ADVERTISEMENT

Module 1. Overview and Definition of Medication Therapy Management (MTM)

What is Medication Therapy Management (MTM)?

Medication Therapy Management is a specific service that was first described when MTM formally became part of Medicare with the passage of the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA 2003).1 This legislation introduced Medicare Part D, the first outpatient prescription drug benefit for patients receiving Medicare coverage. MMA 2003 contained a mandate that certain Medicare Part D recipients with chronic illnesses should receive counseling (often provided by a pharmacist), in an effort to contain costs and help patients better manage the complex aspects of treating their medical conditions.2,3 The basic goals of MTM laid out by MMA 2003 are outlined in Table 1.

| Table 1. Requirements of MTM Programs Under Medicare Part D3 |

|

Under section 423.153(d), a Medicare Part D sponsor must establish an MTM program that:

- Ensures that covered Part D drugs prescribed to targeted beneficiaries are appropriately used to optimize therapeutic outcomes through improved medication use;

- Reduces the risk of adverse events, including adverse drug interactions, for targeted beneficiaries;

- Enhances cooperation with licensed and practicing pharmacists and physicians,

- May be furnished by pharmacists or other qualified providers;

- May distinguish between services in ambulatory and institutional settings;

- Describes the resources and time required to implement the program, if using outside personnel, and establishes the fees for pharmacists or others.

|

| Adapted from: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). MTM Fact Sheet 2013.3 |

While many professional associations have attempted to define MTM, it is generally accepted that MTM refers to a service between a pharmacist (or other health professional) and an individual (or caregiver) to ensure that the person's overall medication regimen is:4

- appropriate for the patient

- effective for the medical condition(s),

- safe in view of comorbidities and other medications being taken

- being administered correctly, at the correct dose

- able to be taken by the patient as intended

How Does MTM Differ from Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM)?

There may be some confusion about how MTM fits into clinical practice. Other terms such as Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM) have been widely adopted and described by professional associations and government agencies.5 The differences between MTM and CMM also have been debated. In general, MTM may be regarded as more specific to the services applied for Medicare patients, while CMM is an approach used mainly in formalized collaborative practice settings such as accountable care organizations (ACOs). It is important to note that MTM and CMM employ similar skill sets and philosophies, so a pharmacist who learns the principles of MTM might well apply them in the practice of CMM, or vice versa.

What MTM Is, and Is Not

MTM does not require credentialing from payers or institutions and does not always include collaborative practice agreements. In addition, MTM can be performed in a variety of settings including the pharmacy, medical office, or the health plan. MTM does not require but should include a relationship with the patient's primary care provider. While the terms CMM and MTM are sometimes intermixed, they are different services provided to different populations. However, how these services are delivered and the skills necessary to be successful in their delivery are similar. These include:

- Assessment of the patient

- Evaluation of Medication Therapy

- Development and Implementation of a Plan of Care

- Follow-up Evaluation and Medication Monitoring

- Documentation

MTM is not a new idea—nor are these concepts new to pharmacy practice. However, because MTM is included in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, it has become more formalized and more widely accepted. MTM programs are recognized as one way to help address some of the pervasive problems of the healthcare delivery system, including spiraling costs, medication errors, and non-adherence. The pharmacy profession is recognized as one of the most appropriate sources for these services. New trends of partnerships between pharmacy organizations and hospitals, primary care providers, health plans, and employers suggest that MTM is in demand and more pharmacists will need to be trained to deliver these services.

Rationale for MTM services

The Medicare population is diverse, and includes patients over the age of 65 who qualify based on age and financial contributions while others can qualify at a younger age due to disability. As a result, pharmacists performing MTM must understand the underlying issues confronting this population, which include costly medications, multiple chronic diseases, and potential or actual adverse events.

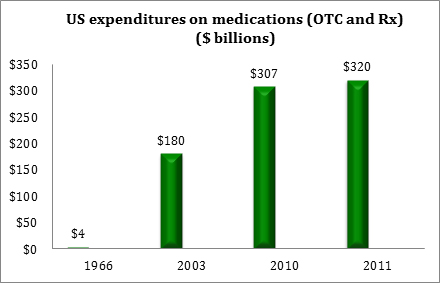

The need for MTM and CMM services has grown steadily in conjunction with the nation's increasing reliance on prescription pharmaceuticals. As shown in Figure 1, Americans' spending on prescription and nonprescription pharmaceuticals has grown exponentially since the 1960s, due in part to the aging of the population, improvements in medical advances, the greater variety of medications available to treat illness, and drug cost increases.6

| Figure 1. U.S. Spending on Medications, 1960s vs. 2000s6 |

|

| Source: IMS Institute for Health Informatics. |

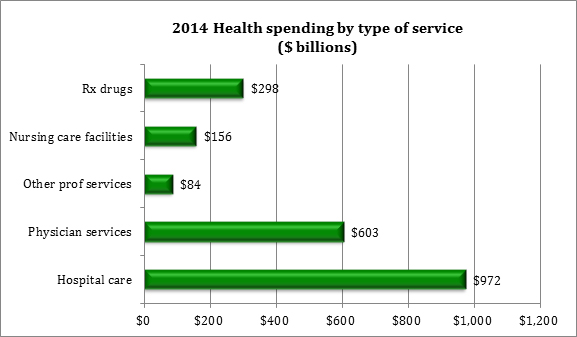

By the end of 2014, total U.S. healthcare expenditures had reached $3 trillion. Between 2013 and 2014, a 5.3% jump in spending was attributed to expanded coverage under the Affordable Care Act. Spending on prescription drugs expanded especially rapidly during that time period, growing 12.2% to a total of $298 billion (See Figure 2).7

|

| Source: Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditures 2014 Highlights.7 |

Chronic diseases account for more than 75% of healthcare costs and are a major driver of pharmaceutical costs. Current data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on chronic diseases indicate:8

- 117 million Americans (about half of all adults) live with at least 1 chronic illness.

- 25% of adults have 2 or more chronic illnesses.

- 86% of all healthcare spending is for people with chronic illnesses.

- Chronic diseases account for 81% of hospital admissions, 91% of prescriptions filled, and 76% of physician visits.9

People with chronic diseases have more doctor visits and more hospitalizations.10 Because these patients often consult multiple providers for different aspects of their condition, healthcare delivery tends to be fragmented, with poor communication between providers. This arises from the orientation of our healthcare delivery system as an acute care model, rather than a chronic care model with emphasis on the whole person.10 There is evidence that poorly coordinated care increases overall costs and hospitalization rates.11,12

People age 65 and older (those eligible for Medicare) are the highest consumers of prescription drugs. Medicare recipients who have multiple chronic illnesses:13

- see an average of 13 different physicians;

- account for 76 percent of all hospital admissions;

- are 100 times more likely to have a preventable hospitalization versus those with no chronic conditions.

With polypharmacy comes a heightened risk of drug-related morbidity and mortality.14-17 The annual costs of morbidity and mortality from medication complications and errors are increasing. As an example, between the years 1995 and 2000, the cost of drug-related complications in ambulatory patients rose from $76.6 billion to $177.4 billion in just 5 years.18

These costs are likely to continue to increase as a greater proportion of the population reaches an advanced age. Pharmacist intervention through MTM can reduce medication-related morbidity and mortality related to polypharmacy. A U.S. Public Health Services-sponsored study showed that employing the services of a consultant pharmacist could reduce the costs of drug-related morbidity and mortality in older patients by $3.6 billion (from $7.6 billion to $4 billion).15

Definitions of MTM

As previously noted, MTM was first described in the MMA 2003,1 which defined MTM as:

- A program of drug therapy management that may be furnished by a pharmacist;

- Designed to ensure that covered part D drugs under the prescription drug plan are appropriately used;

- Designed to optimize therapeutic outcomes through improved medication use and reduced risk of adverse drug events.

In 2004, a coalition of 11 pharmacy organizations arrived at a consensus definition for MTM services as "a distinct service or group of services that optimize therapeutic outcomes for individual patients...independent of, but can occur in conjunction with, the provision of a medication product."19

Why Pharmacists?

Are pharmacists considered to be "providers" by CMS?

MMA 2003 validated pharmacists as valued members of the patient care team. Prescription drug plans were now required to provide health management services (MTM services) to be delivered primarily by pharmacists. MMA 2003 did not go so far as to formally name pharmacists as "providers" —and thus able to receive payments for services directly from Medicare.20 But it did allow pharmacists to bill MTM sponsors (through a third party or directly to insurance organizations) for MTM under three new CPT codes. While Medicare has not recognized pharmacists as providers, approximately 38 states have passed or are considering legislation that recognizes pharmacists as healthcare providers. MTM services provided at the state level (through Medicaid) may pay pharmacists for services if that state has legislation supporting this model. Further discussion of the implications of that legislation and how it may affect pharmacist payments is provided the module on Compensation Models for MTM.

The services that fall under MTM are tailor-made for a pharmacist's skill set, training, and approach to practice. Pharmacists have specialized training in areas that relate directly to MTM services, including:

- Managing multiple medications and combination therapies;

- Use of newer and specialized agents such as biologics;

- Dose preparation and administration of injectable medications and devices;

- Managing and monitoring for adverse effects and safety issues; and

- Addressing patient adherence problems.

Many health authorities have acknowledged the contribution of pharmacists in meeting these needs. A report by the Institute of Medicine stated:21

"Because of the immense variety and complexity of medications now available, it is impossible for nurses and doctors to keep up with all of the information required for safe medication use. The pharmacist has become an essential resource…and thus access to his or her expertise must be possible at all times."

A 2014 report sponsored by 6 large pharmacist professional organizations on pharmacists' roles in the changing healthcare environment (Table 2) stated:22

"Historically, pharmacists' role in healthcare centered around dispensing medications…although they receive training in preventive care, health and wellness, and patient education, pharmacists have traditionally leveraged their clinical knowledge to review prescribed drug regimens to prevent inappropriate dosing and minimize drug interactions. Pharmacists' roles have expanded over time to include more direct patient care…and their roles continue to evolve today."

|

Table 2. Exploring the Role of Pharmacist Services22

- Because accountable care organizations manage the entirety of care, they may look to integrate pharmacist-provided MTM to improve adherence and clinical outcomes while potentially reducing costs.

- Pharmacist-provided medication reconciliation can help reduce medication discrepancies and may be an important component of improving transitions of care moving forward.

- Comprehensive transitions of care programs that utilize pharmacist-provided medication reconciliation will be especially important in the post-hospital discharge setting for patients at risk for hospitalization.

- Payers and policymakers should explore ways to leverage pharmacists' accessibility in the community to provide preventive care services.

- Pharmacists are effective in delivering immunization and screening services

- Pharmacist-provided educational and behavioral counseling can contribute to better outcomes in chronic illness and support wellness in the population.

- Collaborative care models that include a pharmacist can help alleviate some of the demand on physician-provided care.

|

| Adapted from: Exploring Pharmacists' Role in a Changing Healthcare Environment. Avalere Health. May 2014.22 |

Joint initiatives of pharmacy organizations in framing MTM

In 2004 collaboration the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) and the National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation developed the Core Elements of an MTM Service Model, which was revised as Version 2.0 in 2008.19 These important documents provide a framework and basic steps for planning and delivering MTM services. Some of these steps are also reflected in the CMS guidelines for delivering MTM under Medicare Part D.23 Many MTM programs follow the same essential outline, which includes:

- gathering of patient and drug information

- identifying issues and problems

- determining an action plan

- documentation and follow-up

Overall Goals of MTM

The groundwork has now been laid on how MTM evolved, why it is needed, and why pharmacists are ideally suited to provide MTM. The remainder of this introductory module will look at the goals and objectives of MTM, a brief review of the key components of MTM (which are covered in-depth in the following modules), and projecting the future of MTM services.

How is MTM different from other pharmacist services?

Fundamentally, MTM differs from other patient counseling services provided by pharmacists in that it is patient-centered, rather than product-centered, as summarized in Table 3. With most pharmacy services, counseling commences when a patient brings in a prescription or refills a prescription, so the conversation focuses on education pertaining to the particular agent. MTM takes a considerably more comprehensive approach, focusing on the patient's disease state and complete healthcare regimen. It examines what medications the patient is currently taking, as well as what treatments might have been overlooked.

| Table 3. Summary of MTM Goals |

|

Philosophy

- Patient-centered rather than product-centered

- Focuses on overall regimen rather than individual medication

- Collaboration among pharmacists and other healthcare providers

Outcomes

- Increase patients' understanding and self-management skills

Improve patient adherence, thereby enhancing efficacy of medications

Increase adherence to CMS quality performance standards

Mutual goals of MTM for pharmacy organizations, patients, and payers

- Reduce preventable adverse events and associated costs

Reduce medication-related morbidity and mortality

Reduce healthcare costs due to duplicate or unnecessary prescriptions

|

What evidence do we have that MTM works?

Pharmacists embarking on MTM should be aware of the potential impact of these interventions in terms of improving patient care and reducing healthcare costs. Consistent with the goals described above, many evidence-based studies have shown pharmacist interventions to have an impact on health outcomes such as:

- Increased access to services for medically underserved, vulnerable populations

- Improved patient safety

- Alleviated physician burden for health education and counseling

- Adding check/balance system for prescribers to prevent prescribing errors

- Improve patient and provider satisfaction

- Enhance cost-effectiveness

- Improved goal achievement for chronic diseases

Within the past decade, research has been aimed at measuring and quantifying the real-world beneficial effects of pharmacists' care. Table 4 summarizes benefits identified from studies of pharmacist intervention on health outcomes for patients with chronic diseases such as heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

Table 4. Positive Health Outcomes of Pharmacist Interventions:

Evidence from Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| Disease state/condition |

# patients (# studies)

Source |

Outcome/effect of pharmacist intervention |

| Diabetes |

2,247 (16)24 |

Significantly reduced Hb A1c levels |

| Diabetes (10-City Challenge) |

573 (1 multicenter)25 |

Influenza vaccination rate doubled; eye and foot examination rates increased |

| Diabetes (Asheville Project) |

12 community pharmacies followed 5 years26,27 |

Significantly reduced mean Hb A1c; increased % of patients with optimal A1c; improved lipid levels; decreased costs of care; decreased sick days |

| Diabetes (poorly controlled) |

Retrospective review of 100 patient records28 |

Patients with pharmacist-directed MTM had higher rates of medication adherence and lower Hb A1C levels than the non-MTM group. |

| Hypertension |

2,246 (13)29 |

Significantly reduced systolic BP |

| Hypertension, dyslipidemia |

285 (Minnesota MTM Program)30 |

637 drug therapy problems resolved (in 285 patients); HEDIS measures improved for hypertension and cholesterol |

| Hypertension |

Randomized controlled trial of 166 patients receiving MTM or usual care31 |

Pharmacist-directed MTM was more effective than usual care in lowering BP at 6 months in a collaborative pharmacist–physician practice model. |

| Congestive heart failure |

2060 (12)32 |

Reduced all-cause and heart-failure related hospitalizations |

| Patient safety |

298 studies33 |

Significantly fewer adverse drug events; significantly improved adherence, patient knowledge, quality of life |

| Primary care clinics |

38 studies (mostly cardiovascular and diabetes)34 |

Pharmacist interventions in primary care resulted in improvements in blood pressure, glycosylated hemoglobin, cholesterol, CVD risk factors |

| Multiple chronic conditions |

Connecticut Medicaid Project35 |

917 drug therapy problems identified in 369 pharmacist/patient encounters; pharmacists resolved 78% without additional physician visit |

| Hb A1c=hemoglobin A1c; BP=blood pressure; LDL=low-density lipoprotein |

The Asheville Project assessed the impact of advanced practice pharmacists working in coordination with physicians and Diabetes Education Centers.26,27,36 Data collected from this project detailed the impact of pharmacist care on disease management outcomes, quality of life, and economics. According to the authors, the Asheville project demonstrated that pharmacists' services "offer a practical, patient-empowering, and cost-effective solution to escalating healthcare costs."26 In another study by the Connecticut Medicaid system involving 369 patient–pharmacist encounters:35

- 917 drug therapy problem were identified by pharmacists

- 78% were resolved without referring patient back to primary care provider

- 82% of prescribers made changes in therapy based on pharmacists' recommendations

Implementing an MTM Service

How pharmacists implement MTM services will depend mainly on the practice format, the scope of MTM (whether serving mainly Medicare Part D recipients, or reaching a broader target patient group), and the reimbursement structure for these services. MTM services can apply to virtually any patient, in any practice setting.37 The way MTM services are provided is rapidly evolving—at one time, pharmacists could only provide MTM within a contracted organization. Now, pharmacists may provide MTM as staff pharmacists, independent contractors, or as part of an interdisciplinary team (such as a patient-centered medical home).

Issues the pharmacist might consider when planning for a new MTM service are summarized in Table 5.

|

Table 5. Questions to Consider When Planning an MTM Service

- How will MTM services affect workload?

- Time, workflow challenges

- Administrative requirements

- Is there a need to create a space or find a space for face-to-face MTM consults?

- Space for in-person MTM consults

- Are phone or video consults viable?

- What patient populations will be targeted? (Module 2)

- How will patients be recruited?

- How will we address the potential problem of too few referrals?

- How will issues such as language/cultural barriers be addressed?

- What compensation systems will be used in our MTM service? (Module 16)

- What methods will be used to communicate with payers, physicians, and health systems about MTM?

- How will we document effects and impact of MTM in the practice?

- Pharmacist time spent

- Changes in patients' medications, outcomes

- Other impact on pharmacy practice

|

Patient selection for MTM

Patients who are enrolled in Medicare Part D will be invited by the Medicare Part D sponsor to participate in MTM if they have at least 2 conditions from the chronic disease states listed below (some sponsors require 3 or more). Other patients may receive MTM services at the request of their physician, through their employer, at the invitation of the pharmacist, or by self-referral. The next chapter (Module 2) defines the Medicare criteria more thoroughly and contains a comprehensive discussion about how to identify patients for MTM.

Core Chronic Diseases (CMS)

- Hypertension

- Heart failure

- Diabetes

- Dyslipidemia

- Respiratory disease (asthma, COPD)

- Bone diseases (arthritis, osteoporosis)

- Mental health diseases

Overview of MTM Basic Steps

The format for delivering MTM followed in these educational program (explained in detail in the upcoming modules) is drawn from sources including CMS Medicare Part D guidelines, APhA Core Elements, and Patient-Centered Medical Home principles.2,4,19,23 The goal for this educational program is to present a real-world MTM framework that could be adapted for any practice type.

Figure 2 diagrams the basic steps involved in MTM. For Medicare Part D patients, the first MTM encounter involves the Comprehensive Medication Review (CMR) and subsequent quarterly follow-up services involve Targeted Medication Review (TMR), which focuses in on the problems identified in the initial comprehensive MTM interview. More detail on how to conduct each of these steps, in turn, is provided in the following Modules. In the clinical sections of this program, MTM services applicable to that the core disease states are explained using case examples.

| Figure 2. Medication Therapy Management Flowchart |

|

MTM in 2016 and Beyond

With continued changes in healthcare policy we can expect many aspects of MTM—particularly payment and compensation structures—to evolve. This section discusses some areas of change that might affect MTM in the coming years.

Growth and unmet needs in the geriatric population

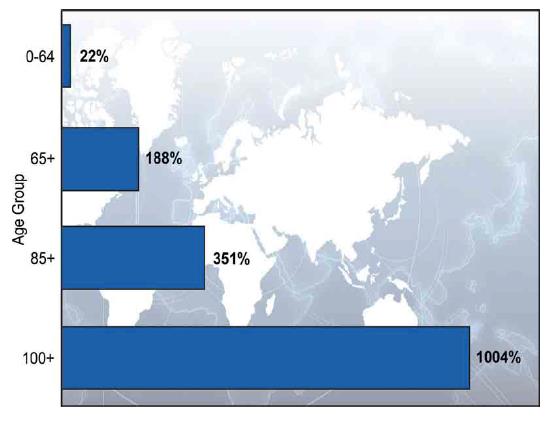

Medication-related problems currently come at a cost of $200 billion. People age 65 and older are the most vulnerable to medication-related problems. By the year 2050, more than 90 million Americans will be in this demographic. In fact, the fastest-growing segment of the population is that of people over the age of 85. According to a study by the World Health Organization, the number of people over age 85 is expected to increase by 351% between the years 2010 and 2050 (Figure 3).38,39 At the same time, health policy experts predict there will be a serious shortage of healthcare providers who are trained to work with the geriatric population.40

| Figure 3. Percentage Change in the World's Population by Age: 2010–2050 |

|

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision.38

- increased volume of newly insured patients (time involved in entering new patient data)

- increased volume and changes in paperwork and documentation

- potentially lower reimbursement per prescription, which may be offset by increased Rx volume

- increased need to communicate with physicians about covered medications

|

Programs in which reimbursement for healthcare services is provided on a capitation basis—rather than a fee for service basis—will greatly increase the need for quality MTM. For example, under Medicare some hospitals do not receive reimbursement if a patient is rehospitalized for certain conditions, which increasing the demand for improved post-discharge management. In the patient-centered medical home model, payers contract with a healthcare organization to cover a certain number of patients ("covered lives") on a per-patient basis, creating an incentive for efficient healthcare cost savings that can be gained through MTM. Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) measures provide standards that must be met in order for physicians to avoid penalties through Medicare. Programs of this nature create more opportunities for pharmacists to get involved in collaborative practice in an effort to improve quality and outcomes in patient care.

Conclusion

This is an ideal time for pharmacists who are not already engaging in MTM to begin the study needed for MTM practice. Currently, there are few employment opportunities for pharmacists related directly to provision of MTM services, but that may be changing. There may be a growing number of new opportunities, such as the inception of Patient-Centered Medical Homes, dedicated patient education programs run by pharmacists in hospitals, and the creation of employer-sponsored MTM and wellness plans. Furthermore, changes in legislature may continue to expand the reimbursement options available to pharmacists. If more states begin to grant provider status to pharmacists, we can anticipate the need for increased credentialing metrics and potentially postgraduate licensure in MTM. Pharmacists who are well versed in the principles of MTM and detailed steps across a variety of clinical areas will be in a good position to meet the needs of a changing health system landscape.

References

- Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA). Cost and Utilization Management; Quality Assurance; Medication Therapy Management Program. Pub L No. 108-173, 117 Stat 2070.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). A Physician's Guide to Medicare Part D Medication Therapy Management (MTM) Programs. MLN Matters Number SE1229.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2013 Medicare Part D Medication Therapy Management (MTM) Programs. Fact Sheet: Summary of 2013 MTM Programs. Sept 12, 2013.

- Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. The Patient-Centered Medical Home: Integrating Comprehensive Medication Management to Optimize Patient Outcomes. Resource Guide, 2nd ed. June 2012. Available at: http://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/media/medmanagement.pdf.

- McBane SE, Dopp AL, Abe A, et al. Collaborative drug therapy management and comprehensive medication management-2015. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(4):e39-50.

- IMS Institute for Health Informatics. The Use of Medicines in the United States: Review of 2011. April 2012.

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditures 2014 Highlights. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/downloads/highlights.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Chronic Disease Overview. Updated Feb 23, 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Report: Chronic Diseases: the Power to Prevent, the Call to Control. At a Glance 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/chronic.htm.

- Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E26.

- Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2269-2276.

- Arend J, Tsang-Quinn J, Levine C, et al. The patient-centered medical home: history, components, and review of the evidence. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012;79(4):433-450.

- Anderson GF. Testimony before the Senate Special Committee on Aging. The Future of Medicare: Recognizing the Need for Chronic Care Coordination. Serial No. 110-7. May 9, 2007, pp 19-20.

- Boparai MK, Korc-Grodzicki B. Prescribing for older adults. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(4):613-626.

- Hanlon JT, Shimp LA, Semla TP. Recent advances in geriatrics: drug-related problems in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(3):360-365.

- Pasina L, Brucato AL, Falcone C, et al. Medication non-adherence among elderly patients newly discharged and receiving polypharmacy. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(4):283-289.

- Tamura BK, Bell CL, Inaba M, et al. Outcomes of polypharmacy in nursing home residents. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):217-236.

- Ernst FR, Grizzle AJ. Drug-related morbidity and mortality: updating the cost-of-illness model. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2001;41(2):192-199.

- American Pharmacists Association and the National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication Therapy Management in Pharmacy Practice: Core Elements of an MTM Service Model. Version 2.0. 2008.

- Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving Patient and Health System Outcomes Through Advanced Pharmacy Practice. A Report to the U.S. Surgeon General. Office of the Chief Pharmacist. U.S. Public Health Service. Dec 2011.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, Ed. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine: Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 2014.

- Exploring Pharmacists' Role in a Changing Healthcare Environment. Avalere Health. May 2014. Available at: http://www.nacds.org/pdfs/comm/2014/pharmacist-role.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CY 2014 Medication Therapy Management Program Guidance and Submission Instructions. April 5, 2013.

- Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, et al. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part I: systematic review and meta-analysis in diabetes management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(10):1569-1582.

- Fera T, Bluml BM, Ellis WM. Diabetes Ten City Challenge: final economic and clinical results. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(3):383-391.

- Cranor CW, Bunting BA, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: long-term clinical and economic outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):173-184.

- Cranor CW, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: factors associated with outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):160-172.

- Skinner JS, Poe B, Hopper R, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of pharmacist-directed medication therapy management in improving diabetes outcomes in patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(4):459-465.

- Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, et al. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part II: Systematic review and meta-analysis in hypertension management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(11):1770-1781.

- Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(2):203-213.

- Hirsch JD, Steers N, Adler DS, et al. Primary care-based, pharmacist-physician collaborative medication-therapy management of hypertension: a randomized, pragmatic trial. Clin Ther. 2014;36(9):1244-1254.

- Koshman SL, Charrois TL, Simpson SH, et al. Pharmacist care of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(7):687-694.

- Chisholm-Burns MA, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, et al. US pharmacists' effect as team members on patient care: systematic review and meta-analyses. Med Care. 2010;48(10):923-933.

- Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA, et al. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(4):608-622.

- Smith M, Giuliano MR, Starkowski MP. In Connecticut: improving patient medication management in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):646-654.

- Cranor CW, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: short-term outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):149-159.

- Stebbins MR, Cutler TW, Parker PL. Assessment of Therapy and Medication Therapy Management. In: Alldredge BK, Corelli RL, Ernst ME, et al. Koda-Kimble and Youngs Applied Therapeutics : The Clinical Use of Drugs. 10th ed. Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- World Health Organization, National Institutes of Health. Global Health and Aging. NIH Publication 11-7737. October 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf.

- United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. Available at: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp.

- Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Buidling the Healthcare Workforce. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catelog/12089.html.

Back to Top