Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Module 8. Healthy Eating with Diabetes

|

IMPORTANT DEFINITIONS

Macronutrient: A type of food required in large amounts in the human diet.

Triglycerides: One of the main constituents of body fat (cholesterol) in humans. They store fat your body may need later for energy, but if they are too high, they put patients at risk for heart disease, liver problems, and many other health concerns.

Isoenergetic: Having the same or constant amount of energy.

|

INTRODUCTION

Nutrition is one of the most controversial health topics, with opinions about what constitutes a healthy diet ranging from one extreme (such as low carbohydrate) to the other (e.g., low fat). Diet is a major consideration in managing diabetes, and while carbohydrates have garnered the most interest related to glycemic control, other dietary components are likely equally important.

Given the controversies related to nutrition, even some of the most reputable organizations, like the American Diabetes Association (ADA), have chosen to refrain from giving specific dietary guidelines to people with diabetes, stating in their Standards of Care that “Studies examining the ideal amount of carbohydrate intake for people with diabetes are inconclusive.” However, they do acknowledge that “monitoring carbohydrate intake and considering the available insulin” can improve postprandial (after-meal) blood glucose control.1

Many people with type 2 diabetes are counseled to lose weight to help manage or potentially reverse diabetes or prediabetes. Weight loss may be a useful goal for people with type 2 diabetes who are overweight, but even preventing excessive weight gain in those with type 1 diabetes can help keep insulin action high and insulin needs lower, because staying in good physical shape helps insulin work more efficiently to control blood sugars.2 Sustaining a weight loss of as little as five to seven percent of total body weight can lead to a decrease in insulin resistance and improvements in blood glucose control and, therefore, allows for a reduction in the amount of medication taken.3 While the nutrition focus in this module is on the benefits of balancing carbohydrates, fats, and protein in the diet to control blood glucose levels, improvements in body weight will likely also result from a healthier diet and other lifestyle improvements.

What Constitutes a Healthy Diet for People with Diabetes?

Carbohydrate, fat, and protein are the dietary macronutrients that provide energy for activity and routine body functioning, although each of these nutrients has a different primary role. Protein helps to build muscle and other bodily structures, while fat is important as a source of stored energy and contributes to the health of the brain, nerves, hair, skin and nails. Carbohydrate is a major fuel source for the body, especially during physical activity, and is the primary supplier of energy for brain, nerves and muscles.

It helps to check blood glucose levels before and after meals to learn how foods affect them, particularly those containing a lot of carbohydrate (such as potatoes, bread, rice, and pasta). Keeping portion sizes in check if weight loss is a goal and managing blood glucose levels by providing a good balance of carbohydrate, fat, and protein will benefit people with diabetes.

|

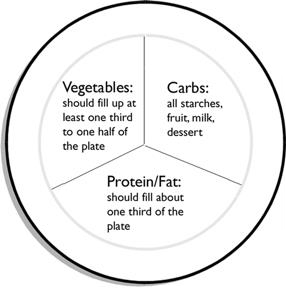

Does Your Plate Look Like This?

The Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston, world-renowned for its management and treatment of diabetes, suggests that daily food intake for people with diabetes should resemble this “plate” more than the MyPlate guidelines from the USDA (which recommend that half of the plate be com-promised of fruits and vegetables).

- Is your plate covered with colorful vegetables: dark green, orange, yellow and red?

- Is the fat trimmed off your meat and skin taken off?

- Did you choose leaner cuts of meat, poultry or fish?

- Did you choose whole grain pasta or breads? Brown rice or potato with skin?

- How much fat was used in cooking or added to your plate?

- Did you boil, steam, grill or bake instead of frying your foods?

Adapted from Joslin Diabetes Center education materials. Copyright © 2012 by Joslin Diabetes Center (www.joslin.org). All rights reserved.

|

Carbohydrate Intake

Carbohydrates have the greatest impact on the amount of glucose in the blood because they are turned into glucose relatively quickly. Many people with diabetes try to avoid or limit their in-take of carbohydrates as a way to keep blood glucose levels in check, but the human body needs fiber that is found in plant foods. Carbohydrates are also the body’s first choice of fuel during many physical activities, and not having enough in the diet may limit a person’s ability to exercise optimally.

Many people with diabetes count the grams of carbohydrate present in the foods they eat to help control their blood glucose levels, and others choose carbohydrates based on their glycemic index (how rapidly the food item raises blood glucose levels; see a later section addressing this topic for more details).4 The exact amount of carbohydrates a person with diabetes should consume varies based on physical activity levels, medications used, and overall insulin action. Starches and sugars ideally should be limited, but not fiber and non-starchy vegetables, such as salad greens, peppers, tomatoes, green beans, carrots, cauliflower, and onions.

Fiber Intake: Fiber includes all indigestible polysaccharides (a type of complex carbohydrate), including the natural ones in foods and others that are extracted or isolated from foods or made synthetically (e.g., Metamucil).5 Soluble fiber—found in oatmeal, legumes, seeds, fruits (such as apples, bananas, citrus fruits), and vegetables—dissolves in water, is partially metabolized in the large intestine by health-promoting bacteria, and helps lower blood cholesterol. Oats in particular may have a strong anti-inflammatory effect by increasing these healthful bacteria in the intestinal tract.6 An insoluble form of fiber is found in carrots, celery, and the skins of corn kernels; fruit peels, cores, and seeds; brown rice; and whole grains. Acting as roughage, most fiber passes through the human digestive system without being fully digested and ensures regular bowel movements. Since it resists acids and digestive enzymes in the stomach, fiber cannot be fully digested and, does not add calories to the diet.

In addition to the aforementioned ones, dietary fiber has many other health and metabolic benefits.5 For instance, a high-fiber diet may help reduce the chances of developing heart disease, diabetes, obesity, strokes, colorectal and other types of cancer, diverticulosis, and hemorrhoids.5 Fiber adds bulk and aids in portion control because it generally slows down the rate at which food empties from the stomach, makes people feel full longer, and prevents excessive eating and weight gain. From a diabetes and overall health standpoint, dietary fiber may reduce blood glucose and cholesterol, all while slowing the digestion of complex carbohydrates to glucose, thereby keeping blood glucose levels more stable.

Current research is focusing on the role of the gut microbiome—the bacteria that reside in the intestinal tract—on human health and disease. The human body hosts 100 trillion mostly benign (unharmful) bacteria, which help digest food, program the immune system, prevent infection, and even influence mood and behavior. The bacteria living on and in us make up an ecosystem that likely plays a role in many conditions that genes and environmental factors alone fail to explain, including obesity, autism, depression, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, and even cancer.7

In fact, it is very possible that the type of bacteria people have in their gut has a huge impact on whether they gain weight or stay slim, get diabetes or avoid it, and develop other chronic diseases or stay healthier.8 Although this research is ongoing, it is clear that fiber enhances the gut’s abundance of the good bacteria that reduce inflammation. For no other reason, patients with diabetes (and other metabolic health conditions) should eat as much fiber as possible to keep their health-promoting gut bacteria thriving and abundant.

|

Eat More Dietary Fiber

Although the low-carbohydrate craze has resulted in many products with added fiber (including pasta and tortilla shells), in general the more refined a product is, the less fiber it has. To find out the fiber content of any food, either read its nutrition label (if it comes in a box or package) or look up information online (https://fnic.nal.usda.gov/food-composition/macronutrients/fiber). A reasonable fiber goal is a minimum of 12.5 grams per 1,000 calories daily.

|

A good target is at least 20 to 35 grams of dietary fiber per day. Fiber is found only in plant-based foods, such as oats, oat bran, ground flaxseed, beans and fruits, wheat bran, apple peels, and most vegetables. Instead of trying to eat a certain amount, it may be easier to simply eat more nutritious plants, such as whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts and seeds.

Fat Intake

Diabetes can result in unhealthy changes in blood fats. Elevated levels of triglycerides (which ironically can result from eating highly refined carbohydrates) and unhealthier types of cholesterol play a major role in stimulating the inflammatory process leading to the development of cardiovascular disease.9 Not every type of fat is bad—although the healthiness of various fats is still being hotly debated in the nutrition world—but there is no doubt that a high intake of certain types of fat can contribute to the development of insulin resistance and negative changes in blood fats as much as intake of refined carbohydrates.10

Eat Fewer Trans and Processed Fats: Trans fats are created by manufacturers when they hydrogenate or partially hydrogenate liquid oils to alter their texture. Consumption of trans fats found in hydrogenated oils contributes to insulin resistance and makes it harder to keep blood glucose and cholesterol levels under control. Trans fats are found most abundantly in processed foods, crackers, cookies, baked goods, and more. The minimal amount of trans fats that we all get from natural sources (like cheese), however, are not considered as unhealthy for us as the manufactured ones.11

Highly processed meats (like bacon, sausage, and lunch meats) are also likely unhealthy due to the preservatives added. For example, eating even one fast food meal high in manufactured trans fats and highly processed fats can interrupt the normal flow of blood through arteries and veins for hours afterward, and make the body’s response to insulin sluggish as well. Conversely, eating a high-fat breakfast that contains mostly a good fat (like olive oil) instead of sausage allows blood glucose and insulin levels to stay lower.12 A high intake of highly processed meat has been associated with a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes.13,14

Soon we all are going to have to watch out for interesterified fat, which is also manufactured and added to processed foods in place of trans fats. Studies show that this new type of altered fat is also heart-unhealthy, probably as much so as trans fats, but it’s hard to know how much is in foods since its content does not have to be reported or listed on food labels.15,16

Eat More Omega and Healthy Plant Fats: Two dietary polyunsaturated fats are essential: omega-3 and omega-6. Both are important to include in a healthy diet, particularly for people with diabetes whose nutrition is even more important to preserve their long-term health.

Omega-3 fats are abundant in dark green, leafy vegetables (e.g., dark-colored lettuce, spinach, kale, turnip greens, etc.), canola oil, flaxseed oil, soy, some nuts (e.g. walnuts), fish, and fish oils. Only fish and fish oils contain larger amounts of two omega-3 fats called DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) and EPA (ecosapentanoic acid), which are critical for brain and nerve function, cardiovascular health, and more. Plant foods like walnuts contain mainly the essential omega-3 fat called ALA (alpha-linolenic acid), which can be converted into the other two by the body if in-take is low.

Omega-6 fats are abundant in the corn, sunflower, peanut, and soy oils used to make food products like margarine, salad dressing, and cooking oils, and they may actually help lower inflammation.17 A high vegetable fat intake may decrease type 2 diabetes risk in females.18

Diets high in certain types of fat—like the plant-based ones found naturally in avocados—may actually improve insulin action. Even tropical oils like coconut that are minimally processed are now considered healthier options despite the fact that most of their fats are saturated. Unnaturally low-fat diets can cause the liver to produce more bad cholesterol, especially if people replace fat with refined carbohydrates.10

The best advice is simply to cut down on the intake of unhealthier fats by eating more foods in their natural state, such as high-fiber vegetables, legumes, and fish. If people eat a diet that is moderate in fat (30 percent of daily calories) and avoid lower fat versions of snack foods that have added sugars and more refined carbohydrates in them, their blood cholesterol levels are more likely to go down.10

Healthiness of Fat in Red Meat, Dairy, Eggs, and Nuts: What about eating red meat, dairy products, and nuts and seeds? Although unprocessed red meats are unlikely to cause heart disease,13 healthier choices are available, including fish, nuts, legumes, fruits, and vegetables. If people consume cheese and milk, they should be advised to pick lower fat varieties, not because dairy fat is bad for health, but rather to lower their calorie intake.19 Also, diets rich in monounsaturated fats in olive oil, canola oil, and nuts and seeds are heart healthy and do not necessarily promote weight gain. If someone is following a weight loss diet and eats a handful of almonds or other nuts daily, he or she is likely to lose more weight than if eating the same number of calories without the nuts.20

Blood cholesterol should decrease as people eliminate trans and other processed fats from their diet. Everyone needs a certain amount of cholesterol, which is a waxy, fat-like substance important in cell and hormone composition, and the liver will simply make it as needed. Cholesterol is found in all animal products, including meat, poultry, shellfish, fish, eggs, and dairy, but not at all in plants. The cholesterol found in eggs is no longer as maligned as it once was, and it’s unlikely that the cholesterol in egg yolks is going to raise blood cholesterol levels.

Protein Intake

Protein has a minimal immediate effect on blood glucose levels, and it aids in the sensation of fullness. In fact, low-protein meal plans are associated with increased hunger. Eating more lean protein together with healthy fats may reduce appetite and help people achieve and maintain a lower calorie intake. Adequate intake of protein also helps to maintain lean body mass if they lose weight on a diet or gain more muscle mass from exercising, and eating enough protein is important for aging well.

Most foods with a significant amount of protein have a lower glycemic effect as protein is metabolized more slowly than carbohydrates, usually within three to four hours. In patients with type 2 diabetes, a greater protein intake does not increase plasma glucose, but increases the insulin response and leads to lower A1C levels.21 In fact, consuming as much as 30 to 40 percent of calories as protein, with a lower intake of carbohydrates and fats, may assist with diabetes control, weight loss, and weight maintenance. However, a high intake of protein from processed meats actually increases diabetes risk.14 Advise patients to choose high-quality sources of protein, such as lean meats and poultry, soy products, legumes, and fish. Moreover, a diet rich in soy protein appears to have a lasting beneficial effect for people with type 2 diabetes as it lowers fasting blood glucose levels, blood fats, C-reactive protein (an indicator of inflammation), and markers of kidney disease.

Carbohydrate Counting vs. Calorie Counting

Estimating how much insulin is needed to cover meals and snacks is frequently difficult. Many people with diabetes have been taught to count carbohydrates, meaning that they try to estimate the actual amount of carbohydrates (in grams) that they are eating and give themselves specific doses of mealtime insulin to cover it based on an insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio that works for them. Although carbohydrate counting has been shown to improve glycemic control, it is far from an exact science22 and a nearly impossible task for individuals with health literacy and numeracy difficulties.1

More recently, it has been recognized that estimating protein intake is also important in controlling spikes in blood glucose after meals since some of the protein is converted into glucose (albeit more slowly than carbohydrates).23 Protein takes three to four hours to be fully metabolized and some can be converted into blood glucose when digested; therefore, a higher protein intake can contribute to higher blood glucose levels later on, mostly in people who have to inject or pump insulin and are using rapid-acting insulin analogues (such as insulin aspart [Novolog], insulin lispro [Humalog], and insulin glulisine [Apidra]).

To complicate matters, eating a meal with more fat in it has also been shown to increase insulin needs, even when the carbohydrate content is held constant, suggesting that alternative insulin dosing algorithms are needed for higher-fat meals.24 Fat may slightly slow down the absorption of carbohydrate in the meal, but does not change the overall blood glucose peak.25 This point reinforces the fact that chocolate, for example, should not be used to treat low blood sugar because it contains fat which makes the absorption of the candy too slow to bring up a low blood sugar quickly.

Thus, all calories can potentially raise blood glucose at some point, not just those coming from carbohydrates.26,27 This critical point was aptly made in a recent review, which reported that high fat and high protein meals both require more total insulin than a meal with less fat or protein and an identical carbohydrate content.28

Importance of Glycemic Index, Glycemic Load, and Food Insulin Index

Gycemic Index (GI)

How rapidly a carbohydrate is digested affects insulin responses and ability to control blood glucose, as reflected by its glycemic index (GI). The more rapidly a food is broken down, the faster the carbohydrate is turned into blood glucose. To deal with the influx of glucose coming from high-GI carbohydrates, the pancreas must release a large amount of insulin. With diabetes or prediabetes, people may not be able to cover rapid glucose spikes with enough insulin.4

The latest GI database is accessible through www.glycemicindex.com. GI values are usually scaled from 0 to 100, with glucose having a GI of 100. High-GI foods have a GI value of 70 or higher, including almost everything with highly refined flour or added sugars like most breakfast cereals, pretzels, sugary candy, crackers, and bread. White potatoes may be natural, but they have a high GI.

Other carbohydrates cause less of an acute spike in blood glucose levels and are generally easier for the body to handle in moderate amounts. Sweet potatoes, rice (white or brown), oatmeal, and white sugar have GI values in the range of 56 to 69, which gives them a medium GI. Most whole fruits, fructose (fruit sugar), dairy products, legumes (beans), and pasta (white or whole wheat) fall into the low-GI category (55 and lower).

The GI of a particular food can differ from one person to the next, and it can also be affected by the type and amount of carbohydrate, fat, and protein a food contains; the amount of fiber and the nature of any starches in it; its preparation (raw or cooked); its ripeness; and its acidity. For instance, thick linguine has a lower GI value than thin spaghetti. Overcooking in general raises the GI value of foods, so al dente pasta is better. Highly acidic foods like vinegar can lower the GI value of other foods consumed with it. Cold storage increases the resistant starch content (carbohydrates that are hard to digest) by more than a third, and the acid in lemon juice, lime juice, or vinegar will slow gastric emptying (the rate at which the stomach empties its contents into the intestines).

An excessive intake of high-GI carbohydrate foods can increase insulin resistance even in people without diabetes.29 The GI values of foods have mainly been determined in nondiabetic individuals, so their effect may be further exaggerated if someone releases less insulin or has impaired insulin action, and GI values may underestimate rather than overestimate the glycemic spikes caused by most carbohydrate-rich foods in people with diabetes.

Lowering the glycemic effect of meals is beneficial. In overweight adults, insulin resistance can be decreased when they consume a low-GI, whole-grain diet compared to a refined diet. People with type 2 diabetes who follow a low-GI diet (<40) improve their blood glucose control, enhance insulin action, lower bad blood fats, and lose weight.30,31 Such positive results support the notion that GI is an appropriate guide to eating more nutritious foods whether an individual has diabetes, prediabetes, or insulin resistance, or if someone just wants to stay healthy.4

Factor in Glycemic Load (GL)

For carbohydrates, portion size does matter. Glycemic load (GL) is a measure of both GI value and total carbohydrate intake in a typical serving. A GL of 20 or more is high, 11 to 19 is medium, and 10 or less is considered low. Foods that have a low GL almost always have a lower GI value, with some exceptions: watermelon has a high GI value (72), but the carbohydrate content per serving of this fruit is minimal, making its GL (4) low. However, a serving of watermelon is just over a cup. Popcorn also has a higher GI value (72), but it takes a lot to equal a 50 gram serving with a GL of just 8.

Paying attention to GL is even more important with diabetes.32 A high-GI/GL diet will most likely worsen insulin resistance and overtax the body’s ability to supply insulin. People should limit their intake of foods with both a medium or high GI value and a high GL. Any carbohydrate-heavy meal with a high GL will require more insulin, but if the GI value is not also high—as is generally the case with high-fiber foods—blood glucose will stay lower. Legumes, which are rich in protein and fiber, contain carbohydrates with a lower GI. A low-GL, high-fiber diet also raises circulating levels of adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory hormone released by fat cells that can increase insulin action and improve blood glucose control. A low GI/GL diet plan results in weight loss as well.31

|

Use GI and GL to Lower Blood Glucose

- Choose slowly absorbed carbohydrates, not necessarily just a smaller amount of total carbohydrates

- Use GI to identify the best carbohydrate choices, choosing lower GI options

- Limit portion size when eating carbohydrate-rich foods like rice, pasta, beans, or noodles to limit the overall GL

|

Food Insulin Index (FII): An Alternative to GI and GL

One issue with the use of GI to manage blood glucose levels is that the GI does not consider concurrent insulin responses. Some of the same researchers who developed the GI have since attempted to systematically rate insulin responses to common foods instead of simply postprandial glucose spikes, the result being the food insulin index (FII), an alternate method to using GI or carbohydrate counting.33 The results of the initial FII study done on healthy adults without diabetes reported that the relative insulin demand evoked by mixed meals is best predicted by a physiologic index based on actual insulin responses to isoenergetic portions of single foods. They also found that when consuming mixed meals with the same calorie—but varying macro-nutrient—content, carbohydrate counting was of limited value in predicting insulin needs.

The FII is effective for people with diabetes. By way of example, in a recent study done on adults with type 1 diabetes, when compared with carbohydrate counting, use of the FII algorithm significantly decreased glucose levels over 3 hours (measured with continuous glucose monitoring), decreased peak glucose excursions, and improved the percentage of time glucose levels were in a normal range (defined as 72-180 mg/dL, or 4-10 mM) by 30%.34 It also works well in adults with type 2 diabetes, who had less postprandial hyperinsulinemia after eating a low-FII meal, thereby potentially improving insulin resistance and beta-cell function.35

Use of Sugar, Sugar Alcohols, and Other Sugar Substitutes

Foods that are higher in fiber are also, on the whole, lower in added sugars, fat, and calories. White (table) sugar has only a medium-GI value and a low GL, but the health impact of eating a lot of white sugar and other refined carbohydrates is not trivial, particularly given their lack of essential nutrients (besides calories). While it is not necessary to give up refined sugars completely, limiting their intake will help with glycemic control and cholesterol levels as well.

One of the easiest ways to start lowering the sugar content of a person’s diet and improving its glycemic effect is to reduce or eliminate intake of all regular soft drinks, juice, fruit juice drinks, and sugar-sweetened iced tea or lemonade. Substitute water, diet soft drinks (especially the non-caffeinated, non-cola varieties), or other artificially sweetened beverages such as Crystal Light.

As for fructose, there is nothing inherently evil about this simple sugar found in fruit naturally, despite research that has suggested that high-fructose corn syrup in beverages leads to a fatty liver. More likely, it is an excess intake of calories that leads to such health issues, not fructose.36

Some products are touted as “sugar free” because they contain sugar alcohols, which are reduced-calorie sweeteners (usually about half the number of calories as sugar). Blood glucose responses to different sugar alcohols (e.g., sorbitol, xylitol, and lactitol) may vary, but in general, they will have less of an impact on blood glucose levels than other carbohydrates because few are fully metabolized into calories. Although helpful in reducing calories and blood glucose, sugar alcohols are not completely calorie free and may cause a laxative effect in some people.

Finally, using sugar substitutes or other low-calorie sweeteners may help people reduce their calorie intake. They also reduce the intake of high-GI carbohydrates when used in place of sugar to sweeten coffee, tea, cereal, or fruit by adding sweetness without calories. Approved sugar substitutes include saccharin, aspartame, acesulfame potassium, sucralose, neotame, tagatose, and stevia, to name a few. All are considered safe to use and are recommended for people with diabetes by the American Diabetes Association. Sucralose (marketed as Splenda) is one of the most popular ones and has largely replaced aspartame (NutraSweet) in many products, but some people are sensitive to it and experience negative reactions like headaches or stomach upset. Newest to the market is Stevia, a sweetener and sugar substitute extracted from the leaves of the plant species Stevia rebaudiana found in South America. It is 200 times sweeter than sugar, but contains no calories and is a more natural product alternative.

Coffee and Caffeine

Caffeine has no calories, and it stimulates metabolism, so can people with diabetes have regular coffee with breakfast, as well as diet colas, iced tea, and other caffeinated drinks? According to the latest research, rather than improving the chance of avoiding diabetes by drinking coffee, as earlier studies had claimed,37,38 caffeine makes the body more insulin resistant. In lean, obese, and type 2 diabetic people equally, caffeine ingestion equivalent to two to three 8-ounce cups of coffee (5 mg per kg of body weight) per day reduces insulin action by about one-third, and the caffeine-induced decrement is still present after as many as three months of moderate aerobic exercise (which usually increases insulin action).39

The effects of coffee drinking have been studied in people controlling type 2 diabetes with diet, exercise, and oral medications only. Wearing a continuous glucose monitor for 72 hours revealed that when participants drank two cups of coffee daily, their blood glucose rose by 8 percent.40 Caffeine intake also exaggerated the rise in their blood glucose after meals: by 9 percent after breakfast, 15 percent after lunch, and 26 percent after dinner. People with type 2 diabetes who had caffeine before doing an oral glucose tolerance test were also more insulin resistant.41

Interpreting Food Labels and Determining Portion Sizes

Food Labels

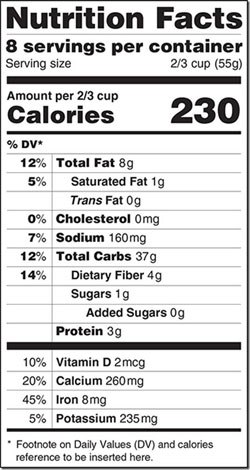

“Serving Size” is always at the top of the nutrition facts label. The nutrition information provided is for the serving size that is stated on the label. Remember that the serving size on the label may not be the same as the portions that people usually eat. To determine the grams of carbohydrate, other macronutrients, or calories in a given product, be sure to check the serving size because serving sizes can be quite small compared to how much people usually consume at one time.

“Serving Size” is always at the top of the nutrition facts label. The nutrition information provided is for the serving size that is stated on the label. Remember that the serving size on the label may not be the same as the portions that people usually eat. To determine the grams of carbohydrate, other macronutrients, or calories in a given product, be sure to check the serving size because serving sizes can be quite small compared to how much people usually consume at one time.

For control of blood glucose, people should focus on the grams of total carbohydrate rather than the indented grams of “Sugars” listed below it. Sugars and fiber are counted as part of the grams of total carbohydrate. If a food contains fiber, however, people should subtract the fiber grams from the total carbohydrate for a more accurate estimate of the carbohydrate content of a food since fiber is not digested—particularly if each serving contains three or more grams of fiber. If a food contains sugar alcohols, subtract one half of the grams of sugar alcohols listed on the label from the total carbohydrate content as they are not fully metabolized. “Added Sugars” as a sub-category of “Sugars” has finally been added to food labels to make it easier for consumers to understand that there may be a health difference between something like sugar naturally occurring in fruit (fructose) and table sugar added to beverages and processed foods.

Manufacturers must list ingredients in order of descending weight. In many products, refined sugar would be listed first if not disguised as four or five different sweeteners that then appear lower on the list. Look for sugar equivalents, such as sucrose, dextrose, high-fructose corn syrup, corn syrup, glucose, fructose, maltose, levulose, honey, brown sugar, and molasses, in the ingredient list. They are all now included as part of the “Added Sugars” and “Total Carbs.”

Portion Control

Although no food is really fully bad, some foods are best when eaten only in small quantities. However, many people experience “portion distortion” and are confused about what an appropriate portion size is because portion and serving sizes frequently differ. People tend to interpret the size of their meal, regardless of how big or small it is, to be an appropriate portion. A “serving” is not the amount a person puts on his or her plate; rather, it is a specific amount of food, defined as cups, ounces or pieces, whereas a “portion” is the amount of a food that a person chooses to eat and can be more or less than a serving. Standardized serving sizes are required to be listed on food labels, but even these are currently being revised by the USDA. On July 26th, 2018, new food labeling requirements go into effect by the FDA. The required changes such as making serving sizes and calories bolder will hopefully help consumes make healthier food choices.

|

Portion versus Serving Sizes

- Many people think the portion in front of them is the appropriate portion size to eat, regardless of how big or small it actually is

- A serving size is a determined amount on a food label and may or may not be the correct portion size

- What is an appropriate portion size varies from person to person

|

Most people do not conceptualize portions very well or have a good sense of their hunger or satiety. For instance, researchers gave participants a lunch of macaroni and cheese every day, and each day they were unknowingly served larger and larger amounts of macaroni and cheese, leading them to eat more each day without realizing it. In another study, participants who ate from secretly refilling bowls ate 73% more soup, but reported feeling no more satiated than those who ate less soup and fewer calories.

Conclusions

There is a lot of controversy around what constitutes a healthy diet, especially for anyone with diabetes. However, a balanced intake of carbohydrates, fats, and protein, along with greater intake of fiber and less processed foods (including refined sugars and carbohydrates) will likely improve the glycemic control and overall health of all individuals with diabetes. Counting carbohydrates may not be as useful as controlling overall calorie intake and choosing foods that require less insulin (as determined with the food insulin index), although use of the glycemic index and glycemic load can be somewhat useful. Sugar substitutes are safe for people with diabetes and can help reduce both glucose spikes and calorie intake. People also need to realize that usual portions of foods are not necessarily the same as an appropriate serving. Overall, it is possible for people with any type of diabetes to improve their overall glycemic control and health with appropriate changes to their diet. It is in fact, incumbent on all of us to try to eat healthier whether or not we have any underlying health conditions.

|

Where can the pharmacy technician be of help with regard to healthy food choices for patients?

Now you hopefully have a better understanding of how nutrition and food choices affect patients with diabetes. You will become a valuable resource to those patients having trouble understanding food labels, for example. When a complex question arises, you should refer patients for counseling with your pharmacist. Many pharmacies now have dietitians available to consult with patients as well, as do hospitals and many ambulatory clinics.

|

References

- American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes 2016 Jan; 34(1): 3-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.34.1.3. Accessed November 4th, 2016.

- Brazeau AS, Leroux C, Mircescu H, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Physical activity level and body composition among adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29:e402-8.

- Mitri J, Hamdy O. Diabetes medications and body weight. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8:573-84.

- Brand-Miller J, McMillan-Price J, Steinbeck K, Caterson I. Dietary glycemic index: health implications. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28 Suppl:446s-9s.

- Otles S, Ozgoz S. Health effects of dietary fiber. Acta scientiarum polonorum Technologia alimentaria. 2014;13:191-202.

- Rose DJ. Impact of whole grains on the gut microbiota: the next frontier for oats? Br J Nutr. 2014;112 Suppl 2:S44-9.

- West CE, Renz H, Jenmalm MC, et al. The gut microbiota and inflammatory noncommunicable diseases: associations and potentials for gut microbiota therapies. The J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:3-13.

- Blaut M. Gut microbiota and energy balance: role in obesity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014:1-8.

- Woodman RJ, Chew GT, Watts GF. Mechanisms, significance and treatment of vascular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: focus on lipid-regulating therapy. Drugs. 2005;65:31-74.

- Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Saturated fat, carbohydrate, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:502-9.

- Gayet-Boyer C, Tenenhaus-Aziza F, Prunet C, et al. Is there a linear relationship between the dose of ruminant trans-fatty acids and cardiovascular risk markers in healthy subjects: results from a systematic review and meta-regression of randomised clinical trials. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:1914-22.

- Kay CD, Kris-Etherton PM, West SG. Effects of antioxidant-rich foods on vascular reactivity: review of the clinical evidence. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2006;8:510-22.

- Micha R, Michas G, Lajous M, Mozaffarian D. Processing of meats and cardiovascular risk: time to focus on preservatives. BMC Med. 2013;11:136.

- Ericson U, Sonestedt E, Gullberg B, et al. High intakes of protein and processed meat associate with increased incidence of type 2 diabetes. Br J Nutr. 2013;109:1143-53.

- Hayes KC, Pronczuk A. Replacing trans fat: the argument for palm oil with a cautionary note on interesterification. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29:253s-84s.

- Sundram K, Karupaiah T, Hayes KC. Stearic acid-rich interesterified fat and trans-rich fat raise the LDL/HDL ratio and plasma glucose relative to palm olein in humans. Nutr Metab. 2007;4:3.

- Bjermo H, Iggman D, Kullberg J, et al. Effects of n-6 PUFAs compared with SFAs on liver fat, lipoproteins, and inflammation in abdominal obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:1003-12.

- Alhazmi A, Stojanovski E, McEvoy M, Garg ML. Macronutrient intakes and development of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012;31:243-58.

- Benatar JR, Sidhu K, Stewart RA. Effects of high and low fat dairy food on cardio-metabolic risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76480.

- Sabate J. Nut consumption and body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:647s-50s.

- Hamdy O, Horton ES. Protein content in diabetes nutrition plan. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11:111-9.

- Brazeau AS, Mircescu H, Desjardins K, et al. Carbohydrate counting accuracy and blood glucose variability in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:19-23. 23. Bell KJ, Gray R, Munns D, et al. Estimating insulin demand for protein-containing foods using the food insulin index. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;9:126.

- Bell KJ, Gray R, Munns D, et al. Estimating insulin demand for protein-containing foods using the food insulin index. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;9:126.

- Wolpert HA, Atakov-Castillo A, Smith SA, Steil GM. Dietary fat acutely increases glucose concentrations and insulin requirements in patients with type 1 diabetes: Implications for carbohydrate-based bolus dose calculation and intensive diabetes management. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:810-6.

- Wolever TM, Mullan YM. Sugars and fat have different effects on postprandial glucose re-sponses in normal and type 1 diabetic subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;21:719-25.

- Bao J, Atkinson F, Petocz P, et al. Prediction of postprandial glycemia and insulinemia in lean, young, healthy adults: glycemic load compared with carbohydrate content alone. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:984-96.

- Peters AL, Davidson MB. Protein and fat effects on glucose responses and insulin requirements in subjects with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:555-60.

- Bell KJ, Smart CE, Steil GM, et al. Impact of fat, protein, and glycemic index on postprandial glucose control in type 1 diabetes: Implications for intensive diabetes management in the continuous glucose monitoring era. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1008-15.

- Brand-Miller J, Buyken AE. The glycemic index issue. Curr Opinion Lipid. 2012;23:62-7.

- Stephenson EJ, Smiles W, Hawley JA. The relationship between exercise, nutrition and type 2 diabetes. Med Sport Sci. 2014;60:1-10.

- Turner-McGrievy GM, Jenkins DJ, Barnard ND, et al. Decreases in dietary glycemic index are related to weight loss among individuals following therapeutic diets for type 2 diabetes. J Nutr. 2011;141:1469-74.

- Brand-Miller JC. Postprandial glycemia, glycemic index, and the prevention of type 2 diabe-tes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:243-4.

- Bao J, de Jong V, Atkinson F, et al. Food insulin index: physiologic basis for predicting insu-lin demand evoked by composite meals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:986-92.

- Bao J, Gilbertson HR, Gray R, et al. Improving the estimation of mealtime insulin dose in adults with type 1 diabetes: the Normal Insulin Demand for Dose Adjustment (NIDDA) study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2146-51.

- Bell KJ, Bao J, Petocz P, et al. Validation of the food insulin index in lean, young, healthy individuals, and type 2 diabetes in the context of mixed meals: an acute randomized crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:801-6.

- Chung M, Ma J, Patel K, et al. Fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, sucrose, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or indexes of liver health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:833-49.

- Ding M, Bhupathiraju SN, Chen M, et al. Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:569-86.

- Jiang X, Zhang D, Jiang W. Coffee and caffeine intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:25-38.

- Lee S, Hudson R, Kilpatrick K, et al. Caffeine ingestion is associated with reductions in glucose uptake independent of obesity and type 2 diabetes before and after exercise training. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:566-72.

- Lane JD, Feinglos MN, Surwit RS. Caffeine increases ambulatory glucose and postprandial responses in coffee drinkers with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:221-2.

- Robinson LE, Savani S, Battram DS, et al. Caffeine ingestion before an oral glucose tolerance test impairs blood glucose management in men with type 2 diabetes. J Nutr. 2004;134:2528-33.

Back to Top