Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Mind-Body Medicine: The Power of Self-Awareness and Self-Care

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) has served as an important source of information to monitor the health of the nation. Data from NHIS consistently shows that alternative medicine has an enormous presence in the United States health care system. According to data from the 2017 NHIS, the number of American adults using yoga and meditation has significantly increased over previous years and the use of chiropractic care has increased modestly for adults.1 In analyzing the 2007 NHIS results, alternative medicine was more prevalent in adults with at least one neuropsychiatric symptom (43.8%) as opposed to adults without neuropsychiatric symptoms (29.7%).2 Neuropsychiatric symptoms surveyed included depression, anxiety, insomnia, attention deficits, headaches, excessive sleepiness, and memory loss. The higher the number of neuropsychiatric symptoms, the higher the prevalence of alternative medicine use, particularly mind–body therapies.2 It is quite evident from this data that patients are using more alternative approaches to therapy. For that reason, it is critical that those providing health care take an educated approach to the principals of alternative medicine. This manuscript will specifically focus on the interventions involved in mind-body medicine.

EVOLUTION OF CONVENTIONAL MEDICINE AND INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE

While pharmaceutical and surgical therapies have been central to advances in medical treatment, there has been a growing awareness of therapies used in place of conventional medicine. The United States’ National Institutes of Health (NIH) addressed this interest by establishing the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). Complementary approaches to health care have grown to the point that Americans no longer consider them an alternative to health care. Thus, the term integrative medicine was established which emphasizes the concept of integrating elements of what has been thought of as complementary or alternative medicine into the conventional medicine approach, particularly those with evidence to support their use. A five-domain system for classifying complementary and alternative medicine modalities was established by NCCIH and can be found in Table 1.3 These five domains remain a useful framework for organizing thoughts on various approaches and practices.

| Table 1. The Five Domains for Classifying Complementary and Alternative Medicine Modalities3 |

| Domain |

Examples |

| Biologically based therapies |

Dietary interventions, vitamins and minerals, supplements, herbs, botanicals |

| Mind-body interventions |

Biofeedback, hypnosis, meditation, guided imagery, relaxation techniques, yoga, tai chi, and qigong |

| Manipulative and body-based methods |

Chiropractic care, massage therapy, reflexology, rolfing, osteopathy |

| Alternative or Whole Medical Systems |

Homeopathy, naturopathic medicine, Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, traditional African medicine, traditional Mayan medicine |

| Energy Therapies |

Reiki, acupuncture, tai chi, therapeutic touch, bioenergetic therapy, qigong |

We can see from this framework that there are multiple practices that fit into each domain. Of these practices, mind-body based approaches are among the most commonly used integrative health approaches, and they continue to increase in popularity.4 We begin by exploring what is meant by the science of mind-body medicine.

DEFINITION OF MIND-BODY MEDICINE

Mind-body complementary health approaches are a diverse group of health care practices focused on the relationships between the mind, body, brain and behavior. The primary objective of mind–body medicine is to utilize the mind to positively affect one's overall health. According to the NIH, mind-body medicine is the discipline that explores the interactions among the brain, body, mind and behavior as well as the ways in which emotional, mental, social, spiritual, experiential and behavioral factors can directly affect health.5 It is a field in medicine that uses a variety of techniques designed to enhance the mind’s capacity to affect bodily function and symptoms. Mind-body medicine includes behavioral and psychosocial interventions among the first line of interventions. The patient is given an active role from the beginning in developing a treatment plan and takes majority of the responsibility for directing the psychosocial and lifestyle aspects of that plan. Mind-body medicine emphasizes patient education and patient self-management as integral parts of clinical practice.6

There is an inextricable connection between physical and mental disorders. Therefore, the approach to identifying this connection and the science that brings these two types of treatment into a common modality serves as complimentary to other traditional approaches in healing the mental and physical states and promoting the patient’s wellbeing.

A HISTORY LESSON IN MIND-BODY EVOLUTION

The relationship between mind and body and its importance to health has been recognized for thousands of years by all major healing traditions. Historically, relationships between the mind and body have been studied by healers as early as ancient Greece. Healers such as Hippocrates recognized the moral and spiritual aspects of healing. The consensus being that treatment could occur only with consideration of attitude, environmental influences, and natural remedies. This concept that the mind and spirit both have an essential role in fostering healing was embraced by both Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine. 7 In a split from the traditional healing systems in the East, developments in the Western World began focusing their attention on newly discovered scientific concepts instead of spirituality and natural measures.

Western medicine became dominated by the reductionism theory.7 Reductionism is an approach that is used in many scientific disciplines that is centered on the belief that something can best be explained by breaking it down into its individual parts. It is often contrasted with holism, which is focused on looking at things as a whole. Where a reductionist would propose that the best way to understand something is to look at what it is made up of, a holist would argue that the sum-product is more than simply the sum of its parts. Reductionism can be quite helpful in some types of research, but in many cases, the sum is much more than simply the total of its pieces. The complete item in question has what are known as emergent properties that are simply not present in its smaller pieces.8 This reductionist approach began to consider the mind as merely a part of the whole system (aka body). Since the mind was simply a small piece of the entire entity, scientists began to believe that although the body could affect the mind, no interaction was possible in the opposite direction. In other words, the mind could not affect the body on its own. The discovery of new technology and later medications further dispelled the notion of the mind influencing the body.7

In the 1920’s the medical world began to see some scientific proof of the mind-body connection. Due to the work of Walter Cannon who coined the phrase, “fight or flight response”, it became evident that there was a direct relationship between stress and an endocrine response.7 During World War II, the placebo effect was unearthed which began to shed more light on this connection. Henry Beecher, an army medic, ran out of morphine for treating wounded soldiers in the field. In hopes of reducing their fear and anxiety, he replaced the solution with saline but told the soldiers it was morphine. Surprisingly, almost half of the soldiers reported reduced pain.7 This phenomenon led to postulations that there were chemicals mediating communications and connections between the mind and body. Finally, some scientific basis for the connection was established.

Since then, there has been considerable research evaluating the clinical effects of mind-body medicine. The conditions which cause human suffering today, in the affluent societies of the developed world, are caused as much by lifestyle, dietary habits, activity level, and life-stressors, as they are by such traditional causes of disease like infection, viruses, bacteria and physical trauma. The mind-body medicine approach creates a partnership among specialists in the medical and mental specialties. The result is an integrated team of caregivers who address mind, body, and spirit in each health care visit. It is no longer the reality of the modern world where the relationship between the mind and body are neglected.

MIND BODY THERAPIES

Mind-body therapies are used throughout the world in treatment, disease prevention, and health promotion. These therapies are a large and diverse group of procedures or techniques that are administered by a trained practitioner. Table 2 lists the different mind-body therapies that will be discussed in this section.

| Table 2. Mind-Body Therapies |

| Therapy |

| Biofeedback |

| Hypnosis |

| Guided Imagery |

| Yoga |

| Tai chi |

| Qigong |

| Meditation |

Biofeedback

The practice of biofeedback involves a technique through which patients voluntarily learn to control autonomic activity, once thought to be involuntary body processes. The patient receives information from sensors that monitor psychophysiological changes in the body such as brainwaves, breathing patterns, heart rate, skin temperature, sweat gland activity and muscle tension. The primary goal of biofeedback is to balance this autonomic activity, which in turn helps a patient reduce sympathetic overflow. This type of intervention requires specialized equipment and a trained biofeedback practitioner who serves as a guide teaching the patient to use the feedback to regulate their physiology. Biofeedback helps to make patients aware of the thoughts, feelings and behaviors related to their physiology and eventually over time, the patient can hopefully learn to self‐regulate without feedback screens in front of them and thus regulate their physiology in a healthy direction. 9

Biofeedback therapy is a process of training as opposed to a treatment. The patient must take an active role and practice in order to develop the skill, much like learning to ride a bike. The emphasis of this training is placed on education.9 As sensors are placed on the patient's skin, the therapist explains what each sensor will be measuring. For example, the sensors can measure temperature or muscle tension. The patient will be told to do an activity and the therapist will read what the sensor measures and relate it to the patient.10 Patients are then taught how the signals being displayed relate to their physiology. The therapist may say, “Scrunch your face”, and read the muscle tension signal on the screen to point out the patient's physiological responses.9 In essence, the patient is made aware of how the physical activity affects the body.

While biofeedback can address multiple health conditions (Table 3), patients who are suffering from a disease that has a major stress component may also be helped by biofeedback. To make patients aware of how the stress in their lives’ influences physiology, stress management or other psychotherapeutic interventions are used in combination with biofeedback training. This application of biofeedback training has been shown to be quite successful in treating stress related disorders.In the biofeedback element of stress management, patients are told to relax and then engage in a stressful activity (usually a stressful mental activity) and then relax again. In each instance, the therapist can show the patient what their physiological response was in the stressed state and how long it took for the patient to return to baseline (aka the relaxed state). 9 The therapist may give the patients tips or tools to reduce stress in order to maintain in that baseline state as much as possible and reduce the body’s reaction to stressful stimuli. This will ultimately give the patient a feeling of control over their recovery from stress leading to an increased state of wellness. Patients who value self‐control are likely to be most receptive when biofeedback is offered. Two guiding factors toward recommending biofeedback are patients who have medical conditions where stress is a significant component and those who value self-control.5

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is defined as “a state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion”.11 Hypnotizability is defined “an individual’s ability to experience suggested alterations in physiology, sensations, emotions, thoughts, or behavior during hypnosis.”11 The fundamental usefulness of hypnosis in medicine and healing has been controversial for more than 200 years. Does it lead to actual healing properties at the physiologic level or is a therapeutic effect merely the result of an imagined comfort and in the mind only? Nevertheless, in recent years, modern clinical hypnosis has become increasingly popular.

The most clinically significant recent development in medical hypnosis is our understanding that the power of hypnosis resides in the patient and not in the therapist, which implies the existence of useful potential within each patient. The goal of hypnosis is being able to help patients use this unconscious potential. During hypnosis there is an interchange between the therapist and the patient known as a trance. 12 Trance can occur at many levels ranging from rapt attention with eyes open to deep states that resemble somnolence. Hypnotic trance is physiologically a type of waking state and has no relation to the state of sleep. The trance itself is not the treatment, but the trance allows the framework in which the treatment can be effectively carried out.12 In trance states, we sometimes allow our unconscious to solve complex problems or gain a fresh perspective.13 Medical hypnosis is quite different from stage hypnosis. Stage hypnosis is what viewers see in magic shows or portrayed in cinema and it is directly related to commanding a performance. Contrary to this type of hypnosis, medical hypnosis does not suggest outcomes, and in fact the problem may be so complex that its resolution requires total dependence on unconscious processes occurring within the patient.14 Think of hypnosis as activating and further developing what is already within the patient instead of trying to impose from the outside an element that might be unacceptable for that individual’s personality.12

Hypnosis has been shown to be useful in many types of conditions (Table 3). However, hypnosis is most useful when patients have physical or emotional problems that are due at least in part to the patients’ own unconscious limitation of their capacities. Hypnosis is advantageous when treating patients who are not introspective, who are amnesic, or who refuse to consider the psychologic impact of particular events in their lives.12 It is thought that medical hypnosis helps these patients break through their limitations to free their unconscious potential for solving problems.15 Responsiveness to hypnotherapy cannot always be predicted. However, a few conditions typically respond well to hypnotherapy – chronic headache, chronic back pain, chronic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome.5 Obesity and addictions have also been shown to respond to hypnosis although the problems underlying both conditions are usually so complex that seeking a definitive cure through hypnosis or any other single approach is simply not realistic. 12 Hypnosis has been shown to identify underlying issues during trance and remove some stumbling blocks to success in battling obesity and addictions. A successful hypnotist will allow for unconscious obstacles to be removed and in most cases the patient’s condition will naturally improve.12 Regardless of the condition being treated, hypnosis offers an alternative type of treatment even in difficult cases.

Guided Imagery

Guided imagery is a mind-body intervention in which a person imagines and experiences an internal reality in the absence of external stimuli.16 As a mind-body intervention, guided imagery is a mental function that expresses all of the senses to bring about individual changes in behavior, perception or physiologic responses.17 A therapist helps a patient generate mental images that simulate or re-create the perception of sight, sound, taste, smell, movement and touch. Responses to mental images may be similar to that which occurs when the actual stimulus is present.18 The mechanism of action may be related to the power of guided imagery to send messages and information from the brain to the central nervous system and thus connect with physiological processes.19 This intervention represents a basic principle of psychophysiology in that every thought has a physiologic response. When a mental image is experienced, there is an associated emotion connecting that feeling with the mind and body leading to a physiologic change.18 Thus, a guided imagery intervention may decrease perceived stress and associated symptoms leading to a more relaxed state and improvement in both emotional and physical health.

Typically, a therapist using this approach will provide verbal prompts to direct the focus of the imagery, often encouraging the participant to notice various sensory aspects of the scene. Breathing typically becomes slower and more controlled during the process while muscles relax, creating a state of calm and relaxation. Once learned, the technique can also be practiced independently, without the direction of a therapist. Patients can use this tool independently to re-create a sense of calm and peacefulness in times of high anxiety and stress.

Some critics propose that guided imagery does not actually improving the condition or disease itself, but instead reduces the side effects of many conditions and their treatments, such as the nausea, fatigue, anxiety, pain and stress of cancer treatments. Regardless, guided therapeutic imagery is supported by research and it’s been found effective for stress-related, physical, emotional and addiction disorders.5 Various uses of this mind-body therapeutic tool can be viewed in Table 3.

Yoga

Yoga has its roots in Indian philosophy and has been a part of traditional Indian spiritual practice for over 5000 years.20 Traditional yoga is a complex intervention that comprises advice for ethical lifestyle, spiritual practice, physical activity, breathing exercises and meditation.21 While the ultimate goal of traditional yoga has been described as uniting mind, body, and spirit, yoga has become a popular means to promote physical and mental well‐being. Yoga is considered a mind–body approach because of three principal components: meditation (dyana), pranayama (breath regulation), and asanas (postures).20 There are a wide variety of ways yoga can be practiced that range in physical exertion level and primary intention (e.g., increasing self-awareness or examining conduct with self and others).

Yoga is thought to treat the symptoms of certain neurological and psychiatric disorders through a variety of biological mechanisms. The changing of postures in yoga enhance mental health via a variety of mechanisms, which may include stimulating the central nervous system to release endorphins, noradrenaline, serotonin and dopamine.22 The controlled breathing and meditative practices lead to a reduction in sympathetic and an increase in parasympathetic tone.23 Parasympathetic activity is responsible for calming the body’s stress response systems, and is associated with decreased levels of cortisol. Also, some studies have linked the meditative components of yoga to an increase in melatonin.24 Increases in melatonin have been shown to influence various biological mechanisms, including promoting sleep, stimulating the immune system by acting as a powerful antioxidant, and decreasing blood pressure.25 This suggests that aspects of yoga outside of aerobic exercise, such as controlled breathing and meditation techniques, are associated with positive effects on the body. Table 3 lists the current medical uses of yoga with published scientific data. Yoga has also been studied in patients with epilepsy, schizophrenia, migraine, multiple sclerosis, bipolar and post-traumatic stress disorder. 23 Pending more clinical studies, yoga interventions likely will continue to show their benefit as effective adjunctive treatment options for these disorders as well.

Tai Chi

Tai Chi, a form of Chinese low impact mind-body exercise, has been practiced for hundreds of years in the East and is currently gaining popularity in the West. Originally developed for self-defense, Tai chi has the unique feature of combining the exercise of rhythmic movement with a kind of yogic relaxation through deep breathing, self-awareness, and the attempted connecting of mind and body.28 Among the martial arts, this practice is noted for its flowing, slow, dance-like movements, as well as being a vehicle for meditation and spiritual well-being. Since ancient times, Tai Chi practitioners have declared beneficial effects ranging from reduced anxiety, stress, and pain; as well as improved balance, self-awareness and strength. 28 A Harvard University study found that doing Tai Chi helped people maintain strength, flexibility and balance.29 Since, Tai chi is low impact and puts minimal stress on muscles and joints, it may be especially suitable to patients who are physically unable to exercise. See Table 3 for several uses of Tai Chi documented in current medical literature.

Since the link between Tai Chi and health still is quite a new field, especially in the Western world, more research, standardized methods and definitions are needed. We know stress reduction often occurs by engaging in pleasurable activities and whether the positive effects of Tai Chi are due solely to its relaxing, meditative, and exercise aspects, or to more peripheral gains remains to be determined. Tai Chi may be an efficient means of stress reduction for people who successfully learn the art and who enjoy its philosophical, martial and mental aspects.28

| Table 3. Mind-Body Therapy in Clinical Conditions5,9,12,26,27,30 |

| Mind-body therapy |

Condition/Disease |

| Biofeedback |

Chronic constipation, hypertension, fecal incontinence, urinary incontinence, insomnia, migraine headache, Raynaud phenomenon (primary), tension headache, anxiety, attention deficit disorder, chronic pain, epilepsy, motion sickness |

| Hypnosis |

Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting, chronic pain, insomnia, irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, phobias, panic attacks |

| Guided Imagery |

Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting, chronic pain, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, migraine headache, tension headache, anxiety, stress, depression |

| Yoga |

Chronic pain, anxiety, depression |

| Tai Chi |

Arthritis, anxiety, depression |

Qigong

Qigong is an integrated mind-body healing method that has been practiced in China for thousands of years. The Chinese have long treasured qigong for its effectiveness both in healing and in preventing disease. Qigong is the study and practice of cultivating vital life-force through various techniques including postures, meditations, guided imagery and specific breathing techniques.31 Qi means "breath" or "air" and is considered the "vital-life-force”. Gong means "work" or "effort" and refers to the commitment to any practice or skill. 32 Through this practice, the individual aims to develop the ability to manipulate breath in order to promote self-healing, prevent disease, and increase longevity. Medical qigong is the oldest of the four branches of Traditional Chinese Medicine and is the foundation from which acupuncture, herbal medicine and Chinese massage originated.31

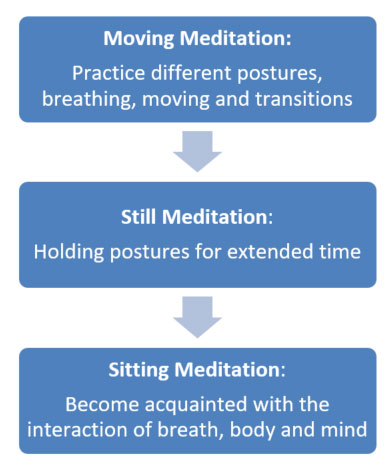

According to the traditional teachings of qigong, there are three types of meditations that are involved.32 Figure 1 depicts the energetic flow of qigong practice.

Figure 1. Qigong Meditations32

Moving, still, and sitting meditations can all be practiced with or without visualization. Visualization enhances the scope of practice by allowing the practitioner to guide the energy in accordance with the visualization.32

Qigong healers practice the same foundational techniques as everyone else but have gained a deeper understanding of the techniques that allow them to pass along healing to others. They use a number of different modalities including massage, acupuncture, energized stones, and the placing of hands to promote healing.32 Qigong uses combinations of these practices in an effort to help treat cancer, immune system disorders, improve digestion, relieve headaches, sinus congestion, pain and stress.31 The most critical issue confronting the use of qigong as a health therapy in western medicine remains to be the lack of scientific evidence. Few studies have been published in English and often Chinese studies are difficult to obtain and translate. Funding and support to conduct high quality research may prove that qigong has a significant place in traditional modern medicine.

Meditation/Mindfulness

Meditation and related contemplative practices involve various methods to self-regulate attention and have been used for centuries to achieve states of emotional calm and self-understanding. While meditative practices are often derived from various spiritual traditions, they can be used without a religious context, and they are increasingly being used within health care settings to address mental and physical health conditions. Jon Kabat-Zinn, Ph.D. is credited as pioneering the research focused on mind-body interactions for healing and on the clinical applications of mindfulness meditation. In the words of Jon Kabat-Zinn, mindfulness is “the awareness that arises through paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.”33By focusing on the breath, the idea is to cultivate attention on the body and mind as it is moment to moment, and in doing so help with pain, both physical and emotional. In 1979, Dr. Kabat-Zinn recruited chronically ill patients not responding well to traditional treatments to participate in his newly formed eight-week stress-reduction program, which we now call Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).33 Since then, substantial research has mounted demonstrating how mindfulness-based interventions improve both mental and physical health.

There are three well-studied mindfulness-based interventions used today including MBSR, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), and mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP). These practices are based on the principle that awareness of environmental cues and internal phenomena, lead one to an increased awareness that will allow for interpretation and if necessary, change in a habitual response. 34 In other words, mindfulness-based treatments teach you to remain in contact with and relate differently to challenging affective or physical states. Table 4 outlines the differences between each type of mindfulness-

| Table 4. Mindfulness-Based Therapies33,35,36,37 |

| Therapy |

Description |

| Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) |

• Enables patients to learn skills that prevent the recurrence of depression

• Enables patients to become aware of bodily sensations, thoughts, and feelings associated with depressive relapse and to relate constructively to these experiences

• Therapists provide skills to help formulate adaptive responses to triggers associated with depressive relapse |

| Mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP) |

• Enables patients to learn the skills that prevent substance use relapse

• Enables patients to identify individual risk factors and common antecedents of relapse

• Best suited to individuals who have undergone initial treatment and wish to develop a lifestyle that supports recovery |

| Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) |

• Focuses on mind and body awareness to reduce the physiological effects of stress, pain or illness

• Enables patients to become aware of habitual reactions and develop less emotional reactivity to internal and external cues |

Numerous reviews have been conducted to examine the efficacy of mindfulness-based therapies suggesting that they are effective for reducing the distress associated with physical or psychosomatic illnesses. Table 5 lists the medical uses that have documented scientific evidence in clinical studies.

| Table 5. Mindfulness-Based Therapies in Clinical Conditions35,36,37,38 |

| Disorder/Disease |

| Anxiety |

| Depression |

| Binge eating disorder |

| Substance use disorder |

Mindfulness Practices for Self-Care

We have discussed three well-studied mindfulness-based interventions used in clinical practice that require a therapist who has been trained to deliver these types of therapies. However, now it is time to focus on things you can do in your own practice that will allow you to promote self-care. Practicing mindfulness exercises can help direct attention away from draining thoughts and perhaps lead to less stress, anxiety and depressive ways of thinking. There are many simple ways to practice mindfulness that can be applied in your daily life. The following are two examples that can be utilized to promote self-awareness and improve overall health and well-being.

Keep a journal of your emotions and the behaviors that followed. When you journal do not simply record your activities for the day. Rather, focus on your emotional reactions to events that occurred and your response to these events (behaviors). Look for patterns to these reactions. You might find patterns with patients, friends or family members. The following are some questions that might help stimulate your writing.39

- What were the most memorable things that happened today (positive and negative)? What emotions were you feeling and what behavior was elicited as a result.

- Did you learn anything new about your self today? How will you apply the new knowledge?

- Describe how one of your emotions led to a behavior you were not previously aware of.

- In what ways would you like to change any of your behaviors if you could?

Doing a meditation exercise can also help you focus on your emotions. Meditate on interactions, both rewarding and difficult, with peers, patients, clinical circumstances, or in your personal life. The following describes a simple meditation exercise that can be practiced daily.39

- Find a quiet room, sit on a chair or cross-legged on a pillow on the floor.

- Close your eyes and pay attention to your breathing. As you focus on each breath, breathe normally and say to yourself “in” and “out” as you inhale and exhale.

- Continue to focus on your breathing as you try to

- As you do this, your mind may wander. It is ok to let this happen. When this happens simply return the focus back to your abdomen and breathing in and out.

When you start meditating try this for no longer than 10 minutes at first. Perhaps try this at your next meeting or when you are feeling anxious in a particularly stressful situation.

Conclusion

Mind-body complementary health approaches are a diverse group of health care practices focused on the relationships between the mind, body, brain and behavior. A variety of techniques including yoga, biofeedback, meditation, tai chi, qigong, hypnosis and guided imagery are designed to enhance the mind’s capacity to affect bodily function and symptoms that promote a positive overall state of health and well-being. As a stand-alone therapy or as adjunct treatment with other forms of traditional medicine, mind-body medicine has shown favorable effects in many chronic disease states.

Today, most patients want to be seen and treated as a whole person, not as a disease. In order to do this, a patient must be viewed as someone whose being has physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions and practicing mind-body medicine allows the emphasis to be placed on a holistic and unitary view of mind, body, and spirit. Ignoring any of these aspects leaves the patient feeling incomplete and may even interfere with the therapeutic process. In addition, mind-body therapies offer the psychological benefit of increasing a sense of control for the patient. On a day-to-day basis, the patient oversees his or her own health, and the daily decisions people make have a huge impact on the treatment outcomes and quality of life. Looking at the patient from a holistic approach allows the clinician to consider the emotional, mental, social, spiritual, experiential and behavioral factors that can directly affect health on a daily basis. This type of integrative practice will continue to increase in popularity as some of the more conventional mind-body practices are now established, supported by evidence, have a favorable safety profile and are widely available.

REFERENCES

- Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Black LI, et al. Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among U.S. adults aged 18 and over. NCHS Data Brief, no 325. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

- Purohit MP, Wells RE, Zafonte RD, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and the use of complementary and alternative medicine. PM R. 2013;5(1):24-31.

- NCCAM (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine). Expanding Horizons of Healthcare: Five-Year Strategic Plan 2001-2005.Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. NIH Publication No. 01-5001.

- Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(12):1-23.

- Mehta D. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. Mind-Body Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2021.

- Nakagawa-Kogan, H. Self-management training: potential for primary care. Nurse Practitioners Forum. 1994;5(2):77-84.

- Massey J. Mind body medicine: its history and evolution. Naturopathic Doctor News and Reviews. 2015;11(6):1-5.

- Kesić S. Systems biology, emergence and antireductionism. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2016;23(5):584-591.

- Frank DL, Khorshid L, Kiffer JF, et al. Biofeedback in medicine: who, when, why and how? Ment Health Fam Med. 2010;7(2):85-91.

- Schwartz MS, Andrasik F. Biofeedback: A Practitioner's Guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2003.

- Elkins GR, Barabasz AF, Council JR, et al. Advancing research and practice: the revised APA division 30 definition of hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn. 2015;57(4):378–85.

- Alman B. Medical hypnosis: an underutilized treatment approach. Perm J. 2001;5(4):35-40.

- Rossi EL. The Psychobiology of Mind-Body Healing: New Concepts of Therapeutic Hypnosis. Revised ed. New York: NY: Norton; 1993:40–6.

- Wester WC, Smith AH., Jr. Clinical Hypnosis: A Multidisciplinary Approach.Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott;1984:7–17.

- Lankton SR, Lankton CH. The Answer Within: Clinical Framework of Ericksonian Hypnotherapy.New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1983:7–15.

- Menzies V, Taylor AG. The idea of imagination: an analysis of ‘imagery’. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine. 2004;20(2):4–10.

- Freeman L. Mosby’s Complementary & Medicine: A Research-Based Approach.3rd ed. Mosby Elsevier; St. Louis, MO: 2009.

- Menzies V, Jallo N. Guided imagery as a treatment option for fatigue: a literature review. J Holist Nurs. 2011;29(4):279-286.

- Schaub B, Burt M. Holistic Nursing: A Handbook for Practice (7th ed). Burlington, Mass; Jones and Bartlett Learning: 2015.

- Feuerstein G. The Yoga Tradition. Hohm Press; Prescott, AZ: 1998.

- Yogi H. Hatha Yoga Pradipida. Miramar, FL: Nada Productions, Inc.: 2006.

- Syvalahti EK. Biological aspects of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994;377:11-15.

- Meyer HB, Katsman A, Scones AC, et al. Yoga as an ancillary treatment for neurological and psychiatric disorders: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24:152-164.

- Tooley GA, Armstrong SM, Norman TR, et al. Acute increases in night-time plasma melatonin levels following a period of meditation. Biol Psychol. 2000; 53:69–78.

- Kitajima T, Kanbayashi T, Saitoh Y, et al. The effects of oral melatonin on the autonomic function in healthy subjects. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001; 55:299–300.

- Bussing A, Ostermann T, Ludtke R, et al. Effects of yoga interventions on pain and pain-associated disability: a meta-analysis. J Pain. 2012;13:1-9.

- Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21-35.

- Sandlund ES, Norlander T. The effects of tai chi chuan relaxation and exercise on stress responses and well-being: an overview of research. Int J Strss Mgmt. 2000;7:139–149.

- Audette JF, Jin YS, Newcomer R, et al. Tai Chi versus brisk walking in elderly women. Age and Ageing. 2006;35(4):388-393.

- Wang C, Bannuru R, Ramel J, et val. Tai Chi on psychological well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:23.

- Cohen, KS. The Way of Qigong: The Art and Science of Chinese Energy Healing. The Random House Publishing Group; New York, NY:1997.

- Johnson, JA. Chinese Medical Qigong Therapy: A Comprehensive Clinical Text. Pacific Grove, Calif.; International Institute of Medical Qigong:2000.

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness mediation. Piatkus; London, England:2013.

- Witkiewitz K, Bowen S. Depression, craving, and substance use following a randomized trial of mindfulness-based relapse prevention. J Consult Clin Psychol.2010;78(3):362–374.

- Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet2015;386(9988):63–73.

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression (2nd ed). Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013.

- Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, et al. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):547-556.

- Kristeller JL, Hallett CB. An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. J Health Psychol. 1999;4(3):357-63.

- Smith RC, Osborn GG, Dwamena FC, et al. Essentials of Psychiatry in Primary Care: Behavioral Health in the Medical Setting. Enhancing Your Own Personal Care. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY:2019.

Back to Top