Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Hepatitis C Virus: Addressing the Burden of Disease in the Era of Antiviral Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacists have the opportunity to make a significant impact in the care of patients with HCV infection. With the availability of newer HCV direct–acting antiviral (DAA) medications, many patients are able to achieve a virologic “cure” following a relatively brief course of treatment.1,2 Despite this, the burden of disease remains high due to a number of barriers. These include patients who are unaware of their infection due to the asymptomatic nature of HCV, and patients who know they are infected but lack access to medical care or the social, emotional, and financial resources needed to follow through with successful treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND BURDEN OF DISEASE

According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), approximately 3.5 million Americans are currently infected with HCV.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 71 million people worldwide are living with HCV.4 WHO estimates the highest concentrations of HCV are in the eastern Mediterranean (2.3% of the population) and European areas (1.5% of the population). Outside of these two regions, approximately 0.5% to 1% of the population is affected.4

Disproportionate risk for HCV infection occurs among African Americans, U.S. veterans, and people who are coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).5 African Americans represent approximately 11% of the total U.S. population, but make up 25% of the population infected with HCV.6 Among HIV–infected individuals who use illegal injectable drugs, about 80% are coinfected with HCV.7 Among all users of injectable illicit drugs, roughly 30% to 70% have HCV.3 In addition, there is an emerging trend of HCV among Caucasians, possibly related to the current U.S. opioid epidemic. Injectable drug users are thought to be a major driver in the 294% increase in HCV incidence between 2010 and 2015.8

According to an NHANES study, 50% of people with HCV are undiagnosed and unaware of their condition.5 This is partly due to the fact that the infection can remain asymptomatic for decades.7 Patients may fail to seek treatment due to a lack of access to care, financial limitations, psychiatric or social comorbidities, inaccurate perceptions about the treatment course, and failure to be referred to a specialist. Access to health insurance influences HCV detection and outcomes. In the NHANES study, about 90% of the patients who were aware of their infection had health insurance compared with 60.4% who were unaware.5

Chronic HCV is responsible for approximately 10,000 deaths each year in the U.S.9 In 2007, HCV mortality rates actually surpassed those of HIV.6 Despite the availability of effective treatments, HCV–related deaths increased by 18% between 2010 and 2014.7 The presence of cirrhosis is a major determinant of mortality risk.6 Guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and Infectious Disease Society of America (AASLD/IDSA) recommend treatment for all persons infected with HCV except in cases of limited life expectancy.10

HCV DISEASE COURSE AND RELATED COMPLICATIONS

HCV is a blood–borne virus manifesting in both acute and chronic infection. The acute stage occurs after initial exposure and can last several weeks to months, during which patients may remain asymptomatic or have nonspecific symptoms. About 80% of persons with chronic HCV are asymptomatic in the early stages, but some may present with symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, anorexia, myalgia, arthralgia, and weakness.4,11 There is a 20% to 50% chance that the infection will resolve spontaneously and not progress to chronic HCV.12 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 65% of people with chronic HCV will eventually develop chronic liver disease. Between 5% and 20% will progress to cirrhosis within 25 years, and ultimately 1% to 5% will die from liver–related causes.7 Certain conditions predispose patients toward a higher risk for advanced liver disease, including:6,13–17

- HIV coinfection

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hepatitis B (HBV) coinfection

- High alcohol consumption

Progressive cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are the primary liver–related complications of HCV and are major contributors to all–cause mortality.18 HCV is the most common cause of liver transplantation.19

REDUCING HCV TRANSMISSION: VIRAL HEPATITIS ACTION PLAN

It is essential for pharmacy professionals to be aware of the factors that perpetuate HCV infection and enhance risk, and steps they can take to intervene. Goals and strategies identified by the CDC’s Viral Hepatitis Action Plan for 2017–2020 pertaining to HCV are outlined in Table 1.20

| Table 1. Summary of CDC’s Viral Hepatitis Action Plan for 2017–2020 |

| Goal 1 |

Prevent new viral hepatitis infections

(Decrease number of new HCV infections by at least 60%) |

| Strategies |

- Increase community awareness and decrease stigma and discrimination

- Support innovation by the health care workforce to prevent viral hepatitis

- Address critical data gaps and improve viral hepatitis surveillance

- Eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HBV and HCV

- Ensure that people who inject drugs have access to preventive services

- Reduce the transmission in health care settings

- Conduct research leading to new or improved viral hepatitis management approaches and optimal use of existing tools

|

| Goal 2 |

Reduce deaths and improve health of people living with viral hepatitis

(Increase the percent of persons aware of their HCV infection to 66%)

(Reduce the number of HCV-related deaths by 25%) |

| Strategies |

- Build capacity of health care workforce to diagnose viral hepatitis and provide care and treatment to persons living with infection

- Identify infected persons early in the course of disease

- Improve access to and quality of care and treatment

- Improve viral hepatitis treatment among persons living with HIV/AIDS

- Ensure that people who inject drugs have access to viral hepatitis care and evidence-based treatment services

- Expand access to and delivery of hepatitis prevention, care, and treatment services in correctional settings

- Monitor provision and impact of viral hepatitis care and treatment services

- Advance research to enhance identification, care, treatment, and cure for persons infected with viral hepatitis

|

| Goal 3 |

Reduce viral hepatitis health disparities

(Decrease number of new HCV infections among Native Americans/Alaska Natives and people aged 20–39 years by at least 60%)

(Reduce number of HCV-related deaths among people aged 55–74 years, Native Americans/Alaska Natives, and African Americans by at least 25%) |

| |

- Decrease health disparities by partnering with and educating priority populations and their communities about viral hepatitis and the benefits of available prevention, care, and treatment

- Improve access to care and the delivery of culturally competent and linguistically appropriate viral hepatitis prevention and care services

- Monitor viral hepatitis-associated health disparities in transmission, disease, and deaths

- Advance basic, clinical, translational, and implementation research to improve understanding of and response to viral hepatitis health disparities

|

| Goal 4 |

Coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities |

| Strategies |

- Increase coordination of viral hepatitis programs across federal government and among federal agencies, state, territorial, Tribal, and local governments as well as non-governmental stakeholders

- Strengthen timely availability and use of data

- Encourage development of improved mechanisms to monitor and report on progress toward achieving national viral hepatitis goals

- Regularly report on progress toward achieving the goals of the National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Viral Hepatitis Action Plan for 2017–2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hhs-actionplan.htm.20 |

HCV SCREENING AND TESTING PROCEDURES

There are numerous benefits for early screening and detection of HCV, especially given the improved effectiveness and tolerability of therapies. Treatment initiated prior to the development of cirrhosis and other complications is associated with higher cure rates and shorter, simpler courses of therapy.19 HCV screening is recommended for certain high–risk populations and persons who actively participate or have participated in certain high–risk behaviors (Table 2).7,10 HCV cannot be transmitted via hugging, sneezing, sharing eating utensils, or sharing food or water. Women who are of childbearing potential should be counseled on the risk of vertical transmission (about 6% in expectant mothers).7

| Table 2. HCV Screening Recommendations7,10 |

| "Baby boomers" born between 1945 and 1965 |

| Persons using injectable drugs |

| Persons using intranasal drugs |

| Receipt of hemodialysis or organ transplant and/or blood transfusions before the year 1992 |

| History of percutaneous or parenteral treatments (regulated or unregulated settings) |

| Children born to HCV-infected mothers |

| Persons previously incarcerated |

| Persons with HIV or beginning pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV |

| Organ donors |

| Presence of liver disease or unexplained elevated liver function tests |

Patients whose diagnosis is delayed have higher rates of hospitalization and mortality.21 “Late diagnosis” is defined as the presence of cirrhosis or decompensation within one year of initial diagnosis. In an observational study of 6,166 patients with HCV, 17% had a late diagnosis despite evidence that they had interacted with the healthcare system for an average of 6 years. These cases exemplify “missed opportunities” within the healthcare system to screen and diagnose HCV.21

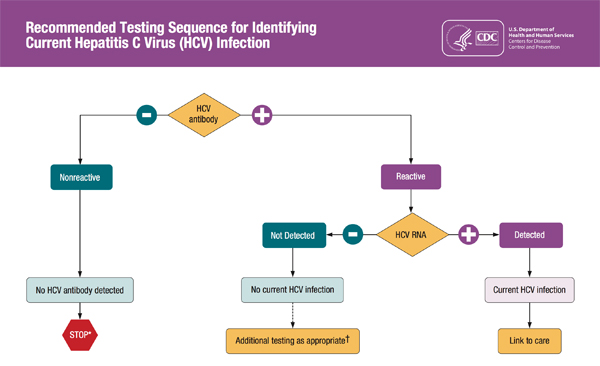

Testing for HCV initially includes a blood test for the HCV antibody. Because a positive HCV antibody does not distinguish between acute or chronic infection, an HCV RNA test must be obtained to confirm chronicity. If the HCV RNA test does not have a detectable viral load, this means that the acute infection has resolved on its own and no treatment is indicated.7,10 A testing algorithm recommended by the CDC is shown in Figure 1.22

Another step prior to initiating treatment is determining the HCV genotype.10 Although genotype 1 is the most common the U.S. comprising 74% of cases, six genotypes have been identified with up to 50 additional subtypes. The HCV genotype can direct the provider to the appropriate treatment regimen.7

In addition, all patients should be tested for evidence of current or prior hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection by measuring HBsAg and anti–HB. This is important before initiating treatment with DAA HCV therapies that may reactivate HBV.23

| Figure 1. CDC Testing Sequence for HCV Infection |

|

* For persons who might have been exposed to HCV within the past 6 months, testing for HCV RNA or follow–up testing for HCV antibody is recommended. For persons who are immunocompromised, testing for HCV RNA can be considered.

† To differentiate past, resolved HCV infection from biologic false positivity for HCV antibody, testing with another HCV antibody assay can be considered. Repeat HCV RNA testing if the person tested is suspected to have had HCV exposure within the past 6 months or has clinical evidence of HCV disease, or if there is concern regarding the handling or storage of the test specimen.

Source: Centers for Disease Control. CDC. Testing for HCV infection: An update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR. 2013;62(18). Available at: www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/pdfs/hcv_flow.pdf.22 |

Staging of the patient’s liver fibrosis is important for monitoring and treatment selection, and may include biopsy, liver elasticity testing, imaging, and use of blood biomarkers. The METAVIR liver scoring system (Table 3) has been commonly used to rank the severity of fibrosis, from no fibrosis (F0) to cirrhosis (F4).24 However, less–invasive methods for detecting severity of liver disease, such as indirect serum marker panels, are gaining an increased role in clinical practice.25

| TABLE 3. METAVIR Liver Scoring System24 |

| Scoring of Liver Fibrosis11 |

Condition of the liver due to HCV infection |

| F0 |

No fibrosis |

| F1 |

Portal fibrosis without septae |

| F2 |

Portal fibrosis with rare septae |

| F3 |

Portal central septae without cirrhosis |

| F4 |

Cirrhosis |

Decompensated cirrhosis is defined as presence of liver complications that may include ascites, esophageal and gastric variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy. In a study of 384 patients with cirrhosis, 3.9% transitioned to decompensated cirrhosis each year.26 Cirrhosis severity is calculated using the Child Turcotte Pugh (CTP) system based on laboratory values (total bilirubin, serum albumin, and prothrombin time or INR) and the degree of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. Class A denotes a lower severity of cirrhosis and Class C a high level of severity.10

Patients with cirrhosis are at increased risk for HCC, need for liver transplantation, and death.27 Once cirrhosis develops, the risk for HCC is approximately 3% per year.28 Extrahepatic manifestations may develop secondary to chronic HCV and may include diabetes mellitus, cryoglobulinemia, chronic kidney disease, skin manifestations, and malignancies unrelated to HCC (e.g., lymphomas). HCV has been associated with depression and reduced quality of life (QOL).29,30

CURRENT HCV TREATMENT APPROACHES

In addition to reducing the deleterious health effects and mortality risk of HCV, treating the infection has broader public health benefits by decreasing the risk of further transmission.10 Since the introduction of HCV DAAs treatment has become more tolerable and more effective in eradicating HCV.29

The goal of HCV treatment is to achieve a “virologic cure.” This is usually determined based on the sustained virologic response 12 weeks after the end of therapy (SVR12) when a patient’s HCV RNA levels are undetectable. The patient will continue to have HCV antibodies but have no HCV RNA unless re–infected.10 Available treatments have been shown to provide virologic cure for > 90% of patients who follow the medication regimen as prescribed.31

Patients with HCV should be treated as early in the course of disease as possible.10 Benefits of achieving a virologic cure of HCV include decreased liver inflammation, potential decrease of liver fibrosis, and a lower risk for HCC and need for liver transplant. Extrahepatic manifestations may also decrease in severity. Prior to treatment initiation it is important for the patient to have clear expectations and is assessed to ensure they are prepared for and committed to treatment. The treatment regimen must be tailored to HCV genotype, severity of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, prior treatment history for HCV, co–infections such as HIV as well as other preexisting conditions, and transplant history.10 Available HCV treatment options have expanded recently to include agents that can be used as monotherapy, for shorter courses, and for a broader range of HCV genotypes and other patient characteristics. These agents are able to target the various locations of viral replication.32 Table 4 describes the current DAA treatment options for HCV.33–44 Because guideline statements are updated regularly, it is advisable to consult the most recent statement, available at http://hcvguidelines.org.10 In general, Genotype 2 is considered easiest to treat. In comparison with other genotypes, genotype 3 is considered most challenging to treat; these patients may require combination treatment with ribavirin and/or longer treatment regimens.45

| Table 4. HCV Direct–Acting Antiviral Treatments33-44 |

| Brand Name |

Generic Name |

Dosage |

Common Adverse Effects* |

Potential Drug Interactions* |

| Mavyret |

glecaprevir 100mg

pibrentasvir 40mg |

Three tablets once daily for 8 to 12 weeks |

Headache, fatigue nausea |

Digoxin, dibigatran, carbamazepine, rifampin, ethinyl estradiol, St John's Wort, some HIV antiretroviral agents; HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, cyclosporine. Drugs that are substrates of P-gp, BCRP, OATP1B1 or OATP1B3 |

| Vosevi |

sofosbuvir 400 mg

velpastasvir 100 mg

voxilaprevir 100 mg |

One tablet once daily for 12 weeks |

Headache, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea |

Amiodarone

Acid-reducing agents such as H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump imhibitors

Reduced therapeutic effect when used in combination with P-gp or CYP inducers |

| Harvoni |

ledipasvir 90mg/

sofosbuvir 400mg |

One tablet once daily for 8 to 24 weeks |

Headache, weakness, fatigue, nausea, insomnia |

H2 Blockers

PPIs

Amiodarone

Rosuvastatin |

| Daklinza |

daclatasvir 60mg (use 30mg or 90mg if administering with CYP3A4 metabolized medications) |

One tablet once daily for 12 weeks in combination with sofosbuvir |

Headache, fatigue |

Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors/inducers Moderate CYP3A4 inducers |

| Sovaldi |

sofosbuvir 400mg |

One tablet once daily for 12 to 24 weeks |

When used with ribavirin: fatigue, headache.

When used with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin: fatigue, headache, nausea, insomnia and anemia |

Amiodarone P-gp inducers |

| Viekira Pak XR |

paritaprevir 150mg/ ritonavir 100mg/ ombitasvir 25mg/ dasabuvir 250mg |

Three tablets once daily for 12-24 weeks |

Nausea, pruritus, insomnia

When used with ribavirin: fatigue, nausea, pruritus, skin reactions, insomnia, asthenia |

|

| Olysio |

simeprevir 150mg |

One tablet once daily for 12 to 24 weeks with sofosbuvir or peginterferon and ribavirin |

Fatigue, headache, nausea, photosensitivity |

Statins Strong/Moderate CYP3A4 inducers Strong/Moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors |

| Zepatier |

elbasvir 150mg/ grazoprevir 100mg |

One tablet once daily for 12 to 16 weeks |

Fatigue, headache, nausea

When used with ribavirin: Headache, anemia |

OATP1B1/3 inhibitors Strong/Moderate CYP3A4 inducers Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors Statins |

| Epclusa |

velpatasvir 100mg/ sofosbuvir 400mg |

One tablet once daily for 12 weeks |

Headache, fatigue

When used with ribavirin in decompensated cirrhosis: fatigue, anemia, diarrhea, nausea, headache, insomnia |

Moderate P-gp inducers Strong/Moderate CYP 2D6, 2C8, 3A4 inducers H2 Blockers PPIs Antacids Amiodarone |

| Technivie |

paritaprevir 150mg/ ritonavir 100mg/ ombitasvir 25mg |

Two tablets once daily for 12 weeks |

When used with ribavirin: weakness, fatigue, nausea, insomnia |

Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors P-glycoprotein, BCRP, OATP1B1 or OATP1B3 inhibitors

Digoxin, amiodarone, HIV antivirals, pravastatin, alprazolam, omeprazole, hydrocodone, buprenorphine, quetiapine |

| Copegus, Rebetrol |

ribavirin 200mg |

Weight based dosing |

See above |

Didanosine, azathioprine |

*Partial listing; not all–inclusive.

BCRP=breast cancer resistance protein; CBC=complete blood count; INR=international normalized ratio; LFT=liver function tests; NS5A=nonstructural protein 5A; P–gp=P–glycoprotein; PPI=proton pump inhibitors |

There is currently no vaccine for the treatment or prevention of HCV but there is active research to develop one at this time.4 Monitoring steps for patients while on therapy include screening for Hepatitis B, complete blood count (CBC), INR, liver function tests (LFTs), and renal function prior to initiation, and CBC, rental function, and LFTs after four weeks of treatment and as needed.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS WITH HCV

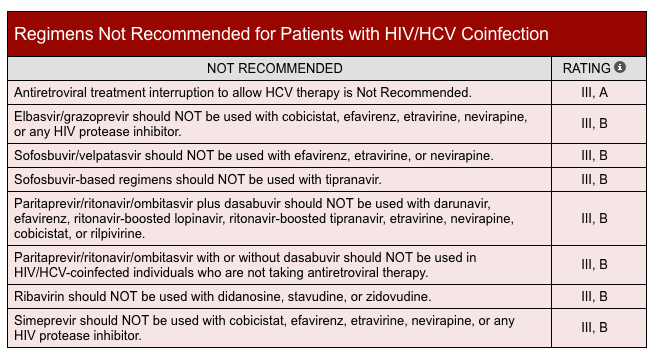

Specialized management of HCV is required for patients with prior liver transplant, renal impairment, HIV coinfection, decompensated cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. This information is detailed in the AASLD/IDSA HCV guidelines and in specific guideline documents.13,46 Coinfection with HIV adds considerably to the overall complexity of HCV treatment. The risks for cirrhosis and other complications are significantly increased in patients with concomitant HIV. For patients with HIV coinfection, screening for potential drug–drug interactions with the patient’s HIV antiretroviral regimen is essential prior to selecting an HCV DAA regimen. Of particular concern is the potential for HCV drugs to lower the bioavailability of some antiretroviral agents, particularly the “boosted” protease inhibitor combinations containing tenofovir.47,48 Alternative combination regimens are available, but it is necessary for the pharmacist to carefully assess the risks for drug–drug interactions and determine which combinations are contraindicated for coinfected patients. A list of combinations to be avoided per AASLD/IDSA recommendations is found in Table 5.46

| Table 5. Drugs Combinations to Avoid in Patients With HIV–HCV Coinfection46 |

|

Newer HCV antiviral regimens are associated with higher cure rates due to lower risk of adverse reactions, simpler regimens with fewer drugs and doses, and shorter durations of therapy (as low as 8 to 12 weeks for some patients).49,50 However, between 1% and 15% of patients will not reach SVR12 following treatment with an HCV DAA. The AASLD/IDSA guideline discusses recommendations for retreatment based on the patient’s treatment history. NS5A resistance–associated substitutions (RASs) can lead to treatment failure and there are clear guidelines for retreatment.51 Patients who do not achieve SVR12 should continue to be monitored for complications such as cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis.10

For patients who have serologic evidence of prior HBV infection, pharmacists should counsel patients about the risk of HBV reactivation when taking an HCV DAA if they are not on suppressive therapy.23 HBV reactivation is characterized as an abrupt increase in HBV replication manifesting as a rapid increase in serum HBV DNA level. Patients with serologic evidence of HBV infection should be monitored for clinical and laboratory signs of hepatitis flare or HBV reactivation during HCV treatment and during the post–treatment follow–up period. HBV suppressive therapy should be added if appropriate.23

PHARMACOECONOMIC OF TREATING HCV

The cost of the HCV DAA regimens are significant, but this must be considered relative to the costs of managing patients with severe liver failure and the societal costs associated with continued spread of the disease.52 A pharmacoeconomic study of treatment–naive patients with genotype 1 HCV demonstrated a cost savings following treatment ranging from less than $0 to $31,452 per quality–adjusted life year (QALY) gained, varying according to the level of liver fibrosis.53 QALY was shown to increase in patients with cirrhosis who had previously failed interferon–based regimens. Pharmacy benefit managers and government programs can play a role in negotiating reimbursement discounts to decrease overall costs. Governing bodies should continue to work together to increase access to these life–saving medications.10

ROLE OF THE PHARMACIST IN HCV MANAGEMENT, COUNSELING, AND FOLLOW–UP

As key members of the multidisciplinary team, pharmacists can have a significant impact on the outcomes of patients with HCV prior, during and after treatment.54–57 Because these therapeutic regimens can be highly complex, outcomes can be improved by the pharmacist’s expertise in optimizing therapy.54 This includes selecting an appropriate regimen, screening and monitoring for drug–drug interactions and adverse effects, and providing extensive patient counseling and monitoring during and after treatment initiation. Pharmacists are able to discuss transmission risks, screen and counsel patients for drug interactions including OTC medications and supplements, monitor for dietary interactions, and review for HCV resistance. The pharmacist can recommend dosage adjustments or alternatives if needed.57

For patients with chronic HCV, it is important to provide counseling on ways to reduce further progression of liver damage. Because drinking alcohol can accelerate HCV–related fibrosis, complete abstinence is recommended—but many patients will require further support and assistance to achieve this goal. Likewise, avoidance of illicit drugs should be encouraged to prevent further damage to the liver.7 Regular marijuana use has been correlated with rapid liver fibrosis progression possibly via the stimulation of hepatic cannabinoid receptors, so patients should also be encouraged to abstain from marijuana use.58 Moderate coffee consumption is usually acceptable in patients with for. Coffee has been associated with slower rates of liver fibrosis progression, with a possible effect of decreased decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma rates.59 Pharmacists can also advise patients with HCV about the importance of a healthy and balanced diet, and avoiding fatty foods. This can go a long way toward protecting patients from obesity and diabetes, reducing liver inflammation, and slowing progression to cirrhosis. Interestingly, grapefruit has been found to be potentially beneficial in patients with HCV.60 Patients with cirrhosis should receive screening for HCC.61 Pneumococcal vaccination is recommended, along with vaccination against hepatitis A and B, which should be initiated routinely upon diagnosis of HCV.10,62

Pharmacist counseling is very important for patients whose treatment regimen includes ribavirin. Ribavirin can cause birth defects if used during pregnancy or within 6 months following treatment in both men and women. Pharmacists should counsel patients about ribavirin use, urge patients to use two forms of birth control while on treatment, and complete pretreatment and monthly pregnancy tests within this time frame.40 A full review of medications and concurrent disease states by the pharmacist can help to minimize the risk of accelerated fibrosis.7 Table 6 includes some common drug–disease interactions occurring in association with HCV. For example, to prevent further acceleration of hepatotoxicity, it is recommended that patients limit their acetaminophen intake to a maximum of 2 grams daily.56

| Table 6. Drug–Disease interactions*63,64 |

| Medication |

Altered response to due to advanced liver disease |

Management techniques |

| Quetiapine, haloperidol |

Metabolized in the liver, can cause drug accumulation |

Use in caution and limit doses |

| Antidepressants (including most SSRIs) |

Metabolized in the liver, can cause drug accumulation |

Limit dosages and begin at low doses |

| Beta-blockers |

May cause hepatotoxicity based on the agent chosen |

Start at a low dose and increase as needed for optimal clinical response |

| HIV antiretrovirals |

Review each medication closely to monitor for interactions |

Review each medication closely to monitor for interactions |

| Herbal supplements |

Unknown toxicity due to known and unknown ingredients |

Monitor closely for liver related toxicity and limit use |

| Calcium channel blockers |

Bioavailability is prolonged |

Start at a low dose and increase as needed for optimal clinical response |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) |

Decreases creatinine clearance, increased bioavailability, hepatotoxicity |

Avoid or limit intake |

| Acetaminophen |

Increased half-life and reduced glutathione stores to decrease toxic metabolite |

Recommend a maximum daily dose of 2 grams per day and do not combine with other medications containing acetaminophen |

| Opioid analgesics |

May accumulate |

Monitor and tailor the regimen based on the status of the patient's fibrosis |

| *Partial listing |

Pharmacists should also take care to review for drug–drug interactions that can reduce effectiveness of therapy. For example, for medication regimens including ledipasvir (combination ledipasvir/sofosbuvir tablet), the concurrent use of acid–reducing agents such as omeprazole or pantoprazole can decrease ledipasvir concentrations, potentially resulting in sfailure of HCV therapy. If omeprazole must be used, the pharmacist should recommend the lowest possible dose, given with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir on an empty stomach, to minimize the drug interaction.33

Pharmacist intervention is especially important to ensure adherence to the HCV regimen. Pharmacists should help patients to identify and overcome specific obstacles to adherence. At each follow–up visit, it is important to emphasize to patients why optimizing adherence provides the best chance for a cure. A Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center study of 372 patients with HCV showed that addition of pharmacists to the management team resulted in a SVR12 rate of 94.1%.54 The medication possession ratio (MPR) calculates the patient’s adherence based on the pharmacy claims data. An MPR of 98.7% indicated nearly perfect adherence within this study population. These interventions resulted in lower medication costs relative to cure rates.54

Following treatment, patients should be advised that they will always have a positive HCV antibody, but they are considered cured if they achieved SVR12 (undetectable HCV RNA). Despite a cure or SVR12, people with a history of HCV are ineligible to donate blood.10 It is important for the patient to understand that although their HCV infection may be considered cured, there may be existing liver damage. Patients with advanced liver disease require frequent monitoring for complications of cirrhosis. These patients should be referred to a hepatologist and/or liver transplant center.10 Pharmacists can aid the providers in the monitoring of liver disease progression to help address a shortage of available providers with this expertise.38

Conclusion

HCV can be treated and cured more easily with the availability of the new DAA HCV agents. These agents are more effective, can treat a wider range of HCV genotypes, and have simpler administration schedules with a shorter in duration of therapy than then previously available medications. The medications are very expensive; however, they are still cost efficient to decrease the overall effects of HCV such as cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, and the possible need for transplantation. A number of barriers must be overcome in the treatment of HCV. As part of the multidisciplinary team, pharmacists can directly aid in easing some of these burdens. Through their participation in screening, counseling, medication selection, and monitoring, pharmacists can have a significant impact in optimizing the care of patients with HCV.

REFERENCES

- Rosenthal ES, Graham CS. Price and affordability of direct-acting antiviral regimens for hepatitis C virus in the United States. Infect Agent Cancer. 2016;11:24.

- Yau AH, Yoshida EM. Hepatitis C drugs: the end of the pegylated interferon era and the emergence of all-oral interferon-free antiviral regimens: a concise review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. Sep 2014;28(8):445-451.

- Edlin BR, Eckhardt BJ, Shu MA, Holmberg SD, Swan T. Toward a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. Nov 2015;62(5):1353-1363.

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis C fact sheet. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/ Accessed July 2017.

- Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. Mar 04 2014;160(5):293-300.

- Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. Feb 21 2012;156(4):271-278.

- Division of Viral Hepatitis and National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. HIV and Viral Hepatitis. CDC website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/factsheets/hiv-viral-hepatitis.pdf Updated June 2017.

- CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance—United States, 2015. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2017. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2015surveillance/index.htm

- NIDA. National Institute On Drug Abuse. The Science of Drug Abuse and Addiction. Facts About Drug Abuse and Hepatitis C. 2000. Available at: https://archives.drugabuse.gov/NIDA_Notes/NNVol15N1/Tearoff.html.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Available at: http://hcvguidelines.org/full-report-view.

- Merican I, Sherlock S, McIntyre N, Dusheiko GM. Clinical, biochemical and histological features in 102 patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Q J Med. Feb 1993;86(2):119-125.

- Kamal SM. Acute hepatitis C: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(5):1283-1297.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents: considerations for antiretroviral use in patients with coinfections. Hepatisis C (HCV)/HIV coinfection. Updated April 8, 2015.

- Negro F. Facts and fictions of HCV and comorbidities: steatosis, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases. J Hepatol. Nov 2014;61(1 Suppl):S69-78.

- Gish RG. HBV/HCV Coinfection and Possible Reactivation of HBV Following DAA Use. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). May 2017;13(5):292-295.

- Clark PJ, Thompson AJ, Zhu Q, et al. The association of genetic variants with hepatic steatosis in patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis Sci. Aug 2012;57(8):2213-2221.

- Martin MT, Deming P. Closing the Gap: The Challenges of Treating Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 3 Infection. Pharmacotherapy. Jun 2017;37(6):735-747.

- Khullar V, Firpi RJ. Hepatitis C cirrhosis: New perspectives for diagnosis and treatment. World J Hepatol. Jul 18 2015;7(14):1843-1855.

- Simmons B, Saleem J, Heath K, Cooke GS, Hill A. Long-Term Treatment Outcomes of Patients Infected With Hepatitis C Virus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Survival Benefit of Achieving a Sustained Virological Response. Clin Infect Dis. Sep 01 2015;61(5):730-740.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Viral Hepatitis Action Plan for 2017–2020. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hhs-actionplan.htm.

- Moorman AC, Xing J, Ko S, et al. Late diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infection in the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS): Missed opportunities for intervention. Hepatology. May 2015;61(5):1479-1484.

- CDC. Testing for HCV infection: An update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR 2013;62(18).

- Yeh ML, Huang CF, Hsieh MH, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B in patients of chronic hepatitis C with hepatitis B virus infection treated with direct acting antivirals. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. Feb 23 2017.

- Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. Aug 1996;24(2):289-293.

- Papastergiou V, Tsochatzis E, Burroughs AK. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2012;25(3):218-231.

- Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, et al. Morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type C: a retrospective follow-up study of 384 patients. Gastroenterology. Feb 1997;112(2):463-472.

- Conde I, Vinaixa C, Berenguer M. Hepatitis C-related cirrhosis. Current status. Med Clin (Barc). Jan 20 2017;148(2):78-85.

- Hu KQ, Tong MJ. The long-term outcomes of patients with compensated hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis and history of parenteral exposure in the United States. Hepatology. Apr 1999;29(4):1311-1316.

- Spiegel BM, Younossi ZM, Hays RD, Revicki D, Robbins S, Kanwal F. Impact of hepatitis C on health related quality of life: a systematic review and quantitative assessment. Hepatology. Apr 2005;41(4):790-800.

- Rodger AJ, Jolley D, Thompson SC, Lanigan A, Crofts N. The impact of diagnosis of hepatitis C virus on quality of life. Hepatology. Nov 1999;30(5):1299-1301.

- Yehia BR, Schranz AJ, Umscheid CA, Lo Re V, 3rd. The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101554.

- Schaefer EA, Chung RT. Anti-hepatitis C virus drugs in development. Gastroenterology. May 2012;142(6):1340-1350 e1341.

- Harvoni [package insert]. Forest City, CA: Gilead Sciences; 2017.

- Daklinza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2017.

- Sovaldi [package insert]. Forest City, CA: Gilead Sciences; 2017.

- Viekira XR [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc.; 2017.

- Olysio [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2017.

- Zepatier [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

- Epclusa [package insert]. Forest City, CA: Gilead Sciences; 2017.

- Copegus [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: GenentechUSA, Inc.; 2011.

- Technivie [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc.; 2017.

- Pegintron [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2016.

- Vosevi [package insert]. Forest City, CA: Gilead Sciences; 2017.

- Mayvret [package insert]. North Chicago, IL; AbbVie; 2017.

- Johnson SW, Thompson DK, Raccor B. Hepatitis C Virus-Genotype 3: Update on Current and Emergent Therapeutic Interventions. Curr Infect Dis Rep. Jun 2017;19(6):22.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Unique patient populations: patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Available at: http://www.hcvguidelines.org/unique-populations/hiv-hcv. Updated 4/12/2017.

- El-Sherif O, Khoo S, Solas C. Key drug-drug interactions with direct-acting antiviral in HIV-HCV coinfection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. Sep 2015;10(5):348-354.

- Milazzo L, Cattaneo D, Calvi E, et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions between telaprevir and antiretroviral drugs in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients with advanced liver fibrosis and prior HCV non-responders. Int J Antimicrob Agents. May 2015;45(5):545-549.

- D'Ambrosio R, Degasperi E, Colombo M, Aghemo A. Direct-acting antivirals: the endgame for hepatitis C? Curr Opin Virol. Jun 2017;24:31-37.

- El Sherif O, Afhdal N, Curry M. No one size fits all - shortening duration of therapy with direct acting antivirals for Hepatitis C genotype 1 infection. J Viral Hepat. Jun 05 2017.

- Aghemo A, Buti M. Hepatitis C Therapy: Game Over! Gastroenterology. Nov 2016;151(5):795-798.

- Neff GW, Duncan CW, Schiff ER. The current economic burden of cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). Oct 2011;7(10):661-671.

- Chhatwal J, Kanwal F, Roberts MS, Dunn MA. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of hepatitis C virus treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in the United States. Annals of internal medicine. Mar 17 2015;162(6):397-406.

- Yang S, Britt RB, Hashem MG, Brown JN. Outcomes of Pharmacy-Led Hepatitis C Direct-Acting Antiviral Utilization Management at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. Mar 2017;23(3):364-369.

- Martin MT, Faber DM. Patient satisfaction with the clinical pharmacist and prescribers during hepatitis C virus management. J Clin Pharm Ther. Dec 2016;41(6):645-649.

- Mohammad RA, Bulloch MN, Chan J, et al. Provision of clinical pharmacist services for individuals with chronic hepatitis C viral infection: Joint Opinion of the GI/Liver/Nutrition and Infectious Diseases Practice and Research Networks of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. Dec 2014;34(12):1341-1354.

- Spooner LM. The expanding role of the pharmacist in the management of hepatitis C infection. J Manag Care Pharm. Nov 2011;17(9):709-712.

- Ishida JH, Peters MG, Jin C, et al. Influence of cannabis use on severity of hepatitis C disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Jan 2008;6(1):69-75.

- Setiawan VW, Wilkens LR, Lu SC, Hernandez BY, Le Marchand L, Henderson BE. Association of coffee intake with reduced incidence of liver cancer and death from chronic liver disease in the US multiethnic cohort. Gastroenterology. Jan 2015;148(1):118-125; quiz e115.

- Nahmias Y, Goldwasser J, Casali M, et al. Apolipoprotein B-dependent hepatitis C virus secretion is inhibited by the grapefruit flavonoid naringenin. Hepatology. May 2008;47(5):1437-1445.

- Dmitrewski J, El-Gazzaz G, McMaster P. Hepatocellular cancer: resection or transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5(1):18-23.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Liver disease and adult vaccination. Reviewed May 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/health-conditions/liver-disease.html.

- Lewis JH, Stine JG. Review article: prescribing medications in patients with cirrhosis - a practical guide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Jun 2013;37(12):1132-1156.

- Chandok N, Watt KD. Pain management in the cirrhotic patient: the clinical challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. May 2010;85(5):451-458.

Back to Top