Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Adult Pneumococcal Immunization Recommendations and the Role of Pharmacists

INTRODUCTION

With all of the attention paid to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection over the past several years, it is easy to neglect other vaccine preventable infections, such as influenza and pneumonia. Still, pneumococcal pneumonia accounts for approximately 5,000 deaths annually.1 While this number may not capture headlines, it remains a frustratingly high given that 4 highly efficacious vaccines are available in the United States to help improve the clinical course of this infection. This program will discuss the background on pneumococcal infection, provide detail on the available vaccines used for disease prevention, highlight the most up-to-date guideline recommendations, and examine ways to improve vaccine uptake, including strategies to help patients overcome vaccine hesitancy.

BACKGROUND

Pathophysiology

Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs that may be caused by bacterial, viral (eg, COVID-19), or fungal causes.2,3 The most common bacterial pathogens responsible for pneumococcal infection include Pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, group A Streptococcus, and other aerobic and anaerobic gram-negative organisms. Less common or “atypical” bacterial causes include Legionella, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia. Pneumococcal pneumonia is the most common type of pneumonia and is caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae infiltration.4

S pneumoniae colonizes the upper respiratory tract as part of the normal flora of up to 90% of healthy individuals. As many as 100 serotypes of S pneumoniae have been identified, most of which are expected to cause serious disease. However, previous to the widespread use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, 7 common serotypes were responsible for about 50% of invasive pneumococcal disease.5

S pneumoniae can be spread by respiratory droplets and may be spread by asymptomatic carriers. It is a notable cause of illness in both adults and children. It is not only the most common cause of pneumonia, but certain serotypes may also cause sinusitis, otitis media, meningitis, and bacteremia.5

The proportion of community-acquired pneumonias (CAP) caused by S pneumoniae has dropped secondary to the introduction of vaccines and antibiotics, but this bacterium still accounts for approximately 15% of pneumonia cases in the US and 27% worldwide.6 CAP is a category of pneumonia in which the infection is acquired outside of a hospital, while hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) occurs after at least 48 hours of hospitalization. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a subset of HAP that affects patients receiving mechanical ventilation. S pneumoniae causes between 9% to 46% of HAP and VAP cases, while this bacterium is the primary cause of CAP.7-9 Health care–associated pneumonia is a historic designation that is no longer recognized by updated pneumonia treatment guidelines after the determination that these patients are not at an increased risk of multidrug-resistant pathogens.9,10

Epidemiology/Etiology

On the whole, pneumonia causes approximately 1.5 million emergency room visits annually in the US.5,11 In 2020, pneumonia led to more than 47,000 deaths.11 Specifically, there are approximately 320,000 cases of pneumococcal pneumonia each year, which lead to 150,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths.1 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, pneumonia and influenza together represented the most common cause of the death related to infectious disease and the seventh most common cause of death overall in the US.12

Pneumococcal pneumonia has a brief incubation period of 1 to 3 days with a relatively quick onset of symptoms including fever, shaking, chills, productive cough, pleuritic chest pain, malaise, weakness, and difficulty breathing.5 Other pneumococcal infections, including bacteremia and meningitis, may occur despite the presence or absence of pneumonia and are collectively referred to as invasive pneumococcal disease. Invasive pneumococcal disease had an incidence of 8 per 100,000 people in 2019.13

A variety of patient populations are at an increased risk of developing serious complications from pneumococcal infection, including anyone over the age of 65 years, those with alcoholism; chronic heart, lung, kidney, or liver disease; diabetes; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; cancer; nephrotic syndrome; or sickle cell disease, a damaged spleen, or no spleen.14 Individuals are also at risk if they have a cochlear implant or a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, or if they are a solid organ transplant recipient or are immunocompromised. Cigarette smokers are also at an increased risk of complications.14

Pneumococcal pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease are mostly vaccine preventable. Since the first introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine, the rate of pneumococcal pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease has dropped dramatically.13,15 This represents an extraordinary opportunity for pharmacists to intervene with vaccination guidance for patients.

PNEUMOCOCCAL VACCINES

To date, 4 vaccines have received approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of pneumococcal disease caused by S pneumoniae. These include 1 pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV) and 3 pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs).

The immune response to a pure polysaccharide vaccine, such as the PPSV, involves stimulation of B cells without the assistance of helper T cells. This response does not trigger production of memory B and T cells. Antibodies induced by polysaccharide vaccines have less functional activity than those induced by protein antigens. The immune systems of children are too immature to produce an effective immune response to a non-protein-based antigen; therefore, polysaccharide vaccines offer inconsistent protection to children younger than 2 years of age.16

Conjugate vaccines, on the other hand, are protein-based and effectively produce an immune response in infants. These vaccines can also boost antibody responses on repeat vaccination, unlike polysaccharide vaccines. Conjugate vaccines involve combining (or “conjugating”) polysaccharides with proteins to elicit a protein-based immune response.16 Conjugation is used for all of the available PCVs, in which a polysaccharide is linked to a diphtheria protein carrier, specifically diphtheria cross-reacting material 197 (CRM197) protein.17-19

There is also an adjuvant (aluminum) included in each of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, which is included to produce a better immune response.17-19 Aluminum gels or aluminum salts represent the gold standard for vaccine adjuvants.20 The effectiveness of incorporating adjuvants into vaccines stems from their ability to stimulate an inflammatory response, which strengthens the response to the antigen.20,21 This inflammatory response can unfortunately also increase adverse events including injection site reactions, such as pain and swelling, and systemic reactions, including flu-like symptoms.21

PPSV23

In 1977, the first pneumococcal vaccine was licensed. The vaccine consisted of purified capsular polysaccharide antigen from 14 types of pneumococcal bacteria.5 In 1983, a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) under the brand name Pneumovax 23 was licensed to replace the 14-valent vaccine.22 This vaccine contains polysaccharides from 23 strains of S pneumonia, which cause 60% to 70% of invasive pneumococcal disease (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F, and 33F; see TABLE 1).5,23

Among healthy adults who are immunized with PPSV23, greater than 80% will develop antibodies within 2 to 3 weeks after vaccination.5 Although vaccine efficacy declines with advancing age and may be less effective in patients with underlying illness, the vaccine can still provide protection for these high-risk patients and should be administered.5

PPSV23 has been proven to reduce the risk of invasive disease caused by the serotypes included in the vaccine by 60% to 70%.5 Although results from studies have shown PPSV23 does not reduce the incidence of pneumococcal pneumonia, researchers have concluded that vaccination with PPSV23 can improve outcomes in patients with pneumococcal pneumonia including a decreased need for admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and reduced mortality.24

PPSV23 is available as a single-dose vial or prefilled syringe that should be stored upon receipt in the refrigerator between 2°C to 8°C (36°F to 46°F). The full contents of the vial or prefilled syringe (0.5 mL) should be administered either subcutaneously or intramuscularly in the deltoid muscle or lateral mid-thigh.23

| TABLE 1. Vaccination Coverage of Pneumococcal Serotypes5,23 |

|

Vaccine

|

Serotype

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6A

|

6B

|

7F

|

8

|

9N

|

9V

|

10A

|

|

PPSV23

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

PCV13

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

PCV15

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

PCV20

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

Vaccine

|

11A

|

12F

|

14

|

15B

|

17F

|

18C

|

19A

|

19F

|

20

|

22F

|

23F

|

33F

|

|

PPSV23

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

PCV13

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

PCV15

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

PCV20

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Abbreviations: PCV, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PPSV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

|

Conjugate Vaccines

Since PPSV23 was approved, 3 PCVs have been approved, including 2 in 2021. These include pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV13 under the trade name Prevnar 13), PCV20 (Prevnar 20), and PCV15 (Vaxneuvance).15

PCV13

PPSV23 remained the only pneumococcal vaccine on the market until 2000 when the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) became available.5 The uptake of this vaccine resulted in a decrease in pneumococcal disease in all ages, but most notably, a 99% decrease in invasive disease caused by the serotypes covered by this vaccine. In 2010, the FDA approved PCV13 (Prevnar-13), which replaced PCV7. PCV13 added an additional 6 serotypes to those in PCV7 to provide improved coverage against invasive pneumococcal disease.5

PCV13 contains 13 serotypes of S pneumoniae (1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, and 23F; see TABLE 1) and is indicated for use in adults for the prevention of pneumonia and invasive disease caused by the S pneumoniae serotypes covered by the vaccine.17 Additionally, this vaccine is approved for use in children 6 weeks through 17 years of age for the prevention of invasive disease caused by the 13 serotypes in the vaccine and for children 6 weeks through 5 years of age for the prevention of otitis media caused by 7 of the 13 serotypes in the vaccine (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F).17

PCV13 is available as a single-dose prefilled syringe. Like PPSV23, it should be stored upon receipt in the refrigerator between 2°C to 8°C (36°F to 46°F); however, it is stable when stored for up to 4 days at temperatures up to 25°C (77°F).17 Immediately before administration, the syringe should be shaken vigorously to obtain a homogenous, white suspension since the solution contains an adjuvant. The full contents should then be administered intramuscularly in the deltoid muscle for all patients except infants, where the preferred site of administration is the anterolateral portion of the thigh.17

PCV20

In June 2021, the FDA approved PCV20 (Prevnar-20), which covers all 13 serotypes of S pneumoniae covered by PCV13, with additional coverage for serotypes 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, 15B, 22F, and 33F.19 These additional 7 serotypes are estimated to account for approximately 30% of all invasive pneumococcal disease.25

PCV20 is FDA-approved for the prevention of pneumonia and invasive disease caused by S pneumoniae caused by the 20 serotypes listed above in adults 18 years of age and older.19 The efficacy of this product was assessed compared to PCV13 and PPSV23 through serologic testing, which demonstrated a noninferior immune response for all 13 serotypes shared in PCV13 and 6 of the 7 additional serotypes shared with PPSV23.19,26 Additional efficacy data was extrapolated from prior PCV13 studies.19

The FDA approved the use of this vaccine to target the 7 additional serotypes not included in PCV13 under the accelerated approval pathway. This requires the manufacturer to conduct a study, which is estimated to conclude in 2027, to assess the ongoing efficacy of this product in order to maintain FDA-approval.19,27

Many similarities exist between PCV20 and PCV13 with regard to storage and administration. Similar to PCV13, PCV20 is available as a single-dose prefilled syringe and should be stored upon receipt in the refrigerator between 2°C to 8°C (36°F to 46°F) and is also stable when stored for up to 4 days at temperatures up to 25°C (77°F). Because of the presence of the adjuvant, it must be shaken vigorously prior to use until the vaccine is a homogenous white suspension, not unlike PCV13. While PCV20 is also administered intramuscularly, no particular administration site is preferred for PCV20 at this time.19

PCV15

Just 1 month after the FDA approval of PCV20, the FDA granted full approval for PCV15 (Vaxneuvance). This vaccine covers 15 serotypes—the 13 serotypes included in PCV13 plus 22F and 33F.18 These 2 additional serotypes are estimated to make up nearly 15% of invasive pneumococcal disease cases.25 Efficacy studies focused on serologic testing and confirmed that for each serotype targeted by PCV13, PCV15 elicited a noninferior immune response, with superiority demonstrated for 22F and 33F, the 2 serotypes targeted in PCV15 that are not present in PCV13.18

PCV15 is currently FDA approved for the prevention of invasive disease caused by the 15 subtypes detailed above in adults at least 18 years of age.18 In December 2021, the FDA accepted the manufacturer’s application to expand PCV15’s indication into the pediatric population. A decision is expected in early July 2022.28

PCV15 is available as a single-dose prefilled syringe and should be administered intramuscularly. No preferred site of administration is noted in the manufacturer labeling.18 Similar to the other PCV products, because of the presence of the adjuvant, PCV15 must be shaken vigorously prior to administration and should be stored upon receipt in the refrigerator between 2°C and 8°C (36°F and 46°F). PCV15 must also be protected from light.18

GUIDELINES

The following recommendations encourage utilization of pneumococcal vaccination unless there is a valid contraindication or precaution to receiving the vaccine.29 All 4 vaccines are contraindicated for patients who have had a severe allergic reaction to a previous vaccine dose or to a vaccine component. For the PCVs, this includes a prior reaction to a diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine given the presence of the adjuvant discussed earlier.17-19 Precaution with all 4 vaccines notes that immunocompromised patients may have a reduced response to the vaccine.17-19,23 Additionally, manufacturer labeling for PPSV23 warns to use caution in those with severely compromised cardiovascular or pulmonary function in whom a systemic reaction would pose a significant risk and to defer vaccination in patients with moderate or severe acute illness.23

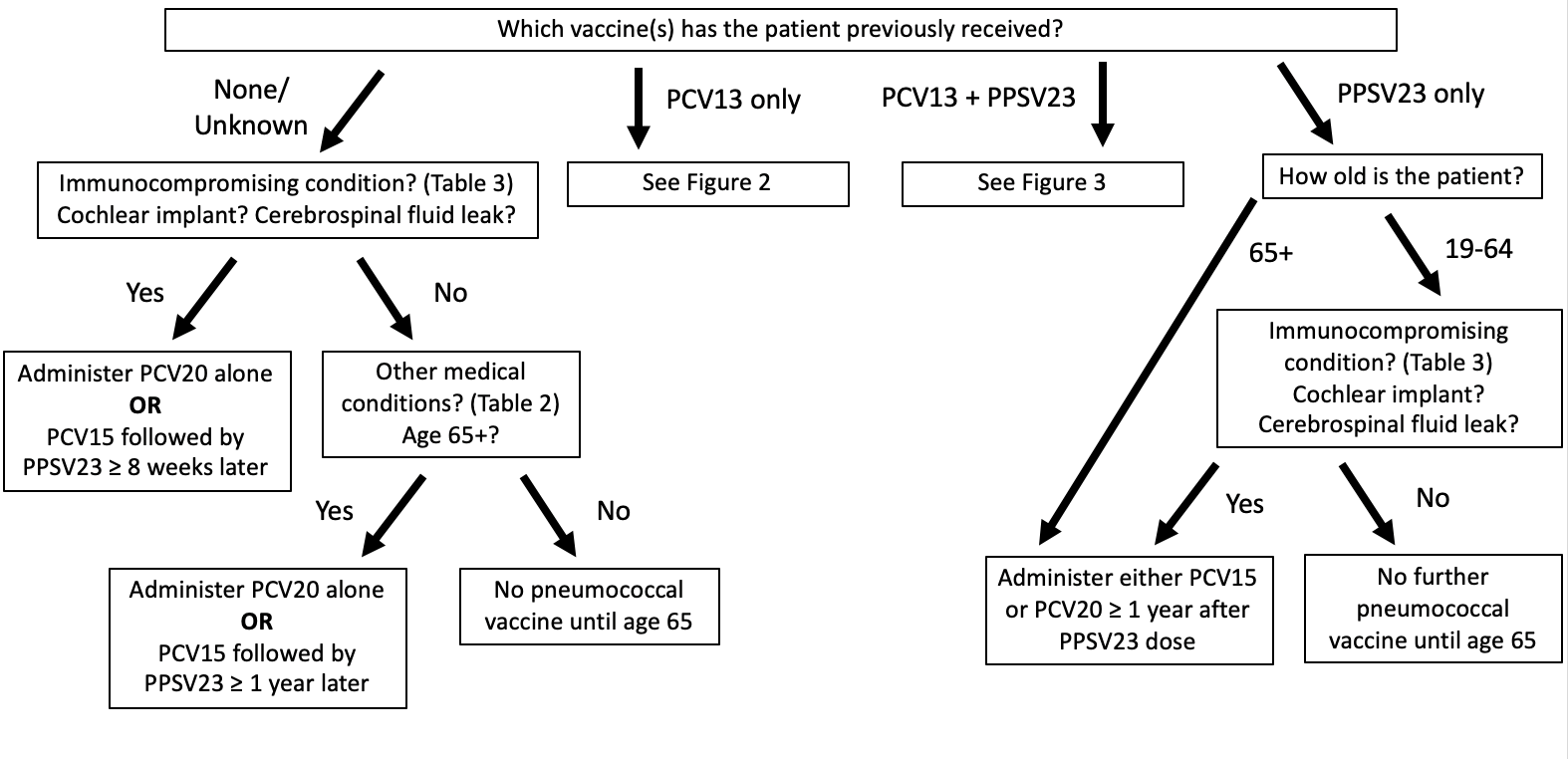

In October 2021, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updated their pneumococcal vaccine recommendations for adults to incorporate PCV15 and PCV20 (FIGURE 1).26 These recommendations update the 2019 ACIP pneumococcal vaccination guidelines specifically for adults aged 19 and older who have not previously received a PCV.

| FIGURE 1. ACIP Recommendations for Pneumococcal Vaccination in Eligible Patients26,30,a |

|

Abbreviations: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; PCV, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PPSV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

a Eligible patients are those over the age of 65 years of age and those aged 19 years and older with underlying medical conditions (TABLE 2), a cochlear implant, a cerebrospinal fluid leak, or an immunocompromising condition (TABLE 3).

|

The ACIP recommends adults aged 65 years and older who have not previously received PCV or whose previous vaccination history is unknown should receive 1 dose of either PCV20 or PCV15. A single dose of PCV20 is sufficient, though when PCV15 is used, it should be followed by a dose of PPSV23. This recommendation was based on data that suggests that the immunogenicity and safety of PCV20 alone or PCV15 in series with PPSV23 were comparable to PCV13 alone or in series with PPSV23.26

The ACIP also recommends a single dose PCV15 followed by a dose of PPSV23 or a single dose of PCV20 alone for all adults aged 19 years or older with underlying medical conditions (TABLE 2), a cochlear implant, a CSF leak, or an immunocompromising condition (TABLE 3) if they have previously not received PCV or if their vaccine history is unknown.26

If a dose of PPSV23 is to be used after PCV15, it is recommended to be given at least 1 year later, based on data that suggests that longer intervals increase the immune response to PPSV23 in immunocompetent adults.26,30 However, PPSV23 may be administered sooner, in as little as 8 weeks after PCV15, if patients have an immunocompromising condition, a cochlear implant, or a CSF leak.26 This is due to the greater risk these patients face for invasive disease caused by serotypes not covered by PCV15 that are targeted by PPSV23.30 If a patient receives a PCV prior to the age of 65, the vaccine doses do not need to be repeated.26

| TABLE 2. Medical Conditions or Risk Factors Warranting Pneumococcal Vaccination as Defined by ACIP Guidelines26,30 |

- Alcoholism

- Chronic heart disease (eg, congestive heart failure and cardiomyopathies, excluding hypertension)

- Chronic liver disease

- Chronic lung disease (eg, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema)

- Cigarette smoking

- Diabetes mellitus

|

|

Abbreviation: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

|

| TABLE 3. Immunocompromising Conditions Warranting Pneumococcal Vaccination as Defined by ACIP Guidelines26,30 |

- Congenital or acquired asplenia

- Sickle cell disease or other hemoglobinopathies

- Chronic renal failure

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Congenital or acquired immunodeficienciesa

- HIV infection

- General malignancy

- Hodgkin disease, leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma

- Iatrogenic immunosuppressionb

- Solid organ transplant

|

Abbreviations: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Includes B- (humoral) or T-lymphocyte deficiency, complement deficiencies (particularly C1, C2, C3, and C4), and phagocytic disorders (excluding chronic granulomatous disease).

b Diseases requiring treatment with immunosuppressants, including long-term corticosteroids and radiation therapy.

|

Patients indicated for PCV15 plus PPSV23 or PCV20 alone who previously received PPSV23 may receive either a single dose of PCV15 or a single dose of PCV20. A second dose of PPSV23 is no longer recommended.26,30

Pneumococcal vaccination is not routinely recommended for all adults aged 19 to 64 years. In fact, the ACIP specifically voted against expanding their updated recommendations to patients 50 years and older without the medical conditions or other risk factors previously listed.26

Notably, PCV13 is no longer recommended for adults, but still remains the only PCV approved by the FDA for use in children.30 Additionally, while the updated guidelines do not include PCV13, it is important to recognize that patients who have previously received a dose of PCV13 should still be treated by the previous ACIP guidelines from 2019.26,30,31 The 2022 recommendations state, “The incremental public health benefits of providing PCV15 or PCV20 to adults who have received PCV13 only or both PCV13 and PPSV23 have not been evaluated,” which highlights the evidentiary gap surrounding mixing and matching available PCVs.26

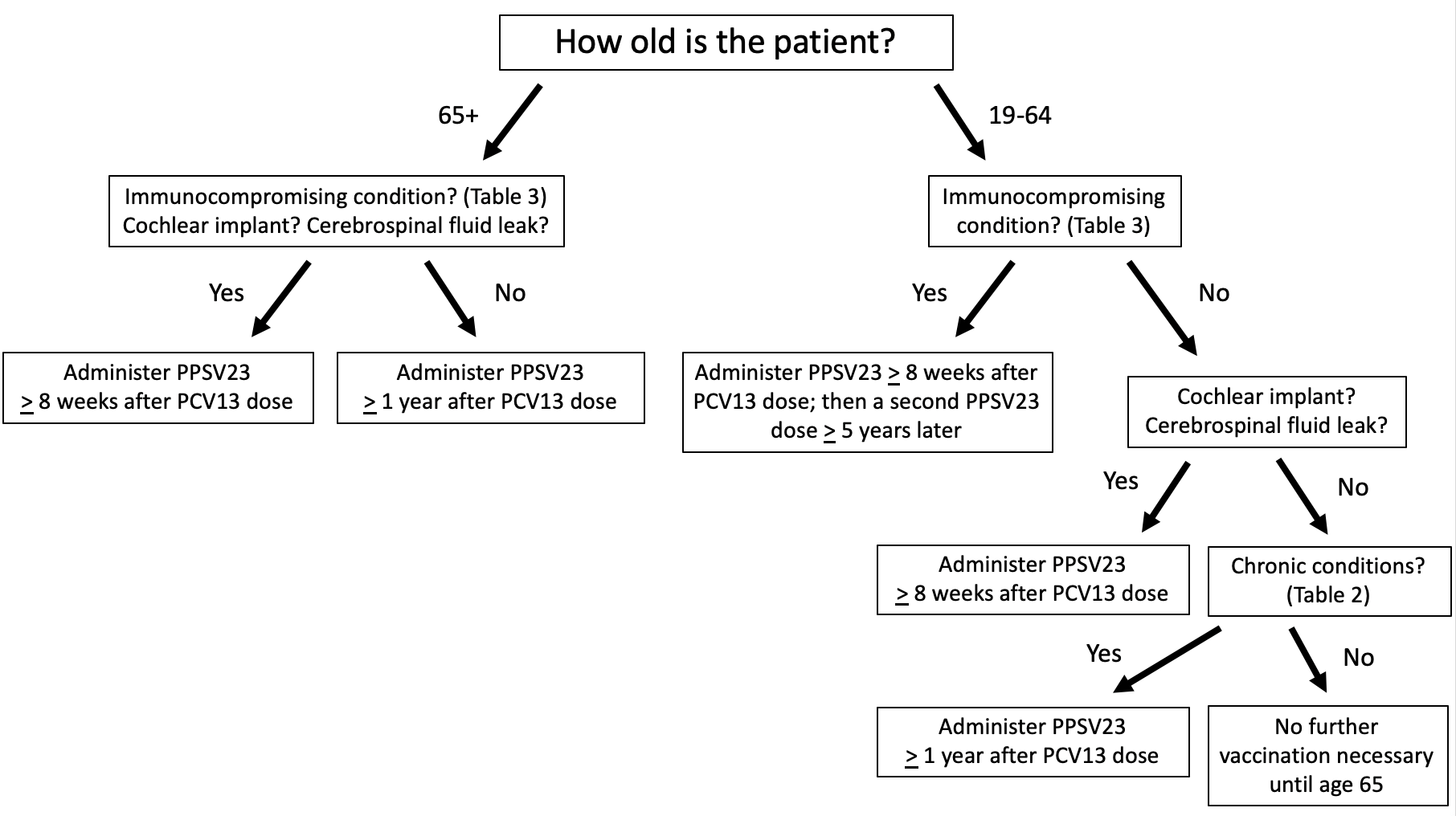

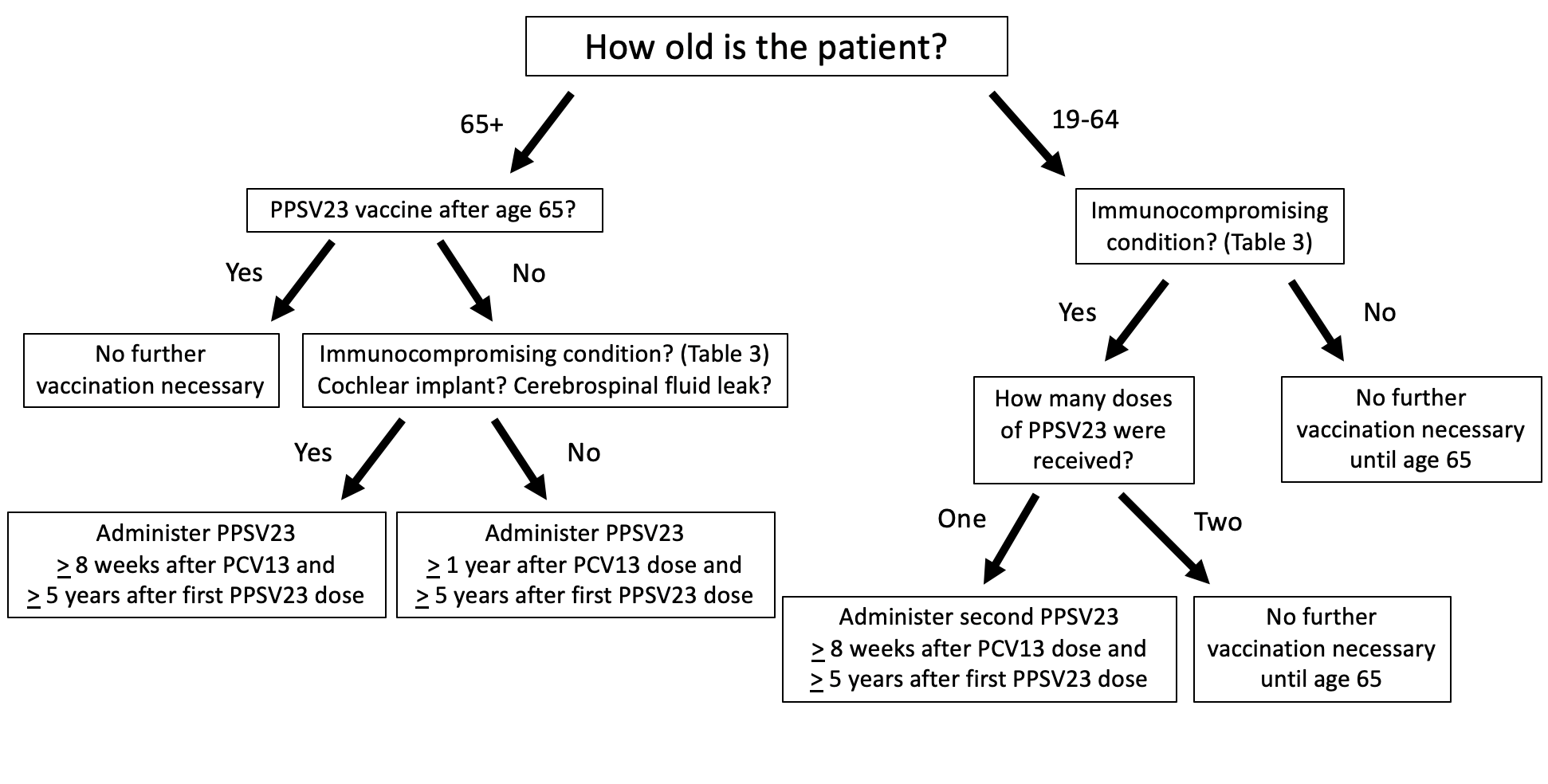

How should patients who have previously received PCV13 be treated? In summary (see FIGURES 2 and 3):30,31

- Adults 65 years of age or older who received PCV13 and PPSV23 in sequence after the age of 65, no further vaccination is necessary

- Adults 65 years of age or older with immunocompromising conditions (TABLE 3), CSF leaks, or cochlear implants who previously received PCV13 but have not received PPSV23 should receive 1 dose of PPSV23 at least 8 weeks after PCV13

- Adults 65 years of age or older with immunocompromising conditions (TABLE 3), CSF leaks, or cochlear implants who previously received PCV13 and PPSV23 before turning 65 should receive 1 dose of PPSV23 at least 8 weeks after PCV13 and at least 5 years after the previous PPSV23 dose

- Adults 65 years of age or older without immunocompromising conditions (TABLE 3), CSF leaks, or cochlear implants who received PCV13 based on shared clinical decision-making, a concept no longer relevant in updated guidelines, should receive PPSV23 at least 1 year after PCV13 and at least 5 years after any PPSV23 received before the age of 65.

- Adults 19 to 64 years of age with immunocompromising conditions (TABLE 3) who have received 1 PCV13 dose but have never received PPSV23 should receive PPSV23 at least 8 weeks after PCV13, and a second PPSV23 at least 5 years after the first PPSV23 dose. A third dose of PPSV23 should be given when the patient reaches 65 years of age as long as at least 5 years have passed since the previous PPSV23 dose.

- Adults 19 to 64 years of age without immunocompromising conditions (TABLE 3) but with CSF leaks or cochlear implants who have received 1 PCV13 dose but have never received PPSV23 should receive a single dose of PPSV23 at least 8 weeks after PCV13. A second dose of PPSV23 should be given when the patient reaches 65 years of age as long as at least 5 years have passed since the previous PPSV23 dose.30,31

Note that only 1 PPSV23 dose is recommended after the age of 65. Thus, if patients 19 to 64 years of age who are indicated for 2 or 3 doses of PPSV23 receive their first dose after the age of 65, no repeat vaccination is recommended.30,31

| FIGURE 2. ACIP Recommendations for Pneumococcal Vaccine Administration in Patients Previously Immunized With PCV13 Only |

|

|

Abbreviations: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; PCV, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PPSV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

|

| Figure 3. ACIP Recommendations for Pneumococcal Vaccine Administration in Patients Previously Immunized With PCV13 and PPSV2330,31 |

|

|

Abbreviations: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; PCV, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PPSV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

|

Patient Case

The introduction of PCV15 and PCV20 have allowed the ACIP’s recommendations to be simplified significantly as opposed to the 2019 guidelines. Still, individual patient circumstances must be considered, and it can be a challenge to keep it all straight. For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed the PneumoRecs VaxAdvisor mobile app to help vaccine providers recognize which patients are appropriate candidates for which vaccines and when.32 This user-friendly app prompts providers with a series of questions to determine the best treatment course for each individual patient. A desktop version is also available at: https://www2a.cdc.gov/vaccines/m/pneumo/pneumo.html.32

| PATIENT CASE |

|

Note: You are encouraged to use the PneumoRecs VaxAdvisor mobile app to help you with the following case.

A 24-year old male comes to your pharmacy to fill a prescription. You notice that he has a pack of cigarettes in his pocket and come to find out through conversation that he smokes 0.5 packs per day and has been smoking since age 19. In discussion, you find out that he has never received a pneumococcal vaccine in the past.

-

Which of the following would be the best recommendation for this patient?

- One dose of PCV15 alone

- One dose of PCV20 alone

- One dose of PPSV23 alone

- No pneumococcal vaccination until he turns 65

The correct answer is B. Using the PneumoRecs VaxAdvisor app, you will find that patients 19-64 years of age with a risk factor/chronic condition (eg, cigarette smoking) and no or unknown prior pneumococcal vaccination should receive a single dose of PCV20 alone or a single dose of PCV15 followed by PPSV23 at least 1 year later. You may also follow along the pathway in FIGURE 1.

After you make your recommendation, he remembers that he has actually previously received PCV13 around his 21st birthday. Given this updated information, which of the following would be the best recommendation for this patient?

- One dose of PPSV23 when the patient turns 65

- One dose of PPSV23 now and another PPSV23 dose 5 years from now

- One dose of PPSV23 now and another PPSV23 dose at age 65

- One dose of PPSV23 now, another PPSV23 dose 5 years from now, and a third dose at age 65

The correct answer is C. Using the PneumoRecs VaxAdvisor app, you will find that patients 19-64 years of age with a risk factor/chronic condition (eg, cigarette smoking) who have previously received PCV13 and have not previously received PPSV23 should receive a single dose of PPSV23 at least one after PCV13 and a second PPSV23 dose at age 65, as long as 5 years have passed since the first PPSV23 dose. You may also follow along the pathway in FIGURE 2.

|

ADDRESSING BARRIERS TO VACCINE ADMINISTRATION

Pharmacists have the skills to address many of the barriers that may affect patient acceptance of the pneumococcal vaccine relating to vaccine hesitancy, patient safety, determination of patient vaccination history, sequencing of the vaccine, convenience with other vaccines, and costs. Pharmacists should engage in the process of shared decision-making with patients as part of the Pharmacist Patient Care Process and must proactively work to immunize patients. Participating in shared decision-making with patients can increase vaccination rates, and failure to engage in these conversations can have consequences of poor outcomes.33-35

Vaccine Hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy is defined as “a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite available vaccination services,”36 and was considered 1 of the top 10 threats to global health according to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019, even before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.37 Undoubtedly, hesitancy is playing a role in suboptimal pneumococcal vaccination rates. In 2020, 71.2% of adults aged 65 and older had received a pneumococcal vaccine, which was well below the Health People 2020 goal of 90%.38,39

As the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) suggests, pharmacists can help patients overcome vaccine hesitancy and improve vaccination rates by examining the patient history and screening for immunization needs; providing counseling and education on guidelines, recommendations, and safety of vaccination; ensuring a sufficient stock of vaccines is available for the patient population to be served; promoting organizational vaccine initiatives through administrative measures; and educating the public through community outreach.34

In addition to this generalized approach, it is beneficial for pharmacists to employ patient-specific counseling to illicit change. This technique, known as motivational interviewing, is based on 3 principles:40

- Building a trusting relationship between the patient and pharmacist;

- Engaging the patient in an ongoing dialogue about the proposed change; and

- Helping the patient find their reasons for implementing the change.40

The principles of motivational interviewing help not only build upon the pharmacist-patient relationship but help institute meaningful change by allowing patients to feel in control of the decisions they make.

It is important for pharmacists to recognize reasons for vaccine hesitancy to help patients overcome this hurdle. The “3 Cs” Model considers the reasons for vaccine hesitancy to include competing priorities (“Complacency”), challenges with receiving the vaccine (“Convenience”), and the barrier of distrust or misconceptions regarding vaccines and the health care system (a lack of “Confidence”).41

Complacency

Complacency is the concept that patients forgo necessary care because they do not feel a sense of urgency to seek it out. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a positive impact on complacency. Upon the declaration of the pandemic in March 2020, vaccine rates dropped dramatically, but have steadily risen since then.42 Presumably, the introduction of a novel virus brought infectious disease to the forefront of patients’ minds. Interestingly, 1 study found there were significant positive correlations between search volume indexes for coronavirus and search terms for pneumococcal and influenza vaccines.43 The authors concluded the findings may predict changes in vaccination rates as online interest in the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines typically follow a seasonal pattern in September to November versus February and March as observed in the study.43 Pharmacists should work to capitalize on this opportunity by educating patients about all vaccines they may be eligible for, including pneumococcal vaccines based on the most up-to-date guidelines.

Convenience

Vaccines administered in a multi-dose series that require patients to return to the site of care for follow-up visits can also be a barrier. Pharmacists are in a unique position as 1 of the most accessible health care providers to overcome the barrier of inconvenience. Approximately 90% of Americans reside within 2 miles of a pharmacy. Pharmacies provide increased access to vaccination administration with longer hours than physician offices, plus added weekend availability. Many primary care providers also do not regularly stock vaccines in their offices. Patients with chronic disease states who have frequent contact with a pharmacist present a great opportunity to increase vaccination rates.44 Pharmacy technicians can also get involved in the process by tracking vaccine administration, scheduling future vaccination appointments, and reminding patients about follow-up visits.

Patients may have concerns about taking multiple trips to the pharmacy or to their provider to receive different vaccines for which they are indicated. Reassure patients that PCV13, PCV15, PCV20, and PPSV23 are all inactivated vaccines, and for that reason other vaccines can be given at the same time if indicated. A few important notes regarding coadministration of other vaccines:30,45

- Any of these vaccines may be coadministered with the inactivated influenza vaccine. Although PCV13 labeling suggests antibody response may be lower if it is given with the influenza vaccine, this does not reduce vaccine efficacy, and the CDC advocates giving both on the same day

- Currently, there are no data regarding the safety and efficacy of coadministration of PCV15 and PCV20 during the same visit with other vaccines, including the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine or the zoster vaccine in adults

- Similarly, evidence is insufficient to determine safety and efficacy of coadministration of PCV13 with Tdap, though data are available that suggest PCV13 may be safely coadministered with the adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine without compromising efficacy of either vaccine46

- When PPSV23 was given at the same visit with the zoster vaccine, a clinical study showed that the efficacy of the zoster vaccine was reduced compared to the response seen in patients who received the vaccines 4 weeks apart. Still, the CDC recommends the use of these vaccines together for eligible patients for the purpose of convenience

- Remember that PCV and PPSV23 should not be given together.30,45

Another challenge related to convenience is determining which vaccine schedule the patient should be following. In order to provide the most patient-centric care possible, patients should be encouraged to reach out to previous employers, schools or colleges, and health care providers to determine which vaccines have been received in the past. State registries can help prevent unnecessary vaccination and billing and reimbursement problems, while also helping to avoid missed opportunities for vaccination. If reasonable attempts fail to produce a vaccination record, the simplified recommendations from the 2022 ACIP guidelines allow pharmacists to overcome this barrier more easily by following the straightforward schedules discussed previously.

Confidence

One of the most significant barriers to vaccine uptake is hesitant patients’ lack of confidence and trust in not only the safety and efficacy of vaccines themselves, but also the health care providers administering them and the system that delivers them.41 Additionally, misconceptions arise for a number of reasons, including, but not limited to, negative media coverage and resulting distrust of the pharmaceutical industry; recommendations from influential antivaccination thought leaders (eg, celebrities); religious, cultural, or socioeconomic factors; knowledge gaps regarding the risks and benefits of vaccines; and negative prior experiences with other vaccines.47,48

A recent survey found that one of the most significant reasons for vaccine hesitancy is the concern regarding serious side effects from vaccines, highlighting the importance of pharmacists in reassuring patients about pneumococcal vaccine safety. 47 Pharmacists should educate patients that the safety of vaccines is closely monitored by the CDC using 3 systems, including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment Project (CISA). Additionally, the CDC and FDA inform health officials and the public of any problems found with a vaccine.49

The most common side effects from pneumococcal vaccines are mild, lasting 1 or 2 days.49 Common adverse events reported with the PCV and PPSV are pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site; limited mobility of the injected arm; fatigue; headache; chills; decreased appetite; generalized muscle pain; and joint pain.17-19,23 PCV15 and PCV20 were compared to PCV13 in pivotal studies and have numerically similar rates of adverse events.17-19,26 There are mixed results surrounding the safety of PPSV23 compared with PCV13. In 1 trial, adverse reaction rates were similar between vaccines.50 In a second trial that was done in patients 70 years of age or older, PPSV23 was associated with a statistically significantly greater proportion of adverse events compared to PCV13.51 However, the majority of these adverse events were mild or moderate in severity.

CONCLUSION

Streptococcus pneumoniae can cause serious illness including sepsis, meningitis, and pneumonia with or without bacteremia. As a result of new vaccines becoming available in 2021, the ACIP simplified its pneumococcal vaccine schedule, significantly reduced the role of PCV13, and removed the concept of shared decision-making in determining which patients were appropriate candidates for certain vaccines. These new guidelines have highlighted the importance of the recently approved PCV15 and PCV20 for adult patients. Pharmacists play a major role in educating patients on vaccine eligibility and assisting them in overcoming barriers to care. As the most accessible health care provider in the community, pharmacists must utilize their knowledge and relationships with patients to ensure patients receive the most appropriate vaccination(s) as suggested by the updated guidelines.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine-preventable adult diseases. Updated March 30, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/vpd.html

- World Health Organization (WHO). Pneumonia. Updated November 11, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/pneumonia

- Jain V, Vashisht R, Yilmaz G, Bhardwaj A. Pneumonia pathology. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 12, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526116/

- Nowicki J, Murray MT. Bronchitis and pneumonia. Textbook of Natural Medicine. 2020;1196-1201.e1. doi:1016/B978-0-323-43044-9.00155-2

- Pneumococcal disease. Updated August 18, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/pneumo.html

- Dion CF, Ashurst JV. Streptococcus pneumoniae. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 30, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470537/

- Grief SN, Loza JK. Guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of pneumonia. Prim Care. 2018;45(3):485-503. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2018.04.001

- Rotstein C, Evans G, Born A, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2008;19(1):19-53. doi:10.1155/2008/593289

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67. doi:10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST

- Lanks CW, Musani AI, Hsia DW. Community-acquired pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(3):487-501. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.008

- Pneumonia. Updated February 1, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/pneumonia.htm

- Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2019. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2021:70(9):1-113. Published July 26, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr70/nvsr70-09-508.pdf

- Pneumococcal disease—surveillance and reporting. Updated September 1, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/surveillance.html

- Pneumococcal disease—risk factors and how it spreads. Updated September 1, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/about/risk-transmission.html

- About pneumococcal vaccines. Updated January 24, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/about-vaccine.html

- Principles of vaccination. The Pink Book. Updated August 18, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/prinvac.html

- Prevnar 13 (pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine) prescribing information. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals LLC; July 2019.

- Vaxneuvance (pneumococcal 15-valent conjugate vaccine) prescribing information. Merck & Co., Inc.; July 2021.

- Prevnar 20 (pneumococcal 20-valent conjugate vaccine) prescribing information. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals LLC; June 2021.

- HogenEsch H, O’Hagan DT, Fox CB. Optimizing the utilization of aluminum adjuvants in vaccines: you might just get what you want. NPJ Vaccines. 2018;3:51. doi:10.1038/s41541-018-0089-x

- Adjuvants and vaccines. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/adjuvants.html

- Nuorti JP, Whitney CG; CDC. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-11):1-18.

- Pneumovax 23 (pneumococcal vaccine polyvalent) prescribing information. Merck & Co., Inc.; April 2021.

- Johnstone J, Marrie TJ, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR. Effect of pneumococcal vaccination in hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1938-1943. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.18.1938

- Kobayashi M. Considerations for age-based and risk-based use of PCV15 and PCV20 among U.S. adults and proposed policy options. National Center for Immunization & Respiratory Diseases; CDC. Published October 20, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-10-20-21/02-Pneumococcal-Kobayashi-508.pdf

- Kobayashi M, Farrar JL, Gierke R, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among U.S. adults: Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(4);109-117. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7104a1

- US Food & Drug Administration (FDA). BLA approval and BLA accelerated approval for pneumococcal 20-valent conjugate vaccine. Published June 10, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/150021/download

- Shasteen H. FDA delays decision on Merck's pediatric pneumococcal vaccine. BioSpace. Published April 1, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.biospace.com/article/fda-extends-date-for-approval-of-merck-s-pneumococcal-vaccine/

- org. Standing orders for administering pneumococcal vaccines (PCV15, PCV20, and PPSV23) to adults. Published March 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p3075.pdf

- org. Ask the experts: pneumococcal vaccines. Updated March 22, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.immunize.org/askexperts/experts_pneumococcal_vaccines.asp

- Matanock A, Lee G, Gierke R, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(46):1069-1075. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6846a5

- PneumoRecs VaxAdvisor mobile app for vaccine providers. Updated February 9, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/pneumoapp.html

- Kuehne F, Sanftenberg L, Dreischulte T, Gensichen J. Shared decision making enhances pneumococcal vaccination rates in adult patients in outpatient care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9146. doi:10.3390/ijerph17239146

- American Society of Health System Pharmacists Council on Professional Affairs. ASHP guidelines on the pharmacist's role in immunization. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(13):1371-1377. doi:10.1093/ajhp/60.13.1371

- American Journal of Managed Care. Addressing barriers to optimal community-based vaccination. AJMC. Published July 26, 2018. Accessed September 28, 2020. https://www.ajmc.com/view/addressing-barriers-to-optimal-communitybased-vaccination

- Marti M, de Cola M, MacDonald NE, et al. Assessments of global drivers of vaccine hesitancy in 2014—looking beyond safety concerns. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172310. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172310

- Ten threats to global health in 2019. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). Adults aged 65 and over who report ever having a pneumonia vaccine by sex. Timeframe: 2020. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/adults-age-65-plus-who-report-ever-having-a-pneumonia-vaccine-by-sex/

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Immunization and infectious diseases. Healthy People 2020. Updated February 6, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives

- Gagneur A. Motivational interviewing: a powerful tool to address vaccine hesitancy. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2020;46(4):93-97. doi:10.14745/ccdr.v46i04a06

- American College of Cardiology (ACC). Overcoming vaccine hesitancy: helping patients help themselves. Cardiology Magazine. Published October 7, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2021/10/01/01/42/cover-story-overcoming-vaccine-hesitancy-helping-patients-help-themselves

- Hong K, Zhou F, Tsai Y, et al. Decline in receipt of vaccines by Medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, 2020. 2021;70:245-249. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7007a4

- Paguio JA, Yao JS, Dee EC. Silver lining of COVID-19: Heightened global interest in pneumococcal and influenza vaccines, an infodemiology study. Vaccine. 2020;38(34):5430-5435. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.069

- Tak CR, Marciniak MW, Savage A, Ozawa S. The essential role of pharmacists facilitating vaccination in older adults: the case of Herpes Zoster. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(1):70-75. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1637218

- Administering pneumococcal vaccines. Updated January 24, 2022. Updated June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/administering-vaccine.html

- Min JY, Mwakingwe-Omari A, Riley M, et al. The adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine co-administered with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults aged ≥50 years: a randomized trial. J Infect. 2022;84(4):490-498. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.12.033

- Gatwood J, McKnight M, Frederick K, et al. Extent of and reasons for vaccine hesitancy in adults at high-risk for pneumococcal disease. Am J Health Promot. 2021;35(7):908-916. doi:10.1177/0890117121998141

- Summary WHO SAGE conclusions and recommendations on vaccine hesitancy. Published January 2015. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/demand/summary-of-sage-vaccinehesitancy-en.pdf?sfvrsn=abbfd5c8_2

- Pneumococcal vaccines—safety information. Updated September 2020. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/pneumococcal-vaccine.html.

- Jackson LA, Gurtman A, van Cleeff M, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults. Vaccine. 2013;31(35):3577-3584. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.085

- Jackson LA, Gurtman A, Rice K, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults 70 years of age and older previously vaccinated with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Vaccine. 2013;31(35):3585-3593. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.010

Additional Sources for Audio

- Fuller H, Dubbala K, Obiri D, et al. Addressing vaccine hesitancy to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 vaccination uptake across the UK and US. Front Public Health. 2021;9:789753. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.789753

- Positive top-line results of Pfizer’s Phase 3 study exploring coadministration of Prevnar 20 with seasonal flu vaccine in older adults released. Published September 29, 2021. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/positive-top-line-results-pfizers-phase-3-study-exploring.

- gov Identifier: NCT04887948. Safety and immunogenicity study of 20vPnC when coadministered with a booster dose of BNT162b2. Updated March 25, 2022. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04887948

- Positive top-line results of Pfizer’s Phase 3 study exploring coadministration of PREVNAR 20 with Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in older adults released. Published January 12, 2022. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/positive-top-line-results-pfizers-phase-3-study-exploring-0

Back to Top