Augmenting Pain Therapy with Self-Massage

Jeannette Wick, RPh, MBA, FASCP

August 30, 2019

INTRODUCTION

Pain and its treatment have riveted the nation for the last 20 years. Americans have heard a virtual pendulum of advice from experts, starting in the 1990s with a concerted effort on the part of accrediting bodies and professional organizations for clinicians to treat noncancer pain more aggressively.1 Following that advice, clinicians did just that. As we entered the 2000s and progressed into the second decade, it became painfully obvious (no pun intended) that the nation faced a crisis – that of opioid abuse. The pendulum swung back to “prescribe cautiously.”

In 2017, the life expectancy in the United States (U.S.) dropped, attributed at least in part to an increase in drug overdose and suicide. This was the culmination of a three-year period of general decline, the first since the 1910s.2 In 2015, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published its Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, effectively recommending that clinicians decrease their reliance on and prescribing of opioid analgesics.3 Opioid prescribing peaked in 2010 at 81 prescriptions per 100 people, dropping to 58 per 100 by 2017. High-dosage (greater than 90 morphine milligram equivalents) prescriptions dropped from 11.8 per 100 in 2008 to 5 per 100 in 2017.4 Clinicians, who have made significant practice changes and decreased opioid prescribing by more than 28%, are still asking an important question4: If not opioids, then what?

Currently, researchers and clinicians are looking for methods and products that can address pain without many of the barriers that patients experience with traditional pharmacologic treatment. These include treatment cost, accessibility, adverse effects, and less-than-perfect response rates. To find good alternatives to opioids, clinicians need to increase their understanding of the different types of pain and non-pharmaceutical options that can supplement and augment analgesics. Researchers at the Mayo Clinic indicate reducing and managing pain using nonpharmacologic interventions is a reasonable and needed approach.5 Self-massage is an option.

Self-massage: History and Utility

Massage therapy has been used around the world to relieve pain for centuries and has been especially helpful for musculoskeletal disorders and stress.6,7 The 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study identified musculoskeletal disorders as 4th in terms of health burden globally, indicating that individuals experienced 21.3% of years lived with disability.8 The areas affected most often were the low back, neck, shoulder, and the knee, with a point prevalence varying between 20% and 50% of the population.8,9 That means that on any given day, 1 in 5 people will report musculoskeletal pain. Physical therapists have used massage therapy successfully, often in combination with exercise therapy, to help people manage their musculoskeletal pain.10 Combination therapy (massage plus exercise and/or medication) has generally shown better effect than any modality alone. Receiving a hands-on massage from a trained massage therapist can reduce pain and stimulate relaxation. A recent Mayo Clinic study undertaken to identify alternatives to prescription analgesics enrolled 1,220 participants. Of those, 87.2% received massage therapy as the intervention. The researchers noted that more than one-third of participants fell asleep during massage therapy; they translated this to mean that these services provided relaxation, a reduction in anxiety, or a reduction in pain.5 Scheduling and paying for such a massage can be inconvenient or difficult. For this reason, many practitioners are introducing patients to manual or device-assisted self-massage.

Many self-massage devices are available in pharmacies. For these reasons, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can benefit by learning more about massage.11 This continuing education activity will review studies that support self-massage use and help pharmacists and pharmacy technicians understand how this therapy works, how pharmacists can counsel patients best, how to determine when self-massage is an alternative or reasonable adjunctive therapy to prescription drugs and opioids, and how to answer patients’ questions.

History of Massage

Massage has been used for centuries, and historians think it was first employed by the Chinese. Historic documents from China mention massage as early as 2700 B.C. Massage was also documented in India as early as 1800 B.C., and they used the words shampooing and rubbing as synonyms for massage. Massage was popular in ancient Greek and Rome, where citizens used it to relax, prepare for tests of strength, to treat medical conditions, and to hasten convalescence. After Rome fell in the 5th century, public nakedness was considered unacceptable in Europe, and mention of massage disappeared until the 17th century. Swedish massage evolved in the 1800s. In the 19th century, practitioners began to combine massage and heat, electricity, and exercise. Increasingly, massage became a leisure and therapeutic tool, and by the 20th century, a body of evidence documenting its mechanisms of action and efficacy started to develop. Today, a number of different massage techniques are commonly employed.12

Overview of Techniques

Therapists and massage therapists use a number of different techniques with their patients/clients. Pharmacists may be familiar with the term Swedish or classic massage, which is currently the most recognized kind of massage. Developed in the late 1700s and early 1800s in Sweden, it relies on 3 techniques: long stroking (effleurage), kneading (petrissage), and friction. Another form of massage, acupressure, originated in China centuries ago and is considered the cornerstone of Chinese medicine. Some forms of acupressure are popular today, with the most popular probably being the shiatsu type massage.13 Shiatsu means something like "finger pressure" in Japanese and involves applying pressure to specific points on the body, moving from 1 point to another in a rhythmic sequence. In general, massage therapists use 8 techniques when working with clients. These are described in Table 1.

| Table 1. Eight Massage Techniques14,15 |

| Technique |

Description |

| Compression |

Increasingly firm pressure on the area, usually using the thumbs to reduce swelling and circulatory congestion, and to numb the nerves slightly |

| Effleurage (stroking or gliding) |

Movement of the hands or massage device up the back and then down the arms (away from the heart) |

| Feathering |

Slow gliding with very light pressure in a zigzag motion over the area |

| Friction |

A slow, pressured glide down the length of the muscle after an area has been warmed up using long flowing motions in the direction of venous flow (toward the heart) |

| Percussion (tapotement) |

Tapping across the muscle structure that starts lightly and progressively becomes harder depending on the recipient’s tolerance |

| Petrissage (kneading) |

Alternatively lifting the skin (squeezing) and grabbing the muscles and fascia (compression) |

| Pressure |

Application of fixed or moving force to the area which can vary from very light to quite deep |

| Stretching |

Slow pushing on opposite ends of a muscle group for 20 to 30 seconds until little resistance is felt |

| Vibration |

Back and forth movement of varying speed and pressure over an area to stimulate the tissues |

Research indicates that various types of massage create a vacuum/suction effect on the circulation that increases turnover of circulatory fluids (blood and lymph) to the area, and transports inflammatory chemicals (substance P, prostaglandins, bradykinin) into the general circulation. This increases concentrations of pain-relieving endorphins and factors needed for metabolic myofascial tissue and the neuromuscular junction recovery.16

Myofascial Release

Another technique that is used by many massage therapists and physical therapists is myofascial release (MFR). MFR employs low-load, long-duration mechanical forces to manipulate the myofascial complex. Intended to restore optimal muscle length, decrease pain, and improve function, MFR is often used in conjunction with conventional treatments. It can provide immediate pain relief and alleviate tissue tenderness. To understand how this technique works, it’s critical to review a little bit of anatomy.17,18

Fascia is a mesh-like connective tissue that is present throughout the body. It has multiple purposes. In the muscular system, it reduces friction between muscles that might work against each other. Some authors indicate that it can be envisioned as a layer of shrinkwrap. There are 2 types of fascia. Superficial fascia is located within the skin at the reticular layer of the dermis. Deep fascia encases blood vessels, bones, muscle, and nerves; it’s critical in tissues that suspend organs and keep them in place.17,18

One of fascia’s most important functions is that of proprioception. Proprioception allows us to self-regulate posture and movement. It depends on stimuli that originate in receptors embedded in the joints, labyrinth, muscles, and tendons. Stress, overuse, traumatic injury, infection, and inactivity can cause fascial restrictions (tightening, tearing, and bunching of the regular fascial structure). Individuals who incur fascial restrictions experience pain and tenderness, and blood flow to the affected area is generally reduced. With prolonged fascial restriction, the tissues may become inflamed and with prolonged inflammation, connective tissue may thicken, causing fibrosis. The astute reader will note a vicious cycle developing. Fibrosis increases pain and irritation, and more pain and irritation causes more fibrosis. Eventually, the individual’s tissue will be scarred and the regular, organized tissue will become a jumble of connective tissue fibers.17,18

MFR is used to stretch the fascia without engaging the muscular stretch response, which, if engaged, would trigger a reaction to pull against the pressure. MFR directs force to fascial fibroblasts, the fascia’s main cell type, and also acts indirectly on nerves, blood vessels, the lymphatic system, and muscles. Fibroblasts appear to adapt to mechanical loading in manners dependent on the strain’s magnitude, duration, and frequency. In the setting of repetitive strain injury, MFR normalizes the apoptotic (cell death) rate, and reduces inflammatory cytokine production.18

MFR seems to lengthen, loosen, and release adhesions in the fascia so that the fascial structure can return to its original position and health.19,20 Therapists who use this technique generally use it in conjunction with a pain management plan. Using direct MFR techniques, the practitioners use knuckles, elbows, or assistive tools to slowly sink into the fascia. They apply a few kilograms of force to restricted fascia and apply tension or stretch the fascia. Indirect MFR—a gentle stretch guided along the path of least resistance until the muscle can move freely—also uses some pressure, with the hands following the fascial restrictions’ direction; the practitioner holds the stretch as the fascia loosens. As with other types of massage and body manipulation, patients often report feeling more relaxed.

Trigger Points

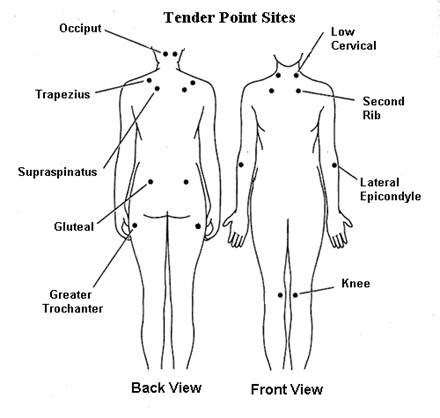

Discussion of trigger points has also increased in the past years, as diagnosis of fibromyalgia has moved from a vague and undocumented condition to an evidence-based diagnosis. Trigger points are locations within the skeletal muscle that are sensitive and painful. Dysfunction in these areas can limit range of function. Touching a trigger point sends a message through the central nervous system and into the brain; patients may feel pain not in the trigger point, but in an area of the body associated with that trigger point. This is called referred pain.14,21 Figure 1 shows trigger points that are important to the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Patients can perform self-massage to release trigger points.

Prescription analgesics are considerably less effective for fibromyalgia-related pain than other types of pain, but massage has proven benefit.22

Self-massage

Massage practitioners use a number of different techniques, and patients can be taught to use these techniques at home. This is referred to as self-massage. When patients use self-massage unassisted by devices, they would employ 2 basic massage moves. In the first, a circular motion massage that can be used for focal aches or pains, patients breathe deeply and slowly. They place a thumb on the middle of the tense or aching muscle and apply enough pressure to feel a “good hurt.” Then, patients slowly move the thumb in a small circle, gradually increasing the circle’s circumference until they are massaging the outer area around the muscle. Patients can repeat this move until they find some relief.23 Pharmacists may need to explain the difference between real pain and “good hurt” to patients. To describe a “good hurt” pharmacists may say that a hurt that is exquisitely tender or a pain that feels good and hurts a little at the same time.21

The second move uses the entire hand and is better suited for large areas of discomfort. In this technique, the patient uses the entire hand but primarily uses the area between the tip of the thumb and the tip of the index finger. Again, patients need to breathe deeply and slowly. They apply pressure at 1 end of the painful area so there is again, a “good hurt.” Once they have applied pressure (and not before), they will rub the entire hand along the muscle’s entire length. When applying this pressure, direction is important. Patients should apply pressure toward the heart and then away from the heart, which simulates a natural blood flow.21,23

A massager is a hand-held object that helps patients massage themselves. Foam rollers and massage sticks are popular, especially for sports-related injuries/recovery/prevention, and generally they are recommended by therapists who show patients how to use them. They also generally have directions included in their packaging. Non-electric massagers come in various shapes and sizes and are used to apply pressure, effleurage, or percussion. Electric handheld devices apply vibration or percussion to the skin’s surface. They are battery operated or activated with a power cord that plugs into an electric outlet.24

Patients who have pain, soreness, or are experiencing stress can perform self-massage on any part of the body that is within their reach; self-massage devices can extend their reach and save their hands from considerable fatigue. Much like an electric toothbrush often cleans teeth better than manual brushing, a handheld self-massage device may be able to deliver massage of a higher quality or amplitude than that delivered by the patient’s own hand.21 Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians need to know some basics about massage when reviewing information about an electric self-massage device25,26:

- Patients may need to use circular motion massage or unidirectional large muscle massage (similar to the self-massage using the hands is described above) depending on their pain type .

- Patients need to understand that massage may cause a “good hurt” and that they need to differentiate between that good hurt (e.g., some pain, resistance, or tension) and massage that increases pain or causes damage.

- Massage works best when patients breathe deeply and slowly.

- Patients should avoid the spine when practicing self-massage and should not use electric massage devices on certain areas (described below).

- Different muscle groups and types of pain require different pressures and “doses” (number and durations of massage sessions) to elicit a response.

Types of Pain

Pharmacy staff often categorize pain using traditional models: acute versus chronic, the World Health Organization pain ladder, or specific diseases or conditions associated with pain. Pain specialists and hospice staff, however, think about pain differently, and examining pain in this way can help pharmacists discuss pain with patients. Hospice specialists are curious about the specific type of pain based on how patients might communicate their different aches, throbs, or twinges. They also use its duration and quality to determine the underlying cause. They listen to the patient’s description and observe nonverbal cues. Adding these clues can identify the root of the problem—be it visceral/soft tissue, bone, neuropathic, pleuritic, colic, or muscular—and suggest appropriate interventions. After all, an aching head suggests an entirely different problem and treatment than severe bone pain. Table 2 describes various types of pain and can help pharmacy staff determine if pain is suitable for massage therapy.

| Table 2. Types of Pain |

| Pain Type |

Presentation |

Examples of Causes |

| Bone pain |

• Ranges from dull to deep and intense

• Usually localized

• Intensifies with movement, weight-bearing exercise, or at night

• Usually in the long bones of the upper arm and upper leg, or major bones (i.e., pelvis, hips, and spine)

|

Cancer metastasis

Adverse effects of drugs

|

| Colic pain |

• Transient cramping, usually in the abdomen or flank

|

Spasms, obstruction, or distention

of a hollow viscera

· Hepatic or biliary colic occurs when a stone passes from the liver or gall bladder through the bile duct. Pain is generally located in the patient’s upper-right quadrant of the abdomen, and often. accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

· Intestinal colic—also called ordinary colic—is caused by gas distending the bowel.

· Renal colic is terribly painful, usually unilateral, and indicates that calculi or stones are passing from the kidney through the ureter.

|

| Fibromyalgia-related pain |

• A burning pain or pins-and-needles sensation, similar to the feeling of blood rushing back into and after it's fallen asleep.

• Generalized aching or a feeling of electric zings

• Painful skin that feels like it's been sunburned.

• Ranges from mild to debilitating and changes frequently and rapidly throughout the day.

|

Unexplained pain after usually harmless things, such as a cold breeze, soft fabric moving across the skin, or light pressure from a handshake. Tight clothing or tags can be irritating.

|

| Muscle pain |

• Soreness, stiffness, or cramping

• May mask bone pain as surrounding muscles contract involuntarily

• Can become chronic and nonspecific

|

Muscle pain often occurs after injury or overuse causes infiltration or occlusion of blood vessels supplying the specific muscle.

May be related to an adverse drug reaction (rhabdomyolysis).

|

| Neuropathic pain |

• Constant superficial burning, varying with the degree of nerve compression or infiltration.

• Patients will describe the pain as burning, needling, stabbing, stinging, aching, shooting, or, sometimes, numbness.

• Risk increases in patients taking neurotoxic agents like metronidazole or isoniazid.

• Occurs more frequently in individuals with diabetes, alcoholism, or severe malnutrition

|

Damage to a specific nerve, plexus, root, or spinal cord.

|

| Pleuritic pain |

• Pain on inspiration

• Patients will say they feel pain

when they inhale and breathe shallowly to guard against severe pain

|

Pneumonia (bacterial, viral, or

parasitic), cough fracture, sickle

cell anemia, pulmonary embolism,

pulmonary lesions, complications

of chemotherapy or radiation,

Guillain-Barré syndrome, and,

rarely, varicella-zoster virus pneumonia

or pericarditis

|

| Visceral pain |

• Pain at viscera or injury site

• The only pain type that is usually continuous; patients usually describe it as aching or squeezing

• Often accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms like indigestion, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, or rectal bleeding

• Pain referred to somatic area supplied by same vasculature

|

Injury, compression, or

tumor in or around an organ, or

abdominal cavity stretching

|

| References: 21 |

Musculoskeletal Disease

Data about massage’s effectiveness in pain management is accumulating, but in certain conditions, good evidence exists to support its use. Researchers from Touch Research Institute at the University of Miami School of Medicine have conducted numerous studies concerning self-massage. These studies have looked at rheumatoid arthritis in upper limbs,27 pain and range of motion in knee arthritis pain,28 hand pain,29 and neck pain.30 These researchers propose several potential mechanisms that decrease pain and sometimes increase range of motion: (1) decreased heart rate leading to a relaxed state, (2) stimulation of pressure receptors that increases vagal activity and serotonin levels (allaying stress and anxiety), and (3) reduction of substance P, a cytokine that increases pain levels, pursuant to massage.27,30 Other researchers suggest that mechanical factors, including changes in fascial adhesions, myofascial trigger points, and viscoelastic properties of tissue, may be at play.26,31

Arthritis. Experts estimate that approximately 12% of adults aged 60 years or older (a rapidly growing population) have osteoarthritis, with most of them experiencing pain in the knee.32,33 The quadriceps may contribute to osteoarthritis-associated knee pain, and muscle massage has been shown to have beneficial effects on pain, stiffness, and physical function.33-38 A meta-analysis of studies of self-massage for a variety of musculoskeletal conditions found low-to-moderate level evidence of benefit in low back pain and shoulder pain.22 A 2017 meta-analysis indicated that in arthritis, massage therapy is “hypoanalgesic.”26

Back pain. Low back pain (LBP) is the most common condition contributing to disability in the U.S.39 Almost everyone experiences back pain at some time, and most improve within a month. Unfortunately, one-third report persistent back pain and for 15% LBP becomes a chronic complaint.40,41 Several randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews support clinical massage therapy delivered by trained professionals in chronic LPB.42-46 LBP treatment guidelines promulgated by the American Pain Society and the American College of Physicians recommend massage for LBP,44,47 although some experts question the recommendation.48 A study conducted in primary care patients recently found that 10 massage treatments were effective for patients suffering with chronic LBP. Further, the researchers found that chronic LBP patients 50 years of age and older seemed to be more likely to respond. Individuals younger than 50 years of age were more likely to drop out of the study. The researchers suggest that these participants may have had more obligations that deterred them from making and keeping appointments.49 Another recent small study found that pain perception was significantly reduced in patients with chronic LBP after a 30-minute massage.50

Fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia has become a growing and more recognized diagnosis in the U.S. People with fibromyalgia often respond poorly to traditional pain relief medications. Several studies have demonstrated that massage therapy improves pain, reduces anxiety, and can have a beneficial effect on depression in patients with fibromyalgia.22,51 A meta-analysis looked at massage use in fibromyalgia and sorted studies by massage style (connective tissue massage, manual lymphatic drainage, myofascial release, shiatsu, Swedish massage, and a combination of different massage styles).52 The researchers reported that myofascial release had beneficial effects on fibromyalgia in terms of pain, fatigue, stiffness, anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Researchers also found that every style of massage, except for Swedish massage, improved symptoms and HRQoL of patients with fibromyalgia.52

Head and neck pain. Headache is another area in which massage has been shown to be beneficial. Approximately 50% of adults experience a headache at least once annually.53 The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke indicates headache is the most common form of pain and a frequently cited reason for days missed at school or work.54 Headache disorders collectively are the 3rd leading cause of years lost because of disability.53 For patients, headaches are agonizing. For healthcare practitioners, headaches are diagnostic challenges and treatment dilemmas. The recently revised Ontario guideline for persistent headache associated with neck pain includes massage as a viable treatment modality.55

Sports-related muscle fatigue and injury. Athletes, coaches, and sports physical therapists often use massage to prevent or treat sports-related injury. Despite its purported benefits and frequent use, few studies have addressed its efficacy.

Dose and Duration

Pharmacist and pharmacy technicians are trained to look at treatment from a “dose and duration” perspective. No guidelines exist that specify the dose or duration of treatment with self-massage (or any type of massage, for that matter). It is clear that in most cases, patients will not see immediate relief. If patients are consistent and patient, regular massage may reduce pain and the likelihood of recurrence. Pharmacists should counsel patients that in the case of injury, recurrence is only less likely if patients stop doing the activity that caused the pain. For example, poor posture and holding the phone using one’s shoulder are common causes of musculoskeletal pain. Patients need to correct their posture and hold the phone differently or the pain will recur.

Most device manufacturers advise using massage 2 to 4 times a day and massaging for short periods of time. Patients who experience pain after massage should reduce the pressure and duration of self-massage the next time they use it.13,14,21

Self-massage devices

Today, technology has made it possible to create devices that simulate many functions previously only performed by humans. Patients who are looking for self-massage devices may ask for recommendations for the best handheld massagers. Pharmacy staff should stress that there is no “best” device. The best tool is that which meets the patient’s needs. Ultimately, patients are trying to accomplish 1 of the following56:

- Increased blood flow: this can be accomplished with heat or with massage techniques including effleurage and pressure

- Decreased tension in tissue: the best approach to decrease tissue tension is to use dry needling (inserting a needle that has no fluid or medication in it into the muscle to relieve tension)

- Promote relaxation: percussion and shiatsu tend to be very relaxing

- Increase range of motion: careful stretching and circular massage can increase range of motion

- Trigger point release: this is best accomplished with compression and friction

Hand-held massagers come in a number of different types. Some are designed for specific areas (e.g., some shiatsu neck and back massagers may drape around the shoulders) while others can be used on the entire body.

Percussion (tapotement) is used to work and strengthen deep tissues and increase blood flow. It’s generally used for large muscles and moderate to severe pain or soreness. Some devices allow patients to adjust the frequency of percussion.

In addition to delivering specific types of massage, some devices also provide heat. Shoulder pain in particular may respond to massage better if the patient applies heat before massaging.21

Selecting Attachments

Products made by various manufacturers come with a variety of attachments, most of which are rubber or plastic. Patients will need to use trial-and-error to determine which attachment works best for their specific concern. Deep muscle attachments tend to be round and will massage the width of the muscle; these can be used on the entire body. Some attachments are prong-like attachments and are designed to feel like human fingers. Attachments that taper to a point are used to massage a specific, concentrated area. Flat discs deliver a gentler massage to a wider area. Devices that include U-shaped attachments are helpful for round areas like the backs of the shins. Attachments that look like stiff brushes are used for acupressure.

Limitations

Few studies have been conducted to determine the efficacy of electric massagers or compare them with massage from a trained massage therapist. One study used focus groups to elicit opinions from consumers and occupational and physical therapists. The study was sponsored by a handheld device manufacturer to determine why product uptake was poor.24 Consumers voiced some dissatisfaction with handheld massage devices. They indicated that they preferred power cords that were long enough to give them freedom of movement and found many devices too large or too heavy. Consumers said that often, the product information was unclear or difficult to understand. The researchers noted that many users ignored the instructions, interacting with the product without reading them. Consumers also perceived some stigma because they associated massagers with adult devices used for intimacy.

The therapists who participated preferred manual hand massage over electronically operated products, citing the therapeutic relationship that develops during 1-on-1 massage sessions. Therapists, like consumers, were concerned about massager size and manageability, and also cited stigmas as a barrier. These finding were reported in 2005 and may not be applicable today.

Counseling points

For the most part, self-massage is a helpful intervention that rarely causes problems when patients understand how to use it and its limitations. Experts indicate that when massage does cause problems, those problems tend to be associated with overenthusiastic or excessive use. This is akin to taking more than a prescribed dose of a medication. Using self-massage devices too robustly can lead to bruising and permanent damage. If patients experience pain, burning, tingling, or numbness, they should stop the massage immediately.21,56

Pharmacists should counsel patients to adhere to their therapy plan. In general, patients will not feel results until they have used self-massage several times. Often when patients’ unrealistic expectations are unmet, they discontinue self-massage too early to see a full effect.21

Massage is contraindicated in certain conditions, and pharmacy staff should be sure to counsel patients that this is the case. Table 3 lists conditions in which self-massage is completely contraindicated or should be used only after careful consideration in collaboration with the patient’s primary care provider.15,21

| Table 3. Contraindications to Self-massage14,21 |

- Active use of supplemental oxygen

- Acute systemic infection (viral or bacterial)

- Aneurysm

- Antithrombotic therapy

- Bone fracture

- Bruising or swelling

- Cirrhosis

- Contact dermatitis or broken skin

- Fever

- Herniated disc, bone spurs

- Intestinal obstruction

- Lymphangitis

- Myocarditis

- Osteoporosis

- Pitting edema

- Pregnancy

- Recent surgery

- Renal failure

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Skin infection

- Tumors

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Uncontrolled seizure

- Venous thromboembolism (pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis)

|

Patients also need to be reminded to avoid massaging some parts of their bodies. All devices have warnings in their product information, but, as noted above, patients often fail to read the directions.24 The first thing to remember is that patients should not massage any artery. When counseling patients, pharmacists should remind patients that they should avoid their carotid artery57; in patient-friendly language, this means telling patients not to massage their necks or the area around the carotid pulse. Pharmacists should show patients where their carotid artery is located by asking patients to place their index and middle fingers on their necks (to the side of the windpipe) to find their carotid pulse. In addition, pharmacists should advise patients not to use self-massage on any area where they feel a pulse point. For example, patients can feel a pulse point in the descending aorta—located deep inside the abdomen. Therefore, patients should move away from the descending aorta.

All massage devices tend to have the same warnings in their product information. Patient should not use massage devices on varicose veins, the front of the neck, the genital area, or on others who are sleeping or unconscious. If the device provides heat in addition to massage, patients should be very careful as heat can cause burns. Some units work with a frozen gel pack. If that is the case, patients should inspect the gel pack and ensure that it is intact before use. Patients should never use a self-massage device under a blanket or a pillow as the unit may overheat. Percussion massagers should never be used on the face, head, or upper neck.

Pharmacists should also be cautious about recommending massage for patients with cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and drugs associated with bruising (see Table 4). Although massage is often used to treat patients with cancer, its use should be restricted to trained therapists who have access to the patient’s complete medical record and history. (Cancer patients may have coagulation problems of bone metastases.) Massage for lymphedema requires professional training.58,59,60 Patients who have cardiovascular disease are often taking anticoagulants or primary or secondary prevention. People who have diabetes may have circulatory problems or neuropathies that numb their appendages. For these reasons, these patients should consult with their care teams before using self-massage devices.

| Table 4. Drugs that Cause Bruising61 |

| Drug |

Indication |

| Anticoagulants and reversal agents |

|

Apixaban

(Eliquis)

|

Direct acting anticoagulant

|

|

Dalteparin

(Fragmin)

|

Anticoagulant

|

|

Prothrombin complex

(Kcentra)

|

Urgent reversal of acquired coagulation factor deficiency induced by vitamin K antagonist (e.g., warfarin) therapy in adult patients

|

| Antineoplastics and cancer drugs |

|

Abiratirone

(Zytiga)

|

Metastatic prostate cancer

|

|

Acalabrutinib

(Calquence)

|

Mantle cell lymphoma

|

|

Avatrombopag

|

Immune thrombocytopenia

|

|

Bevacizumab

(Avastin)

|

Various cancers

|

|

Decitabine

(Dacogen)

|

Myelodysplastic syndrome

|

|

Ibrutinib

(Imbruvica)

|

Mantle cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, chronic graft versus host disease

|

|

Romiplostim

(Nplate)

|

Chronic idiopathic (immune) thrombocytopenic purpura

|

| Corticosteroids |

|

Mometasone

(Elocon)

|

Anti-inflammatory

|

|

Triamcinolone

|

Anti-inflammatory

|

| Epilepsy |

|

Lacosamide

(Vimpat)

|

Partial-onset seizures

|

|

Perampanel

(Fycompa)

|

Partial-onset seizures with or without secondarily generalized seizures in people with epilepsy aged 4 years and older

|

| Neurologic conditions |

|

Amantadine

|

Drug-induced dyskinesia in patients receiving levodopa

Medication-induced movement disorder

|

|

Apomorphine

(Apokyn)

|

Parkinson's disease; acute, intermittent treatment of hypomobility "off" episodes

|

|

Deflazacort

(Emflaza)

|

Duchenne muscular dystrophy in patients 2 years of age and older

|

|

Deutetrabenazine

(Austedo)

|

Chorea associated with Huntington’s disease and the treatment of tardive dyskinesia

|

|

Donepezil

(Aricept)

|

Alzheimer's disease

|

|

Edaravone

(Radicava)

|

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

|

|

Eteplirsen

(Exondys 51)

|

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

|

|

Inotersen

(Tegsedi)

|

Polyneuropathy from hereditary ATTR amyloidosis

|

| Primary and secondary prevention |

|

Aspirin/dipyridamole

(Aggrenox)

|

Prevention of stroke in patients who have had a stroke or transient ischemic attack

|

|

Clopidogrel

(Plavix)

|

Heart attack and stroke prevention in individuals with heart disease

|

|

Prasugrel

(Effient)

|

Used in combination with aspirin for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events (e.g., stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention)

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Amantadine

|

Influenza due to Influenza A virus; Prophylaxis

|

|

Calcifediol

(Rayaldee)

|

Chronic renal failure, Stage 3 or 4 and with serum total 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels less than 30 nanograms/mL

|

|

Deoxycholic acid

(Kybella)

|

An injectable used for reducing fat in the submental region of the face (below the chin)

|

|

Diclofenac

(Voltarin)

|

Analgesic

|

|

Eculizumab

(Solaris)

|

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), and neuromyelitis optica

|

|

Evolocumab

(Repatha)

|

Hyperlipidemia

|

|

Immune globulin

|

Primary humoral immunodeficiency in adults

|

|

Pegloticase

(Krystexxa)

|

Severe, treatment-refractory, chronic gout

|

|

Ruxolitinib

(Jakafi)

|

Intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis

|

|

Sumatriptan

(Imitrex)

|

Migraine and cluster headaches

|

Finally, patients may ask about two additional things. First, they may ask about using lotions and oils with massage. Concurrent use of emollients and massage can improve the massage experience, and some patients may find they help decrease stress and improve the quality of the massage, especially when using effleurage. Adding a scented oil to a massage can introduce an element of aromatherapy, and for patients with dry skin, it can improve the skin’s hydration and elasticity.62-66 Pharmacists should advise patients to read the information included with electronic massage devises before using emollients with them. Some may advise against this practice.

Next, patients may ask if massage is appropriate for children. Many children find massage soothing, and primary care providers may refer children for massage or recommend self-massage. Its suitability depends on a number of factors including the child’s age and maturity. Older adolescents, especially athletes, may be able to use self-massage safely.

Conclusion

Researchers conducted an interesting study germane to massage therapy and published the results in June 2019.67 In this study, the researchers enrolled 366 pharmacists, 212 with acute pain and 154 with chronic pain, to determine what methods that they themselves used for self-management of pain. Interestingly, 28% of the pharmacists with acute pain and 60% of those with chronic pain reported using massage as a self-management mechanism. Pharmacists were more likely to use massage than to step up treatment from prescription analgesics to opioids. It appears, based on this study, that pharmacists are receptive to using massage for pain management. Using the information provided here, they can counsel patients to use massage appropriately. Pharmacy technicians should be aware of these devices and their uses as well.

REFERENCES

- Brennan F. The US Congressional “Decade on Pain Control and Research” 2001–2011: A Review. J Pain Palliative Care Pharmacother. 2015;29(3):212-227.

- Fox M. U.S. life expectancy falls for second straight year-as drug overdoses soar. NBC News. December 21, 2017. Accessed at https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/americas-heroin-epidemic/u-slife-expectancy-falls-second-straight-year-drug-overdoses-n831676, July 14, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html, July 14, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid Overdose. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html, July 14, 2019.

- Clark SD, Bauer BA, Vitek S, Cutshall SM. Effect of integrative medicine services on pain for hospitalized patients at an academic health center. Explore (NY). 2019;15(1):61-64.

- Brummitt J. The role of massage in sports performance and rehabilitation: current evidence and future direction. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2008;3(1):7-21.

- Kong LJ, Zhan HS, Cheng YW, et al. Massage therapy for neck and shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:613279.

- Hoy DG, Smith E, Cross M, et al. The global burden of musculoskeletal conditions for 2010: an overview of methods. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):982-989.

- Picavet HS, Hazes JM. Prevalence of self reported musculoskeletal diseases is high. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(7):644-650.

- Karels CH, Polling W, Sita MA, et al. Treatment of arm, neck, and/or shoulder complaints in physical therapy practice. Spine. 2006; 31(17):E584-E589.

- Chan YC, Wang TJ, Chang CC, et al. Short-term effects of self-massage combined with home exercise on pain, daily activity, and autonomic function in patients with myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(1):217-221.

- Buss IC, Halfens RJC, Abu-Saad HH. The Effectiveness of Massage in Preventing Pressure Sores: A Literature Review. Rehab Nurs. 1997;22(5):229-234,242.

- Weber KK. Complete self massage workbook. London, UK: Collins & Brown; 2015:96 pages.

- Hoyme J. The complete guide to modern massage. Emeryvill, CA: Althea Press; 2018:192 pages.

- Krinsky DL, Ferreri SP, Hemstreet B, et al. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs. Washington DC: American Pharmacist Association; 2018: 41 pages.

- Moraska AF, Hickner RC, Kohrt WM, Brewer A. Changes in blood flow and cellular metabolism at a myofascial trigger point with trigger point release (ischemic compression): a proof-of-principle pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(1):196-200.

- Pax Massage. Fascia, fascial restriction, and myofascial release. Accessed at http://paxmassage.com/assets/docs/Fascia-MJL.pdf, July 25, 2019.

- Meltzer KR, Cao TV, Schad JF, et al. In vitro modeling of repetitive motion injury and myofascial release. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14(2):162-171.

- Ajimsha MS, Al-Mudahka NR, Al-Madzhar JA. Effectiveness of myofascial release: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19(1):102-112.

- Glossary of Ortheopathic Terminology, April 2009. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Accessed at https://www.aacom.org/docs/default-source/insideome/got2011ed.pdf?sfvrsn=2, July 25, 2019.

- Davies C. The trigger point therapy workbook: Your self-treatment guide for pain relief. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2013: 360 pages.

- Bervoets DC, Luijsterburg PA, Alessie JJ, et al. Massage therapy has short-term benefits for people with common musculoskeletal disorders compared to no treatment: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2015;61(3):106-116.

- [No author.] The Self-care Series—Part I, Getting a feel for self-massage. Positive Directions News. 2018;10(1):14.

- McDonagh D, Wilson L, Haslam C, Weightman D. Good vibrations: Do electrical therapeutic massagers work? Ergonomics. 2005;48:680-691.

- [No author.] The self-care series--Part 1, getting a feel for self-massage. Posit Dir News. 1998;10(1):14-17.

- Nelson NL, Churilla JR. Massage therapy for pain and function in patients with arthritis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(9):665-672.

- Field T, Diego M, Delgado J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in upper limbs benefits from moderate pressure massage therapy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19(2):101-103.

- Field T, Diego M, Gonzalez G, Funk CG. Knee arthritis pain is reduced and range of motion is increased following moderate pressure massage therapy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21(4):233-237.

- Field T, Diego M, Delgado J, et al. Hand pain is reduced by massage therapy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):226-229.

- Field T, Diego M, Gonzalez G, Funk CG. Neck arthritis pain is reduced and range of motion is increased by massage therapy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2014;20(4):219-223.

- Monteiro ER, Cavanaugh MT, Frost DM, Novaes JD. Is self-massage an effective joint range-of-motion strategy? A pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2017;21(1):223-226.

- Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(11):2271-2279.

- McAlindon T. The knee. Bailliere Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13(2):329-344.

- Brandt KD. Non-surgical treatment of osteoarthritis: a half century of “advances.” Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(2):117-122.

- Perlman A, Sabina A, Williams AL, et al. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Int Med. 2006;166(22):2533-2538.

- Perlman A, Ali A, Njike Y, et al. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized dose-finding trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):1-8.

- Tosun B, Unal N, Yigit D, et al. Effects of self-knee massage with ginger oil in patients with osteoarthritis: an experimental study. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2017;31(4):379-392.

- Atkins DV, Eichler DA. The effects of self-massage on osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork. 2013;6(1):4-14.

- US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990-2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-608.

- Von Korff M, Saunders K. The course of back pain in primary care. Spine. 1996;21(24):2833-2837.

- Gore M, Sadosky A, Stacey BR, et al. The burden of chronic low back pain: Clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and health care costs in usual care settings. Spine. 2012;37(11):E668-E6677.

- Astin JA, Shapiro SL, Eisenberg DM, Forys KL. Mind-body medicine: State of the science, implications for practice. JABFM. 2003;16(2):131-147.

- Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Kahn J, et al. A comparison of the effects of 2 types of massage and usual care on chronic low back pain: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(1):1-9.

- Chou R, Huffman LH. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):505-514.

- Chou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):492-504.

- Richmond J, Berman B, Docherty J, et al. Integration of behavioral and relaxation approaches into the treatment of chronic pain and insomnia. JAMA. 1996;276(4):313-318.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491.

- Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, et al. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD001929.

- Elder WG, Munk N, Love MM, et al. Real-world massage therapy produces meaningful effectiveness signal for primary care patients with chronic low back pain: results of a repeated measures cohort study. Pain Med. 2017;18(7):1394-1405.

- Daneau C, Cantin V, Descarreaux M. Effect of massage on clinical and physiological variables during muscle fatigue task in participants with chronic low back pain: a crossover study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019;42(1):55-65.

- Li YH, Wang FY, Feng CQ, et al. Massage therapy for fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014 Feb 20;9(2):e89304.

- Yuan SL, Matsutani LA, Marques AP. Effectiveness of different styles of massage therapy in fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Man Ther. 2015;20(2):257-264.

- World Health Organization. Headache disorders fact sheet. Accessed at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/, March 12, 2019.

- National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (NINDS). Headache: hope through research. 2012. Accessed at http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/headache/detail_headache.htm, March 12, 2019.

- Côté P, Yu H, Shearer HM, et al. Non-pharmacological management of persistent headaches associated with neck pain: A clinical practice guideline from the Ontario protocol for traffic injury management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Eur J Pain. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1374. [Epub ahead of print]

- Myofascial Pain Solutions. What is the best handheld deep tissue massager? Accessed at https://myofascialpainsolutions.net/massage-therapy/best-deep-tissue-massager/, July 27, 2019.

- Grant AC, Wang N. Carotid dissection associated with a handheld electric massager. South Med J. 2004;97(12):1262-1263.

- Izgu N, Metin ZG, Karadas C, et al. Prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy with classical massage in breast cancer patients receiving paclitaxel: An assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;40:36-43.

- Gras M, Vallard A, Brosse C, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicines among cancer patients: a single-center study. Oncology. 2019;97(1):18-25.

- Maindet C, Burnod A, Minello C, et al. Strategies of complementary and integrative therapies in cancer-related pain-attaining exhaustive cancer pain management. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(8):3119-3132.

- IBM Micromedex. Drugs that cause bruising. (2019) In Micromedex (Columbia Basin College Library ed.) [Electronic version]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics. Accessed at http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/, July 27, 2019.

- Tosun B, Unal N, Yigit D, Can N, Aslan O, Tunay S. Effects of self-knee massage with ginger oil in patients with osteoarthritis: an experimental study. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2017;31(4):379-392.

- Nasiri A, Mahmodi MA. Aromatherapy massage with lavender essential oil and the prevention of disability in ADL in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;30:116-121.

- Khorsand A, Salari R, Noras MR, et al. The effect of massage and topical violet oil on the severity of pruritus and dry skin in hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2019;45:248-253.

- Pehlivan S, Karadakovan A. Effects of aromatherapy massage on pain, functional state, and quality of life in an elderly individual with knee osteoarthritis. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2019 May 30. doi: 0.1111/jjns.12254. [Epub ahead of print]

- Cheraghbeigi N, Modarresi M, Rezaei M, Khatony A. Comparing the effects of massage and aromatherapy massage with lavender oil on sleep quality of cardiac patients: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;35:253-258.

- Slack MK, Chavez R, Trinh D, et al. An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter? Scand J Pain. 2018;18(4):645-656.

Back Top