Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

2017 Update: Module 6. The Importance of Chronic Disease Management in MTM

Chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability in the United States. People are living longer with chronic diseases, which often means that they require complex medical treatment over a period of many years. People with chronic diseases tend to take multiple medications, have overlapping medical conditions, and have an increasing risk of disease–

related complications and medication side effects as they age. Improving the management of chronic diseases is the major focus of medication therapy management (MTM). Pharmacy technicians work regularly with patients who have chronic diseases. In most practice settings, people with chronic diseases are the main population receiving MTM services. One reason why improving care for these patients is so important is that many chronic diseases—

and their complications—are mostly or partly preventable. Improved management of chronic diseases can help reduce hospitalizations, disability, missed time from work and family responsibilities, and overall healthcare costs.

Impact of Chronic Disease in the U.S.

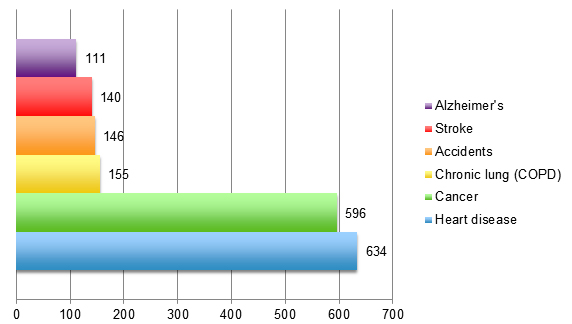

Chronic diseases are a growing concern worldwide—even in parts of the world facing issues such as infectious diseases, malnutrition, and maternal/child mortality.1 In the U.S., chronic diseases are the major health threat. Half of all adults—about 117 million people—have at least one chronic health condition, while about 25% of adults have two or more chronic health conditions.2 Seven of the top 10 causes of death are chronic diseases, including heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. The top two chronic diseases (heart disease and cancer) make up nearly half of all deaths (Figure 1).3

| Figure 1. Leading Causes of Death, United States, 2015 (Thousands; 000)3 |

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health United States 2016 [2015 data], Table 19. |

Chronic diseases are a common cause of death, but also carry a burden of illness and disability for individuals living with these conditions. Some diseases that may not be significant causes of death—such as arthritis—are associated with high levels of disability.4 Patients with chronic conditions like heart disease are surviving longer, as shown in the chart in Figure 2.1 Longer survival times from chronic disease, combined with increasing risk factors, means that the number of people affected (the prevalence) increases each year.

Figure 2. Worldwide Decline in Heart Disease Deaths

Men aged ≥ 30 (1950 to 2002)1 |

|

| Source: World Health Organization. Preventing Chronic Diseases: A Vital Investment. WHO Global Report. 2005.1 |

How Lifestyle and Behavioral Factors Affect Chronic Disease

The technical definition of “chronic disease” is a disease that lasts three months or longer.5 Other definitions describe chronic disease as a condition that is considered long–term or permanent (incurable) and one that cannot be prevented by vaccines or cured by medications.)6 Many chronic diseases are partly or even mostly preventable. The diagram below from a World Health Organization (WHO) report on chronic disease shows how modifiable (e.g., unhealthy diet, too little exercise) and non–modifiable (e.g., age, heredity) risk factors lead to common chronic diseases (Figure 3).1

| Figure 3. Impact of Risk Factors on Chronic Diseases1 |

|

| Source: World Health Organization. Preventing Chronic Diseases: A Vital Investment. WHO Global Report. 2005.1 |

The four key modifiable risk factors associated with most of the disability and death due to chronic disease are:

- 1) Unhealthy diet

- 2) Lack of exercise

- 3) Smoking or other tobacco use

- 4) Excessive alcohol use

According to the CDC:3

- Less than half of adults (age 18 and over) meet daily recommendations for physical activity

- Less than one–fourth of adults meet recommendations for muscle–strengthening activity

- A significant proportion of adolescents and adults say they eat fruit and/or vegetables less than once per day

- One in 5 adults reported being current smokers (2011 data)

- Cigarettes cause 480,000 deaths annually, which amounts to approximately 1 in 5 deaths each year (2014 data)

- Of the 88,000 deaths attributed to alcohol use each year, more than half are due to binge drinking among people who are not alcohol dependent.

Following the diagram in Figure 3 to the right, we see that unhealthy lifestyle choices lead to intermediate risk factors such as high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high cholesterol levels, and excess weight or obesity. These risk factors are treatable, and intervention combined with steps toward improving lifestyle can prevent and even reverse the effects of chronic diseases. However, these problems are complex and are rarely “easy fixes.” Obesity is an underlying factor in many chronic diseases in this country, with rates of obesity among adults and children rapidly climbing. The maps in Figure 4 show that both obesity (left) and diabetes (right) are widespread in the U.S., particularly in the Southeastern states.7 Obesity is a major risk factor for heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and kidney disease—as well as joint injuries, stress–related illness, fertility problems, and many other health conditions.

| Figure 4. Obesity and Diabetes Across America7 |

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. |

Chronic Diseases and Medicare Part D Coverage of MTM

Pharmacy technicians who participate in MTM will need to understand the Core Chronic Disease States that qualify for coverage of MTM services under Medicare Part D.

Medicare Part D “sponsors” are private insurance/managed care companies that provide drug benefits to people enrolled in Medicare Part D.8 To try to lower drug costs and better manage disease, Medicare will reimburse these organizations for the cost of MTM services. Some sponsors offer their own MTM services (often via telephone). Or they may contract with pharmacies to provide MTM services. Patients who receive MTM services under Medicare Part D must meet certain criteria, as outlined below.

For automatic enrollment (eligibility) in MTM, patient must meet all 3 criteria:9

1. Two or more chronic diseases

(Some sponsors may be more lenient and extend MTM services for patients with one chronic disease.)

The sponsor may elect to cover MTM for any set of chronic diseases, but they must include at least 5 of the 9 “core” chronic conditions listed below:

CMS suggested “core” chronic conditions include:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Chronic heart failure

- Diabetes

- Dyslipidemia

- End–stage renal disease

- Hypertension

- Respiratory disease (e.g., asthma, COPD, other chronic lung disorders)

- Bone disease (e.g., osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis)

- Mental illnesses (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, other chronic disabling disorders)

2. Use of multiple drugs (covered by Medicare Part D)

Each Medicare Part D sponsor determines the specific drugs covered under its formulary. The number of prescription drugs the patient must be taking to quality for MTM usually ranges between 2 and 8. (Sponsors cannot require that patients be taking more than 8 drugs to qualify for MTM services.)9

3. High annual medication costs

For the year 2016 the amount set by CMS is $3,507 or higher. The sponsors look at first–

quarter drug spending to estimate the likelihood of a patient spending this amount over a year. (This amount is adjusted by CMS each year.) Some prescription drug plans have set a higher threshold for the annual drug costs in order for the patient to qualify for MTM.

How Can MTM Help in the Management of Chronic Diseases?

There are many examples of research showing that pharmacist–provided MTM services can have positive, tangible effects on the management of chronic diseases. Diabetes is one of the most prominent disease states in which research has been done. Studies have shown that, compared with usual care, patients receiving MTM (or similar services) are more likely to reach treatment goals for diabetes such as target hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels and to have higher medication adherence rates.

- A study conducted at Vanderbilt University (2015) showed that medically underserved patients with uncontrolled diabetes who received pharmacist–provided MTM services had higher rates of medication adherence, lower A1C levels, and lower LDL cholesterol levels.10

- A Minnesota study compared the long–term effects of pharmacist–led MTM services with standard care in patients with diabetes. The percentage of diabetes patients who were optimally managed was significantly higher in the group receiving MTM. MTM patients were more likely to meet the HbA1c criteria and had greater overall reductions in HbA1c.11

A study of the effects of MTM in multiple disease states was conducted in Connecticut, in which 9 pharmacists worked closely with 88 Medicaid patients between July 2009 and May 2010 to conduct MTM services. Over this time period:12

- 369 patient–pharmacist encounters were analyzed

- 917 drug therapy problems were identified by pharmacists

- 78% of problems were resolved without referring patient back to primary care provider

- 82% of prescribers made changes in therapy based on pharmacists’ recommendations

Table 1 summarizes benefits of pharmacist–provided MTM services on health outcomes for patients with chronic diseases such as heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

| Table 1. Benefits of MTM in Selected Health Outcomes |

| Disease state/condition |

# patients (# studies)

Source |

Outcome/effect of pharmacist intervention |

| Diabetes |

2,247 (16)13 |

Significantly reduced HbA1c levels |

Diabetes

(10-City Challenge) |

573 (1 multicenter)14 |

Influenza vaccination rate doubled; eye and foot examination rates increased |

Diabetes

(Asheville Project) |

12 community pharmacies followed for 5 years15,16 |

Significantly reduced mean HbA1c; increased % of patients with optimal A1c; improved lipid levels; decreased costs of care; decreased sick days |

| Hypertension |

2,246 (13)17 |

Significantly reduced systolic blood pressure |

| Multiple chronic conditions |

Connecticut Medicaid Project12 |

917 drug therapy problems identified in 369 pharmacist/patient encounters; pharmacists resolved 78% without additional physician visit |

MTM for Children with Chronic Diseases

Chronic diseases are not just among older adults. Increasingly, children are living with chronic diseases, especially conditions associated with environmental causes (such as asthma) and lifestyle (such as diabetes). There are many circumstances in which MTM can be beneficial for parents of children with chronic disease. An example might be a child who has frequent emergency room visits and/or excessive use of rescue medications for asthma.18 MTM counseling can help the parent (or adolescent) to better understand the purpose of asthma maintenance therapies.19 Other examples would be children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, or HIV/AIDS, which require complex regimens utilizing high–cost specialty drugs.20,21

Childhood obesity is a growing public health concern. Currently one in 3 children are overweight. About 17% of all U.S. children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years are obese, with higher rates among Hispanics (22%) and blacks (20%).22 Type 2 diabetes used to occur only rarely in children, but now represents almost half of all childhood diabetes diagnoses.23 Diabetes among overweight and obese children is a particular problem among black and Hispanic populations.24 Studies show that children with diabetes have poor medication adherence and poor glucose control, and that diabetes tends to progress faster in younger patients.23 Thus pharmacist–provided MTM targeted at parents and teens/adolescents with diabetes may help establish lifestyle changes and patterns to help them manage this complex condition.

Conclusion

An understanding of chronic diseases and the magnitude of the problem is especially important in the practice of MTM. Pharmacy technicians may interact frequently with these patients and should have an appreciation of the potential for MTM to aid in chronic disease management.

References

- World Health Organization. Preventing Chronic Diseases: A Vital Investment. WHO Global Report. 2005.

- Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11:E62.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Updated March 17, 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading–causes–of–

death.htm.

- Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Theis KA, et al. Prevalence of doctor–diagnosed arthritis and arthritis–

attributable activity limitation—United States, 2010–2012. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(14):869–873. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6244a1.htm.

- Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, et al. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Preventing chronic disease. 2013;10:E66.

- Center for Managing Chronic Disease. Putting People at the Center of Solutions. University of Michigan, 2011.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Division of Diabetes Translation. April 2017. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/slides/maps_diabetesobesity_trends.pdf.

- Office of the Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare Part D Sponsors. OEI–02–07–00460, Oct 2007.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2016 Medication Therapy Management (MTM) Programs: Summary of 2016 MTM Programs. May 4, 2016.Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/CY2016-MTM-Fact-Sheet.pdf

- Skinner JS, Poe B, Hopper R, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of pharmacist–directed medication therapy management in improving diabetes outcomes in patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(4):459–465.

- Brummel AR, Soliman AM, Carlson AM, et al. Optimal diabetes care outcomes following face–to–face medication therapy management services. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(1):28–34.

- Smith M, Giuliano MR, Starkowski MP. In Connecticut: improving patient medication management in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):646–654.

- Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, et al. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part I: systematic review and meta–analysis in diabetes management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(10):1569–1582.

- Fera T, Bluml BM, Ellis WM. Diabetes Ten City Challenge: final economic and clinical results. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(3):383–391.

- Cranor CW, Bunting BA, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: long–term clinical and economic outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):173–184.

- Cranor CW, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: factors associated with outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):160–172.

- Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, et al. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part II: Systematic review and meta–analysis in hypertension management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(11):1770–1781.

- Al–Muhsen S, Horanieh N, Dulgom S, et al. Poor asthma education and medication compliance are associated with increased emergency department visits by asthmatic children. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10(2):123–131.

- Frey SM, Fagnano M, Halterman JS. Caregiver education to promote appropriate use of preventive asthma medications: what is happening in primary care? J Asthma. 2015:1–7.

- Kibicho J, Owczarzak J. A patient–centered pharmacy services model of HIV patient care in community pharmacy settings: a theoretical and empirical framework. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(1):20–28.

- Len CA, Miotto e Silva VB, Terreri MT. Importance of adherence in the outcome of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16(4):410.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood Obesity Facts. Updated June 19, 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html.

- D'Adamo E, Caprio S. Type 2 diabetes in youth: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 Suppl 2:S161–165.

- Lawrence JM, Mayer–Davis EJ, Reynolds K, et al. Diabetes in Hispanic American youth: prevalence, incidence, demographics, and clinical characteristics: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32 Suppl 2:S123–132.

Back to Top