Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Crafting the New Treatment Mix in CLL: Pharmacist Insights on Delivering Effective Care With Targeted Therapy

Dr. Dotson: Good morning, and welcome to the symposium "Crafting the New Treatment Mix in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL): Pharmacist Insights on Delivering Effective Care With Targeted Therapy." My name is Emily Dotson. The other panelists with me are Dr. Peter Campbell and Dr. Sarah Stump.

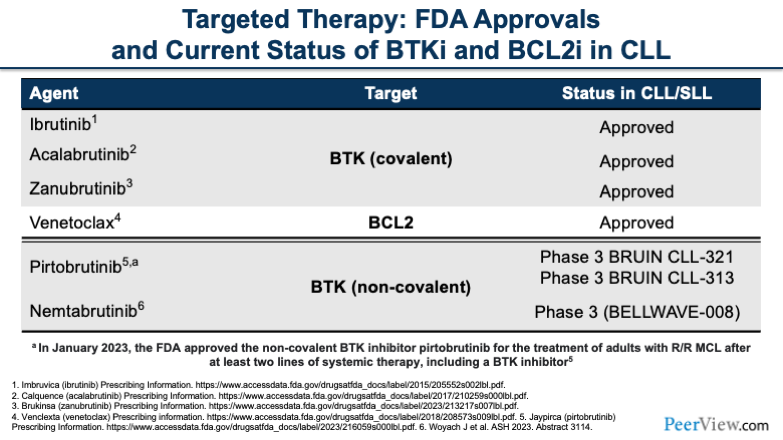

Let’s dive into our targeted therapies. The current FDA approvals that we have include three BTK inhibitors, ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, and the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax. These are all currently approved with the combination targets between BTKs and BCL2. There are two additional agents on the horizon, including pirtobrutinib and nemtabrutinib.

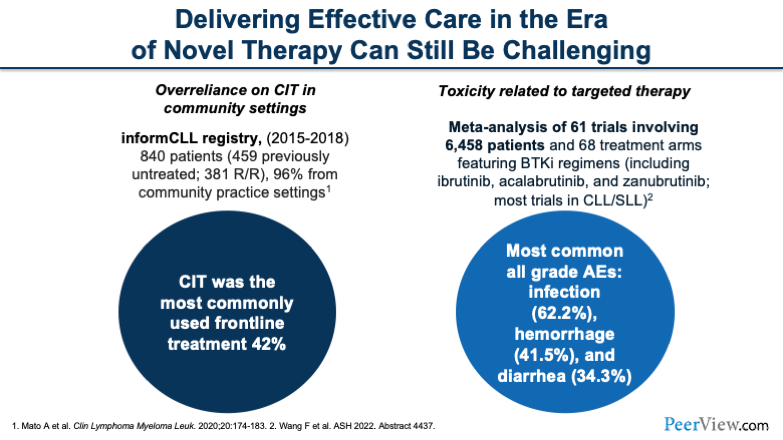

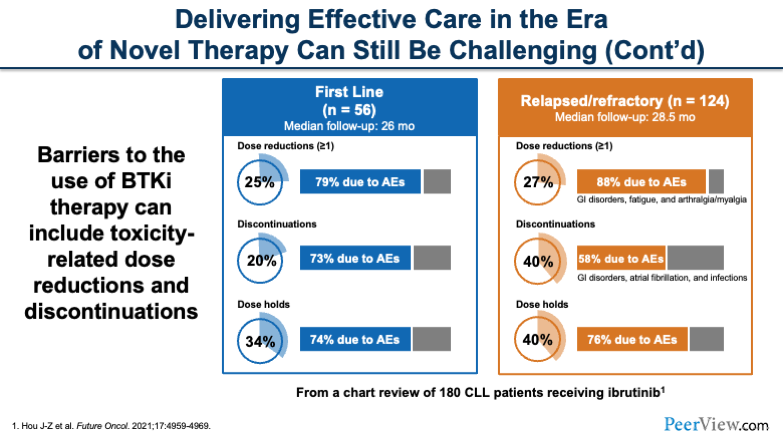

I'd like to call out a couple of things. Despite these novel therapies, we continue to have some challenges in this area. There tends to be a bit of overreliance in the chemoimmunotherapy setting based on a registry that looked at a variety of therapies across a number of years. In addition, we have a number of toxicities that are also related to these targeted agents that can be very challenging.

So it's very important for us to be aware of those barriers and to be able to empower our patients to stick with their therapies. We know in the first-line setting and the relapsed/refractory (R/R) setting, there are a number of dose reductions, discontinuations, and dose holds that occur because of adverse events.

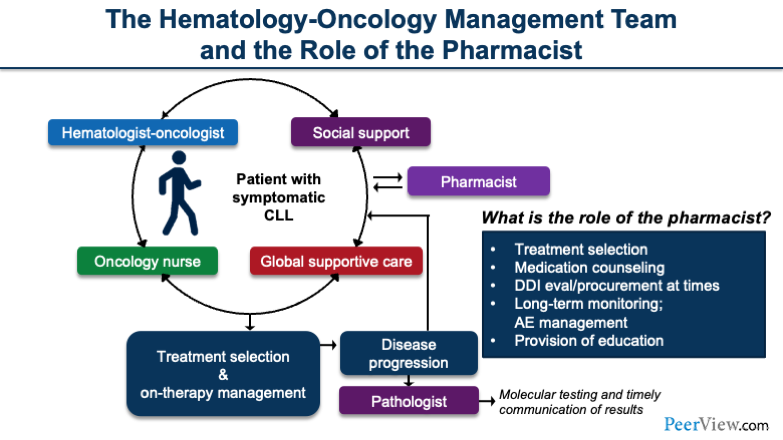

The hematology-oncology management team, which consists of a variety of people, is important when taking care of the patient. We can see here that we have the hematology-oncologist; an oncology nurse or an oncology nurse provider; and global supportive care, which may include cardio-oncology. It may also include supportive services for drug procurement, grant aid, and really helpful financial aid services to help get the medication in the hands of the patient.

In addition, the pharmacist plays an equally important role in terms of treatment selection, medication counseling, reviewing drug–drug interactions, procuring drugs in a timely manner, long-term monitoring, follow-up plans, adverse event management, and providing education to health care providers.

Our goals for this activity are to help you understand the mechanistic/pharmacokinetic profiles and current evidence supporting BTK-inhibitor and BCL2-inhibitor approaches in CLL. We hope to equip you with the skills you need to develop pharmacist-informed management plans that include targeted therapies for treatment-naïve and R/R settings.

At the very end, we'll provide you with some collaborative guidance to address issues such as care coordination, drug interactions, patient counseling, staff education, safety, and dosing considerations.

Dr. Dotson: With that, I'll turn it over to my colleague, Dr. Campbell, who will introduce BTK inhibitors.

Dr. Campbell: Thank you so much for that.

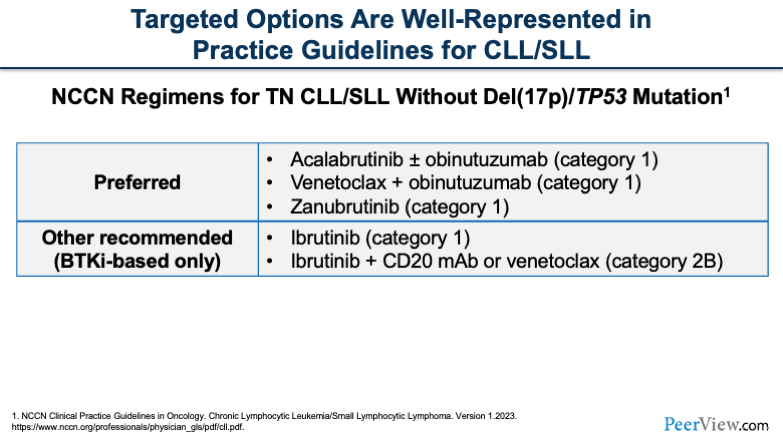

We're going to take a quick look at some of the NCCN recommendations. On this slide, what you'll see are the NCCN recommendations for treatment-naïve CLL in patients who do not have deletion 17p (del[17p]) or TP53 mutations.

The preferred regimens include our BTK inhibitors with or without an anti-CD monoclonal antibody, venetoclax plus obinutuzumab or with ibrutinib either alone or with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody.

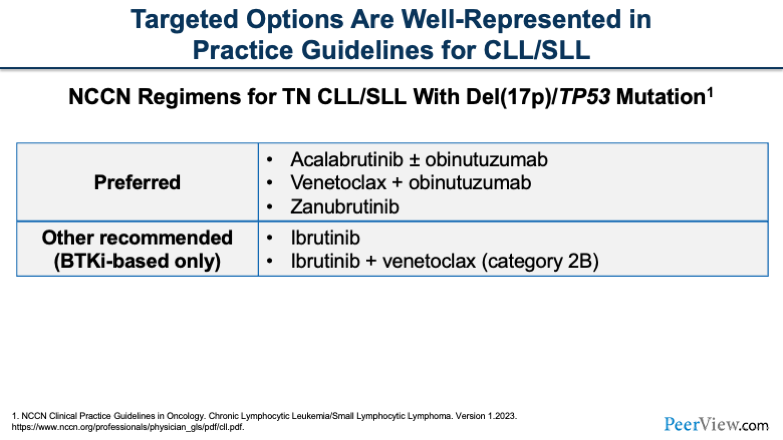

Nowadays, if we look at patients who have a del(17p) or TP53 mutation, we see very similar treatment regimens, whereas historically, this may have been different. But these regimens have aligned more and more over the recent years.

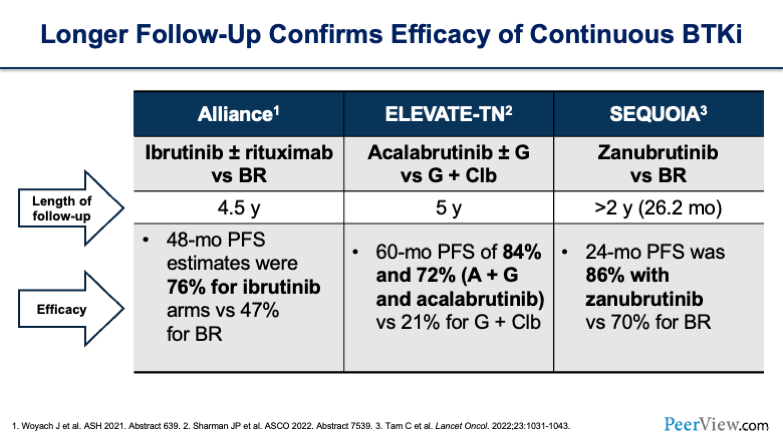

In this day and age, one of the great things about BTK inhibitors is that we have therapies that people can stay on for a long time. And when we're looking at the data, one thing that we want to look at is the length of follow-up and what the overall response rates (ORR) are over time. You'll see long follow-ups for the Alliance, ELEVATE-TN, and SEQUOIA trials, with all of them being over 2 years from median follow-up.

If you look at efficacy, you see remarkable results across all of these trials: 76% for ibrutinib, 84% and 72% for acalabrutinib, and 86% for zanubrutinib. So, impressive results with long-term follow-up.

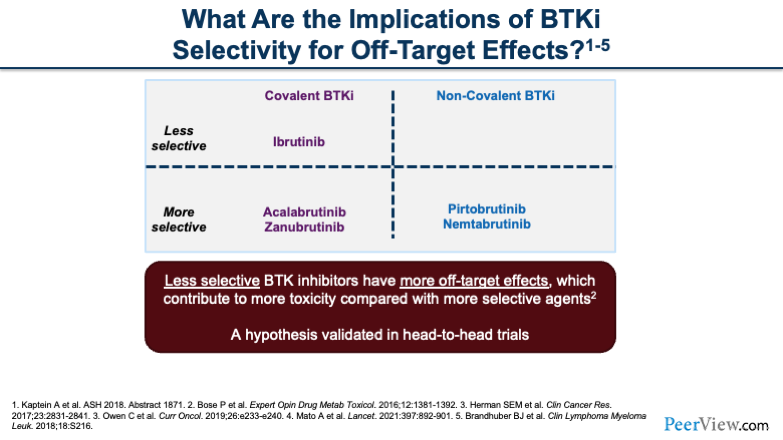

Now, when we think about TKIs, the things we have to think about across the board are mechanisms of action (MOAs) and off-site targets. The reason that these things are important is because when we're looking at selectivity of these BTK inhibitors, we have to start thinking about what toxicities these drugs are going to be prone to have on our patients.

If you look on the left of the slide, you'll see the covalent BTK inhibitors: ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib. And what really differentiates them is that acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib are a bit more selective; therefore, you'll see when we go through some of the toxicity profiles later that acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib may be a little bit better tolerated compared with ibrutinib. When you look at the non-covalent BTK inhibitors that we'll touch on briefly later, you’ll also see that they are more selective, as well. Hopefully, this selectivity can help reduce toxicity for patients.

Challenge Question

Which statement reflects your understanding of BTKi selectivity differences and off-target effects?

- I’m not sure of the BTKi selectivity differences and off-target effects

- Less selective BTKi have fewer off-target effects

- More selective BTKi have more off-target effects

- Less selective BTKi have more off-target effects

- Less and more selective BTKi have similar off-target effects

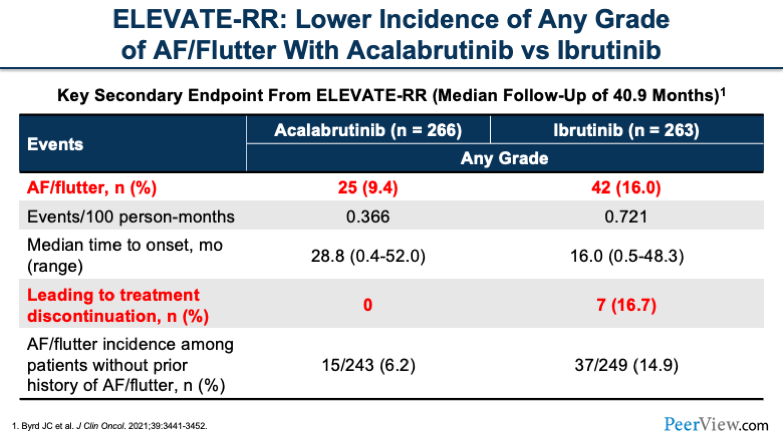

If we look at the ELEVATE-RR trial, we see that atrial fibrillation (AF)/flutter is a very common side effect that we look for with BTK inhibitors. You'll notice that acalabrutinib, being more selective as compared with ibrutinib, had lower rates of AF/flutter.

Also, what you see is those that had side effects leading to treatment discontinuation were lower, with no patients on acalabrutinib discontinuing because of cardiac side effects. You can see, acalabrutinib is a little bit more tolerated, especially for high-profile side effects that we typically anticipate.

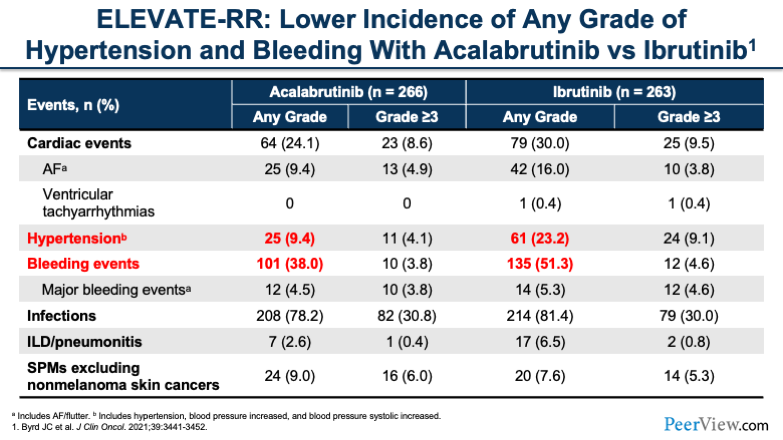

Now, if we look further at some of the other toxicities that we commonly associate with BTK inhibitors, such as hypertension and bleeding events, we also see that acalabrutinib had lower rates of both of these toxicities, both for any grade and grade 3 or greater.

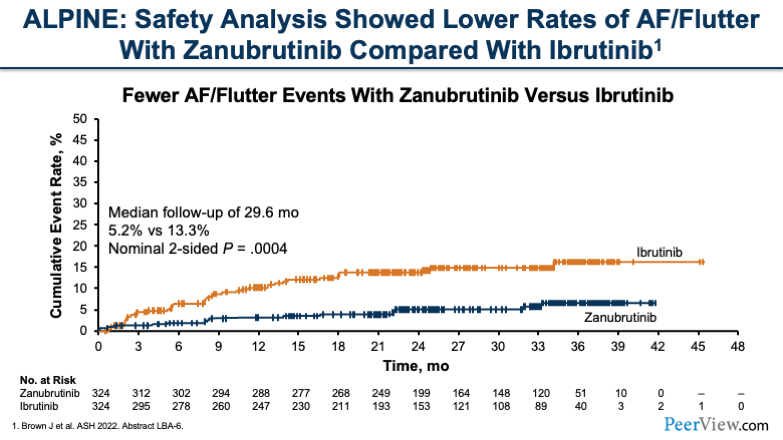

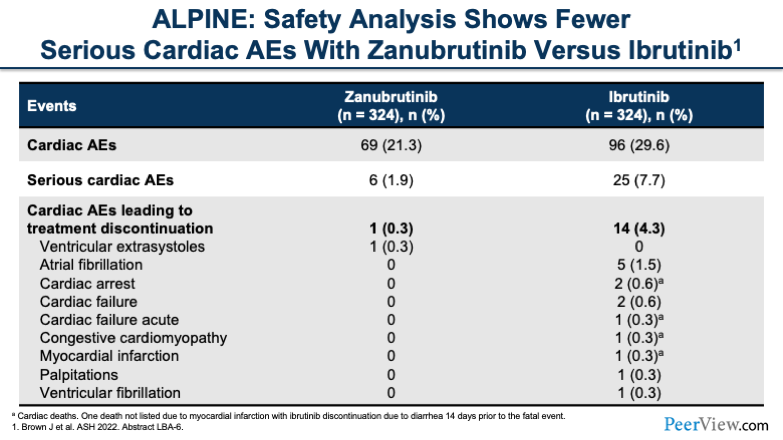

Now, if we move to zanubrutinib and take a look at the ALPINE study, what we see is also a lower rate of AF/flutter with zanubrutinib compared with ibrutinib. If you look at this graph here, what you'll see is that over time, there's a sustained difference in toxicities for AF/flutter.

And when we look at the rest of the toxicity profile, what we see is cardiac adverse events led to lower treatment discontinuation with zanubrutinib compared with ibrutinib, and overall, cardiac adverse events were lower. The selectivity of BTK inhibitors in the real-life setting can result in fewer toxicities for most patients. And with that, I will now pass it over to Emily.

Dr. Dotson: Okay. We know that when we utilize BTK inhibitors, there are a number of issues to consider as patients start on therapy. And this brings us to the non-covalent introduction of our talk.

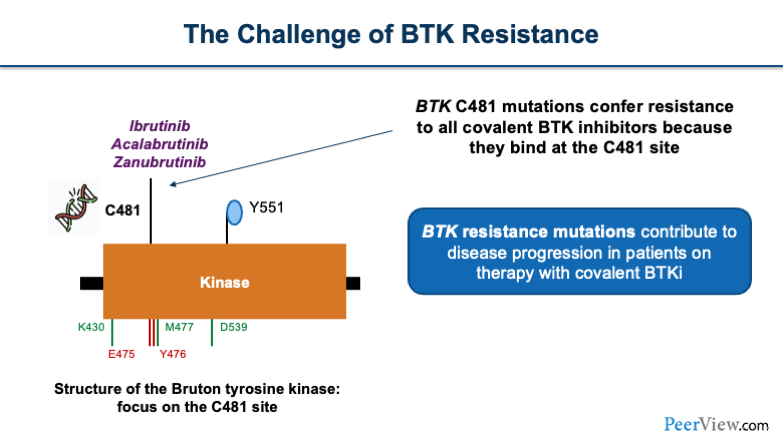

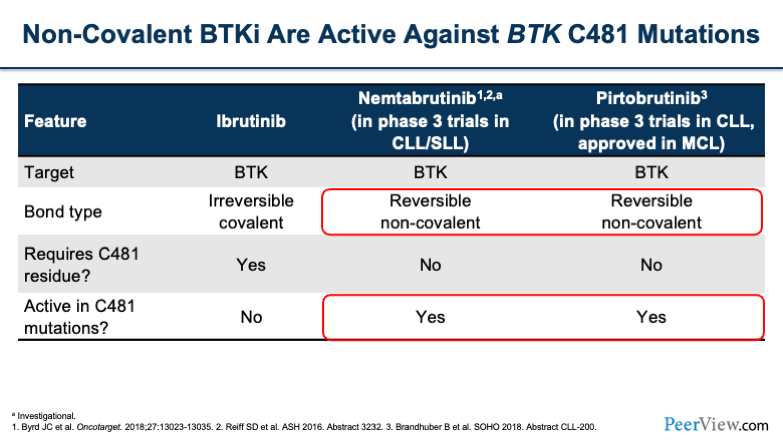

There's a challenge of BTK resistance that occurs. Ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib all bind at the Bruton tyrosine kinase. And on this, there is a residue that is the cysteine 481 (C481) residue. When this C481 mutation occurs at the binding pocket, the covalent BTK inhibitors are unable to bind. Therefore, that downstream impact causes progression of the disease.

We have a number of agents that are being studied to overcome that resistance. These are known as non-covalently bounded BTK inhibitors. Two medications that are currently being reviewed are nemtabrutinib and pirtobrutinib. The targets for these are both BTK, however, the bonding type is reversible and non-covalent, which means that they are active in C481 mutations.

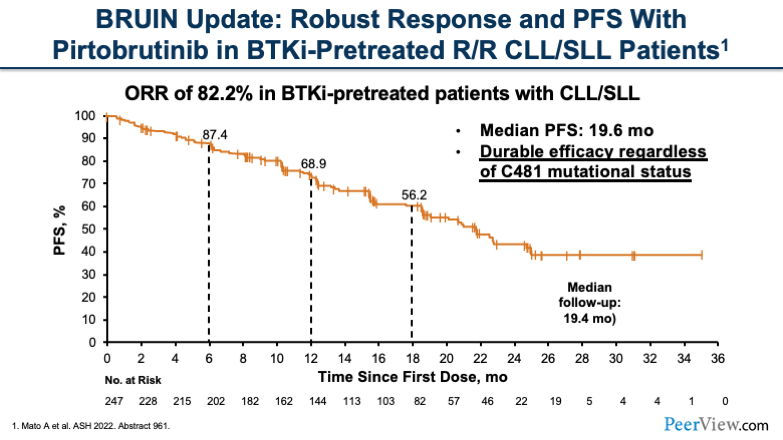

There are a few studies that review the impact of these non-covalent BTK inhibitors. The BRUIN update was a study testing pirtobrutinib looking at patients in the R/R setting. Patients overall were refractory to a BTK inhibitor and had pretreatment.

The ORR was 82.2% in this heavily treated patient population. The median progression-free survival was 19.6 months, and this was a durable efficacy that was seen across the board in the mutation status of the patients.

Challenge Question

Make a choice. Select the statement that matches current evidence on the non-covalent BTKi pirtobrutinib in pretreated CLL/SLL.

- I’m not sure

- Pirtobrutinib is not active in BTKi-pretreated patients

- Pirtobrutinib is not active in BTKi/BCL2i-pretreated patients

- Pirtobrutinib is active in both BTKI-pretreated and BTKi/BCL2i-pretreated patients

- Pirtobrutinib is active in BCL2i-pretreated but not active in BTKi-pretreated patients

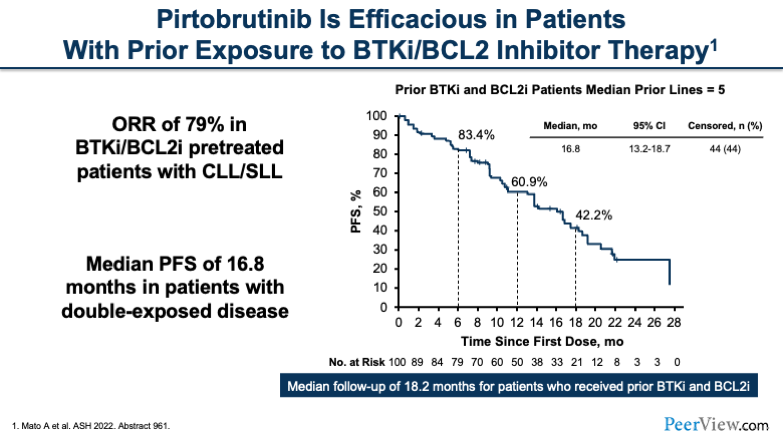

In addition, there was another group of patients who were double-exposed; they had BTK inhibitor and BCL2 inhibitor exposure. The ORR of this heavily treated group was 79%. The median prior lines of therapy were five. The median duration in months was about 16.8.

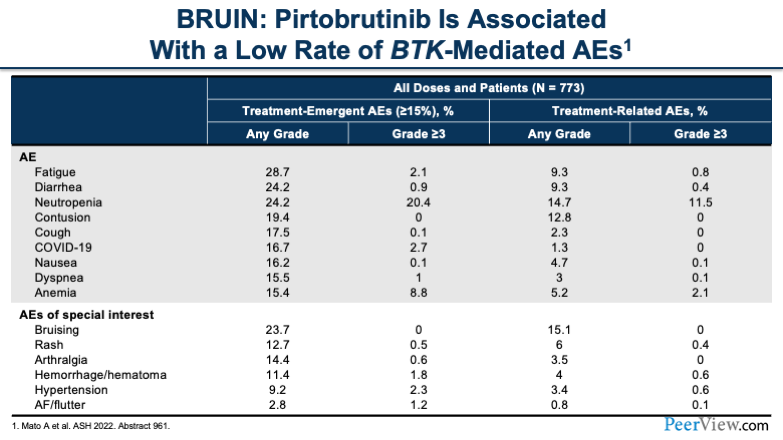

Additionally, pirtobrutinib has been associated with low rates of BTK-mediated adverse events. At the very bottom of the table, I'll draw your attention to some of the special-interest adverse events that we see, specifically hypertension and AF/flutter, as Pete had mentioned before.

You'll notice that grade ≥3 is less than 3% for hypertension and AF/flutter. Overall, the most common grade ≥3 side effect is neutropenia.

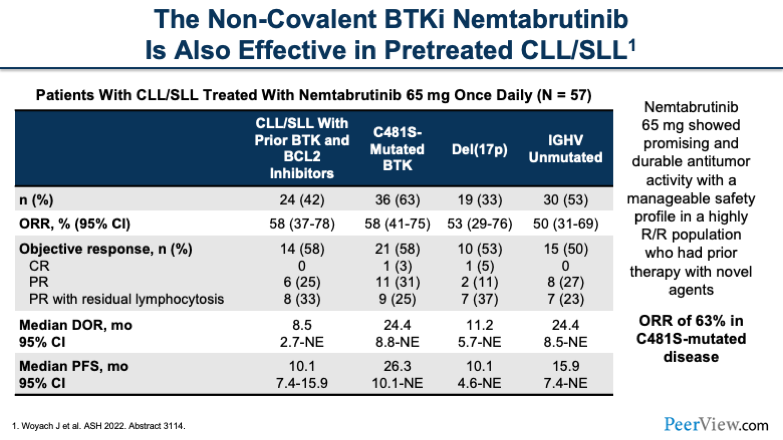

The other non-covalent BTK inhibitor is nemtabrutinib. Nemtabrutinib has also been effective in this heavily treated patient population. The dose for nemtabrutinib was 65 mg. In the table, I'd like to draw your attention to the cells with prior therapy with BTK inhibitors and BCL2 inhibitors and mutational status, and highlight the ORR of 63% in the patients that had the C481 mutation.

And with that, I'll turn it over to Sarah for our next presentation.

Dr. Stump: Thanks, Emily. Now that you all have learned about the current status of BTK inhibitors, both covalent and non-covalent BTK inhibitors, we're going to move on and shift our focus to BCL2 inhibition with venetoclax and touch briefly on combination therapy with BCL2 and BTK inhibitors.

First, I'd like to talk a little bit about venetoclax and where we've come over the last few years. You saw, when Pete was presenting the NCCN guidelines, in addition to BTK inhibitors, venetoclax has a category I recommendation for treatment-naïve CLL and has indication for R/R disease.

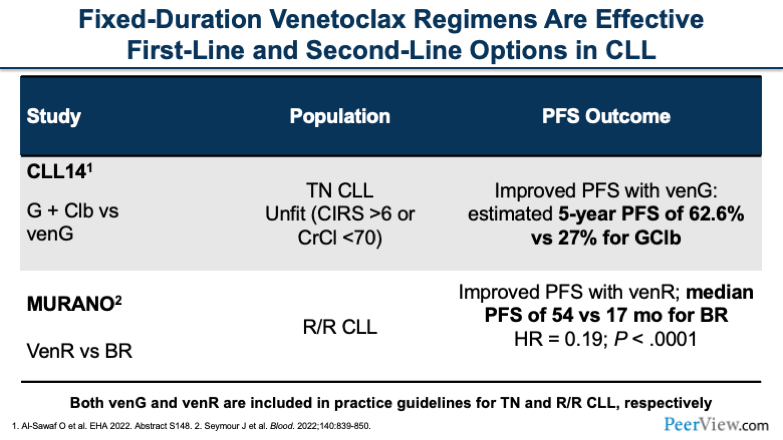

These approvals came from two major studies. The first one I'd like to talk about is CLL14. This was a phase 3 study in treatment-naïve, older patients who were unfit for chemoimmunotherapy, which, believe it or not, at the time, was still standard of care for these patients.

And this study was comparing obinutuzumab (G on this slide) plus chlorambucil with obinutuzumab plus venetoclax. And this was building on the CLL11 study, which established that obinutuzumab and chlorambucil were superior to both chlorambucil alone and chlorambucil plus rituximab.

The CLL14 study, like I said, was basically trying to establish a place in therapy for venetoclax in treatment-naïve patients. And what we saw in CLL14 is that we had a much better progression-free survival with the combination of obinutuzumab plus venetoclax compared with obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil. The estimated 5-year progression-free survival was 63% for the venetoclax arm and 27% for the chlorambucil arm.

This study was definitely practice-changing. It actually came after MURANO, the second study we're going to talk about. The CLL14 study established venetoclax as an option in the treatment-naïve CLL population and as a category I recommendation combined with obinutuzumab.

Fixed-duration venetoclax also has a role in R/R CLL based on the MURANO study. This was another phase 3 study that combined venetoclax with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody—in this case, rituximab—compared with bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) in patients who had been pretreated mostly with chemoimmunotherapy.

And in the MURANO study, we saw very similar results, a major improvement in progression-free survival with venetoclax plus rituximab (venR) compared with BR. The median PFS was 54 months with venR versus 17 months for BR, and that was statistically significant. And again, this was practice-changing at the time and allowed venetoclax to gain FDA-approved indication for R/R disease.

Venetoclax has had an interesting progression in the CLL modern era. It achieved its first FDA-approved indication in 2016 as monotherapy, and it’s been supplanted in combination therapies with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies.

If we're treating someone who is treatment naïve, an option is venetoclax with obinutuzumab. And then, for patients that may have been pretreated with something else and progressed in the R/R setting, we could be using venetoclax in combination with rituximab based on the MURANO study.

An important thing to point out about both of these trials is that these regimens are fixed-duration. When we talk about BTK inhibitors, we're talking about indefinite continuous therapy until progression or unacceptable toxicity. In these fixed-duration therapy studies, patients got 6 months of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and then concurrent venetoclax with a duration of 1 to 2 years.

This was huge for patients with CLL, and it allowed us to have another option other than BTK inhibitors for patients who may not want to be on a medication long term.

Now that we've talked about the established role of venetoclax, both in treatment naïve and R/R CLL, I want to touch briefly on the data we have that's coming out for fixed-duration combinations between BTK inhibitors and BCL2 inhibition with venetoclax.

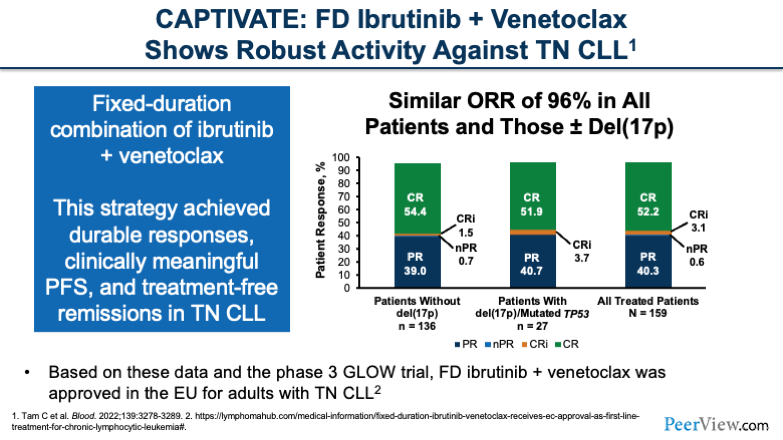

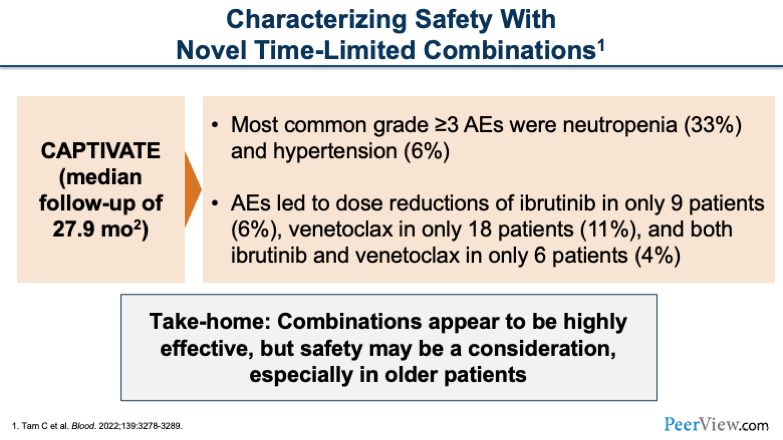

And the first study I want to talk about is CAPTIVATE. This was a phase 2 study combining fixed-duration ibrutinib with venetoclax in treatment-naïve CLL. And this study showed very impressive ORR with 96% of patients having a response to this combination, including patients with high-risk features.

We see that the outcomes of complete response and partial response are basically the same between patients with or without del(17p) and those with mutated TP53. Very impressive results with this study. And we also saw durable responses, clinically meaningful PFS, and treatment-free remissions in this patient population.

Because of this study, we now have a similar phase 3 study called GLOW testing fixed-duration ibrutinib plus venetoclax. This combination is approved in the EU for patients with treatment-naïve CLL and hopefully will be approved in the US soon.

But first, I want to tell you about some safety considerations with the combination of BTK inhibition and BCL2 inhibition. There was a median follow-up of about 28 months, so a good duration of follow-up. And basically, we saw that neutropenia was the most common grade 3 adverse event. When you combine ibrutinib with venetoclax, there are manageable rates of hypertension and cardiac toxicities with the combination as well.

Adverse events led to dose reductions in a manageable number of patients: 6% for ibrutinib dose reductions, 11% for venetoclax dose reductions, and 4% of patients for both drugs.

Our take-homes from the CAPTIVATE study are combinations appear to be highly effective, but we do have some toxicities we have to worry about.

And the other thing I'd like to point out about the ongoing phase 3 GLOW study combining venetoclax with chlorambucil is that in the modern era of CLL, we all kind of agree that the comparator arm is not the best, and we think there are still a lot of questions that we need to answer about combining these drugs up front.

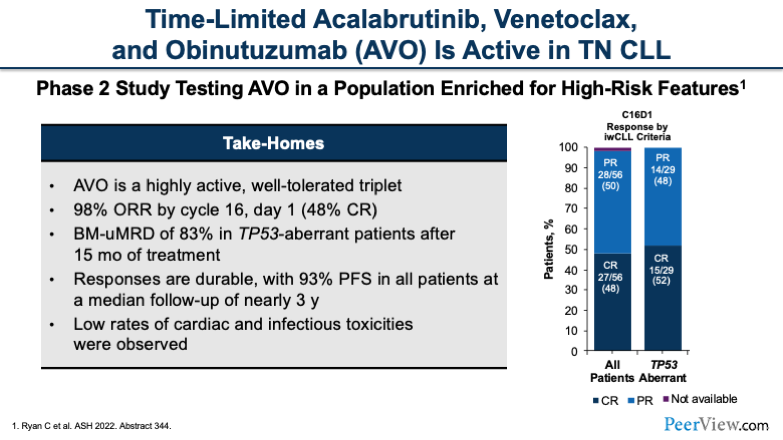

In addition to ibrutinib, we do have some data with second-generation and more selective BTK inhibitors. This study tested the triplet, time-limited regimen acalabrutinib, venetoclax , and obinutuzumab (AVO) in treatment-naïve patients. This is a phase 2 study, and again, we see a really impressive ORR of close to 100%. It is very effective at 98% ORR by cycle 16.

And one thing that we see in these newer studies is MRD-guided durations of therapy. One of the things we worry about, especially in TP53-mutated patients that get venetoclax, is that their duration of response may not be adequate. And one way that we're working to overcome that is to use minimal residual disease (MRD)-guided durations of therapy. You'll see this being a component of a lot of these studies of combinations upfront.

In this study, 83% of patients with TP53 mutations were able to achieve undetectable MRD in the bone marrow after 15 cycles. This was really, really impressive. And we know that MRD translates to longer progression-free survival in patients who receive venetoclax. That is really exciting.

Low rates of cardiac and infectious toxicities were observed in this trial. But again, we don't know at this point that the combination is better than the sum of its parts. So, more to come on that.

Zanubrutinib combined with venetoclax is another second-generation BTK inhibitor that we have data on from the SEQUOIA study. This was a large study of zanubrutinib, and arm D combined zanubrutinib with venetoclax in patients with high-risk features (del[17p]). This arm had very small numbers but also had an impressive ORR of 97%.

There are very exciting combinations emerging with BTK inhibitors and BCL2 inhibition with venetoclax, but unfortunately, again at the current moment, we're not sure if the whole is better than the sum of its parts. So if we give all of these drugs upfront, do we actually extend survival compared with when we give them sequentially? We have to make sure we design future studies to answer that question. I think there’s more to come.

Dr. Stump: And with that, I'd like to pass it back to Pete to talk more about some pharmacy-specific information.

Dr. Campbell: All right. Thank you for that. Now I’ll be talking about dosing, adverse events, and drug interactions. We're at this point now where we have a lot of drugs in our regimen that we can use. They all work really, really well. But the things, especially as pharmacists, that we need to start asking ourselves are, what are the side effect profiles of these drugs, how do we give them, and what other considerations do we need to be thinking about?

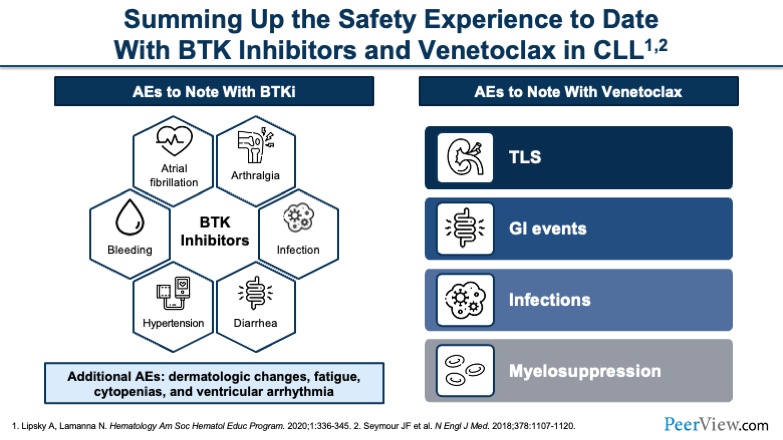

This slide is just a general overview of some of the most common side effects that we can expect with both the BTK inhibitors and venetoclax. You'll see, starting with the BTK inhibitors, very typical things that we anticipate are cardiac effects, such as hypertension and AF. You can also see bleeding. You have to monitor for infections. And less common is arthralgia.

When you move over to venetoclax, you have a very different toxicity profile. First and foremost, I think at the top of everyone's minds is going to be tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). That's something that we are very acutely aware of. You can also see GI events, and then infections and myelosuppression become a risk in certain patients.

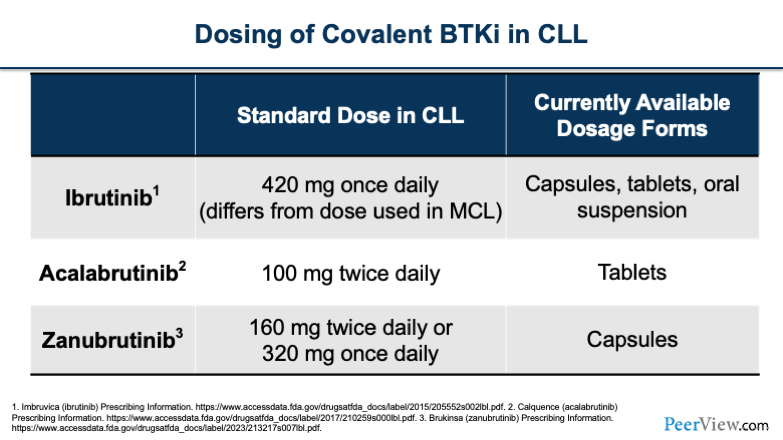

Just to briefly go over the dosing of the covalent BTK inhibitors in the CLL population. Ibrutinib is taken once a day, which is convenient for patients. Acalabrutinib is taken twice daily, which can pose some issues for patients. And zanubrutinib has both a twice-daily and a once-daily option, which also makes it convenient.

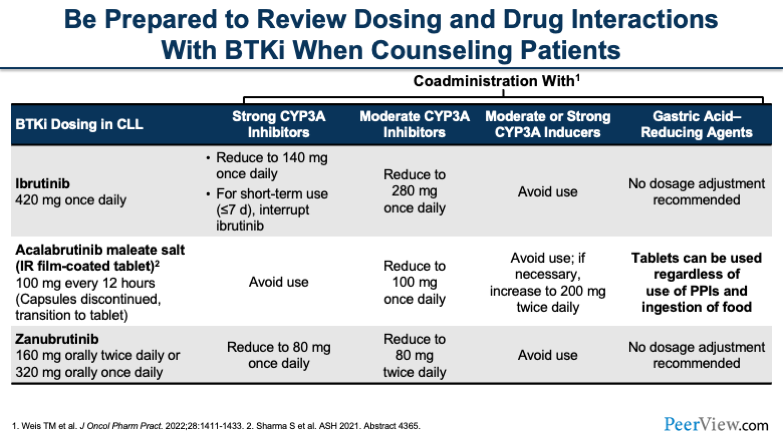

One thing that I think we all have to be acutely aware of, no matter whether you're a physician, a pharmacist, or an NP, are the drug–drug interactions that all of these drugs carry. I think when I talk to residents or students about TKIs or BTK inhibitors, it's drug interactions, drug interactions, drug interactions. It's something that we need to think about all the time.

You'll see here that all of these drugs have interactions with CYP3A, and they have a various number of ways in which you can handle them. For ibrutinib, if you're using a strong CYP3A inhibitor, you'd want to reduce the dose. Or if it's only going to be for a short period of time, you can think about interrupting the dose for less than a week or so. For acalabrutinib, you'd want to try to avoid it if at all possible. And for zanubrutinib, you'd reduce to 80 mg once a day.

Now, the other thing that you have to keep in mind, going back to the duration of therapy, you'll see that a lot of the strong CYP3A inhibitors that these patients end up on are long-term therapies. Very infrequently is it that you're putting someone on a strong CYP3A inhibitor for a handful of days. You have to keep this in mind because, over time, these are going to become permanent drug interactions if you're putting patients on, say, an azole antifungal for a prolonged period of time.

The other thing to keep in mind is when you're using CYP3A inducers, you generally want to avoid these BTK inhibitors. And then the last thing to think about is gastric acid-reducing agents. We don't really have to consider this as much anymore with the newer formulations that we have, while historically this was an issue.

Challenge Question

Assume you are managing a patient with TN CLL/SLL preparing to start therapy with acalabrutinib; the patient is currently on therapy with PPIs. What dosing strategy would you use for this patient?

- I’m not sure

- Acalabrutinib capsules; no need for dose adjustments

- Acalabrutinib capsules; reduce dose to 100 mg daily

- Acalabrutinib tablets; no need for dose adjustments

- Acalabrutinib tablets; reduce dose to 100 mg daily

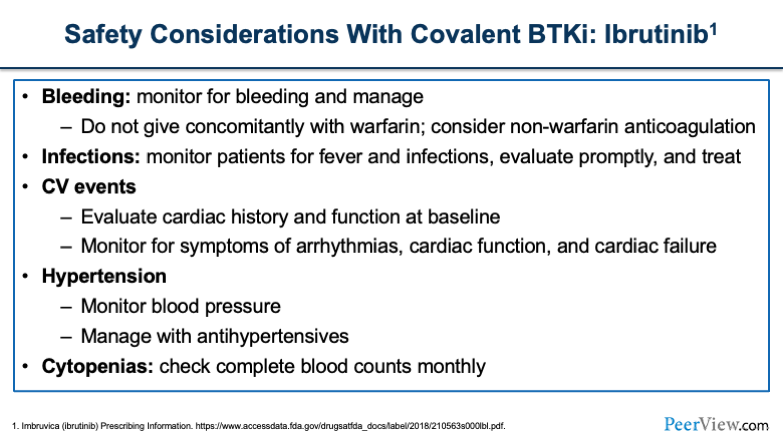

For other safety considerations, we'll start with ibrutinib. Bleeding is something that I think we all have at the top of our minds. It was drilled into us when we first learned about ibrutinib. For patients who are undergoing any sort of major or minor procedure, you want to think about holding ibrutinib for different lengths of time, for instance, 3 days for a minor procedure and a week prior for any larger procedure.

Infections are something you'll want to think about. The cardiac events that we've talked about with all of these agents, hypertension and cytopenias, which you want to check blood counts monthly in these patients.

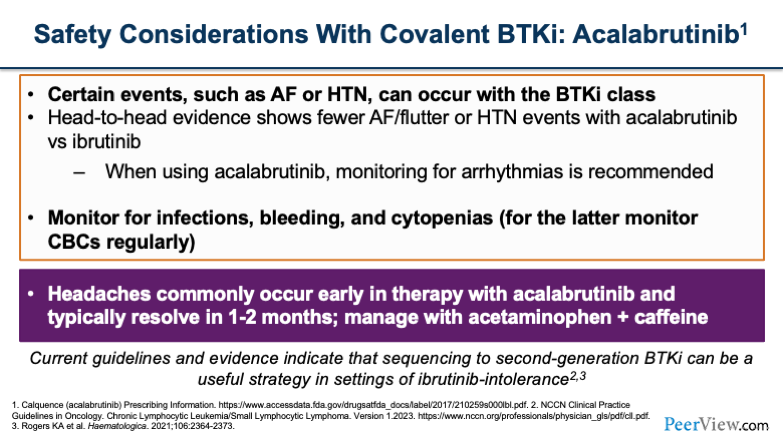

Now you'll see, as we go over the next two slides, there are a lot of similarities between acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib. You still see some of the cardiac side effects, although they're less frequent than we saw with ibrutinib, as we've gone over with some of the previous data. And the thing that sets acalabrutinib apart are headaches that can occur in these patients, which is a unique toxicity compared with the other agents.

Headaches usually occur early on in therapy and, within the first 1 to 2 months are self-limiting. You can manage headaches in most patients with acetaminophen or caffeine supplementation.

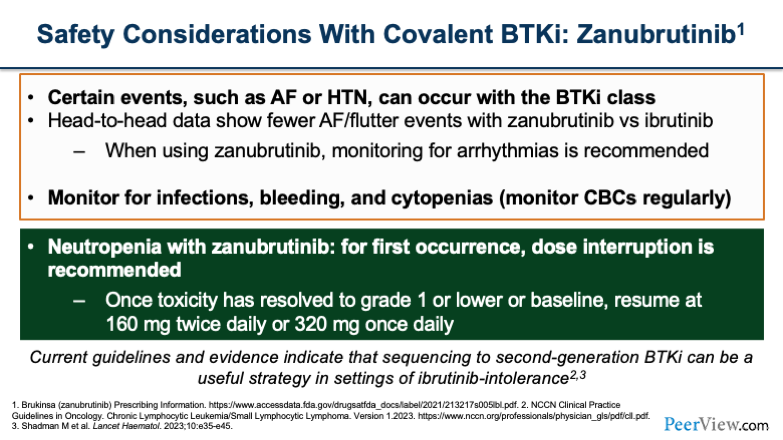

Now, when you switch over to zanubrutinib, you'll notice the top portion of the slide is the same because we still worry about those cardiac side effects, as well as infections and bleeding. The thing that's a little bit different and more prevalent with zanubrutinib is, the neutropenia that you may see. What we typically do to manage neutropenia is at the first occurrence, we would interrupt the dose and wait for the patient's counts to recover. Once it gets to grade 1 or baseline, we resume at 160 mg twice a day or 320 mg once daily.

It gets a little bit more complicated once you have repeat occurrences of neutropenia, and that’s when you have to think about further dose reductions or potentially switching to a different agent.

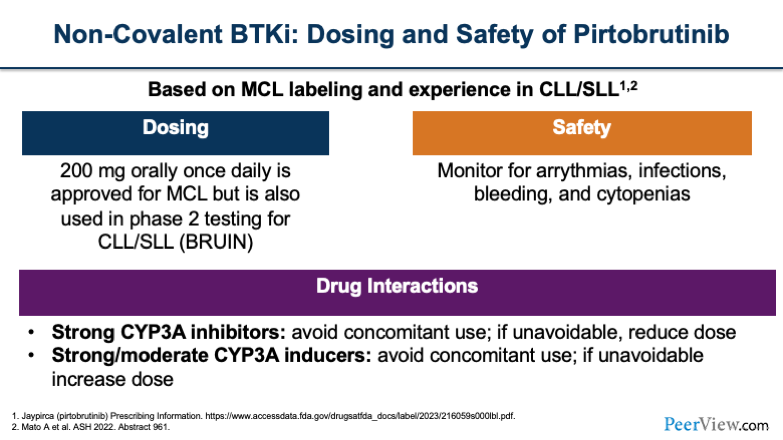

Now, when we look at our non-covalent agents, such as pirtobrutinib, based on the MCL labeling and some of the experience in CLL, the dosing is 200 mg once daily, which is what's being used in the BRUIN study. You'll want to monitor patients for arrhythmias, infections, bleeding, and cytopenias, which are the typical class effects of BTK inhibitors. Also, pirtobrutinib carries some of those same drug interactions, such as you want to think about avoiding use, if possible, with strong CYP3A inhibitors.

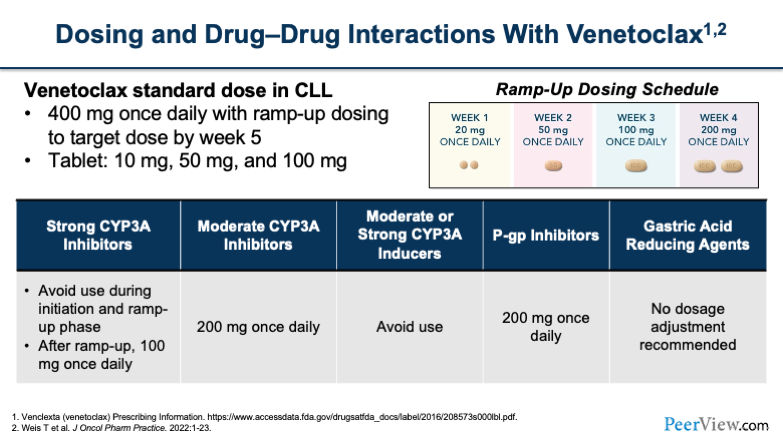

Now, shifting to venetoclax, we talked about TLS earlier, and that's part of the driver behind why we have such an interesting dosing schedule with venetoclax when we first start using it. I think a lot of people are probably accustomed to ramping up the dose in these patients.

You'll notice that, while ultimately, you're looking to get to 400 mg once daily, you have to do that slowly in most patients by ramping the dosing up to avoid TLS. In week 1, you would start at 20 mg once a day and then go up to 50 mg, 100 mg, and 200 mg over the subsequent 4 weeks.

You also want to think about dose reductions for these patients if they're on strong CYP3A inhibitors. And the one thing that I would note is, if a patient is on a strong CYP3A inhibitor at baseline, you're going to approach your ramp-up dosing a little differently. You'll notice here on the slide, it says after ramp up, you can do 100 mg once daily. There are different treatment strategies that you can use, whereas you can also do a slow ramp up and cap it at 100 mg.

I think that's probably the approach that most people would take, rather than ramping them up to 400 mg and then putting them on the strong CYP3A inhibitor and then dropping them back down to 100, which is not as logical of an approach, especially because a lot of these patients are on the strong CYP3A inhibitors for a prolonged duration.

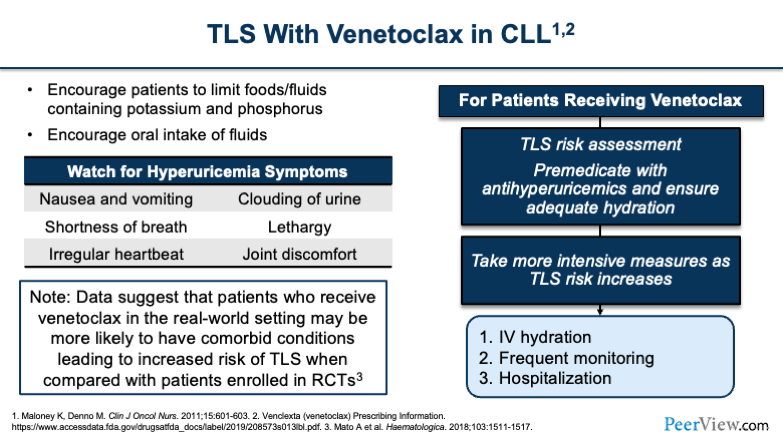

Now, TLS is at the top of our minds with venetoclax. And so, when you're thinking about venetoclax, the first thing you have to do is assess the patient’s risk. You have to determine whether they're high or low risk for TLS, because that's going to differentiate how you manage them, especially when deciding whether you do the ramp-up dosing as an outpatient or as an inpatient to monitor for TLS. It can also influence whether or not you do a rapid escalation, which some institutions have started to do, so that they don't have to prolong hospitalizations or prolong the dose escalation over the full 4- to 5-week period.

You'll want to tell patients what to watch for when monitoring for hyperuricemia symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, clouding of the urine, and joint discomfort. It's important to counsel patients on these things, especially, if they're doing the dose escalation at home. They're going to be the ones who notice these effects before anyone else, and they're going to have to let you know, because that's when you're going to want to bring them in for evaluation.

And the other thing to keep in mind—I'll draw your attention to the box in the lower left of the slide—is how important it is to take a very close look at patients from a risk assessment standpoint because, even though we saw really high rates of TLS in clinical trials, remember that a lot of patients that are in clinical trials are more of your pristine patients. They have better renal function.

And so the real-world population may be at an even higher risk of TLS compared with what we saw in the clinical trials, and so that's why it's really important that we take a very close look when we're first assessing patients and deciding how we're going to do the dose escalation strategy.

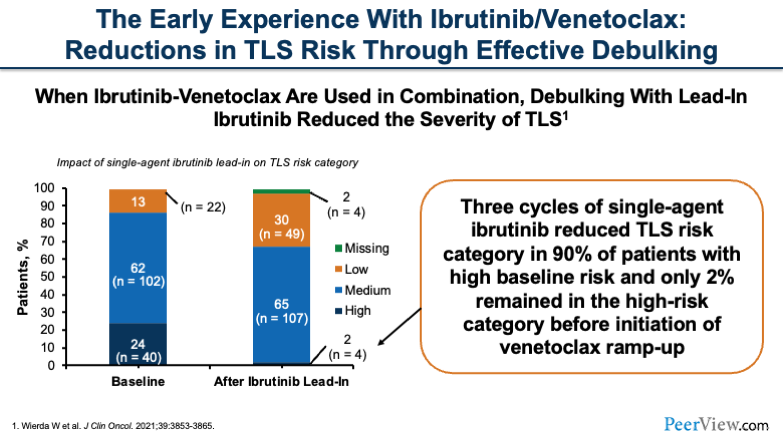

Now, if we look at the early experience with ibrutinib and venetoclax together, what we can think about is, "Okay, we now have multiple drugs that work really well. Is TLS going to be even more of a risk?" Well, it turns out that, when you're using this combination together, if you do a lead-in debulking with ibrutinib, you can actually reduce the severity of TLS in these patients.

What you can see here are, three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib prior to initiating the combination therapy significantly reduced the risk and severity of TLS in these patients. This lead-in strategy is pretty effective in debulking patients, so that when you initiate the venetoclax, they don't have as much tumor lysis.

Challenge Question

Test your skills: What strategy would you select to help reduce the incidence of TLS when managing a patient with CLL who is preparing to receive a ibrutinib + venetoclax combination?

- I’m not sure

- Use flat venetoclax dosing instead of ramp-up

- Lead-in ibrutinib (3 cycles)

- Add ibrutinib after venetoclax ramp-up

- Use reduced-dose ibrutinib

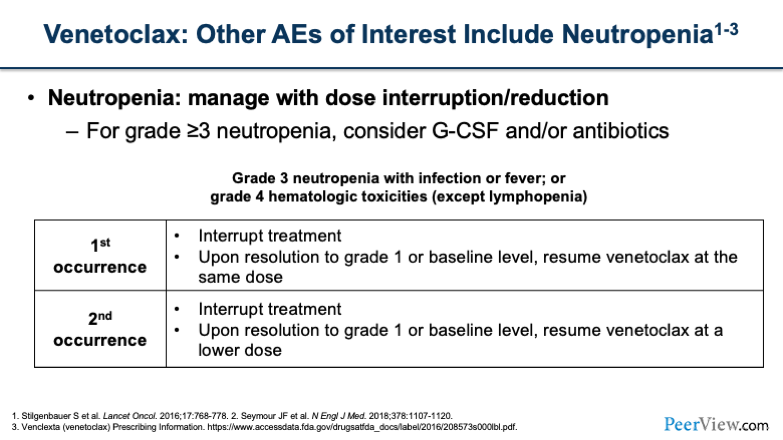

Another thing to keep in mind is neutropenia with venetoclax. You'll want to think about managing neutropenia with dose interruptions or reductions, similar to what we talked about before. For grade >3, this is when you want to think about using G-CSF or antibiotics for either neutropenic fever prophylaxis or in the event of an actual infection.

For the first occurrence of grade >3 neutropenia, you would interrupt treatment. When it returns to grade 1 or baseline, resume at the same dose. For the second occurrence, you'd want to interrupt treatment and then resume at a lower dose. I think you have to think about the severity and depth of the neutropenia that the patient experiences when you're deciding what dose to resume at.

Some people will do a dose decrease from 400 mg to 300 mg. If you have a patient who has more severe or more prolonged neutropenia, you may want to consider going from 400 mg down to 200 mg. And remember, you can always go back up if the patient tolerates it.

Dr. Campbell: And with that, I will pass it back over to Emily.

Dr. Dotson: Thank you, Pete. Now we're going to dive into a few cases to really explore the role of the pharmacist in this setting.

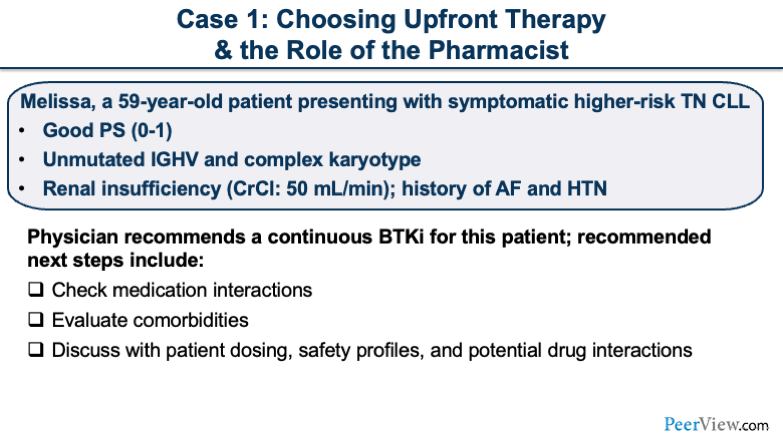

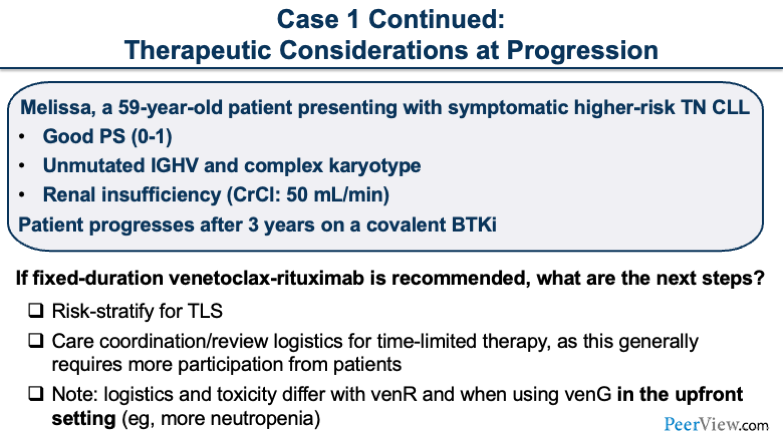

Dr. Dotson: Our first case is regarding choosing upfront therapy. Melissa is a 59-year-old patient presenting with symptomatic higher-risk treatment-naïve CLL. She has a good performance status, and she has unmutated IGHV and a complex karyotype. She does have renal insufficiency. Her creatinine clearance is provided, as well as a past medical history of AF and hypertension.

This first case I'll pose to Pete. In terms of a physician recommending a continuous BTK inhibitor for this patient, what steps should we consider as pharmacists?

Dr. Campbell: Sure. I think that this is a patient who an upfront BTK inhibitor makes a lot of sense, but there are a handful of things to consider before we choose which BTK inhibitor to use. We'd want to make sure that we have the patient's whole past medical history as well as know all of the medications that they're on. That's going to come in key when you're looking at drug–drug interactions. Also, pharmacists play a huge role in patient access and patient support in terms of actually obtaining the drug.

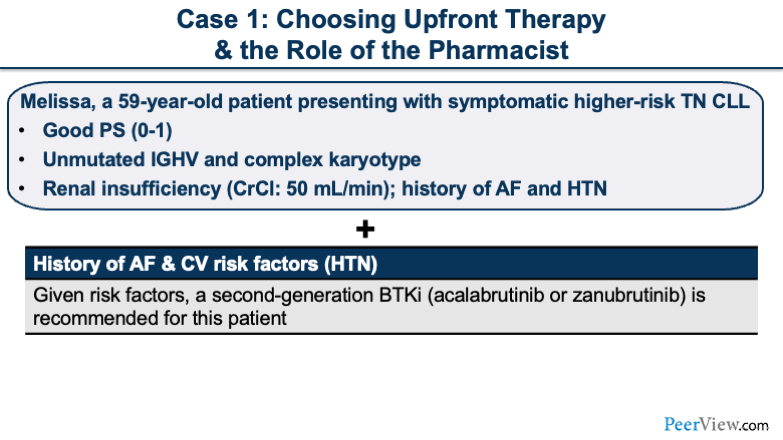

Now, when actually choosing the BTK inhibitor, we're thinking right now of ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib. When we look at Melissa's past medical history, we see that she has a history of AF and hypertension. And so, in a patient that already has an underlying cardiac history, I think this is the perfect scenario in which I would want to potentially move away from ibrutinib. And I think I'd be more inclined to use zanubrutinib or acalabrutinib in this patient rather than giving the patient a drug like ibrutinib, when you already know that they have a history of AF.

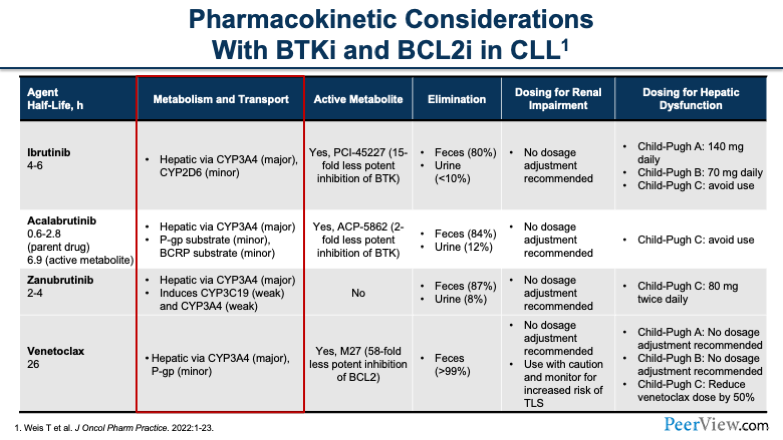

Dr. Dotson: Makes sense. Just to tie in some of that information, as we're looking at drug interactions for this patient and really trying to consider some of the pharmacokinetic considerations, I'd like to call your attention to some of the metabolism that we see with the BTK inhibitors. We would be looking at medications that were hepatically metabolized, specifically through the CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 enzyme systems.

Just to recap what Pete mentioned, looking at those medications and what comorbidities Melissa has is important, as well as discussing dosing and the safety considerations with her.

Given her cardiovascular risk factors of AF and hypertension, a second-generation BTK inhibitor, such as acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, is recommended for this patient.

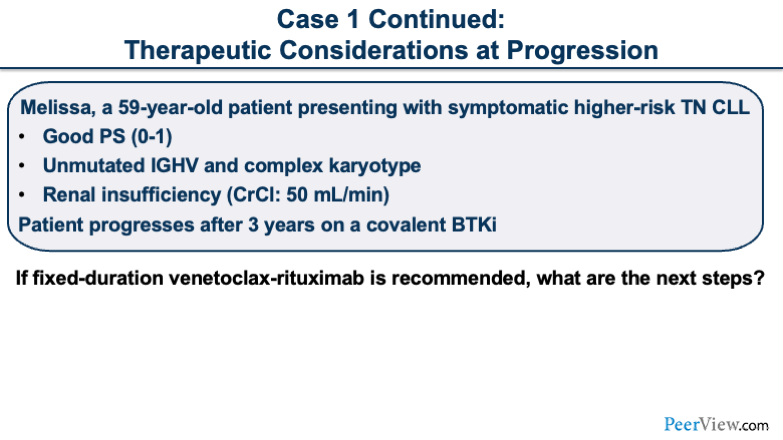

Melissa started her therapy on a second-generation covalent BTK inhibitor, and we are now fast-forwarding to 3 years later when she is progressing on her treatment. What are the next steps if her next treatment recommendation is the fixed-duration venetoclax-rituximab regimen? And I'll pose this question to Sarah.

Dr. Stump: Yeah, I think this is definitely a real-life scenario, where a patient received BTK inhibitor therapy upfront, they've progressed after 3 years of treatment, and a venetoclax-rituximab recommendation makes a lot of sense. We have an FDA-approved indication for this type of patient, so it makes sense. Similar to Pete's case, starting on a new medication, obviously, knowing the patient’s other medications is important. I'm sure her meds have changed in 3 years. I want to know what she's taking now. We still have to worry about drug–drug interactions when we think about venetoclax.

Obviously, for venetoclax, TLS risk assessment is important. I want to know her absolute lymphocyte count and how bulky her disease is, which are the two main components that go into our TLS risk assessment. We don't have that information provided to us, so that would be something I'd be looking to obtain.

And then the other thing that's interesting is her renal insufficiency. I'd like to know how that has changed over the last 3 years as well. Renal insufficiency and creatinine clearance are not part of the risk assessment in the package labeling per se. But what we've seen with a lot of real-world TLS studies is that elderly patients or those with renal insufficiency may be more likely to experience TLS, which kind of makes sense.

It'd be interesting to know what her kidneys are doing now and if she is at high risk or low risk for TLS, which would determine if we would admit her as an inpatient or outpatient to administer the venR regimen. At our institution, we ramp up all venetoclax regimens as an outpatient, so I would prepare the patient for that.

There is some patient buy in that you have to get when asking a patient to come in once a week for ramp up dosing. For high-risk patients, you would actually check labs on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16, and so on. I would spend some time talking through those logistics with her.

The other thing that's exciting to tell this patient is that this is a fixed-duration treatment, which is unlike her first-line therapy. This isn't an infinite outlook, which is different than what we counseled her on BTK inhibitors; and hopefully, fixed-duration venetoclax-rituximab should be exciting to the patient in that they get to see the end of the tunnel early on. I'll also counsel them on drug interactions, TLS risk assessment, and the logistics of the therapy.

Dr. Campbell: Yeah, I would just add one thing to that. I think in terms of counseling, you had a really good point in getting patient buy in, because when you're doing this as an outpatient, the one really important thing from a TLS standpoint is that the patient maintains hydration, which can be very hard to get patients to commit to. I know how many people have probably had seven cups of coffee and no water today; and that's going to be the same case for your patients. You will have to convince them to make sure that they adhere to these things, like staying hydrated.

Dr. Dotson: That's a great point. We really want to dive into stratifying the appropriate patients for inpatient and outpatient and talking through the care coordination for the venetoclax-rituximab combination is very important. Also, communicating the toxicity concerns and the logistics is a little different in this time frame for the R/R setting versus if the patient would have had a fixed-duration with venetoclax and obinutuzumab.

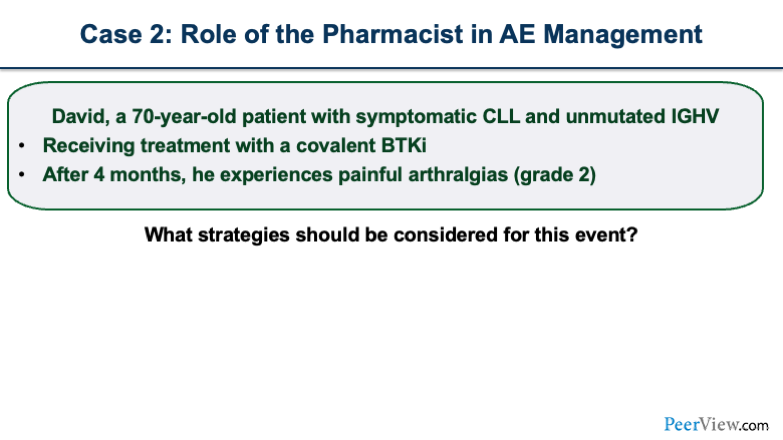

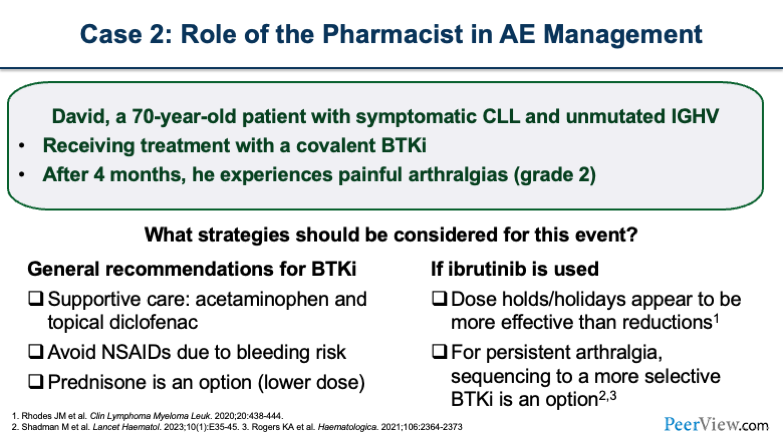

Dr. Dotson: Our second case explores the role of the pharmacist in the management of adverse events. David is a 70-year-old patient with symptomatic CLL. He has unmutated IGHV, and he has been receiving treatment with a covalent BTK inhibitor for about 4 months. He is now experiencing painful arthralgias that are grade 2 in severity. So back to Pete, what strategies should be considered for this event?

Dr. Campbell: Yeah, arthralgias are an interesting toxicity with the BTK inhibitors, because we run across people who will say, "I've never seen this," and then we run across people who say, "Oh, I see this all the time." But it's something that patients suffering from arthralgias feel every day, and they wake up with painful joints.

I think that the first thing that you want to think about is, how can you treat the arthralgias? And you want to look short-term and the long-term solutions. When you first start thinking about the short term, you want to ask if you can use acetaminophen in these patients and/or would you use an NSAID?

I think a lot of us would probably shy away from using NSAIDs, given the bleeding risk that's prevalent with the BTK inhibitors. And I think this is something that you need to have a conversation with the patient about, because people are all too likely to self-medicate and take NSAIDs for prolonged periods of time without telling anyone, which really sets patients up for a potential bleeding risk.

In the short run, you can give patients supportive care with medications, but there are some data that show potential benefit from a dose reduction or a dose holiday, especially with ibrutinib. In some patients, you can stop the drug for a period of time and the arthralgia will resolve, then when you reinitiate the drug, the arthralgia doesn’t recur.

If the arthralgia does recur after a dose holiday, you would want to think about dose reduction or potentially switching to another BTK inhibitor or another therapy altogether, depending on how severe the arthralgia is for the patient.

Dr. Dotson: Great. Some important information. As Pete mentioned, avoid NSAIDs due to that bleeding risk, and then, if the patient is on ibrutinib, dose holding. And it is very different from each BTK inhibitor, so really trying to make it patient-specific.

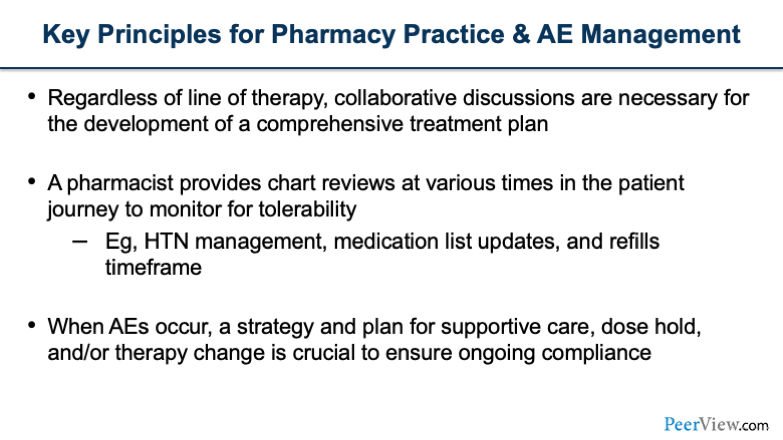

Some take-home points are regardless of line of therapy, collaborative discussions are necessary for the development of a comprehensive treatment plan. The pharmacist can play a crucial role in chart reviews at various times in the patient history. We know that hypertension management may be necessary. Medication list updates, as Sarah alluded to, as patients are on treatment. It's important to ask what their updates are with each visit, as well as looking at their refills and making sure that those are on time.

And then, when adverse events occur, a strategy and a plan are helpful in terms of compliance, making sure the patient feels supported, whether they need a dose hold or a therapy change, and making sure that compliance is ongoing.

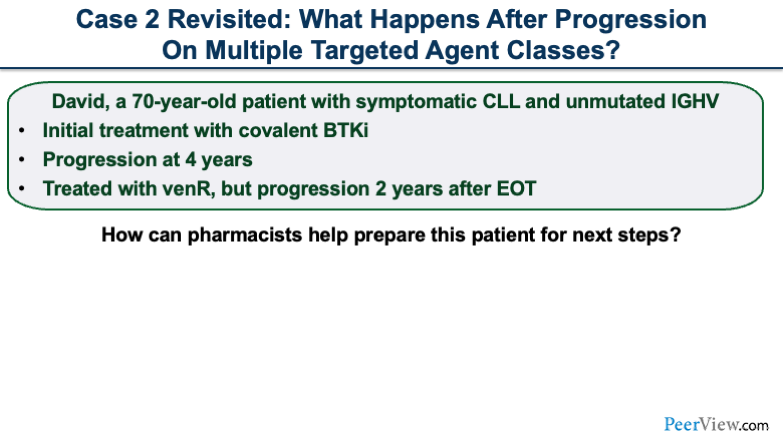

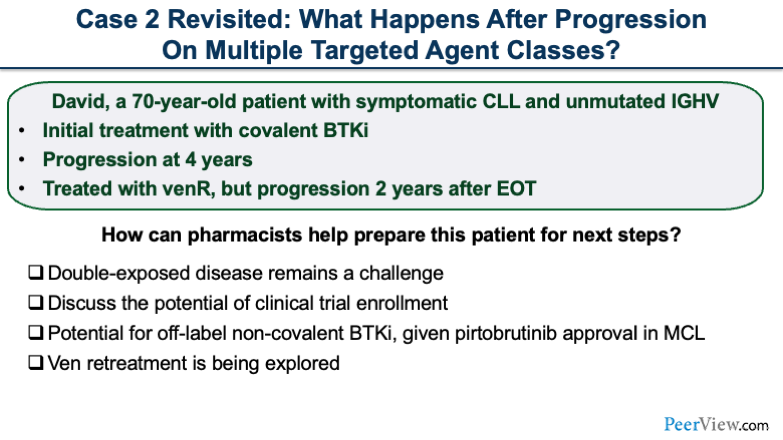

Revisiting our second case, David has now progressed after 4 years of therapy. Just as a reminder, his initial treatment was a covalent BTK inhibitor, and then he was treated with venR, but progression occurred 2 years after the end of treatment.

The question now is, how can pharmacists help prepare patients for this next step in treatment? Sarah, do you have experience with this?

Dr. Stump: Yeah. Again, I think in the modern era, this is coming up more and more, where patients have been exposed to both BTK inhibitors and BCL2 inhibition and, unfortunately, have progression. The first thing that comes to my mind is, can we find a clinical trial that's appropriate for this patient? That is, I think, always going to be where we go for double-exposed patients.

There are a lot of options out there, and we talked about non-covalent BTK inhibitors, which, for now, are not FDA approved. But we can be successful in getting pirtobrutinib off label. That could be a good possibility for a non-covalent BTK inhibitor for this patient.

We do have some information about retreatment. This patient received venetoclax-rituximab in the R/R setting, completed the fixed-duration therapy, and progressed 2 years later. There are some data supporting venetoclax-anti–CD20 combination retreatment. Those studies are small in number, but they have impressive results if the patient had an initial response to therapy.

And then the other thing I would be thinking about is, which we alluded to earlier, if you pursue retreatment, perhaps doing that on a clinical trial would give the potential for MRD-guided duration of therapy for this patient.

Dr. Stump: We have a few options, including off-label options. I’m always wondering what clinical trial options we have for patients, and we have some emerging data on retreating patients with fixed-duration venetoclax after progression.

Dr. Dotson: Great. In this setting, where patients have that double exposure, and thinking about some of the data that were presented earlier with the BRUIN trial, as well as thinking about venetoclax retreatment, we want to make sure we are really honing in on clinical trial inclusion for our patients.

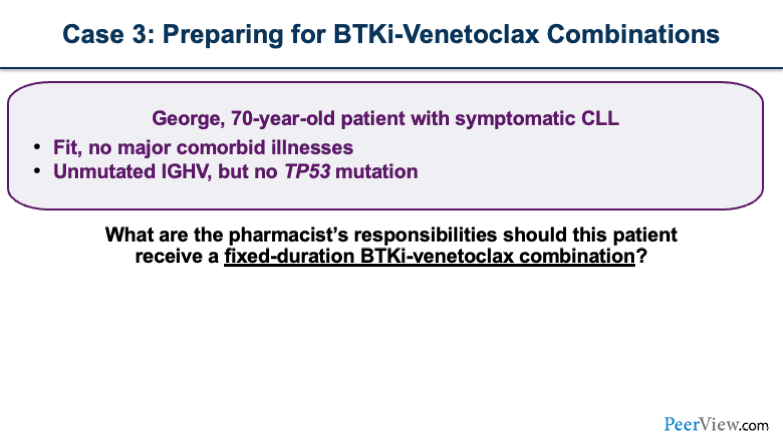

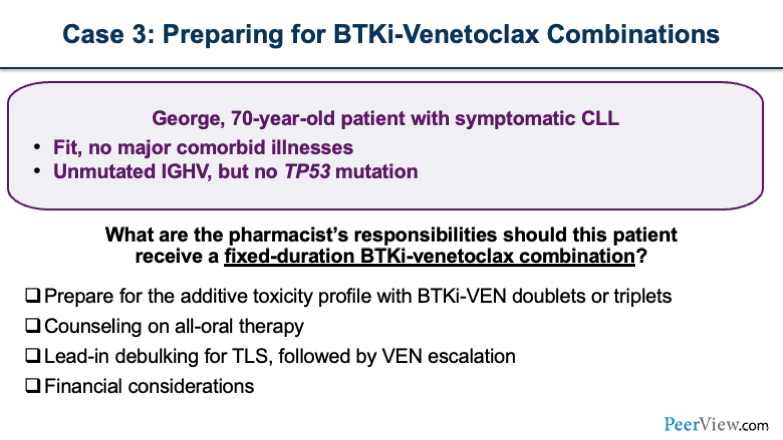

Our third case is preparing for a BTK inhibitor combination with venetoclax. George is a fit 70-year-old patient with symptomatic CLL and has unmutated IGHV. He has no major comorbid illnesses and no TP53 mutation. What are the pharmacist's responsibilities if this patient is to receive a fixed-duration BTK inhibitor with a combination of venetoclax? Pete, Sarah, any thoughts here?

Dr. Campbell: I think that there are a lot of things you need to think about here. First and foremost, the thing that comes to mind is toxicity when you're talking about using a BTK inhibitor and venetoclax, especially increased risk of neutropenia. You need closely monitor these patients, at least initially, because, when we're talking about adding all of these different treatment regimens, yes, there are really good outcomes, but the toxicities appear to be additive.

The other thing to think about is when you're adding these therapies together, you're also talking about financial toxicity for some patients. Where each of these drugs individually tends to be expensive, now you're talking about multiple oral agents with high copays. This could potentially start to snowball. And so I think patients need to be prepared for that.

Dr. Stump: Yeah, absolutely. Another thing that I'm thinking about is talking to the patient again about logistics. When we combine BTK inhibitors with venetoclax, we're usually doing the BTK inhibitor lead-in. Usually, patients get two to three cycles of 2 to 3 months of BTK inhibitor monotherapy. And we do see that is an effective debulking strategy, like Pete showed earlier.

If someone were at high risk for TLS at baseline, these studies actually give us the luxury of reassessing their TLS risk. We don't do this in clinical practice a lot. After you give a few doses of obinutuzumab, we're not repeating CT scans or seeing how big their nodes are. We're just doing a physical exam.

But in this case, we're debulking a lot of these patients with BTK inhibitor monotherapy. When I initiate venetoclax, I might be less concerned about TLS, which may be helpful for this patient, who's a little older. We don't have all of his labs and his renal function, but we presume it's probably pretty good if he's fit with no major comorbidities.

But that's another thing I just want to be thinking about for combination therapy, how is that going to look with the lead-in of ibrutinib? We need to make sure the patient tolerates ibrutinib and gets through the first few months before we add in another therapy with unique toxicities and counseling points.

Dr. Campbell: Yeah. I think, lastly, compliance can also start to become an issue. There are plenty of studies across the entire pharmacy spectrum that show that compliance can be pretty poor, regardless of what drug you're talking about. And the benefit of fixed duration is that you're not talking about forever.

But these are multiple medications that could have side effects, and you really need to harp on patients that compliance is really important, especially, depending on which BTK inhibitor you're talking about, the dosing schemes, and so it can be more complex than just taking one oral therapy. Compliance should be something you talk to patients about.

Dr. Dotson: Great information. Specifically, even thinking about that these are two oral medications, we've talked a lot about those combinations where patients are coming into the hospital. And so keeping in mind that oral therapies keep patients out of the hospital, but it's equally important to have those phone call follow-ups, making sure patients are aware of all the counseling that they need in terms of starting this treatment.

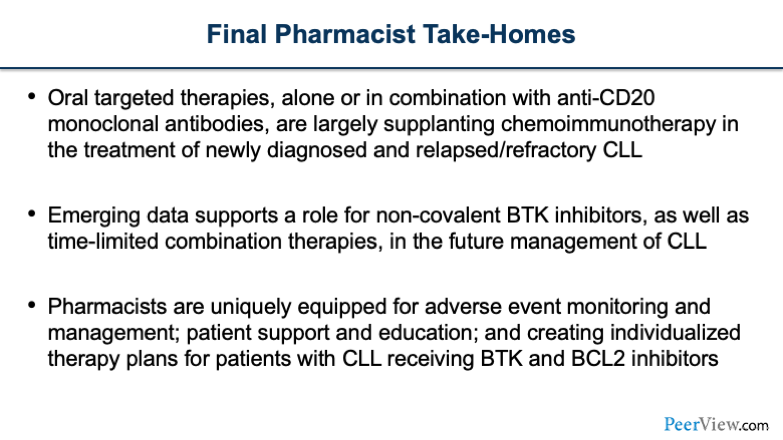

And then just some final take-homes. Oral targeted therapies, alone or in combination, are largely supplanting chemoimmunotherapy in the treatment of newly diagnosed and refractory CLL. We have emerging data that support a role for non-covalent BTK inhibitors, as well as some time-limited combination therapies. And there’s more to come in the future management of CLL.

We feel like pharmacists are uniquely equipped for adverse event monitoring. We've described some tools in terms of managing arthralgia, patient support and education, and creating individualized therapy plans for patients that are receiving both BTK inhibitors and BCL2 inhibitors or those in combination.

Dr. Stump: And with that, we’ll answer some questions from our peers. Our first question: Do you modify the ibrutinib dose when combining with venetoclax? The answer is no. The target dose of ibrutinib is still the same. Like I mentioned before, there is a lead-in, so you would start on 420 mg of ibrutinib for two to three cycles, depending on which study you're looking at. We do the same ramp-up dosing for venetoclax: 20 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, and 400 mg. So, the same dosing strategies. We just use that lead-in debulking before we start the venetoclax ramp up.

Dr. Campbell: Yeah, I think another question that is pertinent, because it comes up a lot, What is the role for antimicrobial prophylaxis when using venetoclax? I think that this is something that you have to look at each individual patient and assess their risk for the incidence of neutropenia. In a lot of patients, if they do experience neutropenia, it will be periodic, where they won't have prolonged neutropenia throughout the entire course of being on venetoclax.

And so maybe for those select periods of time, you would think about putting them on antimicrobial prophylaxis. But I think what I would generally avoid is putting people on antimicrobial prophylaxis throughout the entire duration of venetoclax therapy, which could be a very long time.

You know, these are patients who are going to get infections over time. You probably want to decrease their systematic exposure to antibiotics as much as you can, and there's really no need for continuous antimicrobial prophylaxis. Think about saving it only for when they actually become neutropenic.

Dr. Dotson: Yeah.

Dr. Stump: Another good question: Have acalabrutinib capsules been fully discontinued? And for patients who have been on capsules, can you immediately transition to the newly available formulation of tablets?

This is huge, because acalabrutinib used to be available only in capsule form, which interacted with acid suppressants. Patients could not be on a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and be on acalabrutinib, which actually really changed how we looked at patients for treatment-naïve upfront therapy if they were on a PPI.

Now we have acalabrutinib tablets, which don't have that same interaction, and capsules are being phased out. I think the last time I asked our specialty pharmacy; we still had some capsules lying around. So be careful before you put someone on tablets, and know what your pharmacy is sending patients.

This is really good advancement in just formulation. It's really important to keep in mind, that we can now put patients on acalabrutinib who are taking PPIs, because we can give them tablets. And you can immediately change over. There's no need to wait.

Dr. Dotson: Great. Another question: What if the first step in managing AF on ibrutinib, do we treat it first or do we switch agents? If this is a newly diagnosed AF, those are quite tricky. You have to think about a couple of things in terms of whether or not they also require some anticoagulation because of the new diagnosis. Weighing the risk versus benefit of what type of supportive care agents they may need to be on, as well as drug interactions is very important. Keep in mind, when you start some of these agents, they do interact with the BTK inhibitors. But that first step ideally would be finding an agent that would help control the AF.

I will say, we are very quick to switch therapy if there’s an interaction or if there’s an excessive bleeding risk when we're adding an anticoagulation to treatment.

So keeping in mind, you can keep patients on therapy and support them, but also know you have the option for dose adjustments when needed for drug interactions, or alternatively, switching therapy.

Dr. Campbell: Another interesting question: Historically, there are a lot of patients who can't tolerate CLL therapy. Do you run into that with these new options?

Certainly, there are patients who can't tolerate various therapies, but I think maybe the big take-home point of this entire presentation is that we have moved past the era of chemoimmunotherapy. And when we think about patients not being able to tolerate therapies in CLL, that's really what we're talking about. We're talking about giving chemoimmunotherapy and how rough it was for a lot of patients.

We don't just have a BTK inhibitor. We have multiple BTK inhibitors. And I think that while a lot of patients tolerate most of these drugs, in the event that you do need to switch, you have a lot of different treatment options. I think it's very rare, if not at all, that you'd run across a patient anymore that you don't have treatment options from a tolerability standpoint. You can always move them between BTK inhibitors based on different toxicity profiles, and BTK inhibitors are used in so many different combinations now that I think you have a lot of different treatment strategies.

Dr. Stump: Yeah. And even before we had second-generation BTK inhibitors, we had a lot of success dose-reducing ibrutinib, while having really long-term progression-free survival. I think we have the luxury of new agents and new options. But the old school is also great.

Another question: Have you ever given venetoclax-obinutuzumab in R/R instead of venR? Obviously, that would be off label because the obinutuzumab is approved upfront. But if you give a BTK inhibitor upfront and now you've relapsed, most physicians are going to want obinutuzumab. They're going to want venetoclax-obinutuzumab even in R/R settings.

So we do talk to payers about that, and we sometimes have to support our rationale. But for the most part, we have had good success getting venetoclax-obinutuzumab, even in the R/R setting. Occasionally, we have some barriers where we would have to use venR, but that is a question that comes up a ton in clinic.

Dr. Dotson: In particular, those patients who may not necessarily have tolerated the rituximab component may need to switch to a different monoclonal antibody.

Another question: How often should we be monitoring patients when they are on a continuous BTK inhibitor? So, early on, when they start, a lot of patients are receiving care through telephone follow-up, and we have patients come in for their labs to make sure that we're monitoring those as they start. And that's really unique with a BTK inhibitor, that we see the lymphocytosis that could occur.

And counseling patients when they get those labs back is equally important to make sure that they're not caught off guard when they see that rise in white blood cell count. So upfront monitoring is important. And then, as patients are on treatment, typically you can span that out to every 3 to 6 months, depending on how often their follow-up is specifically for their disease.

But a lot of those toxicities do dissipate over time. There are a few, such as hypertension with ibrutinib, that can be more of a sustained adverse event.

Dr. Campbell: Yeah, and I think this is where you really drive home the importance of telehealth, being able to get local labs if you're a large referral center, and your patients may live 100-150 miles away. They're not trekking to see you every month, probably, and so having the ability to get local labs and see them via telehealth is really important.

One more question: "Could you comment on the role of mutation testing in patients responding to therapy and if progression is suspected?"

I think that this is an interesting question, because, with our newer agents specifically targeting different mutations, this is something that I think will become more prevalent. But I'm not really sure at this point in time, because a lot of these drugs are being used in a clinical trial setting. How realistic is it in the normal, nonclinical trial patients to be doing mutation testing? I'm wondering if you guys have any additional thoughts on that.

Dr. Stump: I would agree. I don't think it's happening routinely in most practices. The reality is, if you progress on a BTK inhibitor, you would likely be thinking about non-covalent options anyway. I don't think that mutation testing is currently standard of care. It would be done at large academic centers that have trials open and are looking at mutation testing.

We have some interesting data coming out about specific mutations, specifically with venetoclax. We see that patients with high-risk features and certain mutations don't have durable responses to venetoclax. We're learning a lot more about that, but I wouldn't say that it's currently part of our standard of care.

Dr. Dotson: Yeah. We are doing some testing at a year mark, just to do a pulse check to see where patients might be in terms of their mutational status. There are some data to support that patients may not necessarily progress as soon as they have that mutation, so we are really trying to hone in on what the next step might be a number of months down the line before that mutation really plays a role in the progression. I would say that's the biggest driving factor for mutation testing, planning for future progression for the patient.

Dr. Stump: The other plug is MRD testing. We’re going to be seeing that being done in large centers may have lots of trials open, or maybe a patient's on a clinical trial, and they're using MRD-guided durations of therapy. But unfortunately, we're not at a place where that's going to be routinely applied to most settings.

Dr. Dotson: Great. Another question: What is the threshold for dose modifications that you might have for a BTK inhibitor in terms of adverse events before deciding to change therapy? In practice, the package inserts do reflect a number of dose adjustments that you can do over time. Typically, if you're getting into that second or third dose adjustment and thinking that the patient may not necessarily be tolerating it, that's really the point at which we might switch therapy.

The other thing to think about is, if you're dose-modifying for something that is an acute adverse event or something that really will contribute to more long-term quality, those are really times where I think, is changing therapy in the best interest of the patient?

But, of course, trying dose modification upfront, especially for that first or second adverse event occurrence, can definitely help the patient. There are some data about even dose holidays in certain situations, where stopping therapy and restarting may even be beneficial.

Dr. Campbell: The last question: "How do you manage AEs with non-covalent versus covalent BTK inhibitors?" I think this is an interesting question. Toxicities with covalent and non-covalent BTK inhibitors are used more for driving your treatment decision than how you actually manage the toxicity. I don't necessarily manage hypertension in a patient differently based on which BTK inhibitor they're on, but that may be the basis for why I'm choosing the therapy, why I'm choosing a covalent versus a non-covalent.

They definitely have different toxicity profiles across the spectrum based on the selectivity, as we talked about. But I think that the toxicity profile of each individual drug probably drives your treatment decision more than being unique in terms of how you actually manage it when it manifests itself.

Dr. Dotson: Thank you so much, Pete, Sarah, and to the audience, for participating in this program.