ADVERTISEMENT

The Changing Paradigm of Rheumatoid Disease Management: Challenges and Opportunities for Specialty Pharmacists

Introduction

The rheumatic diseases rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are chronic inflammatory disorders affecting a significant proportion of the US population. Approximately 1.5 million adults (or 0.6%) have RA, and the incidence of RA in women is nearly double that in men.1 PsA is less common than RA, affecting 0.06%-0.25% of the US population.2 However, there is a higher incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis, and studies support that 6%-42% of the nearly 7.4 million adults who have psoriasis are affected by PsA.2-4 AS is estimated to affect 0.2%-0.5% of the population and is twice as common in men than in women.5,6

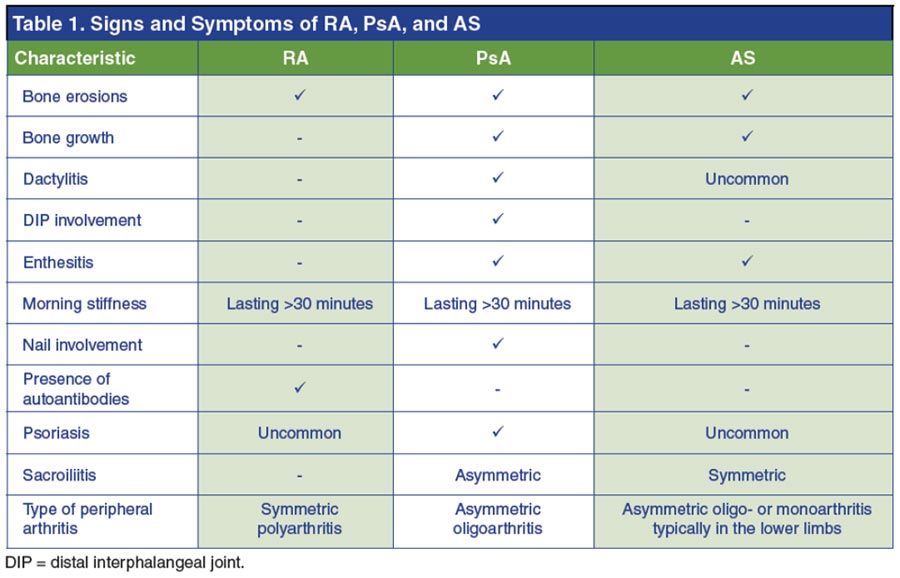

The chronic inflammation associated with these rheumatic diseases may lead to debilitating structural damage or deformity if not treated adequately or early enough.3,5,7-9 Yet, there are important similarities and differences among the signs and symptoms of each disease (Table 1).3,5,10-15 RA is characterized by symmetrical joint inflammation that manifests as stiffness, pain, swelling, and tenderness affecting predominantly the peripheral joints (eg, hands, feet, and wrists).16,17 The majority of patients with RA (50%-70%) are seropositive for the autoantibodies rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA); classically, seropositive RA has been associated with more severe disease than seronegative RA.8 Common extra-articular manifestations include those affecting the skin (rheumatoid nodules), vasculature (vasculitis), eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca), lungs (pleural disease), and heart (pericarditis).17 RA is frequently associated with the development of concomitant comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, infections, and lymphoma and lung cancer, which contribute to an increased risk of mortality.18-20

As with RA, PsA is associated with joint stiffness, pain, swelling, and tenderness.3 Typically, musculoskeletal manifestations of PsA present many years after the onset of dermatologic symptoms.13 Unlike in RA, however, affected joints in PsA tend to be asymmetrically distributed and oligoarticular.11 Furthermore, dactylitis (swelling of the digits), enthesitis (inflammation where ligaments attach to bone), and swelling around the joints of the axial skeleton are common characteristics of PsA but not of RA.10,11 Patients with PsA are at increased risk for comorbidities, including cardiovascular, metabolic, gastrointestinal, ocular, and urogenital diseases.21

AS is a seronegative disease affecting the axial skeleton, which causes inflammatory back pain.5,13 AS usually presents in the third decade of life and includes other symptoms such as sacroiliitis and joint fusion, spinal ankyloses, enthesitis, and peripheral oligo- or monoarthritis.5,9 Potential extra-articular manifestations include anterior uveitis, psoriasis, and colitis.5 In contrast to the progressive cartilage and bone degradation observed in RA and PsA, the structural deformities and immobility associated with AS are typically the result of bony fusions (ankyloses) and growths (syndesmophytes), though erosion does also occur in AS.3,5,8,15

The impact of RA, PsA, and AS on patients' lives is considerable. Patients with RA experience a significant negative effect on activities of daily living, including household and work tasks, as well as overall health-related quality of life.7 Patients with PsA often experience fatigue, disability, and reduced work productivity (or the inability to maintain employment).22 Patients with AS are likewise subject to functional limitations and difficulty in maintaining their ability to work as a result of their debilitating symptoms.9

In recent years, there has been tremendous advancement in the number of therapeutic options for patients with rheumatic diseases. Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have fundamentally altered the treatment paradigms in RA, PsA, and AS, greatly improving outcomes for patients.3,7,9,23,24 Biologic DMARDs, as well as some other recently approved therapies for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, require special handling and ongoing clinical monitoring. The appropriate management of these complex treatment regimens requires substantial patient involvement and education.25 In addition, more and more patients are being referred to specialty clinics for outpatient therapies. As such, pharmacists are ideally situated to serve as a critical source of information for patients and to help facilitate and manage the care of patients receiving complex specialty medications for rheumatic diseases.25

Pathophysiology of RA, PsA, and AS

Although the exact mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of RA, PsA, and AS are not fully understood, years of research have shed light on the predominant genes and signaling pathways involved in the development of these rheumatic disorders. Of note, though various genes have been shown to influence the heritability of each of these rheumatic diseases, a discussion of the genetic mechanisms underlying RA, PsA, and AS is beyond the scope of this review. As many of the currently approved and emerging therapies for the treatment of rheumatic diseases target specific inflammatory molecules or signaling pathways, it is necessary for specialty pharmacists to have a solid foundation of knowledge regarding these pathologic mechanisms.

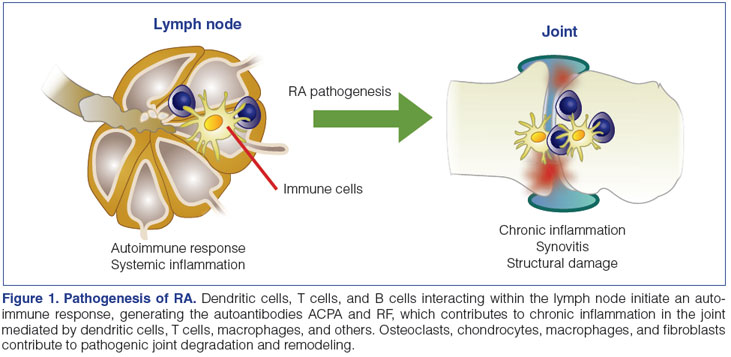

In RA, it is clear that cells of the innate and adaptive immune responses, and their cytokines, are major contributors to the disease process (Figure 1).26 In the lymph nodes, T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells interact to generate a systemic autoimmune response. In the synovium of the joint, T cells secrete proinflammatory cytokines that activate effector cells such as macrophages, fibroblasts, chondrocytes, and osteoclasts to create a destructive inflammatory environment.8,26 Furthermore, many of these effector cells themselves secrete proinflammatory cytokines, which reinforces a positive feedback loop of inflammation.26 Some of the cytokines acting as mediators of the disease process include TNF-α, interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-23, and IL-17.26,27 Cytokines bind to receptors on the surface of cells triggering an intracellular signal transduction cascade that stimulates a proinflammatory response. Though there are numerous intracellular signaling pathways, many of the cytokines thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of RA, such as IL-6 and IL-23, signal through the Janus kinase (JAK) pathway.27 Specific cytokines will activate different cell types, causing chronic inflammation and joint destruction.26 TNF-α-activates white blood cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and osteoclasts to secrete cytokines, matrix enzymes, and other molecules resulting in resorption of cartilage and bone. IL-1 and IL-6 both stimulate white blood cells and osteoclasts. In addition, IL-1 activates endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and chondrocytes, while IL-6 regulates B cell differentiation. IL-23 expands the Th17 cell subset, thereby enhancing IL-17 production, which activates fibroblasts, chondrocytes, and osteoclasts.26

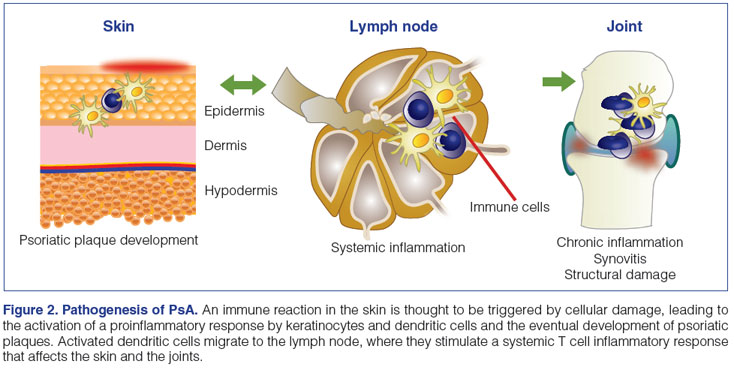

In PsA, the innate immune response is thought to play a major role in the pathogenesis of disease, and similar to the pathophysiology of psoriasis, the Th17 cell lineage seems to be a critical component.10,21 Though many of the same cells and cytokines that are present in the joints of patients with RA are also found in the joints of patients with PsA, histologically, the synovial tissues of patients with PsA are more reminiscent of tissues from patients with spondyloarthritis than RA.10 In PsA synovium, large numbers of T cells (especially clonally expanded CD8+ T cells), B cells, macrophages, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells can be found (Figure 2).13,21 Activated dendritic cells secrete proinflammatory mediators, including IL-12 and IL-23.13 Increased levels of the p40 protein (the subunit shared by both IL-12 and IL-23) are observed in the sera of patients with PsA versus healthy controls.3 Heightened levels of the IL-23 p19 subunit and IL-23 receptor, as well as IL-17 and its receptor, are found in synovial fluid of PsA patients.28 High levels of TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 are found in the synovial fluid of patients with PsA, even at early stages.3

In the skin, psoriasis is thought to arise as a result of an inflammatory reaction to an injury or infection (Figure 2).10 Activated dendritic cells stimulate Th1 and Th17 cells in the lymph nodes, resulting in their migration to the skin, where Th1 cells release interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and TNF-α, and Th17 cells release TNF-α, IL-1, IL-17, and IL-22. Dendritic cells in the skin also secrete IL-12 and IL-23.13 Keratinocytes produce large quantities of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, among other interleukins, chemokines, and antibacterial proteins, triggering the infiltration of neutrophils, resulting in Munro's abscesses (collections of neutrophils), which ultimately leads to the formation of psoriatic plaques.10 Activation of the inflammatory response in T cells, keratinocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells is dependent, in part, upon stimulation of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate and protein kinase A intracellular signaling pathway, which is negatively regulated by phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4).29

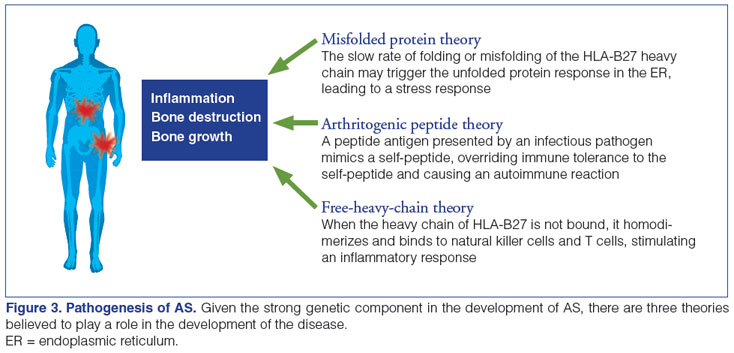

As more than 90% of patients with AS possess the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 gene, it is thought to play a major role in the development of the disease.5,30 Several hypotheses exist regarding how HLA-B27 and other antigens promote AS, including the arthritogenic peptide theory, the misfolded protein theory, and the free-heavy-chain theory (Figure 3).15,30,31

Both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells have been found in the peripheral blood, synovial fluid, and cartilage-bone interface of patients with AS.5 TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 have been implicated, but their exact contribution is not clear. On the one hand, a reduction in the percentage of T cells secreting TNF-α and IFN-γ in the serum of patients with AS has been reported while IL-10 levels were high.31,32 On the other hand, increased expression of TNF-α has been reported in the serum, synovium, and sacroiliac joints of affected patients, and the effectiveness of TNF-α inhibition on disease progression supports a strong role for TNF-α in AS pathogenesis.5,15,33 In recent years, studies have identified that patients with AS demonstrate elevated serum levels of IL-17 and IL-23, increased IL-23 in synovial fluid, and an influx of IL-23 positive cells in the subchondral bone marrow compared to controls.30

Pharmacotherapies for RA, PsA, and AS

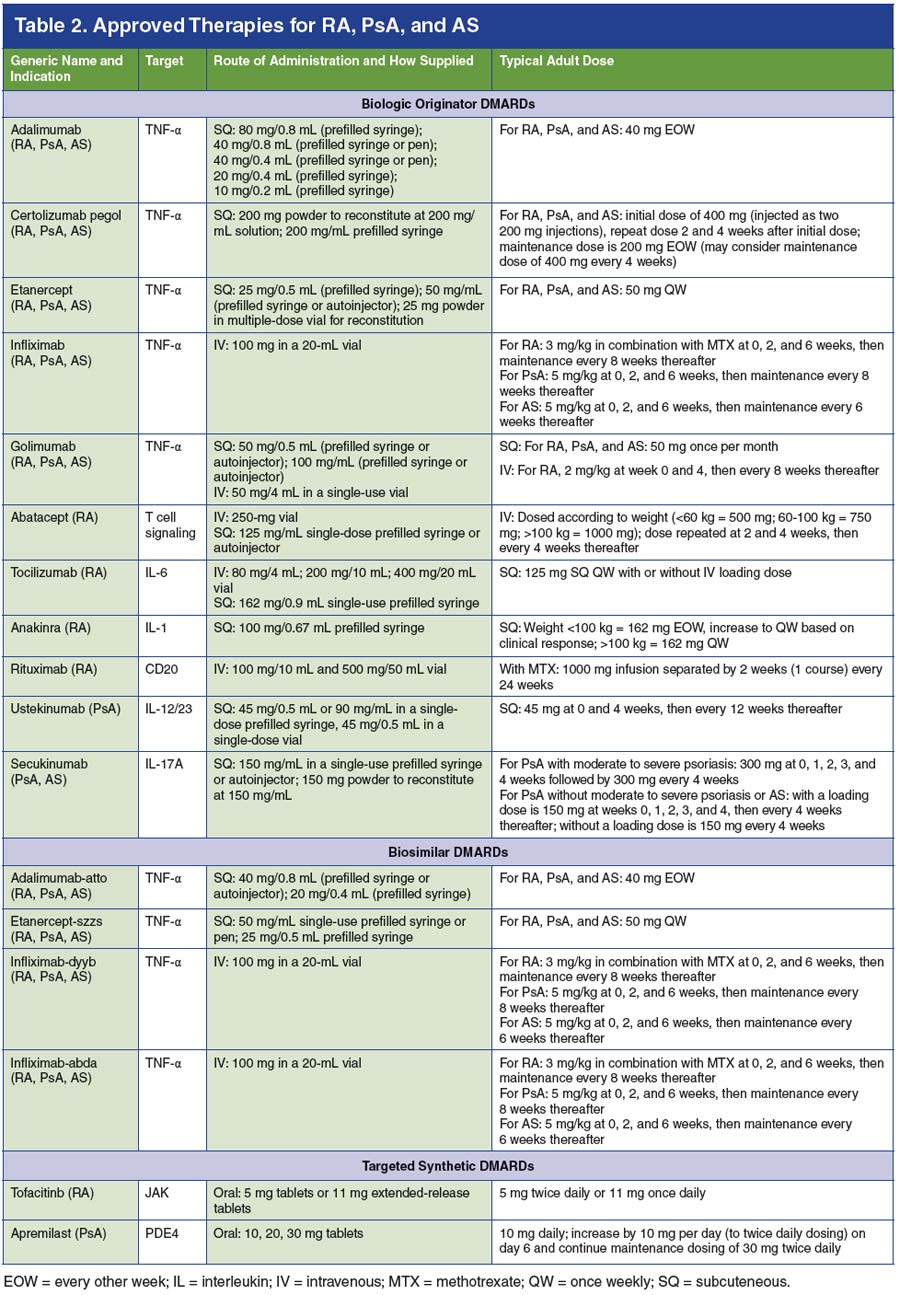

Though RA, PsA, and AS are chronic, life-long illnesses, numerous therapies are available to help alleviate symptoms, lower disease activity, and enhance patient quality of life (Table 2).34-51 Given the complexity and safety considerations associated with these drugs, many require dispensation via specialty pharmacy.25 As such, it is critical for specialty pharmacists to be aware of the many therapies prescribed to patients with rheumatic diseases and to understand how they are used as monotherapies or in combination with other drugs in the management of such patients.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may alleviate pain and improve mild joint symptoms in RA, PsA, and AS.8,9,13 Glucocorticoids may provide rapid relief but are associated with long-term side effects.7,8 Healthcare providers should be aware of the potential for the development of glucocorticoid- induced osteoporosis; importantly, new guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis are expected in 2017 (see: www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support/Clinical-PracticeGuidelines/Glucocorticoid-Induced-Osteoporosis). Conventional synthetic DMARDs, including methotrexate, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, and leflunomide, have been shown to slow disease progression in RA and in PsA, but not in AS.3,7,9,13,24 Often in clinical practice, NSAIDs and steroids are used as bridge therapy upon initiation of a DMARD in order to provide symptomatic relief as the DMARDs begin to take effect. It is important for pharmacists to be aware that patients with rheumatic diseases may be taking NSAIDs and steroids and to ensure that such patients are taking the lowest possible dose for the shortest duration of time so as to prevent the development of serious complications.7,16

Biologic DMARDs have greatly improved outcomes for patients with or without concomitant conventional synthetic DMARD use. Biologic DMARDs used in the treatment of RA include the TNF-α inhibitors adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, and golimumab; the IL-1 antagonist anakinra; the IL-6 antagonist tocilizumab; abatacept, a modulator of T-cell activation; and rituximab, which binds to CD20 and depletes B cells.7,26 Biologic DMARDs used in the treatment of PsA include the TNF-α inhibitors, as well as the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab and the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab.52,53 Of the available biologic DMARDs, the TNF-α inhibitors and secukinumab are approved for the treatment of AS.9,53

Biosimilar DMARDs are follow-on biologic products of already approved biologic originator DMARDs; manufacturers are required to demonstrate highly similar quality, biologic activity, efficacy, and safety to the originator product to gain approval and biosimilar DMARD status.24,54 In the United States, four biosimilar DMARDs have been approved for the treatment of rheumatic diseases: infliximab-dyyb, an infliximab biosimilar (approved in February 2016)54,55; adalimumab-atto, an adalimumab biosimilar (approved in September 2016)54,56; etanercept-szzs, an etanercept biosimilar (approved in August 2016)54,57; and infliximab-abda, an infliximab biosimilar (approved in April 2017).51

In addition, two targeted synthetic DMARDs have been approved for the treatment of different indications.24 Tofacitinib, an oral small-molecule JAK inhibitor, is approved to treat RA.7,58 The oral PDE4 inhibitor apremilast is used to treat PsA.52

Treatment Guidelines

In order to achieve a goal of remission or minimal disease activity in RA, expert consensus recommends a treat-to-target approach that encompasses tight control of signs, symptoms, and inflammation through early and aggressive treatment strategies.23 The ACR guidelines for RA provide comprehensive treatment recommendations based on factors such as duration of disease, level of disease activity, and prior treatment.7 Definitions of disease duration are <6 months for early disease and >6 months for established disease, and disease activity is determined to be low, moderate, or high according to validated instruments such as the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) (online calculator found at: www.4s- dawn.com/DAS28/). The DAS28 measures the number of swollen and tender joints (out of 28), the patient's global health assessment, and the level of C-reactive protein (CRP) or the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to arrive at a score determining the level of disease activity.8 In addition, the ACR guidelines do not include anakinra in their recommendations, as the panel felt this drug was used too infrequently in the treatment of RA and no new data have been published on anakinra since 2012.7

The guidelines advise that DMARD-naïve patients who have early, symptomatic disease receive conventional synthetic DMARD monotherapy regardless of severity of disease.7 In this scenario, methotrexate is the preferred first-line DMARD when not contraindicated. For patients who have early moderate or high disease activity despite conventional synthetic DMARDs, the ACR recommends treatment with a combination of conventional synthetic DMARDs or a biologic DMARD, in no particular order of preference whether a TNF-α inhibitor or non-TNF-α biologic DMARD is used.7 Biologic DMARD therapy should be used in combination with methotrexate whenever possible, because of superior efficacy; in this way, methotrexate may be considered an "anchor therapy," meaning any patient should be considered for methotrexate and any combination therapy should include methotrexate. If a patient fails methotrexate monotherapy, methotrexate should be continued upon initiation of a biologic DMARD unless otherwise contraindicated. If patients have moderate or high disease activity despite treatment with conventional synthetic or biologic DMARDs, the ACR advises that low-dose glucocorticoids should be added for a short duration.7

As with early RA, the ACR recommends that patients with established RA who are DMARD-naïve receive monotherapy with a conventional synthetic DMARD, regardless of disease severity.7 Patients who have established moderate or high disease activity despite monotherapy with a conventional synthetic DMARD should be treated with either combination conventional synthetic DMARDs or the addition of a TNF-α inhibitor, non-TNF-α biologic DMARD, or tofacitinib, in no particular order of preference, rather than continuing DMARD monotherapy alone. As in early RA, methotrexate is the conventional synthetic DMARD of choice for first- and second-line combination treatment scenarios with biologic DMARDs or tofacitinib whenever possible, due to superior efficacy. The guidelines provide further specific direction for patients who fail on multiple drug classes, along with recommendations for RA flares.7

For all patients, a treat-to-target approach requires frequent assessment of disease activity and adjustment of the treatment strategy if the disease is not under control.23 In patients who have established RA and low disease activity, but are not in remission, the ACR advises continuing current therapy rather than discontinuing medication; furthermore, a strong recommendation is made not to discontinue RA therapies in patients with established RA who are in remission. Finally, the ACR guidelines provide detailed recommendations for the treatment of RA patients who have high-risk comorbidities, such as congestive heart failure, hepatitis B or C, previous malignancies, or serious infections.7

Recently, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) issued updated guidelines for the management of RA that highlight treatment principles very similar to those proposed by the ACR.59 Sustained remission or low disease activity should be the goal of treatment for every patient. Methotrexate should be part of the first treatment strategy except in cases where it is contraindicated, at which point leflunomide or sulfasalazine should be used. If the treatment target is not attained with the first conventional synthetic DMARD, the EULAR guidelines recommend switching to another conventional synthetic DMARD in the absence of poor prognostic factors, or a biologic or targeted synthetic DMARD if poor prognostic factors are present. In the latter case, a biologic DMARD is recommended before a targeted synthetic DMARD. Conventional synthetic DMARDs should be combined with biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs whenever not contraindicated.59

In addition, the EULAR guidelines include information on the use of biosimilar DMARDs. Their recommendations state that approved biosimilar DMARDs should be considered to have efficacy and safety similar to their originator products and should be preferred if they are appreciably less expensive than the originator.59 Such guidance on the use of biosimilar DMARDs was not included in the current ACR recommendations due to the lack of evidence available to the panel at the time the guidelines were written.7 However, the US Food and Drug Administration has published a number of guidance documents on the criteria used to determine biosimilar drug status and considerations for the healthcare community (located here: www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm290967.htm).

The goals of treatment for PsA are to help reduce disease activity to the lowest possible level, alleviate pain and inflammation, preserve joint structure, and improve patients' quality of life.3,52 The 2008 American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines for the management of PsA note that patients with mild disease may be effectively treated with NSAIDs and/or intra-articular corticosteroid injections.3 However, methotrexate and/or biologic DMARDs are considered the standard of care for individuals with more significant, moderate to severe disease.

A number of treatment and disease management advances have been made since the AAD published their guidelines in 2008. In order to provide up-to-date information to healthcare practitioners, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), comprised globally of over 500 rheumatologists, dermatologists, and patient research partners, recently issued recommendations on the assessment and treatment of PsA.52 The group notes the importance of evaluating severity of disease within six clinical domains: peripheral arthritis, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, skin, and nails. As with RA, PsA disease severity may be assessed objectively with the use of validated measurement tools.60 For example, DAS28 may be utilized to assess the joint symptoms in PsA, while the assessment of the severity of psoriasis may be accomplished via the Physician Global Assessment, which evaluates the severity of scaling, redness, and plaque elevation on a scale of 0 to 4.61

The GRAPPA recommendations are tailored to address each clinical domain and serve to assist healthcare professionals in their decision to formulate the ideal treatment and management strategy per individual patient.52 For example, in patients with active peripheral arthritis who have not been treated with conventional synthetic DMARDs, GRAPPA recommends treatment with methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, or a TNF-α-inhibitor. In patients who failed initial conventional synthetic DMARD treatment, initiating treatment with a TNF-α-inhibitor, ustekinumab, or apremilast is strongly recommended and the use of secukinumab is conditionally recommended. In any of these patient scenarios, NSAIDs and glucocorticoids may be considered for concomitant use to help improve symptoms. In patients with active psoriasis and PsA—depending on the severity and location of the disease—topical agents, phototherapy, conventional synthetic DMARDs, TNF-α-inhibitors, ustekinumab, secukinumab, or apremilast may all be considered as potential first-line therapies, with or without topical therapy.52

Guidelines for the treatment of AS issued by the ACR, Spondylitis Association of America (SAA), and Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN) specify that the goals of treatment for AS are to reduce symptoms to maintain spinal flexibility and normal posture, reduce functional limitations, maintain work ability, and decrease disease complications.9 As with RA and PsA, validated tools have been developed to help clinicians measure severity of AS disease activity in their patients.62 Included is the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (online calculator found here: www.asas- group.org/clinical-instruments/asdas-calculator/), which takes into account the patient's level of back pain, duration of morning stiffness, the patient's global assessment of health, peripheral joint pain and swelling, and the CRP level or ESR to arrive at a disease activity score.

The ACR/SAA/SPARTAN guidelines note that NSAIDs and exercise have been long considered the mainstays of AS treatment, but the availability of TNF-α inhibitors has greatly altered approaches to therapy.9 Thus, in adults with active AS, treatment with NSAIDs is strongly recommended. If active AS persists despite NSAIDs, the group strongly recommends treatment with a TNF-α inhibitor. No particular TNF-α inhibitor is recommended except in the case of patients with concomitant inflammatory bowel disease or recurrent iritis, who should receive infliximab or adalimumab rather than etanercept.

The guidelines strongly advise against the use of systemic corticosteroids in patients with active disease.9 The IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab was approved for the treatment of AS after the publication of the guidelines.53 Hence, the position of this agent in the treatment paradigm as designated by expert consensus remains to be fully elucidated.

Safety and Monitoring Considerations in Patients Treated For RA, PsA, and AS

The use of conventional synthetic, biologic, and targeted synthetic DMARDs, as well as NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, for the treatment of rheumatic diseases carries with it a responsibility for continuous monitoring of patients for the development of potentially serious side effects. This requires open communication between provider and patient regarding new or potentially problematic medical issues that arise in a patient's life, related or unrelated to the patient's rheumatic disease, which may lead to an increased risk of adverse side effects or drug-drug interactions. It is essential that specialty pharmacists have an understanding of the safety considerations related to these complex treatments and to proactively provide the appropriate initial and ongoing education to patients with rheumatic diseases.25 Vigilance in monitoring for adverse drug reactions is of the utmost importance or else they may go unnoticed.

Screening and Vaccinations

All patients being considered for treatment with biologic DMARDs or tofacitinib must be screened for TB. If patients test positive for TB infection, they must be treated for at least 1 month for latent TB, or as long as necessary for active TB, prior to starting therapy. Patients should also be screened for hepatitis B and C and treated accordingly.7,25,63,64 Formal screening recommendations for patients prior to the initiation of apremilast have not yet been designated by expert consensus; however, it has been suggested that the same screening procedures be used for apremilast as for the TNF-α inhibitors.65

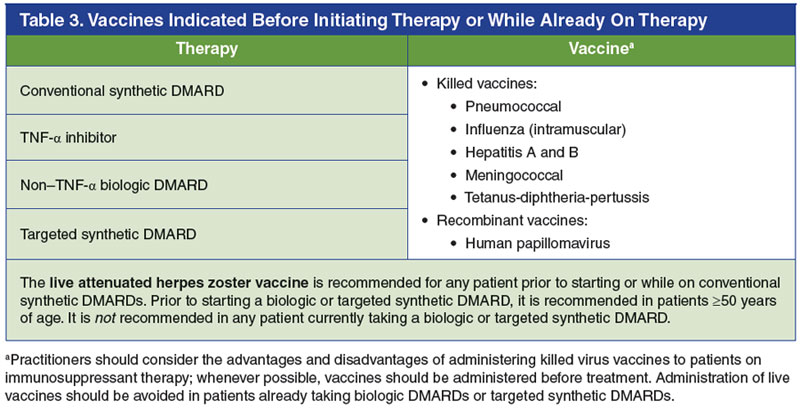

Patients also should be up to date on their age-appropriate vaccinations prior to initiating DMARD treatment (Table 3).7,25,63-66 The ACR guidelines for the treatment of RA recommend the following vaccines be administered prior to initiating any DMARD therapy: pneumococcal, influenza, hepatitis B, human papillomavirus, and herpes zoster (if 50 years of age or older).7 Other standard vaccines such as hepatitis A, meningococcal, and tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis are also reasonable to administer to patients with rheumatic disease prior to initiating therapy if needed.63,65,66 After DMARD therapy has begun, vaccinations are still warranted in patients who require them; however, only killed/inactivated vaccines (not live attenuated vaccines) should be administered in patients receiving biologic or conventional synthetic DMARDs, with few exceptions.63-65 Given these criteria, specialty pharmacists play an essential role in ensuring that patients have had all necessary baseline screening tests performed and vaccinations administered, and that screening tests are negative prior to starting therapies.25

Assessment of Risks for Adverse Events and Monitoring Recommendations

Because the treatments for rheumatic diseases can affect multiple organ systems, monitoring of laboratory parameters such as complete blood count, serum creatinine, liver function tests, and others is advised at baseline and throughout the course of treatment.16,65,66 Specific needs for monitoring vary by agent, and pharmacists should be familiar with these requirements. With methotrexate, there is a potential for patients to develop pancytopenia, hepatotoxicity, pulmonary fibrosis, and negative drug- drug interactions.63,66 Other conventional synthetic DMARDs such as sulfasalazine, leflunomide, and hydroxychloroquine also carry the potential for side effects that require monitoring.16

It is recommended that baseline and ongoing monitoring of blood counts, liver function, and other tests are performed when using TNF-α inhibitors63; patients should be aware of common and sometimes serious adverse events associated with these drugs, including injection or infusion site reactions and increased risk of infection (most commonly nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection).25,63 Rarer but serious side effects of the TNF-α inhibitors include serious infections, malignancies, and reversible drug-induced side effects such as lupus, cytopenia, multiple sclerosis, and development or exacerbation of congestive heart failure.63

Similar baseline and ongoing monitoring is required with the use of non–TNF-α biologic DMARDs and the targeted synthetic DMARDs, which carry their own set of risks.25 With regard to the non–TNF-α biologic DMARDs, some common side effects include:

- Rituximab: severe infusion reactions

- Abatacept: headache, nausea, upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis

- Tocilizumab: headache, hypertension, upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, elevations in cholesterol and liver function tests, decreases in white blood cell or platelet counts; monitoring of lipids, liver function, and blood count is required at baseline

- Ustekinumab: headache, nausea, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection

- Secukinumab: upper respiratory tract infection, cold symptoms, diarrhea

The targeted synthetic DMARDs apremilast and tofacitinib are also associated with reported adverse events. Headache, nausea, dizziness, and diarrhea within the first 2 weeks of treatment with apremilast are common, but typically subside thereafter. Further, weight loss and worsening depression should be assessed throughout the course of treatment.25 Tofacitinib has been associated with increased risk of headache, diarrhea, cytopenias, possible serious infections, and some malignancies, and monitoring of lipids throughout treatment is recommended.25,58,65

As many of the agents approved for the treatment of rheumatic diseases are immunomodulatory, patients using such therapies may be at an increased risk for serious infection. Pharmacists should play an active role in continuous clinical vigilance directed at recognizing and identifying signs and symptoms of infection.25 Not only should pharmacists actively communicate with a patient's healthcare team upon suspicion of development of a serious infection or other adverse event, it is also incumbent upon pharmacists to help patients understand what information they should share with other healthcare providers related to the signs and symptoms of their disease and the development of potential adverse events.

The Pivotal Role of the Specialty Pharmacist in the Management of RA, PsA, and AS

Specialty pharmacists are ideally positioned to provide critical information and care to patients with rheumatic diseases who are taking biologic DMARDs, targeted synthetic DMARDs, or other specialty medications. Education and open communication are essential to help set patient expectations about the course of their disease and potential treatment-associated experiences they may have. For example, specialty pharmacists can educate patients about the length of time it may take for the symptoms of their disease to improve with their current medications.25 Furthermore, they can ask patients directly how they are feeling at each encounter. This includes specific questions about whether patients feel the signs and symptoms of disease (eg, joint swelling, psoriatic lesions, back pain) are improving or whether they are experiencing negative side effects.25

Certain therapies have unique dosing and administration instructions that may lead to discontinuation if patients' expectations are not set appropriately ahead of time.25 For example, the use of apremilast is associated with an increased risk of early side effects, including headache, nausea, and dizziness, that usually subside after 2 weeks of treatment. In addition, for intravenous medications, patients should be made aware of how long the infusion process may take; any NSAIDs or corticosteroids they should take beforehand; and how to optimally manage infusion site reactions, should they occur.25

Specialty pharmacists can also provide critical patient education regarding the proper use of medications. Each of the systemic therapies for rheumatic diseases has its own set of unique instructions for dosage and administration, which pharmacists need to ensure their patients fully comprehend and are aware of.25 For example:

- For some subcutaneously administered drugs, keeping the syringe at room temperature for 30 minutes prior to injection may help minimize pain

- Patients should be educated on the appropriate anatomic sites to inject subcutaneous medications and how to correctly inject the medication, given the delivery system (prefilled syringe, autoinjector, etc)

- Some drugs need to be stored in the refrigerator, while others can remain at room temperature for various lengths of time

- Information on the proper disposal of syringes and autoinjector devices is also crucial

The contraindications and requirements for monitoring for adverse effects with the use of systemic treatments for rheumatic diseases such as methotrexate or biologic DMARDs are numerous; patients need to receive the proper information relevant to their individual needs. For example, patients taking methotrexate need to be counseled on the importance of taking concomitant folic acid supplements, to avoid specific medications (eg, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole), to abstain from alcohol use, and to avoid pregnancy; routine blood work to monitor for pancytopenia will be necessary for the first several months.66 Patients at high risk for pancytopenia should be closely monitored: these include patients who have compromised renal function, elderly patients, those taking multiple medications (thus increasing the likelihood of drug-drug interactions), those with hypoalbuminemia, and patients not on folic acid.66

Specialty pharmacists also serve as resources for healthcare providers and patients to optimize the safe and effective use of immunosuppressant medications. Pharmacists should inform patients who are using DMARDs that they may have an increased risk of infection.25 Preventive measures to avoid infection can be recommended and include advocating for good hand-washing technique, avoiding large crowds and individuals who are ill, and making sure patients' vaccinations are current. When a patient does contract an acute infection requiring antibiotics, it is important to explain to patients that it is typically acceptable to skip or delay injection with their biologic DMARD while they complete their course of antibiotics. In cases where patients taking biologic DMARDs are scheduled to undergo surgery, pharmacists should work with patients' primary care providers to develop a strategy for stopping and restarting biologic DMARD therapy.25

Moreover, as many patients with rheumatic diseases also have concomitant comorbidities, including cardiovascular or respiratory diseases, it is essential for pharmacists to be cognizant of the presence of such conditions and to provide the same level of monitoring and management for these comorbid conditions as is done for the patient's rheumatic disease.20 For example, if patients with RA have undiagnosed or untreated hypertension, this is something pharmacists can easily identify and can address with the appropriate healthcare professional involved in the patient's care.

Conclusions

Recent advances in the treatment of rheumatic diseases have resulted in better clinical outcomes and enhanced the quality of life of patients living with these chronic illnesses. With numerous complex treatment regimens being used regularly in this patient population, it is essential that specialty pharmacists remain knowledgeable about the molecular mechanisms underlying the disease processes, the approved pharmacotherapies targeting these molecular mechanisms, and the important dosing, administration, and safety considerations that go along with the use of these therapies. Pharmacists should take a proactive approach in patient care and in the continuous monitoring for the presence of adverse events and drug reactions. Providing patients with education about their disease and treatments remains a fundamental aspect of patient care, one that specialty pharmacists can regularly engage in. Together, through this interactive and ongoing patient-provider relationship, pharmacists will continue to play an integral role in improving the lives of patients with rheumatic diseases.

References

- Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955-2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1576-1582.

- Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:545-568.

- Gottlieb A, Korman NJ, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis : section 2. Psoriatic arthritis: overview and guidelines of care for treatment with an emphasis on the biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:851-864.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. 2007;369:1379-1390.

- Reveille JD. Epidemiology of spondyloarthritis in North America. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:284-286.

- Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, Jr., et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1-26.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2016;388:2023-2038.

- Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, et al. American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network 2015 Recommendations for the Treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:282-298.

- Barnas JL, Ritchlin CT. Etiology and pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:643- 663.

- Ciocon DH, Kimball AB. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: separate or one and the same? Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:850-860.

- Emery P, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Kalden JR, Schiff MH, Smolen JS. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: evidence based development of a clinical guide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:290-297.

- Mease PJ, Armstrong AW. Managing patients with psoriatic disease: the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Drugs. 2014;74:423-441.

- Rudwaleit M, Metter A, Listing J, Sieper J, Braun J. Inflammatory back pain in ankylosing spondylitis: a reassessment of the clinical history for application as classification and diagnostic criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:569-578.

- Tam LS, Gu J, Yu D. Pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:399-405.

- American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:328-346.

- Cojocaru M, Cojocaru IM, Silosi I, Vrabie CD, Tanasescu R. Extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Maedica (Buchar). 2010;5:286-291.

- Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2287-2293.

- Smitten AL, Simon TA, Hochberg MC, Suissa S. A meta-analysis of the incidence of malignancy in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R45.

- Sparks JA, Chang SC, Liao KP, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and mortality among women during 36 years of prospective follow-up: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:753-762.

- Kerschbaumer A, Fenzl KH, Erlacher L, Aletaha D. An overview of psoriatic arthritis - epidemiology, clinical features, pathophysiology and novel treatment targets. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128:791-795.

- Walsh JA, McFadden ML, Morgan MD, et al. Work productivity loss and fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1670-1674.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

- Smolen JS, van der Heijde D, Machold KP, Aletaha D, Landewe R. Proposal for a new nomenclature of disease- modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:3-5.

- Mullican KA, Francart SJ. The role of specialty pharmacy drugs in the management of inflammatory diseases. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73:821-830.

- McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2205-2219.

- Hodge JA, Kawabata TT, Krishnaswami S, et al. The mechanism of action of tofacitinib - an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:318-328.

- Suzuki E, Mellins ED, Gershwin ME, Nestle FO, Adamopoulos IE. The IL-23/IL-17 axis in psoriatic arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:496-502.

- Schett G, Sloan VS, Stevens RM, Schafer P. Apremilast: a novel PDE4 inhibitor in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2010;2:271-278.

- Jethwa H, Bowness P. The interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 axis in ankylosing spondylitis: new advances and potentials for treatment. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;183:30-36.

- Kim TH, Uhm WS, Inman RD. Pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis and reactive arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:400-405.

- Sieper J, Braun J, Rudwaleit M, Boonen A, Zink A. Ankylosing spondylitis: an overview. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61 Suppl 3:iii8-iii18.

- Gorman JD, Sack KE, Davis JC, Jr. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1349-1356.

- Actemra (prescribing information). South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc; 2016.

- Amjevita (prescribing information). Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc; 2016.

- Cimzia (prescribing information). Smyrna, GA: UCB, Inc; 2017.

- Cosentyx (prescribing information). East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2016.

- Enbrel (prescribing information). Thousand Oaks, CA: Immunex Corporation; 2016.

- Erelzi (prescribing information). Princeton, NJ: Sandoz Inc; 2016.

- Humira (prescribing information). North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2017.

- Inflectra (prescribing information). Lake Forest, IL: Hospira, a Pfizer Company; 2016.

- Kineret (prescribing information). Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB; 2016.

- Orencia (prescribing information). Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2016.

- Otezla (prescribing information). Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2015.

- Remicade (prescribing information). Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2015.

- Rituxan (prescribing information). South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc; 2016.

- Simponi Aria (prescribing information). Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2017.

- Simponi (prescribing information). Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2017.

- Stelara (prescribing information). Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2016.

- Xeljanz (prescribing information). New York, NY: Pfizer Labs; 2016.

- Renflexis (prescribing information). Kenilworth, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, 2017.

- Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1060-1071.

- Koenders MI, van den Berg WB. Secukinumab for rheumatology: development and its potential place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:2069-2080.

- Jacobs I, Petersel D, Isakov L, Lula S, Lea Sewell K. Biosimilars for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases: a systematic review of published evidence. BioDrugs. 2016;30:525-570.

- Blair HA, Deeks ED. Infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13; infliximab-dyyb): a review in autoimmune inflammatory diseases. BioDrugs. 2016;30:469-480.

- Chinn M, Cohen H, Averick A, Ismail Z, Feng X. Cancer biosimilars: regulation challenges and clinical impact. US Pharm. 2016;41:7-12.

- Kaufman MB. Pharmaceutical approval update. P T. 2016;41:748-750.

- Gibofsky A. Current therapeutic agents and treatment paradigms for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:S136-144.

- Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:960- 977.

- Mease PJ. Measures of psoriatic arthritis: Tender and Swollen Joint Assessment, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), Modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (mNAPSI), Mander/Newcastle Enthesitis Index (MEI), Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI), Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC), Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesis Score (MASES), Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI), Patient Global for Psoriatic Arthritis, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Psoriatic Arthritis Quality of Life (PsAQOL), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC), Psoriatic Arthritis Joint Activity Index (PsAJAI), Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA), and Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (CPDAI). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63 Suppl 11:S64-S85.

- Pascoe VL, Enamandram M, Corey KC, et al. Using the Physician Global Assessment in a clinical setting to measure and track patient outcomes. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:375-381.

- Zochling J. Measures of symptoms and disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Scale (ASQoL), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Global Score (BAS-G), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), Dougados Functional Index (DFI), and Health Assessment Questionnaire for the Spondylarthropathies (HAQ-S). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63 Suppl 11:S47-S58.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:625-639.

- Goyal A, Goyal K, Merola JF. Screening and vaccinations in patients requiring systemic immunosuppression: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:179-195.

- Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidence-based guide for primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:787-801.

Back Top