ADVERTISEMENT

Introduction to the Basic Principles of Ethical Conduct

INTRODUCTION

What makes actions good or bad, right, or wrong? What constitutes an ethical problem? How do health care providers decide the “correct” thing to do when serving patients? Defined as the science that deals with the right or wrong of human conduct and the consequences of those actions, ethics is concerned with what is good for both individuals and society. It affects how people make decisions and lead their lives.1 Just as humans are hard-wired with the potential to maintain the functions necessary for everyday life (e.g., breathe, see, hear, walk, talk, etc.), we arrive with the potential to consider how our actions impact people and world around us.2 To think ethically, a person must understand that he or she can harm others.2 Regardless of how other people behave, we have an ethical duty not to cause others harm or inflict suffering. This duty is emphasized in the responsibility we assume as health care providers to put the needs and safety of our patients first.

Although law often incorporates ethical standards to which most citizens subscribe, being ethical is not the same as following the law. Nor is it the same as doing “whatever society accepts.” In any society, most people accept standards that are, in fact, ethical but sometimes standards of behavior in society can deviate from what is ethical. This activity will differentiate ethics from law, economics, and religion. It will also help participants establish a list of their own personal and professional values in an attempt recognize how those values influence the ethical decisions they make in everyday practice.

HISTORY OF ETHICS IN MEDICINE

After the Second World War, the Nuremberg trials revealed terrible abuses, called “medical experimentation,” perpetuated by Nazi physicians and scientists on concentration camp prisoners. As a result, the Nuremberg Code formulated in 1947 in Nuremberg, Germany, established rules to protect human subjects in medical research.3 These rules merged the physician-centered duties stated in the Hippocratic Oath and the human rights protection. 3 The Nuremberg Code’s text protects the rights of patients/subjects and their autonomy. 3 Those protections affirmed 2 important rights including that of informed consent and the right to withdraw from research.3 Since that time, the Code’s informed consent requirement is now an ethical necessity not only in research but in treatment.3

After the Nuremberg Code, more ethical dilemmas were recognized in the United States (U.S.). With the advent of hemodialysis in the early 1960s, there were many more candidates than hemodialysis machines. As a result, dialysis was rationed. Determination of selection of patients for hemodialysis was ultimately recognized as an ethical dilemma regarding the criteria to select suitable candidates. Some hemodialysis centers allocated treatment based on medical suitability and the patient’s perceived social worth.4 The use of social worth criteria for rationing dialysis in those early years was criticized as being unfair, unequal, and unjust. 4 Based on public outcry about unfair distribution of resources, the federal government established the U.S. End Stage Renal Disease Program, mandating Medicare coverage for dialysis patients regardless of age or ability to pay.4

Later, an associated press story exposed research carried out over several decades by the U.S. Public Health Service in Tuskegee, Alabama, on hundreds of black men with known syphilis.5 In this study, conducted without informed consent, the researchers never offered subjects penicillin so they could study the progression of untreated syphilis.5 This led to acknowledgment of physician bias, racial arrogance, and unethical treatment of racial minorities in the U.S. The Tuskegee Health Benefit Program was established to provide all necessary medical care for the study’s survivors and their wives, widows, and children. In 1997, President Clinton issued a formal presidential apology for the study.5

By the 1970s, several court cases arose concerning patients in a persistent vegetative state. In persistent vegetative states, the brain stem, which controls various functions such as wake/sleep cycles, breathing, and pupillary responses, is still functioning but higher levels of functioning such as meaningful interaction with the environment permanently cease to function.6 These cases raised questions of the ethics surrounding the withdrawal of ventilator, hydration, and nutrition in non-autonomous patients (i.e., those without decision-making capacity).6 A landmark ruling in the 1970s became the first to permit a legally-authorized surrogate to refuse life sustaining treatment on behalf of an incompetent patient even if the patient would die as a result.6 In the years to follow, legal rulings based on the right to withdraw artificial hydration and nutrition, even if the patient died as a result would create significant controversy including a statement from the Catholic Church to protest the removal of feeding tubes.6

By 1974, Congress established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research to recommend policies that would guide the design of ethical research.7 Out of this Commission, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare published The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research.7 The Belmont Report asserted 3 general principles required in research including the following7:

- The requirement to acknowledge autonomy and the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy

- The obligation to do no harm, maximize possible benefits, and minimize possible harms

- The need to treat all subjects fairly and equally regarding distribution of benefits and burdens of the research

To apply these 3 principles, this report mandated that all research must include informed consent, assessment of the study’s risks and benefits, and fair procedures and outcomes in the selection of subjects.7 These principles and other laws related to ethics in research have been historically important to our society. They hold researchers accountable for their actions, allow for the public to place its trust in the research, and promote the moral principle of doing no harm to others.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ETHICS AND MORALITY

The words ethicsand morality are often used interchangeably but distinguishing between the 2 is important. Many people think of morality as something that’s personal, whereas ethics is the standard of “good and bad” distinguished by a certain community or social setting.8Morals are usually learned from family and community as a function of particular cultures and internalized during childhood with little reflection.9 Both terms are used to indicate a fine line between what activities should be considered right and wrong.

Moral people act a certain way because they believe in something being right or wrong. Ethical people act the way they do because society says that is the right thing to do. Consider this example to understand the difference between the 2 terms better. The ethical person knows it is wrong to cheat on a test, whereas the moral person would not actually cheat on the test. Table 1 outlines the basic differences between the 2 terms.

| Table 1. Morality and Ethics8,10 |

| Root of Difference |

Ethics |

Morality |

| Definition |

Rules of conduct that govern specific individuals or groups |

Values that are shared by communities |

| Influences |

Factors that are legal and professional |

Social and cultural factors |

| Perspective |

Society’s perspective |

Personal perspective |

| Consistency |

Generally uniform no matter the setting |

They differ from one society to the other and across cultures |

| Religious connotation |

No |

Yes |

DEFINING VALUES AND VIRTUES

Values are the motivational drives behind one’s actions.2 They guide what is the “right” thing to do. They are the standards that form the foundation of an individual’s character, shaping personality, attitudes, and behavior.2 Virtues are similar to values, but actually represent an authority’s perception of which values are most important and how these values must be manifested.11 These virtues are the personality traits that one’s community encourages and are manifested in the role models that communities put forth.11 Organized religion is an example of a system based on virtues. Churches dictate the rules that one must live by and the specific behaviors that allow one to be in accordance with the rules, such as the Ten Commandments for Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. The most significant distinction is that a virtue requires the approval of others while living by one’s values does not. Table 2 lists some common virtues.

| Table 2. Common Virtues2,11 |

| Virtue |

| Commitment |

| Compassion |

| Cooperation |

| Fairness |

| Forgiveness |

| Generosity |

| Gratitude |

| Honesty |

| Integrity |

| Loyalty |

| Self-control |

| Trust |

The following exercise will help participants determine their personal and professional value system. Various activities help people identify their values; this is just one example of a values exercise adopted from Taproot (http://www.taproot.com/archives/37771). Once individuals establish a set of values, it’s easier to make choices that best reflect those values. Being able to clearly articulate one’s values will allow a justified explanation of the choices made in difficult ethical situations.

Exercise 1. Identifying Your Values12

As you read through the list, write down the words that feel like a core value to you personally. Feel free to add any that are not listed.

| Abundance |

Freedom |

Selflessness |

| Acceptance |

Fun |

Spirituality |

| Accountability |

Generosity |

Stability |

| Achievement |

Growth |

Success |

| Adventure |

Health |

Teamwork |

| Advocacy |

Honesty |

Thankfulness |

| Ambition |

Humility |

Thoughtfulness |

| Appreciation |

Humor |

Traditionalism |

| Attractiveness |

Inclusiveness |

Trustworthiness |

| Autonomy |

Independence |

Understanding |

| Balance |

Individuality |

Uniqueness |

| Boldness |

Innovation |

Usefulness |

| Brilliance |

Intelligence |

Versatility |

| Calmness |

Joy |

Vision |

| Caring |

Kindness |

Warmth |

| Challenge |

Knowledge |

Wealth |

| Charity |

Leadership |

Well-Being |

| Cheerfulness |

Learning |

Wholesome |

| Community |

Love |

Willingness |

| Commitment |

Loyalty |

Willpower |

| Compassion |

Mindfulness |

Wisdom |

| Cooperation |

Optimism |

|

| Collaboration |

Originality |

|

| Consistency |

Passion |

|

| Creativity |

Peace |

|

| Credibility |

Perfectionism |

|

| Curiosity |

Playfulness |

|

| Daring |

Popularity |

|

| Decisiveness |

Power |

|

| Dedication |

Professionalism |

|

| Dependability |

Relationships |

|

| Diversity |

Reliability |

|

| Empathy |

Resilience |

|

| Excellence |

Resourcefulness |

|

| Family |

Responsibility |

|

| Friendships |

Security |

|

| Flexibility |

Self-Control |

|

Next, group all similar values together from the list of values just created. Create a maximum of 5 groupings. If you have more than 5 groupings, drop the least important grouping(s). See the example below:

| Cheerful |

Balance |

Acceptance |

| Fun |

Health |

Compassion |

| Humor |

Well-being |

Kindness |

| Joy |

Spirituality |

Love |

Next, choose one word within each grouping that represents the label for the entire group and circle it. There are no right or wrong answers. Choose what most represents you. See the example below – the label chosen for the grouping is bolded.

| Cheerful |

Balance |

Acceptance |

| Fun |

Health |

Compassion |

| Humor |

Well-being |

Kindness |

| Joy |

Spirituality |

Love |

These are your core values. It may be helpful to add a verb to each value to see what it looks like as an accountable core value. For example:

- Seek joy

- Promote balance

- Act with kindness

WHAT ETHICS IS AND WHAT IT IS NOT

It is important to grow ethically and make decisions that best influence the patients and community in which we live. However, we have other obligations to society. This includes following the law, economic considerations for fair distribution of resources, and for some, religion must be considered. In the following section we examine how ethics overlaps these fields and compare and contrast the differences.

Ethics and Law

In highly regulated contexts, health care providers involved in medication therapy often turn to the law for clarification about duties to patients. However, laws should be only one of many points of ethical inquiry. Ethical judgments are independent of regulatory rules and laws.9 The law may allow an action, but that action may still be unacceptable as a matter of ethics. Similarly, an action might be ethically required in a situation but be legally impermissible giving rise to the notion of an “unjust law.”

Ideally, law should respect the demands of ethical obligations but sometimes law and ethics collide. For example, consider the pharmacist who encounters a patient who has run out of a maintenance medication but according to the law it is illegal to dispense a medication without a valid prescription. What is the pharmacists ethical obligation if failing to dispense the medication may harm the patient? The exception to the law would be to permit the pharmacist to dispense a partial refill until the patient can obtain a valid refill from the physician. Prioritizing the patient’s well-being reflects the Pharmacists Code of Ethics; although it is technically not in compliance with legal standards, it is the best course of action.13

Ethics and Economics

Economics grapples with how societies deal with limited resources. This field of study has much to contribute to the development of ethical foundations that determine access, need for valuable health care resources, and the analyses and just distribution of these resources.14 The fact that the primary purpose for consuming health care is to improve health generates specific distributional concerns.14 Should everyone have equal access to the same level of care regardless of ability to pay? Would broad (but not necessarily equal) access to health care services by all members of society be considered a just policy? Should the funding be solely limited to private parties or should health care be financed through a public institution? Both economic analysis (arrangements for financing health care resources) and ethical analysis (justified allocation of resources) are necessary to consider the just and fair allocation of health care resources.14

Ethics and Religion

Religion is defined by the First Amendment as, “a comprehensive belief system that addresses the fundamental questions of human existence, such as the meaning of life and death, man's role in the universe, and the nature of good and evil, and that gives rise to duties of conscience.”15 Religions typically believe that their faith represents a path to enlightenment and salvation providing the members with a set of guidelines to follow in accordance with specific religious doctrines. By contrast, ethics are universal decision-making tools that may be used by a person of any religious persuasion, including atheists.

There is a spectrum of views about how religion and ethics are related. Some would argue that religion is the cornerstone of ethics and without religion there would be no understanding of what is “right or wrong” and therefore ethics would not exist. Others believe that one can maintain ethical perspectives and subscribe to ethical principles and behavior without engagement in religious beliefs, institutions, or practices. In health care, the line between ethics and religion can become blurred and often controversial.

What are a health care provider’s ethical rights and obligations when patients request a legal medical procedure to which the clinician objects for religious or ethical reasons? These procedures may include administering terminal sedation in dying patients, providing abortion or emergency contraception therapies for failed contraception, or prescribing birth control to adolescents without parental approval. These are circumstances where religion and ethics can collide. States have passed laws that shield physicians and other health care providers from adverse consequences for refusing to participate in medical services that would violate their consciences, known as conscience clauses.16 For example, the Illinois Health Care Right of Conscience Act protects a health care provider from all liability or discrimination that might result as a consequence of refusing to participate in a form of health care service that is contrary to a health care provider’s conscience.16

Critics of the conscience clause opine that patients may be denied legally and medically permitted medical interventions based on a provider’s personal ethical beliefs or religious obligations. Regardless of viewpoints, many ethical issues must be considered when clinicians cite religious beliefs. They must balance the duty to prioritize the patient’s well-being and practice according to each profession’s code of ethics.

KOHLBERGS STAGES OF ETHICAL DEVELOPMENT

Throughout life people develop in their capacity to make decisions and judgments that are ethical and to act in accordance with such judgments. Lawrence Kohlberg is known for his theory of ethical development based on Jean Piaget’s theory of ethical judgment for children.17 He identified 6 stages of ethical judgment, arranged in levels of complexity, which were then classified into 3 general levels.17 At level 1, the preconventional level, ethical choices are externally controlled. 17 In other words, choices are made based on consequences (e.g., punishments or rewards). At level 2, the conventional level, conforming to social rules remains important, however emphasis shifts from self to relationships with others. 17 At level 3, the postconventional stage, individuals move beyond their own relationships to what is good for society as a whole.17 Table 3 identifies each individual stage correlated with the specific decision making level.

| Table 3. Kohlberg’s Stages of Ethical Development17 |

| Level 1: Preconventional Level |

Level 2: Conventional Level |

Level 3: Postconventional Level |

| Stage 1: Punishment/obedience orientation (choices based on punishment) |

Stage 3: Good boy/nice girl orientation (behavior is determined by social approval) |

Stage 5: Social contract orientation (considers alternatives when laws and rules are not consistent with individual rights and interests of the majority) |

| Stage 2: Instrumental purpose orientation (choices based on a reward or satisfying personal needs) |

Stage 4: Law and order orientation (considerations beyond close relationship with others; looks at a bigger picture; social rules and laws determine behavior) |

Stage 6: Universal ethical principle orientation (considers perspective of every person that could be affected by the decision; appropriate action is determined by one’s self-chosen ethical principles of conscience) |

It’s important to note that the later stages don’t replace the earlier stages.17 They add another way of thinking about right and wrong, but even adults will often act out of a desire to abide by social norms, to receive a reward, or to avoid punishment. Cross-sectional data have shown that every individual progresses through the same sequence of development; however, the rates of development will vary.17 Some individuals may never reach stage 6, the highest level of ethical functioning.17

RANGE OF ETHICAL CHOICES

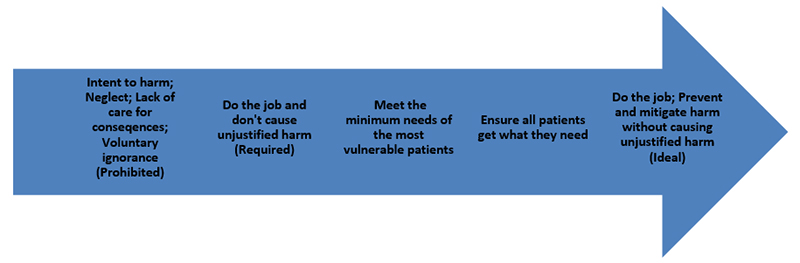

Some people think of ethical choices as purely right or wrong when actually there are a range of choices one can make.2 Bernard Gert, a philosopher known for his work in medical ethics, has described 4 categories of ethical choices that can be viewed on a continuum2:

- Ethically prohibited actions are actions that are wrong

- Ethically required actions are those that follow directly from a person’s role-related responsibilities (e.g., professional responsibilities)

- Ethically ideal actions occur when a person meets his or her role-related responsibilities; avoids causing unjustified harm; and acts in a way that promotes the good by preventing, mitigating, or addressing harms that have been caused

- Ethically permitted actions range on the continuum between those that are required and those that are ideal

Decisions made in these categories are not right or wrong except if they are ethically prohibited. Various characteristics make some choices ethically prohibited such as those that cause unjustified harm or that involve unjustified neglect of role-related responsibilities. Doing the job without causing unjustified harm is the minimum requirement of all employees. Meeting the needs of the most vulnerable to ensuring all patients receive what they need falls in the spectrum between required actions and ideal actions. Figure 1 is a schematic drawing of the range of ethical choices.

Figure 1. Range of Ethical Choices2

Case Example: Forgot to Fax

A patient comes to the pharmacy to pick up refills. The pharmacy technician remembers taking a phone call from the patient earlier in the day asking her to fax the physician for a refill. The pharmacy technician was busy and forgot to fax the order to the physician. She decides to tell the patient the physician has not responded to avoid an angry confrontation with the customer and being reprimanded by the pharmacist for not fulfilling her job responsibilities. Which ethical choice is this?

Answer: This is an example of an ethically prohibited action due to the pharmacy technician’s neglect of role-related responsibilities.

Case Example: Out-of-date Ingredients

A pharmacy technician compounded a prescription for an estrogen cream and noted that one of the ingredients she used was out of date by one month. The pharmacist did not catch that when he checked the prescription. The technician reasoned that one month probably would not make a difference and why waste the inventory? She decided not to tell the pharmacist and dispensed the medication. This is an example of which of the above ethical choices?

Answer: This is an example of an ethically prohibited action due to the pharmacy technician’s lack of care for the consequences of selling an expired medication. It could possibility harm the patient.

Case Example: Refusal to Sell Plan B

A patient comes to pick up pain medication from a hospital outpatient pharmacy and tells the pharmacy technician she was just in the emergency room due to injuries from an assault and wants to purchase Plan B. She has very little income and was hoping she could buy it here for a better price then her local pharmacy. It is against the technician’s beliefs to use emergency contraception and she was always grateful to work in a place that did not require her to sell the medication. She tells the patient the hospital does not stock the medication and proceeds to call the local area pharmacies to find her the best price. This is an example of which of the above ethical choices?

Answer: This is an example of an ethically ideal action because even though it goes against the technicians own ethical values, the technician avoids causing unjustified harm by turning the patient away. She acts in a way that furthers her role beyond what is required by calling area pharmacies to find the patient the best price on the medication. She ensures the patient’s health care needs are met.

PRACTICING ACCORDING TO ETHICAL PRINCIPLES

Excuses and rationalizations are ways that one may use to deny their ethical responsibility. Pharmacy technicians who use the following statements to justify a behavior should wonder if the action was ethically questionable2:

- “My superior told me to do it”

- “I did not mean to harm anyone”

- “Other employees were doing it”

- “No one saw me do it”

Competent, rational adults cannot pass their ethical responsibility off to another. Good people who are trying to do the right thing sometimes inadvertently cause harm. The fact that causing harm was unintentional might mitigate the level of moral responsibility but doesn’t change the fact that harm was caused. Admitting and mitigating ethical mistakes becomes necessary.

Admitting one’s mistake and remedying the behavior by vowing not repeat that mistake builds ethical growth and competency. Even if others in the workplace are doing the same questionable activity, if the action is ethically prohibited, it is still wrong no matter how many people are doing it. A person with integrity does the right thing even if no one saw the action. Pharmacy technicians who use these excuses to justify unethical behavior should realize they have room for ethical growth and more competent decision making.

Examining the motives behind one’s ethical choices also promotes growth and moral development. The reasons behind the ethical choices people make can be divided into 3 categories: reasons that demonstrate ethical immaturity, those that demonstrate a conventional level of growth, and reasons that demonstrate ethical sophistication.2 These are very similar to Kohlberg’s stages of ethical development. Ethically immature decisions are based on the hope of pleasing others or concerns that there may be a punishment.2

Consider a pharmacy technician who goes out of his way to help a customer in the over-the-counter aisle when his boss is watching, but at other times pretends to be too busy to step into the aisle to assist customers. While the action of taking extra time to help a customer is the correct ethical action, the reason for making the correct ethical choice was made based on ethical immaturity, and the need to please his boss or avoid a reprimand. A transitional stage exists between being dependent on an external authority for approval and realizing one’s own responsibility. This is the conventional level of growth where a person follows rules or peer expectations without much insight into why they follow the rules.2

These rules or expectations may change depending on the group within which people find themselves.2 This may lead to inconsistent behavior. For example, the way one behaves around fellow employees may be very different from behavior when the pharmacy manager is on-site. In this case, there is some growth potential to demonstrate ethical sophistication, otherwise behaviors would be consistent no matter who is present. Ethically sophisticated decisions reflect understanding of the principles that lie behind the rules or expectations.2 Being ethically sophisticated means that it is possible to live to the fullest potential in accordance with a personal value system and make independent choices that express one’s own best self. 2

Tips to live an authentic ethical life:

- Do not deny ethical responsibility

- Admit and mitigate mistakes

- Examine motivations for ethical decisions

ASSESSING ETHICAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Various methods help researchers determine ethical growth and development. Kohlberg’s Moral Judgment Interview is a structured interview requiring trained interviewers and scorers.17 Another instrument developed by James Rest is the Defining Issues Test, the most commonly used assessment method in research studies.17 Both assessments consist of a set of hypothetical stories involving ethical dilemmas that the subject must rank in order of ethical importance. While applicable for research purposes, these assessment methods are not user friendly for individuals who wish to assess their personal ethical growth outside of research purposes. The following an exercise can be used to help determine ethical growth and development.

Exercise 2. Assessing Ethical Growth and Development2

First, state an ethical principle that you generally follow. Try to remember why you first followed this principle. Were you rewarded if you did and punished if you didn’t? Did you feel coerced or intimidated into following it? Describe the circumstances under which you tended to uphold the principle and circumstances when you tended not to uphold the principle. Last, explain why you follow the principle today. If you have trouble tracing your growth from your current level of ethical sophistication back to its source, try it from the other direction.

Find a principle that you were expected to uphold as a new member at your place of employment. Plot the course of your reasons for adhering to it and see where you are today. It may be easier to see the line of development if you think about why you followed some professional principle initially as compared to why you adhere to it now. Let’s look at an example by recalling the pharmacy technician who only helped customers when the boss was watching.

Example: When the Boss Was Watching

When I first started my job as a pharmacy technician, I remember how busy I always was behind the pharmacy counter. I would become irritated when a customer would ask questions or ask for help finding an item in the over-the-counter aisle. I would put on a pleasant smile when my boss was watching and patiently help any customer who asked, but when the pharmacy manager was too busy to notice, I would just point to a particular aisle where I knew the product was located and let customers find it for themselves.

Over time, I began to understand that my job was to put the patient first. I applied the first principle of the Pharmacy Technician Code of Ethics to my everyday interactions with customers which stated, “A pharmacy technician’s first consideration is to ensure the health and safety of the patient, and to use knowledge and skills to the best of his/her ability in serving others.”18 I realized that I was obligated to use my knowledge to ensure that customers could find what they needed regardless of how busy I was. As I became a more seasoned technician, I began enjoying each interaction I had with the customer. I realized not only was I helping the customer but also other colleagues who would have to take the time to help the customer if I refused. While helping others I was also upholding my own personal values of kindness, compassion, and professionalism.

This technician has clearly progressed through the stages of ethical development as suggested by Kohlberg. In the early stage, helping customers was done to avoid punishment from his supervisor (stage 1) which progressed to abiding by the Code of Ethics as the reason behind helping customers (stage 4). As a seasoned employee, the technician considered the perspectives of every person who was affected by his decision including other colleagues. At this stage, the technician was now incorporating his own set of personal values into the ethical decision of helping customers (stage 6).

CONCLUSION

Complying with ethical standards is vital because health care is a profession that impacts the lives of patients and their families. When ethical responsibilities are ignored, those we strive to provide care for may suffer. As the principles that guide moral behavior, ethics becomes paramount in making decisions that are mindful of both professional and legal requirements. The ethical decisions one makes flow from the unique, highly complex set of acquired values. Those values should be balanced with patients’ rights, particularly as they are applied to patient care. The pharmacy technician who embraces a professional practice built upon ethical principles and virtues will be skilled in ethical decision-making as they strive to promote the care, well-being, and safety of all patients.

REFERENCES

- The Free Medical Dictionary. Definition of ethics. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Ethics+(philosophy)

- Elliott D. Ethical Challenges: Building an Ethics Toolkit. AuthorHouse; 2009. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Ethical-Challenges-PDF-1-Elliott-1.pdf

- Shuster E. The Nuremberg Code: Hippocratic ethics and human rights. Lancet. 1998;351(9107):974-977. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60641-1. PMID: 9734958.

- Estes Savage T, Browne T. Dialysis rationing and the just allocation of resources: An historical primer. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/v36b_a4.pdf

- The U.S. Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

- Bernat J. Ethical issues in the persistent vegetative state patient. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.aan.com/globals/axon/assets/6114.pdf

- The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html#xbound

- Grannan C. What’s the difference between ethics and morality? 2021. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/story/whats-the-difference-between-morality-and-ethics

- Fiore RN, Frame TR, Uroza S. Ethical decision making. In: O’Connell M, Smith JA. Eds. Women’s Health Across the Lifespan, 2e. McGraw Hill; Accessed June 25, 2021. https://accessmedicine-mhmedical-com.neomed.idm.oclc.org/content.aspx?bookid=2575§ionid=213569581

- Horner J. Morality, ethics, and law: introductory concepts. Semin Speech Lang. 2003;24(4):263-274. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815580.

- Ethics and virtue. Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. Accessed June 26, 2021. https://www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/ethical-decision-making/ethics-and-virtue/

- Taproot core values exercise. Accessed June 26, 2021. http://webmedia.jcu.edu/advising/files/2016/02/Core-Values-Exercise.pdf

- Code of Ethics for Pharmacists. American Pharmacists Association. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://portal.pharmacist.com/code-ethics

- Hurley J. Ethics, economics, and public financing of health care. J Med Ethics. 2001;27(4):234-239. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.4.234.

- Clements B. Defining religion in the first amendment: A functional approach. 74 Cornell L. Rev. 532 (1989). Accessed June 28, 2021. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3412&context=clr

- Curlin FA, Lawrence RE, Chin MH, Lantos JD. Religion, conscience, and controversial clinical practices. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(6):593-600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065316.

- Sanders, CE. Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development. Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 May. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/science/Lawrence-Kohlbergs-stages-of-moral-development. Accessed 30 June 2021

- Code of Ethics for Pharmacy Technicians. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://thepharmacyprofessionals.com/code-of-ethics

Back to Top