Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Contact Lenses: Choosing the Right Solutions

ABSTRACT:

A large portion of the U.S. population wears contact lenses on a regular basis. Many lens types exist, including soft lenses, rigid or gas permeable lenses, and hybrid lenses. Soft contact lenses are further categorized by material to specifically reflect their water content and ionic charges. Proper contact lens hygiene is crucial to prevent ocular complications and infections, but adherence to lens care routines is typically poor. Lens care systems can be multipurpose solutions (MPS) or hydrogen peroxide (HP)-based. Patients use MPS most often, but sometimes preservatives in these systems interact poorly with contact lenses or cause ocular conditions. HP-based systems generally cause fewer complications, but patients often find them too high-maintenance. Pharmacists are perfectly positioned in the community to answer questions about contact lens care and recommend solutions when lens-related eye problems occur. Pharmacists should counsel patients buying contact lens care products to ensure proper adherence and refer patients to eye care professionals when appropriate.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 45 million people in the United States (U.S.) today wear contact lenses, about 1 in 7 adolescents and 1 in 6 adults.1 Of those individuals, about 23% wear lenses that they replace daily, 22% weekly or bi-weekly, and 55% monthly. Additionally, about 15% use extended wear lenses, meaning they are worn continuously for up to 7 days and 6 nights.2 While pharmacies in the U.S. do not generally sell contact lenses, patients often present to pharmacists with questions about lens care and troubleshooting. Contact lenses’ main indications include correcting myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), astigmatism (distorted or blurred vision at any distance), and presbyopia (age-related loss of ability to focus on nearby objects).3 They also circumvent the inconveniences of eyeglasses, including fogging due to temperature changes, vision obstruction by frames, and tricky functioning while exercising. Lenses may also be helpful for patients with medical conditions like keratoconus or corneal abrasions.

While contact lenses are a generally safe and effective alternative for patients who do not want to wear eyeglasses full time or undergo corrective surgery, they come with risks. In general, contact lens wearers report more ocular symptoms than their non-contact lens wearing counterparts. These symptoms include dryness, soreness, grittiness, light sensitivity, pain, soreness, or itching. In fact, about 24% to 40% of patients discontinue contact lens use intermittently, or even permanently, due to symptoms of eye discomfort or redness.4 As many as 50% of contact lens wearers experience complications, but this number varies based on lens type, wearing schedule, and adherence to the prescribed care regimen.3 Fortunately, most lens-related complications are reversible, if treated promptly, stressing the importance for pharmacists to recognize them and understand their causes.

The Fairness to Contact Lens Consumers Act, passed in 2003, allows patients to obtain a prescription for their contact lenses and purchase lenses and related supplies from any authorized source.3 This raises concerns, as contact lenses are available from many nonprofessional sources that may employ individuals who may not have basic training in eye care. Individuals who buy contact lenses from Internet sources are less likely to adhere to proper lens care.3 This is particularly concerning, as online sales of eyeglasses and contact lenses continue to rise.

About 85% of individuals who wear contact lenses engage in behaviors that increase their risk of ocular complications, including serious lens-related eye infections.1 These behaviors include (1) sleeping or napping in contact lenses, (2) swimming in lenses, (3) replacing lenses and/or lens storage cases at longer intervals than recommended, and (4) not scheduling annual visits with eye care providers. Appropriate lens care and improved hygiene can prevent complications and interruption of contact lens wear. Pharmacists should have a general understanding of lens types, solutions, and possible eye complications to counsel their contact lens-wearing patients appropriately.

TYPES OF CONTACT LENSES

The concept of contact lenses is centuries-old, first introduced by the famed painter of the Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci in 1508.5 His “Codex of the Eye” sketches suggested that submerging the head in a bowl of water could alter vision. He created a glass lens with a funnel on one side so that water could be poured in it, but the device was impractical. In 1636, following on da Vinci’s work, French scientist René Descartes proposed placing a glass tube filled with liquid in direct contact with the cornea. While this invention worked somewhat to enhance vision, but it made blinking impossible. Contact lenses were attempted again in 1801 by English scientist Thomas Young. Young altered Descartes idea by reducing the size of the glass tube and then using wax to stick the water-filled lenses to his eyes. This was not practical, nor did it correct vision problems.6

Adolf Fick successfully constructed and fitted scleral lenses for the first time in 1888. These lenses were made of heavy blown glass, and he fitted them on rabbits and human volunteers using a dextrose solution. Fick’s lenses also had a maximum wearing time of only 2 hours. Contact lens technology has, thankfully, come a long way since. Plexiglass development in the 1930s allowed plastic contact lenses to be manufactured, followed by polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) in the 1960s. Upon realizing that low oxygen permeability of PMMA caused several adverse effects, researchers introduced gas permeable materials. By 1972, the first disposable soft lenses came about, and the first silicone hydrogel contact lenses were successfully manufactured in 1998.5 There are 3 main types of contact lenses used today: rigid, soft, and hybrid.

Rigid and Gas Permeable Contact Lenses

PMMA lenses are made from a transparent, rigid, plastic material. This same material, better known as Plexiglass, is used as a substitute for glass in shatterproof windows. PMMA lenses have excellent optics, but they do not permit oxygen to enter the cornea.7 These now outdated “hard contacts” have essentially been replaced by gas-permeable (GP) lenses. GP lenses are constructed of gas-permeable polymers, including (1) silicone acrylate, (2) fluorosilicone acrylate, (3) fluorosilicate acrylic, (4) siloxane acrylate, (5) fluorosiloxane acrylate, and (6) fluorosiloxanyl stirene.5 These lenses are less flexible and therefore adapting to them can take weeks. After the initial adaptation period of a few weeks, most people do find that GP lenses are as comfortable as soft lenses.3

Advantages of GP lenses include increased oxygen transmissibility, reduced lipophilicity (less contamination from the environment), and improved visual acuity. When properly cared for, GP lenses can also be reused repeatedly for months to years before replacement is necessary, making them more economical than other lens types.3

Soft Contact Lenses

The most common choice among contact lens wearers are soft lenses.1 These lenses are made of soft, flexible plastics called hydrogels that are more comfortable and flexible than rigid lenses.5 Patients typically adapt to wearing soft lenses within days. Soft lens hydrogels also allow oxygen to pass through the cornea.1,7 The cornea is designed for normoxia (normal oxygen levels) during the day and lower levels of oxygen provided through the eyelid at night. It is important for the eye to remain as highly oxygenated as possible to prevent long-term consequences, including8

- corneal edema (swelling of the cornea)

- epithelial microcysts (vesicles containing fluid and debris on corneal surface)

- limbal hyperemia (buildup of blood in vessels, leading to eye redness)

- corneal neovascularization (invasion of new blood vessels into the cornea)

- refractive error changes and corneal distortion (blurry or distorted vision)

The oxygen permeability of soft lenses, therefore, permits longer periods of wear and provides significant health advantages to the patient.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) created a classification system for soft contact lenses in 1985. This system originated with 4 groups, shown in Table 1, based on hydrogel ionicity (surface charge) and water content. FDA designed this classification to facilitate testing of contact lens care systems with different lens materials. Today, the classification system helps practitioners make decisions based on lens properties and information about how different care solutions interact with the lenses chosen.3,9 Lenses with ionic surface charges are more reactive than their nonionic counterparts. Nonionic lenses are often preferred, as they deter the formation of charged protein and lipid deposits.3

| Table 1. FDA Classification of Soft Hydrogel Contact Lenses3,9 |

| |

Nonionic |

Ionic |

|

Low Water

|

GROUP 1

Polymacon

Tetrafilcon A

|

GROUP 3

Phemfilcon A

|

|

High Water

|

GROUP 2

Alphafilcon A

Nelfilcon A

Omafilcon A

|

GROUP 4

Etafilcon A

Methafilcon A

Ocufilcon D

|

| |

GROUP 5: Silicone hydrogels

|

| *not a complete list of examples |

Silicone hydrogels are more porous and, therefore, have better oxygen permeability than hydrogels.5 When silicone hydrogel lenses hit the market in 2002, FDA originally classified them as either group 1 or 3 materials. However, silicone hydrogel lenses have a unique structure, including free versus bound water, pore size, preservative update and release, and lipid affinity. This led to material-solution incompatibility, resulting in corneal staining (see Sidebar: Corneal Staining). Therefore, FDA classified them into their own category.9 Silicone hydrogel lenses became the most common lens type used in the U.S., worn by about 76% of lens wearers today.2

| Sidebar: Corneal Staining10

Corneal staining refers to the appearance of these tissue disruption and pathophysiologic changes on the cornea seen with the aid of fluorescein (fluorescent dye). Causes include

- hypoxia

- deposits/foreign bodies

- chemicals

- lens fit/irregularities

- tear film disruption

Depending on the cause, redness and lacrimation can sometimes accompany severe staining.

|

Hybrid Contact Lenses

Hybrid contact lenses have a central optical zone of gas-permeable polymer surrounded peripherally by a silicone hydrogel.5 This combines the comfort of soft lenses with the clearer optics of a rigid lens. Hybrid lenses have limited popularity due to5

- difficult application and removal

- longer time to settle/adjust

- more frequent replacement

- higher costs

Most patients simply prefer soft contact lenses for comfort and ease of use.

A PLETHORA OF PRODUCTS

Patients use modern contact lens care products to clean, rinse, disinfect, and store lenses when they are not in use.9 The goals of contact lens cleaning are (1) removal of debris from the lens surface, (2) prevention of protein accumulation, and (3) disinfection from organisms that can bind to the lens surface and potentially cause infection.3 A lens care product must be sufficiently effective to kill pathogenic microbes, yet remain relatively harmless to the human eye. Contact lens solutions are generally made up of 4 major ingredient types9:

- biocides

- wetting agents and surfactants

- chelating or sequestering agents

- buffering agents.

Active ingredients used most commonly in contact lens solutions are listed in Table 2.

| Table 2. Components Most Commonly Used in Contact Lens Solutions9 |

| Ingredient Type |

Examples |

|

Biocides

|

alexidine

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB)

polyquaternium-1 (Polyquad)

myristamidopropyl dimethylamine (Aldox)

|

|

Surfactants/wetting agents

|

hyaluronan

hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC)

poloxamer 237

poloxamine

poly(oxyethylene)–poly(oxybutylene) (Hydraglyde)

pluronic 174R

pluronic F127

tetronic 904

tetronic 1304

|

|

Chelating/sequestering agents

|

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)

hydroxyalkylphosphonate (hydranate)

sodium citrate

|

|

Buffering agents

|

borate

citrate

phosphate

|

Biocides

Biocides are bioactive material added to a system with the intention of killing microbes. Literature often uses the terms biocide, disinfectant, and preservative interchangeably because they accomplish similar goals. However, disinfectants and preservatives are subtypes of biocides, and they are technically different. Disinfectants are designed to kill microbes quickly, while preservatives are designed to act over a longer period to maintain low levels of microbial contamination.9

A risk of contact lens wear is bacterial keratitis, a bacterial infection of the cornea. Symptoms include pain/redness in the eye, blurred vision, sensitivity to light, excessive tearing, and eye discharge. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (found in soil and water) and Staphylococcus aureus (found on human skin) are implicated in causing bacterial keratitis. Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes up to 70% of lens-associated keratitis.11,12 In contact solution, biocides’ main purpose is not to remove all microorganisms. Their purpose is to reduce the number of Acanthamoeba (amoeba found in soil and fresh water), bacteria, viruses, and fungi to safe levels.9

Contact solutions can be categorized as either multipurpose solutions (MPS) or hydrogen peroxide (HP)-based systems. The major difference between these formulations is that HP-based systems’ primary disinfectant is 3% hydrogen peroxide, which cannot be applied directly to the eye. They require a special lens case that breaks down and neutralizes the peroxide before a lens can be placed on the eye. Some newer HP-based solutions also incorporate chemicals designed to condition lenses and improve patient comfort.9

Many MPS systems utilize polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) as a biocide. PHMB has a strong cationic charge. Some studies show that this can cause it to infiltrate the contact lens matrix and release into the patient’s eye over time. This “uptake and release” can cause corneal staining, decrease antimicrobial efficacy, and increase patient discomfort (e.g., a gritty, scratching sensation).9 Some lens materials are more susceptible to this phenomenon than others. Polyquaternium-1 (Polyquad) is another biocide used in MPS that undergoes uptake and release due to its cationic charge. However, this is very formula-dependent and its action is often offset by additional ingredients that work against the ionic forces. Polyquad also has a much larger molecular weight than PHMB, which helps reduce a toxic uptake and release mechanism.9 Polyquad is typically not used alone in MPS; in fact, patients report an 88% increase in comfort using solutions that combine it with alexidine.

Wetting Agents and Surfactants

“Surface active agents,” also known as surfactants, have hydrophilic (water-loving) heads and hydrophobic (water-hating) tails, so they are soluble in both water and organic solvents. This gives them dual purpose. Surfactants act as surface cleaners by removing surface deposits from lenses, and wetting agents by decreasing the surface tension of liquids applied to the lens surface. Among all the solution components, surfactants have the greatest positive influence on contact lens comfort.9 Generally, solutions with surfactants have surface tension values closer to that of tears, while those without more closely resemble surface tension values of water. HP-based solutions also use wetting agents to enhance comfort, and studies report that this improves wettability of various lens types.

Chelating and Sequestering Agents

Chelating agents work with preservatives to enhance cleaning capabilities of contact lens solutions. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is a cationic chelating agent commonly found in lens cleaning systems. It binds to free metals, increasing microbes’ susceptibility to preservative penetration, thus improving antimicrobial activity of biocides.9,11

Sodium citrate and hydranate are sequestering agents. Sodium citrate aids in passive protein removal. Hydranate is multifunctional. Its multiple negative charges attract proteins in the tears, which separates them from the lens surface by repulsive charges. It also forms a complex with calcium, breaking links between calcium deposits and the lens surface.9,11

Buffering Agents

Contact solutions include buffering agents (i.e., weak acids or bases) to maintain the solution’s acidity (pH), typically between 7 and 7.4. Solutions are typically highly buffered, as variation from a stable pH can significantly decrease lens comfort. Buffering agents also prevent rapid changes to the solution when it is exposed to other acids and bases.9 Phosphate buffers are generally more physiologically compatible with tissues, but they may easily become contaminated. Borate buffers, however, have a microbiological advantage, and they may also remove lysozyme (an enzyme that can build up on lenses) from a solution.9

PROPER USE OF LENS SOLUTIONS

For the remainder of this CE, readers need to remember that we will be talking about 2 types of contact lens solutions: multipurpose solutions (MPS) and hydrogen peroxide (HP)-based. Improper use of contact lens cleaning systems can affect the safety and comfort of contact lenses, and pharmacists should be prepared to counsel patients on lens care best practices.

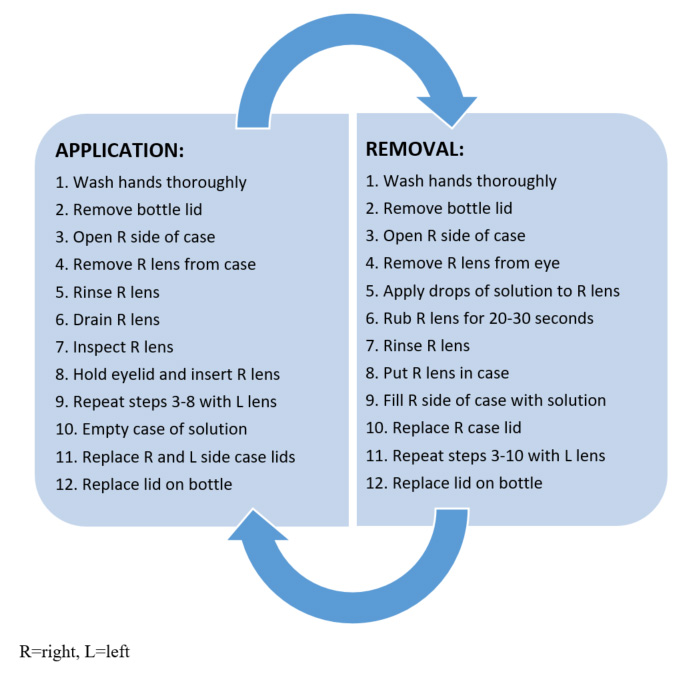

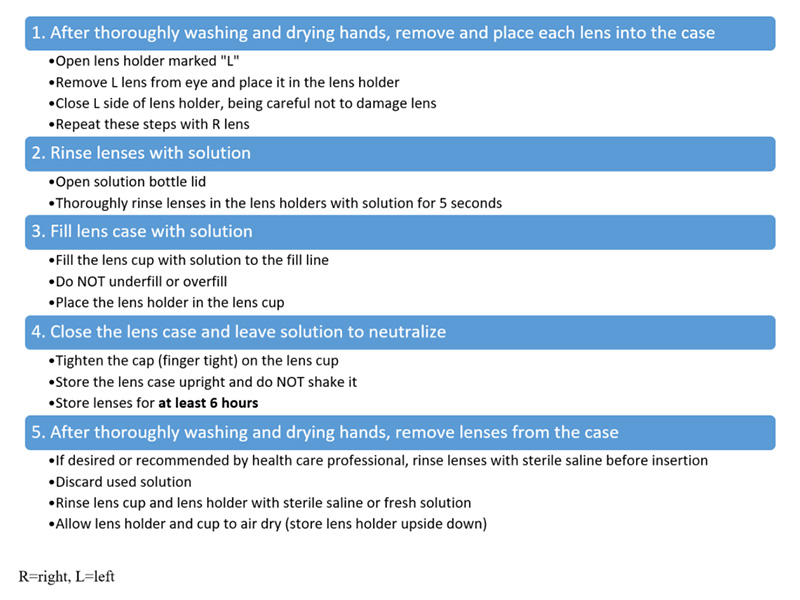

MPS are generally considered easier to use than HP-based systems, but proper use of MPS requires many steps, shown in Figure 1. Although MPS remain the most commonly used, HP-based lens care systems are growing in popularity. In 2009, 14.7% of patients were using MPS, and that rose to 22% in 2016.13 Therefore, pharmacists should be prepared to counsel on the proper use of either system. Appropriate steps for HP-based contact lens solution use are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Steps for Proper Daily Lens Care with MPS Use3,14

Figure 2. Steps for Proper Daily Lens Care with HP-Based Solution15

Patients who use HP-based systems must observe strict safety measures. Storing lenses for 6 hours is important to allow the HP solution to completely neutralize. Patients should never put HP solution that has not been neutralized directly in the eye. HP-based solutions are supplied with a red cap to warn patients of this fact. If non-neutralized solution enters the eye, patients must flush the eyes with a large amount of water or sterile saline for a few minutes. If burning/stinging does not resolve, they should seek assistance from an eye care professional.15 Pharmacists should also advise patients not to use over-the-counter (OTC) peroxide in place of their lens solution. The neutralized pH of OTC hydrogen peroxide is significantly lower (3.35 to 4.77) than the ocular comfort range (6.6 to 7.8), and can cause substantial stinging and discomfort.9

If patients do not intend to wear lenses immediately after disinfection, they can be stored in the neutralized solution for up to 7 days.15 After this time, patients should clean lenses again prior to wear. If bubbles leak from the hole in the top of the lens case cap, non-neutralized HP solution may be present. Patients should empty solution from the case, thoroughly rinse the lens holder and cup with fresh solution and repeat the disinfection steps. Advise patients to wash hands thoroughly before handling lenses or touching their eyes to prevent non-neutralized solution from entering the eye.15 Also, patients must not reuse, “top off,” or dilute/mix HP-based solution; fresh solution is needed on every cleaning occasion. They must use only the provided lens case and never a flat lens case.

Users of any contact lens solution, regardless of the type, should also follow these guidelines, which are often missing from care system instructions14:

- after washing hands, dry them before handling lenses

- replace lens case lids overnight to prevent contamination

- keep the bathroom clean, especially faucet handles

- store lens case away from wash basins and toilets

- periodically wipe out lens case with a tissue to remove grunge

- replace lens case frequently, ideally every month or at least with each new bottle

CASE STUDY: Jeffrey, a 29-year-old traveling salesman, comes to your pharmacy to pick up a prescription eye drop for an infection. He wears silicone hydrogel contact lenses and uses a HP-based lens care system. He tells you sometimes he leaves his contacts at home, wearing only his glasses on week-long business trips. He likes that his HP-based solution is neutralized as soon as he returns home so he can wear his lenses to the beach. What changes do you suggest to his lens care routine?

Adherence to Proper Lens Care

A study of international contact lens compliance showed that full adherence to proper lens care was rare. These researchers also identified 8 modifiable behaviors that contribute to increased risk of contact lens-associated infections16:

- inadequate hand washing

- non-prescribed overnight wear (accidental or intentional)

- excessive duration of extended wear

- excessive lens replacement interval

- inadequate case cleaning

- failure to use correct disinfecting solution (i.e., no disinfection or stored in tap water)

- failure to rub and rinse lenses

- topping off solution (i.e., not replacing with fresh solution for each storage occasion)

Study respondents were more likely to be less adherent if they were: (1) younger, (2) male, and (3) full-time contact lens wearers (versus part-time wearers). Patients were also more adherent if they had seen an eyecare practitioner more recently.16

The lens care step patients miss most frequently is case cleaning.16 This is a concern, given that lack of case cleaning is associated with a 4-fold increase in microbial keratitis. To properly clean a contact lens case, patients should (1) empty all solution from the case, (2) rinse the case with fresh solution, (3) rub the inside of the case with clean fingers, (4) air dry the case upside down with the caps off. If the case has a silver nitrate lining to decrease biofilm formation, patients should leave the caps on while the case dries, so as not to disrupt that function. Patients should also occasionally run their lens case through the dishwasher to disinfect it, or they can boil it in a pot of water for 5 minutes to do the same.17 After cleaning, rubbing and rinsing lens cases, correct replacement interval and handwashing are the most frequently omitted steps.16 Rubbing and rinsing lenses can reduce bacterial load on the lens surface by 99.9%. Pharmacists should stress this point with users of MPS.

A 2007 survey found that adherence to directions for use was 100% among HP-based solution users but only 37% among MPS users.18 A 2016 study also found that patients using HP-based systems tend to be more adherent to proper lens care. HP-based solution users were 4 times less likely to reuse care solution and 7 times less likely to use their lens case longer than 3 months.19 These behaviors are largely reinforced by the nature of the solution. When using a HP-based system, the solution reacts with the platinum disc in the case causes vigorous bubbling. This bubbling is maintained effectively with fresh solution and a frequently replaced case, reinforcing positive lens care behaviors. This visual clue may explain why HP users are more likely to remain adherent to using fresh solution and a fresh case.

HOW DO YOU CHOOSE?

Proper selection of lens care products can affect the safety and comfort of contact lenses. Pharmacists should be prepared to help patients navigate the many options and make appropriate choices based on their contact lens type and lifestyle factors.

Efficacy

Many studies have compared the efficacy of MPS and HP-based contact solutions against microbial and fungal growth. Efficacy of these lens care types is comparable to prevent planktonic (swimming) growth of keratitis-causing bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens, and Staphylococcus aureus.20,21 Microbial biofilms and Acanthamoeba trophozoites and cysts, however, appear more susceptible to HP-based systems.20,22-25 HP-based systems are at least equally effective at preventing corneal infiltrative events compared with MPS, if not more effective.4,26,27

Comfort

Many ingredients are added to contact lens solutions that can improve comfort. Studies show that a lubricant (e.g., hydroxypropylmethylcellulose) specifically improves wetting of silicone hydrogel lenses. In fact, the lubricant binds to the lens surface and releases into the eye during wear, reducing dryness for the patient.9 Patients with allergies and/or more sensitive eyes also tend to prefer HP-based systems. They report less grittiness, end of day dryness, and irritation with HP-based solutions.28 A study comparing MPS versus HP-based systems for silicone hydrogel lenses found no significant difference in total lens wearing time, comfort, or dryness ratings.29 However, researchers did find that comfortable wearing time was longer when using HP-based contact solution. They speculated that this was likely because HP-based systems have a significantly higher surface tension, lower pH, and lower osmolality than MPS. They also lack a preservative, which can be irritating to patients.

Lifestyle Factors

As both MPS and HP-based systems are appropriate for soft or rigid contact lenses, often selection of a contact lens solution comes down to lifestyle factors. For example, patients who are part-time contact lens-wearers or who travel frequently should use MPS because microorganisms may regrow in neutralized HP solutions after 7 days. Patients who cannot commit to leaving lenses in solution for 6 hours or more each evening should also avoid HP-based solutions. HP-based care systems may be a better choice for patients with adherence issues or those experiencing sensitivity to preservatives in MPS.

Other Considerations

Most contact lens-wearers use MPS. They boast benefits of convenience, simplicity, and disinfection properties for part-time wear. Preservatives in MPS, however, can absorb into silicone hydrogel lenses during overnight disinfection and subsequently release into the eye during the day. This can lead to significant corneal staining.30 While they are often not the solution of choice, HP-based systems show considerable advantages over MPS. Studies of senofilcon A and balafilcon A lenses show improved wettability with less mucus and lipid deposits using a HP system.31 Another study showed greater corneal staining and infiltrative events with MPS versus a peroxide system.32

Some contact lens types react poorly with certain ingredients. For example, group 4 lenses undergo 60% uptake of PHMB, the most uptake and release of PHMB of any lens type.9 When lenses absorb PHMB, its levels in the solution fall. This leads to a considerable loss of antimicrobial and antifungal activity. Some materials, like lotrafilcon A, experience changes to their elasticity or flexibility when exposed to HP-based cleaning systems.9 This can decrease ocular comfort.

CASE STUDY: Wendy, a 43-year-old nurse, comes to your pharmacy looking for a recommendation on contact solution that is better compatible with her etafilcon A lenses and her lifestyle. Wendy often works double-shifts as a nurse and takes a short nap during her lunch break. Which type of contact lens solution would you suggest for her? What lens hygiene tips should you emphasize?

Safety can be a concern with HP-based solutions given the risk of burning and stinging with insufficiently neutralized solution. FDA investigated HP-based lens care-related Medical Device Reports (MDRs) received over a 10-year period. Investigators noted 370 MDRs reported, with causes including33

- accidental use (168 reports)

- incomplete neutralization due to insufficient time or inappropriate case (107 reports)

- accidental purchase (40 reports)

It is important to note that while these events can be serious, this total of 370 reports were over a period covering many millions of HP-based solution uses, making such incidents extremely uncommon.18 Among the most frequently reported problems were18

- burning sensation (210 reports)

- chemical eye burn (186 reports)

- corneal abrasion (33 reports)

There is no evidence suggesting risk of permanent ocular damage or vision loss following exposure to non-neutralized HP-based solution.18 Burning and stinging are typically transient and resolve without medical treatment. Pharmacists should identify patients who may benefit from a HP-based system and encourage them to try it, especially if they report poor experiences with MPS.

GOT A PROBLEM? HERE’S A SOLUTION!

Ocular complications are not uncommon for contact lens wearers. For many clinicians, the obvious means of correcting these issues is to switch either contact lens type or lens care product because each of these can potentially impact ocular comfort. Pharmacists cannot prescribe patients a new lens type, but they can help patients select an alternative contact solution when eye complications arise.

Corneal Staining

MPS can cause significant amounts of corneal staining. It is especially common when used with FDA group 2 lenses (high water content and neutral) and silicone hydrogel lenses.18 Specific ingredients are also implicated in corneal staining, including PHMB and Polyquad. Polyquad-containing MPS cause less corneal staining than PHMB because Polyquad has a higher molecular weight, and therefore, absorbs into and releases from the contact lens matrix at a lower rate.30 One study found that Polyquad only resulted in corneal staining for 2% of patients wearing balafilcon A lenses, while PHMB caused corneal staining in 37% of patients wearing the same lens type.34

Most evidence suggests that corneal staining is minimal with HP-based contact solutions.30 This is probably because peroxide solution neutralizes before lens insertion, so the ocular surface is not exposed to the active disinfectant as it is with MPS.

Corneal staining typically recovers within hours or days of removing the offending agent, as long as patients do not wear contact lenses during the recovery period.10 Pharmacists should recognize which lens and care product combinations can lead to corneal staining. They should recommend HP-based lens care systems when they suspect corneal staining. If a HP-based system is not ideal based on the patient’s lifestyle factors, pharmacists should help patients find a solution that utilizes Polyquad, rather than PHMB.

Ocular Dryness

Contact lens wear increases dryness and decreases ocular comfort. Patients who experience dryness may benefit from HP-based lens care systems, as they show lower rates of irritation, burning, itching, dryness, and blurriness.18 For those patients whom HP-based systems are not appropriate, pharmacists should recognize which wetting agents are superior to others. A study comparing 2 MPS with wetting agents found that tetronic 1304 led to enhanced comfort compared with poloxamine. This was especially true in group 4 lens-wearers.35 A similar study found that for silicone hydrogel-wearing patients, poly(oxyethylene)–poly(oxybutylene) (Hydraglyde) in MPS led to greater comfort and patient tolerability than poloxamine.36

Exposure to wind and high temperatures can also cause some lens dehydration, so rewetting drops can be helpful. Rewetting products are intended to clean and rewet the lens while it is in the eye. These solutions use surfactants to loosen deposits, and the natural cleaning action of blinking assists removal. Products with benzalkonium chloride preservative can stain lenses and should be avoided.3 Ideally, direct patients to preservative-free products or those specificically formulated for use with contact lenses.

Corneal Infiltrate Events

Corneal tissue is normally transparent. Sometimes, single or multiple discrete aggregates of gray or white inflammatory cells migrate into the cornea, referred to as corneal infiltrate events (CIE). Corneal infiltrates occur as a consequence of the inflammatory response to increased microbial burden. Contact solution preservatives and hypoxic conditions are responsible for more than 70% of the total risk of CIE with contact lens wear.37 CIE can be asymptomatic or lead to acute redness, peripheral ulcer, or keratitis. Hypoxia occurs with excessive duration of lens wear, stressing the importance of removing lenses while sleeping unless indicated. Pharmacists should encourage patients to remove and clean lenses regularly to prevent CIE.

Additionally, eyes that experience solution toxicity are more likely to experience a CIE. In fact, corneal inflammation is 3 times more likely to occur in contact lens wearing eyes experiencing toxic corneal staining than those that do not.38

OPTIMIZING THE PHARMACIST’S ROLE

As highly accessible health care providers, pharmacists should be prepared to field questions from contact lens wearers. They should advise them on hygiene measures, care product recommendations, and drug and cosmetic interactions to improve lens comfort and reduce risk of lens-related adverse events.

Hygiene Counseling

Patient counseling should include discussion of signs and symptoms of contact lens-related eye problems that indicate a need for medical care. If eye redness or pain or blurry vision occurs during lens wear, patients should remove the lens and see an eye care provider for evaluation.

Microbial contamination of contact lenses causes several eye diseases, and patients need proper lens care hygiene to prevent ophthalmic infections. Lens and case cleaning are crucial in the prevention of lens-related infections. Studies have shown that more than 90% of patients with a contaminated case also had contaminated lenses or solutions, demonstrating that bacteria can be transferred from the case to the lens.5 Bacteria are highly present in nature in the form of biofilms.5 Biofilms act as a cohesion media for microbes, making them stronger and more resistant to antibiotics, and biofilms in contact lens cases are thicker than those formed on lenses. Lens cases can develop moderate-to-heavy contamination after 2 weeks of use, which highlights the need to replace or sanitize them often. In addition to regular cleaning, patients should avoid water sources (e.g., swimming, showering, hot tubs) while wearing contact lenses. Microorganisms living in water can be transferred to the eye, increasing the risk of infection.

If patients are unable to adhere to proper lens care hygiene, daily disposable lenses are an option. Advantages of daily disposable lenses include3

- each lens is sterile before removal from the package for immediate insertion into the eye

- no cleaning regimen is necessary; the patient discards the lens after wear for a day

- deposit formation is minimal

- lens-related problems (e.g., conjunctivitis or allergic reactions to lens care solutions) occur less frequently

Daily disposable lenses can often be more expensive; using 730 daily contact lenses per year will generally cost more than, for example, using 24 monthly-replacement lenses per year. Some people also object to the amount of waste created by this lens type. Pharmacists can identify patients who are appropriate for this lens type and refer them to an eye care provider for evaluation.

Lens Care Product Reactions

As discussed, patients can have adverse reactions to contact lens care products. Often, patients buy contact solution based on price alone without regard to lens compatibility or possible eye complications.3 Pharmacists should be prepared to assist patients in replacing their current cleaning regimen when appropriate based on the nuances of ingredients and their compatibility with contact lens materials discussed above.

Saline alone was once used to clean lenses, but it is now recognized that saline alone lacks disinfecting properties and should not be used alone. In the event of reaction to a solution, pharmacists can recommend a final saline rinse before lens insertion or a change to another MPS that uses a different preservative. Preservative free saline solutions are also available for extremely sensitive patients, but they must be used within 30 days and then discarded.3

Drug and Cosmetic Interactions

Some systemic medications can affect the eyes. When patients present with ocular complications, pharmacists should inquire about new medications. In general, drugs with anticholinergic activity can reduce tear volume and, therefore, induce dry eye. Many OTC medications can decrease tear volume (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, ibuprofen, acetaminophen), so pharmacists should advise contact lens wearing patients that they may need rewetting agents during their use.3 Hormones—including hormonal birth control—can also alter tear volume and the shape of the corneal surface. This causes blurred vision and contact lens intolerance.3 Additionally, some brightly colored drugs (e.g., rifampin, phenazopyridine, sulfasalazine) are secreted into the tears, leading to staining of both tears and lenses.3

In general, counsel patients not to place any ophthalmic medication—solution, suspension, gel, or ointment—into the eye while contact lenses are in place. Soft lenses, especially, can absorb chemical compounds from these preparations. The lens then either releases the medication over time, creating a sustained-release effect, or binds it so tight that none of it is released into the eye.3 Pharmacists filling prescriptions for ophthalmic medications should inquire about contact lens use. If the medication is for a contact lens-related issue, counsel patients to refrain from wearing lenses until the issue resolves. Otherwise, if the medication is compatible with contact lenses, counsel patients to wait 15 minutes after administration to insert contact lenses. When in doubt, direct patients to their eye care provider for guidance.

Contact lens-wearing patients should also choose and use cosmetics with caution. They should insert lenses before applying makeup and avoid touching the lens with applicators. Water-based cosmetics, moisturizers, and makeup removers are preferable, as oil-based formulations can deposit onto the lens, causing blurred vision and irritation.3

CONCLUSION

A large portion of the U.S. population wears contact lenses on a regular basis. Pharmacists are positioned in the community to answer questions about contact lens care and recommend solutions when lens-related eye problems occur. Many lens and care system options exist, but the majority of patients wear soft contact lenses (particularly silicone hydrogel lenses) and utilize MPS lens care systems. HP-based care systems can be an excellent alternative, and pharmacists can identify patients for whom they are appropriate. MPS and HP-based systems have many steps to follow for proper lens care, and adherence is poor. Pharmacists should counsel patients buying contact lens care products to ensure proper adherence and refer patients to eye care professionals when appropriate.

RESOURCES

|

American Optometric Association: Contact Lens Care

Answers to frequently asked questions about contact lenses, including a “do’s and don’ts” list

|

https://www.aoa.org/healthy-eyes/vision-and-vision-correction/contact-lens-care

|

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Healthy Contact Lens Wear and Care

Information for patients on healthy contact lens wear and care

|

https://www.cdc.gov/contactlenses/protect-your-eyes.html

|

REFRENCES

- Cope JR, Collier SA, Nethercut H, et al. Risk behaviors for contact lens-related eye infections among adults and adolescents — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(32):841-845.

- Contact Lens Spectrum. International contact lens prescribing in 2017. January 1, 2018. Accessed at: https://www.clspectrum.com/issues/2018/january-2018/international-contact-lens-prescribing-in-2017, August 22, 2020.

- Chen AMH, Straw AM. Prevention of contact lens-related disorders. In: Krinsky DL, Ferreri SP, Hemstreet BA, Hume AL, Newton GD, Rollins CJ, Tietze KJ, eds. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs. 19th ed. Washington, DC: APhA Publications;2018:567-589.

- Richdale K, Sinnott LT, Skadahl E, Nichols JJ. Frequency of and factors associated with contact lens dissatisfaction and discontinuation. Cornea. 2007;26(2):168-174.

- Moreddu R, Vigolo D, Yetisen AK. Contact lens technology: from fundamentals to applications. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(15):e1900368.

- Eye Society (1 800 Contacts). Da Vinci to disposable: A history of contact lenses. Accessed at: https://www.1800contacts.com/eyesociety/da-vinci-to-disposable-a-history-of-contact-lenses/, August 22, 2020.

- All About Vision. Contact lens basics: Types of contact lenses and more. Updated June 2018. Accessed at: https://www.allaboutvision.com/contacts/contact_lenses.htm, August 22, 2020.

- Contact Lens Spectrum. The Future of Contact Lenses: Dk Really Matters. February 1, 2006. Accessed at: https://www.clspectrum.com/supplements/2006/february-2006/protecting-your-patient-s-eye-health/the-future-of-contact-lenses-dk-really-matters, August 22, 2020.

- Kuc CJ, Lebow KA. Contact lens solutions and contact lens discomfort: examining the correlations between solution components, keratitis, and contact lens discomfort. Eye Contact Lens. 2018;44(6):355-366.

- Efron N. Contact Lens Complications. 4th ed. Philadelphia.: Elsevier; 2020:197-209.

- Jones L, Powell CH. Uptake and release phenomena in contact lens care by silicone hydrogel lenses. Eye Contact Lens. 2013;39(1):29-36.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy contact lens wear and care: basics of bacterial keratitis. Updated April 2014. Accessed at: https://www.cdc.gov/contactlenses/bacterial-keratitis.html, August 22, 2020.

- Alcon. The realities of hydrogen peroxide lens care use & misuse in today's marketplace. March 1, 2017. Accessed at: https://www.fda.gov/media/103874/download, August 22, 2020.

- Contact Lens Spectrum. Diligent disinfection in 49 steps. February 1, 2012. Accessed at: https://www.clspectrum.com/issues/2012/february-2012/reader-and-industry-forum, August 22, 2020.

- Clear Care Plus [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Alcon; 2018.

- Morgan PB, Efron N, Toshida H, Nichols JJ. An international analysis of contact lens compliance. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2011;34(5):223-228.

- Eye Society (1 800 Contacts). How to clean your contact lens case. Accessed at: https://www.1800contacts.com/eyesociety/how-to-clean-your-contact-lens-case/, August 22, 2020.

- Nichols JJ, Chalmers RL, Dumbleton K, et al. The case for using hydrogen peroxide contact lens care solutions: a review. Eye Contact Lens. 2019;45(2):69-82.

- Contact Lens Spectrum. Is there a relationship between care system and compliance? April 1, 2016. Accessed at: https://www.clspectrum.com/issues/2016/april-2016/is-there-a-relationship-between-care-system-and-co, August 22, 2020.

- Szczotka-Flynn LB, Imamura Y, Chandra J, et al. Increased resistance of contact lens-related bacterial biofilms to antimicrobial activity of soft contact lens care solutions. Cornea. 2009;28(8):918-926.

- Rosenthal RA, Buck S, McAnally C, et al. Antimicrobial comparison of a new multipurpose disinfecting solution to a 3% hydrogen peroxide system. CLAO J. 1999;25(4):213-217.

- Wilson LA, Sawant AD, Ahearn DG. Comparative efficacies of soft contact lens disinfectant solutions against microbial films in lens cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(8):1155-1157.

- Kilvington S, Lam A. Development of standardized methods for assessing biocidal efficacy of contact lens care solutions against Acanthamoeba trophozoites and cysts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(7):4527-4537.

- Mowrey-McKee M, George M. Contact lens solution efficacy against Acanthamoeba castellani. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33(5):211-215.

- Shoff ME, Joslin CE, Tu EY, et al. Efficacy of contact lens systems against recent clinical and tap water Acanthamoeba isolates. Cornea. 2008;27(6):713-719.

- Carnt NA, Evans VE, Naduvilath TJ, et al. Contact lens-related adverse events and the silicone hydrogel lenses and daily wear care system used. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(12):1616-1623.

- Chalmers RL, Wagner H, Mitchell GL, et al. Age and other risk factors for corneal infiltrative and inflammatory events in young soft contact lens wearers from the Contact Lens Assessment in Youth (CLAY) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(9):6690-6696.

- De la Jara P, Papas E, Diec J, et al. Effect of lens care systems on the clinical performance of a contact lens. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:344-350.

- Keir N, Woods CA, Dumbleton K, Jones L. Clinical performance of different care systems with silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33(4):189-195.

- Andrasko G, Ryen K. Corneal staining and comfort observed with traditional and silicone hydrogel lenses and multipurpose solution combinations. Optometry. 2008;79(8):444-454.

- Guillon M, Maissa C, Wong S, et al. Effect of lens care system on silicone hydrogel contact lens wettability. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2015;38(6):435-441.

- Soni PS, Horner DG, Ross J. Ocular response to lens care systems in adolescent soft contact lens wearers. Optom Vis Sci 1996;73:70–85.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 17th Ophthalmic Devices Panel and RCAC Planning Meeting Executive Summary. Accessed at: https://www.fda.gov/media/103429/download, August 27, 2020.

- Jones L, MacDougall N, Sorbara LG. Asymptomatic corneal staining associated with the use of balafilcon silicone hydrogel contact lenses disinfected with a polyaminopropyl biguanide-preserved care regimen. Optom Vis Sci 2002;79:753-761.

- Stiegemeier MJ, Friederichs GJ, Hughes JL, et al. Clinical evaluation of a new multi-purpose disinfecting solution in symptomatic contact lens wearers. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2006;29:143-151.

- Corbin G, Kading D, Powell S, et al. Clinical evaluation of a new multipurpose disinfecting solution in symptomatic wearers of silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Clin Optom. 2012;4:13-24.

- Review of Cornea & Contact Lenses. The infiltrate debate: material matters. January 8, 2013. Accessed at: https://www.reviewofcontactlenses.com/article/the-infiltrate-debate-material-matters, August 22, 2020.

- Carnt N, Jalbert I, Stretton S, et al. Solution toxicity in soft contact lens daily wear is associated with corneal inflammation. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(4):309-315.

Back to Top