Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Combination Therapy with Insulins and GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

INTRODUCTION

As of 2014, an estimated 29.1 million people in the United States (U.S.) have diabetes.

Unfortunately, approximately one-third of these people remain undiagnosed.1 New cases of diabetes

are being diagnosed at an alarming rate, with the majority of cases being diagnosed in adults over the

age of 45 years. Annual direct medical costs related to diabetes in the U.S. exceed $175 billion and

indirect costs total approximately $70 billion.1 Patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) are typically

overweight or obese and agents that are commonly used in the treatment of T2DM, such as

sulfonylureas and insulin, can cause further weight gain. This article will review evidence supporting the

use of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, a class of agents known to cause weight loss, in

combination with insulin for the treatment of T2DM.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF T2DM

The pathophysiology of T2DM is multifactorial, but insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction

are the primary defects.2,3 Insulin resistance is evident in the liver as hepatic glucose production that

remains elevated despite elevated insulin concentrations. In the peripheral tissues, insulin resistance is

evident as endogenous insulin that is not able to facilitate glucose uptake into the peripheral tissues.

Beta-cell dysfunction results from the inability of beta-cells to compensate for insulin resistance and the

resultant hyperglycemia is toxic to the cells. Inappropriate glucagon release is also present in patients

with T2DM. Glucagon regulates the rate of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis to maintain glucose

homeostasis. In patients with T2DM, exogenous insulin is unable to suppress glucagon release, which

results in further hyperglycemia.2,3

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS IN T2DM

Unless contraindications exist, all patients should be initiated on metformin and lifestyle

interventions at the time of diagnosis with T2DM.4,5 Metformin is considered first-line therapy due to its

proven efficacy, as well as its low cost, general tolerability, low risk of hypoglycemia, neutral/beneficial

effects on weight, and cardiovascular benefits. If metformin is not an option, the American Diabetes

Association (ADA) guidelines recommend any of the following classes of agents for first-line treatment,

in no preferential order: sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones (TZDs), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4)

inhibitors, sodium glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, or basal insulin.4 In contrast, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) guidelines recommend the use

of the following agents, in order of preference: GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, DPP-4

inhibitors, TZDs, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, sulfonylureas, or meglitinides.5 The ADA recommends

initial therapy with 2 agents in patients with a baseline hemoglobin A1c (A1c) of 9% or higher, and

patients presenting with a baseline A1c of at least 10% to 12% should be initiated on basal insulin plus

mealtime insulin or a GLP-1 receptor agonist.4 The AACE recommends a more aggressive treatment

approach, with dual therapy recommended for patients with a baseline A1c of 7.5% or higher and dual

therapy, triple therapy, or insulin with or without other agents when the baseline A1c is greater than

9%.5

After 3 months of treatment with the initial agent, if the A1c remains above goal, a second agent

should be added.4,5 Medications with different mechanisms of action for dual therapy and triple therapy

should be chosen in order to target the various defects present in T2DM. The ADA recommends that a

sulfonylurea, TZD, DPP-4 inhibitor, SGLT2 inhibitor, GLP-1 receptor agonist, or basal insulin be added to metformin for dual therapy.4 The AACE recommends, in order of preference, a GLP-1 receptor agonist,

SGLT2 inhibitor, DPP-4 inhibitor, TZD, basal insulin, colesevelam, bromocriptine, alpha-glucosidase

inhibitor, sulfonylurea, or meglitinide as add-on therapy to metformin.5 In general, the addition of a

second agent will decrease the A1c no more than 1%. Insulin offers the most substantial lowering of

A1c. Therefore, the higher the A1c, the more likely that treatment with insulin will be necessary.4 If the

A1c goal is not met after 3 months with dual therapy, a third agent should be added. If the A1c remains

above goal after 3 months of triple therapy, insulin should be initiated or the existing insulin regimen

should be intensified.4,5 The first insulin chosen should be a basal insulin. However, if basal insulin has

already been initiated, prandial insulin or a GLP-1 receptor agonist should be added.4,5 The benefits of

adding a GLP-1 receptor agonist instead of prandial insulin include weight loss, a lower risk of

hypoglycemia, and a simpler dosing regimen.4 According to the AACE guidelines, the addition of an

SGLT2 inhibitor or a DPP-4 inhibitor may also be considered at this step.5

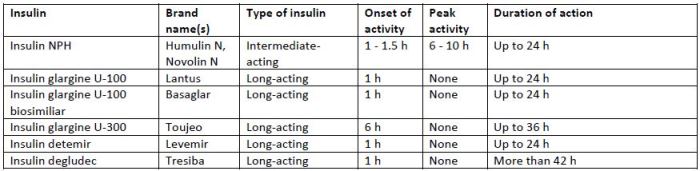

Basal insulins are categorized as intermediate-acting or long-acting insulins. Table 1 lists the

characteristics of the basal insulins currently on the market in the U.S.6 Basal insulin is initiated at 10

units daily or 0.1 to 0.2 units/kg/day and titrated on the basis of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels.4

| Table 1. Characteristics of currently available basal insulin products6 |

|

| Abbreviations: NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn |

TARGETING POSTPRANDIAL GLUCOSE LEVELS

FPG and A1c levels are traditionally used to assess diabetes control. However, evidence exists to

support the importance of postprandial glucose (PPG) as a treatment target. PPG excursions, defined as

2-hour glucose levels above 180 mg/dL, should be suspected when the FPG is normal but the A1c

remains elevated.4 PPG excursions are a significant factor in glycemic control, especially when the A1c

falls below 8.4%. Results from the DECODE trial and the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project

revealed that post-load (i.e., after an oral glucose tolerance test) blood glucose levels were a better

predictor of cardiovascular mortality than FPG.7,8 In addition, data from the Diabetes Intervention Study

showed that PPG, not FPG, significantly increased the risk of myocardial infarction and death.9

Agents that significantly reduce PPG levels include GLP-1 receptor agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors,

alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, sulfonylureas, meglitinides, short-acting and rapid-acting insulins, and

pramlintide.10 The GLP-1 receptor agonists are classified as either short-acting or long-acting agents.

Short-acting agents include lixisenatide and twice-daily exenatide; dulaglutide, exenatide long-acting

release (LAR), liraglutide, semaglutide, and albiglutide are long-acting agents. The short-acting GLP-1

receptor agonists have a more pronounced effect on gastric emptying and, therefore, reduce PPG to a

greater extent than the long-acting agents.11

GLP-1 receptor agonists

The GLP-1 receptor agonists are long-acting analogues of native GLP-1, an incretin hormone

released by the gut. Active GLP-1 plays a role in glucose homeostasis by decreasing glucagon release,

increasing glucose-dependent insulin synthesis and secretion, and improving beta-cell function. GLP-1

also decreases gastric emptying, increases satiety, and decreases food intake.12 Currently, there are 5

GLP-1 receptor agonists on the market in the U.S.: exenatide (Byetta), exenatide LAR (Bydureon),

liraglutide (Victoza), albiglutide (Tanzeum), and dulaglutide (Trulicity). Two additional agents are

currently under development: semaglutide, which is in phase III clinical trials, and lixisenatide, which is

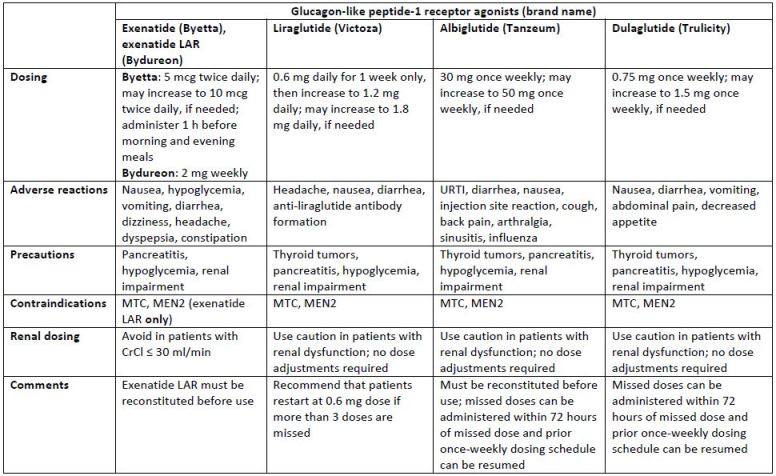

under final review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Dosing information for each of the

available agents is listed in Table 2. All of the agents can be administered any time of the day, without regard to meals, with the exception of the exenatide twice-daily formulation, which should be

administered 60 minutes before meals.13-17 GLP-1 receptor agonists should be injected subcutaneously

into the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm. GLP-1 receptor agonists are only approved for use in T2DM.

| Table 2. Dosing guidelines and safety considerations for currently available glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists13-17 |

|

| Abbreviations: CrCl, creatinine clearance; LAR, long-acting release; MEN2, multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2; MTC, medullary thyroid carcinoma; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection |

Although the A1c reduction is similar between short-acting and long-acting GLP-1 receptor

agonists, the mechanisms by which they lower A1c are slightly different. Short-acting GLP-1 receptor

agonists have less of an effect on FPG and more of an effect on PPG than long-acting agents; long-acting

agents primarily affect FPG. A recent review of head-to-head clinical trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists

showed significant differences in weight loss among agents.18 In trials that compared a short-acting

agent to a long-acting agent, long-acting agents produced significantly more weight loss. Of the short-acting agents, twice-daily exenatide led to significantly more weight loss than lixisenatide.19 Head-to-head trials comparing long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists showed that liraglutide caused significantly

more weight loss than exenatide LAR,20 albiglutide,21 and dulaglutide.22 Common adverse effects,

reported in at least 5% of patients, for the GLP-1 receptor agonists are summarized in Table 2.

Similarities among the adverse effects of the agents include diarrhea and nausea.13-17 Patients should be

warned that nausea has been reported in up to 40% of patients but that it does subside over time for

most patients. The incidence of nausea is similar with short-acting and long-acting agents, but nausea

appears to improve faster in patients using the long-acting agents.11

The package inserts for the GLP-1 receptor agonists, with the exception of immediate-release

exenatide, contain black box warnings concerning the risk of thyroid c-cell tumors. This concern arose

from animal data; it is unknown whether GLP-1 receptor agonists cause these tumors in humans.

Nonetheless, use of these agents is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of

medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. Patients should be

educated about this risk and counseled regarding symptoms of thyroid tumors, which include a mass in

the neck, dysphagia, dyspnea, and persistent hoarseness.14-17 Postmarketing reports of pancreatitis have

been associated with GLP-1 receptor agonist use, and clinicians should monitor patients for signs and

symptoms of pancreatitis after initiation or dose increases of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Patients should

be educated to seek medical help immediately if they experience persistent, severe abdominal pain, as

this is a warning sign for pancreatitis.13-17 Each of the GLP-1 receptor agonists are being monitored under

an FDA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program; fact sheets for each agent can be found on the

FDA website.

Other precautions and warnings to consider before initiating a GLP-1 receptor agonist include

renal impairment and severe gastrointestinal (GI) disease. Postmarketing reports of acute renal failure

and worsening of chronic renal failure have been associated with GLP-1 receptor agonist use. Many of

these events occurred in patients who reported severe GI adverse reactions including nausea, vomiting,

diarrhea, and dehydration. Clinicians should consider monitoring renal function with the initiation and

dose escalation of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Renal function should be closely monitored in patients

complaining of severe GI adverse reactions.13-17 Since GLP-1 receptor agonists affect gastric emptying,

these agents should be avoided in patients with severe GI disease. However, none of the agents have

been studied in such patients.13-17

Combinations of GLP-1 receptor agonists and insulin

Studies have shown that combining a GLP-1 receptor agonist with insulin improves glycemic

control and causes weight loss. Further, by combining these agents, patients are often able to decrease daily insulin requirements, which not only reduces weight gain but also affords the patient a simpler

dosing regimen. The package inserts for the GLP-1 receptor agonists warn clinicians to exercise caution

when combining these agents with insulin due to the potential for severe hypoglycemia. However, little

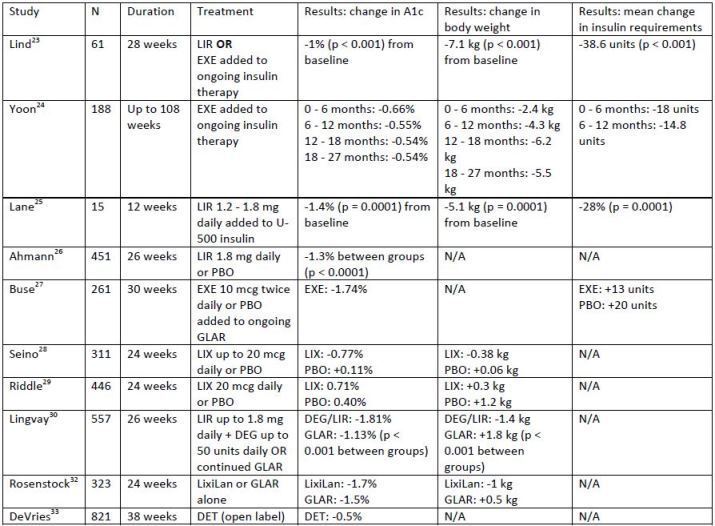

to no hypoglycemia has been reported in studies of combination therapy. Table 3 summarizes the

evidence supporting the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in combination with insulin.

| Table 3. Summary of clinical trials of combined glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and insulin |

|

| Abbreviations: ALB, albiglutide; ASP, insulin aspart; DEG, insulin degludec; DET, insulin detemir; EXE, exenatide; GLAR, insulin glargine; LIR, liraglutide; LIS, insulin lispro; LIX, lixisenatide; LixiLan, lixisenatide + insulin glargine; NON-DET, non-detemir-treated patients; PBO, placebo |

Several studies have examined the effect of adding a GLP-1 receptor agonist to an existing

insulin regimen in patients with T2DM. In one study, the addition of liraglutide or twice-daily exenatide

in patients using various insulin regimens (multiple daily injections, basal only, or premixed) resulted in a

mean A1c reduction of 1% and an average weight loss of 7.1 kg (p < 0.001 for both assessments).23 Also,

patients were able to significantly decrease their daily insulin requirements by an average of 38.6 units.

A retrospective study examined the effect of twice-daily exenatide on glycemic control, weight, and

insulin dose.24 Similar to the previous study, patients in this study were on various insulin regimens. The

mean decreases in A1c and weight were significant at each time period reported. Total daily doses of

insulin were not significantly reduced, but, when prandial insulin doses were examined separately, it

was discovered that exenatide led to significant decreases in prandial insulin doses at all time periods.

An observational study examined the effect of adding liraglutide to patients currently using U-500

insulin.25 This study involved 15 obese patients who were using an average of 192 units of U-500 insulin

daily. Liraglutide (up to 1.8 mg daily) use resulted in a 1.4% reduction in A1c (p = 0.0001). In addition,

weight decreased by an average of 5.1 kg and insulin doses decreased by approximately 28% (p = 0.0001

for both assessments).

The addition of a GLP-1 receptor agonist to patients on basal insulin only (with or without oral

agents) has been examined in several studies. When liraglutide was added to patients inadequately

controlled on basal insulin, patients experienced an average A1c decrease of 1.3% compared to placebo

(p < 0.001).26 Weight decreased significantly more in the liraglutide group with a between-group

difference of approximately 3.1 kg (p < 0.001). A study investigating the use of twice-daily exenatide

added to insulin glargine revealed a 0.7% reduction in A1c compared to placebo (p < 0.001).27 Although

insulin doses increased in both groups, they increased less in the group receiving concomitant exenatide

than in the insulin glargine-only group (13 units and 20 units, respectively). Also, patients in the

exenatide group experienced weight loss while those in the placebo group gained weight. Two studies

examined the effect of adding lixisenatide to patients on basal insulin.28,29 The results of one of these

studies showed a decrease in A1c of 0.71% with lixisenatide and 0.4% with placebo (p < 0.001). PPG was

also significantly decreased in the lixisenatide group compared to the placebo group, and significantly

more patients taking lixisenatide achieved an A1c of less than 7%.29 Similarly, the second study found a

mean difference in A1c lowering of 0.88% with lixisenatide compared to placebo (p < 0.001).28 Lixisenatide use also significantly improved PPG and FPG compared to placebo.

Lingvay et al30 examined the effect of a fixed-dose combination of liraglutide plus insulin

degludec (basal insulin) versus continuing insulin glargine alone. Mean A1c decreased by 1.81% in the

insulin degludec/liraglutide group and by 1.13% in the insulin glargine group. These results showed that

insulin degludec/liraglutide was superior to insulin glargine alone (p < 0.001). Body weight decreased by 1.4 kg in the insulin degludec/liraglutide group and increased by 1.8 kg in the insulin glargine group (p <

0.001). The results of this trial were similar to those reported in a pooled analysis of 5 other studies

evaluating the use of insulin degludec plus liraglutide.31 The analysis found the combination to be non-inferior (and, in some cases, superior) to up-titration of basal insulin or basal/bolus insulin regimens and resulted in less hypoglycemia and weight gain in patients with T2DM. Another study examining the

effect of a fixed-dose combination of a GLP-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin compared lixisenatide

plus insulin glargine (LixiLan) to insulin glargine alone.32 The mean A1c decreased by 1.7% in the LixiLan

group and by 1.5% in the insulin glargine group. These results showed LixiLan was superior to insulin

glargine alone (p = 0.01). Improvements in body weight and PPG were also significant in the LixiLan

group compared to insulin glargine alone (p < 0.001 for both assessments).

DeVries and colleagues33 examined the effect of adding liraglutide to insulin-naïve patients on

metformin (with or without a sulfonylurea); basal insulin was added if further treatment was required.

After a 12-week run-in period with liraglutide, patients were randomized to receive open-label insulin

detemir or no additional insulin for 26 weeks. Following randomization, the addition of insulin detemir

led to a significant reduction in A1c of 0.5%; patients not using insulin detemir experienced an A1c

increase of 0.02% (p < 0.001). Mean body weight decreased by 0.16 kg in patients who required

additional insulin and by 0.95 kg in patients who did not require additional insulin. This study is the first

to examine the effect of adding insulin to a GLP-1 receptor agonist versus adding a GLP-1 receptor

agonist to an existing insulin regimen.

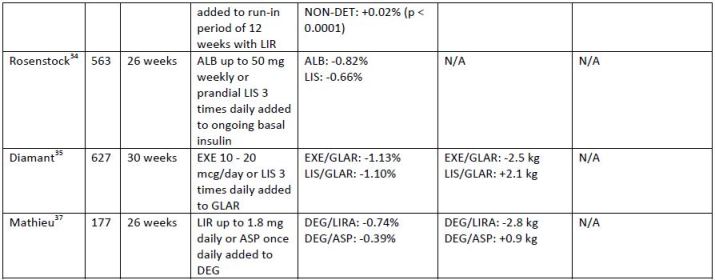

The addition of a GLP-1 receptor agonist compared to prandial insulin in patients not controlled

on basal insulin has been evaluated in several studies. In a study comparing albiglutide to 3-times-daily

prandial insulin (insulin lispro), A1c decreased by 0.82% in the albiglutide group and by 0.66% in the

insulin lispro group.34 The treatment difference between albiglutide and insulin lispro met non-inferiority criteria for albiglutide compared to insulin lispro. Weight decreased from baseline in the

albiglutide group and increased in the insulin lispro group, with a between-group difference of -1.5 kg (p

< 0.001). Hypoglycemia was twice as common in the insulin lispro group. A similar study compared the

effects of adding twice-daily exenatide to 3-times-daily insulin lispro in patients uncontrolled on basal

insulin.35 After 30 weeks, the between-group difference in A1c was found to be non-inferior for

exenatide compared to insulin lispro. In addition, significant improvements in weight and FPG were

experienced by patients in the exenatide group (p < 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively). Lixisenatide once

daily was compared to insulin glulisine 1 or 3 times daily added to basal insulin in a 26-week trial.36 Results of this trial were similar to the aforementioned trials, and, in terms of A1c improvement, the

addition of lixisenatide was non-inferior to the addition of insulin glulisine 1 or 3 times daily. In addition,

lixisenatide was superior to 3-times-daily insulin glulisine for changes in body weight. Finally, the

addition of liraglutide was compared to a single daily dose of insulin aspart in patients uncontrolled on

insulin degludec.37 A1c improved significantly more in the group using liraglutide than in the group using

insulin aspart, with a between-group difference of 0.32% (p = 0.0024). Weight loss was also significantly

greater in the liraglutide group, with a between-group difference of 3.75 kg (p < 0.001).

MEDICATIONS CURRENTLY IN DEVELOPMENT THAT TARGET PPG

Lixisenatide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist currently approved in Europe as Lyxumia; it is under

review by the FDA for approval in the U.S. Lixisenatide is administered once daily, 60 minutes before a

meal.38 Considering the European prescribing information, lixisenatide is likely to have the same

warnings and precautions as the other GLP-1 receptor agonists. Sanofi expects a response from the FDA

regarding lixisenatide approval in July 2016.39

Combination products that include a basal insulin and a GLP-1 receptor agonist are currently

under development. Sanofi has submitted a new drug application for a combination product including insulin glargine and lixisenatide.39 Novo Nordisk's combination product, Xultophy, contains insulin

degludec and liraglutide; it is currently approved in Europe and is awaiting approval by the FDA in the

U.S.40 Both combination products have been recommended for approval by an FDA Advisory Panel.41,42 Combination products such as these would improve patient adherence due to simple dosing regimens.

SUMMARY

T2DM is a significant contributor to increasing health care costs in the U.S. With adequate

control of glucose levels, complications associated with diabetes can be reduced. GLP-1 receptor

agonists are safe and effective for controlling blood glucose levels and treating T2DM. These agents are

also fairly well tolerated: GI effects are the most common adverse effects, but these symptoms abate

over time. Safety concerns, including the risks of thyroid cancer and pancreatitis, should be considered

before initiating a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Despite the warning found in the package labeling, clinical

evidence supports the use of combining a GLP-1 receptor agonist with basal insulin. Recently, published

guidelines for the treatment of diabetes have changed to reflect the role of this combination. Further,

the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists is now considered an alternative to preprandial insulin, a former

mainstay of diabetes therapy. The combination of GLP-1 receptor agonists and basal insulin offers

patients a simple dosing regimen, weight reduction, and glycemic control of both FPG and PPG levels.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed

March 24, 2016.

2. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2016. Diabetes Care.

2016;39(Suppl. 1):S1-112.

3. Aronoff SL, Berkowitz K, Shreiner B, Want L. Glucose metabolism and regulation: beyond insulin

and glucagon. Diabetes Spectr. 2004;17(3):183-190.

4. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes,

2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes

Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):

140-149.

5. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association

of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2

diabetes management algorithm - 2016 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(1):84-113.

6. Lacy C, Armstrong L, Ingrim N, Lance L, eds. Drug Information Handbook. 25th ed. Cleveland, OH:

Lexicomp Inc; 2016.

7. DECODE Study Group, the European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Glucose tolerance and

cardiovascular mortality: comparison of fasting and 2-hour diagnostic criteria. Arch Intern Med.

2001;161(3):397-405.

8. Lowe LP, Liu K, Greenland P, et al. Diabetes, asymptomatic hyperglycemia, and 22-year mortality

in black and white men: the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(2):163-169.

9. Hanefeld M, Fischer S, Julius U, et al. Risk factors for myocardial infarction and death in newly

detected NIDDM: the Diabetes Intervention Study, 11-year follow-up. Diabetologia.

1996;39(12):1577-1583.

10. Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical

Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology - clinical practice guidelines for

developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan - 2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(Suppl 1):1-87.

11. Giorgino F, Bonadonna RC, Gentile S, et al. Treatment intensification in patients with inadequate

glycemic control on basal insulin: rationale and clinical evidence for the use of short-acting and

other glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016.

12. Weber AE. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors for the treatment of diabetes. J Med Chem.

2004;47(17):4135-4141.

13. Byetta [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

14. Tanzeum [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: GlaxoSmithKline; 2015.

15. Bydureon [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

16. Trulicity [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly; 2015.

17. Victoza [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2015.

18. Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Ellis SL. GLP-1 receptor agonists: a review of head-to-head clinical studies.

Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2015;6(1):19-28.

19. Rosenstock J, Raccah D, Koranyi L, et al. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once daily versus

exenatide twice daily in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin: a 24-week,

randomized, open-label, active-controlled study (GetGoal-X). Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):2945-2951.

20. Buse J, Nauck M, Forst T, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients

with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-6): a randomized, open-label study. Lancet.

2013;381(9861):117-124.

21. Pratley R, Nauck M, Barnett A, et al. Once-weekly albiglutide versus once-daily liraglutide in

patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral drugs (HARMONY 7): a

randomized, open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority phase 3 study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.

2014;2(4):289-297.

22. Dungan K, Povedano S, Forst T, et al. Once-weekly dulaglutide versus once-daily liraglutide in

metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD-6): a randomized, open-label, phase

3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1349-1357.

23. Lind M, Jendle J, Torffvit O, Lager I. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogue combined with

insulin reduces HbA1c and weight with low risk of hypoglycemia and high treatment satisfaction. Primary Care Diabetes. 2012;6(1):41-46.

24. Yoon N, Cavaghan M, Brunelle R, Roach P. Exenatide added to insulin therapy: a retrospective

review of clinical practice over two years in an academic endocrinology outpatient setting. Clin

Ther. 2009;31(7):1511-1523.

25. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J. The effect of liraglutide added to U-500 insulin in patients with

type 2 diabetes and high insulin requirements. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(5):592-595.

26. Ahmann A, Rodbard H, Rosenstock J, et al. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus placebo

added to basal insulin analogues (with or without metformin) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a

randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(11):1056-1064.

27. Buse J, Bergenstal R, Glass L, et al. Use of twice-daily exenatide in basal insulin-treated patients

with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):103-112.

28. Seino, Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of

the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes

insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):910-917.

29. Riddle MC, Forst T, Aronson R, et al. Adding once-daily lixisenatide for type 2 diabetes

inadequately controlled with newly initiated and continuously titrated basal insulin glargine: a

24-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study (GetGoal-Duo 1). Diabetes Care.

2013;36(9):2497-2503.

30. Lingvay I, Manghi F, Garcia-Hernandez P, et al. Effect of insulin glargine up-titration vs insulin

degludec/liraglutide on glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with uncontrolled type 2

diabetes: the DUAL V randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(9):898-907.

31. Freemantle N, Mamdani M, Vilsboll T, et al. IDegLira versus alternative intensification strategies

in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin therapy. Diabetes Ther.

2015;6(4):573-591.

32. Rosenstock J, Diamant M, Aroda VR, et al. Efficacy and safety of LixiLan, a titratable fixed-ration

combination of lixisenatide and insulin glargine, versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes

inadequately controlled on metformin monotherapy: the LixiLan proof-of-concept randomized

trial. Diabetes Care. 2016.

33. DeVries JH, Bain S, Rodbard H, et al. Sequential intensification of metformin treatment in type 2

diabetes with liraglutide followed by randomized addition of basal insulin prompted by A1c

targets. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1446-1454.

34. Rosenstock J, Fonseca V, Gross J, et al. Advancing basal insulin replacement in type 2 diabetes

inadequately controlled with insulin glargine plus oral agents: a comparison of adding

albiglutide, a weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist, versus thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro. Diabetes

Care. 2014;37(8):2317-2325.

35. Diamant M, Nauck MA, Shaginian R, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist or bolus

insulin with optimized basal insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(10):2763-2773.

36. Rosenstock J, Guerci B, Hanefeld M, et al. Prandial options to advance basal insulin glargine

therapy: testing lixisenatide plus basal insulin versus insulin glulisine either as basal-plus or

basal-bolus in type 2 diabetes: the GetGoal Duo-2 trial. Diabetes Care. 2016.

37. Mathieu C, Rodbard HW, Cariou B, et al. A comparison of adding liraglutide versus a single daily

dose of insulin aspart to insulin degludec in subjects with type 2 diabetes (BEGIN: VICTOZA ADD-ON). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(7):636-644.

38. Lyxumia [product information]. Guildford, Surrey, UK: Sanofi; 2016.

39. Sanofi US. FDA accepts Sanofi new drug application for once-daily fixed-ratio combination of

insulin glargine and lixisenatide. http://www.news.sanofi.us/2016-02-22-FDA-Accepts-Sanofi-New-Drug-Application-for-Once-Daily-Fixed-Ratio-Combination-of-Insulin-Glargine-and-Lixisenatide. Updated February 22, 2016. Accessed May 20, 2016.

40. The diaTribe Foundation. Novo Nordisk's much-awaited basal insulin/GLP-1 analogue

combination Xultophy approved in Europe. http://diatribe.org/issues/69/new-now-next/4.

Updated September 22, 2014. Accessed May 20, 2016.

41. Reuters. U.S. panel backs approval of Sanofi combination diabetes drug.

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-sanofi-fr-fda-panel-idUSKCN0YG2VP. Updated May 25,

2016. Accessed June 17, 2016.

42. Reuters. RPT-UPDATE 2-U.S. FDA panel recommends approval of Novo Nordisk diabetes drug. http://www.reuters.com/article/novo-nordisk-fda-panel-idUSL2N18M064. Updated May 25,

2016. Accessed June 17, 2016.

Back to Top