Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Targeting Underserved Populations for Diabetes Screening and Education

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a metabolic disease characterized by high blood glucose levels, typically resulting from a combination of persistent insulin resistance and progressive beta-cell failure.1 Untreated or inadequately controlled diabetes can lead to a plethora of long-term complications including cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, kidney disease, and peripheral neuropathy.2 Prediabetes is a condition in which individuals have high blood glucose levels, but not high enough to meet the criteria for a diagnosis of diabetes. People with prediabetes are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, but not all will progress to diabetes.3

Clinical evidence indicates that lifestyle modifications and education can prevent or delay type 2 diabetes.4-9 Additional evidence shows that, once diagnosed, early, intensive treatment can prevent long-term complications of the disease.10 Unfortunately, the prevalence of diabetes remains high, and disparities exist in the screening and management of the disease. Therefore, it is critical that pharmacists understand how and why these disparities exist and how to effectively target these disparities in the screening, prevention, and management of diabetes in underserved populations.

DIABETES STATISTICS IN UNDERSERVED POPULATIONS

Due to the aging of the population and the increasing rates of overweight and obesity in the United States (U.S.), the prevalence of diabetes has increased dramatically over the last few decades. As of 2017, more than 30 million people (9.4% of the population) in the U.S. have diabetes.3 Of those, 23.1 million people are diagnosed, leaving 7.2 million people with undiagnosed diabetes. It is estimated that an additional 34% of adults aged 20 years or older (84.1 million) in the U.S. have prediabetes. However, only 11% of those with prediabetes are aware that they have the condition.11 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tabulate and report the percentage of U.S. adults that have ever been told by a health care professional that they have prediabetes: these estimates range from 4.7% in Vermont and Wyoming to 10.6% in Hawaii. These data suggest that awareness of prediabetes in the U.S. is quite low across the entire population, and awareness in underserved populations is likely even lower. Without weight loss and physical activity, 15% to 30% of people with prediabetes will develop type 2 diabetes within 5 years.12

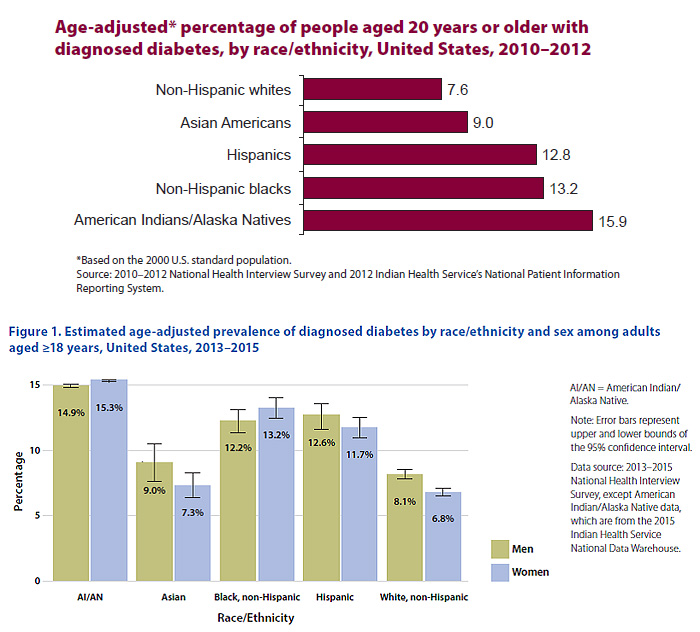

Type 2 diabetes disproportionately affects people of certain racial and ethnic groups, including Asian-Americans, Hispanics, non-Hispanic blacks, and American Indians/Alaska Natives (Figure 1).3 A closer look within these categories indicates that, among Hispanic adults, the age-adjusted rate of diagnosed diabetes was 8.5% for Central and South Americans, 9.0% for Cubans, 13.8% for Mexican Americans, and 12.0% for Puerto Ricans. Among Asian American adults, the age-adjusted rate of diagnosed diabetes was 4.3% for Chinese, 8.9% for Filipinos, 11.2% for Asian Indians, and 8.5% for other Asians. Among American Indian and Alaska Native adults, the age-adjusted rate of diagnosed diabetes varied by region, ranging from 6.0% for Alaska Natives to 22.2% for American Indians in the southwest U.S.3

Figure 1: Racial and Ethnic Differences in Diagnosed Diabetes Among People Aged 20 Years or Older, United States, 2010-20123 |

Analyses of data from 664,969 adults in the National Health Interview Survey indicate that the prevalence and incidence of diabetes across the entire U.S. population did not change significantly in the 1980s, but it rose consistently each year between 1990 and 2008 and then leveled off again between 2008 and 2012. Incidence rates among non-Hispanic black and Hispanic adults increased at rates significantly greater than for non-Hispanic white adults. In addition, the rate of increase in the prevalence of diabetes was significantly higher in adults with a high school education or less compared to adults with more than a high school education.13

These groups with disproportionately higher rates of diabetes also make up a disproportionate share of the poor and uninsured. Poverty rates in the U.S. are 25.9% for American Indians, 22.1% for African Americans, and 21.2% for Hispanics; the rate is 7.5% for non-Hispanic whites. Those living in poverty face many issues that contribute to poor health, which may include substandard housing, low-income neighborhoods, close access to fast food restaurants but a lack of grocery stores that carry healthy food choices, and a lack of sidewalks and crime-free parks. These barriers to healthy eating and physical activity increase the risk of overweight and obesity and contribute to the development of diabetes.14

In addition, many groups with disproportionately higher rates of diabetes do not have sufficient access to health care, including preventive health and wellness, or they may receive a lower quality of care than non-minorities.14 Of the non-elderly population in the U.S., African-Americans, Hispanics, American Indians and Alaskan Natives all have higher uninsured rates compared to non-Hispanic whites. Compared to insured patients, uninsured patients with diabetes are less likely to receive proper diabetes standards of care, including routine glucose monitoring, routine foot exams to screen for neuropathy, or routine eye exams to screen for retinopathy.

The highest rates of diabetes are found in the American Indian population. American Indians also have among the highest rates of poverty among all ethnic groups, earning wages of approximately half of what the average American earns. Poverty rates are highest on Indian reservations. The mortality rate due to diabetes is 3 times higher for American Indians than for the general U.S. population.14

CURRENT GUIDELINE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DIABETES SCREENING AND PREVENTION

Because of the increased prevalence of diabetes, the fact that many patients do not experience symptoms of hyperglycemia, and evidence showing that early treatment is effective at preventing long-term complications of the disease, it is crucial that patients with risk factors for diabetes be tested for the disease. Diagnostic testing for diabetes is completed by a health care provider by measuring fasting plasma glucose (FPG), 2-hour plasma glucose after an oral glucose tolerance test, or glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C).2 Glucose criteria for the diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes can be found in Table 1.2 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has proposed criteria for diagnostic testing in both asymptomatic adults and children (Table 2).2 These criteria have broadened over the last decade in an attempt to better identify undiagnosed, asymptomatic individuals early in the disease process. Although the ADA does not yet recommend universal testing for all asymptomatic adults, they do recommend testing for all adults over the age of 45 years and for younger adults who have at least 1 risk factor.

| Table 1: Criteria for the Diagnosis of Prediabetes and Diabetes2 |

| Prediabetes* |

Diabetes* |

- FPG 100 – 125 mg/dL, or

- 2-hour PG 140 – 199 mg/dL after OGTT, or

- A1C 5.7% – 6.4%

|

- FPG ≥ 126 mg/dL, or

- 2-hour PG ≥ 200 mg/dL after OGTT, or

- A1C ≥ 6.5%, or

- Random PG ≥ 200 mg/dL with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemia crisis

|

*Results should be confirmed by repeat testing unless there is unequivocal hyperglycemia.

Abbreviations: A1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test;

PG, plasma glucose. |

| Table 2: Criteria for Testing for Diabetes and Prediabetes in Asymptomatic People2 |

| Adults |

- Overweight or obese* adults with 1 or more of the following risk factors:

- Prediabetes on previous testing

- First-degree relative with diabetes

- High-risk race/ethnicity (e.g., African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander)

- Women who were diagnosed with GDM

- History of CVD

- Hypertension

- HDL < 35 mg/dL and/or TG > 250 mg/dL

- Women with PCOS

- Physical inactivity

- Other condition associated with insulin resistance (e.g., acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia)

- All adults ≥ 45 years old

- If results are normal, repeat screening every 3 years at a minimum. If results indicate prediabetes, repeat screening annually.

|

| Children |

- Overweight (BMI > 85th percentile for age and sex, weight for height > 85th percentile, or weight > 120% of ideal for height) with 2 or more of the following risk factors:

- Family history of type 2 diabetes in first- or second-degree relative

- High-risk race/ethnicity (e.g., African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander)

- Signs of insulin resistance or conditions associated with insulin resistance (e.g., acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, PCOS)

- Maternal history of diabetes or GDM during the child's gestation

- Age of initiation: age 10 years or at onset of puberty, if puberty occurs earlier

- If results are normal, repeat screening every 3 years.

|

*BMI ≥ 25 kg/m² or ≥ 23 kg/m² in Asian Americans.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GDM, gestational diabetes; HDL,

high density lipoprotein; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; TG, triglycerides. |

However, many people who are at risk for diabetes do not know they are at risk and do not get tested. Therefore, screening for high-risk patients is crucial. The ADA suggests that screening for type 2 diabetes with an informal assessment of risk factors be considered in all asymptomatic adults.2 They offer a screening instrument (available as a printed or electronic option) that pharmacists can easily use in any practice environment, including community pharmacies, brown-bag events, or community outreach programs (Figure 2).2 The screening instrument can be completed directly by the patient or with the help of a pharmacist or other health care provider. The instrument helps the patient identify his or her risk for type 2 diabetes by evaluating risk factors such as weight, activity level, age, presence of high blood pressure, and family history. It is important to note that the screening tool is not a diagnostic tool: it does not give a patient a diagnosis of diabetes, but it instead provides guidance regarding the patient's risk for having the disease. After answering 7 questions, a score is calculated that can range from 1 to 10. Individuals scoring 5 or higher are at an increased risk of having diabetes or prediabetes and should see a health care provider to complete diagnostic testing.

Figure 2: American Diabetes Association – Diabetes Risk Test2 |

HEALTH DISPARITIES IN THE SCREENING, DIAGNOSIS, AND MANAGEMENT OF DIABETES

A health disparity is defined as "a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion."15

Health disparities in the U.S. are common. On the basis of information gathered in 2008, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that approximately 33% of the population (more than 100 million people) identified themselves as belonging to a racial or ethnic minority population. Women (154 million people) comprised 51% of the population. Approximately 23% of the U.S. population (70.5 million people) lived in rural areas and approximately 12% (36 million people) had a disability.16

Numerous studies have linked health disparities with significant underdiagnosis and poor screening for diabetes and prediabetes. A study conducted by Stark Casagrande et al evaluated the prevalence of diabetes screening according to demographic factors using data from more than 35,000 patients. The overall prevalence of having a blood test for diabetes in the past 3 years was 42.1% from 2005 to 2006, 41.6% from 2007 to 2008, and 46.8% from 2009 to 2010. The prevalence was higher for older patients, women, non-Hispanic whites, and those with more education and income. Testing was less prevalent in minorities and those with lower socioeconomic status.17

Possible health disparities in diabetes screening between Asian Americans and adults from other ethnic groups were evaluated in a cross-sectional analysis of pooled data from 45 U.S. states from 2012 to 2014. In a population of 526,000 adults who were eligible to receive diabetes screening according to the ADA guidelines, Asian Americans were 34% less likely to receive recommended screening compared to non-Hispanic whites, making Asian Americans the least likely racial or ethnic group to receive recommended diabetes screening.18

Severe mental illness is also associated with an elevated risk for type 2 diabetes, with antipsychotic medications contributing to this risk.19 The ADA recommends annual diabetes testing for patients treated with antipsychotic medications. A recent study examined diabetes screening among publicly insured adults with severe mental illness who were taking antipsychotic medications using data from the California Medicaid system that included more than 50,000 study participants. The results showed that only 30.1% of patients received diabetes-specific screening.20

Culture and society also play key roles in the type 2 diabetes epidemic. There are many trends related to food choices in the U.S. that contribute to diabetes, including large portion sizes, increased calorie intake from sweetened beverages and refined carbohydrates, increased cost of healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables compared to unhealthy energy-dense foods, and poor food options in both rural and urban environments. Although great variation exists around the country, many of these issues surrounding poor food choices can be linked to underserved populations.

Food insecurity is "the unreliable availability of nutritious food and the inability to consistently obtain food without resorting to socially unacceptable practices."2 More than 14% of people living in the U.S. are food insecure. This rate is higher among African Americans, Latinos, low-income households, and households with single mothers. The risk of diabetes is doubled in those who are food insecure.

Diabetes is also more common among non-English speaking people in the U.S. Homelessness is another concern, as it often accompanies many of the barriers to adequate diabetes management including food insecurity, literacy and numeracy deficits, lack of insurance, cognitive dysfunction, and mental illness.2

Although significant evidence indicates that people with health disparities have an increased risk of developing diabetes, evidence also shows that these high-risk individuals are not being adequately targeted for screening and prevention. Efforts to screen these underserved populations should be intensified so that evidence-based treatment or prevention strategies can be initiated.

DIABETES PREVENTION PROGRAM

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) was a large prevention study of people at high risk for developing type 2 diabetes. The study's aim was to determine whether lifestyle modification or metformin could prevent or delay the development of type 2 diabetes in people who were overweight or obese with prediabetes. The 2 major goals for participants who were randomized to the lifestyle intervention group were: 1) 7% body weight loss and 2) completing a minimum of 150 minutes of physical activity per week.4 The methods used to achieve these goals were both intensive and extensive and included a structured, 16-session, one-on-one core curriculum of self-management strategies; the use of lifestyle coaches; frequent contact; supervised physical activity sessions; individualization of adherence strategies; tailoring of materials to address diversity of participants; and clinical support. The core sessions were followed by twice-monthly in-person "maintenance" sessions and telephone contact between sessions.21 Subjects who were randomized to the metformin group received 850 mg twice daily. The average follow-up was 2.8 years.

Both lifestyle intervention and metformin significantly reduced the risk of developing diabetes compared to placebo. The lifestyle interventions reduced the incidence of diabetes by 58% and metformin reduced the incidence of diabetes by 31% compared to placebo. Importantly, lifestyle intervention was significantly more effective than metformin. Subgroup analysis did show that metformin was particularly effective in patients with a body mass index (BMI) of greater than or equal to 35 kg/m² and in younger patients.4

Patients were followed after completion of the initial DPP study to see if results were sustained over time. Ten years after randomization, the positive results persisted: the incidence of diabetes was reduced by 34% in the lifestyle intervention group and by 18% in the metformin group compared with placebo.5

Other randomized controlled trials have documented similar reductions in diabetes incidence in high-risk patients. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study found a 43% relative risk reduction in the incidence of diabetes in subjects in an intensive diet and lifestyle treatment arm compared to a control group.7 The Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study also found a significant reduction in the incidence of diabetes in participants receiving diet and exercise interventions and the beneficial effects were sustained 20 years after baseline.8,9

On the basis of the results of the DPP, the ADA recommends that all patients diagnosed with prediabetes should be referred to an intensive behavioral lifestyle intervention program modeled on the DPP to achieve a 7% loss of initial body weight and increase participation in moderate-intensity physical activity to at least 150 minutes per week.2 In addition, the ADA states that metformin should be considered in patients with prediabetes, especially in patients with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher, those aged less than 60 years, women with a previous history of gestational diabetes, and those with rising A1C levels despite lifestyle intervention.2

The initial results of the DPP were published in 2002; however, the practical translation of the study into the real-world setting remains a challenge for several reasons. The DPP lifestyle intervention program was administered by highly credentialed research staff. The cost to deliver the DPP lifestyle intervention program in the first year was $1400 per participant, an expense that has been deemed too expensive to be scaled to the U.S. prediabetes population in a manner that could be sustained.22 In addition to the cost, there simply are not enough certified diabetes educators or other health care professionals to provide the DPP lifestyle intervention to the 86 million Americans with prediabetes.

Translating the DPP into practice

Significant efforts have been made to find the best way to deliver the lifestyle intervention to such a large group of Americans in a manner that effectively achieves the weight loss and activity goals using limited resources. Several studies have been published evaluating modified versions of the DPP lifestyle intervention in real-world settings. A meta-analysis of 28 such studies in the U.S. was published in 2012.23 The studies included in the analysis took place in many types of settings including community centers, recreation centers, faith-based organizations, and health care facilities. A total of 3797 participants were enrolled in lifestyle interventions and 2916 (77%) completed follow-up visits and were included in the analysis. The average weight loss 12 months after the intervention was 4%. Importantly, weight loss was similar regardless of whether the programs were administered by health care professionals or lay educators. Weight loss also increased with every additional lifestyle session attended. The authors of the meta-analysis concluded that the DPP lifestyle intervention could successfully be implemented using non-health care professionals without sacrificing effectiveness. Although 4% weight loss may not seem clinically significant, this result was similar to the weight loss achieved in the original DPP study.23

A group-based DPP lifestyle intervention through the YMCA, delivered by lifestyle coaches, was piloted in 92 participants and compared to brief counseling alone in adults who attended a screening event in a semi-urban YMCA facility. Intervention participants had more weight loss (6%) than the control group (2%) after 6 months.24 Owing to these positive findings, the YMCA partnered with United Healthcare and other organizations to expand the program, but they encountered difficulty in attracting new participants to the lifestyle intervention. An observational study of the partnership between the YMCA and an integrated medical system in Ohio showed that a concentrated, system-wide marketing and engagement effort was effective at recruiting high-risk people for the program.25

Although many initiatives emerged across the country to translate the DPP into real-world practice, a systematic, nation-wide effort did not get underway until 2010. At that time, Congress authorized the CDC to establish and lead the National DPP – a lifestyle change program for preventing type 2 diabetes that was based on the DPP study but modified in a way so that it could be used on a national scale in a manner that could be cost-effective and sustainable.12 According to the CDC, the National DPP is "a public and private initiative to offer evidence-based, cost-effective interventions in communities across the United States to prevent type 2 diabetes." The program focuses on education, dietary changes, coping skills, and group activities to help participants lose weight and engage in at least 150 minutes per week of physical activity. The program includes lifestyle coaches to give participants guidance and support. To increase the accessibility of the program and decrease costs, the lifestyle coaches must be trained but do not need to be health care professionals. The program encourages collaboration among federal agencies, community organizations, employers, insurers, health care professionals, and other stakeholders. The National DPP website (https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/index.html) offers several useful resources for screening, testing, and referring patients at risk for type 2 diabetes, including a curricular toolkit, instructions on becoming a CDC-recognized provider site, and a registry of all recognized lifestyle change programs.12

Targeting the DPP to underserved populations

Several studies have evaluated whether the DPP can be translated into effective programs targeted at underserved populations. Seidel et al aimed to evaluate whether the DPP lifestyle intervention could be successfully translated into an urban, medically underserved community.25 They targeted and screened participants from 11 neighborhoods that comprised a former hub of the steel industry that experienced downsizing in the 1980s. Increased rates of unemployment resulted in an older, socioeconomically depressed community with a high prevalence of chronic disease. Screening was offered at no cost at churches, worksites, and other community locations. Eligible subjects were invited to complete the 12-session program. In all, 573 subjects were screened and 88 subjects completed the 12-session program. A significant weight reduction was achieved in the population, with 46.4% of patients achieving at least 5% weight loss and 26.1% achieving at least 7% weight loss.26

A study by Davis-Smith et al focused on implementing a diabetes prevention program in a rural, African American church.27 The researchers developed a modified, 6-week DPP intervention, which was offered to individuals who were identified as having prediabetes during screening that was offered at the church. The researchers collaborated directly with the pastor and used focus groups of church members to guide the implementation process. The attendance rate for all 6 sessions was 78% (10 of 11 participants with impaired FPG). The program resulted in a mean weight loss of 7.9 pounds immediately after the program and a mean weight loss of 10.6 pounds 12 months after completion of the program.27

Dodani et al developed a "Fit Body and Soul" lifestyle intervention based on the DPP lifestyle intervention.28 The researchers developed a 12-week program using a faith-based approach at African American churches. The "Body and Soul" program added aspects to the DPP program to better meet the socioeconomic and cultural needs and preferences of the population. The researchers developed partnerships with the church through use of advisory boards and focus groups. Church-level interventions were led by the pastor and group sessions and individual interventions were led by community health advisors.28 Results of the intervention were not reported so it is not known whether this intervention resulted in successful weight loss or prevention of diabetes.

A study by Ruggiero et al evaluated whether a community-based diabetes prevention program could effectively reduce the risk of diabetes in an urban, underserved Latino population.29 The program focused on working with the community to tailor and enhance the program for a Latino community and was delivered by community health workers. Community health workers are "individuals who serve as bridges between their ethnic, cultural, or geographic communities and health care providers and engage their community to prevent diabetes and its complications through education, lifestyle change, self-management and social support."30 Participants were recruited during free health screenings and individuals who met prediabetes criteria participated in a community-based lifestyle intervention named "Making the Connection," which was modeled after the DPP lifestyle intervention. The researchers took a community-based approach that included regular community advisory board meetings, community forums, and inclusion of community members as project staff and interventionists. The program was also tailored to include culturally specific information on diabetes risk and culturally relevant and language-appropriate education materials. The researchers were purposeful in their efforts to minimize barriers such as literacy and education levels, language, income, transportation, and lack of insurance. Results showed that this approach to reach this underserved population by delivering the program in the community in collaboration with community health workers led to improvements in both anthropometrics and behavioral outcomes.29

Other programs designed to reduce disparities

Every decade, the Healthy People Initiative develops a set of objectives to improve the health of all Americans. One Healthy People 2020 goal is to reduce the disease burden of diabetes and improve the quality of life for all persons who have, or are at risk for, diabetes. The initiative identifies that, to meet this goal, "health care professionals must recognize the impact that social determinants have on health outcomes of specific populations and be aware of the disparities they create."30 Therefore, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion has partnered with the National Center for Health Statistics and the Office of Minority Health to expand the Healthy People data search function to include a tool that shows health disparities information. The disparities search function tool is known as DATA2020 and can provide health care professionals with useful statistics related to health disparities.31

The Alliance to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes aims to use evidence-based, innovative practices to help reduce diabetes disparities and inequalities among underserved populations. It is focused on priority populations including African Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians. The Alliance has developed and implemented evidence-based diabetes programs for low-income and underserved populations using multi-component approaches that take into account cultural norms, community characteristics, and health care system challenges.32

The Alliance model consists of 3 core elements: "(a) institutionalizing patient self-management education in targeted health facilities, (b) institutionalizing cultural awareness education for providers, and (c) modifying existing service delivery policies and procedures (or initiating new ones) to support provision of high-quality clinical care and enhanced clinician–patient communication."33

ROLE OF THE PHARMACIST

Pharmacists make up a significant proportion of certified diabetes educators and need to have improved awareness of diabetes risk and prevalence among underserved populations. However, the number of certified diabetes educators in the U.S. is just over 17,000 – a miniscule number compared to the number of people with prediabetes and those at future risk for developing diabetes or prediabetes. Therefore, all health care professionals, including pharmacists, must have improved awareness of diabetes risk and must be able to identify and educate patients who are at risk. In addition, pharmacists should routinely educate and support all patients about healthy eating to maintain a healthy weight in those who are not overweight or to lose weight in those who are overweight or obese. Pharmacists should be aware of the key features of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and should be familiar with the "Choose My Plate" educational tools that are available.34 Key messages of the dietary guidelines include: everything a person eats and drinks matters – focus on variety, amount, and nutrition; choose foods and beverages with less saturated fat and added sugars; make half of the plate vegetables; and start with small changes. Educational information and online tracking tools are available at www.ChooseMyPlate.gov.

Awareness is crucial in the effort to stop type 2 diabetes, and knowing that a person has prediabetes is just the first step in preventing the onset of type 2 diabetes. Pharmacists can help their patients prevent diabetes by offering routine, free diabetes screening events and can make efforts to partner with community champions to specifically target underserved populations in their geographic areas. Pharmacists should especially consider those at highest risk for diabetes, including high-risk ethnic groups, those who are food insecure, non-English speaking individuals, and those who are homeless. Educational programs and materials must be developed in multiple languages and at appropriate literacy levels.

In addition to screening all patients for diabetes, pharmacists can identify high-risk patients and patients with prediabetes and refer them to a CDC-recognized diabetes prevention lifestyle change program. Referring patients to a CDC-recognized diabetes prevention lifestyle change program is smart practice: research shows that patients are more likely to engage in preventive health behaviors if their health care professionals recommend them.

CDC-recognized lifestyle change programs are available in health care clinics, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, pharmacies, wellness centers, worksites, cooperative extension offices, university-based continuing education programs, and other locations throughout communities. Patients can also choose an online program. Many employers and insurers offer the lifestyle change program as a covered benefit. Patients should check with their insurer or employer to see if the program is covered. Pharmacists can help patients find a program that will work for them. A registry of all recognized lifestyle change programs can be found on the CDC National DPP website at https://nccd.cdc.gov/DDT_DPRP/Registry.aspx.12

For patients who have prediabetes, pharmacists can also provide education and reinforcement similar to what was offered in the DPP lifestyle intervention. Educational efforts should focus on reducing total dietary (calorie) intake, reducing total and saturated fat intakes, and increasing leisure time physical activity. Pharmacists can educate patients to increase intake of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; reduce portion sizes; and decrease intake of sweetened beverages. Education on behavior changes and self-management strategies – including monitoring – using diet and exercise logs to assist behavior change are also effective.

Education and outreach programs should be designed to overcome the specific barriers faced by underserved populations. To be successful, education and outreach programs need to incorporate community champions and consider the unique barriers and health care needs of particular underserved patient populations. Education and screening programs need to be tailored to cultural and specific needs of the population in order to be successful. The ADA recommendations state that, to reduce disparities, providers should assess social context, including potential food insecurity, housing stability, and financial barriers, and apply that information to treatment decisions. Patients should be referred to local community resources when available and patients should be provided with self-management support from lay coaches or community health workers when available. Structured programs that are developed should integrate culture, language, finance, religion, and literacy and numeracy skills.2

The National DPP website offers several useful resources for screening, testing, and referring patients at risk for type 2 diabetes. The entire toolkit, as well as individual components, is easily accessible for download at https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/pdf/STAT_Toolkit.pdf.

Pharmacists may also apply to host a CDC-recognized diabetes prevention program. Requirements and the detailed curriculum are also available, along with a lifestyle coach training guide and patient handouts in both English and Spanish, at https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/lifestyle-program/curriculum.html. The curriculum includes 26 modules. In order for a program to receive CDC recognition, it must complete at least 22 modules. A detailed list of the curriculum modules is provided in Table 3.11

| Table 3: National Diabetes Prevention Program Curriculum: "Prevent T2" Modules11 |

| First 6 months of the program (must complete all 16 modules) |

| Module title |

Description |

| Introduction to the Program |

Sets the stage for the entire program |

| Get Active to Prevent T2 |

Core principles of getting active |

| Track Your Activity |

Core principles of tracking activity |

| Eat Well to Prevent T2 |

Core principles of healthy eating |

| Track Your Food |

Core principles of tracking food |

| Get More Active |

Core principles of increasing activity level |

| Burn More Calories Than You Take In |

Core principles of caloric balance |

| Shop and Cook to Prevent T2 |

Teaches participants how to buy and cook healthy food |

| Manage Stress |

Teaches participants how to reduce and deal with stress |

| Find Time for Fitness |

Teaches participants how to find time to be active |

| Cope with Triggers |

Teaches participants how to cope with triggers of unhealthy behaviors |

| Keep Your Heart Healthy |

Teaches participants how to keep their heart healthy |

| Take Charge of Your Thoughts |

Teaches participants how to replace harmful thoughts with helpful thoughts |

| Get Support |

Teaches participants how to get support for their healthy lifestyle |

| Eat Well Away from Home |

Teaches participants how to stay on track with their eating goals at restaurants and social events |

| Stay Motivated to Prevent T2 |

Helps participants reflect on their progress and keep making positive changes over the next 6 months |

| Second 6 months of the program (must complete at least 6 of the 10 modules) |

| Module title |

Description |

| When Weight Loss Stalls |

Teaches participants how to start losing weight again when their weight loss slows down or stops |

| Take a Fitness Break |

Teaches participants how to overcome barriers to taking a 2-minute fitness break every 30 minutes |

| Stay Active to Prevent T2 |

Teaches participants how to cope with some challenges of staying active |

| Stay Active Away from Home |

Teaches participants how to stay on track with their fitness goals when they travel for work or pleasure |

| More About T2 |

Gives participants a deeper understanding of type 2 diabetes |

| More About Carbs |

Gives participants a deeper understanding of carbohydrates |

| Have Healthy Food You Enjoy |

Teaches participants how to have healthy foods that they enjoy |

| Get Enough Sleep |

Teaches participants how to cope with the challenges of getting enough sleep |

| Get Back on Track |

Teaches participants what to do when they get off track with their eating or fitness goals |

| Prevent T2 – For Life! |

Helps participants reflect on their progress and keep making positive changes over the long term |

Pharmacists with diabetes education training or experience could also be responsible for training lay educators to administer the lifestyle intervention program. On the basis of results of the meta-analysis of DPP translational studies, training should be focused on minimum core competencies (basic knowledge, organizations skills, and empathy).23

Finally, pharmacists can recommend metformin as a reasonable medication option in patients with prediabetes, particularly in patients with a BMI higher than 35 kg/m², those aged 60 years or younger, women with prior gestational diabetes, or those with rising A1C levels despite lifestyle intervention.2

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes remains high, and disparities exist in the screening and management and the disease. Therefore, it is critical for pharmacists to engage in activities that target these disparities in the screening, prevention, and management of diabetes in underserved populations. Several resources are available through the National DPP and other government or national programs that can assist pharmacists in identifying and educating high-risk, underserved patients.

REFERENCES

- DeFronzo RA. Banting lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: a new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2009;58(4):773-795.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(Suppl 1):S1-S135.

- National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group; Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Goldberg R, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1677-1686.

- Lindstrom J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, et al; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): Lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3230-3236.

- Lindstrom J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1673-1679.

- Pan XR, Li G, Hu Y, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(4):537-544.

- Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371(9626):1783-1789.

- Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837-853.

- Diabetes Report Card 2014. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/library/diabetesreportcard2014.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed July 17, 2017.

- National Diabetes Prevention Program. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/index.html. Updated June 22, 2017. Accessed July 17, 2017.

- Geiss LS, Wang J, Cheng YJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence trends for diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 20 to 79 years, United States, 1980–2012. JAMA. 2014;312(12):1218-1226.

- About Diabetes Disparities. Alliance to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes. http://ardd.sph.umich.edu/about_diabetes_disparities.html. Published 2011. Accessed July 9, 2017.

- The Secretary's Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. Phase I Report: Recommendations for the Framework and Format of Healthy People 2020. http://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/PhaseI_0.pdf. Published October 28, 2008. Accessed July 17, 2017.

- Selected Social Characteristics in the United States. American FactFinder; U.S. Census Bureau. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_08_1YR_CP2&prodType=table. Accessed July 17, 2017.

- Starke Casagrande S, Cowie CC, Genuth SM. Self-reported prevalence of diabetes screening in the U.S., 2005-2010. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):780-787.

- Tung EL, Baig AA, Huang ES, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes screening between Asian Americans and other adults: BRFSS 2012-2014. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):423-429.

- Osborn DP, Wright CA, Levy G, et al. Relative risk of diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension and the metabolic syndrome in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:84.

- Mangurian C, Newcomer JW, Vittinghoff E, et al. Diabetes screening among underserved adults with severe mental illness who take antipsychotic medications. JAMA Internal Med. 2015;175(12):1977-1979.

- Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2165-2171.

- Herman WH, Brandle M, Zhang P, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Costs associated with the primary prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(1):36-47.

- Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(1):67-75.

- Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(4):357-363.

- Adams R, Hebert CJ, McVey L, Williams R. Implementation of the YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program throughout an integrated health system: a translational study. Perm J. 2016;20(4):82-86.

- Seidel MC, Powell RO, Zgibor JC, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into an urban medically underserved community: a nonrandomized prospective intervention study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):684-689.

- Davis-Smith YM, Boltri JM, Seale JP, et al. Implementing a diabetes prevention program in a rural African-American church. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(4):440-446.

- Dodani S, Kramer MK, Williams L, et al. Fit body and soul: a church-based behavioral lifestyle program for diabetes prevention in African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):135-141.

- Ruggiero L, Oros S, Choi YK. Community-based translation of the diabetes prevention program's lifestyle intervention in an underserved Latino population. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(4):564-572.

- American Association of Diabetes Educators. AADE Position Statement: Community health workers in diabetes management and prevention. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(3):48S-52S.

- Healthy People 2020. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/HP2020_brochure_with_LHI_508_FNL.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed July 17, 2017.

- Goode TD, Jack L. The alliance to reduce disparities in diabetes: infusing policy and system change with local experience. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(2 Suppl):6S-10S.

- Clark NM, Brenner J, Johnson P, et al. Reducing disparities in diabetes: the alliance model for health care improvements. Diabetes Spectrum. 2011;24(4):226-230.

- 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th edition. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Published December 2015. Accessed August 16, 2017.

Back to Top