ADVERTISEMENT

Herpes Zoster Vaccination: What Clinicians Need to Know to Improve Vaccination Rates

» Slides PDF Handout

PAUL G. AUWAERTER, MD, MBA, FIDSA: Hello and welcome to this Clinical Dialogue, Herpes Zoster Vaccination: What Clinicians Need to Know to Improve Vaccination Rates. I'm Dr. Paul Auwaerter, Sherrilyn and Ken Fisher Professor of Medicine and Clinical Director at the Division of Infectious Diseases here at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and also Chief Medical Officer for the Johns Hopkins Point of Care Information Technology, or also known as the Johns Hopkins POC-IT Center, here in Baltimore, Maryland.

Joining me today are two expert clinicians. Physician assistant Deanna Bridge Najera works at the Department of Emergency Medicine at Carroll Hospital in Westminster, Maryland. Deanna also works as a PA at the TrueNorth Wellness Center in Hanover, Pennsylvania, and also at the Agricultural Worker Program in Gettysburg.

Also joining us is Dr. Michael Hogue. Dr. Hogue is Dean and Professor of the Loma Linda University School of Pharmacy in Loma Linda, California.

I want to thank you both for joining us in this important continuing medical education. So let's go ahead and get started.

So, I think for many of my patients, they're often a little confused about chickenpox, zoster. They said, "I had chickenpox, or I never had it." Tell us a little bit about how we should describe zoster to our patients.

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA, MPAS, MS, PA-C, NCC, DFAAPA, CAQ-Psych: When we're speaking with our patients about herpes zoster, it is very difficult to differentiate exactly what we're talking about. And most often, we start by saying, "Did you have chickenpox?" And then they say, "Well, what does that have to do with anything?" And the important thing is saying that the chickenpox virus “wakes back up”, and that's what results in a zoster outbreak.

And when we say the word herpes, people are often very concerned that we might mean herpes simplex, which is different. This is herpes zoster, herpes referring just to the blistering aspect.

Zoster is a painful rash that occurs along a dermatome, along a nerve pattern. This can be along the side of the face, the torso or anywhere in the body. But it occurs with a prodrome of burning, tingling, irritation, and then a painful, red, blistering rash will appear.

MICHAEL D. HOGUE, PharmD, FAPhA, FNAP: So, shingles is not only painful in the acute phase, because definitely once a person has the shingles, they never forget it. But there's a risk of developing something called postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). And PHN can last for weeks to months and can be quite debilitating, interfering with an individual's ability to function and perform their activities of daily living.

The pain is incredibly difficult to treat pharmaceutically. We really don't have great drugs. The antivirals have very little effect on appropriate treatment or intervention with PHN. And the pain medications that we have really do not work very effectively in treating PHN. So postherpetic neuralgia is such a significant factor with these patients.

But beyond PHN, we can have even further complications with a condition, obviously, if we were to develop ocular shingles. We can lose eyesight beyond just being very painful if the optic nerve is involved. So there are some pretty serious complications associated with shingles. It's not just a small, friendly rash.

PAUL AUWAERTER: I think most patients have probably known someone that's had shingles, and they understand that. I think it gets confusing when you use terms like varicella-zoster virus or herpes zoster, and often that creates more difficulties.

But I think the points you make are very important, that prevention is really the best key, because we really want to try to avoid the need for narcotics if someone has a severe, painful condition, or many of the medications that might be used to manage postherpetic neuralgia.

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: And in addition to the postherpetic neuralgia, other complications can include pancreatic and liver involvement. But then also, the skin conditions that can associate with scarring, and even keloid formation. So it's not just the momentary having the rash, it's the postherpetic neuralgia and some other complications.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Especially for patients who, as they get older, might have comorbidities, immunosuppression and so on and so forth. It's always best to get something on board that might help prevent before they get to that illness where there's increased rates of both shingles and postherpetic neuralgia.

MICHAEL HOGUE: I think it's also important to note that we have about a 1 in 3 chance of developing the shingles in our lifetime. And if you reach age 85, that goes up to a 50/50 chance of developing the shingles. So this is not something that can be ignored, because many people are at increased risk, and especially people who are over age 65.

PAUL AUWAERTER: So, I do both primary care and infectious diseases. And a lot of times, shingles comes up in really the worst times. I recently had a patient whose wife just passed. He was 80, developed terrible zoster ophthalmicus over his face. So it involved his eyes, his face. So painful, he was just really distraught. That's someone in their 80s.

But really, who's at risk, Deanna? Who should we be thinking about in terms of any kind of prevention strategies?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: Certainly. Well, early is always better than late, but there is an increased risk as you approach 60, 65, and then certainly by the 80s. But really, 65 is that kind of golden age where we really want to get them to be vaccinated because of that marked increase in incidence at that time.

MICHAEL HOGUE: I think there's also a pretty substantial increased risk you'll find in patients who are immunocompromised or who have underlying immunocompromising conditions. We know that this is including patients who have HIV, who have a significant increased risk of developing shingles.

But leukemia patients, lymphoma patients would be other examples. Solid organ transplant patients, all of these patients are likely to experience shingles at a higher rate than patients who don't have those underlying conditions.

I would also mention that there's some evidence to show that patients with chronic underlying conditions that are not considered necessarily immunosuppressive may also have increased risk of shingles, such as diabetes. And so there's a wide range of patients who are at increased risk beyond just the age factor, which is important.

PAUL AUWAERTER: And Michael, I think you make great points on the immunosuppression aspects. As an infectious disease clinician in the hospital, I actually see some of the worst cases, where people have multiple dermatomes or the virus has spread, and it has caused a hepatitis. It can cause stroke, multi-organ system involvement, even pneumonia. And so these are all things that I think are very important.

And one of the other aspects, since there's not as much zoster virus circulating in the community because of successful immunization of children against chickenpox, adults are not getting that natural booster as much.

So I think as we have an aging population, we're going to see more and more of this kind of problem for patients, because, without immunization, you know, they really will have an immune system that has a weaker control of the virus.

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: To your point with the case example that you gave of any kind of physical or psychological stress. And so you have individuals that have multiple kind of hits against them as far as mood, loss of a partner or any other health issues, they were recently hospitalized for pneumonia. They're starting to feel better, and suddenly they're hit a second time with that zoster outbreak.

PAUL AUWAERTER: These viruses, of course, have this latency, and the escape from control really can be both physical and emotional stressors, for sure.

MICHAEL HOGUE: And so while many people will only have a single case of shingles in their lifetime, because our population is aging, we're living longer, and because of the factors that we've talked about earlier relative to lack of natural infection, because of effective pediatric vaccination against chickenpox, we are seeing more and more patients, it seems, that have a second case or a third case because of these factors.

So it's important to know that once you've had shingles doesn't mean that you're not at risk any longer. You could be, in fact, based on life circumstances, still at increased risk.

PAUL AUWAERTER: So, in terms of prevention, in 2006, the first vaccine was licensed, which was a live attenuated zoster vaccine for people that were age 60 or older at that time. How well are we actually doing with use of that original zoster vaccine, Michael?

MICHAEL HOGUE: Well, data tells us that we had a Healthy People 2020 goal to achieve at least 30% vaccination, and we did accomplish that and exceeded just a little bit. But still, yet, over 60% plus of patients remain unprotected against zoster even with the previous vaccine in place. So we have significant room to improve there.

Not only that, but we've seen that we have significant disparities that exist across the country. For example, individuals who live in the South were much less likely to be immunized against zoster than individuals, let's say, that live in the West. New York and New Jersey had lower immunization rates, just as an example, than other parts of the Northeast. So there definitely are differences from state to state and from region to region in the country.

And not only that, we see that there are differences in ethnic groups that receive the vaccine. Caucasian patients receive vaccine more frequently than underrepresented minority groups. The immunization rates across the board are still not where they need to be, and there's lots of room for improvement.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Deanna, you know, vaccines are all sometimes quite a tough proposition to get people to get them. What's your sort of view here?

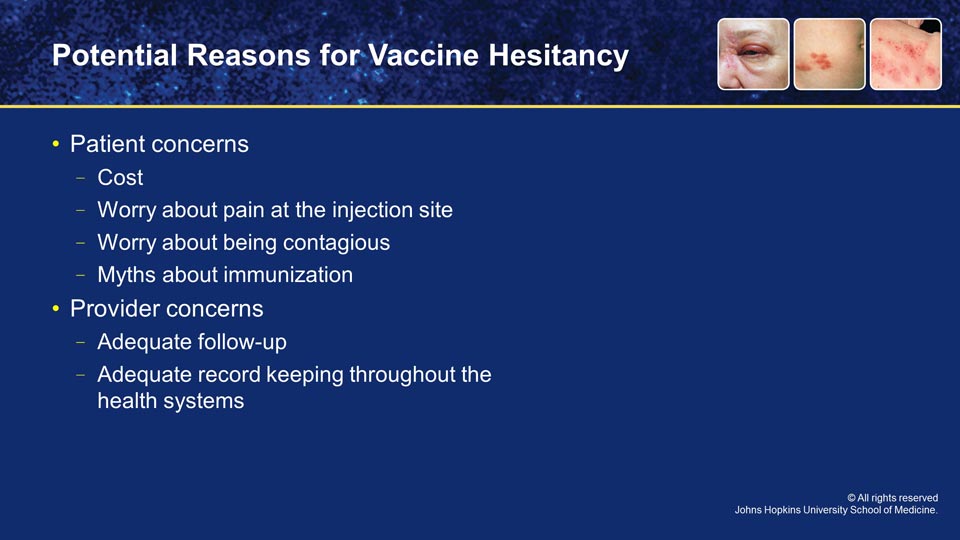

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: The vaccine hesitancy can come from various factors. And so really figuring out for that specific patient in front of you what are their concerns is the best place to start. Is it cost? Is it worried about pain at the injection site? Is it worried about, will I be contagious? Or is it just simply they don't know about it, and they're not sure what will happen if they get the immunization. So having that conversation often is a good launch point.

But then also, there's the follow-up. You know, with the immunizations, how are we keeping a record of that? If we're giving it not in a primary care provider's office, how are we getting that information back to the primary care provider, if it's given in a pharmacy or in an emergency department or wherever they may have gotten it, how is that connecting to their patient medical record?

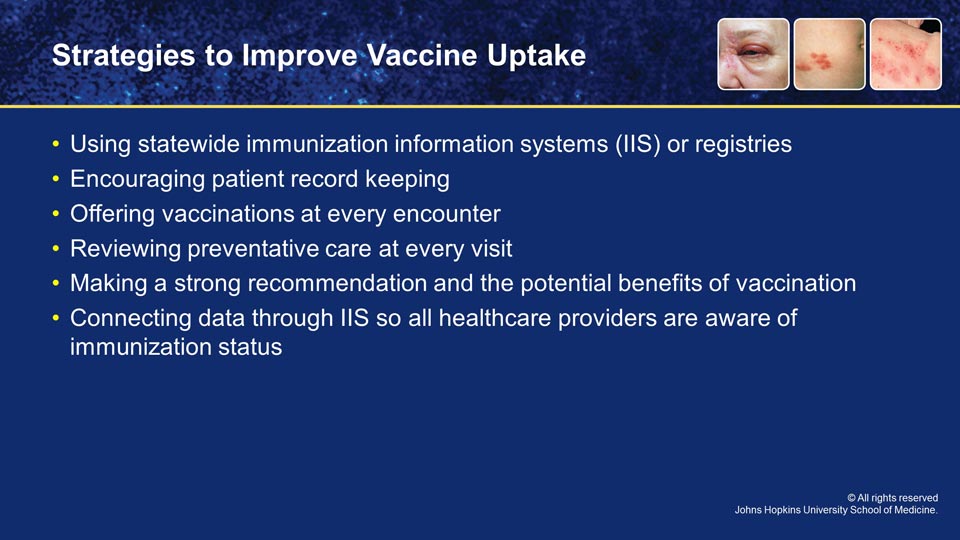

There are statewide immunization information systems (IIS), but unfortunately, not a federal one yet, which is also another challenge. And with the patient medical record, often there is electronic access, but again, the communication between health systems is often not ideal.

Encouraging the patient to reply back, giving them even a little handheld wallet card that writing down immunizations, when they received one, when they should get the next one, all of that can go a long way. But just because a patient says no today doesn't mean they should say no tomorrow.

So, really encouraging them every visit of reviewing what preventative care they've had, what they're eligible for, what they should be getting, and including vaccinations in that conversation.

PAUL AUWAERTER: I've usually found that if you can make a strong recommendation or a rationale why they would benefit from it and say, "This is something I really think is important," that carries a fair amount of weight.

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: And once they see a friend experience shingles, often they're much more likely to come in for the vaccination, too.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Absolutely.

MICHAEL HOGUE: Personal experience with vaccinations is certainly a major factor in determining whether or not one's going to be immunized with any other vaccine in the future. So you have to understand where patients are coming from and advocating with them in a very personal way for them to be vaccinated at the present time.

One takeaway I hope everybody has from this program as we're talking about zoster immunization is to make sure that your practice is connected to your state's immunization information system, and connecting data so that all healthcare providers caring for the patient will be aware of the immunization status of the patient.

PAUL AUWAERTER: People are used to influenza, they're used to tetanus. But then there's something new.

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: You're coming in for your annual influenza vaccination. Why aren't we bringing up to date your pneumonia vaccine or, in this case, the shingles vaccine?

MICHAEL HOGUE: In fact, the National Vaccine Advisory Committee and the CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices strongly recommends that all healthcare providers at every healthcare visit review the comprehensive vaccine needs of patients so that we can make sure that everyone's up to date on every vaccine at each visit.

PAUL AUWAERTER: That's an excellent point, Michael.

PAUL AUWAERTER: As I had mentioned, in 2006, we had our first live attenuated zoster vaccine, the ZOSTAVAX [Merck] . But more recently, there has been an approval by the Food and Drug Administration of a second vaccine for the prevention of shingles, and this was a recombinant subunit -- so not a live virus vaccine -- that goes by the trade name of SHINGRIX [GlaxoSmithKline].

As clinicians looking at both of these vaccines, what's the efficacy of each? What's the differences, Michael, if you would start?

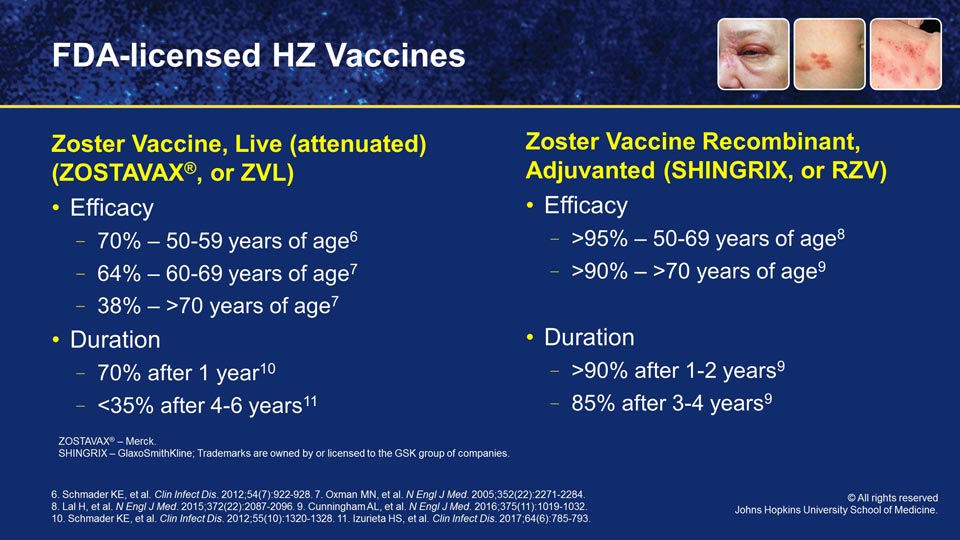

MICHAEL HOGUE: Well, let me start by just letting everyone know that the CDC often refers to these two vaccines by abbreviation, and so I want to talk about that real quickly. The adjuvanted zoster vaccine that you referred to is often just referred to as RZV. The attenuated live herpes zoster vaccine that you referred to is often referred to as ZVL. So if you see those in print, you'll understand that's what these mean.

Both vaccines were studied in very large populations, the recombinant vaccine in over 30,000 people, and the live vaccine attenuated was covered in about 50,000 participants. So rather large trials in both cases.

The biggest differences that we've seen were in efficacy with the two vaccines. For example, in the live vaccine, there was about a 70% efficacy for the younger population, 50 to 59 years of age, and about 64% efficacy when you reached age 60 to 69. So a little bit less efficacy as we grew older. And then that declined pretty sharply for patients who were over age 70 with the live attenuated vaccine to down to about 38%.

With the recombinant vaccine, on the other hand, what we saw in that trial was a 95%-plus efficacy in people who were 50 to 69 years of age. And then what was remarkable was persistent efficacy, a greater efficacy than 90% in patients who were over 70 years of age. That's a remarkable difference between the two vaccines in terms of efficacy.

What's even more remarkable is the duration of that efficacy, because we knew through clinical experience and data over a number of years after the vaccine was brought to market that the live attenuated vaccine had about a 70% efficacy after 1 year, but after about 4 to 5 years, that efficacy declined to less than 35%.

What we're seeing with the recombinant zoster vaccine, however, is that about 90% efficacy after 1 year, and then that persists to not less than 85% 4 to 6 years later. So this persistence of efficacy is a remarkable difference between the two vaccines.

PAUL AUWAERTER: How might you relate to patients the power of the newer recombinant vaccine?

MICHAEL HOGUE: Well, it's important for patients to know that there's the shingles, and then there are the long-term pain effects that can happen with the shingles.

So I would want patients to understand that if they get the shingles vaccine that there is a 12-fold decreased risk of developing the shingles, and there's an 11-fold decreased risk of having a long-term pain.

PAUL AUWAERTER: So for a DNA virus, this is really a rather remarkable reduction. Deanna, what else are takeaways from the studies?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: With the recombinant there is an increased reaction at the site of the injection. And this can be swelling, redness, but also particularly pain. And so patients might interpret this as having an allergic reaction to an injection.

They might call the pharmacist or the provider or come to the emergency department saying, "I had an allergic reaction. I don't think I should get the second vaccine. And then also, what do I do about this right now?"

And it is important to reassure the patient that this is pretty common, and to treat it as you would any kind of bump or bruise, with over-the-counter medications for discomfort, ice to the affected area, and also moving the arm or limb that it was given into to help reduce that discomfort.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Yeah, I think the novel immune adjuvant in the recombinant vaccine is sort of part of the secret sauce for success, and I often tell patients, "Well, thank goodness you had a good reaction, because it means you actually are getting a great immune response there as part of it. So your body has a strong reaction."

So these were two vaccines in very large studies. Were there serious adverse events? I mean, do they happen with any frequency?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: Again, always a very good question, and looking at the data, the reaction of anaphylaxis, of having a really systemic reaction, was the same or less than any other immunization that's out there. So, safety-wise, this is the same as getting a flu or a pneumonia vaccine or any of the other vaccines that we recommend.

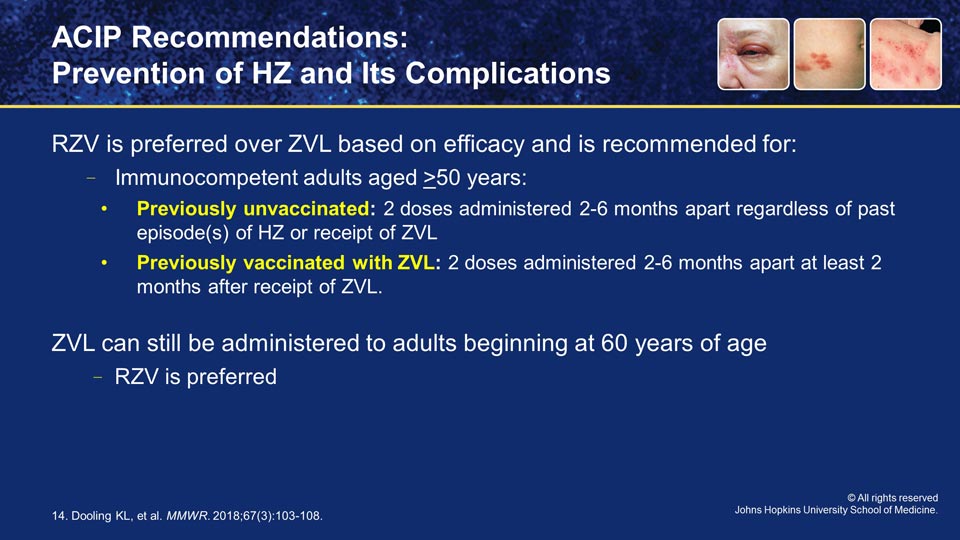

PAUL AUWAERTER: So, Deanna, looking at all the efficacy and safety data, how did the ACIP shape their most recent recommendations for the prevention of shingles?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: Initially, with the live vaccine, that recommendation was slightly different than what's going on now with the recombinant subunit vaccination.

With the recombinant vaccination, they are recommending 50 and older, and two doses of the vaccine. Between 2 and 6 months apart is preferable, but if a patient comes in 8 months after their first vaccine, they can go ahead and get that second one at any time.

Furthermore, if they had gotten the live vaccine at some point, because the recombinant subunit is so much more efficacious, both with the prevention of shingles and the prevention of postherpetic neuralgia, they are recommending that you go ahead and re-immunize with the recombinant subunit vaccination.

PAUL AUWAERTER: And I think the panel also made it a preferred vaccine on the basis of the efficacy, some of the things Michael talked about, although there's still the possibility that a clinician could choose either.

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: Absolutely. And there may be reasons, personal preference, cost, other things to take into consideration. They are both still on the market and available.

PAUL AUWAERTER: And there are fewer contraindications using the subunit vaccine as opposed to the live virus?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: Right, being that it's recombinant versus live, the immunocompetence component is not a contraindication.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Michael, with the two vaccines, what are some of the key differences between them that people that are giving the vaccine should know about?

MICHAEL HOGUE: Well, first of all, the one thing that's similar is they're both approved by the FDA for use in individuals 50 years of age and older. That's about where the similarities end and the differences begin.

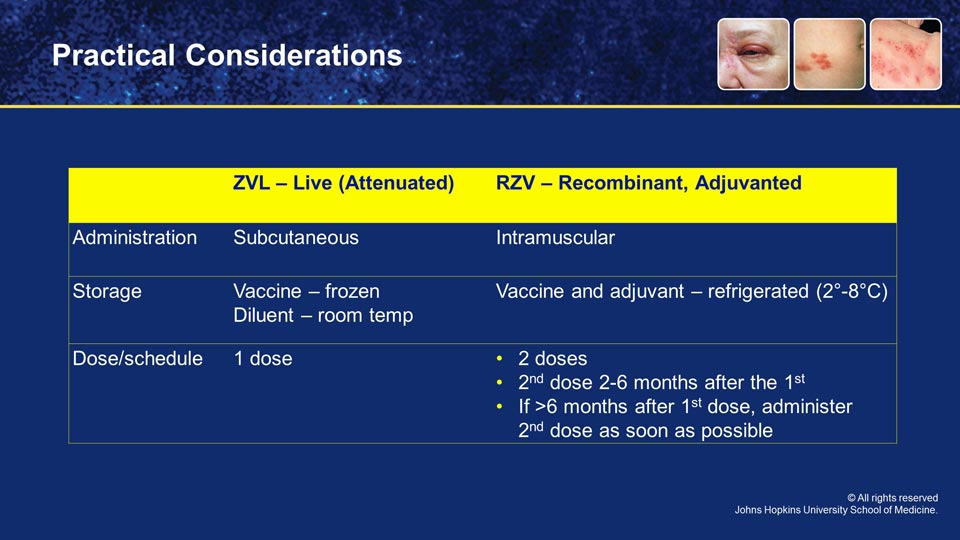

The live attenuated vaccine is administered subcutaneously, in the back of the arm typically, whereas the recombinant subunit vaccine needs to be administered intramuscularly.

Now, if for some reason you forget and accidentally administer the vaccine subcutaneously, the manufacturer and the CDC tell us that you do not need to re-administer that dose of the vaccine. However, we really do want to try to administer it correctly the first time. That's very important.

The second big difference that we want to talk about is storage and handling of the vaccines. As many will know, the live attenuated vaccine came with two vials, one vial that contained the vaccine, and it had to be frozen. The other vial was a diluent, and that diluent has to be stored at room temperature. So, very important that it's not stored in the freezer.

That's a big difference from the recombinant subunit vaccine, which has two vials, both of which come packaged together, and both of which must be stored in the refrigerator because one vial contains the adjuvant. The other vial contains the vaccine antigen. And both vials are critically important, so they have to be stored in that way.

PAUL AUWAERTER: So, Deanna, what other features do you feel are important for clinicians who are going to administer this?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: As with any vaccination, you have to monitor temperature and know your expiration dates and how you're documenting all those things with your staff. So, making sure that they can accommodate another shelf in the refrigerator with those vaccines is important, as well as recognizing those differences, particularly if you were previously giving the live vaccine.

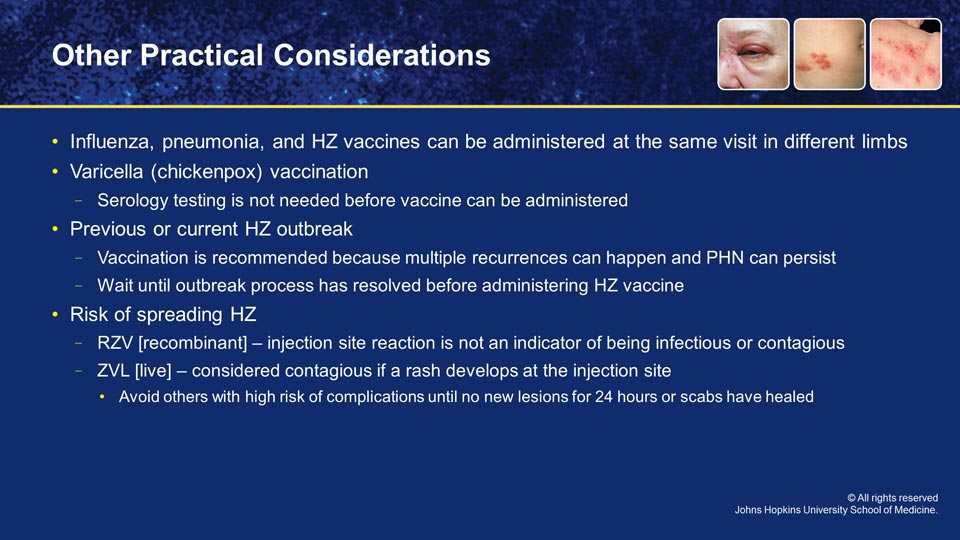

But the big thing is, too, is again, utilizing those preventive care visits has a chance to provide all of the vaccinations that you can. So it is absolutely possible to get the flu vaccine, the pneumonia vaccine and the shingles vaccine all at the same time, just in different limbs.

They are IM injections. So as long as you're giving them in different body parts, that's the only thing you'd really have to pay attention to.

PAUL AUWAERTER: What are some of the other questions, Deanna, that you find frequently come across in the office from the patient?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: So, some patients do not recall if they had chickenpox or not, and so they say, "Well, I'm not really sure if I had chickenpox. Should I still get the vaccine?" In the United States, if you're born before 1980, it is presumed that you had had varicella infection at some point, just because it was so prevalent at that time.

There is no need to do serology testing, but if you've done serology testing and it does not show that they're immune to varicella, you can give the varicella vaccine. But if you've already given the first dose of a shingles vaccine, that's okay. You don't have to go back and provide a varicella vaccine.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Deanna, one of the questions that often come up is someone has had zoster, and should they get one of the new immunizations, or the old immunization?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: Sure. It's always a good question, if I've had a disease process, why would I need to be immunized against it? But it is still the recommendation, because, as we've mentioned, you can get the disease multiple times, and also, that reduction in postherpetic neuralgia and the other complications that can persist.

Now, the thing is when to get it. There is no concrete recommendation about how long after the infection you should get the vaccine. As it is a recombinant vaccine, it's not live, it should not reactivate it for you. But in general, it's recommended that your disease process has resolved.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Excellent points. Some patients are always very nervous that they may make someone else ill if they get a vaccine. So, Deanna, with the new recombinant vaccine, is the risk of someone acquiring an illness different than the live attenuated vaccine?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: It actually is, which is another important point to make patients aware of. Having the sore arm does not mean that you're infectious or contagious in any way. And with the recombinant vaccine, you're not going to actually have the disease process. It's just building that immune response. And that's in contrast to the live vaccine, which, if you develop the sore arm, again, not contagious, but if you did develop a rash, that was considered contagious.

And just like having a shingles outbreak by itself, you are considered contagious until you have no new lesions for 24 hours, and all your current lesions are scabbed over. So that same recommendation would be, if you get the live vaccine and develop a rash, no contact with others that are potentially at high risk for complications -- so younger individuals, people in hospitals, nursing homes or that are immunocompromised themselves -- until the lesions are resolved.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Michael, is there anything else that you find people ask about frequently?

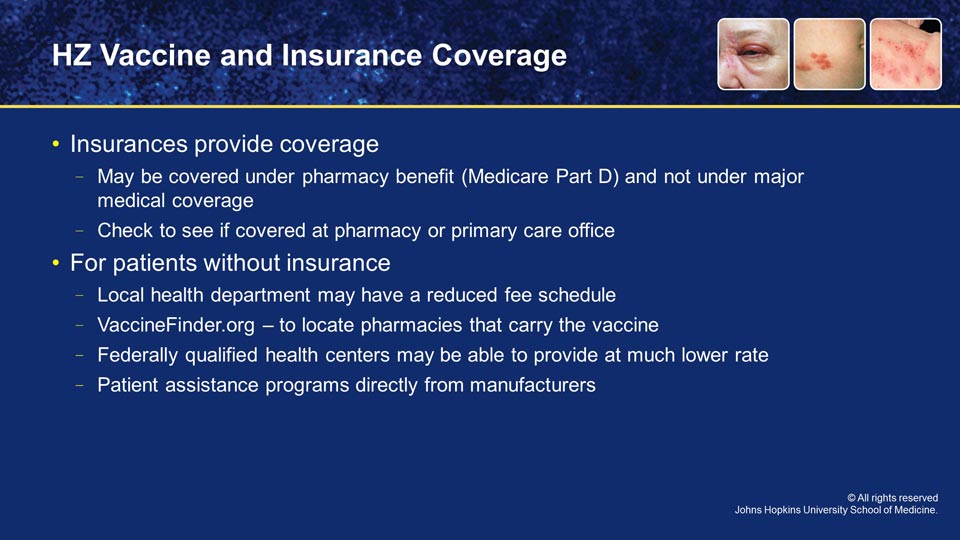

MICHAEL HOGUE: Well, the most common question that I think gets asked by patients in both pharmacies and in primary care offices is, "Will my insurance pay for this vaccine?"

And the answer to the question is, yes. However, it might be covered under the pharmacy benefit and not under the major medical coverage, so it may be more difficult for the patient to find coverage for the vaccine from, for example, their primary care physician's office or from their nurse practitioner or physician assistant.

What they may find is that it's easier to get payment or coverage for their vaccine from the pharmacy under either their Part D benefit or other drug benefit.

So it's important to say, "Well, it may not be covered here, but we can check and see if it's covered at your pharmacy, and vice versa." There is coverage for the vaccine across the board that's provided. Figuring out whether it's covered on the drug benefit side or the medical benefit side may take a little bit of checking.

PAUL AUWAERTER: That's one of the things I think a lot of patients are quite unaware of, and a little bit challenging because clearly any ACIP recommendations have resulted in a mandate that any insurance must cover them. But you can get into some of these difficulties with the details.

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: And then there's always that patient that doesn't have insurance. And so, you know, cost-prohibitive for getting a vaccination. So checking with the local health department, they can often get them on a fee schedule, or using Vaccine Finder to find which pharmacies are actually carrying the vaccine in your area can also be helpful.

MICHAEL HOGUE: And so we've also found that some federally qualified health centers can access vaccine at a much lower rate, as well. And so those are other points of entry in order to be able to access the vaccine. And the manufacturers do have patient assistance programs available for these vaccines.

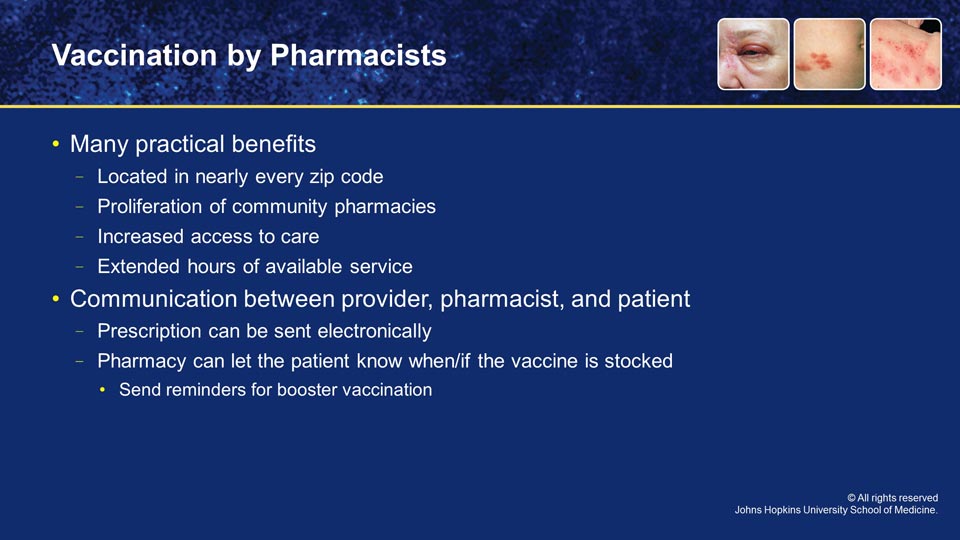

PAUL AUWAERTER: Michael, compared to years ago, all states now allow pharmacists to offer vaccines to patients. Tell me something about these trends and what's your feeling on how this has changed medical care?

MICHAEL HOGUE: Well, pharmacists are located in nearly every ZIP code in the United States. The one thing that's happened over many years is the proliferation of community pharmacies. We see them on just about every corner in every small town, and so access to care is a really big deal.

In some rural communities with shortages of primary healthcare providers, the pharmacist might be the only person available to be able to provide prevention activities in a local community, including vaccination. So it's for this reason that the states have embraced pharmacists being involved in immunization practice to provide better access to underserved communities.

Nearly 95% of the U.S. population lives within 5 miles of a pharmacy, and we have quite a bit of data that shows that patients do frequently access pharmacies for immunizations after normal hours, after the normal hours that clinics would be open. And so that tells us that that convenience factor is in fact having an impact on immunization rates and numbers in local communities.

PAUL AUWAERTER: And, Deanna, with the pharmacists taking, I think, an increasing role in this, how does that translate to medical practices?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: That communication aspect is one of the bigger things. While a patient does not need a prescription to get an immunization, such as shingles, it is very helpful to have that communication between provider, pharmacist and patient that I'm expecting them to get this vaccine. You can either give them a written prescription, or even electronically send the prescription.

Then, too, the pharmacy can contact the patient and say, "Hey, it's in stock, that sort of thing as a nice follow-up, as well as confirmation of lot number, expiration, that they received it.

And then, again, that communication between the pharmacist and the prescriber as far as when that booster vaccination is required. And that can be a nice way to sort of tie things together for the patient, as well as the prescriber and pharmacist.

MICHAEL HOGUE: That's a great opportunity, I think, for the healthcare professions to work together and to provide sort of an immunization community, so to speak around the patient.

We can let each other know on both sides of the medical provider side as to when patients are getting immunized, and we can continue to advocate so that when a patient may say no at one healthcare encounter, the next healthcare professional may in fact have great success at advocating with the patient to be immunized. So I think that is a win-win for everybody, to have everybody involved in that in the immunization process.

But I'd also just like to say that we're very proud that nationally, community pharmacies are significantly contributing to immunization registries. Now, unfortunately, the medical record systems and the dispensing systems in local pharmacies may not always allow the pharmacist to be able to check the IIS prior to immunizing a patient.

We do know that over 80% of the national large pharmacy chains are dumping their immunization data into state immunization registries now. And so that is a positive move in the right direction, which, again, will help us facilitate better communication about the patient's immunization status in the future.

PAUL AUWAERTER: I think when I have patients, many of them know I'm going to say, "Have you gotten your influenza immunization?" And so often they're conditioned, especially in the fall and early winter, that it's an opportune time, especially, to address other immunizations. And I know I go to pharmacies, and I see signs that, you know, have said, "Have you gotten your flu shot? Have you gotten your shingles vaccine?"

So I think the partnerships that you speak of are helpful, as well as the interconnectedness of the electronic records that hopefully should get better over time.

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: I do think, too, that the pharmacists are always such a good backup of, you know, "Did you know your patient was also taking this?" And so when we're talking about immunocompromised status, sometimes patients aren't comfortable sharing all the disease processes that they're dealing with or they just weren't aware that that was something a provider needed to know.

And so the pharmacists, if they're filling those prescriptions, can offer that double-check of saying, "Hey, I know you prescribed this medication or this immunization. Did you know that they were also taking this?" just as another stamp of approval.

MICHAEL HOGUE: I do think another very important point as it relates to both pharmacists and other healthcare professionals that are involved with immunization, there are so many things that press on our time these days in the healthcare system. We have many different demands, whether it's quality measures or payer demands, electronic medical record documentation, and there's a consistent press of our time.

And the one thing I can say is that with certainty, patients are largely unaware of their need for vaccine. Adult patients tend to not know that they're at risk for various infectious diseases and including their risk for shingles. And so it's really incumbent upon us as healthcare professionals to be more proactive.

As a historical perspective, all of us as healthcare professionals have kind of reacted. If a patient walked in and asked for a shingles vaccine, we'd gladly give it to them. But we forget sometimes that with these infectious diseases, we have to proactively advocate with our patients for their need for vaccination.

And sharing information between pharmacies and other healthcare provider locations is really an important step in ensuring that we all take a more proactive role in advocating with our patients.

PAUL AUWAERTER: Deanna and Michael, what should be a key take-home point from some of this recent data that we know about zoster prevention?

DEANNA BRIDGE NAJERA: I think it can be difficult to go through all the data and sort of pick out those key points. But the biggest thing is the efficacious nature of the newest recombinant subunit vaccination, as well as the length of time that that is staying in your system. You get that second booster, and you're good, whereas with the live vaccine, there was that waning efficacy.

PAUL AUWAERTER: And Michael, are there some practical points that you think, especially from a pharmacy perspective?

MICHAEL HOGUE: Well, first of all, I think everyone who's listening to the program needs to understand that it's most likely that the vaccine's going to be paid for when the patient receives the vaccine at the pharmacy.

So the way we can facilitate that process is actually threefold. In many states, pharmacists don't have to have a prescription from a prescriber to be able to provide vaccines in their pharmacy, but in some states they do.

When a prescriber does, however, provide a prescription, that is a mental cue to the patient that this is something we want you to have in the healthcare system, and then that allows the pharmacist to then reinforce the message that the prescriber has given to the patient of the importance of vaccination. And again, you can work in a team environment when that is occurring.

So we would encourage prescribers to prescribe the vaccine even if the pharmacy doesn't have to have a prescription, because it sends a mental note to the patient that vaccination is important, and everybody on my healthcare team is advocating for me to be immunized.

PAUL AUWAERTER: I want to thank both of our expert faculty, PA Deanna Bridge Najera and Dr. Michael Hogue for their helpful insights and expert discussion.

I practice both primary care and infectious diseases. I routinely see the terrible problems that arise from herpes zoster in my patients that can persist for years, as well as even more serious complications needing hospitalization.

For our growing and aging population, herpes zoster will be seen more frequently, harm more patients, and also place considerable burdens on our healthcare system. Over 1 million cases of shingles occur annually, yet the majority of adults who can receive immunization do not do so.

Significant geographic and racial disparities exist, and clinicians should take steps to lessen this burden across all adults to prevent this sort of infection in anyone over the age of 50.

In light of the identified gaps in practice surrounding shingles vaccine, educational initiatives such as this program try to improve care with these high numbers of zoster cases in an aging population, clinicians ought to remain mindful of risk factors, disease burden and also the morbidity.

By adopting approaches to improve vaccination rates, benefits will most certainly accrue. Since the ACIP recommendations were updated in 2018, clinicians should review relevant efficacy and safety data of available vaccines and the practical differences between them.

Lastly, clinicians should understand the advantages of pharmacy-based immunization and work together with pharmacists to support their role as both educators and immunizers. Together, these strategies should increase the numbers of patients who are appropriately vaccinated to prevent zoster and ultimately reduce the high morbidity associated with this disease.

References

- Cohen JI. Herpes Zoster. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):255-263.

- Ogawa R. Keloid and Hypertrophic Scars Are the Result of Chronic Inflammation in the Reticular Dermis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(3).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccination Coverage Among Adults in the United States, National Health Interview Survey, 2016. February 2018. Accessed at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/pubs-resources/NHIS-2016.html

- Lu P-J, O’Halloran A, Williams WW, Harpaz R. National and State-Specific Shingles Vaccination Among Adults Aged ≥60 Years. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):362-372.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccination Coverage among Adults in the United States, National Health Interview Survey, 2017. May 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/pubs-resources/NHIS-2017.html

- Schmader KE, Levin MJ, Gnann JW, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of herpes zoster vaccine in persons aged 50-59 years. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(7):922-928.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A Vaccine to Prevent Herpes Zoster and Postherpetic Neuralgia in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2271-2284.

- Lal H, Cunningham AL, Godeaux O, et al. Efficacy of an Adjuvanted Herpes Zoster Subunit Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(22):2087-2096.

- Cunningham AL, Lal H, Kovac M, et al. Efficacy of the Herpes Zoster Subunit Vaccine in Adults 70 Years of Age or Older. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1019-1032.

- Schmader KE, Oxman MN, Levin MJ, et al. Persistence of the Efficacy of Zoster Vaccine in the Shingles Prevention Study and the Short-Term Persistence Substudy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):1320-1328.

- Izurieta HS, Wernecke M, Kelman J, et al. Effectiveness and Duration of Protection Provided by the Live-attenuated Herpes Zoster Vaccine in the Medicare Population Ages 65 Years and Older. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(6):785-793.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What everyone should know about Zostavax. January 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/public/zostavax/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What everyone should know about Shingles Vaccine (Shingrix). January 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/public/shingrix/index.html

- Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(3):103-108.

- APhA Immunization Center. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.pharmacist.com/immunization-center

Back Top