ADVERTISEMENT

Module 4. Developing a Therapeutic Action Plan for MTM

In Module 3, the MTM pharmacist collected patient information from a patient interview and a variety of other sources. This information will be used to determine a course of action, or "Therapeutic Action Plan," and to communicate that plan to the patient and healthcare providers. In addition to documenting the plan, follow-up is a key component to ensure that the desired outcomes are met or modifications can be made to the plan as necessary.

Most MTM formats focus on the development of 2 key documents for the patient:

- Patient-centered medication list or Personal medication list (PML)

- Therapeutic Action Plan (may be called Medication Action Plan or MAP)

The MTM pharmacist might consider combining these documents, if possible, so patients have a medication list that is easy to use with actionable items in one place, as discussed below.

Creating a Personal Medication List (PML)

This document goes by many names, including Patient-Centered Medical Record (PMR), Patient-Centered Medication List (PML), and Personal Medication List (PML). Its goal is to provide a user-friendly reference of all of the patient's current medications, to help them clearly understand why they take the medications and how they are administered.

The PML is different from the types of documents that most pharmacies are currently able to provide for the patient. Due to limitations of existing computer systems, most pharmacists are only able to print out transaction records and standard drug information handouts based on the package insert. The latter are often long, unwieldy documents that do not offer patient-specific information in an understandable format and are likely to be ignored by the patient. In most pharmacy settings, a personalized document that presents this information in a simple, individualized format would need to be generated through the MTM process.

There are a number of sample templates available for generating an electronic PML. However, there is no one template suitable for every pharmacy practice setting. A pharmacy chain or clinic may have its own template, or a pharmacist conducting MTM may create or adapt an existing document. If the pharmacist is working through a third-party service such as Outcomes MTM or Mirixa, specific templates may be provided. However, some templates are proprietary and cannot be widely shared electronically across multiple platforms.

Sharing of health information is a critical part of successful MTM interventions. There is a need for further research and discussion to standardize health information across systems, and it is important for the pharmacy profession to have a say in these issues. Pharmacists need to be familiar with the national health information technology (HIT) infrastructure and standards of Health Information Exchange that other professionals are expected to follow. One example of this infrastructure is the Continuity of Care Document (CCD) using standard Clinical Documentation Architecture. Components of MTM can be shared between providers by means of the Continuity of Care Document. This is the same document that providers utilize to demonstrate "meaningful use" in the CMS electronic health record (EHR) Incentive Program.

Pros and Cons of Existing PML Templates

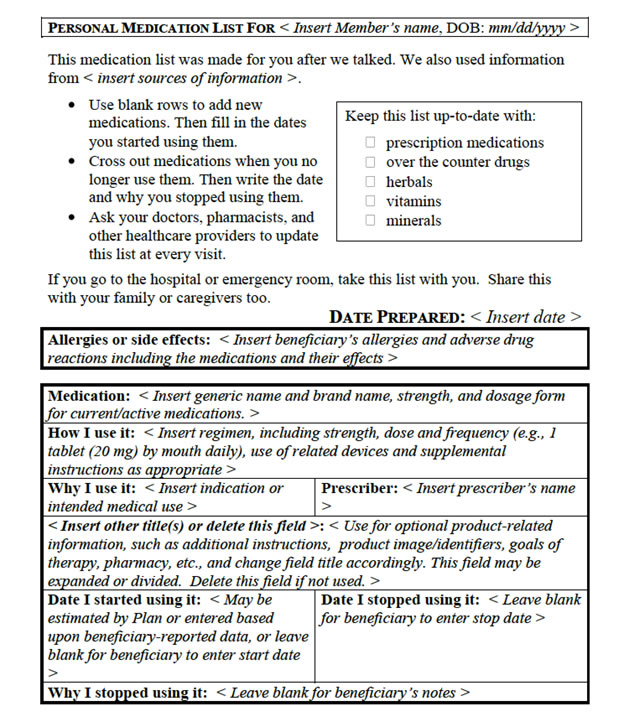

Some of the commonly used PML templates have drawbacks, either by providing too much or too little information. The template provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in its Standardized MTM Format, is shown in Figure 1.1 This basic template provides key information needed in the PML, but lacks flexibility.

Figure 1. CMS Recommended Format for the Personal Medication List

In other examples, the PML may contain too much information. Some of these forms are generated by contracted MTM organizations, or even in discharge summaries patients receive after hospitalization. If the instructions for the patient are buried within an 8-page document loaded with other instructions and fine print, it is likely to be ignored by the patient.

A drawback of many PML formats used today is that they divide the Action Plan and the Personal Medication List into two separate documents. An alternative approach may be to develop one document that provides a brief review of current medications and also indicates any changes or actions that are decided during MTM. This way, patients will have a record of their existing medications and actionable items relating to those medications all in one place. If the MTM provider recommends changes to the medication dosing schedule then sets a follow-up time with the healthcare provider, this information appears with the details of the medication rather than being hidden in a separate document. A suggested template that may be adapted by the pharmacist is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Sample PML With Actionable Items

|

|

Name of Medication |

Reason I Use It (Indication) |

Form

(e.g., pill, patch injection |

Dosage

(How much do I take, how often?) |

Special Notes (e.g., take with food) |

Action Items

Goals, Changes |

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

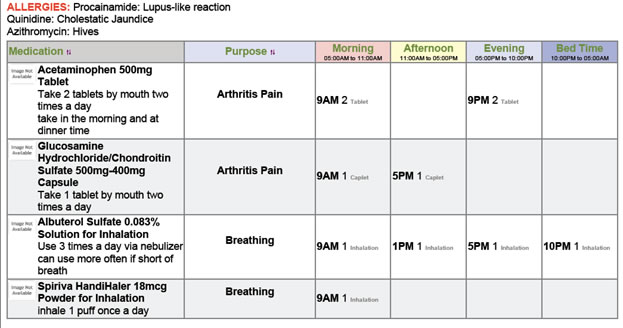

Ideally, forms used for PML should be flexible enough to fit the patient's primary needs. For example, type size may be increased for person with visual impairments. Some patients find it useful to be able to see the drug listing organized by indication (e.g., "On top are the medications I take for my heart condition"). Many people like to have the PML printed to organize the medications by the time of day they're taken. Having a grouping for morning, afternoon, and evening can help the person see at a glance what they'll need to be doing to prepare for and take medications correctly (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. Sample PML Layout By Time of Day

Personal Medication List for Jane Smith

Please share this list with all your healthcare providers

Doctor: John London (Primary care) [Phone]

Doctor: Barbara Wong (Pulmonologist) [Phone]

|

In general, having too many columns or spaces for information can be a source of confusion for patients and extra work for the pharmacist. For example, some PML templates include a separate column for "start date" and "stop date" of a medication. This may be confusing because the information is not applicable to many drugs, such as those taken chronically. Alternatively, if a stop date is necessary (as with antibiotics) this can be added to the dosage instructions. The design of the ideal PML is still a work in progress and will likely continue to adapt as healthcare information-sharing systems change. It is important to keep information and forms as patient-specific as possible.

In summary, a patient-centered PML:

- Organizes the information in a patient-centered manner

- By health condition or indication; or by time of day the medication is taken

- Has the flexibility to be compiled in the manner the patient finds most helpful

- Use symbols, pictures (e.g., image of a tablet, if branded)

- Includes space for action items or reminders, if possible

- Focuses on health literacy

- Provides accurate translation in preferred language, if possible

- Does not bury key drug information among excessive insurance language, technical terms, disclaimers, etc.

- Does not use medical terms a patient would not understand (e.g., calling an agent an antipyretic rather than a fever reducer)

- Does not overuse acronyms (avoid acronyms, abbreviations, or symbols that may be unfamiliar to the patient or create confusion)

Other changes to medication regimen, patient care setting

How Do Patients Use the PML? What is Realistic?

In order to be effective, MTM documents must be realistic with regard to how the patient is willing and able to use them. Ideally, the goal is to develop documents and tools that allow patients to manage their health conditions with less effort.

Are all of the documentation steps requested of the patient realistic? If not, what can be done to simplify this process for the patient? Documentation from CMS recommends that the PML in Medicare Part D direct the patient to:1

- Have your action plan and medication list with you when you talk with your doctors, pharmacists, and other health care providers.

- Ask your doctors, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers to update them at every visit.

- Take your medication list with you if you go to the hospital or emergency room.

- Give a copy of the action plan and medication list to your family or caregivers.

- Use blank rows to add new medications. Then fill in the dates you started using them.

- Cross out medications when you no longer use them. Then write the date and why you stopped using them.

With regard to the Medication Action Plan, the patient is expected to:1

- Read "What we talked about" (on the Action Plan)

- Take the steps in the "What I need to do" boxes

- Fill in "What I did and when I did it"

- Fill in "My follow-up plan and Questions I want to ask"

These might appear to be reasonable expectations but can become unrealistic when considering patients who have multiple chronic conditions. Patients can quickly become confused when keeping up with blood tests, radiologic assessments, physician appointments and/or therapy appointments, and complex daily medication regimens. In many situations, patients will require family or caregiver support to effectively manage their medications.

When developing the PML, the pharmacist conducting MTM should have realistic expectations and be cognizant of individual differences. Starting out with a few basic steps that can be integrated successfully is more effective than giving a patient a long list that will be put in a drawer and forgotten.

Overview of the Therapeutic Action Plan

The Therapeutic Action Plan (also called the Medication Action Plan) is the plan developed through MTM that helps patients to resolve problems related to their medical care and/or to meet specific health goals. Calling this step a Therapeutic Action Plan provides a more comprehensive view of MTM that encompasses nonpharmacologic aspects of healthcare such as screening assessments, lifestyle, and behavioral issues. The Therapeutic Action Plan is a key part of the pharmacist's strategy in MTM.

Each Therapeutic Action Plan will be different for every patient, but there are some general assessment points that the pharmacist should consider during the patient interview. These are summarized in Table 1. This checklist, modified for the patient's specific health conditions, can serve as a basis for identifying medication-related problems, adherence problems, and potential health safety issues or behavioral risks.

| Table 1. Developing the Therapeutic Action Plan: Points to Consider2-4 |

| Question for the Patient: |

Assessment Points for the Pharmacist: |

| What medications are you taking? How do you take this medication? |

- Adherence to the medication regimen

- Potential for unnecessary therapy or duplication of therapy

- Appropriateness of dosage, frequency, route, and time of administration

- Does the patient have any possible contraindications to this medication?

- Is the medication regimen overly complicated (e.g., multiple dosage forms, multiple doses per day)?

- Are specific dosage instructions being followed (e.g., take with food, take on an empty stomach)?

|

| What is this medication used for? |

- How committed is the patient to the need/ rationale for this particular therapy?

- Does patient plan to discontinue the drug when he/she feels better and "doesn't need it?"

- Does the patient understand how the purpose of therapy relates to the way it is used (e.g., PRN "rescue" bronchodilator versus daily maintenance bronchodilator)?

- For high-risk agents: has a risk–benefit assessment been evaluated by the prescriber?

|

| What problems are you having related to this medication? |

- Potential drug–drug, drug–allergy, or drug–condition interactions

- Outward signs of a possible adverse drug reaction, e.g. slurred speech, jaundice, drowsiness, difficulty concentrating

- Is the potential risk of serious complications (e.g., malignancy or infection) worrying the patient in a way that is affecting use of the drug?

- Is the administration method too difficult for the patient (e.g., injected medications, inhalers)?

- If the patient is unsure about adverse effects, the pharmacist may prompt with specific examples related to the therapy.

|

| What is your chief complaint or main health problem at this time? What is the number one thing I can help you with today? |

- Untreated medical conditions that require treatment

- Health problems that a patient may be too embarrassed to bring up with the physician

- Instructions from the physician that the patient does not understand

- Does the physician keep "adding on prescriptions" without regard to the rising copay burden?

|

| Therapeutic alternatives |

- Drug therapies that may prevent an adverse reaction (e.g. antiemetics) or disease complication

- Potentially safer medications

- Dosage forms or devices that increase patient convenience (e.g., autoinjector, patch)

- Known lab values that may help evaluate the appropriateness of drug therapy

- Potential cost savings for patient's medication or treatment regimen

|

| Wellness issues |

- Immunization history

- Recommended preventive care and screening for patient's age and sex (e.g., mammography and PAP test, lipid screening, colonoscopy)

- Smoking and substance abuse cessation

- Exercise habits, weight loss

- Nonpharmacologic approaches (e.g., physical therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, stress management)

|

Summarizing the Therapeutic Action Plan for the Patient

Goals of the Therapeutic Action Plan include:

- Help to create patient activation and engagement to manage his or her own health

- Develop actionable steps for the patient, the pharmacist, and other members of the healthcare team

- Identify and correct medication safety problems or errors

- Explore ways to reduce costs by eliminating waste, improving adherence, and offering less-expensive alternatives when viable

- To ensure patient understanding, pharmacists should use the teach-back method.

- "To be sure we are on the same page, please tell me what we just discussed regarding your medications."

- "What is the most important thing we discussed today?"

The Therapeutic Action Plan will list steps that are recommended for implementation by the patient, a caregiver, or the physician. The physician may need to approve or review some changes before an Action Plan can be distributed to the patient.

The Action Plan should be provided to the patient in writing, either as a separate document or integrated with the PML. Newer formats may allow patients to access and manage this information via their smartphones or other electronic devices. For example, some people with certain chronic disease are using specialized "apps" to keep symptom diaries and log medication dosage or adverse effects. The pharmacist may discuss with the patient how steps from the Therapeutic Action Plan can be integrated into this system. Some MTM services can be set up to print the PML and Therapeutic Action Plan in multiple formats, such as an abbreviated wallet card version plus a standard sized sheet to post on a bulletin board or refrigerator.

To simplify the goals for the patient, many Therapeutic Action Plans present the information to the patient in the following format:

- What we talked about (during MTM)

- What I need to do

- What I did, when I did it

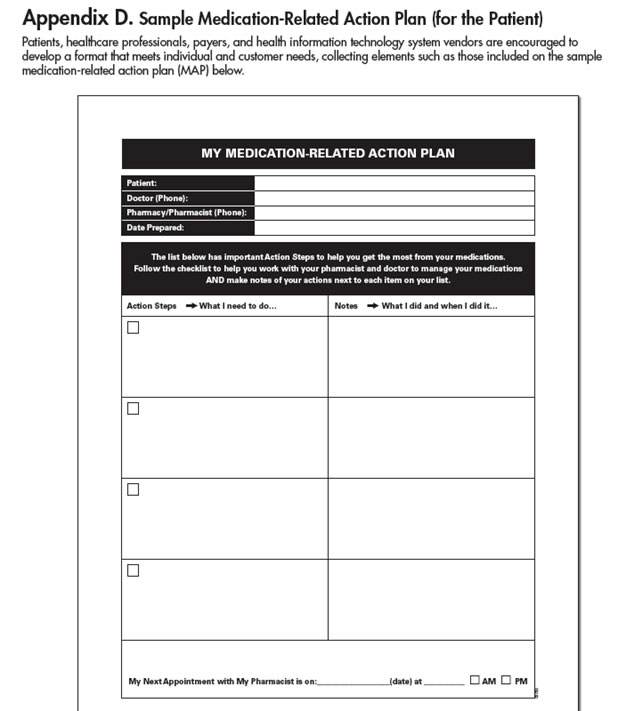

A sample of the CMS action plan (called the Medication Action Plan, or MAP) format is shown in Figure 4.

| Figure 4. CMS Medication-Related Action Plan Template |

|

The Therapeutic Action Plan: What's Realistic?

A potential pitfall of the Therapeutic Action Plan is identifying too many changes and attempting to implement all of them at once. It's important to identify and document all of the issues during an MTM session. The next step is to prioritize them according to their level of importance. The plan is more apt to fail if it is too lengthy or complicated. Instead, start with a goal of 2 or 3 items that can be implemented realistically, and then follow up on their progress before proceeding down the list.

Levels of priority may be determined by the circumstances. Some information uncovered in MTM may warrant an immediate phone call to the physician's office if it involves an aspect of patient safety or medication efficacy. These issues are clearly at the top of the priority list.

Keep in mind that the best therapy for the patient is often the one the patient will take. This issue is covered in more detail in Module 7, Adherence. This concept also applies to what medications the patient can afford. If a patient is nonadherent due to the cost of a medication, then changing the medication to a more affordable drug is a better alternative than missing or stretching out doses.

Following Up to the Therapeutic Plan

MTM should not be a one-time process. Continuity of care is especially needed for the management of chronic diseases that affect much of the population. Giving the person "homework" that helps to engage him or her in a positive way may encourage that person to come back for a follow-up visit. A person who feels that he or she has accomplished a goal will want to share this news with the pharmacist and will want to start on the next steps. However, if the patient is not engaged and does not believe that he or she has gained any benefit from MTM, that person is unlikely to return for a follow-up session.

In order to prepare for successful follow-up, the pharmacist should:

- Set achievable goals for the patient to accomplish before the next follow-up

- Communicate clearly to the patient the plan and time of the follow-up appointment

- Keep clear, updated records

- Communicate/collaborate with physician/healthcare providers when appropriate (see Module 5, Communication Essentials)

Documentation Steps

Documentation is an essential part of MTM. In addition to providing information for the patient, records of the MTM process must be generated for the pharmacy and for other healthcare providers. A common error in medical record keeping is a failure to document the absence of a particular sign or symptom, such as a medication side effect. This has the potential to create confusion or repetition for future healthcare providers, who might think this issue was overlooked rather than simply absent. When a normal result is not documented, screening steps or lab tests may be repeated unnecessarily. There is an old adage, "If it's not documented, it didn't happen." That is, absence of documentation is equivalent to the work not being done at all—which exposes the MTM provider to unnecessary risk of legal liability. In the future, as MTM reimbursement schemes become further developed, documentation will be the basis of payment, regardless of whether the assessment findings were normal.

MTM encounters are usually documented using software provided by the pharmacy. In an optimal world of health information exchange, this documentation would automatically be transferred to the patient's EHR. In many settings this technology is not yet available, so communication with the provider is often done via fax. There are also initiatives to develop secure email systems so MTM documents can be sent directly to providers electronically.

With the move toward provider status for pharmacists, it is advisable that documentation styles be development in alignment with evolving national standards for other healthcare providers. 2012 revisions to the Affordable Care Act allows for payments to providers who participate in Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). Eligibility for the payments depends upon meeting certain quality standards and cost-saving measures. These include:

- patient and caregiver experiences

- care coordination

- patient safety

- preventive health care

- special populations such as frail elderly individuals

Typically the requirements of CMS are also integrated into the requirements of insurance payers as well, especially with regard to MTM and Medicare D since Medicare D, a CMS program is adjudicated through insurance companies.

The required documentation for providers is rapidly evolving with the initiation and rapid implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Thus it is important for MTM providers to be aware of current requirements and changes. Some valuable resources include:

- CMS.gov

- pharmacyhit.org

- Pharmacy Quality Alliance (pqaalliance.org)

- Professional organizations such as APhA, ASCP, and ASHP.

Current knowledge of reimbursement requirements is important for reasons beyond enabling MTM providers to be eligible for payments from CMS. Pharmacist-provided MTM is of value in the context of the outcomes goals of the patient and the overall healthcare team. Thus it is useful for pharmacists to have strong awareness of the factors that drive reimbursements for other members of the healthcare team. For example, physicians must meet "Meaningful Use" documentation requirements related to electronic health record reporting in order to qualify for bonus payments for Medicare and Medicaid services.5 These standards are evolving into requirements and will involve penalties for providers who do not meet meaningful use reporting measures. Meaningful use objectives are summarized in Table 2.5

|

Table 2. CMS Meaningful Use Core Objectives5

- Computerized provider order entry (CPOE)

- E-prescribing (eRx)

- Report ambulatory clinical quality measures to CMS/states

- Implement on clinical decision support rule

- Provide patients with an electronic copy of their health information, upon request

- Provide clinical summaries for patients for each office visit

- Drug-drug and drug-allergy interaction checks

- Record demographics

- Maintain an up-to-date problem list of current and active diagnoses

- Maintain active medication list

- Maintain active medication allergy list

- Record and chart changes in vital signs

- Record smoking status for patients 13 years and older

- Capability to exchange key clinical information among providers of care and patient-authorized entities electronically

- Protect electronic health information

|

Appropriate documentation of MTM by the pharmacist can help the healthcare team meet meaningful use requirements. Attention to appropriate documentation is a high priority in developing a successful MTM program, and the Therapeutic Plan aspect of MTM is where much of the outcomes measures are developed and generated. While these changes are challenging to keep up with, they are also an opportunity for pharmacists as MTM providers to participate successfully as part of the interdisciplinary healthcare team.

Summary and Conclusions

The PML and the Therapeutic Action Plan are standard documents that are part of most MTM systems. Generating printed lists with a lot of information and handing them over to the patient is unlikely to achieve the overall goals of MTM. The information should be presented in a way that is clear, concise, and easily used by the patient. Recommended steps need to be practical and manageable. Sometimes, these may need to be broken down into multiple steps to avoid trying to make too many changes at one time. Follow-up with healthcare providers and documentation of the MTM session is vital to the process of health information exchange among providers. The next section, Module 5, covers Communication Essentials: which includes patient communication and interviewing tips, as well as successful communication with healthcare providers.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D Medication Therapy Management Program Standardized Format. Jan 1, 2013. Form CMS-10396. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/downloads/CMS_10396_MTMP_Standardized_Format.pdf.

- Stebbins MR, Cutler TW, Parker PL. Assessment of Therapy and Medication Therapy Management. In: Alldredge BK, Corelli RL, Ernst ME, et al. Koda-Kimble and Youngs Applied Therapeutics : The Clinical Use of Drugs. 10th ed. Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- American Pharmacists Association and the National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication Therapy Management in Pharmacy Practice: Core Elements of an MTM Service Model. Version 2.0. 2008.

- Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. The Patient-Centered Medical Home: Integrating Comprehensive Medication Management to Optimize Patient Outcomes. Resource Guide, 2nd ed. June 2012. Available at: http://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/media/medmanagement.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare & Medicaid EHR Incentive Program. Meaningful Use Stage 1 Requirements Overview. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/downloads/MU_Stage1_ReqOverview.pdf.

Back to Top