Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Module 6. Staying Alert for Insulin Safety: Promoting Safe Practices to Protect Patients

Introduction

Insulin is a hormone that is produced by the pancreas that allows cells in the body to take in the energy they need to function properly. Since the discovery of insulin in the 1920's, insulin therapy has changed in many ways. Today, patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rely on insulin replacement as the mainstay of therapy. It is also commonplace for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) to use insulin as part of their treatment regimens. It is estimated that 6 million Americans use insulin, with 14% using insulin alone and 14.7% taking oral medications with insulin.1

Insulin is designated by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) as a high-alert medication that is associated with high risk of injury when used in error.2 Errors made in insulin dosing and/or injection technique can lead to severe consequences for patients.3 It has been associated with more medication errors than other classes of drugs.4 In 2008, insulin represented 16% of all medication error events and a 2010 study revealed that it was the most common medical error in critical care patients.2

Most importantly, insulin errors can lead to severe hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, which can be fatal.5 Practitioners must, therefore, pay particular attention to patient education about insulin products and ensure that patients thoroughly understand the use of this medication and are comfortable with appropriate administration of recommended doses. Many patients in hospitals require insulin making safety concerns prominent in this patient population as well. Pharmacy technicians should be aware of potential risks that can occur in hospitals or the community setting and the need for protocols and safe practices that can be used to reduce the chance that insulin errors can occur.

Insulin Overview

When a patient uses insulin, it is important that they understand how often and how much insulin to use. Insulin is measured in units, and an insulin pen or a dedicated syringe for insulin delivery with unit markings is the only way injectable insulin should be administered. Patients must also understand what type of insulin they will be using, and how each variety of insulin works. For patients with T2DM, some practitioners initiate insulin therapy with a once-daily basal insulin regimen.6 Basal insulin is a long-acting insulin product that releases small amounts of "background" insulin over time. In normal physiology, the pancreas continuously secretes small amounts of insulin to help the body maintain a basal metabolic rate. Exogenous basal insulin regimens attempt to mimic this normal process. There are several long-acting insulin options and the main differences among the products are the durations of action. The durations of basal insulins range from 12 to 72 hours, and some of the newer basal insulins in development may have even longer durations. The starting dose of basal insulin for a patient with T2DM is often 10 to 20 units of a basal insulin given at bedtime, but all insulin regimens are unique and adjusted to meet the needs of each individual patient. Doses for basal insulin are usually based on weight.6 Timing of the injections can vary from morning to afternoon or evening, but patients must be educated that whatever time they decide to administer their basal insulin injections, they should do so at the same time every day. This maintains consistent insulin absorption and allows effective steady state peaks of insulin.7 Long-acting basal insulin products available include insulin glargine, degludec, and detemir. These products have durations of approximately 24 hours in most patients and they release insulin slowly throughout the day.

Insulins with intermediate durations of action can also be used to replicate basal insulin secretion. NPH insulin (Novolin N, Humulin N) lasts approximately 8 to 10 hours. The activity of intermediate-acting insulin peaks approximately 6 to 8 hours after injection, which, under some circumstances, provides coverage for meals consumed around that time. Patients should try to eat close to the time of the insulin peak or risk having low blood sugar. NPH insulin is a cloudy suspension, not a clear solution like other types of insulin, and NPH needs to be mixed or rolled (not shaken) before use. NPH insulin is also available in pre-mixed vials and pen devices in which NPH insulin is combined with regular human insulin (a shorter-acting product). The pre-mixed insulin is usually administered twice daily because of the duration of action of the NPH insulin.8

Another component of insulin therapy is bolus insulin. Normally, the pancreas responds to a glucose load (e.g., an intake of glucose or its precursors during a meal) by secreting insulin. Exogenous bolus doses of insulin are administered to mimic this physiological process of "covering" a meal. Some patients with T2DM use bolus insulin, but all patients with T1DM require it, in addition to basal therapy. If a patient is using different types of insulin, it is important to emphasize that he or she must always double check the dose and type of insulin used prior to injection. Currently available injectable mealtime insulins for bolus dosing include insulin aspart (Novolog, Fiasp), glulisine (Apidra), lispro (Humalog), and regular human insulin (Humulin R). Insulins aspart, glulisine, and lispro begin to work within approximately 15 minutes after injection; regular human insulin is used less frequently because it takes up to 30 minutes to take effect. Because patients are often instructed to inject regular insulin 30 minutes before they eat, this particular mealtime insulin carries an increased risk for hypoglycemia if the patient becomes distracted and forgets to consume a meal after injecting the insulin. Doses of mealtime insulins will depend on a patient's insulin sensitivity and how many grams of carbohydrate they consume at a given meal.

Bolus insulin preparations are meant to be used to cover meals or food intake. These insulin products are generally administered before or with a meal, depending on a patient's blood sugar levels. Because these are short-acting and rapid-acting insulin products, it is imperative that patients know they are only to be administered with meals. Insulin therapy can be confusing, especially to new users, so patient education is a significant factor in guaranteeing that patients with diabetes stay healthy and safe. Pharmacy technicians can assist patients with diabetes by asking open-ended questions to assess how well a patient understands his or her therapy.9

Hypoglycemia: Patient Risk during Hospitalization and at home

Many safety concerns surrounding insulin use involve preventing hypoglycemia in patients. Hypoglycemia is a serious risk with insulin therapy that can result in patient harm and greater healthcare utilization. One study found there were nearly 100,000 visits for insulin-related hypoglycemia annually.2 Of these patients, one-third resulted in hospitalization.2 Symptoms can include shakiness, irritability, confusion, tachycardia, and hunger.10 Hypoglycemia can progress to loss of consciousness, seizure, coma, or death if it is unrecognized and falls, motor vehicle accidents, or other injury can occur.10

For hospitalized patients, risk of hypoglycemia is increased by kidney and liver failure, variable caloric intake, recovery from illness, de-escalation of corticosteroids, age, and increased physical activity from rehabilitation.11 Patients who have experienced hypoglycemic episodes are more likely to have repeat episodes, with one study showing a prior episode in 84% of patients with severe hypoglycemia.12 Timing of caloric intake, insulin administration, and glucose monitoring can impact glucose levels. Misalignment of these actions has been cited as a contributor to hypoglycemia.2 Complications of hypoglycemia include cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and patient-fall events which can result in longer hospital stays, higher costs, greater risk of discharge to skilled nursing facilities rather than home, and increased mortality.2,12

The risk of hypoglycemia can be a source of anxiety for many patients with diabetes. It is recommended by ADA guidelines that “Individuals at risk for hypoglycemia should be asked about symptomatic and asymptomatic hypoglycemia at each encounter”.10 Pharmacy technicians can play a role in care by asking patients about their experiences with hypoglycemia. Frequent episodes may require changes to medication or insulin regimens and evaluation of glucose targets. Some patient may need a higher target range to avoid low blood glucose.10 Appropriate management includes 15-20 grams of glucose or use of glucagon for significant hypoglycemia. Patients treated with insulin should receive education on signs of hypoglycemia and should be referred to a pharmacist for information on being prepared for hypoglycemic events.

Hospital Insulin Safety

Safe use of insulin is an important concern in hospital or health-system settings. Between 25%-30% of hospitalized patients have diabetes and another 5%-10% will be diagnosed during their stay.11 In the hospital, patients are predisposed to hyperglycemia (high blood glucose) due to factors such as steroid use and infection.11 Stress of illness can result in relative low amounts of insulin which can trigger immune dysfunction, oxidative stress, and impaired healing in patients.13 Many patients do not receive suitable glycemic therapy (i.e., insulin or other medication for diabetes) during hospitalization and often have changes in their diet and exercise routines.2,11,13 Consequences of high blood glucose in hospitalized patients include slower wound healing, risk of infection, delays in surgery, delays in discharge, decreased neurologic recovery, cardiovascular events such as heart attack, and death.12,13 Hypoglycemia (low blood glucose), often from insulin misuse, is also problematic in hospitals.14

Common errors with insulin that can occur in the hospital include administration of the wrong product, skipping a dose, using an incorrect delivery devices, wrong route, and improper patient monitoring.2 Improper dosing where patients receive too much or too little insulin can results in glucose outside the normal range.2 Factors contributing to insulin errors reported from nurses, physicians, and pharmacists include lack of documentation, lack of training, transition from intravenous (IV) to subcutaneous insulin, availability of multiple products, and unclear prescriptions.14 Lack of nutritional status information such as if a patient is NPO (nothing by mouth) or has a restricted diet can lead to patient harm if insulin doses are not adjusted to the patient’s diet.14 Nutritional status can change throughout a hospital stay, creating the need to communicate this information frequently for diabetic patients. Also, delays between blood glucose measurement and insulin dosing can cause incorrect amounts of insulin to be administered, leading to hyper-or hypoglycemia. This is also possible if meals are not coordinated with glucose testing and insulin administration appropriately.2,14

To help avoid errors and risks that exist with insulin, several specific categories of risk associated with subcutaneous insulin use that have been overlooked and inadequately addressed have been identified by the ISMP.2

| Figure 1. Areas of Risk Associated with Insulin |

- Errors and poor outcomes with sliding scale insulin dosing

- Variable or absent insulin standard order sets

- Intermediate and long-acting subcutaneous insulin doses not dispensed in the most ready-to-use form in inpatient settings

- Errors with communicating and measuring doses of CONCENTRATED INSULIN

- Poor coordination of insulin with meals and glucose monitoring in inpatient settings

- Lack of protocols to guide insulin administration

- Lack of prospective risk assessment to identify patients at high risk for hypoglycemia

- Lack of prospective risk assessment to identify patients at high risk for hyperglycemia

|

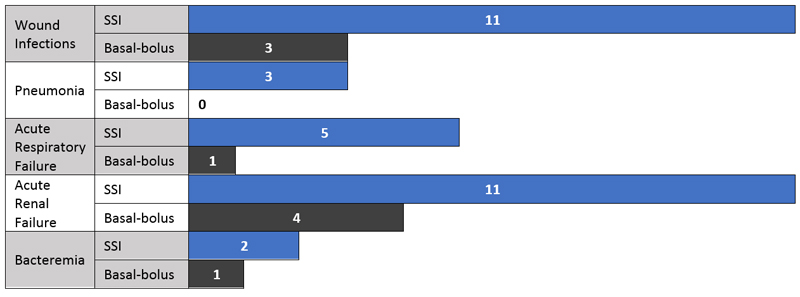

ISMP guidelines include “Eliminate the use of sliding scale insulin doses based on blood glucose values as the only strategy for managing hyperglycemia.”2 In the past, sliding scale insulin (SSI) was the standard method for prescribing insulin in the hospital. This system bases the insulin dose, usually regular insulin, on the patient’s blood glucose level. Now, SSI protocols alone are no longer recommended.12 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) recommendations for safe insulin use advocate the need to “eliminate the routine administration of correction/sliding scale insulin doses as a primary strategy to treat hyperglycemia.”15 Evidence supports that SSI may not be the best way to control blood glucose in hospitalized patients and it may lead to harmful hypoglycemia.11,12 Basal-bolus (long-acting insulin with bolus insulin for meals and corrections) regimens are now preferred for patients who are not critically ill.10,13,15 When compared to patients receiving basal-bolus insulin, one study found that SSI patients had more complications (see Figure 2).13 SSI orders were often free form and specific to each provider, leaving room for misinterpretation and errors.4

Figure 2. Hospital Complications: SSI vs. Basal-bolus16

Another recommendation is that “insulin orders are free of error-prone abbreviations and dose expressions.” For example, “units” should be used instead of “u” or “IU” and subcutaneously should be abbreviated “subcut.” "U" is often misinterpreted as a "0." Also, the order "6 IU" can be misinterpreted as 61 units instead of 6 units. In this example, the unit of measurement is also incorrect: "international units" are not used to measure insulin.

Use of tall man lettering with bolded text should be used to help distinguish look-alike insulin names (e.g., HumaLOG and HumuLIN; NovoLOG and NovoLIN).2 Errors can easily occur if orders are not interpreted correctly, so all health care professionals involved in the medication use process must read all orders carefully and have multiple checks in place to verify the accuracy of all insulin products prescribed and administered. Storing different types of insulin in ways that help avoid confusion is also highlighted. Storage in separate, labeled bins and use of auxiliary labels and barcode technology can assist with correct drug selection and validation.2 Another practice to help avoid mix-ups is to remove vials from the manufacturer’s carton so that vials are not returned to the wrong carton. Basal insulin should be avoided in patient care areas and only dispensed from the pharmacy to avoid confusion with rapid-acting insulin.2 Care should be used with "sound-alike" insulin products, such as Novolin/Novolog and Humulin/Humalog. These medications can be easily confused with each other. In the hospital setting, there have also been reports of fatalities due to heparin and insulin mix-ups.

Many organizations recognize that transitions through the healthcare system and to home need special attention.2,10,15,17 Difficulties in sharing information among clinicians and risks of glucose fluctuations for patients at these points are problematic. However, transitions can give healthcare workers the opportunity for assessment and therapeutic adjustments for patinets.17 One important and often confusing example is the transition from IV to subcutaneous insulin as patients move away from intensive care and may have changes in nutritional status.12 The ADA promotes use of protocols when discontinuing IV insulin and suggests that subcutaneous basal insulin, converted to 60%-80% of the daily infusion dose, be initiated 2 to 4 hours before IV insulin is discontinued.10 Communication by all members of the healthcare team is important to ensure patient safety in the health-system and beyond.

Insulin Pen Safety: Challenges for Hospitals and Home Use

Newer insulin products are emerging in pen devices with unique durations and concentrations (e.g., insulin degludec, insulin degludec/insulin aspart 70/30, insulin glargine U-300, regular human insulin U-500).18 These products offer benefits such as accuracy, convenience, labeling and barcoding, reduced time requirements, reduced waste, and ease of use.2 Unfortunately, errors in hospitals related to using the pen incorrectly, using the pen as a multi-dose vial, and using one pen for multiple patients have led to dosing errors and bloodborne pathogen exposure.2 The FDA has received notifications of thousands of patients possibly exposed to infections that are transmitted through blood through sharing of multi-dose pen devices.19 As a result, the ISMP has targeted insulin pens as an area for improvement.2 Their suggestions include:

- Ideally, insulin pens are dispensed to the clinical units with a patient-specific, barcode label (that has been applied in the pharmacy, using a barcode verification process that confirms the correct pen type has been selected based on the patient’s order) AND steps have been taken to ensure that only the correct patient-specific label can be scanned at the bedside.

- A patient-specific label is affixed on the body of the insulin pen (not on the removable cap), without obscuring important information on manufacturer labeling or the dose counter/dose window.

Proper technique is necessary when patients are using pen dosing-devices in the hospital or at home. Several potential medication errors exist with insulin pens that can lead to harmful effects for the patient such as infection, dose inaccuracy. 20,21 If patients do not receive the correct dose of insulin, the result can be hypoglycemia or uncontrolled HbA1c.20,21 Proper technique and storage of devices in important in achieving glycemic control.22

Instructions from the manufacturer may explain how to perform injections correctly but may not explain why each step is necessary. When given the rationale behind each action, more patients are likely to adhere to recommended steps, such as pen priming. Clinicians need to be involved in instructing patients on the use of pen dosing devices so that they may explain to patients why each step is important and be able to answer questions that may arise.22 Technicians can question patients about injection technique and pen needle use so that they may refer patients to the pharmacist for education.

Some products are available as the more traditional U-100 as well as a different concentration (i.e., U-200, U-300, U-500; see below). This along with multiple products that have the same strength (e.g., insulin degludec/insulin aspart 70/30 and human insulin isophane/human insulin 70/30) can lead to confusion when changing therapy.23 For patients who may have used pen devices in the past, errors may occur due to manufacturer-specific differences such as storage requirements, time to expiration, and duration of time that needles should be left in the skin after injection. Education is necessary to clarify these areas when patients begin using a new device.

Concentrated Insulin

Varying concentrations of insulin that are available can be a source of confusion and a risk for errors. Most insulin is available in the concentration of 100 units/mL. This means that each mL contains 100 units of insulin. Now, U-500 regular insulin, U-300 glargine, U-200 degludec, and U-200 lispro also exist.24 Steps must be taken to ensure the correct concentration of insulin is used and the correct dose is given. In 2016, the US FDA approved a newly designed syringe purposed for use with U-500 regular insulin to directly measure proper doses without the need for a conversion.24 Pen forms of concentrated insulin do not require conversion and can assist patients with delivering the appropriate amount of insulin. However, awareness and safety measures are still necessary.

In the hospital, concentrated insulin not supplied in pens is recommended to be overseen by the pharmacy to avoid dosing errors.2 Other ISMP recommendations include:

- U-500 insulin is dispensed in patient-specific, labeled pen devices or in patient-specific, pharmacy-prepared U-500 syringes.

- U-500 insulin vials and syringes are only stored in the pharmacy. Other concentrated insulins (e.g., U-200 and U-300) are dispensed in patient-specific, labeled pen devices.

Insulin Patient Education and Training

Insulin is principally available as an injectable product. Inhaled insulin is also available. As such, insulin requires more attention to patient education than most oral medications. Many patients are concerned and fearful about starting insulin therapy; these apprehensions may stem from discomfort with needles, expectations of pain, or anxiety about the complexity of a new daily regimen. Proper education helps to allay these fears. It is, therefore, incumbent on the entire health care team to ensure that a patient has a thorough understanding of how to safely store and inject insulin and properly dispose of needles.

INJECTING INSULIN: KEY POINTS FOR PATIENTS

A patient using insulin must be comfortable measuring and drawing up the proper doses of insulin. Many patients now use insulin pens, which makes insulin injections easier and simpler than in the past.25 Patients with manual dexterity issues or vision problems will likely find that an insulin pen is easier to use than vials and syringes. Because training patients on pen injection technique has been shown to improve HbA1C, fasting plasma glucose, and overall glycemic control, pharmacists should understand the consequences of improper injection technique with pens and the importance of talking to patients about pen use.26,27

On a pen, a dose is "dialed up" using a dosage dial generally found at the base of the pen device. Patients must know how to read the dose through the dosing window of the device. Proper technique includes use of a new pen needle with each injection, priming the pen after needle attachment, holding for the specified time prior to withdrawal of the needle from the skin, rotation of injection sites, storing in-use pens at room temperature without a pen needle attached, and discarding pens after manufacturer-specified days of use.22 Omitting any of these steps can lead to problems with drug delivery. Other errors that have been identified include injecting through clothing, dialing to zero rather than depressing the injection button, withdrawing insulin from the pen/using pens as vials, and using pens for more than one patient.28,29,30

There are, however, still patients who use vials of insulin and need to draw up doses using a syringe. Several important safety tips will keep patients safe and comfortable with insulin therapy:

- The patient must verify and understand the dose to be administered. Insulin is measured in units and an insulin syringe should always be used when drawing up an insulin dose from a vial.

- Insulin syringes are available as 3/10 ml, ½ ml, and 1 ml sizes. The best way to determine if a patient is using the correct syringe size is to evaluate the dose of insulin. If the insulin dose is 30 units or less, the 3/10-ml syringe is best; if the insulin dose is between 31 and 50 units, the ½-ml size is best; and the 1-ml syringe should be used for doses higher than 50 units.

- Current recommendations for needle size have been evaluated in several studies, and it has been found that short needles (4 mm in length) are best for most patients. This size makes it easy for patients to inject only into the subcutaneous tissue and to avoid injecting into muscle.31Lean patients may require shorter needles.

- Avoid sharing or reusing syringes. Sharing and reusing needles increases the risk of infection.2

- If a patient is using two types of insulin in the same syringe, he or she must always draw up the shorter-acting insulin into the syringe first. This is not a frequent practice, since pre-mixed insulins containing an intermediate-acting and a rapid-acting insulin (e.g., Novolog 70/30, Humulin 70/30) are readily available. Patients may mix insulin if they use NPH and regular insulin together.

- Before injecting NPH or intermediate-acting insulin products, patients must roll the vial between the palms a few times, or, in the case of a pre-filled pen, rock it gently back and forth. This will ensure that the concentration of the product is uniform before injection. Never shake insulin products.

- To avoid insulin leaking out at the injection site, patients can count to 10 after injecting insulin before withdrawing the needle.

INSULIN INJECTION SITES

In addition to understanding how to measure the dose, patients must know how and where to inject insulin safely and effectively. If proper injection technique is not followed, inaccurate insulin dosing can occur due to poor absorption of insulin.32 This can lead to erratic blood sugar levels and even hospitalization in some extreme instances.

Insulin is self-administered as a subcutaneous injection, which means it is injected just under the skin. (In hospital settings, regular insulin may be administered intravenously.) Subcutaneous administration is best accomplished by gently pinching a piece of skin (such as under the arm or on the side of the thigh) and injecting the insulin. This avoids injecting into the muscle. However, with short needles (e.g., 4 mm in length), patients can often inject at a 90-degree angle without pinching the skin.

There are three sites that are commonly used for insulin injections: the arm, the abdomen, and the thigh. The buttocks can also be used, but a caregiver would be more likely to use this area as an injection site. Some people prefer using the abdomen for insulin injections because there is usually extra skin available and it is easy to visualize the injection site. Studies have shown that different injection areas allow different rates of insulin absorption, and the abdomen has the fastest absorption rate.33 This information may be helpful when a patient has concerns about fluctuating blood sugar levels after varying injection sites.

Patients should avoid injecting insulin close to the belly button or near moles or scars. Injecting insulin in locations such as these can lead to ineffective absorption of insulin.34 Areas that contain a lot of blood vessels, such as the inner thighs, should also be avoided, because injecting in such sites can cause pain and possible bleeding. Patients should also avoid injecting in an area that they will be exercising, such as the arm, if they will be playing golf or tennis shortly after the injection. Exercise may cause insulin to be absorbed too rapidly.33

As discussed with insulin pen use, it is important to stress to patients that they should rotate injection sites regularly and use new needles with each injection to avoid issues such as tissue irritation, erratic absorption of insulin, and infections.33 Lipohypertrophy is a consequence that can result from poor injection practices that has been associated with hypoglycemia, glycemic variability, and increased costs.28 Lipohypertrophy is the development of thickened, “rubbery” lesion in the subcutaneous tissue after multiple injections in the same site that can lead to impaired insulin absorption.28 It may be helpful for patients to keep a journal or diary to keep track of where they are injecting. This may be especially important for older patients with memory issues.

INSULIN STORAGE

Also, improper storage and use beyond the expiration date can compromise the potency and therefore the effectiveness of the drug. Insulin that is not being used should be stored in the refrigerator. Any insulin vials that are "in use" can be stored outside of the refrigerator for approximately 1 month. (Always check manufacturer product inserts for exact storage requirements.) Most insulin pens can be stored outside of the refrigerator for 7 to 28 days. Insulin that is cold can produce a more painful injection than room-temperature insulin.33

Avoid exposing insulin products to extreme heat or cold. Insulin is a protein, and this makes it subject to degradation or breakdown in extreme temperatures.33 Suggest that patients traveling with insulin use insulated travel bags with an ice pack to keep the insulin from getting too hot. Conversely, if cold weather is a factor, it is important to keep insulin products from freezing. Additionally, keep insulin products away from direct sunlight; this can also cause a breakdown of the protein. Any time a patient questions the effectiveness of his or her insulin, ask him or her how the insulin is stored and carried.

PROPER NEEDLE DISPOSAL

In a single year, approximately 9 million syringe users administer more than 3 billion injections outside traditional health care facilities. Nearly two-thirds of these people who self-administer insulin at home have diabetes. Patients may not be aware of safe disposal methods for used needles and syringes and they may simply throw the used needles in the trash or flush them down the toilet. This practice poses a serious risk of injury and infection to anyone who encounters the used products and devices.35

Help patients and caregivers identify a sharps disposal container that they can use. Red "sharps containers" are usually sold in pharmacies. This is the best option for needle disposal, but patients may be unwilling to incur the added expense of a regulation sharps container. Additionally, patients may believe that throwing a needle in the regular trash is safe. In many cases, sharps are disposed of improperly because patients are not provided any guidance by their health care team on proper needle disposal. In 2004, the Environmental Protection Agency, in a collaborative effort with the Coalition for Safe Needle Disposal, published a set of guidelines for proper needle disposal outside of a hospital or health facility setting. The guidelines emphasized the importance of not disposing of sharps directly in the household trash.35

If a patient has no access to a red sharps container, a heavy-duty plastic container such as a laundry detergent bottle may suffice.36 State and local agencies have different laws and requirements for how to dispose of these improvised sharps containers. Refer patients to the local health department for additional information.

INSULIN WITHOUT A PRESCRIPTION

Several insulin products can be purchased without a prescription: regular insulin (Novolin R, Humulin R), NPH insulin (Novolin N, Humulin N), and combination products (Novolin 70/30, Humulin 70/30). These products can be sold in vials, but they are not available in pen devices without a prescription. This improves access to insulin for patients with diabetes, but it also presents problems for patients who do not understand how to effectively and safely use insulin.

Patients who purchase insulin without a prescription may not necessarily understand what type of insulin they need and how much to use. A patient may have stopped taking insulin and decided to restart it on his or her own, without medical supervision. Patients from other countries who purchase insulin in the United States may not understand how insulin products differ from each other and from those available in other countries. Some people even "share" insulin, believing it is safe to treat themselves and others. It is an ongoing debate among health care professionals whether insulin should be available without a prescription, since insulin can cause serious health problems if used incorrectly and without proper supervision by a health care professional. Medication errors can happen when patients change from a long-acting insulin to a short-acting insulin purchased over-the-counter. Dangerously low blood sugars can result from such an error and cause serious, even fatal, consequences.37

Insulin syringes are, of course, a necessary component of injectable insulin therapy. Although many states do not require a prescription for syringes, some states still do, and other states have limits on quantities that can be purchased without a prescription. Some states have age restrictions for purchasing syringes, and some states require the purchaser to disclose the intended use for the syringe. Check with state regulatory agencies to confirm requirements for selling insulin syringes.

CONCLUSION

The use of insulin requires patient and healthcare providers to use care with doses, measurements, injection techniques, and storage conditions. Pharmacy technicians are often the first point of contact for diabetic patients in a busy pharmacy and are involved with insulin use at many steps in the inpatient environment. Pharmacy technician can promote insulin safety by using practices recommended to reduce potential errors and being aware of common error that may occur. In the community, technicians can open conversations with patient to help pharmacists identify those at risk for insulin errors. If a patient is not sure how to use or inject insulin, the technician can alert a pharmacist who can provide additional counseling. Asking patients open-ended questions about their insulin therapy can ensure that they understand the proper use and administration of insulin. Examples are provided below.

| Figure 3. Patient Questions |

- How do you dispose of your insulin needles/syringes?

- How did your doctor tell you to use the medication?

- Where do you store your insulin?

- How do you store your insulin while traveling?

- Have you experienced any episodes of low blood sugar recently?

- What do you do when your blood glucose is low?

- How do you dispose of your insulin needles/syringes?

- How did your doctor tell you to use the medication?

|

References

- Fast Facts: Data and Statistics about Diabetes. American Diabetes Association DiabetesPro website. December 2015. https://professional.diabetes.org/sites/professional.diabetes.org/files /media/fast_facts_12-2015a.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2018.

- 2017 ISMP Guidelines for Optimizing Safe Subcutaneous Insulin Use in Adults. Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2017-11/ISMP138-Insulin%20Guideline-051517-2-WEB.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- High-Alert Medications in Acute Care Settings. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices website. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/high-alert-medications-acute-list. August 23, 2018. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- Harada S, Suzuki A, Nishida S, et al. Reduction of medication errors related to sliding scale insulin by the introduction of a standardized order sheet. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(3):582-585.

- Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Wang Y, et al. National trends in U.S. hospital admissions for hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia among Medicare beneficiaries, 1999 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1116-1124.

- Riddle M, Rosenstock J, Gerich J; for the Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators. The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3080-3086.

- Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger PM. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational Global Attitudes of Patients and Physicians in Insulin Therapy study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):682-689.

- Starke AA, Heinemann L, Hohmann A, Berger M. The action profiles of human NPH insulin preparations. Diabet Med. 1989;6(3):239-244.

- Insulin Basics. American Diabetes Association website. July 16, 2015. http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/treatment-and-care/medication/insulin/insulin-basics.html. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes - 2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl. 1).

- Gosmanov AR. A practical and evidence-based approach to management of inpatient diabetes in non-critically ill patients and special clinical populations. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2016;5:1-6.

- Khazai NB, Hamdy O. Inpatient diabetes management in the twenty-first century. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016;45(4):875-894.

- Kodner C, Anderson L, Pohlgeers K. Glucose management in hospitalized patients. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(10):648-654.

- Rousseau MP, Beauchesne MF, Naud AS, et al. An interprofessional qualitative study of barriers and potential solutions for the safe use of insulin in the hospital setting. Can J Diabetes. 2014;38(2):85-89.

- Cobaugh DJ, Maynard G, Cooper L, et al. Enhancing insulin-use safety in hospitals: Practical recommendations from an ASHP Foundation expert consensus panel. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(16):1404-1413.

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 surgery). Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):256-261.

- Mathioudakis N, Golden SH. A comparison of inpatient glucose management guidelines: implications for patient safety and quality. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(3):13.

- Cahn A, Miccoli R, Dardano A, Del Prato S. New forms of insulin and insulin therapies for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(8):638-652.

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires label warnings to prohibit sharing of multi-dose diabetes pen devices among patients. US Food and Drug Administration website. February 26, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm435271.htm. Accessed November 21, 2018.

- Uslan MM. Analysis: Beyond the "clicks" of dose setting in insulin pens. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2005;7(4):627-628.

- Karges B, Boehm BO, Karges W. Early hypoglycaemia after accidental intramuscular injection of insulin glargine. Diabet Med. 2005;22(10):1444-1445.

- Mitchell VD, Porter K, Beatty SJ. Administration technique and storage of disposable insulin pens reported by patients with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(5):651-658.

- Durkin M. New insulins present benefits, challenges. American College of Physicians website. Updated July 13 2016. http://www.acpinternist.org/archives/2016/07/insulin.htm?print=true. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- Johnson JL, Downes JM, Obi CK, Asante NB. Novel concentrated insulin delivery devices: Developments for safe and simple dose conversions. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(3):618-622.

- Pisano M. Overview of insulin and non-insulin delivery devices in the treatment of diabetes. P T. 2014;39(12):866-876.

- Grassi G, Scuntero P, Terpiccioni R, et al. Optimizing insulin injection technique and its effect on blood glucose control. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2014;1:145-150.

- Nakatani Y, Matsumura M, Monden T, et al. Improvement of glycemic control by re-education in insulin injection technique in patients with diabetes mellitus. Adv Ther. 2013;30(10):897-906.

- Spollett G, Edelman SV, Mehner P, et al. Improvement of insulin injection technique: Examination of current issues and recommendations. Diabetes Educ. 2016;42(4):379-394.

- Shah A, Sullivan MM, Rushakoff RJ. A new "twist" on insulin pen administration errors. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(6):617.

- Grissinger M. Avoiding problems with insulin pens in the hospital. P T. 2011;36(10):615-616.

- Gibney MA, Arce CH, Byron KJ, Hirsch LJ. Skin and subcutaneous adipose layer thickness in adults with diabetes at sites used for insulin injections: Implications for needle length recommendations. Curr Med Res Opin.2010;26(6):1519-1530.

- De Coninck C, Frid A, Gaspar R, et al. Results and analysis of the 2008–2009 Insulin Injection Technique Questionnaire survey. J Diabetes. 2010;2(3):168-179.

- American Diabetes Association. Position Statement: Insulin administration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 Suppl 1:S106-109.

- Johansson UB, Amsberg S, Hannerz L, et al. Impaired absorption of insulin aspart from lipohypertrophic injection sites. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):2025-2027.

- Do's and Don'ts: Safe Disposal of Needles and Other Sharps Used At Home, AT Work, or While Traveling. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.safeneedledisposal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/sharps_dos-and-donts.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- Safely Using Sharps (Needles and Syringes) at Home, at Work and on Travel. US Food and Drug Administration website. August 30, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ ProductsandMedicalProcedures/HomeHealthandConsumer/ConsumerProducts/Sharps/ucm20025647.htm. Accessed November 23, 2018.

- Adlersberg MA, Fernando S, Spollett GR, Inzucchi SE. Glargine and lispro: two cases of mistaken identity. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):404-405.

Back to Top