ADVERTISEMENT

Dietary Supplements for Maintaining or Boosting Immunity: What Pharmacists Need to Know (Monograph)

Introduction to the Immune System

The immune system is the body’s biological defense system. It is a complex, multifaceted, and intricate network of specific organs, tissues, cells, proteins, and chemicals that function to protect the host from a range of pathogens and harms/threats.1-4 It is able to distinguish “self ” from “non-self ” pathogens and protects the host from pathogens and other threats.4 Major components of the immune system include white blood cells, lymph nodes, the spleen, tonsils, adenoids, thymus, bone marrow, skin, mucous membranes, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and the genitourinary tract. Each component has a specialized role in defending against antigens that may threaten the body.1-5

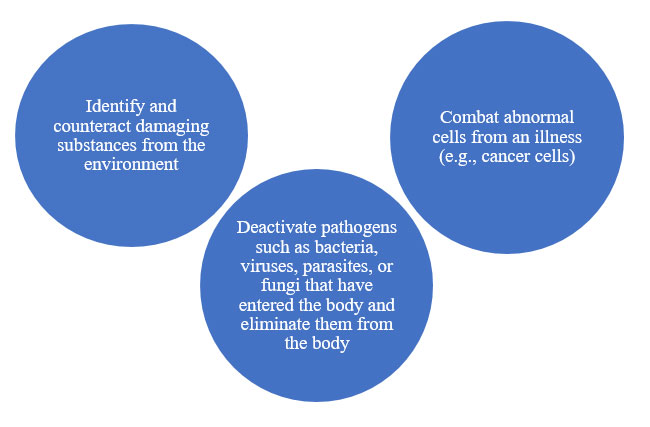

A well-functioning immune system is critical to overall survival. It provides an exclusion barrier that detects and eliminates pathogens that cause disease, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites that exist in the environment.1-4 The immune system also identifies and endures nonthreatening causes of antigens and sustains an immunological memory of these occurences.1-4 Furthermore, the immune system detects, protects, and destroys abnormal cells that originate from host tissues such as cancer cells1-4 and helps mend damage from external factors, including environmental pollutants and innate toxins (Figure 1).6-10

| Figure 1. Key Functions of the Immune System6 |

|

Research has established that there is a fundamental relationship between one’s dietary habits, nutritional status, lifestyle factors, and the function of their immune system. This activity will examine this relationship with a discussion of the immune system, the role of nutrition in maintaining a healthy immune system, and recommendations for how to boost immunity.

Layers of the Immune System

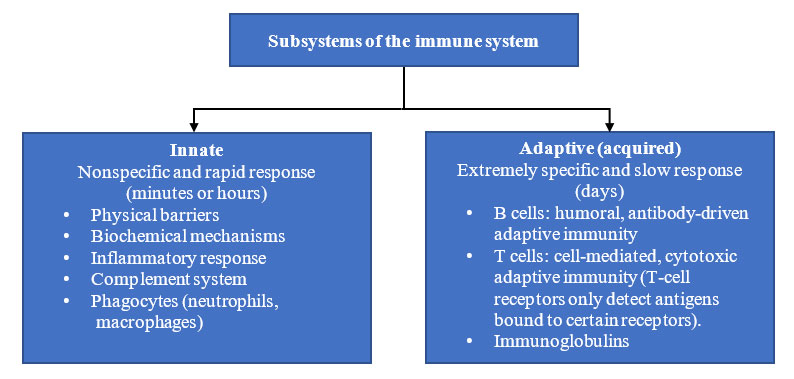

There are 2 subsystems of the human immune system: the innate immune system (nonspecific) or the adaptive (specific) immune system (Figure 2).1-7,11,12 Both systems work in conjunction with one another to protect the host organism from infection, disease, and other threats.1,5,6 The innate immune system is the first line of immune defense and delivers a swift response, whereas the adaptive immune system is slower to respond to specific abnormal cells or microbes.1,5-7,11

| Figure 2. Subsystems of the Immune System6,7,12 |

|

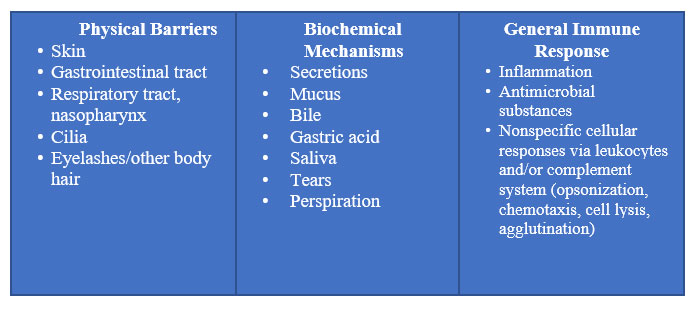

The immune system is incorporated into all physiological systems and safeguards the body against infections and other external and internal harms using 3 distinguished levels of protection, depending on the nature of the threat 8:

- Physical (e.g., skin, epithelial lining of the GI and respiratory tracts) and biochemical barriers (e.g., secretions, mucus, and gastric acid) (Figure 3)5,7,8

- Numerous distinct immune cells (e.g., granulocytes, CD4 or CD8 T and B cells)

- Antibodies (i.e., immunoglobulins)8

| Figure 3. Physical and Biochemical Barriers5,7,8 |

|

Innate Immune System

As the first-line barrier of defense in the immune system, innate immunity activates and exerts a rapid-response mechanism to recognize and abolish any threats, characteristically via inflammatory processes; it then resolves the inflammation and repairs the damage triggered by these events.1,7,12 Innate immunity, also known as genetic or natural immunity, refers to immune responses that are present from birth and not learned, adapted, or refined as a result of exposure to microorganisms/antigens.1 Regardless of how often an infectious agent is encountered, an innate immune response is triggered.12 The innate immune system includes physical barriers that help prevent the entry of pathogens through the eyes, skin, mucus membranes, and epithelium of the gut; a host of immune cells; and the complement system.1,5,7,13-15 The cells of the innate immune system, which include phagocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, are vital to the body’s defenses as they neutralize pathogens and assist with the adaptive immune response.1,5,7,13-15

Adaptive Immune System

The second line of defense is referred to as the adaptive immune system (also known as the acquired immune system). If the innate immune system is unable to destroy the offending pathogen and/or foreign or abnormal cells, the adaptive immune system is activated and targets the pathogen precisely by recognizing the antigen.12 The adaptive response includes antigen-specific cells, such as T lymphocytes, subsets of which harmonize the overall adaptive response or execute virally infected cells, and B lymphocytes. It can be activated to secrete antibodies that are specific to the infecting pathogen.16,17 Although the adaptive immune system is slower to respond than the innate system, it is responsible for creating immunological “memory”, which provides a robust, quick antigen-specific response to a recurrent infection with the same pathogen.16,17

Factors That May Impair or Weaken the Immune System

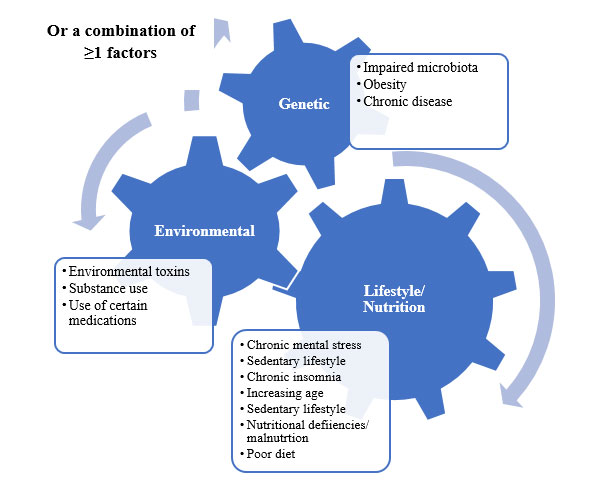

A robust and well-functioning immune system is essential to maintaining overall good health and well-being. Immunological function depends on many factors that can either maintain and/or strengthen its function or impair it.18 These factors can be categorized as genetic, environmental, lifestyle and nutrition, and/or the interaction of 1 or more of these factors.18 Examples of these factors include chronic stress, lack of sleep and/or sleep disorders, increasing age, poor diet, environmental toxins such as pollution and tobacco use, being overweight/obesity, certain medical conditions, and the use of pharmacologic agents such as corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, or immunosuppressive agents that are often prescribed to prevent organ transplant rejection and to treat autoimmune disorders and immune-mediated diseases (Figure 4).19-22

| Figure 4. Factors That Weaken or Impair the Immune System19-22 |

|

Stress and Immune Health

According to the American Psychological Association, stress can reduce the number of NK cells or lymphocytes in the body, which in turn diminishes the body’s capacity to combat viruses and other infections.23 A meta-analysis revealed that even a few days of stress can impact the immune system. More importantly, chronic stress may reduce the adaptiveness of the immune system, particularly in older individuals and those with other illnesses, which makes these patient populations more prone to immune system impairment.24

Sleep and Immune Health

Unfortunately, many individuals, including health care providers (HCPs), underestimate the direct correlation between adequate sleep and overall health and its impact on the immune system. A recent study indicated that nearly 33% of adults in the United States do not get the recommended number of hours of sleep.1 A recent report also revealed that inadequate sleep is associated with deficiencies in vitamins A, C, D, and E, and essential trace elements such as zinc; this also implies that these nutrients have various important roles in the multiple systems that support immune health.1,25 Studies have also revealed that chronic insomnia is linked to an increase in inflammatory markers and has a strong association with adverse effects on immune function and overall health.22 Other studies reveal that sufficient sleep can aid in maintaining the functions of both the innate and adaptive immune systems, as well as improve the function of T cells.22,26

Aging and Immunity

Research indicates the aging process contributes to reduced efficiency of the immune system with regard to its ability to maintain an effective response and also causes noteworthy and multifaceted changes to both the innate and adaptive immune systems, a phenomenon which is commonly referred to as immunosnescence27-28 The most prominent effects of immunosenescence includes thymic involution and reduced number and function of T and B cells. Additionally, the number of memory T and B cells increase, but their response to new antigens decreases. The functions of granulocytes, monocytes and NK cells are also reduced. Research also shows that undernutrition which is very prevalent among elderly individuals is associated with an increased risk of being immunocompromised.28

Nutrient Deficiencies and Immune Health

It is well documented that nutritional status is strongly correlated with overall immunity and the host’s ability to resist infection. Certain nutrients have critical roles in regulating the immune system, are crucial for immune cell function, protect the human body against oxidative stress, and are involved in the production of antibodies.1,7,18,25 These include micronutrients such as vitamins A, C, D, and E and the trace element zinc.1,7 Undernutrition due to insufficient consumption of essential micronutrients may weaken the body’s capacity to support innate immune responses.1,12

Tobacco and Immune Health

Tar and nicotine have immunosuppressive effects on the innate immune response and tobacco products containing high concentrations of tar and nicotine cause the greatest immunologic changes. For instance, cigarette smoke altogether suppresses or decreases neutrophils phagocytic activity and affects chemotaxis, kinesis, and cell signaling. It also inhibits the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thus compromising pathogen killing by neutrophils and other cells of the innate immunity.29

Obesity, Other Chronic Medical Conditions and Immune Health

Some research has indicated that obesity may hinder immune function and alter leucocyte counts and cell mediated immune responses.30 According to studies, obesity causes alterations to both local and systemic immune modifications due to metabolic stress.31,32 In a 2020 publication, de Frel et al. indicated that obesity was a common factor in patients with severe COVID-19 infections. They noted that obesity, other chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes and unhealthy lifestyle factors such as alcohol use, poor nutrition and a sedentary lifestyle can impair the immune system and increase risk of severe infections.32

According to a recent publication in the Journal of Diabetes Investigation, researchers conducted a cross sectional study of 49 adults with type 2 diabetes.33 The researchers found that participants with T2DM had a decreased NK cell activity which was related to glucose control compared to those individuals with normal glucose tolerance or prediabetes. The authors concluded that larger studies are warranted to confirm their findings.33

Recent findings also imply that the immune system has a role in the development and the progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD), primarily due to a greater understanding of the inflammatory process involved in the pathology of CVD.34 In a 2020 publication, Fani et al. attempted to determine the exact immune cells involved in the pathogenesis of CVD.35 They repeatedly quantified the number of innate immune cells (granulocytes and platelets) and adaptive immune cells (lymphocytes) to determine the correlation of these cells with the risk of CVD.35 The authors concluded that the risk of CVD was greater among individuals with increased granulocytes over time while the risk of CVD was lower among those with decreased lymphocytes.35 Their findings suggest that greater activity in the innate immune system and lower activity in the adaptive immune system may be correlated with a greater risk of CVD.35 They also noted that more studies were warranted to validate their findings.35

The Impact of Nutritional Deficiencies on Immune System Function and Status of Deficiencies in the United States

As previously noted, a large body of research has shown that nutritional deficiency or inadequacy can impair immune function and weaken the immune response. Growing evidence suggests that increasing the intake of certain nutrients above currently recommended levels may have a positive effect on immune function, modulate chronic inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, and diminish the risk of infection or severity/duration of symptoms.1,7,11,18 Addressing nutrient deficiencies via dietary changes or supplementation can augment resistance to infection and recovery of immunological function.12 Current studies indicate that these beneficial effects are correlated with both macronutrients (lipids such as n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids) and micronutrients (zinc and vitamins C, D, and E).1,7,12,18

Although the importance of maintaining adequate amounts of micronutrients and zinc for a healthy immune system have been recognized, studies show that inadequate nutrient intake is an extensive problem among various age groups in the United States.1,7 A recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (a biannual cross-sectional study of the US population conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) evaluated data from 26,282 adults aged 19 to 99 years. According to the study, 95% of the US adult population had inadequate intake of vitamin D and 84% had inadequate intake of vitamin E.1 Furthermore, 45%, 46%, and 15% of the US adult population had deficiencies in vitamin A, vitamin C, and zinc, respectively.1 These findings indicated that a substantial number of Americans fail to consume the average recommended nutrients, as defined in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which are essential for maintaining a healthy immune system.1,36

Immune-Enhancing Interventions

Nonpharmacologic Options

Because pharmacists are easily accessible, they can be instrumental in educating patients about various nonpharmacologic options (i.e., dietary and lifestyle interventions) that can be incorporated into their daily routine to help maintain or enhance the overall function of their immune system. Addressing the aforementioned factors can enhance the function of the immune system, as well as the patient’s overall health and well-being (Table 1).32

| Table 1. Recommended Dietary and Lifestyle Interventions That May Help Preserve and/or Boost Immune Functions32 |

| Category |

Recommended Intervention |

| Diet |

- Maintain healthy, balanced diet and decrease intake of processed foods, especially refined carbohydrates

- Ensure adequate daily hydration

|

| Physical activity |

- Implement regular exercise into daily routine after discussing appropriateness with primary HCP

|

| Stress |

- Reduce chronic stress and use coping measures for destressing and relaxation

|

| Smoking and alcohol |

- Consider smoking cessation

- Avoid or limit use of alcohol

|

| Sleep |

- Implement sleep hygiene measures into daily routine and establish a bedtime schedule to assist in improving quality of sleep.

- Consult primary HCP if experiencing chronic insomnia and discuss sleep study to rule out sleep apnea diagnosis

- Be compliant with therapy if diagnosed with sleep apnea to improve quality of sleep and to lessen incidence of sleep apnea-related health issues

- The National Sleep Foundation recommends healthy adults need between 7 and 9 hours of sleep per night; individuals aged >65 years should get 7 to 8 hours per night

|

| Miscellaneous |

- Stay up to date with recommended Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices immunizations

- Implement universal infection control measures throughout the day such as routine hand washing with soap and water and/or use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer when water and soap is not available

|

| HCP=health care provider. |

Nonprescription Nutritional Supplements for Boosting the Immune System

Although obtaining essential nutrients from diet is the optimal approach, many individuals find this difficult to do and elect to use dietary supplements to meet their nutritional needs. Dietary supplements are considered a safe and effective means of complementing a healthy and balanced diet to maintain and boost the immune system. There are many nonprescription dietary single entity or multivitamin/multimineral supplements formulated and marketed for the promotion and maintenance of immune health. Immune-boosting supplements may contain 1 or more of the vitamins A, C, D, and E, along with trace elements of zinc and selenium. Some also contain Echinacea, turmeric, ginger, and other herbal ingredients, as well as prebiotics and probiotics. Many other products marketed for strengthening the immune system may contain elderberry.37 Some immune-boosting supplements are formulated to address the specific nutritional needs of patient populations by age group (e.g., children, adults aged ≥50 years) or by gender. They are also available in a variety of formulations including tablets, time-released tablets, soft-gel capsules, and gummy. Although contradictory data exist, available evidence indicates that supplementation with multiple micronutrients with immune-supporting roles may modulate immune function and reduce the risk of infection.7

Nutrients That Are Essential for Immune Health

Essential dietary components such as vitamins C, D, and E, zinc, selenium, and the omega 3 fatty acids have well-established immunomodulatory effects and/or antioxidant properties, with possible benefits in the reduction and prevention of some infectious diseases.1,2,7,38-40 The most robust clinical data support the roles of vitamins C and D and zinc in immunocompetence; the roles of vitamins C and D in immunity are also particularly well elucidated in the published literature.11,40

Other studies indicate that several vitamins (i.e., A, B6, B12, C, D, E, and folate) and trace elements (i.e., zinc, iron, selenium, magnesium, and copper) have vital and complementary roles that support the innate and adaptive immune systems; thus, deficiencies or suboptimal status of these micronutrients may result in immune dysfunction and augmented susceptibility to pathological infection.1,2,7,11,38-40 Studies have also revealed that omega-3 fatty acids also support an effective immune system, explicitly via assisting in resolving the inflammatory response.1,41

These nutrients are vital for every stage of immune response and the role of nutrition in supporting the immune system has been confirmed in numerous studies. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that even a slight deficit in 1 or more of these micronutrients can impair the immune system’s function.7 While there are numerous dietary supplements marketed for immune support, this program will focus on some of the most commonly used supplements.

Vitamin C

Vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) is classified as a water-soluble nutrient that is naturally present in some foods, added to some foods, and available as a dietary supplement. The human body is unable to endogenously synthesize this vitamin due to loss of a key enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway; therefore, it is considered an essential component of a healthy diet.2 Extensive research has established that vitamin C is a vital nutrient in overall immune health and is the most well-known immune-boosting supplement. Vitamin C deficiency can impair the immune system and increase the risk of infection.2,42 Some studies have indicated that supplementation with vitamin C may reduce and/or prevent respiratory and systemic infections.2

Vitamin C acts as a potent antioxidant and contributes to the function of the immune system by supporting various cellular functions of the innate and adaptive immune system. In the innate immune system, vitamin C supports the epithelial barrier via synthesis of collagen and protection from reactive oxygen species (ROS).1,2 Vitamin C promotes the development and function of leukocytes, enhances chemotaxis, and dissipates leftover debris from neutrophil attacks.1,2 Throughout the innate system, vitamin C guards cells by combating ROS created by immune cells and renews oxidized glutathione and vitamin E.1,2 In adaptive immunity, vitamin C plays a role in B- and T-lymphocyte differentiation and proliferation, probably via gene regulation, and augments circulating immune system defenses, including antibodies and complement proteins.1,2

Studies. While the majority of studies indicate that taking vitamin C does not thwart the incidence of colds in the general population, its use may help diminish the duration and severity of symptoms.42 Findings from a 2018 meta-analysis of 9 randomized controlled studies (RCTs) revealed that supplementation with extra doses of vitamin C may diminish the duration of the common cold by up to half a day and reduce the severity of symptoms such as fever and chills.42 The authors recommended a small daily dose of vitamin C (no more than 1.0 g/day) to boost immunity and a larger dose of vitamin C during the duration of the common cold (usually 3.0-4.0 g/day) to improve recovery.42

Several RCTs and reviews have assessed the efficacy of vitamin C for treating or preventing the common cold. Examples include the following:

- A 2013 Cochrane review of results from 29 clinical trials that included more than 11,000 individuals discovered that taking vitamin C regularly (≥0.2 g/day) did not diminish the prevalence of colds in the general population but may be beneficial for individuals exposed to brief periods of severe physical exercise (e.g., marathon runners, skiers, and soldiers training in subarctic conditions).43,44 Moreover, some studies had demonstrated that vitamin C is correlated with modest decreases in the length and severity of cold symptoms; however, these results were not replicated in the few therapeutic trials that had been conducted.43

- A 2012 review exploring the treatment of the common cold in pediatric patients and adults found that prophylactic vitamin C moderately diminishes the duration of cold symptoms, but not the prevalence of colds in both patient populations.45

Administration. According to the Natural Medicines website, some experts suggest taking 200 mg/d of vitamin C to prevent respiratory tract infections (RTIs) or 1 to 2 g/day at the onset of symptoms to improve recovery (Table 2).46,47 Individuals who smoke need more vitamin C to offset the oxidative stress of smoking, and in general, smokers have lower concentrations of vitamin C in their blood.47 Health experts indicate that sufficient intake of vitamin C via diet and/or supplementation is critical to preserving immune function and resistance to infections.2,47 Vitamin C is generally considered safe; however, high doses can cause digestive disturbances such as diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal cramps.43 Adverse events (AEs) are more likely to occur at doses above the tolerable upper intake level of 2 g/day.46 Patients with diabetes, recurrent renal calculi, or renal disfunction should avoid prolonged use of high-dose vitamin C supplementation.37 According to the NIH, high intakes of vitamin C may augment urinary oxalate and uric acid excretion, which could contribute to the formation of renal calculi, especially in individuals with renal disorders.47

| Table 2. Recommended Dietary Allowance for Vitamin C47,a |

| Age |

Men |

Women |

Pregnancy |

Lactation |

| 0-6 months |

40 mgb |

40 mgb |

|

|

| 7-12 months |

50 mgb |

50 mgb |

|

|

| 1-3 years |

15 mg |

15 mg |

|

|

| 4-8 years |

25 mg |

25 mg |

|

|

| 9-13 years |

45 mg |

45 mg |

|

|

| 14-18 years |

75 mg |

65 mg |

80 mg |

115 mg |

| ≥19 years |

90 mg |

75 mg |

85 mg |

120 mg |

aSmokers: Individuals who smoke require 35 mg/day more vitamin C than nonsmokers.

bAdequate intake.

|

Vitamin D

Vitamin D, also known as the sunshine vitamin, is unique when compared with other vitamins because it can be made by the human body.18 Vitamin D is classified as a fat-soluble steroid hormone precursor. It is synthesized after ultraviolet B radiation exposure of 7-dehydrocholesterol in the epidermis of the skin, where it is converted into the circulating precursor cholecalciferol.1,7,18 In the liver, cholecalciferol is hydroxylated to form 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which is transformed into the active hormone 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) in the kidneys.1,7,18

Vitamin D receptors are found in almost all cells of the immune system and have multiple roles in immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and antiviral responses for several body systems, including in the innate and adaptive immune responses.18,39,48 Vitamin D can influence the innate immune system in numerous ways including via barrier function of epithelial cells in the eyes and intestinal tract, which augments chemotactic, phagocytic, and bactericidal activities of key innate immune cells including monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.1,18,39,49 In the adaptive immune system, vitamin D helps differentiate naive T cells into effector T cells, including T-killer or T-helper cells; studies have shown that insufficient levels of vitamin D can weaken this process.1,50

Studies. In general, studies show vitamin D supplementation has protective benefits against acute respiratory infections, particularly in those who are vitamin D deficient.40 Data gathered between 2005 and 2006 by the National Health and Nutrition and Examination Survey (NHANES) revealed that inadequate levels of vitamin D were found in 41.6% of 4495 participants. Researchers indicated that race was a significant risk factor with African-American adults having the highest prevalence rate of vitamin D deficiency (82.1%, 95% CI, 76.5%-86.5%) followed by Hispanic adults (62.9%; 95% CI, 53.2%-71.7%). Additional risk factors for vitamin D deficiency that were identified included obesity, lack of college education, and lack of daily milk consumption.40

Low vitamin D levels continue to be a health issue in developed and undeveloped countries. Epidemiologic studies have indicated that vitamin D deficiency is strongly linked with common chronic diseases such as bone metabolic disorders, tumors, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes, as well as the risk for neuropsychiatric and autoimmune diseases.51 Observational data in adults have revealed that low levels of vitamin D are linked with exacerbated RTI complications, and even augmented mortality from RTIs in adults aged 50 to 75 years.52 However, meta-analyses of prospective clinical trials in adults reveal that taking vitamin D supplements of 300 to 4,000 IU/day for 7 weeks to 5 years does not diminish the odds of developing an RTI or severe respiratory complications, such as emergency department utilization, hospitalization, and death, when compared with placebo.53 These results were comparable in subgroup analyses assessing overall vitamin D dose and baseline vitamin D status.53,54 In contrast, the largest single clinical trial, conducted in adults aged 60 years or older, revealed that taking vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) 60,000 IU once monthly for up to 5 years diminished the duration of total and severe respiratory symptoms by nearly 0.5 days, but did not reduce the prevalence of respiratory illness, when compared with placebo.55

Administration. According to the Natural Medicine website, recommendations for supplemental vitamin D doses vary considerably, and typically, patients should not exceed the tolerable upper limit of 4000 IU/day, unless advised by a HCP.56 The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Dietary Supplements suggests adults consume 600 to 800 IUs (15-20 mcg) of vitamin D daily (Table 3).57 Excessive doses of vitamin D can lead to toxicity with symptoms of hypercalcemia, which can cause nausea, vomiting, weakness, frequent urination, and sometimes azotemia and anemia.56

| Table 3. Recommended Dietary Allowances for Vitamin D57 |

| Age |

Men |

Women |

Pregnancy |

Lactation |

| 0-12 monthsa |

10 mcg

(400 IU) |

10 mcg

(400 IU) | | |

| 1-13 years |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

15 mcg

(600 IU) | | |

| 14-18 years |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

| 19-50 years |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

| 51-70 years |

15 mcg

(600 IU) |

15 mcg

(600 IU) | | |

| >70 years |

20 mcg

(800 IU) |

20 mcg

(800 IU) | | |

| aAdequate intake. |

Zinc

Zinc is an essential trace mineral with multiple roles in numerous biological processes, including normal growth and the development of reproductive organs. It is involved in the mobilization of vitamin A from the liver and in the enhancement of follicle stimulating and luteinizing hormones, spermatogenesis and normal testicular function.37 Zinc is also critical for several cellular immune functions for both the innate and adaptive immune systems, and vital for stabilization of membrane function.1,37,38,58 Zinc controls inflammatory activity and has antiviral and antioxidant functions.58 It supports immune cells and, similar to vitamin C, may diminish the severity and duration of the common cold.1,38,58 In the innate immune system, zinc helps maintain mucosal integrity.1,58 In the adaptive immune system, it is involved with T-cell development, differentiation, and T-cell and B-cell activation signaling; zinc also stimulates proliferation of T-helper and T-killer cells, which assist in the organization and assault on pathogens.1,58

Studies. It has been hypothesized that zinc supplementation inhibits viral replication and attachment to the nasopharyngeal mucous, and via this mechanism, zinc may be useful in the management of the common cold.38 Numerous RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have investigated the clinical effects of zinc on the common cold. A 2015 meta-analysis of 3 randomized trials exploring the use of zinc acetate lozenges for the common cold (dosages of 80-92 mg/day) discovered that zinc acetate lozenges reduced the duration of many common cold symptoms, such as nasal discharge, nasal congestion, sneezing, sore throat, cough, and muscle ache.59 However, no differences in duration of headaches and fever were observed. The authors concluded that zinc acetate lozenges (at doses of ≈80 mg/day) may be a beneficial treatment for the common cold, when initiated within 24 hours of symptom onset and used for less than 2 weeks.59

A 2013 review by Singh and Das found that oral zinc diminished the duration of colds in healthy individuals when taken within 24 hours of symptom onset, though caution should be used due to the heterogeneity of the data.60Also a noteworthy decrease in duration of the cold was observed with zinc doses of 75 mg/day or higher.60 Comparable results were found in a 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 RCTs with 2121 participants, though the authors also noted more research was warranted.61 Singh and Das also examined prophylactic use of oral zinc and found it reduced the incidence of colds, absences from school and work, and antibiotic prescriptions, though no firm recommendation could be made due to insufficient data.60

A 2012 review determined there is evidence supporting the use of oral zinc in pediatric patients to treat and prevent the common cold.62 One of the studies discussed was a large study of healthy pediatric patients, aged 2 to 10 years. They found that prophylactic use of zinc sulfate at a dose of 15 mg/day during respiratory illness season resulted in a noteworthy reduction in the number of colds and days absent from school.63However, the authors noted its use may be limited because of the need for frequent administration and the potential AEs, including dysgeusia, throat irritation, nausea, and diarrhea.63

Administration. Zinc is most effective when taken 1 hour before or 1 hour after a meal, but if GI upset occurs, administration with food may minimize it.37 According to the NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), the use of oral lozenges may diminish the duration of the common cold when initiated within 24 hours of symptoms and taken for less than 2 weeks.43 Health experts indicate that oral zinc supplementation is safe up to the upper limit of 40 mg/day in adults, but safety is less certain with greater doses that are necessary for common cold management (Table 4).37,58,64 Use of oral zinc has been associated with nausea and other GI symptoms (diarrhea and vomiting), which are typically dose related.43 Long-term use of zinc, especially in high doses, may cause copper deficiency and may increase the risk of urinary tract issues and reduce immune function.43 Use of intranasal zinc can cause anosmia, which may be long-lasting or permanent.43,64 Since most dietary zinc is obtained from animal products, vegetarians may need higher amounts of zinc because diets high in fiber phytates impede zinc absorption.37

| Table 4. Recommended Dietary Allowances for Zinc58 |

| Age |

Men |

Women |

Pregnancy |

Lactation |

| 0-6 months |

2 mga |

2 mga |

|

|

| 7-12 months |

3 mg |

3 mg |

|

|

| 1-3 years |

3 mg |

3 mg |

|

|

| 4-8 years |

5 mg |

5 mg |

|

|

| 9-13 years |

8 mg |

8 mg |

|

|

| 14-18 years |

11 mg |

9 mg |

12 mg |

13 mg |

| ≥19 years |

11 mg |

8 mg |

11 mg |

12 mg |

| aAdequate intake. |

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is a potent lipid-soluble antioxidant that guards the cell membranes against lipid peroxidation from free radical attack and has numerous roles in immune function.1 It also supports the epithelial barriers and data show that adequate levels of vitamin E expand the function of many innate immune cells, such as the cytotoxic activity of NK cells and neutrophil movement and phagocytosis.1,65

Studies. Vitamin E deficiency weakens the immune function in animal and human studies and this function can be restored with supplementation.1,18 A large RCT revealed that vitamin E is especially beneficial for enhancing the immune function of older patients. Researchers investigated the effects of 1 year of vitamin E supplementation on respiratory infections in 600 nursing home residents (aged ≥65 years).66 Residents were supplemented with 200 IU/day of vitamin E (dl-α-tocopherol) versus placebo; in those who received vitamin E supplementation, incidence of upper respiratory infection was reduced by 20%.66

Administration. Vitamin E is generally well tolerated. Patients should be advised that exceeding recommended amounts may increase risk of bleeding (Table 5).37,67

| Table 5. Recommended Dietary Allowances for Vitamin E67 |

| Age |

Men |

Women |

Pregnancy |

Lactation |

| 0-6 monthsa |

4 mg |

4 mg |

|

|

| 7-12 monthsa |

5 mg |

5 mg |

|

|

| 1-3 years |

6 mg |

6 mg |

|

|

| 4-8 years |

7 mg |

7 mg |

|

|

| 9-13 years |

11 mg |

11 mg |

|

|

| ≥14 years |

15 mg |

15 mg |

15 mg |

19 mg |

| aAdequate intake. |

Echinacea

Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea, Echinacea angustifolia, and Echinacea pallida) is commonly known as purple cornflower. There are 9 known species of this herb, all of which are native to North America.68,69 It is traditionally used to prevent or treat colds, influenza, and other infections and is thought to stimulate the immune system.68,69 The NCCIH indicates that Echinacea is thought to possess antioxidant and antibacterial activities, to stimulate monocytes and NK cells, and to inhibit viruses from binding to host cells.70

Studies. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2019 discovered that Echinacea might prevent upper RTIs, but it is unclear whether the effect is clinically meaningful. In addition, there was no evidence that Echinacea changed the duration of upper RTIs.70 A 2014 Cochrane review of 24 double-blind RCTs with 4631 participants concluded that Echinacea products have not been shown to provide benefits for treating colds.71 Although some preparations may be more effective than placebo for treating colds, the overall evidence for clinically relevant treatment effects is uncertain. Moreover, although the results of individual prophylaxis trials consistently demonstrated positive (though not significant) trends, those potential effects are of questionable clinical relevance.71 A 2013 review concluded that therapeutic use of Echinacea purpurea may improve cold symptoms in adults, but the evidence is inconsistent. The review also concluded that prophylactic use of Echinacea preparations is ineffective for thwarting the common cold.72The effects of Echinacea in pediatric patients are unclear; only a small amount of research has been done in pediatric patients, and the results of that research are inconsistent.72

Administration. In adults, Echinacea has been used in doses up to 16 g/day for 35 days, but doses vary extensively depending on the specific product.68 While generally well tolerated, the most common AEs include GI discomfort and headache.68,69 Serious AEs are possible, including flu-like syndrome and acute cholestatic hepatitis.68,69 Pharmacists should advise patients with severe systemic illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, multiple sclerosis, tuberculosis, and autoimmune disorders (including rheumatoid arthritis and those using immunosuppressants) to avoid the use of Echinacea because it may exacerbate these conditions.69,70 Individuals who are allergic to or have a hypersensitivity to ragweed, daisies, or chrysanthemums should avoid use of Echinacea due to the potential for cross-sensitivity.68,69

Elderberry

Elderberry is the dark purple berry of the European elder or black elder tree, also known as Sambucus nigra.43,69 Elderberry is promoted as a dietary supplement for colds, influenza, and other conditions.

Studies. According to the NCCIH, a small number of studies have assessed the clinical benefits associated with elderberry for influenza and other upper respiratory infections; however, conclusive evidence from high-quality clinical trials is deficient.43 A 2020 review concluded that although there is a theoretical benefit with elderberry for the treatment of viral infections, there is not enough conclusive evidence from high-quality clinical trials.73 Another meta-analysis of 4 studies from 2019 revealed that supplementation with black elderberry was significantly effective at diminishing the total duration and severity of upper respiratory symptoms, compared with placebo.74 In 2016, a double-blind RCT evaluated elderberry in air travelers and suggested that taking a dose of 300 mg twice a day may diminish cold symptom duration and severity.75 More recently, a systematic review of 5 RCTs in 2021 explored the use of various elderberry formulations and doses for the prevention and treatment of viral respiratory illnesses.76 The authors found that elderberry supplementation for 2 to 16 days might decrease the severity and duration of the common cold and the duration of influenza, but does not appear to diminish the risk of the common cold.76 However, the authors noted that the evidence is ambiguous because the studies were small and heterogeneous, thus more research is warranted.76

Administration. The Natural Medicines website indicates that the most frequently used doses for elderberry fruit extracts are up to 1200 mg/day for 2 weeks or up to 500 mg/day for up to 6 months.77 Moreover, an elderberry syrup has been used in a dose of 15 mL (1 tablespoon) 4 times daily for 5 days.77 Patients with autoimmune conditions should be advised to avoid the use of elderberry since it may exacerbate these conditions.77

Overview of Scientific Data That Supports Immune-Boosting Supplements for the Prevention and Management of COVID-19

Thus far, various publications have revealed that sales of dietary supplements and nutraceuticals soared during the pandemic due to their possible “immune-boosting” effects.78,79 Although little is known about the efficacy of some dietary supplements in reducing severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections,78-80 recent evidence has highlighted that nutritional supplementation could play a supportive role in improving clinical outcomes in some patients with COVID-19, particularly those with deficiencies in certain micronutrients.

According to the NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines, there is insufficient evidence to recommend either for or against the use of certain dietary supplements such as vitamin C, vitamin D, or zinc for the treatment of COVID-19. Health experts indicate that limited observational data suggest a possible correlation between certain vitamin and mineral deficiencies and more severe infection.73,79,81 One study explored the relationship between immunity and nutrition and their roles in COVID-19 infections.79 In the study, vitamin B1, B6, B12, and D, folate, selenium, and zinc levels were measured in 50 hospitalized patients with COVID-19. The researchers found that overall, 76% of the patients had vitamin D deficiency and 42% had selenium deficiency; however, no significant increase in the incidence of deficiency was found for vitamins B1, B6, and B12, folate, and zinc in patients with COVID-19.79 However, there are no high-quality data that suggest supplementation with vitamin C, vitamin D, or zinc diminishes the severity of COVID-19 in non-hospitalized patients.73,79,81,82

Published and ongoing research suggests that the administration of higher than recommended daily doses of nutrients such as vitamins C, D, and E, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids might have a beneficial effect, potentially reducing COVID-19 viral load and length of hospitalization.7,83-85 Research has demonstrated that deficiencies in nutrients such as vitamins C, D, and E and trace elements such as zinc and omega-3 fatty acids can result in immune dysfunction and increase susceptibility to pathological infection. Recent findings also indicate that dietary insufficiency of certain vitamins and minerals has been observed in high-risk groups of patients with COVID-19, such as the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities, therefore augmenting risks of serious COVID-19 infections with increased rates of hospitalization and mortality.38,86

Vitamin D and COVID-19

While some health experts disagree about whether vitamin D has a role in clinical outcomes for patients with COVID-19, vitamin D supplementation has gained significant popularity, especially at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic due to findings from numerous studies. These studies have suggested that lower levels of vitamin D are correlated with elevated rates of serious COVID-19 infections and mortality rates. 38,82,85-87A study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism found that 80% of over 200 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 had a vitamin D deficiency.86Other publications have indicated comparable findings that suggest low levels of vitamin D or deficiency are directly correlated with the incidence of severe infection and hospitalization.38,82,85-87

Vitamin C and COVID-19

In a meta-analysis of RCTs investigating the role of vitamin C supplementation in COVID-19, researchers indicated that treatment with vitamin C did not diminish rates of mortality and there was no indication of a significant clinical benefit associated with the use of this nutrient in the treatment of COVID-19.88 An observational study indicated that vitamin C status was very low in their cohort of patients with COVID-19–associated acute respiratory distress syndrome.89 Further studies are warranted to ascertain the actual prevalence of vitamin C deficiency in those with COVID-19 and if treatment with vitamin C has any impact on the disease.89

Zinc and COVID-19

Because the role of zinc in immune health has been well reviewed and zinc supplementation has been demonstrated to boost levels of NK cells, which are vital for host protection against viral infections, researchers hypothesize that this may also be true for COVID-19 symptoms; however, more research is warranted.79,80 A prospective study exploring fasting zinc levels in COVID-19 patients at the time of hospitalization revealed that a considerable number of patients with COVID-19 had zinc deficiency. Those individuals had more complications, and the degree of deficiency was directly correlated with longer hospital stays and elevated rates of mortality.80 However, to date there are no conclusive data regarding the role of zinc supplementation in COVID-19.

The Role of the Pharmacist

Because they are easily accessible and given their drug expertise, pharmacists are well poised to help patients select nutritional supplements that may boost immune health, as well as share clinical data about the role of these supplements in overall and immune health. Furthermore, interventions by pharmacists may increase awareness of the value of balanced nutrition and promote the safe use of supplements marketed for immune health. When counseling patients about supplements for immune health, it is critical to remind them that function of the immune system is impacted by many lifestyle factors including proper nutrition, hydration, routine exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, getting sufficient sleep, and managing stress. Patients should also be reminded that obtaining nutrients via a healthy and balanced diet is the optimal approach to immune health and overall well-being; supplements should never be a substitute for a nutritious and balanced diet.

Pharmacists are in a pivotal position to help patients select dietary supplements that meet their individual nutritional needs and to ascertain the appropriateness of use and screen for potential drug-supplement interactions and contraindications. They can also highlight the significance of safely using dietary supplements and counsel patients on the benefits versus risks of using dietary supplements, including herbal supplements. It is also essential for pharmacists to remind patients not to exceed the tolerable upper limits of these supplements and to report supplement use to their other HCPs.

They can also ensure patients clearly understand that dietary supplements are not intended to treat, cure, or alleviate the effects of diseases, nor can they completely prevent diseases. Pharmacists should also remind patients that some supplements may interfere or interact with diagnostic tests results and laboratory assays. According to the Handbook of Drug Nutrient Interactions, pharmacists can be instrumental in identifying drug-supplement interactions, some of which may be clinically significant, but frequently go unnoticed by patients and other HCPs. A drug-supplement interaction is considered significant if the interaction alters a pharmacotherapeutic response or affects a patient’s nutritional status.90

Pharmacists can also identify patients who may be at risk for deficiencies in nutrients that are essential for immune health due to certain medical conditions or the use of certain pharmacologic agents that may deplete or interact with specific nutrients. Examples of patient populations that may be at augmented risk for these types of interactions are in Table 6.37

| Table 6. Individuals at Expanded Risk of Drug-Supplement Interactions37,90,91 |

- Patients with chronic diseases and/or multiple comorbidities, especially those taking ≥1 medication

- Elderly and pediatric patient populations

- Patients with poor or compromised nutritional status

- Patients with poor overall health status

- Pregnant and lactating women

- Transplant patients

- Patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation.

- Patients on restricted diets (i.e., vegetarian, vegan, or keto diets)

|

It is important that pharmacists seize every possible opportunity to expand awareness about drug-supplement interactions because this understanding is key to patient safety, ensuring optimal therapeutic effects, and thwarting potential interactions. One study revealed that about 70% of patients who use prescription drugs do not inform their primary HCPs about their concurrent use of dietary supplements.91

There are many potential nutrient-drug interactions (Table 7).37,46,47,57-59,64,65,69,77,90-93 A helpful resource, available via a subscription, is the Natural Medicines website (https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com), where pharmacists can screen for potential interactions.

| Table 7. Examples of Drug Nutrient-Interactions37,46,47,57-59,64,65,69,77,90-93 |

| Supplement |

Examples of Potential Interactions and Contraindications |

| Vitamin C |

- May interact with chemotherapeutic agents such as cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, and doxorubicin and radiation

- When used in combination with other antioxidants, may diminish the increase in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels from combination niacin-simvastatin. HCPs should monitor lipid levels in individuals taking both statins and antioxidant supplements

- Proton pump inhibitors may cause deficiencies in vitamin

- Both ASA and NSAIDs may lower levels of vitamin C

|

| Vitamin D |

- Corticosteroids can diminish calcium absorption and impair vitamin D metabolism

- Orlistat can diminish the absorption of vitamin D and other fat-soluble vitamins

- Statins may decrease cholesterol synthesis and therefore reduce synthesis of vitamin D

- Both phenobarbital and phenytoin increase the hepatic metabolism of vitamin D to inactive compounds and reduce calcium absorption

- The combination of thiazide diuretics with vitamin D supplements (which increase intestinal calcium absorption) might lead to hypercalcemia, particularly among older adults and individuals with compromised renal function or hyperparathyroidism

|

| Vitamin E |

- Vitamin E can impede platelet aggregation and antagonize vitamin K-dependent clotting factors. As a result, taking large doses with anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications can raise the risk of bleeding, particularly in conjunction with low vitamin K intake

- Some individuals take vitamin E supplements with other antioxidants, such as vitamin C, selenium, and beta-carotene. This collection of antioxidant ingredients diminished the increase in HDL cholesterol levels, especially levels of HDL2 among individuals treated with a combination of simvastatin and niacin

|

| Zinc |

- May interact with quinolone and tetracycline antibiotics. Taking the antibiotic ≥2 hours before or 4-6 hours after taking a zinc supplement minimizes this interaction

- Thiazide diuretics increase urinary zinc excretion by as much as 60%. Prolonged usage of thiazide diuretics could deplete zinc tissue levels, so clinicians should monitor zinc status in patients taking these medications

- ACE inhibitors may decrease levels of zinc

- Zinc may reduce the absorption of and effectiveness of the NSAIDs

|

| Echinacea |

- Echinacea can raise plasma levels of caffeine by inhibiting its metabolism

- Possible interaction with immunomodulating therapies

- Caution with use of CYP3A4 substrates that have low oral bioavailability such as verapamil, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus

- Advise patients with autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, pemphigus vulgaris, or others to avoid or use Echinacea with caution

|

| Elderberry |

- Elderberry may interfere with immunosuppressant therapy by decreasing the effectiveness of immunosuppressant agents due to its immunostimulant activity

- Possible additive effects with antihypertensive and antihyperglycemic agents; increased monitoring recommended

|

| ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme; ASA=acetylsalicylic acid; HCP=health care provider; HDL=high-density lipoprotein; NSAID=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. |

To decrease or avoid drug-supplement interactions and/or contraindications, pharmacists can encourage patients to maintain a comprehensive list of all their medications, including supplements. Patients should also be counseled on the proper use of selected supplement(s) and reminded to adhere to manufacturer instructions and only take the recommended dosages. Patients taking other medications and those with chronic medical conditions should always consult their primary HCPs before taking any supplements. When helping patients who are looking for guidance on immune health supplements, pharmacists should also remind them about the importance of maintaining routine health care and staying up to date with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommendations for immunizations based on the patient’s age range and/or medical history.

It is particularly important that pharmacists screen for therapeutic duplications when patients are taking multiple supplements to avoid toxicity due to taking more than the recommended upper limit of a nutrient—especially with the lipid-soluble vitamins. Additionally, because dietary supplements are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in a method different from that used for other nonprescription drugs, patients may express concerns about the efficacy and safety of dietary supplements. Thus, pharmacists should remind patients to always select dietary supplements from reputable manufacturers such as supplements with the US Pharmacopeia (USP) verification seal of approval. This verification ensures that these products have been independently certified for quality and:

- Contain the ingredients listed on the label, in the declared potency and amounts;

- Do not contain harmful levels of specified contaminants;

- Will break down and release into the body within a specified amount of time; and

- Have been manufactured according to FDA current Good Manufacturing Practices, using sanitary and well-controlled procedures.94

FDA and Safe Use of Dietary Supplements

The FDA has established recommendations for consumers regarding the safe use of dietary supplements (Box).95,96 Excellent patient education resources regarding dietary supplements also can be found on the FDA website https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/fda-101-dietary-supplements.

| Box. FDA Recommendations Regarding Dietary Supplements and Key Counseling Tips to Relay to Patients95,96 |

- Before initiating a dietary supplement, consult your primary HCP, especially if pregnant, breastfeeding, or have a chronic medical condition such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease and/or are taking any other medications to avoid possible drug-nutrient interactions and/or contraindications

- Inform primary HCP and pharmacist about all vitamins, minerals, herbals, or alternative supplements you are taking, especially before having an elective surgery, to avoid potential interactions or complications and maintain an updated list of dietary supplements

- Always buy supplements from reputable companies, especially those with the USP verification seal

- Always adhere to the manufacturer recommended dosages and instructions, and contact your primary HCP if you have any concerns or questions

- Most surgery-related AEs can be avoided by discontinuing dietary supplement products ≥1-2 weeks before surgery and during the postoperative period while prescription medications such as anticoagulants or antibiotics are being used

- When in doubt, always ask your pharmacist or primary HCP

- Never self-treat if you suspect you have a nutritional deficiency; seek care from your primary HCP

|

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Position Statement on the Use of Dietary Supplements

According to a position statement from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), the extensive, undiscerning usage of dietary supplements may pose noteworthy risks to consumers if not taken correctly; therefore, HCPs including pharmacists have a professional responsibility to augment awareness about the potential risks and to tailor clinical interventions when necessary to patient need.97 Moreover, the ASHP encourages pharmacists and other HCPs to integrate patient education initiatives regarding the proper use of dietary supplements into clinical practice when interacting with patients and encourages pharmacists to increase efforts to monitor and prevent interactions between dietary supplements and drugs.97 The ASHP also notes that in order for pharmacists to efficiently counsel patients who are seeking guidance about dietary supplements, they should be cognizant of the:

- Recommended uses of frequently used dietary supplements and the published clinical data validating their efficacy and safety;

- Established and possible interactions between frequently used dietary supplements and prescription and nonprescription medications;

- Recommended approaches for therapeutic monitoring for frequently used dietary supplements, including signs and symptoms of potential AEs and toxicities;

- Proven and potential effects of certain medical conditions on supplement absorption, distribution, and elimination; and

- Safety of using dietary supplements before or after surgery and suggested guidelines and parameters for before and after surgery.97

Summary

An extensive body of clinical data clearly demonstrates that inadequacies/deficiencies in the intake of various micronutrients can impair/weaken the immune system. Moreover, research has also illustrated that, in conjunction with healthy eating habits and other lifestyle measures such as routine exercise and adequate sleep, the use of dietary supplements can be beneficial in maintaining and/or boosting the immune system. The prevalence of immune deficiencies among all age groups in the United States evidently highlights the need for pharmacists to expand awareness of the clinical benefits associated with immune-boosting dietary supplements, as well as the value of implementing patient education measures that can guide patients in the proper selection of immune-boosting dietary supplements. Pharmacists are also well poised to identify patients at risk for nutritional deficiencies based on their use of certain medications and/or medical conditions. With their drug expertise, pharmacists are equipped with relevant knowledge that will enable them to make clinical recommendations tailored to patient’s nutritional needs.

References

- Reider CA, Chung RY, Devarshi PP, et al. Inadequacy of immune health nutrients: intakes in US adults, the 2005-2016 NHANES. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1735. doi:10.3390/nu12061735

- Carr AC, Maggini S. Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients. 2017;9:1211. doi:10.3390/nu9111211

- Calder PC. Feeding the immune system. Proc Nutr Soc. 2013;72(3):299-309. doi:10.1017/S0029665113001286

- Delves PJ. Overview of the immune system. Merck Manual for Healthcare Professionals Online Edition. Reviewed September 2021. Accessed March 5, 2022. http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/immunology-allergic-disorders/biology-of-the-immune-system/overview-of-the-immune-system

- org. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. How does the immune system work? Updated April 23, 2020. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279364/

- Gombart AF, Pierre A, Maggini S. A review of micronutrients and the immune system–working in harmony to reduce the risk of infection. Nutrients. 2020;12:236. doi:10.3390/nu12010236

- Maggini S, Pierre A, Calder PC. Immune function and micronutrient requirements change over the life course. 2018;10(10):1531. doi:10.3390/nu10101531

- Nicholson LB. The immune system. Essays Biochem. 2016;60(3):275-301. doi:10.1042/EBC20160017

- Julier Z, Park AJ, Briquez PS, Martino MM. Promoting tissue regeneration by modulating the immune system. Acta Biomater. 2017;53:13-28. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.056

- Mitra S, Paul S, Roy S, et al. Exploring the immune-boosting functions of vitamins and minerals as nutritional food bioactive compounds: a comprehensive review. Molecules. 2022;27(2):555. doi:10.3390/molecules27020555

- Bohnenkamp S. Immuno-oncology: another option for treatment of cancer. MedSurg Nursing. 2018. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Immuno-Oncology%3A+Another+Option+for+Treatment+of+Cancer-a0559210967

- Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(10):1014-1022. doi:10.1038/ni.2703

- Aristizábal B, González Á. Innate immune system. In: Anaya JM, Shoenfeld Y, Rojas-Villarraga A, et al, eds. Autoimmunity: From Bench to Bedside [Internet]. Bogota (Colombia): El Rosario University Press; 2013. Chapter 2. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459455/

- Chaplin DD. Overview of the immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 suppl 2):S3-S23. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.980

- Hillion S, Arleevskaya MI, Blanco P, et al. The innate part of the adaptive immune system. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;58:151-154. doi:10.1007/s12016-019-08740-1

- Wu D, Lewis ED, Pae M, Meydani SN. Nutritional modulation of immune function: analysis of evidence, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Front Immunol. 2019;9:3160. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.03160

- Wiseman AC. Immunosuppressive medications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(suppl 2):332-343. doi:10.2215/CJN.08570814

- American Psychological Association. Stress effects on the body. Published November 1, 2018. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(4):601-630. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601

- Ikonte CJ, Mun JG, Reider CA, Grant RW, et al. Micronutrient inadequacy in short sleep: analysis of the NHANES 2005–2016. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2335. doi:10.3390/nu11102335

- Suni E. How sleep affects immunity. Sleep Foundation. Updated March 11, 2022. Accessed on March 5, 2022. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/physical-health/how-sleep-affects-immunity

- Finger CE, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Gutierrez A, et al. Age-related immune alterations and cerebrovascular inflammation. Mol Psychiatry. 2021. doi:10.1038/s41380-021-01361-1

- Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, et al. Immunosenescence and Its Hallmarks: How to Oppose Aging Strategically? A Review of Potential Options for Therapeutic Intervention. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2247. Published 2019 Sep 25. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02247

- Kim JH, Park K, Lee SB, et al. Relationship between natural killer cell activity and glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes and prediabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(5):1223-1228. doi:10.1111/jdi.13002

- Review study published in nutrients shows American adults lack critical nutrients to maintain a healthy immune system [press release]. Pharmavite Inc. June 25, 2020. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://www.pharmavite.com/perspectives/news/review-study-published-in-nutrients-shows-american-adults-lack-critical-nutrients-to-maintain-a-healthy-immune-system/#_edn1

- Bridgeman M, Rollins C. Essential and conditionally essential nutrients. In: Krinsky D, Berardi R, Ferreri S, et al, eds. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs: An Interactive Approach to Self-Care. 20th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2020. doi:10.21019/9781582123172

- Calder PC, Carr AC, Gombart AF, Eggersdorfer M. Optimal nutritional status for a well-functioning immune system is an important factor to protect against viral infections. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1181. doi:10.3390/nu12041181

- Forrest KY, Stuhldreher WL. Prevalence and correlates of vitamin D deficiency in US adults. Nutr Res. 2011;31(1):48-54. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2010.12.001

- Ran L, Zhao W, Wang J, et al. Extra dose of vitamin C based on a daily supplementation shortens the common cold: a meta-analysis of 9 randomized controlled trials. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1837634. doi:10.1155/2018/1837634

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. The common cold and complementary health approaches: what the science says. NCCIH Clinical Digest for Health Professionals. December 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/the-common-cold-and-complementary-health-approaches-science#vitamin-c

- Hemilä H, Chalker E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(1):CD000980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub4

- Fashner J, Ericson K, Werner S. Treatment of the common cold in children and adults. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(2):153-159.

- Vitamin C. Natural Medicines. Updated January 21, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=1001#background

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Vitamin C: fact sheet for health professionals. Updated March 26, 2021. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/

- Mrityunjaya M, Pavithra V, Neelam R, et al. Immune-boosting, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory food supplements targeting pathogenesis of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:570122. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.570122

- Kongsbak M, Levring TB, Geisler C, von Essen MR. The vitamin D receptor and T cell function. FrontImmunol. 2013;4:148. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2013.00148

- von Essen MR, Kongsbak M, Schjerling P, et al. Vitamin D controls T cell antigen receptor signaling and activation of human T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:344-349. doi:10.1038/ni.1851

- Wang H, Chen W, Li D, et al. Vitamin D and chronic diseases. Aging Dis. 2017;8(3):346-353. doi:10.14336/AD.2016.1021

- Brenner H, Holleczek B, Schöttker B. Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency and mortality from respiratory diseases in a cohort of older adults: potential for limiting the death toll during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrient 2020;12(8):2488. doi:10.3390/nu12082488

- Charan J, Goyal JP, Saxena D, Yadav P. Vitamin D for prevention of respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012;3(4):300-303. doi:10.4103/0976-500X.103685

- Jolliffe DA, Camargo CA Jr, Sluyter JD, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregate data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(5):276-292. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00051-6

- Pham H, Waterhouse M, Baxter C, et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on acute respiratory tract infection in older Australian adults: an analysis of data from the D-Health Trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(2):69-81. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30380-6

- Vitamin D. Natural Medicine. Updated January 27, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=929#dosing

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Vitamin D: fact sheet for consumers. Updated August 17, 2021. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Zinc: fact sheet for health professionals. Updated December 7, 2021. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Zinc-HealthProfessional/

- Hemilä H, Chalker E. The effectiveness of high dose zinc acetate lozenges on various common cold symptoms: a meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:24. doi:10.1186/s12875-015-0237-6

- Singh M, Das RR. Zinc for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD001364. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001364.pub4

- Science M, Johnstone J, Roth DE, et al. Zinc for the treatment of the common cold: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2012;184(10):E551-E561. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111990

- Robohm C, Ruff C. Diagnosis and treatment of the common cold in pediatric patients. 2012;25(12):43-47. doi:10.1097/01720610-201212000-00009

- Kurugöl A, Akilli M, Bayram N, Koturoglu G. The prophylactic and therapeutic effectiveness of zinc sulphate on common cold in children. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(10):1175-1181. doi:10.1080/08035250600603024

- Natural Medicines. Updated January 24, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=982#adverseEvents

- Lee GY, Han SN. The role of vitamin E in immunity. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):1614. doi:10.3390/nu10111614.

- Meydani SN, Leka LS, Fine BC, et al. Vitamin E and respiratory tract infections in elderly nursing home residents: a randomized controlled trial [published correction appears in 2004;292(11):1305] [published correction appears in JAMA. 2007;297(17):1882]. JAMA. 2004;292(7):828-836. doi:10.1001/jama.292.7.828

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Vitamin E: fact sheet for health professionals. Updated March 26, 2021. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminE-HealthProfessional

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Echinacea. Updated July 2020. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/echinacea

- McQueen C, Orr K. Natural products. In: Krinsky D, Berardi R, Ferreri S, et al, eds. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs: An Interactive Approach to Self-Care. 20th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2020. doi:10.21019/9781582123172

- David S, Cunningham R. Echinacea for the prevention and treatment of upper respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019;44:18-26. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2019.03.011

- Karsch-Völk M, Barrett B, Kiefer D, et al. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;20(2):CD000530. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub3

- Linde K, Barrett B, Wölkart K, et al. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD000530. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub2

- Adams KK, Baker WL, Sobieraj DM. Myth busters: dietary supplements and COVID-19. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54(8):820-826. doi:10.1177/1060028020928052

- Hawkins J, Baker C, Cherry L, Dunne E. Black elderberry (Sambucus nigra) supplementation effectively treats upper respiratory symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 2019;42:361-365. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2018.12.004

- Tiralongo E, Wee SS, Lea RA. Elderberry supplementation reduces cold duration and symptoms in air-travelers: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients. 2016;8(4):182. doi:10.3390/nu8040182

- Wieland LS, Piechotta V, Feinberg T, et al. Elderberry for prevention and treatment of viral respiratory illnesses: a systematic review. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21:112. doi:10.1186/s12906-021-03283-5

- Natural Medicines. Updated November 23, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=434

- Lordan R, Rando HM, COVID-19 Review Consortium, Greene CS. Dietary supplements and nutraceuticals under investigation for COVID-19 prevention and treatment. mSystems. 2021;6(3):e00122-21. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00122-21

- Im JH, Je YS, Baek J, et al. Nutritional status of patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.018

- Hernández JL, Nan D, Fernandez-Ayala M, et al. Vitamin D status in hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(3):e1343-e1353. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa733

- Donaldson M, Touger-Decker R. Dietary supplement interactions with medications used commonly in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(7):787-794. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0188

- Vitamin E. Natural Medicines. Updated November 29, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=954

- Natural Medicines. Updated November 5, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=981

- USP verified mark. United States Pharmacopeia. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://www.usp.org/verification-services/verified-mark

- Tips for dietary supplement users. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated February 23, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/information-consumers-using-dietary-supplements/tips-dietary-supplement-users

Back to Top