Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Current Topics in Sterile Compounding: The Drug Quality and Security Act

INTRODUCTION

Compounding has been a role of traditional pharmacy practice for centuries. In fact, until the 1800s, large-scale drug manufacturers did not exist, so drug compounding was commonplace in the United States (U.S.). By the late 1800s, industrial manufacturing began to reduce the need for community-based compounding, but few laws governed drug manufacturing. In 1938, the U.S. Congress, in response to more than 100 human deaths due to an inappropriately formulated sulfanilamide elixir, enacted the Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act (FDCA). The FDCA most specifically addressed drug manufacturers and the dispensing of manufactured prescription drugs. In 2013, however, Congress enacted the Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA), which amended the FDCA to address prescription drug compounding specifically.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines compounding as, "...a practice in which a licensed pharmacist, a licensed physician, or, in the case of an outsourcing facility, a person under the supervision of a licensed pharmacist, combines, mixes or alters ingredients of a drug to create a medication tailored to the needs of an individual patient." 1 Preparation of a prescription drug for administration or dispensing according to FDA-approved manufacturer labeling instructions (e.g., simple reconstitution) is generally not considered compounding. (Note that USP definition defines preparation according to the manufacturer’s FDA approved labeling [simple reconstitution] as compounding and it is subject to the enforceable USP chapters such as 795, 797 and 800.)

The recent growth of pharmacy compounding has been influenced by multiple factors, including drug shortages; patient allergies that require specific excipients; new understandings of pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine; and removal of popular drug products from the market. Because pharmacists are compounding an increasing number of medications to meet patient-specific needs, they must be aware of the professional obligations and legal boundaries associated with this practice. To engage in compounding today, a pharmacist should be able to distinguish pharmacy compounding from drug product manufacturing and be capable of complying with strict standards under both federal and state law.

Recent legal changes were prompted, including the creation of the original FDCA, by a tragedy. In 2012, a number of patients died or became ill from fungal meningitis. Investigation revealed they were caused by contaminated compounded products prepared by New England Compounding Center (NECC). This focused attention on some pharmacies that were engaging in large-scale, non-patient-specific preparation of sterile products. Inspection for compliance with proper compounding practices–in particular, standards set forth by United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Compounding Compendium2 – was until that time almost exclusively the responsibility of state boards of pharmacy.

The NECC tragedy spurred a probe into whether state boards of pharmacy and FDA were adequately investigating and inspecting compounding pharmacies.3,4 A report prepared by then-Congressman (now-Senator) Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts concluded that some state boards of pharmacy were, for various reasons, supervising compounding pharmacies inadequately.5 The Markey report provided the impetus for several Congressional bills aimed at increasing FDA’s direct authority over compounding pharmacy practices and drawing a sharper line between permissible, traditional, patient-specific compounding and what amounted to prescription drug manufacturing under the guise of "compounding."

Ultimately, Congress passed the Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA), which President Barack Obama signed into law on November 27, 2013. The DQSA creates a new regulatory environment that defines the space between small-scale pharmacy compounding and drug manufacturing more concretely.6 The DQSA only applies to human drugs and not drugs for veterinary use; veterinary products are regulated under the Animal Medicinal Drug Use Clarification Act of 1994. Investigational drugs are also excluded from DQSA.6

THE DRUG QUALITY AND SECURITY ACT OF 2013

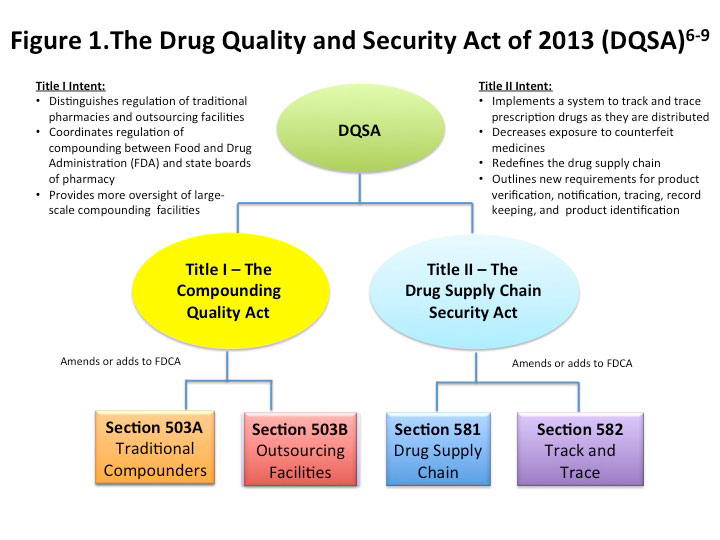

The DQSA is divided into 2 titles, illustrated by Figure 1.6,7

Title I is known as the Compounding Quality Act (CQA); it clarifies federal authority of compounding, defines "traditional compounders" under Section 503A of the FDCA, and creates Section 503B of the FDCA, which addresses outsourcing facilities. Title I also creates a Pharmacy Compounding Advisory Committee (PCAC), composed of 14 members (mostly pharmacists and physicians) and charged with providing "advice on scientific, technical, and medical issues concerning drug compounding under Sections 503A and 503B of the FDCA and, as required, any other product for which FDA has regulatory responsibility."8 PCAC also recommends drugs and substances to be included on "do not compound" and "approved bulk drug substances" lists.8,9,10,11

Title II of the DQSA, also known as the Drug Supply Chain Security Act amends the FCA to establish a track-and-trace system for monitoring the prescription drug supply chain, specifically to prevent introduction of counterfeit drugs into the U.S. supply.6 Title II of the DQSA will be implemented over a period of 10 years; its focus is beyond the scope of this article.

Section 503A: Traditional Compounders

DQSA Title I established 2compounding regulatory spaces. Section 503A sets forth requirements for traditional compounders; Section 503B creates and regulates outsourcing facilities.

In large part, Section 503A is not new; pharmacies have been subject to its provisions for years.12,13 The Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA) of 1997 created Section 503A to distinguish prescription drug manufacturing from compounding activities that could be performed by pharmacies. As enacted in 1997, Section 503A also prohibited pharmacies and physicians from soliciting for compounded prescriptions and barred advertising or promoting any particular compounded drug class or drug. Several pharmacies challenged these advertising restrictions as violating the free speech guarantees of the First Amendment. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed and struck down those restrictions in Thompson vs. Western States Medical Center.14

After Thompson, federal courts disagreed whether Section 503A had been struck in part or in whole. The Supreme Court did not address the advertising restrictions’ severability from the remainder of Section 503A. DQSA Title I resolved the debate by removing the unconstitutional advertising and promotion clauses from Section 503A and re-enacting the remainder of Section 503A.15

Section 503A defines when a pharmacy is engaged in traditional compounding rather than manufacturing. Any pharmacy engaged in traditional compounding must observe the requirements of Section 503A, and is exempt from 3 FDCA requirements that would otherwise apply to a prescription drug product:

- Compliance with current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) (Section 501(a)(2));

- Compliance with extensive manufacturer product labeling requirements, which are discussed below (Section 502(f)(1)); and

- Establishing the product is safe and effective for its intended use via new drug applications (NDAs) or abbreviated new drug applications (ANDAs) filed with FDA (Section 505).12,13

To qualify for exemptions from these requirements, a pharmacy must satisfy Section 503A’s numerous restrictions, which are detailed in the following paragraphs.

First, compounding must be performed by a licensed pharmacist in a licensed pharmacy or federal facility or by a licensed physician.13 This provision often raises questions for pharmacies that currently allow technicians under the direct supervision of the pharmacist to participate in compounding activities. Technically, pharmacists may still allow technicians to compound under their supervision. The explanation is found in interpretation of the FDCA; interpretations have traditionally considered the word "pharmacist" to mean a pharmacist or any member of the pharmacy staff working under a pharmacist's supervision in compliance with state law. State law is important in other ways, too. Several states require an additional or supplemental compounding license or sterile compounding license in addition to the traditional pharmacy license. Other states and jurisdictions are currently considering legislation for licensing of pharmacies that engage in compounding.

Second, compounding must be conducted in compliance with the standards outlined in USP Chapter <795> for nonsterile preparations and USP Chapter <797> for sterile preparations.13 The challenge with this provision is primarily in USP’s definition of compounding. FDA's definition of compounding is specific, such that these new rules only apply to pharmacies engaged in creating new products; but USP expands its definition of compounding to include any manipulation of bulk chemicals or a manufactured product, even if it is prepared according to the instructions appearing in the manufacturer’s approved labeling.16 The DQSA's intent is for pharmacists comply with USP standards. The discrepancies between FDA and USP definitions of compounding can be confusing and some sites have complained that state board and FDA interpretations differ, but technicians may still reconstitute injectable solutions and oral suspensions as allowed by state law.

Third, compounded products must be packaged in a manner to promote safety and stability as outlined in USP or other official compendium. Relatedly, compounded products must be labeled with appropriate instructions for safe and effective use by the patient, and the product’s labeling or advertising cannot contain false or misleading claims.13 These provisions differentiate traditional pharmacy compounded products from manufactured products in that the former only need to bear a pharmacy label with appropriate patient specific instructions, in addition to any information required by state law.

Note that Section 503A’s labeling requirements are narrower than those applicable to manufacturers. Manufacturer labeling includes not only to what is affixed to the container but also the package insert, patient package inserts (PPI), and medication guides. PCAC met in February and June of 2015 and expressed concern that the PPI is an important tool for increased patient compliance, especially with certain dosage forms (e.g., dry-powder inhalers). PCAC recommended that if compounders are not required to provide a PPI for dosage forms that are difficult to use or understand, then those dosage forms should not be compounded by a pharmacy.10

Fourth, a pharmacy may compound a prescription drug product only upon receipt of a valid prescription for an individual patient. A pharmacy may engage in the practice of anticipatory compounding for prescription drug products in limited quantities based on historical prescribing or a relationship between the compounder, the prescriber, and the patient. But, even then, the pharmacy may not dispense the product unless and until it receives a valid prescription for an individual patient.13

Section 503A does not specifically define limited quantities, which creates some uncertainty for compounding pharmacists. For example, dilutions of measurable quantities are required when drug products are compounded in extremely low concentrations (e.g., medications for children or neonates). Compounded preparations of this sort yield significantly more product than needed for a single prescription, and the pharmacist may want to store the remaining product for future prescriptions rather than waste it. Pharmacists should consider their regular orders carefully for compounded products when determining a quantity to prepare, including specifically USP standards.17 The pharmacist must also consider the length of storage of a compounded product to ensure that it is used before the beyond-use-date.

An additional and much-discussed concern is office use compounding. Many pharmacies compound drugs for local practitioners according to their state rules or statutes. Examples of office use products are numbing gels prepared for a dentist's office that have a quicker onset and shorter duration of action than commercially available products, and preservative-free intrathecal injections for pain clinics that treat patients who need analgesic doses that are significantly more concentrated than commercially available products. Pharmacists have provided a valuable service to patients and health care practitioners by compounding these and similar products for decades. In the past, pharmacies could work with local physicians' offices and prepare these products without a specific patient prescription. Under 503A, that is no longer possible. The International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists (IACP) contends that this is a burden, and the legislation supersedes states' rights of oversight.18

Fifth, all ingredients used for compounding must comply with USP or National Formulary (NF) monograph standards for strength, purity, and quality, or be a component of an FDA-approved human drug product. Any deviation from those standards must be noted on the compounded drug's label. Likewise, if a bulk drug substance is used, it must comply with the bulk drug substance standards in USP or NF monographs, or appear on an FDA list of bulk drug substances that are allowed without a USP or NF monograph. All bulk drug substances must be obtained from an FDA-regulated manufacturer and must be accompanied by valid certificates of analysis.13

These ingredient requirements concern compounding pharmacists. For instance, a significant number of drug products, herbal preparations, and nutraceuticals do not have established monographs. Also, these substances may not be readily available from established manufacturers with guaranteed and consistent potency or purity for compounding. Moreover, the "Approved Bulk Substances" list did not exist when the DQSA went into effect, and the development of such a list is ongoing (Table 1). The current list of bulk drug substances nominated for use in 503A compounding is maintained online at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/UCM467373.pdf.10

| In Mid 2016 Recommendations of the Pharmacy Compounding Advisory Committee |

| |

| Bulk drug substances allowed in compounding |

| Brilliant Blue G |

| Cantharidin |

| Diphenylcyclopropenone |

| N-acetyl-d-glucosamine |

| Iodide |

| Squaric acid dibutylester |

| Tranilast |

| Drugs that cannot be compounded with modifiers when included by the PCAC |

| Acetaminophen, except dosage units ≤325 mg |

| Adenosine phosphate, including adenosine monophosphate (AMP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) |

| Alatrofloxacin |

| Aminopyrine |

| Astemizole |

| Bisacodyl delayed-release tablets containing ≥ 10 mg bisacodyl per tablet |

| Bromfenac sodium, except ophthalmic solutions |

| Bromocriptine mesylate, except for lactation prevention |

| Cerivastatin sodium |

| Chloramphenicol |

| Cisapride |

| Esmolol hydrochloride parenteral products that supply 250 mg/mL concentrated esmolol per 10-mL ampule |

| Etretinate |

| Gatifloxacin, except for ophthalmic solutions |

| Grepafloxacin |

| Methoxyflurane |

| Novobiocin sodium |

| Ondansetron hydrochloride single-dose products > 16 mg for intravenous administration |

| Pemoline |

| Pergolide mesylate |

| Phenylpropanolamine |

| Propoxyphene |

| Rapacuronium bromide |

| Rofecoxib |

| Sibutramine hydrochloride |

| Tegaserod maleate |

| Troglitazone |

| Trovafloxacin mesylate |

| Valdecoxib |

| Any product containing polyethylene glycol 3350, sodium chloride, sodium bicarbonate, potassium chloride for oral solution |

| Source: References 8,9,10 |

Sixth, products that appear on the FDA list of drug substances having "Demonstrable Difficulties for Compounding" that could adversely affect the safety or efficacy of the compounded product cannot be compounded.13 As with the "Approved Bulk Substances" list, this category did not exist prior to passage of the DQSA. FDA has likewise asked the industry and the general public to suggest drugs that should be included on the "Demonstrably Difficult" list, and PCAC is reviewing those suggestions. The initial response to the call for suggestions was overwhelming. PCAC members have considered the possibility that many manufacturers, and even some outsourcing facilities, may have suggested products as a way to protect their own market share in the absence of patent protections.10 PCAC has also contemplated that a simple list of drug names may not be sufficient; the list may need to include modifiers related to the dosage form being compounded or the source of ingredients used in compounding that could affect the difficulty of compounding. These modifiers provide more robust guidance for both pharmacies and enforcement agencies, but adding the modifiers will also slow the creation of the list.

PCAC considers several factors in deciding whether specific drugs are acceptable to use in compounding, including the complexity of the formulation and compounding processes; drug delivery mechanism, dosage form, and physiochemical or analytical testing; the product's bioavailability and stability; the container closure and security; and the product's toxicity.10

To further complicate the PCAC’s deliberations on these newly created lists, sometimes the route of administration and not the drug product itself may play a role in drug safety. For example, some drugs currently being compounded have documented liver toxicities when administered systemically (i.e., orally or intravenously [IV]), but these toxicities do not occur with topical use. The same is true with regard to efficacy, which can vary with different indications. Pharmacies may not compound drugs withdrawn from the market for safety or efficacy (discussed below). It will be important, therefore, that FDA specify whether a drug product has been withdrawn entirely from the market for safety and efficacy reasons or whether only certain formulations have been withdrawn from the market. PCAC is charged with making recommendations for the list of drugs that cannot be compounded for safety/lack of efficacy concerns, and FDA intends to provide this list to compounding pharmacists once it is compiled; however, compiling the list has proven to be an ongoing and difficult process.8,9,10

Physicians and pharmacists who identify patients with a documented need for a drug on 1 of the not-be-compounded lists can file an Investigational New Drug (IND). They would prepare the application as a physician request for a single patient IND for compassionate or emergency use. Currently, these requests can be made to FDA by phone and providers usually receive a response within 24 hours. However, if practitioners begin to use this process for all the drugs not yet covered on the guidance lists, the process may deteriorate rapidly and become inefficient and unusable.10

Seventh, the DQSA restricts pharmacies’ ability to ship compounded drug products interstate. Unless the state in which the drug is compounded has entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with FDA, a pharmacy’s interstate distribution of compounded products cannot exceed more than 5% of the total prescription orders dispensed by the pharmacy or the compounding physician.18,19 FDA’s definition of distribution includes delivery or shipment to physicians’ offices, hospitals, or other health care settings "for administration and dispensing to an agent of the patient or a patient" with the intent to transport out of the state of origin.

For pharmacies located on or near state borders that have a significant patient population outside the state in which the pharmacy is registered, interstate shipment limitations (whether under DQSA’s "5% rule" or under the terms of an eventual MOU) could be problematic. And, this requirement could place a significant record-keeping burden on both pharmacies and state boards of pharmacy for tracking and auditing the number of compounded prescriptions that are destined to be taken out-of-state compared to the total prescription orders dispensed. State boards of pharmacy are understandably hesitant to enforce this requirement, because they are responsible for tracking and auditing; in addition, if the boards enter into the MOU, they will also be responsible for investigating, responding to, and addressing complaints related to compounded human drug products distributed outside the state. The proposed turn-around times in FDA's draft documents are quite short in many cases.19 This could create additional stress in state regulatory systems that are often already suffering from a shortage of resources.

Eighth, drugs that have been withdrawn from the market due to concerns about safety or a lack of efficacy may not be compounded.13 This requirement appears straightforward, but it is dependent on the correct information reaching FDA when a manufacturer removes a drug from the market for economic reasons. That information must also be communicated to pharmacists. When a manufacturer removes a drug that has not been involved in FDA recalls or warning letters, the documentation related to the reason for withdrawal can be difficult to obtain.20

Ninth, a pharmacy may not compound products that are essentially copies of commercially available drug products.13 This provision also seems straightforward until the ongoing drug shortage climate is considered. The number of drug shortages has declined steadily since its peak in 2011, largely because of legislation that strengthened FDA’s ability to respond to and resolve shortages. Yet, existing and new drug shortages are still problematic, especially for sterile products, because they seemingly last longer and are more difficult to resolve than previous shortages.21 These shortages result in many pharmacies receiving requests for drugs that are ordinarily commercially available, but are not available in a certain region or in a quantity sufficient to meet patient needs. In sterile compounding, this provision also raises a question about pharmacies that choose to compound the same dose in the same type and volume of IV fluid from a commercially available sterile drug vial and IV bag when frozen premixed IV preparations are available on the market.

Finally, FDA employs a risk-based enforcement approach, and does not provide information describing the process. FDA can inspect a compounding pharmacy, physician, or outsourcing facility without identifying a specific complaint or safety issue.13 From review of the inspections conducted to date, it appears that outsourcing facilities that compound high-risk sterile products are most likely to be inspected. With many unanswered questions related to the provisions of the DQSA, this method of enforcement is worrisome for pharmacies and physicians.

Several websites offer useful information, standards, and guidelines for pharmacy compounding. Standards for sterile and nonsterile compounding are available at USP website (www.usp.org).2 Current draft and final guidance documents for the DQSA/CQA are listed under "Regulatory Policy Information" at FDA website (www.fda.gov).22 FDA issued final guidance documents in June 2016. PCAC meeting minutes and applications and documentation related to the DQSA are also available on FDA website, and interested individuals can live-stream their meetings. Check these websites frequently for the latest drafts of pending legislation and guidance documents.

Section 503B: Outsourcing Facilities

In contrast to Section 503A, Section 503B is an entirely new section of the FDCA (see Table 2). Section 503B creates a new entry point for medications into the drug supply chain: the outsourcing facility. Outsourcing facilities can be used to fill the gap between traditional pharmacy compounding and industrial manufacturing where compounded products are needed for administration by health care facilities. The requirements that must be satisfied to qualify as a registered 503B facility, as well as implications of the provisions for both pharmacies considering obtaining 503B registration or contracting for services with a 503B facility, are discussed below. Registration and compliance with Section 503B exempts outsourcing facilities from the following FDCA requirements imposed on drug manufacturers:

- Compliance with extensive product labeling materials (Section 502(f)(1)), Section 503B does, however, impose other outsourcing facility-specific labeling requirements; they are discussed below)

- Proof of safety and efficacy of the drug product for its intended use through NDAs or ANDAs filed with FDA

- Compliance with track-and-trace requirements created by DQSA Title II

|

Table 2. Definitions and guidelines for pharmacies and outsourcing facilities under the 2 sections of the Drug Quality and Security Act |

| |

Section 503A – Defines traditional compounding pharmacies |

Section 503B – Defines outsourcing facilities |

| Who |

Applies to all pharmacies and compounding physicians |

Registration is voluntary and is open to pharmacies and non-pharmacies |

| A licensed practitioner must complete the compounding |

A pharmacist must supervise the compounding |

| What |

Applies to sterile and nonsterile preparations |

Applies to sterile compounding only (nonsterile compounding services can be provided, but only in addition to sterile compounding services) |

| Refers to USP definitions for mixing vs. compounding |

Does not refer to USP definitions |

| Compounded products that are allowed or prohibited are listed by FDA |

Compounded products that are allowed or prohibited are listed by FDA |

| Why |

Requires a prescription and an established physician-patient-pharmacist relationship |

No prescription is required |

| No "office use" of compounded products is allowed |

"Office use" of compounded products is allowed |

| How |

Mandates compliance with USP standards |

Mandates compliance with current good manufacturing practices |

| Only limited anticipatory compounding can be completed |

No limits are placed on the amounts that can be compounded, but distribution to a wholesaler is prohibited |

| Adequate labeling for use by patient must be provided |

Specific information is required on the label that notes the product has been compounded |

| Reporting of adverse events is voluntary |

Reporting of adverse events is mandatory |

| Only 5% of total products can be distributed out of state (unless the state has a MOU with FDA) |

No limits are placed on interstate commerce of compounded products |

| Regulated primarily by state boards of pharmacy, but also subject to direct regulation by FDA. |

Regulated primarily by FDA |

| Abbreviations: FDA, Food and Drug Administration; MOU, Memorandum of Understanding; USP, United States Pharmacopeia. |

Section 503B defines an outsourcing facility as "...a facility at 1 geographic location or address that—(i) is engaged in the compounding of sterile drugs; (ii) has elected to register as an outsourcing facility; and (iii) complies with all of the requirements of this section."23 Any pharmacy or compounding physician may, therefore, elect to register as an outsourcing facility, but outsourcing facilities are not required to maintain any additional registration, such as a pharmacy license, under federal law. (State law may require them to acquire a pharmacy license.)

A compounding entity may have multiple locations, but an individual registration is required for each location; there is no corporate registration option. Unlike pharmacies that compound under Section 503A, outsourcing facilities may compound drug products without receipt of a valid, individual patient prescription. Outsourcing facilities may also accept prescriptions for individual patients, but are not required to do so.

Also, an entity engaged in compounding that is not governed by Section 503A may elect not to register as a 503B outsourcing facility, since registration is voluntary. Although outsourcing registration is voluntary, compounding prescription drugs other than pursuant to individual patient prescriptions is only legal if the facility doing so is a 503B outsourcing facility. (Note that there is concern that while compounding without meeting the requirements of 503A or registering as a 503B is illegal, registration is voluntary. Nothing about this prevents "bad actors" from compounding without registering. FDA is aware of this problem and has stated that they hope market forces will prevent this problem since pharmacies, physicians and other HC entities will only do business with 503B registered facilities.) Regulators anticipate that pharmacies, hospitals, physicians’ practices, and outpatient care centers that currently need or prepare products that are not patient-specific will now obtain them from registered 503B facilities. This is an important consideration for organizations and facilities that purchase compounded products. Purchasers must note that upon initial registration and payment of all applicable fees, an outsourcing facility can be listed on FDA’s Registered Outsourcing Facilities list.24 This means that a facility can be listed before it is inspected.25

Section 503B(d)(5) defines a sterile drug as "…a drug that is intended for parenteral administration, an ophthalmic or oral inhalation drug in aqueous format, or a drug that is required to be sterile under Federal or State law."26 Compounding facilities must navigate the divide between this definition and the broader definition of "sterile drug" in USP. The safest choice would be to adhere to the broader definition, since the provision cites federal and state law and could include dosage forms such as irrigations and implants that are included in the USP definition. A compounding entity can be a qualified outsourcing facility if it compounds sterile products, but most of these facilities will likely also be involved in nonsterile compounding. Facilities engaged solely in nonsterile compounding do not qualify to register as an outsourcing facility.27

Outsourcing facilities must comply with cGMPs applicable to drug manufacturers. This is an important distinction between Sections 503A and 503B. Recall that under Section 503A, pharmacies compounding products pursuant to valid, patient-specific prescriptions and satisfying other conditions are exempt from cGMP compliance and instead subject to USP compliance.

Compounding at an outsourcing facility does not need to be performed by a licensed practitioner, but it must be performed under the direct supervision of a licensed pharmacist.

Compounded products from outsourcing facilities, while exempt from FDCA’s manufacturer labeling requirements, must nonetheless meet labeling requirements that go beyond those required of products from pharmacies in compliance with Section 503A. The labels of all products that are compounded by outsourcing facilities must include a statement that it is a compounded drug, and the lot or batch number of the drug, the established name of the drug, the dosage form and strength, the quantity or volume of drug, the date the drug was compounded, the expiration date, storage and handling instructions, the National Drug Code number (if available), the statement "Not for Resale," the statement "Office Use Only" (if applicable), and a list of active and inactive ingredients. The container of a compounded product must also include directions for use and instructions for reporting adverse events related to the compounded product.28

Outsourcing facilities may only use bulk drug substances for compounding if they are on FDA’s "Approved Bulk Drug Substances" list of ingredients allowed for compounding, or if the bulk drug substance is the subject of a USP/NF monograph. As is true under Section 503A for pharmacies, outsourcing facilities must acquire bulk drug compounding ingredients from an FDA-registered manufacturer and a valid certificate of analysis must accompany the drugs.23

Outsourcing facilities can compound copies of commercially available drugs that are in shortage at the time of compounding, but under Section 503A indicates pharmacies may not compound regularly or in inordinate amounts. To be considered shortage items, the drug must appear on FDA’s maintained list of shortage drugs. (Under 503A, pharmacies are prohibited from compounding products that are essentially copies of commercially available drug products and there is no provision for drugs that are "available" but in short supply.)23,27

Outsourcing facilities may not compound drugs that have been withdrawn from the market for safety or efficacy concerns, drugs that are essentially copies of approved drugs, and drugs that are demonstrably difficult to compound.27 "Demonstrably difficult" is ambiguous since, for a typical community pharmacy, this definition may not be the same as for a dedicated outsourcing facility, which could have a higher level of expertise and more suitable equipment. Still, only 1 "demonstrably difficult" list will be compiled by PCAC for all compounding facilities.

Outsourcing facilities may not sell or transfer compounded products to a wholesaler for redistribution. All products must be distributed within a health care setting (i.e., clinic, physician’s office, hospital) or dispensed directly to a patient or prescriber pursuant to a prescription. Outsourcing facilities cannot sell through wholesalers, but they can dispense to a practitioner for "office use." Again, a pharmacy compounding in compliance with Section 503A may not dispense compounded products except pursuant to a valid, patient specific prescription.23

An outsourcing facility must comply with any FDA-required Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) applicable to a product produced at the facility. Such reporting is voluntary for pharmacies that compound in compliance with Section 503A.23

Finally, an outsourcing facility must renew its registration with FDA annually. It must submit reports that list the drugs compounded by the facility twice a year. The outsourcing facility must also pay all applicable fees for registration—an annual establishment fee of $15,000 multiplied by an inflation adjustment factor, a small business adjustment factor, and reinspection fees.28 The annual registration period is October 1 through December 31 for the subsequent year. Failure to pay fees by December 31st of the year previous will result in loss of outsourcing facility status. Forms and information concerning outsourcing facility registration are available on FDA website.29

FDA inspects outsourcing facilities under a risk-based schedule, which includes consideration of the facility’s history, recall history, level of risk for drugs compounded, and if compounding from the drug shortage list. After a facility is inspected, FDA inspection reports (Form 483) are available on FDA’s website.27

By June 2015, 53 outsourcing facilities had registered with FDA.24 The current list of outsourcing facilities is maintained online; by late 2018, the number of facilities had surpassed 70.30

Additional Issues

The DQSA mandates improved communication among state boards of pharmacy and between the boards and FDA. Still, questions remain about enforcement. FDA is taking its role in preventing another tragedy very seriously and has started inspecting pharmacies under 503A. However, a review of the 483 inspection reports precipitates the question of whether or not FDA inspectors are prepared to change their focus from cGMP to USP standards.31 PCAC has also questioned whether FDA inspectors will transition from strictly punitive inspections to more formative assessments (similar to the Joint Commission) that allow organizations, both pharmacies and outsourcing facilities, an opportunity to correct identified problems.10

The types of inspections conducted by FDA have been controversial both in response to the NECC situation and in the implementation of the DQSA. Inspection reports, which use FDA's Form 483, are posted online for 503B outsourcing facilities along with recalls for all types of compounded products. Much can be learned by looking at the specific interpretations of applicable standards to the compounding performed by 503A and 503B facilities.32

Compounding pharmacies that previously produced compounded products for "office use" and the like (as opposed to patient-specific prescriptions) face a fundamental question: Should they abandon the practice or maintain it by registering with FDA as an outsourcing facility? Factors that will influence their decisions are the high initial registration and ongoing re-inspection fees and the substantial costs of creating and maintaining a cGMP-compliant facility. Smaller pharmacies that are involved in sterile compounding and hospital networks that would like to consolidate compounding will struggle with this decision. Facilities that have registered, however, can use registration as a point of differentiation. These facilities will have an advantage when partnering with hospitals and other facilities that purchase bulk compounded drugs.

CONCLUSION: THE FUTURE OF COMPOUNDING

The DQSA gives FDA more direct oversight of compounding practices. DQSA’s stringent requirements have, however, provoked substantial backlash among compounding pharmacy advocacy groups Bills have been introduced into Congress that seek to address these problems,33 and the IACP has been active in asking for legislative corrections to DQSA.34

Regardless of the status of legislation, pharmacy personnel must be vigilant for ongoing clarification, guidance documents, and new legislation in the area of compounding.

REFERENCES

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Compounding and the FDA: questions and answers. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/ucm339764.htm#what, July 12, 2016.

- United States Pharmacopeial Convention. USP-NF general chapters for compounding, http://www.usp.org/usp-healthcare-professionals/compounding/compounding-general-chapters, July 12, 2016.

- Multistate outbreak of fungal meningitis and other infections—case count. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/meningitis-map-large.html, July 12, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Justice. New England Compounding Center Pharmacist Sentenced for Role in Nationwide Fungal Meningitis Outbreak. Accessed at https://www.fda.gov/ICECI/CriminalInvestigations/ucm594800.htm, September 28, 2018.

- Markey EJ; U.S. House of Representatives. State of Disarray: How States' Inability to Oversee Compounding Pharmacies Puts Public Health at Risk. U.S. House of Representatives. 2013. Accessed at http://www.markey.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/State%20Of%20Disarray%20Compounding%20Report.pdf, July 12, 2016.

- The Drug Quality and Security Act, Pub L No. 113-54, 127 Stat 587.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Compounding: Compounding Quality Act, Title I of the Drug Quality and Security Act of 2013. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/default.htm, July 12, 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacy Compounding Advisory Committee. Final Rule: Accessed at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2014-01-13/pdf/2014-00322.pdf, July 16, 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacy compounding committee. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/PharmacyCompoundingAdvisoryCommittee/default.htm, July 16, 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Meeting materials, Pharmacy Compounding Advisory Committee: June 17-18, 2015. Accessed at https://www.archive-it.org/collections/7993 September 28, 2018.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacy compounding advisory committee roster. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/advisorycommittees/committeesmeetingmaterials/drugs/pharmacycompoundingadvisorycommittee/ucm381301.htm, July 12, 2016.

- Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC § 353a(a).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance: Pharmacy Compounding of Human Drug Products Under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act: Guidance. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug and Evaluation and Research; 2016. Accessed at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM469119.pdf, September 28, 2018.

- Thompson v Western States Medical Center, 535 U.S. 357, 357 (2002).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance Document, Pharmacy Compounding of Human Drug Products Under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (July 2014). Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 2014.

- United States Pharmacopeial Convention. United States Pharmacopeia 38/National Formulary 33. Rockville, MD: United States Pharmacopeial Convention; 2015. Accessed at http://www.usp.org/usp-healthcare-professionals/compounding/compounding-general-chapters, July 12, 2016.

- United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Compounding—sterile preparations. In: United States Pharmacopeia 38/National Formulary 33. Rockville, MD: United States Pharmacopeial Convention; 2015.

- International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists. IACP Files Comments for FDA's Prescription Requirement Under Section 503A Guidance. Accessed at http://www.iacprx.org/news/297954/IACP-Files-Comments-for-FDAs-Prescription-Requirement-Under-Section-503A-Guidance-.htm, July 12, 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft memorandum of understanding addressing certain distributions of compounded human drug products between the state of and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/UCM434233.pdf, July 12, 2016.

- National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. FDA extends comment period for compounding-related MOU. Accessed at https://www.nabp.net/news/fda-extends-comment-period-for-compounding-related-mou, July 12, 2016.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Shortage resources. Accessed at https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Shortage-Resources, September 28, 2018.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Regulatory policy information. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/ucm166743.htm, July 12, 2016.

- 21 USC §353b: Outsourcing Facilities. U.S. Code. Accessed at http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title21-section353b&num=0&edition=prelim, July 12, 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Registered outsourcing facilities. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/ucm378645.htm, June 25, 2015.

- 21 USC §353B(d)(4).

- 21 USC §353B(d)(5).

- 21 USC §353B(d)(10).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Fees for Human Drug Compounding Outsourcing Facilities Under Sections 503B and 744K of the FD&C Act. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2014. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm391102.pdf, July 12, 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Information concerning outsourcing facility registration. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/ucm389118.htm, July 12, 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Facilities registered as human drug compounding outsourcing facilities under section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act). Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/ucm378645.htm, September 28, 2018.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA's Human Drug Compounding Progress Report: Three Years After Enactment of the Drug Quality and Security Act. Accessed at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/UCM536549.pdf, September 28, 2018.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Compounding: Inspections, Recalls, and other Actions. Accessed at https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/ucm339771.htm, September 28, 2018.

- H.R.2871 – Preserving Patient Access to Compounded Medications Act of 2017. Accessed at https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/2871, September 28, 2018.

- 34. International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists. IACP Urges Congress to Protect Patient Access to Compounded Medications [news release]. Accessed at https://www.iacprx.org/news/384545/IACP-Urges-Congress-to-Protect-Patient-Access-to-Compounded-Medications.htm, September 28, 2018.

Back to Top