Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Module 5. Understanding Insulin Therapy

IMPORTANT DEFINITIONS

Basal insulin: Basal insulin is insulin that is released in small, consistent increments to maintain stable blood glucose levels throughout the day. Basal insulin therapy mimics the body’s natural production of insulin, which maintains blood glucose stability during periods of fasting, such as overnight.

Bolus insulin: Bolus insulin (often referred to as mealtime insulin) is short-acting or rapid-acting insulin that is used to cover meals or snacks to prevent elevations in glucose related to eating. Bolus insulin therapy mimics the body’s natural production of insulin after eating.

Target blood glucose: Every patient with diabetes has individualized goals for target blood glucose levels that are agreed upon with their health care provider. Normal blood glucose values range broadly, depending on how and when they are measured. Fasting blood glucose is generally the lowest goal number (often 80 to 130 mg/dL), with post-meal blood glucose targets often being less than 180 mg/dL. All goals are individualized on the basis of patient characteristics, risk factors, needs, and preferences.

SMBG: Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) involves a patient checking his or her own blood glucose level with a home monitor. SMBG is especially important for patients using insulin, because this practice allows patients to calculate insulin doses, monitor for potential adverse effects, and assess how well they are maintaining and achieving their target blood glucose levels.

|

INSULIN THERAPY

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus has reached epidemic proportions in the United States (U.S.)1 and it is essential that all health care professionals understand the primary treatment options for this disease. Insulin was discovered in the late 1920’s, and now this hormone serves as a mainstay of treatment for diabetes. Insulin is a life-saving treatment for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), because patients with T1DM have lost the ability to make insulin due to the autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas.2 Many patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) also require insulin therapy as their disease progresses due to a loss of beta cell function over time.3 In fact, approximately 25% to 40% of people with T2DM use insulin as part of their therapy to control the disease.4 The most recent American and European guidelines for the management of patients with T2DM continue to consider basal insulin as second-line treatment, recommending it as an add-on option to metformin and other oral agents.5,6 Simply, if a patient is not achieving glycemic targets with first-line therapy, adding insulin to the regimen can be considered for gaining better control of blood glucose levels in T2DM.5

Insulin is a hormone that plays an important role in glucose, protein, and fat metabolism. Insulin serves as a key to “unlock” cells and allows them to take in energy in the form of glucose, so the cells can function properly. It also stimulates the muscle and liver cells to store glucose (in the form of glycogen), which the body can call upon when it needs fuel, and reduces glucose output from the liver.7,8

Normally, insulin is secreted from the pancreas in small, continuous amounts of “background” insulin to maintain the body’s basal metabolic rate. Larger, bolus doses of insulin are released in response to ingested food to help the body use the carbohydrates that were ingested and maintain constant, normal blood sugar levels.7,8 These normal physiologic processes are impaired in both T1DM and T2DM, and insulin therapy attempts to mimic the body’s natural insulin production. Understandings of this normal background-plus-mealtime insulin secretion pattern of the pancreas has given rise to the basal-bolus concept of insulin therapy.9

The main functions of basal insulin are to suppress hepatic glucose production between meals and overnight and to stimulate lipid and protein synthesis.10 Long-acting and intermediate-acting insulins are used to replace normal, background insulin secretion. Typically, in a basal-bolus model, basal insulin accounts for approximately 50% of the total daily insulin needs. The overall percentage of basal insulin that contributes to the total daily dose (TDD) of insulin, however, varies from patient to patient.

The primary function of bolus insulin is to control increases in blood sugar levels following eating. Rapid-acting insulin or short-acting regular insulin is used to replace normal bolus insulin production. Balancing carbohydrate or meal consumption with bolus insulin replacement requires patient training and education; patients must understand how to balance what they eat at a meal with how much insulin they need to cover the blood sugar surge from that meal. This usually requires self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) several times throughout the day to make sure the insulin dosing is correct; SMBG is usually completed before meals, 1 to 2 hours after meals or exercise, and at bedtime. Because of the nature of their disease, patients with T1DM require full basal and bolus replacement at initiation of therapy. Patients with T2DM are usually able to produce at least some insulin and many oral medications are available to treat deficiencies in insulin production and sensitivity; therefore, patients with T2DM may not require insulin for many years after diagnosis and they may only require once-daily basal insulin injections for several years before requiring any bolus insulin.11

Bolus insulin

Products available for injectable bolus insulin replacements fall into 2 main categories: rapid-acting and short-acting insulins. Injectable rapid-acting insulin analogues include insulin lispro (Humalog), insulin aspart (Novolog, Fiasp), and insulin glulisine (Apidra).12-14 Because of these drugs’ rapid onsets of action of only a few minutes, patients should inject these insulins immediately before a meal or within 15 minutes of eating. Rapid-acting insulins have durations of action of approximately 3 to 4 hours, and, usually, the insulin is cleared from the body before the next meal. This mechanism reduces the opportunity for insulin stacking (accumulation) and associated hypoglycemic (low blood sugar) events. This is an advantage over short-acting regular insulin (Humulin R or Novolin R),15,16 which has a longer onset and is, therefore, administered 30 minutes before a meal. Regular insulin also has a longer duration than rapid-acting insulins, which can increase the risk of between-meal hypoglycemia. All injectable bolus insulin products can be mixed with intermediate-acting NPH insulin (Humulin N or Novolin N).17,18

Inhaled insulin (Afrezza) is a recently available bolus insulin product.19 This agent is used for mealtime insulin replacement and can only be administered in fixed doses in increments of 4, 8, or 12 units. (Each dose can be inhaled separately but added together to achieve the appropriate dosage, as shown in Figure 1.) Baseline pulmonary (lung) function tests are required before using Afrezza, and it should not be used by patients with chronic lung diseases such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or by current smokers. The most common adverse events associated with inhaled insulin are hypoglycemia, cough, and throat pain or irritation.19

| Figure 1. Afrezza (inhaled powdered insulin) Dose Conversion Chart19 |

|

| Reprinted from Afrezza (inhaled insulin powder) [package insert], 2015.19 |

Basal insulin

The 2 main types of basal insulin are intermediate-acting and long-acting insulins. NPH, the only intermediate-acting insulin currently available, is relatively inexpensive and usually dosed once or twice daily. NPH insulin suspension is cloudy white in color due to the zinc additive designed to increase its duration of action. (All other insulins are clear solutions.) NPH is the only insulin that can be mixed in the same syringe as bolus insulin products. When combining insulins, the bolus insulin should be drawn up in the syringe first, followed by NPH.

Currently, 3 long-acting insulin analogue products exist: insulin detemir (Levemir),20 insulin glargine (Lantus U-100; Toujeo U-300),21,22 and insulin degludec (Tresiba U-100 or U-200).23 These products have a long onset of action and a long duration of action. Insulin detemir and U-100 insulin glargine can provide 24-hour basal coverage in many patients, but some individuals may require twice-daily administration to gain a full day of basal coverage. U-300 insulin glargine and insulin detemir, in contrast, are administered once daily given their relatively longer durations of action.

A concentrated U-500 formulation of regular insulin can be used for patients who require large doses of daily insulin, but this formulation is not used often.25 This concentration of insulin has a longer duration of action than U-100 regular insulin and can last up to 24 hours in some patients. The conversion to U-500 regular insulin is usually reserved for patients with extreme insulin resistance (i.e., patients who do not respond to conventional insulin products or doses) and require more than 200 units of insulin daily.25 A dedicated U-500 syringe is available for those patients using a vial rather than a dosing pen.

Pre-mixed insulin products

Pre-mixed, fixed-dose insulin products can be used in some patients and offer the benefits of ease of use and no mixing requirements. These products combine intermediate-acting and short- or rapid-acting insulins in a single vial. There is limited flexibility with these agents in terms of adjusting insulin doses, since the components are present in a fixed ratio.26-31 Table 1 lists available insulin products and note important storage and action profiles.

| Table 1. Insulin Product and Storage Information17-23,25-31 |

| Rapid-acting insulins |

| Brand name |

Generic name |

Product availability |

Onset of action |

Time to peak effect |

Duration of action |

Stability at room temperature (in use) |

| Humalog |

Lispro |

100 U/mL in vial, cartridge, or KwikPen, 200 U/mL in KwikPen |

15 - 30 min |

30 min - 2.5 h |

3 - 6.5 h |

All products: 28 d |

| Novolog |

Aspart |

100 U/mL vial, cartridge, or FlexTouch or FlexPen |

10 - 20 min |

40 - 50 min |

3 - 5 h |

All products: 28 d |

| Apidra |

Glulisine |

100 U/mL vial or SoloStar pen |

25 min |

45 - 48 min |

4 - 5.3 h |

All products: 28 d |

| Short-acting insulins |

| Brand name |

Generic name |

Product availability |

Onset of action |

Time to peak effect |

Duration of action |

Stability at room temperature (in use) |

| Humulin R |

Regular |

100 U/mL vial |

Approximately 30 min |

Approximately 3 h |

Approximately 8 h |

Vial: 31 d |

| Humulin R U-500 |

Regular |

500 U/mL vial or KwikPen |

Approximately 30 min |

1 - 3 h |

Up to 24 h |

Vial: 40 d KwikPen: 28 d |

| Novolin R |

Regular |

100 U/mL vial |

Approximately 30 min |

1.5 - 3.5 h |

Approximately 8 h |

Vial: 42 d |

| Intermediate-acting insulins |

| Brand name |

Generic name |

Product availability |

Onset of action |

Time to peak effect |

Duration of action |

Stability at room temperature (in use) |

| Humulin N |

NPH |

100 U/mL vial or KwikPen |

1 - 2 h |

Approximately 6.5 h |

16 - 24 h or longer |

Vial: 31 d KwikPen: 14 d |

| Novolin N |

NPH |

100 U/mL vial |

90 min |

4 - 12 h |

Up to 24 h |

Vial: 42 d |

| Long-acting insulins |

| Brand name |

Generic name |

Product availability |

Onset of action |

Time to peak effect |

Duration of action |

Stability at room temperature (in use) |

| Lantus |

Glargine |

100 U/mL vial or SoloStar pen |

1.1 h |

No significant peak |

10.8 to 24 h or longer (median 24 h) |

All products: 28 d |

| Toujeo |

Glargine |

300 U/mL SoloStar pen |

Develops over 6 h |

No significant peak |

Greater than 24 h |

SoloStar: 42 d |

| Levemir |

Detemir |

100 U/mL vial and FlexTouch pen |

1.1 - 2 h |

No significant peak |

7.6 - 24 h or longer |

All products: 42 d |

| Basaglar* |

Glargine |

See updates for complete information. |

| Ultra-long-acting insulins |

| Brand name |

Generic name |

Product availability |

Onset of action |

Time to peak effect |

Duration of action |

Stability at room temperature (in use) |

| Tresiba |

Degludec |

100 U/mL FlexTouch pen, 200 U/mL FlexTouch pen |

30 - 90 min |

12 h (minimal) |

42 h |

All products: 56 d |

| Insulin mixtures |

| Brand name |

Generic name |

Product availability |

Onset of action |

Time to peak effect |

Duration of action |

Stability at room temperature (in use) |

| Ryzodeg |

70% degludec, 30% aspart |

100 U/mL FlexTouch pen |

5 - 15 min |

2.3 h |

Longer than 24 h |

FlexTouch: 28 d |

| NovoLog 70/30 |

70% aspart protamine suspension, 30% aspart |

100 U/mL vial or FlexPen |

10 - 20 min |

1 - 4 h |

Up to 24 h |

Vial: 28 d FlexPen: 14 d |

| Humalog 75/25 |

75% lispro protamine suspension, 25% lispro |

100 U/mL vial or KwikPen |

15 - 30 min |

1 - 6.5 h (2.6 h mean) |

Up to 24 h |

Vial: 28 d KwikPen: 10 d |

| Humalog 50/50 |

50% lispro protamine suspension, 50% lispro |

100 U/mL vial or KwikPen |

15 - 30 min |

0.8 - 4.8 h (mean 2.3 h) |

22 h or longer |

Vial: 28 d KwikPen: 10 d |

| Humulin 70/30 |

70% NPH, 30% regular |

100 U/mL vial and KwikPen |

Within 30 min |

1.5 - 6.5 h (mean 3.5 h) |

18 - 24 h |

Vial: 31 d KwikPen: 10 d |

| Novolin 70/30 |

70% NPH, 30% regular |

100 U/mL vial |

30 min |

2 - 12 h (mean 4.2 h) |

Up to 24 h |

Vial: 42 d |

| Inhaled insulin |

| Brand name |

Generic name |

Product availability |

Onset of action |

Time to peak effect |

Duration of action |

Stability at room temperature (in use) |

| Afrezza |

Regular |

4-U, 8-U, and 12-U single-use cartridges |

15 - 30 min |

Median 53 min (SD 74 min) |

160 min |

Opened strips: 3 d Unopened strips: 10 d Inhaler: 15 d |

*Available from Eli Lilly beginning December 15, 2016. Abbreviations: d = days; min = minutes; SD = standard deviation; U = units.

Table developed by: Emily Smith, PharmD Candidate, and Lynn Fletcher, PharmD, Clinical Pharmacist, Health Linc, Purdue University, IN., February 28, 2016. |

Using insulin to treat patients with T1DM

Patients with T1DM need full insulin replacement. Insulin doses are generally based on body weight, and the TDD required is initially calculated as 0.4 to 0.5 units/kg. Lower doses may be needed for patients who still have some insulin-producing pancreatic function remaining.32,33 In general, the TDD is divided into 2 parts: initially, 50% is administered as basal insulin and 50% is administered as bolus insulin. The insulin doses are then titrated according to individual patient response and SMBG data. Insulin dosing is a complex process and requires constant vigilance by the patient. Blood glucose levels need to be checked several times throughout the day to ensure that food intake matches insulin dosing.

Using insulin to treat patients with T2DM

A practical method of initiation of insulin therapy in patients with T2DM is to begin basal insulin at 10 units once daily, in the morning or at bedtime. Patients are generally instructed to select a time of day that best suits their schedule, but, regardless of the preferred time, they must administer the insulin at the same time every day. There are a variety of methods that can be used to effectively titrate basal insulin doses in people with T2DM. One such approach is the “3 by 3 method,” which involves increasing the TDD by 3 units every 3 days until morning (fasting) target blood glucose levels are achieved. Major treatment guidelines provide other recommendations on how to intensify insulin therapy in people with T2DM,5,6 and the choice of intensification scheme is based on clinician experience and patient comfort level with the therapy. Typically, goals are met within a few weeks to the first month of basal insulin therapy, and patients experience reduced symptoms of hyperglycemia without hypoglycemic events. If fasting blood sugar goals are met but the hemoglobin A1C level remains above goal after 2 to 3 months of therapy, mealtime insulin can be added or a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (a non-insulin injectable agent that stimulates the body to produce insulin) may be considered. Some patients with T2DM need bolus, or mealtime coverage, but others may not, depending on how much insulin their pancreas may still be secreting.

Patient management of insulin regimens

Frequent and consistent monitoring of glucose levels helps patients identify patterns with their glucose levels and relationships to medications, exercise, and quality and quantity of food intake. SMBG data is imperative for this level of understanding. Patients should be encouraged to keep a log book to track glucose values, times of day, and insulin doses, as well as food choices and activity levels each day. At least 7 days of data should be used to identify whether a blood glucose pattern can be established.

INSULIN ADMINISTRATION

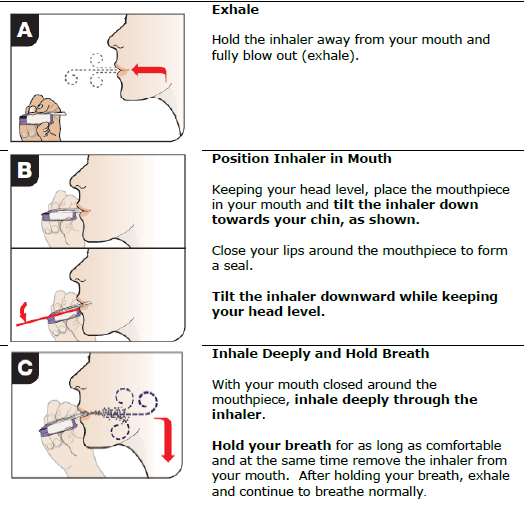

Proper preparation and administration of insulin doses are essential to ensure that patients receive the correct dose and prevent injection-site reactions and other medication-related problems. Tables 2 and 3 provide stepwise instructions for insulin preparation and administration. Insulin absorption can be influenced by several factors in the preparation and administration processes (Table 4), so proper technique is essential.34,35 Afrezza is administered by using the cartridge device and inhaling at a 45-degree angle (Figure 2).19

| Table 2. Guidelines for Preparing an Insulin Dose: Vial and Pen Methods34 |

Using a vial and syringe

- Wash hands with soap and warm water.

- Check the insulin label on the vial to verify the type of insulin to be injected.

- Visually inspect the insulin vial for signs of contamination or degradation (e.g., white clumps, color changes).

- For all cloudy insulins, roll the vial gently back and forth between the hands to re-suspend the insulin.

- Remove the cap and wipe the top of the vial off with an alcohol swab or cotton ball dipped in alcohol.

- Remove the protective coverings over the plunger and needle of the syringe.

- Taking care not to touch the needle, draw up air equal to the insulin dose to be administered into the syringe.

- Inject the air into the insulin vial.a

- With the syringe still inserted, invert the vial and withdraw the insulin dose.b

- Be sure to keep the hub of the needle below the surface of the insulin to prevent creating air bubbles within the syringe.

- If bubbles are present, gently tap the syringe to coax air to the top of the barrel where it can be injected back into the vial.

- Remove the syringe from the vial and self-inject the dose using proper injection technique.

Using a pre-filled insulin pen

- Wash hands with soap and warm water.

- Check the insulin label on the pen to verify the type of insulin to be injected.

- Remove the protective pen cap and visually inspect the insulin for signs of contamination or degradation.

- For all cloudy insulins, invert and roll the pen gently back and forth between the hands to re-suspend the insulin.

- Wipe the rubber stopper with an alcohol swab.

- Attach a needle onto the device according to the manufacturer's directions.

- Remove the outer and inner needle caps.

- Follow any manufacturer's recommendations for priming the device (e.g., 2-unit air shot).

- Making sure pen dose selectors are first set to zero, then dial the insulin dose to be injected.

- Use proper injection technique.

- To deliver insulin when injecting, push down on the plunger button and hold for 5 to 10 seconds.

- Remove the needle from the device after injection to avoid allowing air into the insulin reservoir.

|

aPatients mixing rapid- or short-acting insulin with NPH into the same syringe for injection should be instructed to inject air first into the NPH vial, then into the rapid- or short-acting vial.

bPatients mixing rapid- or short-acting insulin with NPH into the same syringe for injection should be instructed to withdraw the dose of the rapid- or short-acting insulin before the NPH.

*Reprinted with permission from Assemi and Morello34 |

| Table 3. Injecting Insulin34 |

Insulin subcutaneous self-injection technique

- Prepare insulin dose for administration.

- Pinch the area of the skin into which insulin will be injected.

- Insert the needle at a 90-degree angle to the skin in the center of the pinched area. (A 45-degree angle for insertion may be used in small children and very thin adults).

- Release the pinch.

- Press down on the syringe or device plunger to inject insulin.

- Hold the syringe or device in the area for 5 to 10 seconds to ensure full delivery of insulin. This step is particularly important for insulin pen devices.

- Remove the syringe or device.

- Throw needle away in sharps container.

|

| *Reprinted with permission from Assemi and Morello34 |

| Table 4. Factors that Influence Insulin Absorption Rates |

| Insulin-related factor or problem |

Notes |

| Administration route |

- IV administration has the fastest onset of action, IM administration has intermediate onset, and SC has the slowest onset of the available routes of administration

- SC administration is the preferred method of insulin administration

- Insulin suspensions are never administered IM or IV

|

| SC injection site |

- Insulin may be injected into the SC tissue of the abdomen (preferred site), deltoid, thighs, or hips

- Injection sites should be rotated to avoid adverse effects related to injection

- Avoid injecting within a 2-inch radius around the navel

|

| Increased absorption rate |

- Warmth and increased blood flow (e.g., massage, strenuous exercise, fever, sauna, or hot tub) will increase the rate of absorption of insulin from SC tissues

|

| Decreased absorption rate |

- Cold extremities or the application of ice or cold packs to the injection site will decrease the rate of absorption of insulin from SC tissues

|

| Erratic absorption |

- Large insulin doses or improper mixing may cause erratic rates of insulin absorption

- Lipohypertrophy may impair insulin absorption from SC tissues

|

| Abbreviations: IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; SC = subcutaneous. |

| Figure 2. Afrezza Administration19 |

|

| Reprinted from Afrezza (inhaled insulin powder) [package insert], 2015.19 |

Warnings and precautions for the use of insulin

Today’s insulin products are manufactured to be safe and pure, so injection-site reactions are rare. However, some adverse effects can occur related to the injection of insulin. Since insulin is an anabolic hormone, accumulation of fat around the injection site is possible if the patient regularly uses the same injection site. As such, it is important to remind patients to rotate injection sites. The abdominal area is preferred by most patients, but they should be instructed to avoid injecting within 1 to 2 inches around the navel.

Weight gain is related to insulin use, but a healthy diet and regular daily physical activity—which are the most important pieces of diabetes management, regardless of medication therapy—can mitigate this effect.36,37 Regular physical activity improves glycemic control, decreases lipid levels, improves blood pressure, reduces cardiovascular events, decreased mortality risk, and increases quality of life.35

Hypoglycemia is among the most concerning adverse events related to insulin use. Mild-to-moderate hypoglycemia is more common and easier to treat than severe hypoglycemia, which requires medical attention. Recent research indicates an increased risk of cognitive impairment,38 arrhythmias,39 and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality38-43 with severe hypoglycemic episodes. The American Diabetes Association has increased the lower limit of target pre-meal glucose values and now advocates a range of 80 to 130 mg/dL, instead of 70 to 130 mg/dL,7 in order to assist patients with understanding appropriate glycemic targets and avoiding hypoglycemia. Several factors contribute to hypoglycemia, including insufficient caloric intake (e.g., skipped or delayed meals, vomiting), inaccurate calculation of insulin dosages, use of other hypoglycemic medications (i.e., insulin secretagogues), vigorous exercise, and excessive alcohol intake. Early symptoms of hypoglycemia may include trembling, shaking, sweating, heart palpitations, or increased heart rate. Other symptoms (e.g., slow mentation, difficulty concentrating, slurred speech, uncoordinated movements, dizziness) may occur as hypoglycemia worsens. Education about hypoglycemia prevention and awareness are critical for helping patients avoid serious complications related to insulin use.

Treating mild-to-moderate hypoglycemia

Mild-to-moderate hypoglycemia can usually be reversed rapidly, often within 5 to 10 minutes. Using the “Rule of 15” (Table 5), blood glucose concentrations rise quickly to restore normal levels without over-correcting, which could lead to elevated glucose concentrations and a dangerous blood glucose “roller coaster”. To prevent and treat mild-to-moderate hypoglycemia, people who use insulin should always carry a fast-acting glucose source with them at all time.32

| Table 5. Treating Mild-to-Moderate Hypoglycemia with the "Rule of 15"*32 |

| Step |

Directions |

| 1 |

Using a glucose monitor, test to determine if blood glucose is below 70 mg/dL |

| 2 |

Eat 15 grams of simple, concentrated carbohydrates |

| 3 |

Wait 15 minutes |

| 4 |

Check blood glucose again |

| 5 |

If blood glucose is still below 70 mg/dL, consume an additional 15 grams of carbohydrates |

| 6 |

Consume a light snack or a meal if it is mealtime |

| *This method of treatment is appropriate if a patient's blood glucose level is between 50 and 70 mg/dL. If the blood glucose level is below 50 mg/dL and the patient can swallow, do not follow the "Rule of 15." Instead, the patient should consume 20 to 30 grams of carbohydrates. |

An example of a fast-acting glucose source is 4 ounces (1/2 cup) of fruit juice or non-diet soda. Foods that are high in fat, such as chocolate, doughnuts, potato chips, and pizza, are poor choices for treating hypoglycemia. Fatty foods slow carbohydrate absorption, which delays glucose correction and adds unnecessary calories to a patient’s diet.39 However, if these foods are the only sources available, patients should eat them, realizing that symptoms may take longer to resolve.

Treating severe hypoglycemia

Untreated mild-to-moderate hypoglycemia can lead to severe hypoglycemia. Severe hypoglycemia may result in unconsciousness, coma, seizures, and the inability to swallow. This condition should be treated with injectable glucagon.44 Unconscious patients experiencing severe hypoglycemia cannot swallow. Force-feeding food or liquid to an unconscious person is unsafe and can lead to choking.

Patients using insulin therapy should possess a glucagon emergency kit. Glucagon emergency kits are available only by prescription. The kit contains a 1-mg ampule of glucagon, a syringe filled with diluent, and administration directions. Glucagon, a natural counter-regulatory hormone to insulin, works quickly to increase blood glucose concentrations. The glucagon mixing and administration instructions may be confusing during an emergency. To prevent confusion in a stressful situation, it is vital to educate people around the patient (e.g., family, coworkers, close friends, teachers, caregivers) how to prepare and administer glucagon before an actual emergency arises. Encourage them to practice the process of glucagon administration ahead of time so they will be prepared if an emergency arises. Annual re-education is a practical recommendation.44

Figure 3 contains a summary of the steps for treating severe hypoglycemia with glucagon. Because glucagon can cause vomiting, an unconscious individual should be turned on his or her side before glucagon is administered to prevent choking. The usual doses are 1 mg for adults and children older than 5 years of age who weigh more than 44 pounds (20 kg) and 0.5 mg for children younger than 5 years of age who weigh less than 44 pounds (20 kg). Glucagon usually works within 5 to 10 minutes, but the effects are short-lived. If no response is seen after 5 to 10 minutes, a second injection may be given. If that dose is ineffective, the caregiver should call 911 immediately. Once the person is conscious and able to swallow, the caregiver should give him or her a carbohydrate-containing liquid (e.g., juice, milk, non-diet soft drink) followed by a carbohydrate- and protein-rich snack (e.g., small sandwich and/or crackers with peanut butter). Regular blood glucose monitoring is necessary for the 24 hours after an episode of severe hypoglycemia, as well as adequate food intake to replenish liver glycogen stores. The patient’s primary care provider should be informed of the episode.44

| Figure 3. Treatment of Severe Hypoglycemia with a Glucagon Kit44 |

|

Glucagon Emergency Rescue Kit. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Glucagon_emergency_rescue_kit.JPG

Published December 6, 2006 by Mbbradford. Accessed January 12, 2017.

|

Use a glucagon emergency kit only if the person is unconscious or unable to swallow.

Follow instructions on the brightly colored box carefully.

Reconstitute 1 mg of glucagon in 1 mL of sterile water:

- Mix

- Turn patient on his or her side

- Inject into arm, abdomen, or buttocks

Administer the following amounts of glucagon:

- 1 mL for adults and children older than 5 years of age who weigh more than 44 lb (20 kg)

- 0.5 mL for children who weigh less than 44 lb (20 kg), irrespective of age

Reconstituted glucagon must be used right away - discard any unused drug.

When the person is able to swallow, give a carbohydrate liquid such as juice, soda, or milk followed by a carbohydrate- and protein-rich snack such as crackers with peanut butter or a meat sandwich.

Response generally takes 5 to 20 minutes.

IF THE PERSON DOES NOT RESPOND TO GLUCAGON, SEEK MEDICAL ATTENTION IMMEDIATELY BY CALLING 911.

|

Remind patients to regularly check expiration dates of their glucagon kits. It is a good practice to dispense a new glucagon prescription annually. Although some patients may not use their glucagon emergency kits for many years, every person who uses insulin therapy should have a kit available and keep it easily accessible. The kits should be stored in several places, such as in the bedroom or in a purse, a desk, a briefcase, or a backpack, and individuals around the patient should know where the kits are located.

Patients with repeat hypoglycemic episodes can develop hypoglycemia unawareness, a condition characterized by progressive loss of symptoms of the autonomic response to hypoglycemia, such as sweating, tremor, anxiety, and palpitations.45 The loss of these symptoms as warning signs may result in inappropriate action by the person and allow blood glucose levels to fall dangerously low. However, hypoglycemic unawareness can, in some cases, be reversed by strict avoidance of hypoglycemia for even a few days.46 When establishing treatment goals for patients at high risk for hypoglycemia, it may be prudent to allow glycemic targets to be a bit higher than normal to help avoid severe hypoglycemia. The benefits and goals of insulin therapy must outweigh its risks and be aligned to a patient’s needs and preferences.

BARRIERS TO INSULIN USE

Despite the advances and improved safety of newer insulin formulations, patients may still be reluctant to initiate insulin therapy. A systematic review evaluating 25 studies (15 qualitative and 10 quantitative) indicated that barriers to insulin use tend to fall into 3 main categories: patient-related, health care provider-related, and system-related.47 The 3 most common barriers for patients were fear of painful injections, adverse effects of insulin, and the perception that insulin use signals the end stages of diabetes. All of these patient barriers can be overcome with proper patient education and effective patient-provider communication. Table 6 lists common barriers and provides practical talking points and solutions that providers can use to address and overcome the barriers.47-53

| Table 6. Insulin Use: Perceived Barriers and Solutions47-53 |

| Patient-related barriers |

Talking points to share with patients |

Solutions/actions |

| Fear of pain and injection |

Abdominal fat tissue has very few nerves, so injections should not be painful.

The fingertips contain more nerves than fat tissue, so blood glucose testing on fingertips may be more painful than insulin injections. |

Demonstrate injection technique in clinic. |

| Adverse effect: hypoglycemia |

Low blood sugar levels can be prevented with longer-acting basal inulin products and with proper dosing of insulin and self-monitoring of glycemic control. |

Educate patients on prevention and treatment of hypoglycemia. |

| Adverse effect: weight gain |

Weight gain associated with insulin use can be prevented by regular, daily physical activity that the patient enjoys (e.g., biking, walking, swimming, dancing). |

Help patients identify a daily activity and a schedule that is easy to maintain. |

| Perception that insulin is used for end-stage diabetes |

This fact may have been true 30 to 40 years ago when only sulfonylureas and insulin were available for use. Now, the ADA recommends that basal insulin be considered as second-line treatment as an add-on to metformin in addition to healthy lifestyle changes. |

Share and discuss the most recent ADA guidelines with patients. Find these guidelines annually at www.diabetes.org. |

| Inconvenience of insulin therapy |

Most people with T2DM who add insulin to their treatment regimen only require 1 injection daily. Insulin pens can be used for added convenience. |

Educate patients on the use of basal insulin and insulin pens. |

| Administration difficulty |

Insulin is available in vials, pens, and pumps. Pens are the easiest to use, especially for patients who frequently travel, but the vial/syringe method is also quite simple with proper training. |

Demonstrate easy steps of insulin administration. |

| Health care provider-related barriers |

Contributing factors/reasons for barriers |

Solutions/actions |

| Poor knowledge, experience, and skills |

Patients will feel more confident about using insulin if the provider is confident about its use and benefits. |

Improve practical education and training efforts, including learning about the variety of insulin products available and the ease of injections, monitoring, and pattern management.

Consider attending clinical in-services by content experts and diabetes educators. |

| Physician inertia |

Insulin is an add-on to oral therapies to aid in controlling diabetes. |

Become familiar with current guidelines and algorithms for treatment.

Learn about and demonstrate the ease of insulin administration and monitoring. |

| Lack of patient adherence |

Patients will feel more confident about using insulin if the provider is confident about its use, adherence, and benefits. |

Learn about and demonstrate the ease of insulin administration and monitoring. |

| Fear of patient anger |

Insulin is an add-on to oral therapies to aid in controlling diabetes. |

Become familiar with current guidelines and algorithms for treatment and share these with patients.

Learn about and demonstrate the ease of insulin administration and monitoring. |

| Risks of hypoglycemia and weight gain |

Both hypoglycemia and weight gain can occur with insulin use and patient and providers may have apprehensions about how insulin will affect the overall treatment goals.

Hypoglycemia may be prevented with longer-acting basal inulin products, proper dosing, and frequent monitoring.

Weight gain may be prevented by regular, daily physical activity that the patient enjoys (e.g., biking, walking, swimming, dancing). |

Educate patients on prevention and treatment of hypoglycemia. Help patients identify a daily activity and a schedule that is easy to maintain. |

| Language barriers |

Proper, effective communication is only possible if the patient has adequate health literacy and language skills. Ideally, medical and health information and instructions will be provided in a patient's native language. |

Identify language or literacy issues and seek assistance from a family member or caregiver who is multilingual or can assist with literacy challenges.

Refer patients to diabetes educational services.

Review instructions in a patient's native language. |

| System-related barriers |

Contributing factors/reasons for barriers |

Solutions/actions |

| Time |

Inadequate time during physician office visits impedes optimization of outcomes.

Patients may be willing to attend an educational class or a one-on-one session with a diabetes educator.

Insulin administration can be taught outside of the clinical setting. |

Refer patients to diabetes educational services. |

| Abbreviations: ADA = American Diabetes Association; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. |

Provider-related barriers tend to be associated with a lack of knowledge and concerns about insulin’s adverse events, as well as fear that patients will either not be willing to use it or have poor adherence.47,50-53 With the advances in insulin therapy, adding basal insulin to an oral regimen can offer considerable control of blood glucose levels and minimize the risks of weight gain and hypoglycemia. A simple solution to these barriers may be to provide the health care provider with diabetes education and training that includes the pathophysiology of diabetes and the benefits and ease of insulin use, as well as strategies for supporting patient-directed blood glucose pattern management. Education of all health care professionals in the areas of diabetes management will lead to providers who are confident in their abilities to effectively prescribe and manage insulin in the appropriate patient.

Empowering patients to control diabetes

A personalized approach to care is recommended to help patients achieve effective glycemic control as part of diabetes management.5 Health care professionals should also engage in frank conversations with patients about the progressive nature of diabetes, factors that can affect patient health such as smoking, current glycemic control status, current or potential complications, and how to prevent complications by adopting healthy lifestyle habits; this education will serve to support and empower patients, which is fundamental to diabetes control.54,55 Empowerment encompasses listening, acknowledging, believing, and guiding the patient. Every member of the health care team can listen to patients’ fears, concerns, and interests and help them identify a regimen that will best suit their needs, preferences, and lifestyles. Acknowledging a patient’s concerns and discussing his or her apprehensions includes that patient as a key member of the health care team, and it is helpful in breaking down many barriers. Pharmacy technicians can use patient concerns as an opportunity to refer patients to a pharmacist for counseling and education.

Discussing treatment options and acknowledging and addressing barriers are essential to supporting patient adherence to insulin therapy. Helping patients understand that, ultimately, they are in charge of their diabetes is vital to optimizing care. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can assist patients by providing tools, education, medication, and knowledge, but it is incumbent on patients to use this information to make positive choices and manage their diabetes. Health care professionals can support patients and guide them toward achieving their goals, but the ultimate goal of patient empowerment is that patients will modify their own behavior and make better decisions about their health care.54,55

Once barriers to insulin therapy are addressed and patients are educated, a positive impact from initiating insulin therapy occurs almost immediately. A persistent titration of basal insulin coupled with daily SMBG is among the fastest ways that patients can achieve measurable differences in their diabetes control. Improvements in hyperglycemic symptoms of poor energy, frequent urination, and excessive thirst soon follows. Glycemic control has been shown to prevent or reduce long-term complications, and reaching blood glucose targets has long-lasting effects: the benefits of previous glycemic control last over a decade in preventing complications.56-60 Insulin use should not be feared, and it can very quickly help control diabetes. The benefits of insulin use should be explained to patients and they should be supported as they initiate and adjust therapy. Table 7 summarizes key educational components and counseling points that pharmacists may use when speaking with patients.

| Table 7. Counseling Points Pharmacists May Use for Patients Who Use Insulin Therapy32,34-37,56-60 |

Benefits of insulin use

- Easy to use

- If injections are done properly, they should not hurt

- Quickly controls blood glucose values

- Direct, objective impacts on glycemic control can be observed daily as patients slowly, but consistently, titrate daily insulin dosages to achieve treatment goals

- Often, once-daily basal insulin coupled with a healthy diet and activity plan can effectively control diabetes for several years

Key issues with insulin administration

- Inspect insulin before injection to ensure that the correct type of insulin and dose is being administered

- Insulin that is being used can be stored at room temperature

- Insulin that is not in use should be stored in a refrigerator

Preventing and treating of hypoglycemia

- Do not skip meals

- Test blood glucose regularly

- Only take the prescribed insulin dose

- Carry a glucose source on your person at all times

- Understand the "Rule of 15" method of treating hypoglycemia

Preventing or minimizing weight gain

- Eat healthy, fiber-rich meals that include fresh vegetables, whole grains, and lean meat

- Identify ways to become more physically active that are enjoyable

|

Pharmacy technicians are an integral part of the pharmacy team and can identify potential counseling opportunities during interactions with patients. For patients who use insulin, ask the following open-ended questions to assess their comfort levels with insulin therapy and discern if a pharmacist consultation is needed:

- How does your insulin work?

- What difficulties do you have with your injections?

- How are you tracking your blood sugars?

- How often do you test your blood sugars? What do the results mean to you?

- How have you been feeling since you started your insulin?

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Diabetes Translation. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed December 9, 2016.

- Cefalu WT, Rosenstock J, LeRoith D, Riddle MC. Insulin’s role in diabetes management: after 90 years, still considered the essential “black dress.” Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12):2200-2203.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837-853.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Age-adjusted percentage of adults with diabetes using diabetes medication, by type of medication, United States, 1997-2011. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/meduse/fig2.htm. Updated November 20, 2012. Accessed December 9, 2016.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):140-149.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl1):S1-112.

- Powers AP, D’Alessio D. “Chapter 43: Endocrine Pancreas and Pharmacotherapy of Diabetes Mellitus and Hypoglycemia.” In: Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2011.

- Moghissi E, King AB. Individualizing insulin therapy in the management of type 2 diabetes. Am J Med. 2014;127(10 Suppl):S3-10.

- McCall AL. “Chapter 13: Insulin Therapy and Hypoglycemia.” In: Leahy J, Cefalu W, eds. Insulin Therapy. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA(1c). Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):881-885.

- Bethel MA, Feinglos MN. Basal insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(3):199-204.

- Humalog [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2015.

- Novolog [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2015.

- Apidra [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis; 2015.

- Humulin R [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2015.

- Novolin R [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2012.

- Humulin N [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2015.

- Novolin N [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2015.

- Afrezza (inhaled insulin powder) [package insert]. Danbury, CT: MannKind Corp; 2015.

- Levemir [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2015.

- Lantus [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis; 2015.

- Trujeo (insulin glargine U300) [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis; 2015.

- Tresiba [package insert]. Bagsvaerd, Denmark: Novo Nordisk; 2016.

- FDA approves Basaglar, the first “follow on” insulin glargine product to treat diabetes [FDA News Release]. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; December 16, 2015. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm477734.htm. Accessed March 2, 2016.

- Humulin R U-500 [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2016.

- Humulin 70/30 [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN; Eli Lilly and Company; 2015.

- Novolin 70/30 [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2015.

- Humalog Mix 50/50 [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2015.

- Humalog Mix 75/25 [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2015.

- Novolog Mix 70/30 [package insert]. Bagsvaerd, Denmark: Novo Nordisk; 2015.

- Ryzodeg 70/30 [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2015.

- Kroon LA, Williams C. “Chapter 53: Diabetes Mellitus.” In: Alldredge BK, Corelli RL, Ernst ME, et al, eds. In: Koda-Kimble and Young’s Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- American Diabetes Association. Practical Insulin: A Handbook for Prescribing Providers. 3rd ed. 2011.

- Assemi M, Morello CM. “Chapter 47: Diabetes Mellitus.” In: Berardi RR, Ferreri S, Hume AL, et al, eds. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs: An Interactive Approach to Self-Care. 16th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2009.

- Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):e147-167.

- Morello CM, Christopher ML, Ortega L, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with a collaborative pharmacist-endocrinologist diabetes intense medical management “tune up” clinic in complex patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(1):8-16.

- Evert AB, Boucher JL, Cypress M, et al; American Diabetes Association. Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3821-3842.

- Feinkohl I, Aung PP, Keller M, et al; Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes Study (ET2DS) Investigators. Severe hypoglycemia and cognitive decline in older people with type 2 diabetes: the Edinburgh type 2 diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(2):507-515.

- Chow E, Bernjak A, Williams S, et al. Risk of cardiac arrhythmias during hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk. Diabetes. 2014;63(5):1738-1747.

- Elwen FR, Huskinson A, Clapham L, et al. An observational study of patient characteristics and mortality following hypoglycemia in the community. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1):e000094.

- Zoungas S, Patel A, Chalmers J, et al; ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(15):1410-1418.

- McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Ziegenfuss JY, et al. Increased mortality of patients with diabetes reporting severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(9):1897-1901.

- Khunti K, Davies M, Majeed A, et al. Hypoglycemia and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in insulin-treated people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(2):316-322.

- Pearson T. Glucagon as a treatment of severe hypoglycemia: safe and efficacious but underutilized. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(1):128-134.

- Oltmanns KM, Deininger E, Wellhoener P, et al. Influence of captopril on symptomatic and hormonal responses to hypoglycaemia in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(4):347-353.

- Raskin P, Klaff L, Bergenstal R, et al. A 16-week comparison of the novel insulin analog insulin glargine (HOE 901) and NPH human insulin used with insulin lispro in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(11):1666-1671.

- Ng CJ, Lai PS, Lee YK, et al. Barriers and facilitators to starting insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(10):1050-1070.

- Edelman S, Pettus J. Challenges associated with insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2014;127(10 Suppl):S11-16.

- Wallia A, Molitch ME. Insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2014;311(22):2315-2325.

- de Pablos-Velasco P, Parhofer KG, Bradley C, el al. Current level of glycaemic control and its associated factors in patients with type 2 diabetes across Europe: data from the PANORAMA study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;80(1):47-56.

- Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger PM. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational Global Attitudes of Patients and Physicians in Insulin Therapy study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):682-689.

- Ratanawongsa N, Crosson JC, Schillinger D, et al. Getting under the skin of clinical inertia in insulin initiation: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Insulin Starts Project. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(1):94-100.

- Funnell MM. Overcoming barriers to the initiation of insulin therapy. Clin Diabetes. 2007;25(1):36-38.

- Baghbanian A, Tol A. The introduction of self-management in type 2 diabetes care: a narrative review. J Educ Health Promot. 2012;1:35.

- Tol A, Alhani F, Shojaeazadeh D, et al. An empowering approach to promote the quality of life and self-management among type 2 diabetic patients. J Educ Health Promot. 2015;4:13.

- Morello CM, Chynoweth M, Kim H, et al. Strategies to improve medication adherence reported by diabetes patients and caregivers: results of a Taking Control of Your Diabetes Survey. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(2):145-153.

- Nathan DM; for the DCCT/EDIC Research Group. The diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study at 30 years: overview. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):9-16.

- ACCORD Study Group; ACCORD Eye Study Group; Chew EY, Ambrosius WT, Davis MD, et al. Effects of medical therapies on retinopathy progression in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(3):233-244.

- Gore MO, McGuire DK. The 10-year post-trial follow-up of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS): cardiovascular observations in context. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2009;6(1):53-55.

- Zoungas S, Chalmers J, Neal B, et al; ADVANCE-ON Collaborative Group. Follow-up of blood-pressure lowering and glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(15):1392-1406.

Back to Top