied in a number of clinical trials to have clinical benefit, although the trials were smaller scale, single-center, single-blind.38 Authors of the second version note, “STOPP/START criteria as an intervention applied within 72 h of admission significantly reduce ADRs (with an absolute risk reduction of 9.3%; number needed to treat = 11) and average length of stay by 3 days in older people hospitalised with unselected acute illnesses.”38

Patients should be encouraged to routinely ask each of their medical providers if the medication they are taking is still necessary to continue, or can it be discontinued, or could the dose be tapered down. Whenever any new drug is prescribed, older adults should ask how long the medication will be used, or what the endpoint is for taking a medication. Older patients should always ask their doctor if they are open to deprescribing a drug that may potentially be unnecessary.

Dispensing and Administration

A primary contributor to wrong drug errors is failure to take special precautions with sound-alike and look-alike drugs (15.1%).27 These medications should be separated on pharmacy shelves using color or tall man letters. The ISMP maintains a list of look-alike drug names with tall man letters.40 Examples of the list may be found in Table 9.

| Table 9. Examples of Look-Alike Drug Names with Tall Man Letters |

| Drug Name with Tall Man Letters |

Confused With |

| amLODIPine |

aMILoride |

| CeleBREX |

CeleXA |

| FLUoxetine |

DULoxetine – PARoxetine |

| glyBURIDE |

glipiZIDE |

| HumuLIN |

HumaLOG |

| hydroCHLOROthiazide |

hydrOXYzine – hydrALAZINE |

| oxyMORphone |

HYDROmorphone – oxyCODONE – OxyCONTIN |

| prednisoLONE |

predniSONE |

| risperiDONE |

rOPINIRole |

| traMADol |

traZODone |

| This table has been adapted with permission from ISMP. https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2017-11/tallmanletters.pdf |

Among older adults, examples of paid claims involving wrong drug/wrong dose include27:

- Methotrexate prescribed for rheumatoid arthritis with normal dose for the patient of 25 mg every seven days but it was dispensed as 25 mg every day resulting in an overdose and toxicity causing permanent brain damage.

- Coumadin 5 mg dispensed instead of 1 mg resulting in bleeding and hospitalization with vitamin k treatment.

- Digoxin prescribed 0.125 mg once a day dispensed as 0.25 mg twice a day resulting in toxicity and death.

These errors involved high-alert medications. High-alert medications are drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when they are used in error.41 ISMP maintains lists of high-alert medications for both the community/ambulatory and acute care settings. An example of these medication classes in the community and ambulatory care settings commonly used by older adults includes41:

- Anticoagulants (e.g. warfarin, heparin, new direct acting oral anticoagulants)

- Insulins and oral hypoglycemic agents

- Opioids

High-alert medications should be flagged with additional care taken to ensure the correct medication has been selected with the correct dosage. ISMP suggests using auxiliary labels, shelf labels and automated alerts and standardizing the storage, dispensing and administration of these products.41

When it comes to medication administration, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement recommends utilizing the “five rights” to reduce medication errors and harm, these rights are: the right patient, the right drug, the right dose, the right route, and the right time.42 Double-checks should be built into the workflow systems and the patient bedside for medication administration including the use bar code scanning technology. Appropriate dosing devices should be dispensing with all medications that use the metric system. It is important to address environmental factors that may contribute to dispensing errors. See the other two continuing education lessons in this series for more detailed recommendations.

Patient Education and Monitoring

Patient education is an important double check in the medication use process and gives the patient needed information to use the medication correctly. Before beginning a counseling session with an older patient, identify any potential barriers, such as literacy issues, vision, hearing or speech problems, stigmas, or any other concerns. The counseling should be adjusted as different barriers are discovered. Review the drug’s name, purpose, appearance, dose, administration schedule, side effects and precautions and provide written instructions to both the patient and their caregivers. If a different manufacturer is used and the medication’s size, shape and/or color has changed, it is important to bring this to the patient’s attention.

Ask the patient what questions they have and provide appropriate follow up. Using the teach-back method and have the patient repeat what the medication is for, how they will take it, what side effects to look for and what to do if they miss a dose. Using the three-question technique for new and refill medications developed by the Indian Health Service may be an efficient approach to providing counseling.43 See to Table 10.

| Table 10. Indian Health Service Three Prime Questions Technique for New and Refill Prescriptions43 |

| Questions New Prescriptions |

Content Provided |

| What did the prescriber tell you the medication was for? |

Name and purpose of the medication |

| How did the prescriber tell you to take the medication? |

Dose, route, frequency, storage, duration, and use techniques |

| What did the prescriber tell you to expect? |

Positive outcomes expected, what to do if they do not occur; possible side effects, how to decrease occurrence and actions to take if they do occur |

| Questions Refill Prescriptions |

Content Provided |

| What do you take this medication for? |

Purpose of the medication |

| How do you take it? |

Directions and techniques for use |

| What kind of problems are you having? |

Perceived side effects |

Older patients should be encouraged to always double check their medications and call their pharmacist if there is anything unusual. Providing patients with access to their medication profile can be helpful. Encourage older patients to keep a current medication list to share with all their care providers. Encourage all older adults to maintain annual wellness visits with their primary care provider. These wellness visits provide a great opportunity to review all medications. Older patients with more complex medical disorders may benefit from seeing a physician board-certified in Geriatric Medicine who can then function as the patient’s primary care provider. During these visits, patients should routinely ask each of their providers if the medication they are taking is still necessary to continue, or can it be discontinued or the dose tapered.

Counseling can also reinforce medication adherence. Older patients may have issues with complicated medication schedules, costs, side effects or other problems that impact adherence. There are a number of tools that can help older patients. Compliance packaging and pill dispensers, both manual and electronic, may help older patients organize medications to fit their daily routine. Medication synchronization, automated refills and refill reminder services can support adherence, one of many quality metrics used by numerous insurers.

Medication monitoring can occur with each encounter. Ask the patient if they are experiencing any issues and follow up as needed. More formal care process approaches include CMM and MTM. CMM is a patient-centered approach focused on optimizing medication use and improving health outcomes delivered by a pharmacist working in collaboration with the patient and other care providers.44 This care process ensures each patient’s medications are individually assessed to determine that each medication has an appropriate indication, is effective for the medical condition and achieving defined patient and/or clinical goals, is safe given the comorbidities and other medications being taken, and that the patient is able to take the medication as intended and adhere to the prescribed regimen.44

MTM, on the other hand, grew out of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 and is targeted to Medicare beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions, taking multiple medications and likely to incur annual medication costs exceeding a certain level.26 There is no standard definition of MTM, but services often include an annual comprehensive medication review, creating a medication action plan and providing a personalized medication list. Many organizations and insurers beyond Medicare Part D providers have adopted some form of MTM services.45 Older patients may be eligible for MTM services based on their health care coverage and it is important for the pharmacy team to identify patients who could benefit from these services and get them scheduled to receive them.

Older adults should be encouraged to consult with their pharmacist to do a complete medication review, including all OTC drugs and supplements. While the pharmacist may not always have access to a patient’s medical record, they still may be able to identify high-risk drugs, or drug-drug, or drug-food interactions. By considering a patient’s medical and medication history, a pharmacist may identify drugs appropriate for deprescribing, and with a patient’s permission, may consult with the appropriate medical provider to discuss recommendations to avoid adverse drug events.

Resources for Older Patients

There are many resources geared to older patients designed to help them use their medications correctly and to report medication-related issues. The pharmacist and pharmacy team members should be familiar with these resources and recommend them to older patients when appropriate.

The ISMP operates the ConsumerMedSafety website (https://consumermedsafety.org/). The website has medication safety articles on a variety of topics such as receiving a prescription and safe storage and disposal. Consumers can sign up for complimentary newsletters and access tips and tools for taking medications safely. They can also see FDA safety alerts and report any problems or medication errors to the ISMP’s National Medication Errors Reporting Program (ISMP MERP).46 The ISMP MERP was established in 1975 and is a voluntary medication error-reporting program (https://www.ismp.org/report-medication-error). The program’s objectives are to:

- Learn the underlying causes of reported medication errors or hazards

- Disseminate valuable recommendations to organizations to prevent future errors

- Provide guidance to healthcare community, regulatory agencies, and pharmaceutical and device manufacturers

The National Council on Patient Information (NCPIE) launched BeMedWise.org in 2017 (www.bemedwise.org). NCPIE is one of the original patient safety coalitions. The website is a tool for consumers, patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals alike. One section is designed for older adults that has tips for using medications safely (https://www.bemedwise.org/medication-management-for-older-adults/).

The FDA also has a guide for older adults at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-you-drugs/medicines-and-you-guide-older-adults#senior that provides useful tips for using medications safely and working with physicians, pharmacists and other providers and caregivers to achieve the best health outcomes. A concise resource with 4 medication safety tips is available at: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/4-medication-safety-tips-older-adults.

Summary

Everyone on the pharmacy team has a role to play in preventing medication errors, especially among older patients. Older adults experience more ADRs than other patients because of the physical and mental changes associated with aging, multiple morbidities and medications used to manage them. Medications can greatly improve health when used wisely and correctly, but medication overload can lead to serious problems. Medication errors do occur and cause preventable human suffering and financial cost. There are a number of strategies and tools that can help the pharmacist and pharmacy team members prevent medication errors in older patients and optimize their medication therapy. Being aware of issues facing older adults and following best practices to reduce medication errors can contribute to making medication use safe for your patients.

References

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MD, Ed. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine: Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. Available at: http://nap.edu/9728. Accessed December 9, 2020.

- Older people projected to outnumber children for first time in U.S. history [press release.] U.S. Census Bureau. October 8, 2019. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/cb18-41-population-projections.html#:~:text=By%202030%2C%20all%20baby%20boomers%20will%20be%20older%20than%20age%2065.&text=%E2%80%9CBy%202034%20(previously%202035),decade%20for%20the%20U.S.%20population. Accessed December 9, 2020.

- Mira JJ. Medication errors in the older people population. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2019;12(6):491-494.

- Lown Institute. Medication overload: America’s other drug problem. April 1, 2019. Available at: https://lowninstitute.org/reports/medication-overload-americas-other-drug-problem/. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, Geller A. US emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events, 2013-2014. JAMA 2016; 316(20): 2115-2125.

- Panagiot M, Khan K, Keers Rn, et.al. Prevalence, severity and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019:366-1418S. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/366/bmj.l4185.full.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Medication use and spending in the U.S.: a review of 2018 and outlook to 2023. IQVIA Institute. May 2019. Available at: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/the-global-use-of-medicine-in-2019-and-outlook-to-2023. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Flynn EA, Barker KN, Carnahan BJ. National observational study of prescription dispensing accuracy and safety in 50 pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):191-200.

- Campbell PJ, Patel M, Martin JR, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community pharmacy error rates in the USA: 1993-2015. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(4):e000193.

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors, Preventing Medication Errors. National Academies Press; 2007:124-25. Available at: http://nap.edu/11623. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Grissinger MG, Globus NJ, Fricker MP. The role of managed care pharmacy in reducing medication errors. JMCP 2003;9(1):62-65.

- About medication errors. National Coordinating Council for Medication Error and Prevention website. Available at: https://www.nccmerp.org/about-medication-errors. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Hayward RA, Asch SM, Hogan MM, Hofer TP, Kerr EA. Sins of omission: getting too little medical care may be the greatest threat to patient safety. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):686-691.

- Key element of the medication-use system. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/ten-key-elements. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Trifirò G, Spina E. Age-related changes in pharmacodynamics: focus on drugs acting on central nervous and cardiovascular systems. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12(7):611-620.

- Keep on your feet—preventing older adult falls. December 9, 2020. Center for Disease Control website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/older-adult-falls/index.html#:~:text=Every%20second%20of%20every%20day,particularly%20among%20the%20aging%20population. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- Schraeder C, Dworak D, Stoll JF, et al. Managing elders with comorbidities. J Ambul Care Manage. 2005;28(3):201-209.

- The Healthy Aging Team. Top 10 chronic conditions in adults 65+ and what you can do to prevent or manage them. February 2, 2017. National Council on Aging website. Available at: https://www.ncoa.org/blog/10-common-chronic-diseases-prevention-tips/. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC geriatrics 2017; 17(1): 230.

- Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA 2015;314(17): 1818-1831.

- Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, Gillet V, Alexander GC. Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176(4): 473-482.

- Garber, J., and Brownlee, S. Medication overload: America’s other drug problem. Brookline, MA: The Lown Institute. April 2019. Available at: https://doi.org/10.46241/LI.WOUK3548. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):173-186.

- Jyrkka J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, et al. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;20:514-522.

- Colley CA, Lucas LM. Polypharmacy: the cure becomes the disease. J Gen Int Med. 1993;8:278-283.

- Eliminating medication overload: A national action plan. Working Group on Medication Overload. Brookline, MA: The Lown Institute, 2020. Available at: https://doi.org/10.46241/LI.YLBW4885. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Pharmacist liability claim report: 2nd edition. Identifying and addressing professional liability exposures. CAN/Health Professional Services Organization. 2019. Available at: http://www.hpso.com/Documents/Risk%20Education/individuals/Claim-Reports/Pharmacist/HPSO-CNA-Pharmacist-Claim-Report-2019.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2020.

- Abramson EK, Bates DW, Jenter C, et al. Ambulatory prescribing errors among community-based providers in two states. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:644-648.

- Bobb A, Gleason K, Husch M, Feinglass J, Yarnold PR, Noskin GA. The epidemiology of prescribing errors: the potential impact of computerized prescriber order entry. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Apr 12;164(7):785-792.

- Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Machan C, Siebert U. The effect of electronic prescribing on medication errors and adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(5):585-600.

- Porterfield A, Engelbert K, Coustasse A. Electronic prescribing: improving the efficiency and accuracy of prescribing in the ambulatory care setting. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2014;11(Spring):1g.

- Recommendations to reduce medication errors associated with verbal medication orders and prescriptions. May 1, 2015. National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention website. Available at: https://www.nccmerp.org/recommendations-reduce-medication-errors-associated-verbal-medication-orders-and-prescriptions. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Official “do not use” list. March 5, 2009. The Joint Commission website. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/deprecated-unorganized/imported-assets/tjc/system-folders/topics-library/dnu_listpdf.pdf?db=web&hash=6308831BDDB4BA3F046BB995E868DE2D. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Lavan AH, Gallagher PF, O'Mahony D. Methods to reduce prescribing errors in elderly patients with multimorbidity. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:857-866.

- Drenth-van Maanen AC, Spee J, van Hensbergen L, Jansen PA, Egberts TC, van Marum RJ. Structured history taking of medication use reveals iatrogenic harm due to discrepancies in medication histories in hospital and pharmacy records. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(10):1976–1977.

- Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(10):1045–1051.

- By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

- O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–218.

- Ryan C. The basics of the STOPP/START criteria. Available at: https://www.pcne.org/upload/ms2011d/Presentations/Ryan%20pres.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- FDA and ISMP lists of look-alike drug names with recommended tall man letters. 2016. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2017-11/tallmanletters.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- ISMP list of high-alert medications in community/ambulatory healthcare. 2011. Institute for Safe Medication Practices Website. Available at: https://forms.ismp.org/communityRx/tools/highAlert-community.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- Frederico F. The five rights of medication administration. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/ImprovementStories/FiveRightsofMedicationAdministration.aspx#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20recommendations%20to,route%2C%20and%20the%20right%20time. Accessed January 6, 2021.

- Lam N, Muravez SN, Boyce RW. A comparison of the Indian Health Service counseling technique with traditional, lecture-style counseling. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2015;55:503-510.

- The Patient Care Process for Delivering Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM): Optimizing Medication Use in Patient-Centered, Team-Based Care Settings. CMM in Primary Care Research Team. July 2018. Available at http://www.accp.com/cmm_care_process. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- American Pharmacists Association. APhA pharmacist patient care services digest 2015. Available at: https://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/Pharmacists%20Patient%20Care%20Services%20Digest%202015.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Error reporting and analysis. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. Available at: https://www.ismp.org/error-reporting-programs. Accessed December 17, 2020.

Back to Top